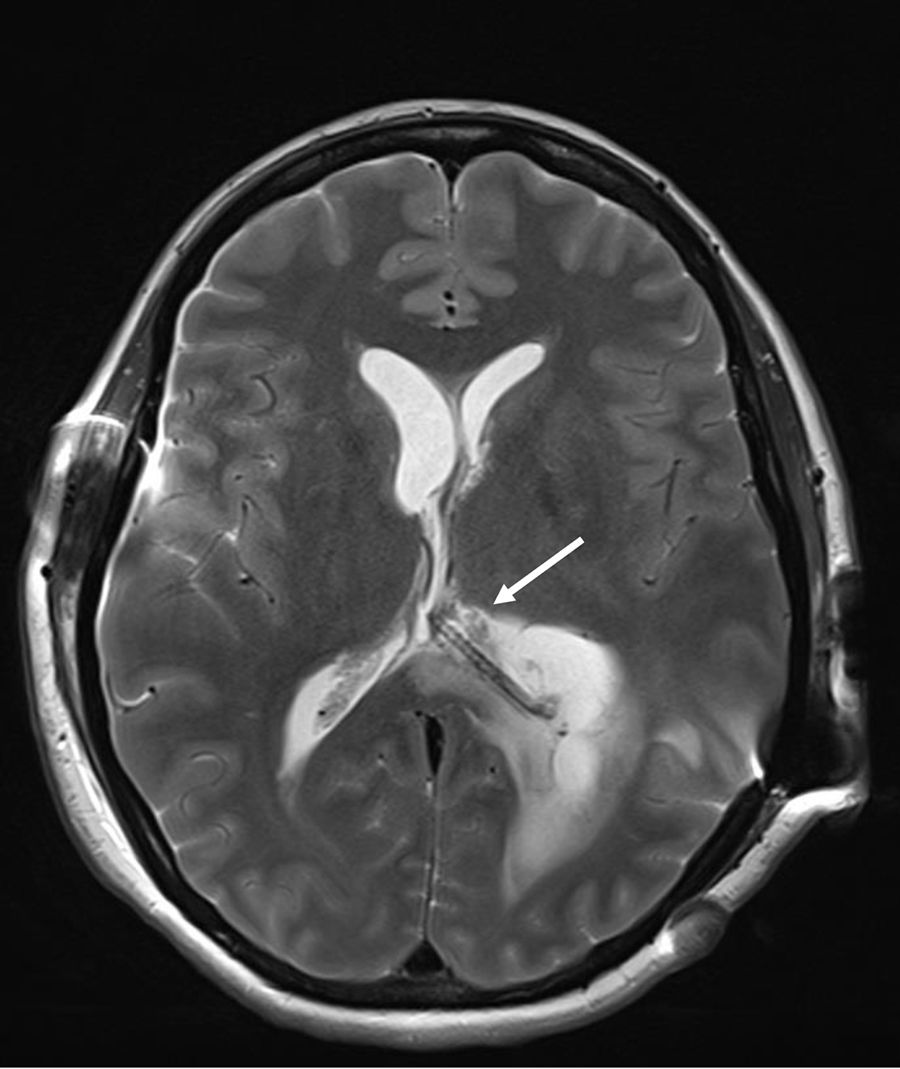

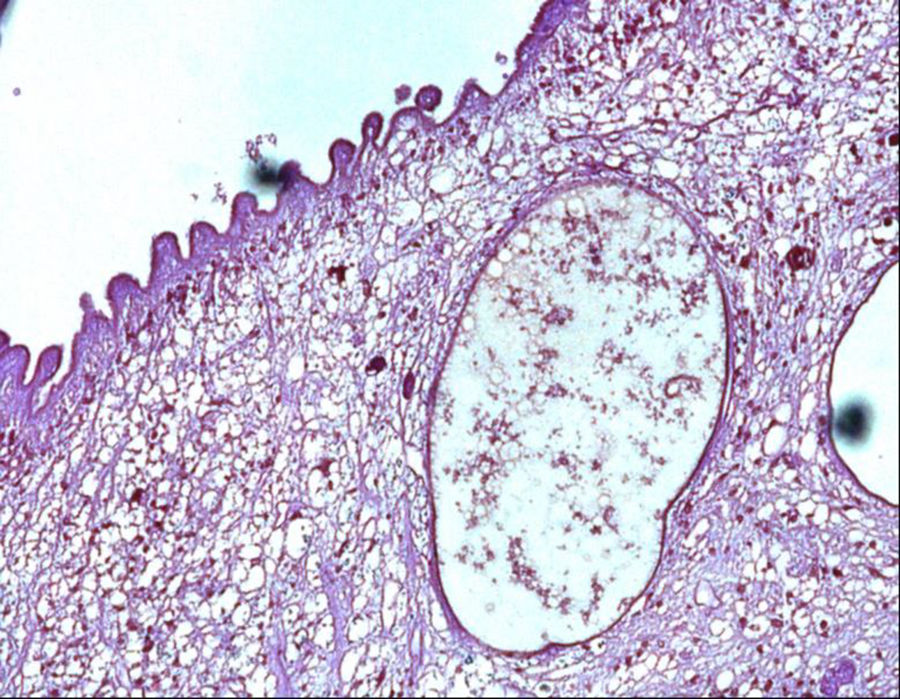

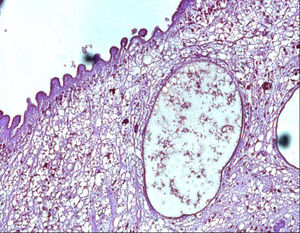

A 40-year-old woman from Ecuador presented to the emergency department (ED) with headache, vomiting, drowsiness, confusion and incoherent speech. She lives in Spain since 2001 and she carries a ventriculoperitoneal shunting since 1993, placed in Ecuador because an obstructive hydrocephalus of unknown origin. In 2013, she consulted repeatedly the ED because hydrocephalus valve mismatches requiring a valve replacement. Laboratory test in peripheral blood showed C-reactive protein level of 34.90mg/dl and 7800neutrophils/dl. Cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed 260red blood cells/μl, 300leukocytes/μl with a differential of 42% of eosinophils, a protein level of 1.5g/l and positive xanthochromia. Gram stain of CSF showed no microorganisms and was inoculated onto chocolate blood agar and blood agar plates and incubated in an aerobic atmosphere at 37°C with negative result after 48h. Computed tomography (CT) confirms valve dysfunction excluding left ventricular and showed some parenchymal and periventricular calcifications. The patient underwent emergency valve replacement with proximal catheter placement. MRI postintervention (Fig. 1) showed some punctate supratentorial calcifications and two spherical multi-septate lesions with a CSF similar density placed periventricular in the left ventricle. One of the multi-septate lesions supposedly responsible of the symptoms was removed surgically (Fig. 2) and some histological cuts were made of it (Fig. 3).

A sample of CSF was sent to the Parasitology Unit of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid, Spain) to detect by enzyme-linked immunoassay1Taenia solium antigen and immunoglobulin G (IgG). Both antigen and IgG against T. solium tests were positive and it was confirmed with a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeted to a T. solium DNA on CSF.2 Parenchymal and periventricular calcifications, two spherical multi-septate lesions, the presence of anticysticercal antibodies in CSF and been residing in an endemic country, where the patient had already showed intracranial hypertension, lead to the neurocysticercosis diagnosis.

Antiparasitic drugs were no recommended at this stage of the disease and the treatment with parenteral dexamethasone was needed till a progressive neurological improvement. Sequelae included language disorder and slow mental activity that improved with neurocognitive rehabilitation.

Final commentDifferential diagnosis of a cystic brain lesion must contemplate primary neoplasm, metastasis (lung and breast neoplasms are the most common cause), brain abscess, tuberculoma and neurocysticercosis (NCC).

