SI: Minimally invasive surgery of the abdominal wall

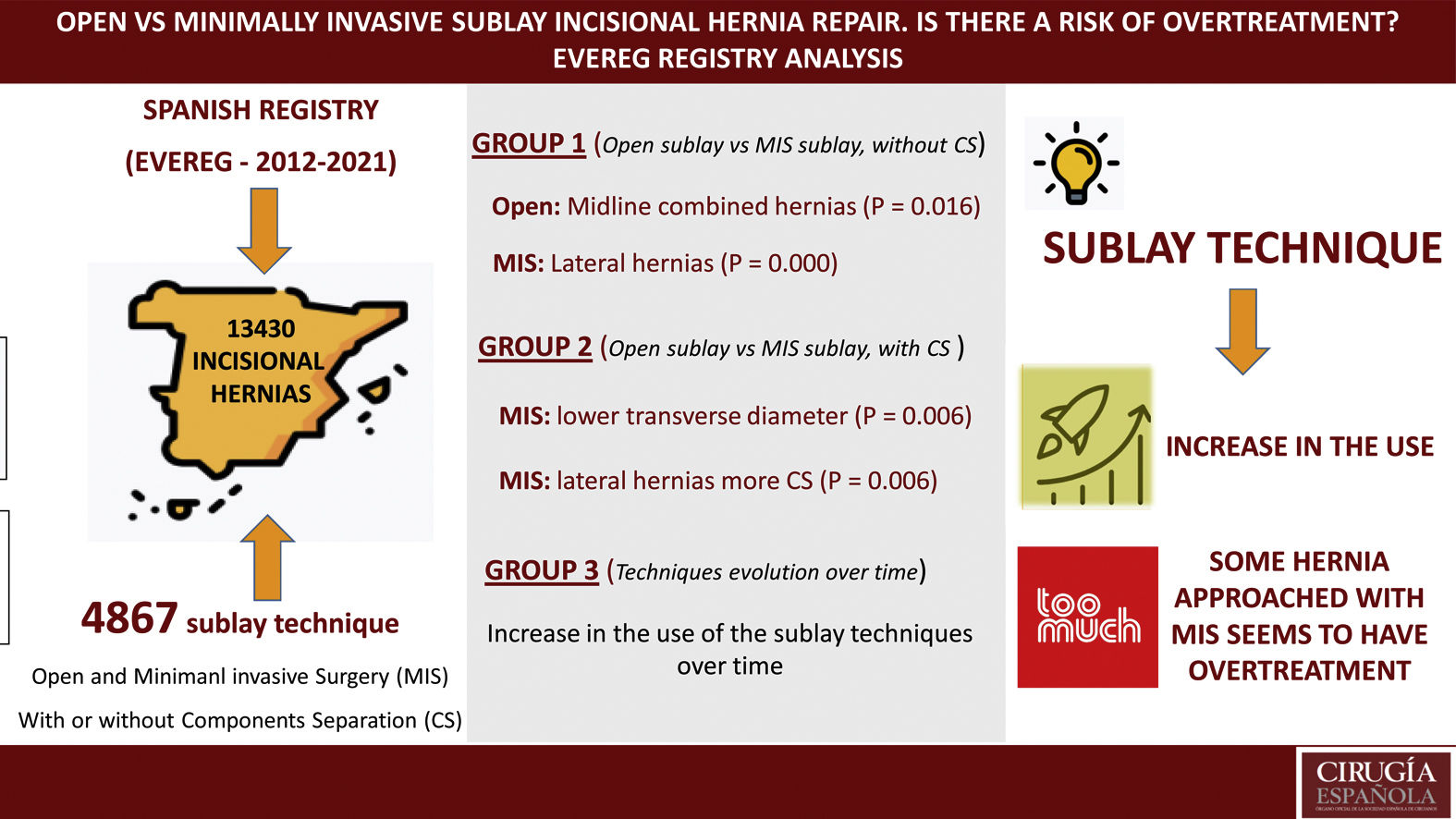

More infoIncisional hernia (IH) is a very common surgical procedure. Registries provide real world data. The objective is to analyze the open and minimally invasive (MIS) sublay technique (with or without associated components separation [CS]) in IH cases from the EVEREG registry and to evaluate the evolution over time of the techniques.

