Chagas’ disease is caused by the protozoa Trypanosoma cruzi, in which kidney injury is rarely described. The aim of this study is to describe the features of kidney injury in Chagas’ disease.

MethodsThis is a review study regarding kidney injury associated with Chagas disease. A deep search was performed in the main medical databases (PubMed and Scielo), using the key words “Chagas disease” and “Kidney”.

ResultsRenal involvement is a rare manifestation of Chagas’ disease, and there are few studies on the subject in literature. There is evidence of functional and structural renal alterations after T. cruzi infection. The occurrence of glomerulonephritis in the chronic phase of the disease has been reported in infections by T. cruzi. The pathphysiology of renal involvement in Chagas’ disease seems to include autoimmune phenomena. T. cruzi antigens have also been identified in renal graft glomeruli and interstitium in a patient with acute form of the Chagas’ disease. The most common lesions associated with the trypanosomes are mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. The specific treatment aims to cure the infection, prevent organ lesions or their progress and decrease the possibility of T. cruzi transmission, being effective in most cases.

ConclusionRenal function deterioration is observed in patients with Chagas’ disease, but there is no currently consistent data demonstrating renal function recovery after specific treatment. Further studies are required to better investigate renal involvement in Chagas’ disease.

La enfermedad de Chagas es causada por el protozoario Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi), en la que la lesión renal es raramente descrita. El objetivo de este estudio es describir las características de la lesión renal en la enfermedad de Chagas.

MétodosSe realizó una revisión de la literatura acerca de la lesión renal asociada a la enfermedad de Chagas. Una búsqueda en profundidad se llevó a cabo en las principales bases de datos médicas (PubMed y SciELO), utilizando las palabras clave «enfermedad de Chagas» y «riñón».

ResultadosLa lesión renal es una manifestación rara de la enfermedad de Chagas y hay pocos estudios sobre el tema en la literatura. Hay evidencia de alteraciones renales funcionales y estructurales después de la infección por T. cruzi. La aparición de glomerulonefritis en la fase crónica de la enfermedad ha sido reportada en las infecciones por T. cruzi. La fisiopatología de la lesión renal en la enfermedad de Chagas parece incluir fenómenos autoinmunes. Antígenos de T. cruzi también se han identificado en los glomérulos del riñón trasplantado y el intersticio en un paciente con la forma aguda de la enfermedad de Chagas. Las lesiones más comunes asociadas con los tripanosomas son glomerulonefritis proliferativa mesangial y glomerulonefritis membranoproliferativa. El tratamiento específico tiene como objetivo curar la infección, prevenir lesiones de órganos o de sus progresos y reducir la posibilidad de transmisión de T. cruzi, siendo eficaz en la mayoría de los casos.

ConclusiónEl deterioro de la función renal se observa en pacientes con enfermedad de Chagas, pero no hay actualmente datos consistentes que evidencien recuperación de la función renal después del tratamiento específico. Se requieren más estudios para mejor investigar la lesión renal en la enfermedad de Chagas.

Chagas’ disease or American Trypanosomiasis is caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, and its vectors are insects of the family triatomides (Triatoma infestans, Rhodnius prolixus and Panstrongylus megistus) [1–3]. Transmission occurs from the contact of T. cruzi with blood, trough the insect's feces thrown in the patients’ skin. Transmission can also occur through oral ingestion of parasites. Transfusion through blood or transplanted organs rarely occurs [3–6]. Complications of Chagas disease are mainly related to the gastrointestinal tract (megacolon and megaesophagus) and heart (Chagas heart disease). Renal involvement is seldom described, so that we have performed a literature review aiming to describe what is known about Chagas disease-associated kidney injury.

EpidemiologyChagas disease is a common tropical disease in developing countries, described in 1909 by Carlos Chagas, and is endemic in nearly all countries of Latin America. It is estimated that there are over 12 million infected individuals in Latin America, with more than 60 million of individuals in this region at risk of transmission, of which 1,600,000 only in Brazil [7–10]. Since 1975 a nationwide program for the control of vector-borne disease in Brazil has been systematized, with indicators showing results for the virtual elimination of the main species of the disease vector in the country, the T. infestans, with some sources of vectors still remaining in the northeast state of Goias and southern Tocantins, in the region of Além São Francisco, in Bahia, in northern Rio Grande do Sul state and in southeastern Piauí [7,8,11,12]. Currently, the epidemiological profile of the disease in Brazil is characterized by a new scenario, with a prevalence of chronic cases resulting from infections acquired in the past and acute Chagas disease outbreaks related to consumption of contaminated food and some isolated cases of vectorial transmission, outside the home environment, in the Amazon region. The number of Chagas disease cases showed a significant reduction in recent years, from 30 million in the 1990s to 10 million in 2006, with an annual incidence decreasing from 700,000 to 41,000 cases and deaths from 45,000 to 12,500 cases [9,13].