Cysticercosis is defined as the infection caused by the larval stage of T. solium once swallowing eggs found in contaminated food, being in contact with human feces of a person who has an intestinal tapeworm or by autoinfection. T. solium is a two-host zoonotic cestode and human could be definitive and intermediate host; the last case is when cysticercosis occurs. T. solium is found worldwide and parasitosis occurs in regions where humans eat undercooked pork or live in close contact with pigs. NCC is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, most part of Asia, included China, and Latin America countries. NCC will be developed when onchospheres reach the central nervous system which can be classified in parenchymal and extraparenchymal, depending on the location of the cysts. Seizure is the most common clinical manifestation of parenchymal cysticercosis, caused in 30% of cases by NCC in endemic zones, included Latin America countries.3,5 Extraparenchymal NCC occurs when cysts are placed in subarachnoid space or in the ventricular system, leading obstruction of CSF flow, producing intracranial hypertension and hydrocephalus. Mobile extraparenchymal cysts can be the reason of irregular symptoms, such as intracranial hyper/hypotension and sudden death.3,4 Mononuclear pleocytosis and eosinophilia in CSF could be detected in patients with active inflammation.

In 2017, diagnostic criteria for NCC were edited5,6 and organized in three categories with many levels of certainty: absolute, neuroimaging and clinical/exposure criteria. Histological confirmation of parasites, evidence of subretinal cysts, and demonstration of the scolex within a cyst are absolute criteria for NCC diagnosis. Cystic lesions without scolex, multilobulated cysts and calcifications are categorized as neuroimaging major criteria. Clinical/exposure criteria include detection of anticysticercal antibodies or cysticercal antigens by enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and residing in endemic areas.1,6–8 A definitive diagnosis can be made in those having one absolute criteria or two major neuroimaging criteria plus exposure criteria.5,6

Patients with extraparenchymal cysts and hydrocephalus secondary to the NCC are candidates to place ventricular shunts or to remove cysts from the ventricles. However, a high mortality exists (up to 50% in two years) related to the number of surgical interventions to change the shunt.2,3 There is no evidence antiparasitic drugs could contribute to improve calcified cysts resolution. Viable and degenerating cysts can promote a severe immunological response and acute episodes should be treated with corticosteroids (e.g. dexamethasone).5,6

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors thank Silvia Roure and Parasitology Unit of Instituto de Salud Carlos III for their work and to guide us through the process.