Amiodarone is a potent class III antiarrhythmic drug used for both supra and ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Due to its high iodine content and similar structure to thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), abnormalities in thyroid function are common (hyper/hypothyroidism) in patients taking amiodarone, especially with long term use. We present the case of a patient with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis (AIT), refractory to medical therapy, which required total thyroidectomy for symptomatic control.

La amiodarona es un potente antiarrítmico clase III, indicada en el tratamiento de taquiarritmias supra y ventriculares. Debido a su alto contenido en yodo y estructura similar a la tiroxina (T4) y triyodotironina (T3), son frecuentes las alteraciones en la función tiroidea (hiper/hipotiroidismo) en pacientes que la consumen. Presentamos el caso de un paciente con tirotoxicosis inducida por amiodarona (TIA), refractaria a terapia médica, que precisó tiroidectomía total para control sintomático.

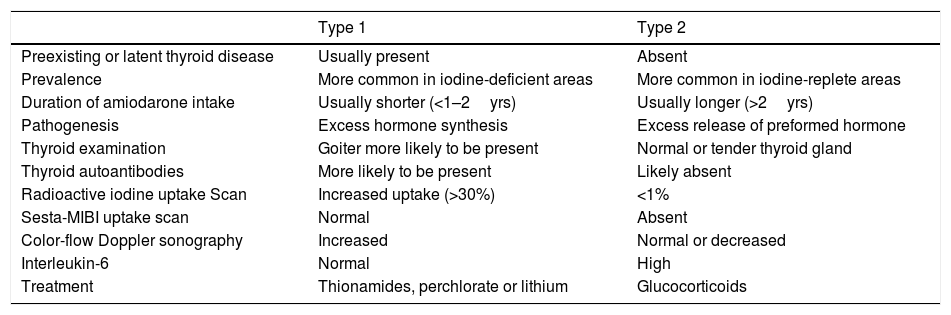

Amiodarone is a potent class III antiarrhythmic drug used for both supra and ventricular tachyarrhythmias, with a high iodine content (37.5% of its mass),1,2 and it has a similar structure to thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), which is translated in a high rate of thyroid dysfunctions (15–20%).3,4 Amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis (AIT) typically occurs in iodine-deficient areas of the world.5,6 In Europe, amiodarone-induced thyroid dysfunction affects 3 over 100 treated patients per year, and AIT is the major form.7 The differential diagnoses of AIT are classified as type 1 and type 2. Type 1 AIT is more likely to occur in subjects with underlying thyroid pathology as a direct effect of the iodide load from the amiodarone therapy. Type 2 AIT is caused by direct toxic effect of amiodarone, which causes a destructive thyroiditis and it typically occurs in patients without underlying thyroid disease (see Table 1). Sometimes, in the same subject, both mechanisms can be present.1,3,8 Amiodarone is very lipophilic and it has a long elimination half-life (107 days), mainly due to its storage in adipose tissue, and its toxic effects may persist or even occur several months after its discontinuation.1,8,9 We present the case of a patient with Type 2 AIT, who failed to respond to therapy medical conventional, and total thyroidectomy was performed as permanent solution.

Comparison between amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis type 1 and type 2.1,3,7

| Type 1 | Type 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Preexisting or latent thyroid disease | Usually present | Absent |

| Prevalence | More common in iodine-deficient areas | More common in iodine-replete areas |

| Duration of amiodarone intake | Usually shorter (<1–2yrs) | Usually longer (>2yrs) |

| Pathogenesis | Excess hormone synthesis | Excess release of preformed hormone |

| Thyroid examination | Goiter more likely to be present | Normal or tender thyroid gland |

| Thyroid autoantibodies | More likely to be present | Likely absent |

| Radioactive iodine uptake Scan | Increased uptake (>30%) | <1% |

| Sesta-MIBI uptake scan | Normal | Absent |

| Color-flow Doppler sonography | Increased | Normal or decreased |

| Interleukin-6 | Normal | High |

| Treatment | Thionamides, perchlorate or lithium | Glucocorticoids |

Our patient is a 67-year-old white man with history of hypertension, lipid disorder and atrial fibrillation (AF), who developed minimal effort dyspnea secondary to AF with rapid ventricular rate. One month earlier, he had been diagnosed from amiodarone induced thyrotoxicosis and had stopped amiodarone therapy. In addition, therapy with methimazole (20mg/day) and oral prednisone tapered dose had been started.

On admission, he was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Physical examination revealed warm and sweaty skin; no palpable or visible goiter and no signs or symptoms for thyroid-associated orbitopathy were found. The auscultation showed irregular heartbeat and bibasilar crackles. Furthermore, he related unexplained weight loss of 5% of body weight over the last two or three months.

Complementary testsECG: AF with a rate of 115bpm. 0° axis. Flattened T waves in anterior and lateral leads.

Echocardiogram: The left ventricular internal size is increased. Left ventricular ejection fraction is >55% by visual estimation. Left atrium is not dilated. No evidence of valvular heart disease.

