Approximately 3500 people commit suicide every year in Spain. The main aim of this study is to explore if a spatial and temporal clustering of suicide exists in the region of Antequera (Málaga, España).

MethodsSample and procedure. All suicides from January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2008 were identified using data from the Forensic Pathology Department of the Institute of Legal Medicine, Málaga (España).

Geolocalisation. Google Earth was used to calculate the coordinates for each suicide decedent's address.

Statistical analysis. A spatiotemporal permutation scan statistic and the Ripley's K function were used to explore spatiotemporal clustering. Pearson's chi-squared was used to determine whether there were differences between suicides inside and outside the spatiotemporal clusters.

ResultsA total of 120 individuals committed suicide within the region of Antequera, of which 96 (80%) were included in our analyses. Statistically significant evidence for seven spatiotemporal suicide clusters emerged within critical limits for the 0–2.5km distance and for the first and second semanas (p<0.05 in both cases) after suicide. There was not a single subject diagnosed with a current psychotic disorder, among suicides within clusters, whereas outside clusters, 20% had this diagnosis (χ2=4.13; df=1; p<0.05).

ConclusionsThere are spatiotemporal suicide clusters in the area surrounding Antequera. Patients diagnosed with current psychotic disorder are less likely to be influenced by the factors explaining suicide clustering.

En España, cada año consuman suicidio alrededor de 3.500 personas. El principal objetivo del presente estudio fue examinar si eran evidentes agrupaciones (clusters) espacio-temporales de suicidio en la región de Antequera (Málaga, España).

MétodosMuestra y procedimiento. Entre el 1 de enero de 2004 y el 31 de diciembre de 2008, se identificaron todos los casos de suicidio consumado (fuente: Servicio de Patología Forense del Instituto de Medicina Legal, Málaga, España).

Geolocalización. Usamos Google Earth para calcular las coordenadas del domicilio de todos los casos de suicidio.

Análisis estadístico. Usamos el programa SaTScan® espacio-temporal y la función K de Ripley para examinar la presencia de agrupaciones (clusters) espacio-temporales de los casos de suicidio. Acto seguido, utilizamos la prueba de la χ2 de Pearson para determinar la presencia de diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre los casos de suicidio identificados dentro y fuera de las agrupaciones de suicidio.

ResultadosEn los análisis del presente estudio efectuado en el municipio de Antequera, de un total de 120 individuos que cometieron suicidio se incluyeron 96 (80%). Se identificaron pruebas estadísticamente significativas para 7 agrupaciones espacio-temporales de suicidio dentro de los límites críticos de 0–2,5km de distancia y durante la primera y segunda semana después del caso de suicidio (p<0,05 en ambos casos). Entre los casos de suicidio dentro de agrupaciones (n=17), no hubo ningún individuo en el que se hubiera establecido un diagnóstico de trastorno psicótico actual, mientras que, entre los casos de suicidio fuera de las agrupaciones espacio-temporales, en el 20%, se había establecido dicho diagnóstico (χ2=4,13; gl=1; p<0,05).

ConclusionesEn la región circundante de Antequera están presentes agrupaciones (clusters) espacio-temporales de los casos de suicidio. Entre pacientes con un diagnóstico de trastorno psicótico actual hubo menos probabilidades de una influencia por los factores que determinan las agrupaciones espacio-temporales de los casos de suicidio consumado.

Early detection of disease outbreaks is a difficult task.1 Although, from time immemorial to the 20th century, suicide outbreaks have been reported in different populations,2 empirical results remain contradictory.3 A suicide cluster means the presence of an unusually high number of geographically localized and/or temporally localized suicide cases unrelated to chance.2 Due to the weakness of classical studies performed on suicide clusters, implementing statistical methods generally used for detecting infectious disease clusters was an important contribution to this field.4 Indeed, spatiotemporal scan analyses are an appropriate solution for early detection of disease outbreaks.2 These methods can be used to find clusters showing a higher disease frequency within a predetermined spatiotemporal setting. They have been used for various diseases1; however, evidence of their use in suicide cases is limited.5 Implementing these new analytical tools could help reduce morbidity and mortality of suicide impact, because it would improve early detection of suicide clusters.

