The disease COVID-19 produces serious complications that can lead to cardiorespiratory arrest. Quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can improve patient prognosis. The objective of this study is to evaluate the performance of the specialty of Anesthesiology in the management of CPR during the pandemic.

MethodsA survey was carried out with Google Forms consisting of 19 questions. The access link to the questionnaire was sent by email by the Spanish Society of Anesthesia (SEDAR) to all its members.

Results225 responses were obtained. The regions with the highest participation were: Madrid, Catalonia, Valencia and Andalusia. 68.6%% of the participants work in public hospitals. 32% of the participants habitually work in intensive care units (ICU), however, 62.1% have attended critical COVID-19 in the ICU and 72.6% have anesthetized them in the operating room. 26,3% have attended some cardiac arrest, 16,8% of the participants admitted to lead the manoeuvres, 16,8% detailed that it had been another department, and 66,2% was part of the team, but did not lead the assistance. Most of the CPR was performed in supine, only 5% was done in prone position. 54.6% of participants had not taken any course of Advance Life Support (ALS) in the last 2 years. 97.7% of respondents think that Anesthesia should lead the in-hospital CPR.

ConclusionThe specialty of Anesthesiology has actively participated in the care of the critically ill patient and in the management of CPR during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, training and/or updating in ALS is required.

La COVID-19 produce graves complicaciones que pueden derivar en parada cardiorrespiratoria (PCR). Una resucitación cardiopulmonar (RCP) de calidad puede mejorar el pronóstico de los pacientes. El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar el desempeño de la especialidad de Anestesiología en el manejo de la RCP durante la pandemia en España.

MétodosSe realizó una encuesta con Google Forms que constaba de 19 preguntas. El link de acceso al cuestionario fue enviado vía email por la Sociedad Española de Anestesiología y Reanimación (SEDAR) a todos sus miembros.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron 225 respuestas. Las provincias con mayor participación fueron: Madrid, Cataluña, Valencia y Andalucía. El 68,6%% de los participantes trabajan en la sanidad pública. Un 32% de los participantes se dedican habitualmente a los cuidados intensivos, sin embargo, el 62,1% ha atendido a enfermos COVID-19 en cuidados críticos y un 72,6% los ha anestesiado en quirófano. El 26,3% ha atendido alguna PCR, el 16,8% lideró las maniobras, el 16,8% no participó, y el 66,2% formó parte del equipo, pero no lideró la asistencia. La mayoría de las RCP se realizaron en supino, sólo el 5% fue ejecutada en prono. El 54,6% de los participantes no habían realizado ningún curso de Soporte Vital Avanzado (SVA) en los últimos dos años. El 97,7% de los participantes opinan que anestesia debe liderar la RCP intrahospitalaria.

ConclusiónLa especialidad de Anestesiología ha participado activamente en la atención del paciente crítico y en manejo de la RCP durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Sin embargo, resulta necesaria la formación y/o actualización en SVA.

In-hospital cardiac arrest (CA) is considered a life-threatening emergency, and evidence has shown a direct relationship between medical response and CA-related mortality. Each year, around 22 in-hospital cardiac arrests occur in Spain1. This is why it is vitally important to update the cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) algorithm and periodically refresh the staff’s CPR knowledge and skills. Hospitals are mandated to provide effective care to victims of cardiac arrest and, therefore, must ensure that their staff receive regular, up-to-date training that enables each worker to maintain a level of competence in accordance with their professional responsibility2. This training should be complemented with frequent short sessions to refresh the knowledge and skills learned. The current law on occupational health and safety calls for safe work environments in which workers are familiar with CPR3–5.

On 31 December 2019, the authorities of the People's Republic of China reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) an outbreak of several cases of pneumonia of unknown origin in Wuhan, a city located in the Chinese province of Hubei. In early January 2020, Chinese researchers sequenced the first genome of a new coronavirus isolated from a man working in the Wuhan seafood market. Using that first genome, scientists were able to track the SARS-CoV-2 virus as it spread around the world. On Wednesday, 11March 2020, the Director General of the WHO, Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus, declared the infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) a pandemic.

The first case was “diagnosed” in Spain on 31 January 2020 - a German patient admitted to hospital in La Gomera (Canary Islands) with a positive test result. The first “certified” death due to COVID-19 (acronym for coronavirus disease 2019, the infectious disease caused by SARS-CoV-2) in Spain occurred on 13 February - a 69-year-old male patient admitted to the Arnau de Vilanova Hospital (Valencia). However, the cause of his death was not known until March 3. COVID-19, therefore, was supposedly an unknown disease until December 2019.

COVID-19 is caused by one of the 7 coronaviruses known to infect humans, such as SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome). The RNA of SARS-CoV-2 contains more 30,000 nucleotides. Its receptor binding domain has a high affinity interaction with angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors on the surface of host cells. RNA from the virus enters cells of the upper and lower respiratory tract, and is translated into viral proteins. Other ports of entry are under investigation. The cell dies, releasing millions of new viruses that infect other cells and other individuals. The route of transmission between humans is believed to be similar to that described in other coronaviruses, namely, exposure to secretions from infected individuals, mainly by direct contact with respiratory droplets on the hand or on fomites contaminated with these secretions, followed by contact with the mucosa of the mouth, nose or eyes. Transmission by aerosolization in closed spaces or in droplets smaller than 5 μm could also be a secondary source of exposure. Like other members of the coronavirus family, this virus causes various clinical manifestations encompassed under the term COVID-19. They range from completely asymptomatic cases to respiratory symptoms ranging from the common cold to severe pneumonia with respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock and multi-organ failure. Most cases begin with mild symptoms, although up to 15% of those infected developed a severe form of the disease that requires hospital admission and support with oxygen therapy; 3%–5% of patient are admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICU)5–9.

