To identify the neurological diseases for which euthanasia and assisted suicide are most frequently requested in the countries where these medical procedures are legal and the specific characteristics of euthanasia in some of these diseases, and to show the evolution of euthanasia figures.

MethodsWe conducted a systematic literature review.

ResultsDementia, motor neuron disease, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease are the neurological diseases that most frequently motivate requests for euthanasia or assisted suicide. Requests related to dementia constitute the largest group, are growing, and raise additional ethical and legal issues due to these patients’ diminished decision-making capacity. In some countries, the ratios of euthanasia requests to all cases of multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease, or Huntington disease are higher than for any other disease.

ConclusionsAfter cancer, neurological diseases are the most frequent reason for requesting euthanasia or assisted suicide.

Identificar las enfermedades neurológicas por las que con mayor frecuencia se solicita la eutanasia y el suicidio asistido en los países donde están legalizados, las particularidades de la eutanasia en algunas de ellas y mostrar la evolución de sus cifras.

MétodosRevisión bibliográfica sistemática.

ResultadosLas demencias, enfermedad de motoneurona, esclerosis múltiple y enfermedad de Parkinson son las enfermedades neurológicas que más frecuentemente motivan la petición de eutanasia o suicidio asistido. Las solicitudes por demencia son las más numerosas, están creciendo y plantean problemas éticos y legales adicionales al disminuir la capacidad de decisión. En algunos países la proporción de solicitudes respecto al total de casos de esclerosis múltiple, enfermedad de motoneurona o enfermedad de Huntington es mayor que en cualquier otra enfermedad.

ConclusionesDespués del cáncer las enfermedades neurológicas son el motivo más frecuente de pedir la eutanasia y el suicidio asistido.

Physician-assisted dying, whether euthanasia or assisted suicide (EAS), is a controversial subject whose acceptance varies between countries,1,2 members of the public, and healthcare professionals, who are generally less amenable to the idea than the general public.3,4 Euthanasia and assisted suicide were made legal in the Netherlands in 2002, and subsequently in Belgium, Luxembourg, Colombia, and Canada, under different circumstances in each country.5 Assisted suicide (but not euthanasia) is legal in Switzerland, in some states in Australia, and in the American states of Oregon, Washington, and more recently Vermont, California, Colorado, Hawaii, and New Jersey. This review is exclusively descriptive and is intended to provide information to help each healthcare professional to make their own assessment. EAS was legalised in Spain in March 2021,6 and neurologists will receive queries from patients due to the incurability, intolerable suffering, and loss of quality of life associated with some neurological diseases. To prevent our patients reaching this point, we should intensify palliative care in diseases that cause patients to request EAS, and seek to rule out or treat depression, which is 4 times more frequent among patients with terminal cancer and requesting euthanasia than among those who do not make this request.7 This review addresses the following questions: which neurological diseases most frequently lead patients to request EAS? Since their authorisation, have euthanasia and assisted suicide become more or less frequent? What specific circumstances must we take into account in certain neurological diseases?

MethodsTo address these questions, a systematic review was conducted of the literature from January 2002, the year that EAS was first legalised, in the Netherlands, to December 2020. The literature search included studies on humans and published in English, French, and Spanish. Articles were gathered from the MEDLINE/PubMed, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE databases, with the following search strategy: (Euthanasia [Title/Abstract] OR Suicide, Assisted [Title/Abstract]) AND (Neurologic diseases OR Dementia OR cognitive impairment OR stroke OR motor neuron disease OR ALS OR Multiple sclerosis [MeSH Terms]) AND («2002»[Date - Completion]: «3000»[Date - Completion]). The search yielded a total of 1409 publications from MEDLINE/PubMed, 60 from Cochrane Library, and 201 from EMBASE. Of these, 940 were selected and 65 included for review.