Suicide clusters represent about 5–10% of suicide cases, and this phenomenon seems to be particularly prevalent among adolescents and young adults.2,4,6–8 Compared to the similar suicide “contagion” concept, which pays attention to the reasons that underlie the accumulation of cases (accounting for the why of the cluster in suicide cases), the cluster concept disregards the underlying reasons for case accumulation.9 This distinction is important, because although suicide case contagion is often considered the only mechanism behind suicide clusters, and the analogy between the “model of infectious diseases” and suicide clusters is convincing,4 suicide clusters include imitation, and may also involve other mechanisms. For example, in a recent study conducted in Scotland on spatial suicide clustering, the authors examined mass suicide cluster events in 10,058 relatively small areas during three time periods: 1980–1982, 1990–1992 and 1999–2001. They found three clusters not explained by contagion, but due to socioeconomic deprivation concentration.3

At least two major factors have hampered research on suicide clusters: first, the lack of standardized suicide cluster definition in terms of the number of “required” suicide cases, and spatiotemporal limitations that restrict comparability between various research4,10–12; second, although the spatiotemporal methods were an appropriate alternative for the suicide cluster study, some limitations have probably prevented study generalization. Essentially, there are two types of spatiotemporal clustering methods10: (1) pairing methods, based on calculating the distance between observation pairs, and (2) cell methods, which subdivide the geographical area and study time into spatiotemporal units into which cases are distributed. In general, the Knox procedure13 is the most used pairing method. It considers all possible pairs of cases and spatiotemporal distances between them. For each pair, it attempts to establish a cluster showing a positive relationship between spatiotemporal distances.2 If some cases are close in space, they are also close in time, or on the contrary, there is evidence of spatiotemporal clustering. Unfortunately, the Knox method has some disadvantages limiting its use to detect suicide clusters (see the Methods section below).

Based on published studies, we examined whether in the town of Antequera (Malaga, southern Spain) spatiotemporal suicide clusters occurred. We included the classic suicide cluster definition suggested by Gould−a series spatiotemporal localized suicide cases2−and to identify clusters, we used Ripley's K function,14 a non-parametric statistical tool of widespread use in medicine.15 Within the municipality of Antequera, we expected to find several space (0–2.5km) and time (1 or 2 weeks) clusters. Furthermore, we hypothesized that personality disorders would be more likely to appear within suicide clusters than outside them.

MethodsPopulation and methodIn the municipality of Antequera, from January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2008, using data from the Forensic Pathology Department of the Institute of Legal Medicine in Malaga, Spain, all suicide cases were identified, defined as any death with cause of death corresponding to codes E950–959 of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). In the town of Antequera during the 5-year period in which this study was undertaken, we estimated a median of 112,410 inhabitants (Institute of Statistics of Andalusia, 2011); the municipality includes the following towns: Alameda, Almargén, Antequera, Campillos, Cañete la Real, Fuente de Piedra, Humilladero, Mollina, Sierra de Yegüas, Teba and Valle de Abdalajís. We selected this region due to its high suicide rates (see Results section), and because an update of published studies revealed that rural areas are at greater risk of suicide clusters. The corresponding research committee approved the study.

We followed published procedures for psychological autopsies.16 After a suicide event occurred in the study area, we obtained a family member's informed consent. All interviews were held at 3–18 months after the event.

Using the DSM-IV version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)17 and the Spanish version of the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS)18, respectively, disorder diagnoses were established for axis I and axis II in the suicide cases. The MINI is a brief and easy to administer structured diagnostic interview that assesses axis17 DSM-IV disorders.

The DIGS was designed to assess major psychiatric disorders and personality disorders.18 It is a common assessment tool for genetic studies. To assess acute life events in the month prior to suicide, we used the St. Paul Ramsey Life Experience Scale.19

GeolocationWe used Google Earth (http://www.google.es/intl/es/earth/index.html) to determine each suicide decedent's address coordinates. Later, we projected them on a map using a WGS84 ellipsoid model with a GEO v9.200712 Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinate Converter. After suicide rate calculation including the 120 suicides, 24 suicide cases were excluded from the remaining analyses, because the suicide decedent's address was unavailable.

Statistical analysisCluster analysis using the spatiotemporal SaTScan® programWe used the spatiotemporal permutation model to retrospectively examine spatiotemporal clusters by variations/modifications of different amplitude spatiotemporal windows and assess their influence on model results. Initially, this program was designed to detect temporal clusters.20 However, it was implemented shortly after in the context of space clusters.10 This type of analysis does not require data from the population at risk; therefore, it is useful for detecting disease outbreaks when the only data available is the number of cases.1 In essence, the SaTScan® spatiotemporal permutation program is based on creating cylinders that track the entire area and study period, overlapping to define a “scan window” with a predetermined time period in a given area. Each cylinder presents a potential outbreak (i.e., in this study, a suicide case cluster). The circular cylinder base represents the possible outbreak geographic area, and the cylinder's height is the time period (duration). The SaTScan® spatiotemporal permutation program iterates all possible combinations among various bases (space) and heights (time).1,7 Statistical significance is reached with the null hypothesis by calculating the probability of obtaining the maximum number of suicide cases in the predetermined “scan window” (i.e., it is expected that cases within each cluster follow a Poisson distribution with constant spatiotemporal risks). In other words, it was predictable that the total number of suicide cases would be distributed evenly on a preselected period of time.1,7 Therefore, by rejecting the null hypothesis, we assumed that the relative risks inside and outside the cylinder would be different. All detection analyses were performed with the SaTScan statistical software (http://www.satscan.org),21 which can be downloaded for free.