PhathophysiologyLesions found in Chagas’ disease result from the inflammatory response, cell damage and fibrosis induced by the parasite. This is usually intense in the acute phase, with several cycles of intracellular parasite multiplication, and less pronounced in the chronic phase, in which the infection is partially controlled by the immune response [10,14].

The disease is characterized by the involvement of the parasympathetic nervous system and, to a lesser extent, by the sympathetic nervous system, due to neuronal damage associated with inflammation and the immune process directly or indirectly caused by the T. cruzi[12–14]. Moreover, antibodies act as neurotransmitter receptor agonists, desensitizing them and leading to neurotransmitter-action blocking. The fibrosis occurs slowly and gradually [15–17].

Clinical manifestationsThe disease has two clinical presentations, one in the acute phase, usually asymptomatic, but in some situations it presents with significant symptoms, such as fever, generalized lymphadenopathy, edema, hepatosplenomegaly, myocarditis and meningoencephalitis in the moderate or severe forms of the disease [12]. The incubation period is 1–2 weeks, but in patients that received solid organs or blood transfusions from infected donors, this period can be longer, around 4 months [16–19]. The acute form can be mild and fatal in less than 5% of the cases. A small number of patients may experience heart muscle involvement with the development of severe myocarditis and invasion of the central nervous system associated with meningoencephalitis. The acute picture tends to resolve spontaneously over a period of four to six weeks, followed by the indefinite phase of the disease. This phase is usually asymptomatic with low levels of parasitemia in the blood associated with antibodies against T. cruzi antigens. However, many individuals may have, over time, signs of cardiac or gastrointestinal involvement before symptom onset [1–3].

The chronic phase of the disease includes the indeterminate, cardiac or gastrointestinal forms. Typically, a decrease in parasitemia is observed, which occurs approximately eight to twelve weeks after the infection, if no antiparasitic therapy is initiated. Many patients also develop megaesophagus, megacolon or both, manifested as dysphagia, regurgitation, aspirations and constipation. Some patients remain in the indeterminate phase of the disease for the rest of their lives [1–3].

DiagnosisParasitological tests are not routinely used in the chronic phase of the disease due to low parasitemia and thus, serological tests that detect antibodies against T. cruzi are used. The diagnosis of infection is confirmed by, at least two different serological tests, with the most often used being the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) and indirect hemagglutination (IHA). The sensitivity and specificity of the first two tests is higher than 99.5% and between 97 and 98%, respectively. The IHA test has a sensitivity of 97–98%, and specificity of 99% [4,5,12].

Approximately 10–30% of infected individuals develop the chronic form of the disease, commonly characterized by chagasic cardiopathy. Chronic chagasic cardiopathy is often detected through electrocardiographic alterations, with the most common being the complete right-bundle branch block associated with left anterior hemiblock. Atrioventricular block (AVB), sinus node dysfunction and nonsustained or sustained ventricular tachycardia can be found. At advanced stages, marked cardiomegaly with increase in the right cavities associated with slight or absent pulmonary congestion can be seen on chest X-rays. The echocardiogram allows the assessment of the contractile performance of the left and right ventricles, the presence of aneurysms, intracavitary thrombi and the presence of diastolic dysfunction.