Results and discussionIn the countries in which EAS is legal, these procedures account for 0.3% to 4.6% of all deaths.1 The most frequent age interval (accounting for approximately half of cases of EAS for all reasons) is 60 to 85 years; slightly over half of patients are men, except in Switzerland and since 2018 in Belgium.5 In countries in which both euthanasia and assisted suicide are legal (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg), euthanasia accounted for the majority of assisted deaths. The tables below present the different diseases most frequently leading to requests for EAS in the different countries in which they are legal. These data are not fully comparable between countries as different classification criteria are used.

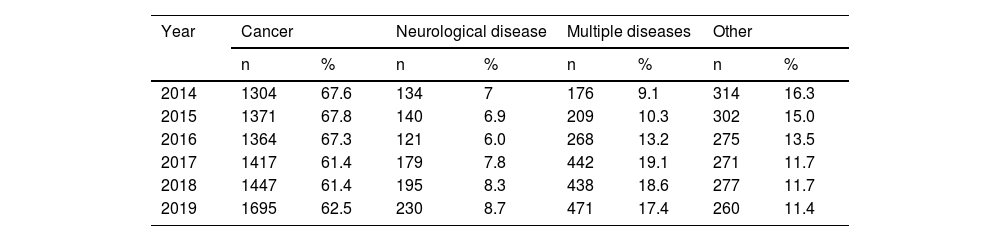

Diseases leading to requests for euthanasia in different countriesBelgiumTable 1 shows the slight growth observed in recent years in the total number of EAS and in the proportion attributed to multiple diseases.8–10 In Belgium, like in the other countries, neurological diseases are the second leading single cause of EAS, after cancer. Dementia (1% of all assisted deaths in 2019) is classified separately; including dementia, neurological causes of EAS account for nearly 10% of the total.

Diseases associated with assisted dying in Belgium.

| Year | Cancer | Neurological disease | Multiple diseases | Other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 2014 | 1304 | 67.6 | 134 | 7 | 176 | 9.1 | 314 | 16.3 |

| 2015 | 1371 | 67.8 | 140 | 6.9 | 209 | 10.3 | 302 | 15.0 |

| 2016 | 1364 | 67.3 | 121 | 6.0 | 268 | 13.2 | 275 | 13.5 |

| 2017 | 1417 | 61.4 | 179 | 7.8 | 442 | 19.1 | 271 | 11.7 |

| 2018 | 1447 | 61.4 | 195 | 8.3 | 438 | 18.6 | 277 | 11.7 |

| 2019 | 1695 | 62.5 | 230 | 8.7 | 471 | 17.4 | 260 | 11.4 |

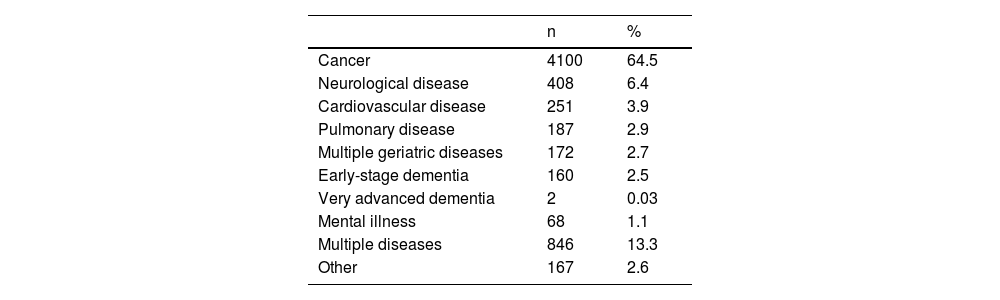

Once more, neurological diseases are the second leading single cause of EAS in the Netherlands, after cancer; including dementia, they account for a similar proportion as in Belgium (9%) (Table 2).11 Cases of cognitive impairment without dementia should also be added, as they are categorised under geriatric syndromes. The most frequent neurological cause was dementia (in early stages in the vast majority of cases), followed by Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and motor neuron disease/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Less frequent causes were stroke,12 Huntington disease, and other degenerative diseases of the central nervous system.