MethodsAll patients in EVEREG from July 2012 to December 2021 were included. The characteristics of the patients, IH, surgical technique, complications and mortality in the first 30 days were collected. We analyzed Group 1 (open sublay vs MIS sublay, without CS), Group 2 (open sublay vs MIS sublay, with CS) and Group 3 where the evolution of open and MIS techniques was evaluated over time.

Results4867 IH were repaired using a sublay technique. Group 1: 3739 (77%) open surgery, mostly midline hernias combined (P = .016) and 55 (1%) MIS, mostly lateral hernias (LH) (P = .000). Group 2: 1049 (21.5%) open surgery and 24 (0.5%) MIS. A meaningful difference (P = .006) was observed in terms of transverse diameters (5.9 (SD 2.1) cm for the MIS technique and 10.11 (SD 4.8) for the open technique). The LH MIS associated more CS (P = .002). There was an increase in the use of the sublay technique over time (with or without CS).

ConclusionIncreased use of the sublay technique (open and MIS) over time. For some type of hernia (LH) the MIS sublay technique with associated CS may have represented an overtreatment.

La hernia incisional (HI) es un procedimiento quirúrgico muy frecuente. Los registros ofrecen datos del mundo real. El objetivo es analizar la técnica sublay abierta y mínimamente invasiva (MIS), con o sin separación de componentes (SCC) en los casos de HI del registro EVEREG y evaluar la evolución en el tiempo de las técnicas.

MetodosSe incluyeron todos los pacientes en EVEREG desde julio 2012 a diciembre 2021. Se recogieron las características de los pacientes, HI, técnica quirúrgica, complicaciones y mortalidad en los 30 primeros días. Se analizó un Grupo 1 (sublay abierta vs sublay MIS, sin SCC), un Grupo 2 (sublay abierta vs sublay MIS, con SCC) y un Grupo 3 donde se evaluó la evolución en el tiempo de las técnicas abiertas y MIS.

Resultados4867 HI fueron reparadas siguiendo una técnica sublay. Grupo 1, 3739 (77%) cirugía abierta, sobre todo hernias de línea media combinadas (P = .016) y 55 (1%) MIS, sobre todo hernias laterales (HIL) (P = .000). Grupo 2, 1049 (21,5%) cirugía abierta y 24 (0.5%) MIS. Se observó una diferencia significativa (P = .006) en cuanto a los diámetros transversales (5.9 (DE 2.1) cm para la técnica MIS y 10.11 (DE 4.8) para la técnica abierta). Las HIL MIS asociaron más SCC (P = .002). Hubo aumento del uso en el tiempo de la técnica sublay (con o sin SCC).

ConclusionIncremento del uso de la técnica sublay abierta y MIS. Para algún tipo de hernia (HIL) la técnica MIS sublay con SCC asociada puede haber representado un sobretratamiento.

Incisional hernia (IH) is a very common surgical procedure where experts differ in opinion about the most appropriate surgical technique for its repair,1 and international consensus has yet to be reached about the indication for one intervention or another.2 It is likely that one of the most important causes that justify this lack of agreement is weak evidence (i.e., data), since randomised studies in the literature that compare different techniques report their peri- and postoperative results inconsistently due to a lack of uniformity in the definition of the variables analysed.3 Recently, efforts have been made to improve this situation.4 A further piece of evidence is registries, which offer a means to capture longitudinal data in real-world practice5 and can provide rich and contextual information on the clinical behaviour of a technique or sets of techniques. Thus, specific registries on IH show a clear heterogeneity in the techniques used to repair this type of hernia.6,7

In the previous context, some authors have proposed that the open repair technique with placement of a mesh in the plane behind the rectus abdominis muscles may be the best repair technique for midline incisional hernias (MIH).8 The technique behind the rectus abdominis muscles is also called sublay, and in terms of nomenclature they are considered equivalent.9 Furthermore, the open sublay technique can be “extended” laterally beyond the rectus abdominis muscles to the region located behind the lateral musculature of the abdominal wall, associating the so-called posterior separation of components (transversus abdominis release [TAR]),10 also allowing the treatment of lateral incisional hernias (LHI). The above separation of components can also be combined with a sublay11 technique.