Ripley's K function was selected from various statistical methods to detect spatiotemporal disease clustering.14 This function, which is based on Monte Carlo simulations, is a generalization of the Knox method.13,14 This method has two major drawbacks: firstly, selection of spatiotemporal distances is subjective; and secondly, this method requires multiple tests.22 Ripley's K function is free of these limitations. Furthermore, unlike the Knox test, it can be used in relatively small geographic areas.23 Ripley's K function's spatiotemporal values were calculated with the Splancs statistical package24 using the R parameter (www.r-project.org).

Based on published studies, contingency tables were generated for 4-time period combinations (1–4 weeks) and 4 distances (0–2.5km; 2.5–5km; 5–10km; and 10–15km) considered as critical.7 A universally accepted definition of spatial limits for “suicide case clusters” is still unavailable; however, Gould et al.25 considered the municipality of residence as a more susceptible spatial unit than the town of residence. For Ripley's K function, the triggering event was defined as a clustering's 0–2.5km, and 0–1 and 0–2 week temporal–spatial confluence. For each of these spatiotemporal combinations, we determined the probability of observing a suicide cluster assuming a normal distribution (p<0.05), and using an iterative simulation process. In order to test spatiotemporal interaction, we developed a permutation test based on Ripley's K functions observed in this study population, using bootstrapping techniques. The contrast test was calculated as the median of differences in simulated spatiotemporal K functions, and the product of the estimated K functions in each of the spatiotemporal dimensions. To calculate the contrast test theoretical distribution at each scale, a total of 1000 simulations were performed.

Descriptive analysisWe used the Pearson χ2 test (2-tailed) to examine whether there were significant differences among suicide cases (inside compared to outside clusters) in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and method employed to commit it. For these analyses, we used the Macintosh-based SPSS v.20 software.