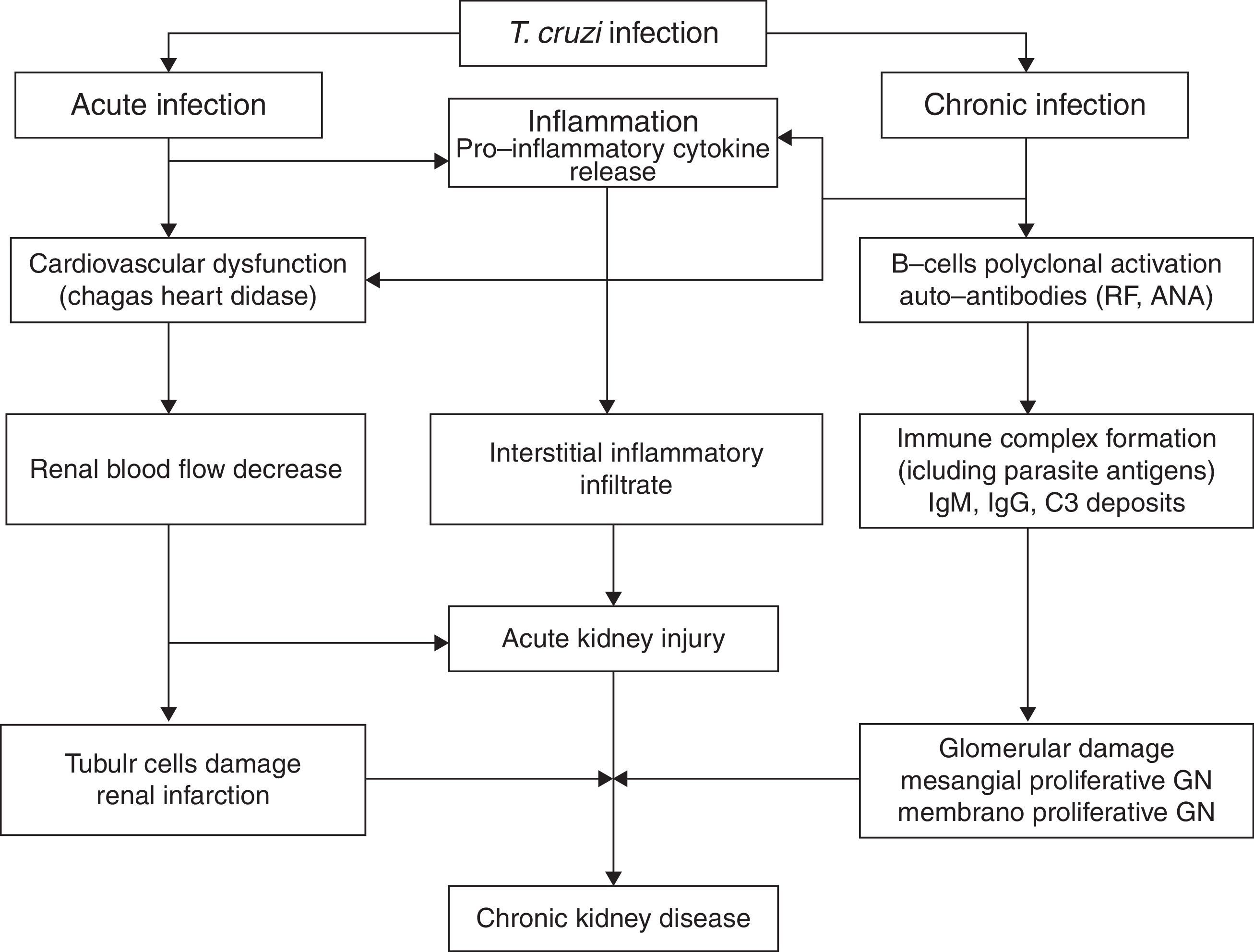

Renal involvement in Chagas’ diseaseAcute phaseT. cruzi is characterized by the ability to parasitize a wide variety of host cells, including renal cells [12,17]. Renal involvement is a rare manifestation of Chagas’ disease, and there are few studies on the subject in literature [19–23]. There is evidence of functional and structural renal alterations after T. cruzi infection, whether associated with decreased renal blood flow or damage to the proximal tubule cells, in addition to significant renal interstitial inflammatory infiltrate. An increase in kidney size is observed, associated with increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide (NO). Moreover, there may be decreased renal function, especially when there is infection with a high parasite load [19,20]. Renal lesion in the acute phase occurs around the sixth day of acute infection and is associated with cardiovascular dysfunction due to decreased renal blood flow, which has shown by studies that demonstrated the same lesion in ischemia and reperfusion lesion models [20]. The lesion is not related to the parasite presence or multiplication, with signs of the parasite being found only after 15 days of disease [3,22]. Acute kidney injury is a complication described in acute Chagas’ disease and it is an important marker of poor prognosis [13,19–22].

The occurrence of glomerulonephritis in the chronic phase of the disease has been reported in infections by T. cruzi, as well as other species of trypanosome, such as the African type [23–28]. The subspecies T. Bruzei, although it does not infect humans, causes disease with glomerular involvement in many mammals. Due to this fact, this trypanosomatid is used in several experimental models to study the mechanisms involved in glomerulonephritis secondary to trypanosomiases [23–25].

