Major emergencies or disasters pose great challenges to society and especially to all emergency services. In the last decades, the Mental Health perspective has been incorporated as an important part of comprehensive health care for those affected. Thus, the conceptual change from “multiple casualty incident” (MCI) to “multiple affected incident” (MAI) focuses on the care and well-being of all people affected by an incident, not only those who have suffered physical injuries. The objective of this article is focused on finding out the possibilities of intervention with patients labelled in triage as psychological green (without affectation and/or physical injuries), based on advanced psychological intervention in emergencies (IPA). The IPA, beyond removing those affected from danger, seeks to increase their sense of control and efficacy, both to face the situation and to increase their sense of competence in the experience of subsequent trauma with respect to that experience. In this sense, recent assessment possibilities, as well as psychological first aid approaches, allow new intervention applications in emergencies such as those made possible by remote air support (drones). Its application and possibilities as future options are discussed.

Las grandes emergencias o desastres plantean grandes retos a la sociedad y en especial a todos los servicios de emergencia. En las últimas décadas, se ha incorporado la perspectiva de la Salud Mental como una parte importante de la atención sanitaria integral a los afectados. Así, el cambio conceptual de “incidente de múltiples víctimas” (IMV) a “incidente de múltiples afectados” (IMA) se centra en la atención y bienestar de todas las personas afectadas por un incidente, no sólo en aquellos que han sufrido lesiones físicas. El objetivo del presente artículo se centra en conocer las posibilidades de intervención con afectados etiquetados en triaje como verdes psicológicos (sin afectación y/o lesiones físicas), a partir de la intervención psicológica avanzada en emergencias (IPA). La IPA, más allá de alejar a los afectados del peligro, persigue aumentar su sensación de control y eficacia, tanto para afrontar la situación como para aumentar su sentido de competencia en la vivencia de trauma posterior respecto a esa experiencia. En este sentido, las posibilidades recientes de evaluación, así como los enfoques de primeros auxilios psicológicos, permiten nuevas aplicaciones de intervención en emergencias como las que posibilitan los soportes aéreos remotos (drones). Se discute su aplicación y posibilidades como opciones de futuro.

Major emergencies or disasters, whether natural, technological, accidental, or events of intentional human design, such as terrorism, are incidents that can affect a huge number of people and the community as a whole. In general, these incidents pose great challenges to society and especially to all emergency services that may see their response capacity exceeded and must mobilise in a coordinated manner in order to rescue and preserve the survival of those affected, reducing mortality. and/or lessening the effects of the incident1,2 with the ultimate goal of reorienting the crisis towards rehabilitation.

On a historical level, it was after the terrorist attacks on the twin towers (11-S) in 2001 and the chain of attacks that took place in Europe in the following years in various cities such as Madrid, Beslan, Paris, London and Barcelona, that the perspective of mental health was incorporated as an important part of comprehensive health care for those affected. Understanding “affected” from a broad vision3 as a person who is immersed in a tragedy that causes a physical, psychological and/or social impact.

The conceptual change from “multiple victim incident” (MVI) to “multiple affected incident” (MAI) is part of a broader approach to emergency care that focuses on the care and well-being of all people affected by an event, not just those who have suffered physical injuries. The term “victim” has traditionally been used to describe people who have been injured or harmed in an incident, but does not recognise people who may have experienced psychological or emotional trauma as a result of the event. In addition, the term can convey a feeling of passivity and lack of control, which does not reflect the real response capacity of people, their level of resilience and their own resources to deal effectively with emergency situations.4,5

The term “affected” is more inclusive and recognises all people who have been impacted by an incident, including those who have suffered injuries, as well as their family, friends and the community in general. This conceptual change recognises, on the one hand, the importance of providing emotional and psychological support to all people affected by an event, and not just those who have suffered physical injuries. On the other hand, it admits that in the same way as there is a great variability in the type and magnitude of an MAI, there is also a great variability in terms of the different levels of how much people are affected: directly affected, indirectly affected, affected by intervening and affecting the community.3 Likewise, the scientific bibliography6 seems to indicate that there is a great variability in the effects of traumatic stress and other mental disorders in those affected by a MAI or major tragedy, and this variability ranges between 15% and 30%. The highest prevalence occurs above all in intentional MAI or human design (terrorism, caused accidents, etc.)

The objective of this article is focused on finding out the possibilities of intervention with patients labelled in a triage as psychologically green (without affectation and/or physical injuries) and who do not need to be evacuated to a health centre.