In recent years, the sublay technique performed through minimally invasive surgical approach (MIS) has developed to a great extent with the appearance of techniques that place the prosthesis confined to the space behind the rectus abdominis muscles without adding a TAR (mini/less open sublay [eMILOS]12 or the so-called eTEP13,14) or the placement of the prosthesis beyond the rectus abdominis muscles with associated TAR MIS.15 Some records show data in favour of the open sublay technique and the new MIS7 sublay techniques.

The primary objective of this study was to analyse the perioperative and postoperative results of the open sublay technique and MIS, associated or not with a component separation (SCC) in cases of elective IH surgery included in the EVEREG6 registry. The secondary objective was to evaluate the evolution over time of the different IH treatment techniques collected since the beginning of the registry.

MethodsPatientsEVEREG is an online prospective database accessible on the Internet (http://www.vereg.es/). Patient registration is anonymous and there are 178 participating centres throughout the country. EVEREG is permanently open to all centres that wish to participate. The registry data structure, committee approval process, and data collection system have been described previously.6 EVEREG is a database maintained by the surgeons responsible for each centre, in which patient parameters, the type of hernia, the operations and complications of each procedure performed for elective and urgent IH and for parastomal hernias (PH) are collected. Follow-up is carried out through clinical control with an appointment at one month, 6 months, one year and 2 years after surgery. Patients undergoing an open or laparoscopic sublay technique with or without an SCC and enrolled in the EVEREG from July 2012 to December 2021 were included and analysed.

VariablesSublay was defined as the placement of the repair mesh outside the abdominal cavity between the different planes of the abdominal wall (i.e., preperitoneal or retromuscular) and whether an SCC was associated or not was noted. The demographic variables collected included the patient's age and sex, body mass index (BMI: kg/m2) and whether they smoked or not. Among the comorbidities recorded in EVEREG, the presence or absence of diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was selected. The anaesthetic risk evaluated using the ASA (American Society of Anaesthesiologists) classification was recorded.

IH was classified according to its location following the criteria of the European Hernia Society (EHS), adding the concept of combined midline hernia when there were several orifices along the entire midline given the lack of consensus about these variants.16 It was identified whether there were previous repairs (recurrent hernia) or whether prehabilitation of the hernia was associated with progressive pneumoperitoneum (PPP) or injection of botulinum toxin (BT) into the abdominal wall. The transverse and longitudinal diameter of the hernia (in cm) and whether or not there were intraoperative or postoperative complications were recorded, without specifying which ones. Mortality was recorded in the first 30 days after the intervention.

The development of the study was carried out following the international clinical research guidelines (Code of Ethics and Declaration of Helsinki) and according to the legal regulations of confidentiality and data privacy according to Spanish legislation (LOPD, 2018). The local ethics committee approved the study protocol (2012/4908/I).

Analysis strategy (groups)The analysis strategy was divided into three groups. In relation to the primary objective, groups 1 and 2 were analysed. Group 1 consisted of patients with an open sublay technique without SCC vs. an MIS sublay technique without SCC, and group 2 consisted of patients with an open sublay technique with SCC vs. an MIS sublay technique with SCC.

In relation to the secondary objective, a group 3 was analysed, where the evolution over time of the proportions of open techniques and MIS was evaluated since the beginning of EVEREG, divided into 3 time periods (from 2012 to 2014, from 2015 to 2017 and from 2018 to 2021).