Diseases associated with assisted dying in the Netherlands in 2019.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 4100 | 64.5 |

| Neurological disease | 408 | 6.4 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 251 | 3.9 |

| Pulmonary disease | 187 | 2.9 |

| Multiple geriatric diseases | 172 | 2.7 |

| Early-stage dementia | 160 | 2.5 |

| Very advanced dementia | 2 | 0.03 |

| Mental illness | 68 | 1.1 |

| Multiple diseases | 846 | 13.3 |

| Other | 167 | 2.6 |

In the Netherlands in 2019, a total of 6092 cases of euthanasia (95.8% of the total), 245 of assisted suicide (3.9%), and 24 combined cases (0.4%) were recorded. Physician-assisted dying accounted for 4.2% of all deaths. If we apply the same percentage to the total number of deaths in Spain, the total would amount to 17 586 cases of EAS for the same year. In the Netherlands in 2015, the medical care received immediately before death was for the control of pain and symptoms in 36% of cases, other treatments in 17%, palliative sedation in 18%, and EAS in 4.6%.13 Not all requests are granted: in a survey of 3614 general physicians from the Netherlands,14 44% of requests resulted in EAS; in the remaining cases, the patient died before EAS was performed (13%) or before the decision was made (13%), or the request was withdrawn (13%), or refused (12%). In Belgium, 77% of requests result in EAS.

In Luxembourg in the period 2009 to 2015, the causes of euthanasia and assisted suicide (only one case of the latter) were terminal cancer in 43 cases, neurodegenerative diseases in 7, and one case each of neurovascular and other systemic disease.15 No data are available on the neurological diseases leading patients to request euthanasia in Colombia.