The need for a coordinated response by emergency operators in a MAIThe coordination of the main emergency operators and specialists involved in an MAI who are the rescuers, fire-fighters, health workers, civil protection, forensic doctors, etc., is key to guaranteeing a fast, effective and safe response to an emergency. When an event occurs with multiple victims, the security forces are in charge of cordoning off the area and securing the perimeter to facilitate access by rescue and health services. The rescuers (fire teams) are in charge of entering the hot zone (impact zone), making the first START7 selection and extracting those affected to the healthcare area. The emergency medical systems (EMS) in the cold zone (Health Area) carry out the META selection (Spanish/Extrahospital Triage Model8) and organise evacuation to health centres according to the classification of injury involvement. Civil protection technicians are in charge of receiving those affected and organising family centres (FCs). Other specialists such as forensic doctors will have a fundamental task in the process of identifying corpses, etc.

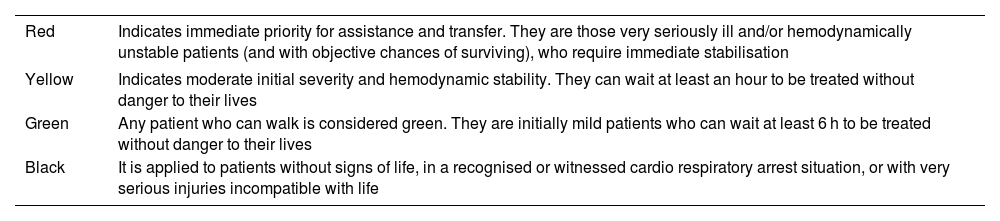

Triaje is the act of grouping victims into homogeneous categories to ensure the best performance of the available means in order to be able to carry out the necessary care for each person without delay and place them in optimal evacuation conditions. It is a system of classification of victims by colours that is used by consensus worldwide (see Table 1).

Colour code accepted by the Chicago Convention (1970).

| Red | Indicates immediate priority for assistance and transfer. They are those very seriously ill and/or hemodynamically unstable patients (and with objective chances of surviving), who require immediate stabilisation |

|---|---|

| Yellow | Indicates moderate initial severity and hemodynamic stability. They can wait at least an hour to be treated without danger to their lives |

| Green | Any patient who can walk is considered green. They are initially mild patients who can wait at least 6 h to be treated without danger to their lives |

| Black | It is applied to patients without signs of life, in a recognised or witnessed cardio respiratory arrest situation, or with very serious injuries incompatible with life |

The responses that we generate to stress are common to all people, it is our brain's reaction to the experience and/or perception of threat, and it is a totally adaptive process. These reactions tend to be more intense in intentional acts and incidents where aggression or acts of violence occur. Some of the elements of this type of incident that allow us to understand its greater intensity are the malevolence of the act itself - that they are caused by another person, with the feeling of betrayal that this entails; the injustice regarding what happened and the sense of immorality as it is an act against the established norms.9

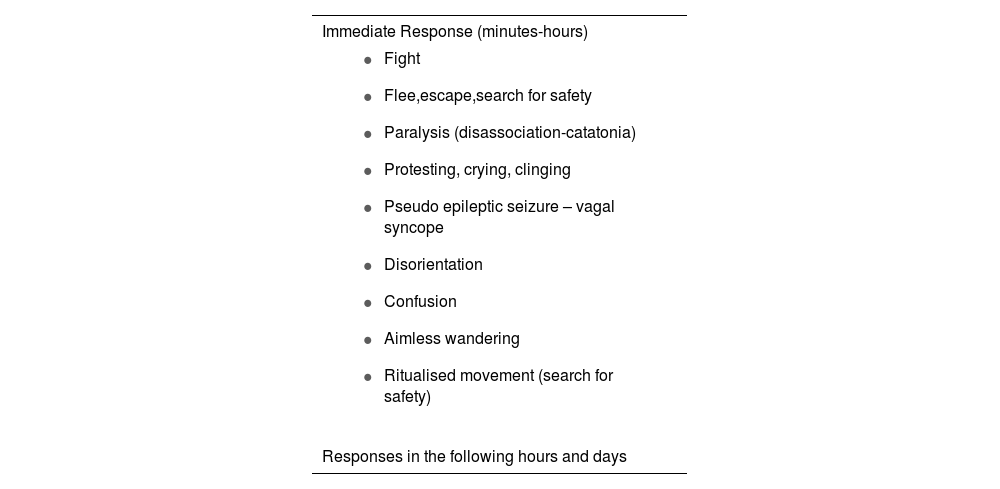

The first stress response to serious events is known as the acute stress reaction, they are the first attempts (conscious or unconscious) of the person to survive or face danger. It is also known as survival response,10 always dealing with normal responses and not as a psychopathological symptom. At a functional level, it encompasses responses in all spheres of human behaviour, physiological, emotional, cognitive, and behavioural (see Table 2).