The pathophysiology of renal involvement in Chagas’ disease seems to include autoimmune phenomena. The detection of rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in experimental studies in rats infected with T. cruzi shows that the glomerular deposits in Chagas’ disease not only consist of immune complexes containing parasite antigens, but also autoantibodies. These autoantibodies are manifested by polyclonal activation of B cells [14].

In recent experimental studies, there was no significant loss of kidney function in rats infected with T. cruzi[20]. Histopathological analysis showed discrete proximal tubular damage and glomerular atrophy, associated with mild inflammatory infiltrate [21]. Intracytoplasmic amastigote forms have been identified in renal tissue from a transplanted patient [28]. T. cruzi antigens have also been identified in renal graft glomeruli and interstitium in a patient with acute form of the Chagas’ disease [29]. Disease reactivation is important after solid-organ transplants in patients from endemic areas [17].

Chronic phaseOliveira et al. [23], in 2009, demonstrated the presence of severe renal lesion characterized by early glomerular deposition of IgM with intense inflammatory renal response promoting the formation of immune complexes resulting in glomerulopathy with impaired renal function. The mechanism of the deposit of immune complexes against T. cruzi antigens, present in the glomerulus, is not completely understood [19]. According to recent studies, it seems to be mediated by immune complexes containing parasite antigens and rheumatoid factor (RF), demonstrated through deposits of Ig, C3 and T. cruzi antigens, found mainly in the mesangium at immunofluorescence, and characterized by electron-dense mesangial deposits and in paramesangial areas [19]. Renal infarction has also been described in the chronic form of Chagas’ disease and is more common when associated with heart failure [11,27].

Several T. cruzi antigens, such as B13, cruzipain and Cha, cause cross-reaction with the host's antigens in B or T cells. When the immunization with these antigens and/or the passive transfer of self-reactive T lymphocytes are carried out in mice, clinical disorders similar to those found in patients with Chagas’ disease are found [19].

The glomerular lesion in the chronic phase of Chagas disease is associated with deposits of IgM, IgG and C3 in the mesangium causing proliferation, which can be viewed through immunofluorescence [19]. The antigens of T. cruzi and the rheumatoid factor are found in serum levels as well as in the glomerulus, forming complexes with IgG and C3. Even though the disease progression and the serum levels of the parasite antigens decrease, the renal levels remain stable together with an increase of rheumatoid factor levels found in glomeruli, thus stimulating the mesangial proliferation [20]. This mesangial cell growth is mediated by secondary deposition of immune complexes [20]. Thus, the most common lesions associated with the trypanosomes are mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis [20,21].

Electron-dense deposits can be observed at the electron microscopy [20,21]. Renal infarction has also been described in chronic Chagas’ disease [29]. In one review of 78 autopsies of patients with the chronic form of Chagas’ disease, 24.4% developed renal infarction, more common among those with heart failure (52, 6%) [29]. Disease reactivation is important after solid-organ transplants in patients from endemic areas. The pathophysiology of kidney injury associated with Chagas’ disease is illustrated in Fig. 1.

TreatmentThe treatment of Chagas’ disease includes supportive care, such as interruption of professional, school or sports activities, at the physician's discretion, free diet, but avoiding alcohol. Specific treatment is carried out with benznidazole, which is the drug of choice. Nifurtimox can be used as an alternative in cases of intolerance to benznidazole [10]. In the acute phase, treatment should be performed in all cases, as soon as possible after diagnostic confirmation. The specific treatment is effective in most acute cases, i.e., >60%. The specific treatment aims to cure the infection, prevent organ lesions or their progress and decrease the possibility of T. cruzi transmission. Treatment with Benznidazole consists of 100mg tablets that should be taken in 2 or 3 daily doses for 60 days. In patients with the indeterminate form of the disease or with established chagasic cardiopathy, the indication of specific treatment is controversial. There is experimental evidence that suggest cardiopathy progression attenuation. The specific treatment aims to cure the infection, prevent organ lesions or their progress and decrease the possibility of T. cruzi transmission, being effective in most acute cases, i.e., >60%.

In summary, renal function deterioration is observed in patients with Chagas’ disease during treatment, but there is no currently consistent data demonstrating renal function recovery after specific treatment. Further studies are required to better investigate renal involvement in Chagas’ disease.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.