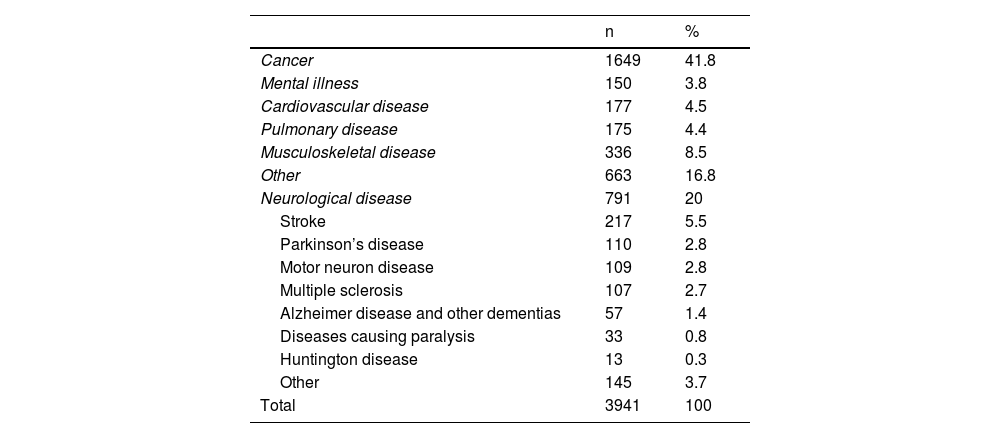

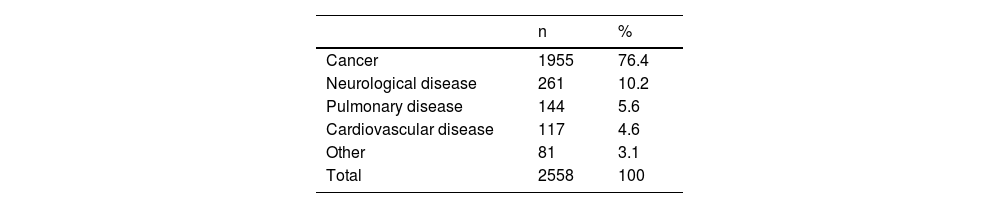

SwitzerlandIn Switzerland, assisted suicide is legal, but not euthanasia. As in the countries discussed above, incidence of assisted dying is growing: 2666 cases were recorded in 2009 to 2014, compared to 1275 in the period 2003 to 2008. In absolute terms, neurological disease is the second leading cause of assisted suicide, after cancer (Table 3). However, the percentage of assisted suicides among all deaths for a given disease was highest in patients with neurological disease, particularly those under 65 years old, in whom the highest percentages were observed for multiple sclerosis, Huntington disease, and motor neuron disease (11.1%, 9.9%, and 6.5%, respectively).

Diseases associated with assisted dying in Switzerland in 2003-2014.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 1649 | 41.8 |

| Mental illness | 150 | 3.8 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 177 | 4.5 |

| Pulmonary disease | 175 | 4.4 |

| Musculoskeletal disease | 336 | 8.5 |

| Other | 663 | 16.8 |

| Neurological disease | 791 | 20 |

| Stroke | 217 | 5.5 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 110 | 2.8 |

| Motor neuron disease | 109 | 2.8 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 107 | 2.7 |

| Alzheimer disease and other dementias | 57 | 1.4 |

| Diseases causing paralysis | 33 | 0.8 |

| Huntington disease | 13 | 0.3 |

| Other | 145 | 3.7 |

| Total | 3941 | 100 |

In Switzerland, assisted suicide is provided by 2 private, non-medical organisations, in addition to the public healthcare system; these organisations also offer their services to citizens of countries where assisted suicide is not yet authorised (between 1998 and 2020, one organisation assisted 1460 individuals from Germany, 475 from the United Kingdom, and 37 from Spain, among a total of 3025 patients).17,18 After cancer (38% of all requests), such neurological diseases as motor neuron disease and multiple sclerosis also constituted the second leading motive for requesting EAS at these organisations (24.5% of the total).19

Oregon and Washington (USA)Some states in the USA (Oregon, Washington, and more recently Montana, Vermont, California, Hawaii, Colorado, and New Jersey) have legalised assisted suicide but not euthanasia (which has recently been legalised in Canada). Unlike in European countries, only patients with terminal disease are able to request assisted suicide. In these states, neurological diseases once more constitute the second leading cause of assisted suicide, after cancer (Table 4).20,21 No data are available for analysis from Vermont, Colorado, California, Montana, or New Jersey because of how recently assisted suicide was legalised in these states.

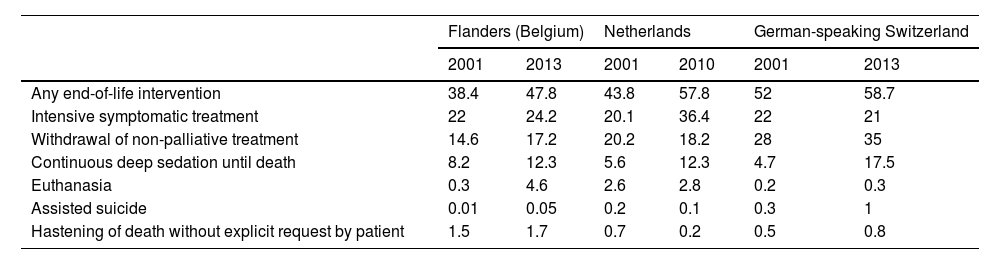

Progression of end-of-life interventionsTable 5 shows the end-of-life interventions that general practitioners reported applying in their patients, and the trend in the use of these interventions over 10 to 13 years in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.22–24 In all 3 countries, a specific intervention is applied in around half of patients attended at the end of life, with intensive symptomatic treatment and withdrawal of non-palliative treatment being the most common; generally, both of these approaches have become more frequent, as was also the case for palliative sedation, the third most frequent measure. Though euthanasia and assisted suicide were less frequent, their incidence also increased. Assisted suicide is relatively rare, except in Switzerland, where euthanasia is not legal.