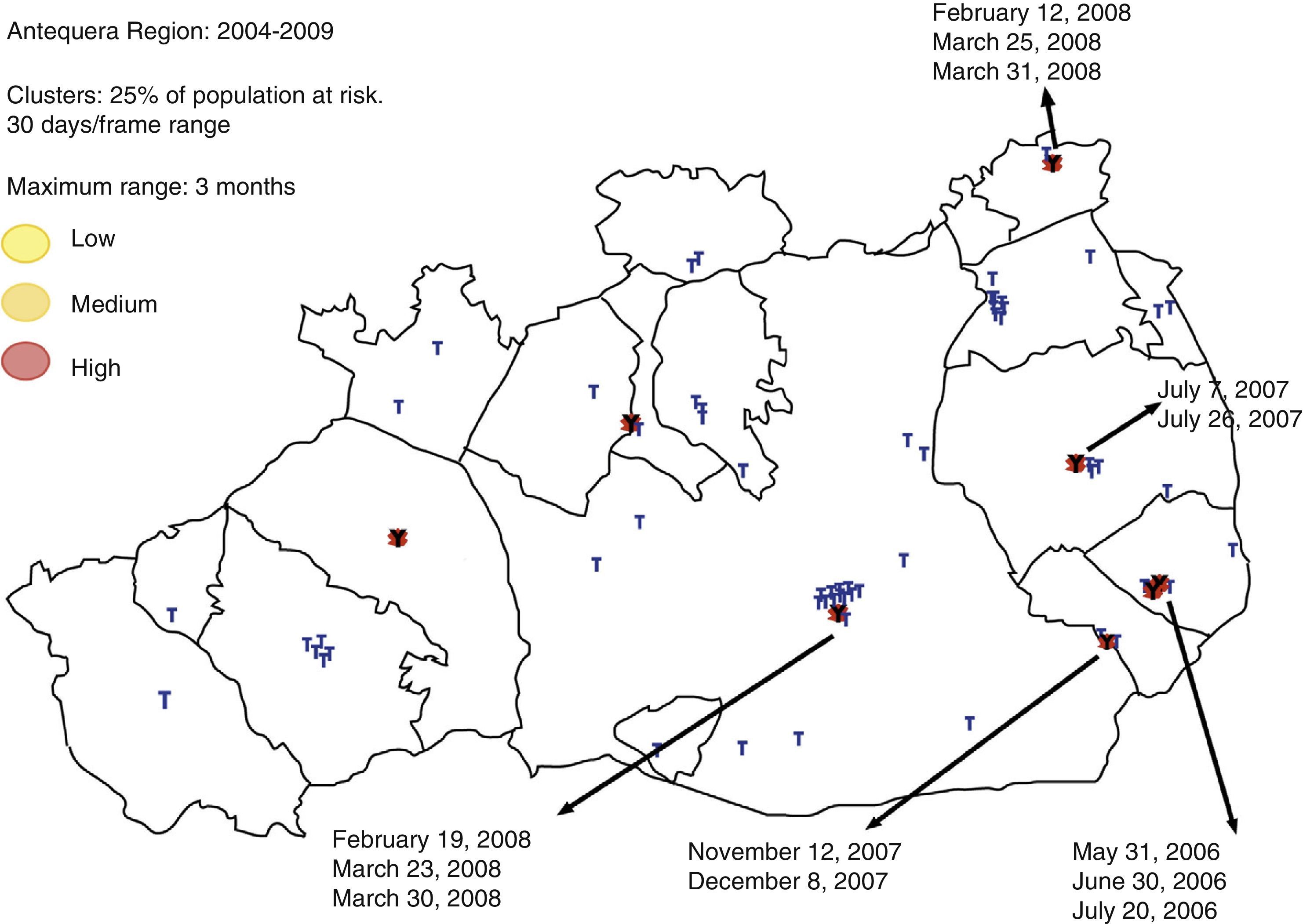

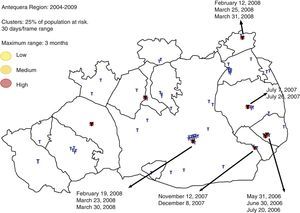

ResultsIn Antequera, between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2008, a total of 120 individuals committed suicide. For the 2004–2008 period in Antequera, the average annual suicide rate (adjusted for age) was 24/100,000 (20/100,000–40/100,000 inhabitants; 95% confidence interval [CI]). The graph of Fig. 1 shows the various spatiotemporal clusters (n=7) found in the Antequera region using the SaTScan® program. In this region, significant spatiotemporal clusters were observed (p<0.05) for areas in this region and geographically dispersed for others.

Graphical representation of major spatiotemporal clusters in the Antequera municipality, located in the northern area of Malaga, Spain. The seven red circles (marked with arrows) represent high spatiotemporal interaction. Each data point represents one suicide case in the spatiotemporal framework.

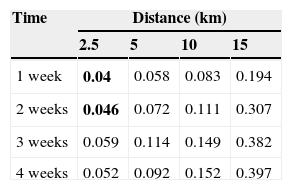

Table 1 shows spatiotemporal analysis results using week 1, 2, 3 and 4 windows. Statistically significant evidence of temporal–spatial clustering was observed in critical limits of 0–2.5km and first and second week (p<0.05 in both cases).

p Values for the spatiotemporal interaction after statistical analysis with Ripley's K function.

| Time | Distance (km) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | 5 | 10 | 15 | |

| 1 week | 0.04 | 0.058 | 0.083 | 0.194 |

| 2 weeks | 0.046 | 0.072 | 0.111 | 0.307 |

| 3 weeks | 0.059 | 0.114 | 0.149 | 0.382 |

| 4 weeks | 0.052 | 0.092 | 0.152 | 0.397 |

The time variable indicates the number of weeks after a second suicide case occurs following a suicide index-case, and the distance variable represents the number of kilometers between the second and third suicide case after a suicide index-case.

Statistically significant associations are shown in bold.