Adapted from Johnstone and Boyle (2018).11

| Immediate Response (minutes-hours) |

|---|

|

| Responses in the following hours and days |

Behavioural

| Emotional

|

Physical

| Cognitive

|

The impact of disasters on the general population and on the psychological problems of victims has received much research attention.6,12 However, studies have focused on finding out what the psychological impact was on the victims after the event, instead of finding out what their response was during the first few hours, much less on how to intervene at a psychological level in the context of a MAI.

Secondary trauma in those who are interveningAn element to take into account in the population affected by a MAI are the participants and the effects on mental health. Recent studies highlight negative psychological implications in the professionals who are directly involved in the rescue,13 which frequently turns these health professionals into hidden victims of the disasters.14

We refer here to secondary trauma, due to working in risk situations and being exposed to people who have been traumatised or to the negative repercussions of incidents and disasters.15 According to the MAI typology, in cases of risk from Nuclear, Radiological, Bactereological and Chemical (NRVC) incidents, for example, this could involve personal fear when intervening. In addition to this fear would be the impact produced by the fact of “not being able to care for those affected” due to the risk of infection or death. In the case of terrorist incidents, it would be when the incident is active (non-neutralisation of the risk) and one must intervene with fear. This would also apply to the most recent and greatest psychological event for humanity: the effect of COVID-19.

Advanced psychological intervention in MAIThe 1970s and 1980s saw the shift from medical transport alone to on-scene care (pre-hospital care). This event led to the appearance of advanced life support units (ALSU) at the scene of the incident.16 All this was made possible by technological advances. With this evolution it was recognised that time was a critical factor in survival and that early medical attention could significantly improve the chances of recovery of those affected, making a difference to the lives of patients in critical situations.

Similarly, advanced psychological intervention (API), due to advances in neuroscience, stress and trauma in recent years, is leading to a paradigm shift in terms of early psychological intervention not only in ordinary out-of-hospital emergencies but also in the MAIs. An intervention that is physically closest in space and time, and within the window of opportunity (before 6 h), allows a restructuring of the memory before the consolidation of traumatic memories,17 and the possibility of reducing symptoms associated with the event, such as the decrease in the acute stress response (ASR), which is a clear precursor of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Despite the fact that there is little evidence that advanced psychological intervention can prevent PTSD, recent studies show a hopeful outlook in this regard.18,19

Advanced psychological intervention in emergencies (API) with those affected classified as psychologically green, that is, those affected without apparent physical injuries, is considered a second-order intervention that begins after the impact phase, once the risk situation is controlled and there is an environment of physical security, outside the impact area or adjacent areas of potential danger. In this regard, the classical terminology speaks of unharmed,20 referring to the medical report, but this concept is inappropriate because they are affected and it is therefore right to speak of those affected without apparent physical injuries or affected at a psychological level. However, it often happens that those labelled as green end up receiving care very late because they do not present with injuries or do not need medical attention a priori, and many leave the scene just by walking away.

The API in this phase goes one step further than “safety” meaning being away from danger, since safety is not just that. The feeling of security is a complex concept that depends on multiple variables (objective and subjective). For example, a person may feel insecure in a place where there are no imminent physical dangers, but where they perceive a lack of social support, a sense of threat or a lack of resources to deal with unforeseen situations. This feeling is also influenced by whether the person perceives that there are adequate protection measures, there is good communication, and a feeling of support from the people present and/or emergency responders.

In this sense, what characterises the experience of trauma in those affected has to do with how they have perceived the experience and, above all, how they have evaluated themselves, at the level of being ineffective or having remained passive. This assessment is tremendously important at the level of psychological health, and can have an enormous influence on the process of overcoming or on the subsequent impact of the experience on people's lives.

The API, therefore, strengthens the individual's own capacities and resources when facing the situation (“do not do anything that the affected people can do for themselves”); offers accompaniment and support (“you are not alone”, “the danger has passed”); helps in emotional self-regulation and the provision of information, and increases the feeling of control and efficacy, thereby generating a feeling of capacity (and not helplessness) which is a key psychological factor of resilience. In short, it is a question of directing the intervention to generate a feeling of security, control, strength and dignity as soon as possible.