For the global group of patients included in EVEREG, all those with incomplete data that were not feasible for analysis were excluded. For the first two groups, cases of elective surgery using the open onlay technique, the laparoscopic IPOM, cases of PH and cases of urgent surgery were excluded. For the third group, only cases of urgent surgery and PH were excluded.

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) and qualitative variables as proportions. To analyze the association between qualitative variables, the chi-square test ((χ2) or Fisher's exact test were used, when necessary, as well as the Student t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test for quantitative variables. The normality of the distribution of the quantitative variables was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Statistical significance was established at P < .05. Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) programme (IBM Inc., Rochester, MN, USA) version 25 for Windows.

ResultsFrom July 2012 to December 2021, a total of 13,430 IH were registered in EVEREG, and of these, 3384 (25%) were excluded due to incomplete data. Of the remaining 10,046 (75%) IH, a total of 4867 (48%) were selected and repaired following a sublay technique. Of these, 3739 (77%) patients with an open sublay repair without SCC and 55 (1%) patients with an MIS sublay repair without SCC were selected for analysis group 1. The demographic characteristics of both sets of patients did not show significant differences. It was observed that combined midline hernias were more frequently performed using an open approach (P = .016) and the MIS approach was more common in lateral hernias (P = .000). There were no differences between the open technique and MIS without SCC in terms of the mean transverse or longitudinal diameter, although the former was not greater than 6.4 cm (SD: 3.7), being lower in the MIS, with a mean of 5.28 cm (SD: 3.5). There were also no differences in the prehabilitation techniques used (PPP or BT), nor in intra- or postoperative complications, which were low. The complete description of the variables studied in group 1 is shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of the sublay technique without separation of the associated components.

| Variable | Open sublay without SCC, n = 3.739 | MIS sublay without SCC, n = 55 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (Man/woman) n (%) | 1.762 (47.1)/1.977 (52.9) | 20 (36.4)/35 (63.6) | .112 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 62.5 (12.8) | 63.7 (13.4) | .073 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29.7 (5.2) | 29.6 (5.8) | .340 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 807 (21) | 17 (31) | .095 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 693 (18) | 12 (22) | .534 |

| COPD, n (%) | 536 (14) | 9 (16) | .670 |

| ASA III-IV, n (%) | 1022 (27) | 11 (20) | .225 |

| [0,1-4]Location of the hernia, n (%) (EHS classification) | |||

| M 1−2 | 741 (20) | 6 (11) | .099 |

| M 3 | 996 (27) | 12 (22) | .421 |

| M 4−5 | 321 (8,5) | 5 (9) | .894 |

| Midline combined | 1.100 (29) | 8 (14) | .016 |

| Lateral | 581 (15,5) | 24 (44) | .000 |

| Recurrent hernia | 774 (21) | 9 (16,3) | .430 |

| [0,1-4]Size of defect in cm, mean (SD) | |||

| Transversal diameter | 6.40 (3.7) | 5.28 (3.5) | .445 |

| Longitudinal diameter | 7.60 (5.3) | 5.56 (4) | .106 |

| Previous pneumoperitoneum, n (%) | 38 (1) | 3 (5.5) | .001 |

| Previous botulinum toxin, n (%) | 43 (1,1) | 41 (74.5) | .000 |

| Intraoperative complications, n (%) | 50 (1,3) | 1 (1.8) | 0,758 |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | 313 (8) | 2 (4) | 0,206 |

| Postoperative death | 4 (.1) | 0 | .808 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; EHS: European Hernia Society; MIS: Minimally invasive; p: probability; SCC: Separation of components; SD: Standard Deviation.

Regarding analysis group 2, 1049 (21.5%) were selected with an open sublay repair with SCC and 24 (0.5%) with an MIS sublay repair with SCC. In this group, patients with ASA III–IV predominated in patients with open surgery, and MIS repair with SCC for lateral hernias predominated (P = .002). A significant difference was observed in terms of transverse diameters, with a mean of 5.9 (SD: 2.1) cm for the MIS sublay technique associated with SCC and a mean of 10.11 (SD: 4.8) cm for the open sublay technique associated with SCC. The complete description of the variables studied in group 2 is shown in Table 2.