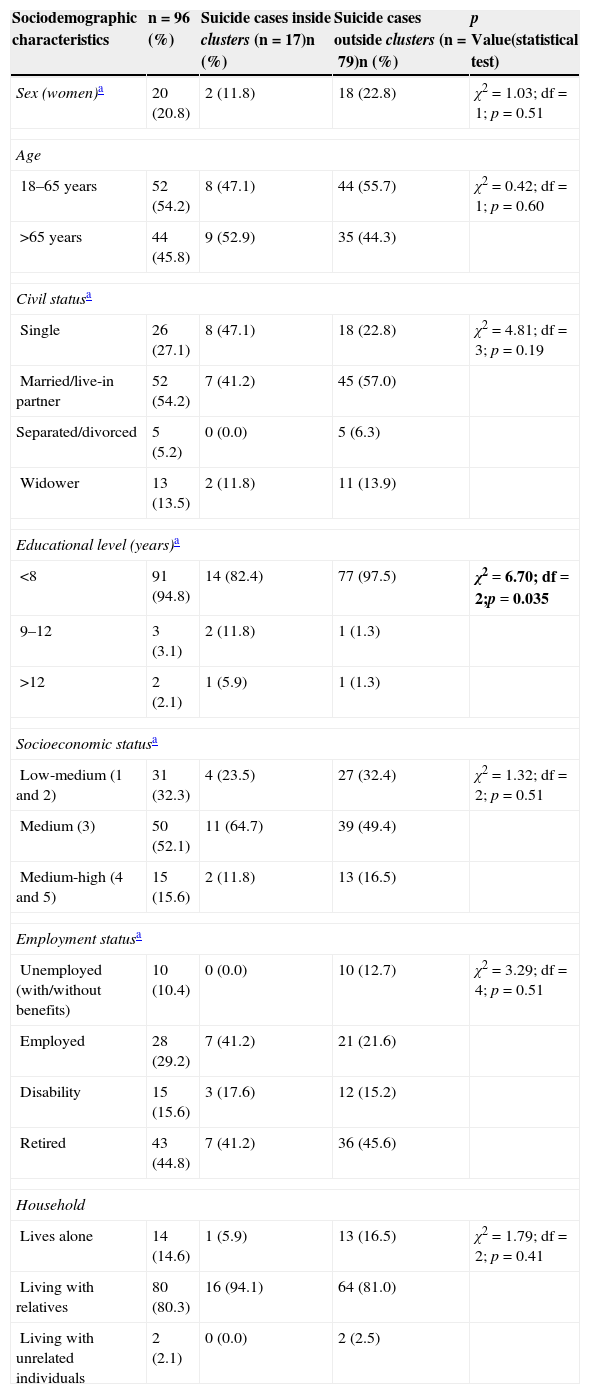

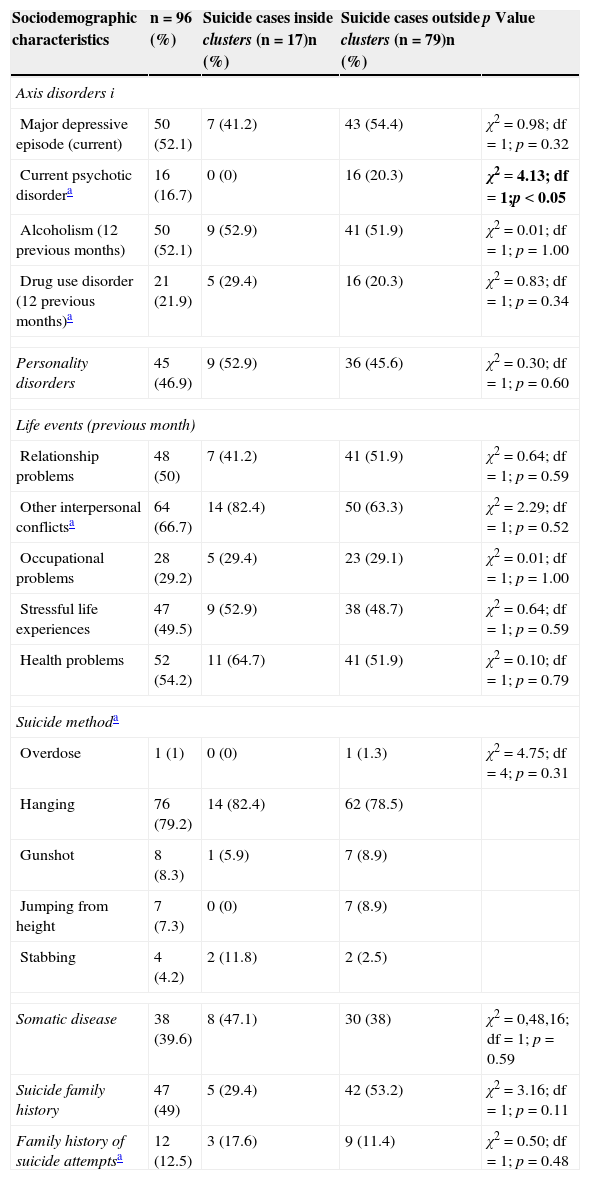

Then, we examined whether suicide cases included in spatiotemporal clusters were significantly different from cases outside them. Table 2 shows the sociodemographic characteristics for all suicide cases with available postal address (n=96; the address of the remaining 24 cases was unavailable, but this had no effect on sociodemographic and clinical variables, compared to other suicide cases). 79.2% of suicide cases were men. Median age for committed suicide cases was 54.1 (±20.3) years. Among suicide cases within clusters, the probability of cases with a higher level of education was higher than among suicide cases outside them (χ2=6.70; df=2; p=0.035). With respect to clinical characteristics (Table 3), among suicide cases within clusters, there were no cases with current psychotic disorder diagnosis, while outside clusters, 20% of suicide cases had this diagnosis (χ2=4.13; df=1; p<0.05). Finally, among suicide cases after the suicide index-case, 5 of 7 clusters had been diagnosed with a personality disorder.