Progression of end-of-life interventions (%).

| Flanders (Belgium) | Netherlands | German-speaking Switzerland | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2013 | 2001 | 2010 | 2001 | 2013 | |

| Any end-of-life intervention | 38.4 | 47.8 | 43.8 | 57.8 | 52 | 58.7 |

| Intensive symptomatic treatment | 22 | 24.2 | 20.1 | 36.4 | 22 | 21 |

| Withdrawal of non-palliative treatment | 14.6 | 17.2 | 20.2 | 18.2 | 28 | 35 |

| Continuous deep sedation until death | 8.2 | 12.3 | 5.6 | 12.3 | 4.7 | 17.5 |

| Euthanasia | 0.3 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Assisted suicide | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 |

| Hastening of death without explicit request by patient | 1.5 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

Rates of assisted suicide are lower in Oregon and Washington than in European countries, although, since its legalisation in 2017, rates have trebled, reaching over 3 cases per 1000 deaths. Unlike in the Netherlands, where 80% of assisted deaths occur at the patient’s home,11 87% of these patients in Oregon and 64% in Washington die at a palliative care hospital. In Switzerland, the rate of assisted suicides has trebled over a decade, with a greater increase in the population aged over 65 years; no changes were observed over time in patients’ sex, level of education, or economic situation.16 The reason for the increase in rates of EAS since its legalisation is unclear. It has been suggested that legalisation may have “normalised” the taboo of deciding to end one’s own life. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that, whereas violent and unassisted suicides decreased in Europe as a whole between 2001 and 2019 (from 21.3 to 12.8/100 000 population), they have increased in the Netherlands (from 9.6 to 11.8).25

Specific considerations on euthanasia and assisted suicide in the context of dementiaBetween 2010 and 2018, the total number of requests for EAS due to any disease in the Netherlands doubled (from 3136 to 6126), whereas requests by patients with dementia increased nearly six-fold (from 25 to 146). Alzheimer’s disease is the most frequent dementia motivating these requests, followed by vascular dementia, mixed dementia, unspecified dementia, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and Huntington disease.26 Seven percent of patients with Huntington disease died through euthanasia in the period 2007 to 2010.27 In these patients, fear of going through the same experience as affected family members and of being admitted to a nursing home are the main reasons for requesting EAS.28 Unlike patients with Huntington disease or motor neuron disease, patients with dementia and without depression do not present increased suicide risk.29 Rather, the main reason cited by these patients with mild dementia for requesting EAS is a negative outlook regarding the future progression of their disease,30 although they are only able to make the request so long as they are legally competent; in order to request that euthanasia be performed after they are no longer competent, they must use advance directives to request that this take place when they reach a pre-specified point of advanced disease. Thus, the ethical and legal dilemmas at play in any case of euthanasia are further complicated by the question of determining whether this specified point has been reached, and who should decide this.31,32 It is also difficult to establish whether the patient’s suffering is unbearable, as is demanded by Dutch legislation, both because it is not possible to ask the patient and because the slow progression of the disease may lead to habituation.33 We are also unable to ask patients whether they have changed their mind, as occurs in 8.6% to 12% of patients with mild dementia and no advance directive.14,26 These difficulties also extend to patients with intellectual disability or autism spectrum disorder.34 As a result, the majority of physicians, both in the Netherlands35–37 and in Belgium,38,39 refuse to perform euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia who requested this in advance directives. In 2017 and 2018, fewer than 2% of cases of euthanasia due to dementia in the Netherlands were due to advanced disease.40 In the Netherlands, the only instance of a physician being prosecuted for performing euthanasia was a case in which the procedure was performed in a patient who had signed an advance euthanasia directive while she was still competent.41 Cognitive problems that may interfere in decision-making are the reason for which assisted suicide is not authorised in patients with Alzheimer disease (with or without an advance directive), Parkinson’s disease, or mental illness, or in minors in North America (Oregon, Canada),42 in contrast with the situation in Belgium and the Netherlands. The general public, and our patients and their caregivers, are more supportive of performing euthanasia in patients with dementia (even advanced dementia) than are physicians,43 whose acceptance of euthanasia ranges from 10% to 33% in different countries.44,45 The burden of caring for a patient with dementia provokes suicidal and even homicidal ideation among caregivers.46 For general practitioners and geriatricians in the Netherlands, euthanasia in patients with dementia is associated with a significant moral and emotional burden.47