Characteristics of the sublay technique with separation of associated components.

| Variable | Open sublay with SCC, n = 1049 | MIS sublay with SCC, n = 24 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (man/woman), n (%) | 570 (54.3)/479 (45.7) | 12 (50)/12(50) | .673 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 62.6 (11.6) | 66.5 (12.3) | .368 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 30.3 (5.2) | 29.5 (4.7) | .344 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 224 (21) | 10 (42) | .017 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 238 (23) | 6 (25) | .701 |

| COPD, n (%) | 184 (17.5) | 1 (4) | .086 |

| ASA III-IV, n (%) | 339 (32) | 3 (12.5) | .039 |

| [0,1-4]Location of the hernia, n (%) (EHS classification) | |||

| M 1−2 | 86 (8) | 2 (8) | .981 |

| M 3 | 81 (8) | 2 (8) | .911 |

| M 4−5 | 71 (7) | 0 | .187 |

| Midline combined | 627 (60) | 10 (42) | .074 |

| Lateral | 184 (17) | 10 (42) | .002 |

| Recurrent hernia | 336 (32) | 8 (33.3) | .892 |

| [0,1-4]Type of SCC | |||

| Anterior | 303 (28) | 0 | .001 |

| Posterior | 736 (71) | 24 (100) | .001 |

| Combined | 10 (1) | 0 | .630 |

| [0,1-4]Size of defect (cm), mean (SD) | |||

| Transversal diameter | 10.11 (4.8) | 5.9 (2.1) | .006 |

| Longitudinal diameter | 12.9 (6.6) | 7.3 (4.9) | .000 |

| Previous pneumoperitoneum, n (%) | 63 (6) | 0 | .215 |

| Previous botulinum toxin, n (%) | 121 (11.5) | 0 | .077 |

| Intraoperative complications, n (%) | 33 (3) | 0 | .377 |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | 218 (21) | 1 (4) | .045 |

| Postoperative death | 6 (.5) | 0 | .710 |

ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; EHS: European Hernia Society; MIS: Minimally invasive; p: probability; SCC: Separation of components; SD: Standard Deviation.

All MIS techniques in groups 1 and 2 were performed using conventional laparoscopic technology. No MIS technique using robotic technology was reported in this analysis.

The evolution over time of the different elective techniques included in EVEREG showed a progressive increase in the percentages of sublay techniques, both those associated with and those not associated with an SCC. The use of MIS techniques has also followed a progressive decrease in the percentages of the onlay technique (IPOM) with an increase in the sublay technique and the incorporation of MIS surgery associating SCC since 2015. The evolution over time of open techniques and MIS is represented in Figs. 1 and 2.

The recurrence of the complete sublay group at 24 months of follow-up was 3.4%. An adequate calculation of recurrence by subgroups was not possible due to losses in that period of time greater than 50%.

DiscussionAccording to the findings of our study, from the beginning of the EVEREG registry until the end of the period of our analysis there has been a change in the trend of the percentages of surgical techniques for the treatment of IH. Regarding open techniques, in the first years of EVEREG the onlay technique predominated (both without SCC and with associated SCC), which was already published in a first article about EVEREG.6 However, in the last six years there has been a predominance in the percentages of use of the open sublay technique (both with and without associated SCC).