Psychological first aid versus advanced psychological interventionThe API shares a purpose with psychological first aid (PFA),21 with the difference lying in the psychological need of those affected and the degree of professional specialisation required to meet those needs. The PFAs focus on 5 intervention principles:21 promoting a sense of safety, calm, self-efficacy, connection (natural and community support network) and generating positive expectations. PFA can be administered by those affected during an PTS episode, such as MAI (help between peers, in the case at hand, psychological “greens”) and by paraprofessionals or volunteers who have received basic training (2 h) and whose intervention is brief; provide immediate assistance (‘immediate responders’).22,23 The objective of PFAs is to provide emotional support and immediate practical assistance to those affected by a PTSD and who present emotional distress.24 In a MAI those affected labelled as green, who walk and obey orders, can leave the place of danger and enter a security zone, they usually only receive this indication and nothing else. This is necessary but insufficient, since they may remain for long periods of time in a distant place until they are transferred to a care area outside the incident (safe area). This encourages passivity, fatigue, and defencelessness, which can lead to psychological vulnerability and emotional discomfort.

To this we must add that in certain MAI, due to their magnitude and the time elapsing until professional help arrives, it is possible that the capacity of the security and emergency teams is insufficient to respond to the incident, and the more people able to help, the better for all those affected, as we pointed out previously. PDA can be appropriate during the initial time period here, when they are applied by non-specialised personnel.22

Both PFA and API share objectives. These consist in offering help and emotional support to those affected by a MAI. It is an aid aimed at generating a feeling of security, control, strength and dignity as soon as possible. The API, unlike the PFA, requires a more intensive use of human resources. It is applied by professionals and requires specialised training of more than 2 h, since it is a more intensive and lasting intervention (more than 2 h).23 The API is applied in a safe place after the end of the PTS when the person is no longer exposed to the situation and has acute stress reactions. Acute stress reactions after exposure to PTS, as previously mentioned (Table 2), manifest with great variability of responses in people and through a wide range of emotional, cognitive, behavioural, and somatic symptoms. The intensity and duration of these reactions are indicators or risk factors of developing traumatic stress (PTSD) in the future.

In order to discriminate those affected by a MAI who require specialised intervention (API), a selection must be made by the specialists to identify the people who are at greater risk, giving them the intervention priority. This task must be carried out by qualified professionals with experience in emergencies.

The assumptions of the triage of affected people where an API is indicated are (expanded from indications of the World Health Organisation & UNHCR23 guide):

- When there is persistent and intense subjective suffering in those affected that does not diminish during the first few hours, derived from negative thoughts and feelings, feelings of guilt and/or shame.

- When there are persistent hyperventilation crises and/or physiological hyperactivation (elevated heart rate, high blood pressure and low oxygen saturation, etc.), which do not diminish after the first hour following exposure to PTS after receiving PFA.

- When a state of confusion, disorientation and sensory-motor dissociation occurs.

- When there is paralysis or tonic immobility (temporary state of motor immobility in response to a situation of extreme fear).

- Intrusions are presented in the form of disturbing thoughts and/or images (flashbacks) of the incident experienced directly and/or witnessed.

- Faced with states of agitation and aggressiveness (verbal/non-verbal).

- With vulnerable population (history of mental disorder, elderly people, minors, people with physical, sensory or intellectual disabilities).

For all these reasons, advanced psychological intervention requires specialisation,23 at a theoretical-practical level in evidence-based therapy and techniques: trauma-based cognitive behavioural therapy,23,25 desensitisation and reprocessing by eye movements (EMDR),23,26 memory structuring (in trauma) and vagal breathing,27 as well as other approaches such as verbal de-escalation techniques, vagal psychophysiological deactivation techniques, crisis communication, etc.

Overall safety: physical, psychological, social and judicialComprehensive early intervention results in “safety” at a physical level (saving lives), psychological (preventing trauma) and in some way a “legal” security and a “social” security are also necessary due to the impact that the event can have on assets such as the home or the business, and also because there may be a desire to continue working and/or subsist at the family level. When developing these aspects of global “security” it can sometimes be complex that they are all guaranteed equally. Take, for example, the case of Las Ramblas in Barcelona on August 17, 2017 (Intentional Multiple Victim Incident, IMVi). Legal certainty for those affected by a terrorist act would be to obtain recognition of the “status of victim of terrorism” (with rights to receive legal, psychological help…). The case of the attack on Las Ramblas led to serious problems in relation to the identification of those affected, both directly and indirectly, due to the very characteristics of the event, the complexity and the lack of procedures for major emergencies that contemplate the broader vision of “affected” as including not just physically affected victims. There were many people who fled the scene, who walked on their own, who remained confined for hours in premises, homes, hotels near Las Ramblas, etc., given that the incident was active and it had not been possible to neutralise or eliminate the threat. Most of these “affected” peoples could not be identified in the care centres that the emergency services set up. Many of these people over time presented sequelae (phobias, agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress disorders, anxiety, depression, etc.). We must not forget that acute stress disorder is diagnosed in the first 30 days and post-traumatic stress disorder after 30 days. The difficulty in establishing affiliation or initial assistance or in the first days for many of them entailed an added difficulty for them to be recognised as “victims of terrorism” and therefore access resources and attention, both health and social or legal.