Specific considerations on euthanasia and assisted suicide in the context of motor neuron diseaseIt is also essential to evaluate the cognitive status and decision-making ability of patients with motor neuron disease, which is associated with frontotemporal dementia in 10% of cases.48,49 It is important to record the patient’s desire for limitation of life-sustaining treatment, where applicable, as it is particularly upsetting to disconnect the ventilator of a patient whose life depends on this equipment.50 In a survey of patients with motor neuron disease in the USA, 60% believed that assisted suicide should be legalised, but only 7% would request it if it were legal51; another survey reported percentages of 44% and 1%, respectively, for the same questions.52 Requesting assisted suicide is associated with hopelessness and pessimism about the future but not with depression, which, surprisingly, does not usually worsen with the course of this disease.17,21 In terminal phases, pain, discomfort, insomnia, despair, and the feeling of being a burden for caregivers are predictive of requests for assisted suicide in Oregon.53 The proportion of patients requesting assisted dying is higher among patients with motor neuron disease than among those with cancer in both Oregon and the Netherlands, where one in 5 patients die assisted deaths.54–56 In Sweden, the risk of suicide was 6 times higher among patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, particularly in early stages of the disease, than in the general population.57 In contrast, 94% of patients with motor neuron disease in Switzerland do not intend to hasten their death.58 An additional problem in fully paralysed patients in the USA, where assisted suicide but not euthanasia is legal, is patients’ motor difficulties interfering with administration of the lethal substance.59

Specific considerations on euthanasia and assisted suicide in the context of multiple sclerosis, stroke, and Parkinson’s diseaseLittle specific information on EAS in these diseases has been published. For example, strokes causing dementia are classified under dementias in some countries. In Switzerland, 5.5% of all assisted suicides are associated with stroke,16 2.8% with Parkinson’s disease, and 2.7% with multiple sclerosis (Table 3). Suicidal ideation is more frequent in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration than in the context of Parkinson’s disease.60 Between 1984 and 1993, a total of 41 cases of EAS (2.4% of all cases) due to stroke and 14 due to multiple sclerosis (1% of the total) were recorded in the Dutch province of North Holland. Ninety-three percent of patients with stroke were older than 60 years, whereas 77% of those with multiple sclerosis were younger than 60.61 Multiple sclerosis is associated with increased suicide risk.62 Suicidal ideation is more likely when the disease affects leisure activities or when it is associated with depression or a sensation of social exclusion, and less likely when patients have a sense of purpose in life, feel productive, or have spiritual beliefs.63 As in motor neuron disease, stroke associated with severe motor deficits limits patients’ ability to carry out assisted suicide.64

This review may present a selection bias with respect to the data on EAS reported in different countries: while it is not mandatory to report assisted suicides in Switzerland, this is obligatory in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg, although EAS may be under-reported on death certificates.65 Its strength is that it shows the current outlook of EAS due to neurological disease worldwide; this situation is frequent, complex, and topical, but is very little studied.

ConclusionsIn the countries in which EAS is legal:

- -

The second leading cause of EAS is neurological disease, with dementia being the most common of these.

- -

Dementia is associated with additional ethical and legal dilemmas.

- -

Euthanasia and assisted suicide have become more frequent in countries in which they have been authorised.

- -

Euthanasia is requested approximately 10 times more than assisted suicide in countries in which both are legal.

This study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

Conflicts of interestNone.