Although there is no consensus among experts regarding the most appropriate surgical technique for the repair of an IH,1 nor an international consensus about the indication of one intervention or another,2 there is growing evidence that sublay repair can be associated with the lowest IH recurrence rates.17,18 The evolution towards the open sublay technique in our registry may be based on several aspects. On the one hand, better knowledge and application of evidence to the usual practice of interested Spanish surgeons, thus recognising the potential benefits of this underlay technique8,11,17,18 compared to the onlay technique.19 Obviously, the onlay technique will continue to have its indications,19 and it should not be discarded from the therapeutic arsenal for the repair of IH. Alternatively, another very important aspect that may have favoured the use of the open sublay technique may be better knowledge and training of surgeons in Spain in the anatomy of the abdominal wall, favouring the application of techniques that are associated with the development of more complex plans where to place the repair mesh. The increase in the coding of the open sublay technique is not exclusive to our registry, as it aligns with the IH repair trend of other important registries in our European area, such as the Herniamed registry.7

We are not going to focus here on the general characteristics of patients with SCC-associated open sublay technique, since they are patients with complex wall defects associated with a high level of perioperative complications, as recently described in another analysis in EVEREG in relation to patients with a SCC.20 However, we would like to highlight that the open sublay technique without associated SCC was performed in patients with transverse diameters of the defect that were not excessively large (mean diameter of 6.4 cm; W2 according to the EHS16 classification), suggesting that it is used for IH of medium or even smaller diameters, in accordance with data from recent systematic reviews.18

Regarding laparoscopic techniques, it is also interesting to observe here the parallelism with other registries in our environment.7 In EVEREG, a decrease in the onlay laparoscopic technique (i.e., IPOM) has is also been observed in the last six years in comparison to an increase in sublay laparoscopic techniques with and without associated SCC. The better knowledge of the anatomy of the abdominal wall and the description of manoeuvres that connect/expand the retromuscular space crossing behind the midline (crossover)13,14 have allowed the placement of the mesh outside the abdominal cavity of identical manner to the open sublay technique, thus avoiding the potential complications of an intra-abdominal mesh associated with a laparoscopic IPOM repair.21 The previous context may justify the change in trend in MIS techniques in our registry.

When we specifically compared the different groups of patients in EVEREG with associated sublay technique, we observed that for group 1 (patients with an open sublay technique without SCC vs. a MIS sublay technique without SCC) the demographic characteristics and anaesthetic risk did not show up any differences among them, although the MIS technique was significantly reserved for LIH and the open technique for combined MIH. In the first case (LIH), the selection of the MIS approach may be justified by the fact that the mesh is placed with better overlap with respect to the hernial orifice, especially hernias adjacent to bone edges. The joint guidelines of the American Hernia Society (AHS) and the EHS on the treatment of hernias in rare locations are not conclusive in recommending an open or laparoscopic approach,22 and other guidelines found in the literature recommend the treatment of choice as MIS surgery with sublay mesh placement when dealing with lateral hernias with “small or medium size”23 or “small defect (<5 cm),24 similar to the data found in our registry, where the mean transverse diameter for patients with MIS approach without SCC was 5.28 (SD: 3.5) cm. In the second case (combined MIH), the greater use of an open sublay technique could be justified by a larger mean transverse diameter (6.40 [SD: 3.7] cm) and perhaps by the potential disadvantage of conventional laparoscopic surgery. handling more complex defects due to workspace limitations.11 A fact worth highlighting in this group 1 was the finding of a greater use of prehabilitation with BT for the majority of patients with MIS surgery. The use of BT as an adjuvant to MIS surgery has very limited evidence, although it may represent an interesting area of clinical research.25 There were no differences in complications between open surgery and MIS in group 1.