Suicide characteristics in Antequera (Malaga, Spain), 2004–2008.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | n=96 (%) | Suicide cases inside clusters (n=17)n (%) | Suicide cases outside clusters (n=79)n (%) | p Value(statistical test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (women)a | 20 (20.8) | 2 (11.8) | 18 (22.8) | χ2=1.03; df=1; p=0.51 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–65 years | 52 (54.2) | 8 (47.1) | 44 (55.7) | χ2=0.42; df=1; p=0.60 |

| >65 years | 44 (45.8) | 9 (52.9) | 35 (44.3) | |

| Civil statusa | ||||

| Single | 26 (27.1) | 8 (47.1) | 18 (22.8) | χ2=4.81; df=3; p=0.19 |

| Married/live-in partner | 52 (54.2) | 7 (41.2) | 45 (57.0) | |

| Separated/divorced | 5 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (6.3) | |

| Widower | 13 (13.5) | 2 (11.8) | 11 (13.9) | |

| Educational level (years)a | ||||

| <8 | 91 (94.8) | 14 (82.4) | 77 (97.5) | χ2=6.70; df=2;p=0.035 |

| 9–12 | 3 (3.1) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (1.3) | |

| >12 | 2 (2.1) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Socioeconomic statusa | ||||

| Low-medium (1 and 2) | 31 (32.3) | 4 (23.5) | 27 (32.4) | χ2=1.32; df=2; p=0.51 |

| Medium (3) | 50 (52.1) | 11 (64.7) | 39 (49.4) | |

| Medium-high (4 and 5) | 15 (15.6) | 2 (11.8) | 13 (16.5) | |

| Employment statusa | ||||

| Unemployed (with/without benefits) | 10 (10.4) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (12.7) | χ2=3.29; df=4; p=0.51 |

| Employed | 28 (29.2) | 7 (41.2) | 21 (21.6) | |

| Disability | 15 (15.6) | 3 (17.6) | 12 (15.2) | |

| Retired | 43 (44.8) | 7 (41.2) | 36 (45.6) | |

| Household | ||||

| Lives alone | 14 (14.6) | 1 (5.9) | 13 (16.5) | χ2=1.79; df=2; p=0.41 |

| Living with relatives | 80 (80.3) | 16 (94.1) | 64 (81.0) | |

| Living with unrelated individuals | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.5) | |

df: degrees of freedom.

Statistically significant relationships are shown in bold.

Characteristics of clinical suicide cases in Antequera (Malaga, Spain), 2004–2008.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | n=96 (%) | Suicide cases inside clusters (n=17)n (%) | Suicide cases outside clusters (n=79)n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis disorders i | ||||

| Major depressive episode (current) | 50 (52.1) | 7 (41.2) | 43 (54.4) | χ2=0.98; df=1; p=0.32 |

| Current psychotic disordera | 16 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 16 (20.3) | χ2=4.13; df=1;p<0.05 |

| Alcoholism (12 previous months) | 50 (52.1) | 9 (52.9) | 41 (51.9) | χ2=0.01; df=1; p=1.00 |

| Drug use disorder (12 previous months)a | 21 (21.9) | 5 (29.4) | 16 (20.3) | χ2=0.83; df=1; p=0.34 |

| Personality disorders | 45 (46.9) | 9 (52.9) | 36 (45.6) | χ2=0.30; df=1; p=0.60 |

| Life events (previous month) | ||||

| Relationship problems | 48 (50) | 7 (41.2) | 41 (51.9) | χ2=0.64; df=1; p=0.59 |

| Other interpersonal conflictsa | 64 (66.7) | 14 (82.4) | 50 (63.3) | χ2=2.29; df=1; p=0.52 |

| Occupational problems | 28 (29.2) | 5 (29.4) | 23 (29.1) | χ2=0.01; df=1; p=1.00 |

| Stressful life experiences | 47 (49.5) | 9 (52.9) | 38 (48.7) | χ2=0.64; df=1; p=0.59 |

| Health problems | 52 (54.2) | 11 (64.7) | 41 (51.9) | χ2=0.10; df=1; p=0.79 |

| Suicide methoda | ||||

| Overdose | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | χ2=4.75; df=4; p=0.31 |

| Hanging | 76 (79.2) | 14 (82.4) | 62 (78.5) | |

| Gunshot | 8 (8.3) | 1 (5.9) | 7 (8.9) | |

| Jumping from height | 7 (7.3) | 0 (0) | 7 (8.9) | |

| Stabbing | 4 (4.2) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (2.5) | |

| Somatic disease | 38 (39.6) | 8 (47.1) | 30 (38) | χ2=0,48,16; df=1; p=0.59 |

| Suicide family history | 47 (49) | 5 (29.4) | 42 (53.2) | χ2=3.16; df=1; p=0.11 |

| Family history of suicide attemptsa | 12 (12.5) | 3 (17.6) | 9 (11.4) | χ2=0.50; df=1; p=0.48 |

df: degrees of freedom.