Thyroid ultrasound: The thyroid gland is normal in size and echogenicity. There are no discrete nodules evident. No lower cervical lymphadenopathy. Color-Doppler showed decreased blood flow.

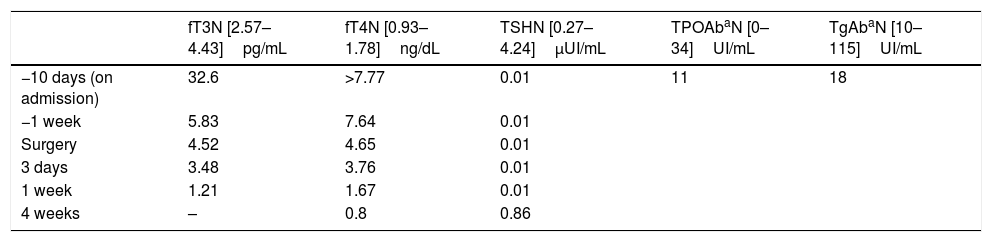

Admission laboratory tests confirmed thyrotoxicosis (see Table 2). Thyroid autoantibodies were within the normal range (see Table 2). Hemogram and biochemical parameters, including cardiac markers (troponin and creatine phosphokinase) did not show significant alterations.

Free T3, free T4, TSH and thyroid antibodies values during hospitalization.

Scintigraphy was not performed, since this test which is not available in our center, and the patient's clinical status would not make it possible.

Treatment, outcome and follow-upInitially, medical therapy was intensified with high dose of anti-thyroid drugs (methimazole 40mg/day), intravenous steroids (methylprednisolone 60mg/day) and propranolol (100mg/day), adopting a rate control strategy for his atrial fibrillation. Good clinical response was shown on first instance, specially dyspnea symptoms and heart palpitations.

Three days later, the patient presented a clinical worsening, he reported increasing fatigue, fever and palpitations. Heart acute failure was diagnosed due to difficult-to-control atrial fibrillation and he was started on digoxin and loop diuretics. Moreover, methimazole was stopped and therapy with propylthiouracil (PTU) was started, as it interferes with the conversion of T4–T3. Propranolol was changed to Atenolol, as it is a cardioselective beta-blocker. Taking into account the clinical-analytical worsening, surgical intervention was pursued (total thyroidectomy) and potassium perchlorate was added to treatment, which minimizes intrathyroid iodine content by competitively inhibiting thyroidal iodine intake. Until surgery, the patient remained hemodynamically stable, but he continued to have evening fevers due to thyrotoxicosis, discarding any underlying infection.

Ten days after admission, total thyroidectomy was performed. The patient's intra- and postoperative course was unremarkable. The patient was clinically and biochemically euthyroid one week after the thyroidectomy (see Table 2 and Fig. 1). Replacement doses of levothyroxine were subsequently started (50mcg/day) and were discharged from hospital.

One month after surgery, we did a follow-up visit and the patient remained clinically asymptomatic. Replacement dose of levothyroxine was adjusted (100mcg/day), according to the levels of free T4, which were low (see Table 2 and Fig. 1). Digoxin was discontinued on cardiology follow-up consultation due to slight bradycardia on ECG.

DiscussionWe present a case of type 2 AIT refractory to glucocorticoids and high dose of anti-thyroids drugs. The patient was suspected of having “mixed thyrotoxicosis”, since thyroid antibodies were within the normal range and no response to glucocorticoids was shown. However, final pathology report revealed follicles exhausted enlarged with flattened surface epithelium, vacuolated cytoplasm and pyknotic nucleus. Aggregates of foamy histiocytes were found within the injured follicles, as well as in the adjacent interstitium (see Figs. 2–4). These changes are typical for amiodarone-induced thyroid injury and it can be classified as type 2 AIT, since there was no evidence of latent thyroid disease.10

Treatment of AIT depends on the type as well as the severity of thyrotoxicosis on presentation, but it usually responds to medical therapy, especially if it is an type 2 AIT.3,8,10 Severe AIT, like our case, requires more urgent intervention. Sometimes, an association of thionamides, perchlorate and glucocorticoids is necessary to control severe thyrotoxicosis.8,11,12 Alternative treatments with lithium or iopanoic acid have been described, but with low evidence.3

In our patient, in spite of medical management with thionamides and glucocorticoids, left heart failure was diagnosed, and surgical treatment was required. In the event of worsening thyrotoxicosis in spite of medical management, total or near-total thyroidectomy may be warranted.13–15 There have been over 100 reported cases of total thyroidectomy for AIT.16 Most are performed under general anesthesia with surprisingly low morbidity and mortality.14,16 There are also case reports of minimally invasive thyroidectomy being performed under local anesthesia, but this surgical procedure is not very common.17

ConclusionAmiodarone commonly causes thyroid dysfunction. It is recommended that patients are taking amiodarone be screened with TSH levels periodically. Most cases of AIT are amenable to medical therapy with thionamides and/or glucocorticoids. In those patients who do not respond to these measures or are too critically ill to allow for a long enough course of medical management, thyroidectomy is a viable therapeutic option.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interests.