In the analysis of group 2 (open sublay technique with SCC vs an MIS sublay technique with SCC) demographic differences were also not observed, except for there being more smokers in MIS cases and greater anaesthetic risk in open cases. As expected,20 the SCC-associated open sublay cases were of greater complexity, with a mean transverse diameter of 10.11 (SD: 4.8) cm and with greater preoperative prehabilitation than the MIS cases, where prehabilitation with PPP or TB was not performed on any patient. As with group 1, no differences in complications were observed between patients in this group. However, it is striking that in this group 2 with added SCC there was a statistical significance in reference to the transverse diameters of the hernia defect, which were lower in the cases of MIS, with a mean of 5.9 (SD: 2. 1) cm, almost half of the average associated with the open technique. Furthermore, in this group 2 (as in group 1) LIHs were treated in a significantly higher percentage using an MIS technique. The repair of an LIH using a sublay technique without adding an SCC is synonymous with the placement of a mesh in the preperitoneal space, without altering the normal anatomical relationships of the abdominal wall muscles.8,11 When an SCC is added to repair a LIH, the normal anatomical relationships of the abdominal wall muscles must necessarily be altered by using an open posterior SCC (TAR)10 or MIS.15 Why in the group with associated SCC, did patients with LIH and an MIS technique have a significantly smaller transverse diameter of the defect? Is MIS surgery of an LIH by altering the anatomy of the abdominal wall with an SCC justified in the case of defects with a mean of 5.9 cm? Furthermore, what is the reason why the mean transverse diameters of the defects of patients with a LIH and MIS technique were almost identical regardless of whether or not they associated an SCC? We do not have a clear explanation for these findings, although a necessary interpretation could be speculated about the possibility of overtreatment for patients who underwent lateral hernia surgery using an MIS technique with associated SCC.

Overtreatment has concerned surgeons for decades.26 Here we understand overtreatment as a medical intervention that is unlikely to add benefit to the patient and that is not aligned with the patient's values.27 Different strategies have been sought to prevent and avoid it, for example, second opinion programmes or clinical practice guidelines, among others.28 However, it seems that the focus of its prevention is currently cantered on the dialogue between surgeons and patients, that is, the practice of shared decision making, since overtreatment is not a reflection of rational reasoning. poor clinical practice, but is rooted in ineffective communication, misaligned expectations, and authoritarian paternalism.27 In theory, improving communication by presenting treatment options, understanding patients' values, and incorporating these into the surgeon-patient deliberation would reduce unnecessary surgery. However, we are aware that disease and treatment are composed of a series of events and interactions dispersed in time and place and distributed among a variety of individuals and organizations, and that surgical intervention is not the result of a specific moment’s deliberation.27 However, the practice and teaching of shared decision-making should be part of the updating of active surgeons and the training of future surgeons as another complement to “avoid” overtreatment.29,30 It is likely that only in this way can we answer which MIS techniques have a “clinically significant benefit” in abdominal wall surgery with a perceptible, but above all valuable effect for our patients.31

The limitations of our study are: first, the analysis is based exclusively on the EVEREG database, from which data could not be extracted from all the patients included in it. Second, EVEREG may not represent the global trends of Spain, since it does not cover all hospitals in the country, and this may determine biases in the types of patients, depending on the type of hospital and the treatments they apply. Third, the inherent heterogeneity of the patients included in a registry. Fourth, the small number of patients included in any of the analysis groups.

However, our work also has strengths: first, analysing all the patients included in the largest prospective database on IH available in Spain. Second, EVEREG itself confirms its usefulness for collecting prospective longitudinal data about different procedures such as IH. Third, the time elapsed since the inception of EVEREG is valuable to understand the trends of the different techniques. Fourth, the data have been collected independently of the research questions.

To sum up, this analysis of the EVEREG database points to a change in the techniques used in Spain, with the percentage of the open sublay technique (with and without associated SCC) increasing in the last six years in relation to the open onlay technique. The same occurs with the onlay MIS technique (IPOM), which has decreased in favour of sublay MIS techniques (with or without associated SCC). It seems that the quality of open surgery or MIS applying a sublay technique is good from the perspective of the low level of associated intra- and postoperative complications. However, the use of the MIS sublay technique with associated SCC for some type of hernia (IHL) may have represented overtreatment.

Conflict of interestsM. López-Cano has received fees for consulting, speaking, travel support, and participation in review activities from BD, Medtronic, and Gore. The rest of the authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: López-Cano M, Verdaguer Tremolosa M, Hernández Granados P, Pereira JA, en representación de los miembros del registro EVEREG. Técnica sublay abierta vs. mínimamente invasiva en el tratamiento de la hernia incisional. ¿Hay riesgo de sobretratamiento? Análisis del registro EVEREG. Cir Esp. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2023.02.006