This study highlights evidence on the existence of spatiotemporal suicide case clusters in various areas of the Antequera region in Spain. Observed spatiotemporal interaction was limited geographically and chronologically to 2.5km and a 2-week interval. The number of spatiotemporal suicide clusters described in this study is included in the point clusters concept; these are suicide clusters contiguous in both time and space.8 Traditionally, direct social learning of same location individuals has explained this type of clusters, which have been considered to occur only in institutions. However, this study's findings show that suicide case point clusters can also occur in geographically isolated, relatively small areas, besides occurring in institutions.26 Furthermore, this study's results show that the SaTScan® spatiotemporal permutation program and Ripley's K function are useful tools for spatiotemporal suicide cluster analysis. Moreover, when we compared suicide cases inside and outside clusters, we found no major differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Every year in Spain, about 3500 individuals commit suicide (http://www.ine.es/). The suicide rate detected in the Antequera region (24/100,000 inhabitants) was higher than average suicide rate in Spain documented in 2008 (7.6/100,000 population; http://www.ine.es/). This elevated suicide rate coincides with the described high suicide rates in relatively small geographical areas in different populations around the world,3,6,7 and could be explained by the characteristics of this region. The Antequera community is a rural area measuring 2141.2km2 in Malaga (Andalusia, Spain).27 Suicide is more common in isolated rural areas.28,29 For individuals who live in rural areas, major risk factors for suicide are sociocultural (e.g., having an exhausting lifestyle and a lower rate of using mental health services), geographic and interpersonal isolation (e.g., loss of sense of community and limited availability of social and emotional support), as well as economic and social problems.29 Indeed, the Scottish government implemented a prevention strategy (“choose life”) in order to reduce suicide rates by 20% between 2003 and 2013. The only priority clusters defined by geographic region were “remote or isolated rural areas”.3

One possible explanation for this spatiotemporal cluster series in Antequera is contagion.30 Contagion can be explained by direct exposure if the individual actually knows the suicide index-case, or by indirect exposure (e.g., word-of-mouth or media delivered information).10,11,31 Direct exposure may exert its contagious effect through social learning, identification, or even imitation.11 In addition, word-of-mouth and media delivered information may be diffusion factors in relatively small geographic areas where direct relationships predominate. In general, suicide clusters have been documented among adolescents and young adults, particularly women.25,26,30 However, they have also been described in older populations, or even exclusively among men. For example, one study reported a suicide cluster case among 55- to 64-year-old individuals 1 week after the suicide index-case.25 Likewise, Bechtold31 studied a cluster of nine suicide cases involving adolescents and young adults among Arapahoe, also known as Gens-de-vache Native Americans in the Great Plains, USA (currently, Colorado and Wyoming). This community hosts multiple tribes and their total population amounts to several thousand individuals. The nine suicides were males of the same tribe who committed suicide within an 8-week period. Interestingly, all suicide cases were interrelated and had spread not only to individuals with risk factors, but also apparently healthy individuals with shared characteristics. The author suggested that for healthy individuals, imitation was the most important etiological factor explaining the spread of suicide. Other authors have also reported that imitation is more common among individuals sharing similar characteristics with the suicide victim.32,33

Contagion is but one of the mechanisms that could explain suicide clusters.6,8,9 Certainly, other factors can explain this study's findings, such as concurrent effects of some harmful influences (e.g., illness, life events and socio-economic problems). Joiner argued that suicide point clusters resulted from four coalescing factors among suicide victims: first, personal suicide risk factors (e.g., major depression); second, existence of negative precipitating life events; third, lack of social support; and fourth, tendency to build group relationships.9 Findings of this study reinforce this hypothesis empirically, as the only statistically significant result documented herein was that, among suicide cases within clusters, no individual was diagnosed with current psychotic disorder, while 20% of individuals outside clusters had this diagnosis. This could indicate that patients diagnosed with acute psychosis are less likely to be influenced by factors that explain suicide clustering. Another additional explanation for the contagion hypothesis is the newly described link between altitude and suicide.28

This study's results differ from Saman et al.5 and Exeter and Boyle3 studies’ findings in some respects. For example, the prevalent suicide method in our population was hanging, while in Kentucky5 it was firearms, and poisoning in Scotland.3 The reason could be cultural and regional “preferences” for suicide methods. The traditional method of choice in Spain is hanging.27 Furthermore, methods used to commit suicide inside and outside suicide clusters were not significantly different compared to those described in the two aforementioned studies. Moreover, contrary to what we expected, we failed to find that personality disorders were more likely to occur within suicide clusters. We based our hypothesis on the clinical perception that patients with personality disorders are easier to be influenced, and thus may reflect suicidal behavior of suicide index-cases. Interestingly, for most clusters, a large share of individuals committing suicide after the suicide index-case had been diagnosed with a personality disorder, which is consistent with our hypothesis. A recently published study also demonstrates that individuals with a personality disorder may be more prone to contagion processes.34

Post-prevention measures that can be implemented after a suicide index-case include: identification of individuals at risk (e.g., those with a history of a previous suicide attempt), identification of the most vulnerable individuals (i.e., individuals who share characteristics with the index case), and reduced emotional distress within the community.8,35 Current demonstration of spatiotemporal suicide clusters indicates that prevention guidelines must also include primary care professionals to supervise the most vulnerable individuals in the same location, at least during the first 2 weeks after the suicide index-case.8

Strengths and limitations of this studyThe primary strength of this study is the methodology used (Ripley's K function). This allowed us to dispense with the Bonferroni correction, which is usually too conservative for this type of analysis. Moreover, using new spatiotemporal techniques proved useful in detecting suicide cluster cases.