Future challenges in the psychological approach to a MAIThe first great challenge for the future is to provide early comprehensive health care (physical and psychological) in emergencies and in MAI, so that psychological-emotional care is included in the procedures and protocols of agencies and emergency operators. For this, it is necessary to have a theoretical evidence-based corpus of the best practices in emergency psychology and a homogenisation of the specialised training required of professionals. To build a solid theoretical and empirical background, cooperation is required between administrations, emergency operators, universities, etc., through lines of research that support the preventive value of traumatic stress and other mental disorders through early intervention.

Furthermore, it is necessary to take advantage of technological and digital advances applied to health in the field of emergencies and MAI (applications that allow better management of those affected at different levels of assistance, trauma self-assessment applications…).

A novel approach in MAI that different national and international organisations are implementing, for better incident management and to facilitate medical triage, is the use of remote air support units (drones).28 The use of this support for the different operators can be key to starting early care right at the beginning, before the emergency teams can arrive, as well as in scenarios that are difficult to access or where the risk or threat persists, to carry out a health reselection and even in support of those affected labelled as psychologically green.

Drones are a collaborative tool, with time-dependent effectiveness, useful for all parties involved (security, rescue, health and logistics) involved in the response to MAI and/or Intentional Multiple Casualty Incidents (IMVi). It is a very powerful real-time source of value that facilitates the Health Area (HA), previously known as Advanced Medical Post (AMP) and the Advanced Command Centre (ACC) to optimise a strategic response by reducing decision-making times (operational intelligence). As described, through the use of the voice-on-board drones, it would be possible, even before the arrival of the first professional responders to the place of the emergency, for lay responders (themselves in situ victims) to initiate healthcare acts under direct distance supervision from a healthcare professional.

The drones provide support (logistical support and protection to the interveners and the victims) throughout the assistance by monitoring the evolution of the incident, and checking the appearance of possible added risks. Thus, the location of all groups of interveners is known at all times and it will be possible to notify them, thanks to the use of the on-board loudspeaker. In the case of any added danger, it will be possible to change the affected area according to the intervention requirements, to immediately reveal if further means of support are on their way and where they can be placed safely. Likewise, during the first few moments, the use of remote air support technologies (drones) can be used to send messages and instructions to large groups to move to a safe area, or receive messages on how to do psychological first aid with slogans, such as: “Ask the person next to you their name, if they know where they are…”, if the person does not respond (dissociated), give instructions to stay by their side until help arrives, convey messages that help is on the way, etc.

Despite the great potential of the use of drones within the field of health emergencies, and specifically, within IMVi, their use in Spain is practically anecdotal.

ConclusionThe conceptual change from “multiple victim incident” (MVI) to “multiple affected incident” (MAI) is part of a broader approach to emergency care that recognises the importance of providing emotional and psychological support to all people affected by an event, and not only to those who have suffered physical injuries, admitting that there is great variability in the different levels of affectation in people.

The possibility of intervening in the emotional and psychological area, especially with those affected classified as psychologically green, is a great opportunity and an important evolution in the management of MAI. In this sense, there are 2 types of possible approaches, the psychological first aid (PFA) approaches and the advanced psychological intervention (API). Both share the purpose of guiding the person to generate a feeling of security, control, strength and dignity as soon as possible, differing in the need for intervention of those affected at a psychological level (severity and intensity of discomfort) and the degree of professional specialisation required to face these needs (being able to apply the PFA both by those themselves affected during a PTS incident following simple orders, as well as by paraprofessionals or volunteers, up to the intervention in API by specialised psychologists).

Providing comprehensive health care (physical and psychological) early in emergencies and specifically in a MAI is not only in keeping the available scientific evidence, but also represents an innovative and future intervention in the context of MAI.

FundingThis research did not receive specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Please cite this article as: Cuartero A, Pérez-González A. Hacia un cambio de paradigma en la atención psicológica en grandes emergencias: de incidentes con múltiples víctimas a incidentes con múltiples afectados. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reml.2023.07.001.