Some limitations must also be considered. For example, better spatial modeling strategies are available for this type of research questions (i.e., Bayesian spatial models). Yet, we believe that the analyses used are valid enough to answer these questions appropriately. Moreover, spatiotemporal permutation must only be conducted if the time period covered in the analysis is brief enough so that the underlying population at risk has not changed substantially during the period covered by the study. This study covers a 5-year period, which could have cast some doubt on findings if the study area population had changed substantially during that time frame; however, the population increased by less than 4% during this period. Another limitation is that this study focuses on a specific geographical region. Therefore, results cannot be extrapolated to other areas or locations. Moreover, sample size, and particularly the sample within the cluster (n=17), was also reduced to draw conclusions; therefore, some of our comments must be construed as merely preliminary (e.g., relationship between personality disorders and contagion). Furthermore, using data provided by the Institute of Legal Medicine of Malaga, we compared suicide rates among residents of the Antequera municipality with the suicide rate documented by the National Statistics Institute (INE in Spanish), because the suicide rate for Antequera inhabitants was not available in the INE. In any case, a recent study yet to be published describes the magnitude of differences in suicide rates documented by the Institute of Legal Medicine of Malaga and INE as being about 0.97 (±0.10).36 Although relevant, this difference does not affect this study's results. Finally, spatiotemporal cluster analyses fail to identify the mechanisms underlying suicide clusters. Field studies provide the best analysis for detecting underlying suicide cluster mechanisms.10

ConclusionsSpatiotemporal analyses are useful to identify specific suicide cluster cases and may help prevent some of them. At least in the Antequera community, Malaga, Spain, we recommend mental health public warnings to be issued during the first 2 weeks following a committed suicide (suicide index-case) and within a 2.5km radius of the affected area. Future studies will confirm these spatiotemporal limitations in other areas.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtecting people and animalsThe authors declare that this research does not include experiments on humans or animals.

Data privacyThe authors declare that they have followed workplace protocols on publishing patient data and that all patients included in the study have received enough information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained informed consent from those patients and/or subjects mentioned in this paper. For correspondence, the author is in possession of this document.

FundingThis study was funded by Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria Instituto de Salud Carlos III [Fund for Health Research of the Carlos III Health Institute] (PI061339), la Consejería de Salud de Andalucía [Andalusia Health Agency] (143/05; PI-0154/2007), and la Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia y Empresa [Innovation, Science and Development Agency]. Regional Government of Andalusia (CTS-546 PAIDI; PI10-CTS-05704). Dr. Blasco-Fontecilla acknowledges the funding aid from the Spanish Ministry of Health (Rio Hortega CM08/00170), the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation, and the Conchita Rabago Foundation for his post-doctorate stay in the Regional University Hospital of Montpellier, France. Dr. Yolanda de Diego-Otero is the recipient of a residency in the Nicolás Monarde (Program Servicio Andaluz de Salud, Consejería de Salud. Regional Government of Andalucía).

Contributions of authorsLucía Pérez-Costillas, Yolanda de Diego and Nicolas Benítez designed and developed this research.

Raquel Comino, José Miguel Antón, Valentín Ramos-Medina, Amalia López, Jose Luis Palomo, Lucía Madrigal, J. Alcalde and Emilio Perea-Milla collected data and contributed to the hypotheses and drafting the initial manuscript.

Hilario Blasco-Fontecilla, Victoria de León, Yolanda de Diego, Paula Artieda-Urrutia and Lucía Pérez-Costillas wrote most of the paper, except for the initial manuscript.

Victoria de León edited the paper's English version, and performed the critical analysis of the study.

Paula Artieda-Urrutia, Hilario Blasco-Fontecilla and Lucía Pérez-Costilla addressed and resolved the issues raised by both editors.

All authors approved the final version of this paper for publication.

Conflict of interestDr. Blasco-Fontecilla has received professional fees as a Speaker for Eli Lilly, Ab-biotics, and Shire. The other authors declare having no conflict of interest.

We thank Madeleine Gould, who provided us with some of her papers on suicide clusters and DWE Ramsden for reviewing the manuscript. We also thank Hugo Tobio-Suárez for improving the resolution of Fig. 1.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Costillas L, Blasco-Fontecilla H, Benítez N, Comino R, Antón JM, Ramos-Medina V, et al. Clusters de casos de suicidio espacio-temporal en la comunidad de Antequera (España). Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2015;8:26–34.