In the current pandemic, action protocols have been changing in parallel with epidemiological developments and the emergence of new scientific knowledge. This prompted the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) to determine and review the state of the knowledge on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care, and to seek consensus on treatment recommendations. The results of the consensus were published by the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) at the end of April, and focus on the recommendation that CPR manoeuvres should never compromise the safety of health care workers10.

Knowing that one of the cornerstones of ongoing improvement is comparing results and organization systems, the CPR Working Group of the Spanish Society of Anaesthesiology, Resuscitation and Pain Therapy (SEDAR) conducted a short nationwide survey to evaluate the role of anaesthesiologist in the management of hospital cardiorespiratory arrest, particularly in the context of the current pandemic.

Material and methodWe drew up an online, 19-item questionnaire using the Google Forms app. The survey targeted anaesthesiologists working in Spain, and collected demographic data and their involvement in CA during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To achieve sufficient validity, all the researchers reviewed the questionnaire and added corrections and suggestions. SEDAR sent the link to the questionnaire to all its members in May 2020. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and by default authorised the inclusion of the information in the study. We hoped to obtain a large enough number of responses to obtain a true picture of the situation in Spanish, and for this reason the questionnaire was also uploaded to various social networks.

Statistical analysis was performed on Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 21 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA)

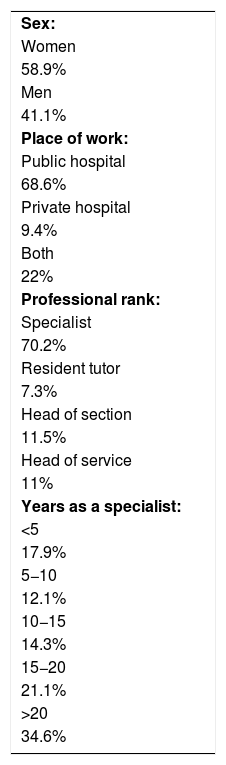

ResultsA total of 225 responses received and included in the study, representing 6.6% of SEDAR members. The communities with the highest number of respondents were Madrid (22.2%), Catalonia (18.2%), Valencia (13.8%) and Andalusia (10.2%). Other respondent demographics are shown in Table 1. Most (72.6%) respondents treated coronavirus-infected patients in the operating room; 62% of the total reported having treated critically ill COVID-19 patients during the pandemic; however, only 32% of participants were usually involved in intensive care.

Respondent demographics.

| Sex: |

| Women |

| 58.9% |

| Men |

| 41.1% |

| Place of work: |

| Public hospital |

| 68.6% |

| Private hospital |

| 9.4% |

| Both |

| 22% |

| Professional rank: |

| Specialist |

| 70.2% |

| Resident tutor |

| 7.3% |

| Head of section |

| 11.5% |

| Head of service |

| 11% |

| Years as a specialist: |

| <5 |

| 17.9% |

| 5−10 |

| 12.1% |

| 10−15 |

| 14.3% |

| 15−20 |

| 21.1% |

| >20 |

| 34.6% |

Some (26.3%) of the anaesthesiologists had performed CPR. Regarding the position in which CPR was performed, 84.6% answered that it was performed with the patient supine, 10.3% reported that the patient was in the prone position but was changed to the supine position to perform the resuscitation manoeuvres, and 5.1% of CPRs were carried out with the patient prone. In addition, 54.4% of respondents reported having evaluated patients in the peri-arrest period.

Leadership in CPRNearly all (97.7%) of respondents believed that anaesthesiologists should play a crucial role in in-hospital CPR: 45.3% believed that anaesthesiologists should be responsible for all in-hospital CPRs, while 52.4% believed that they should only be in charge of CPR in the surgical block and in postoperative critical care.

On the question of leadership in CPR, 16.8% of respondents answered that they led the cardiopulmonary resuscitation manoeuvres, 66.22% answered that although they had not led the CPR manoeuvres, they formed part of a team that was headed by a fellow anaesthesiologist, and the remaining 16.8% stated that another specialist was in charge of CPR; 85.3% of anaesthesiologists answered that they felt comfortable in the leadership role. The main reasons given for not feeling comfortable with this role were lack of training and practice in CPR, pressure, and stress.

Changes in the advanced life support algorithmHalf (55.5%) of the respondents confirmed that their CPR protocol had been modified due to the pandemic. Almost half (47.7%) based the changes on SEDAR recommendations, 28.8% based them on guidelines from their own hospital, 5.6% based them on the guidelines of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC), and the remaining 18% based them on other recommendations, particularly those published by the ERC.

CPR trainingOver half of the participants (54.9%) admitted not having taken a CPR training course in the last two years; however, 43.2% intend to do so. Of the respondents who had taken a course, 11.8% took a SEDAR course, 10.9% took a SEMICYUC course, and the remaining 22.7% took courses organised by other providers, particularly the Catalan Resuscitation Council (CCR).

DiscussionCOVID-19 causes several complications, the most serious of which are related to a sustained inflammatory response, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), cardiovascular involvement, and secondary infections11. The primary potential causes of SARS-CoV-2-related CA include hypoxia secondary to ARDS and cardiovascular problems. The cardiac complications found in patients with COVID-19 include: myocarditis, myocardial injury, ischaemic heart disease, arrhythmia, thromboembolic events, and cardiogenic shock11–14.

Only a few studies have reported the percentage of patients requiring CPR during the pandemic. Shao et al.15 studied data from 136 resuscitated patients, representing 17.8% of all hospitalized cases. Although we have no data on the percentage of patients requiring CPR in different Spanish hospitals, our study has shown that a significant number of respondents witnessed CPR at some time. Considering that the vast majority of anaesthesiologists have at some time treated patients with SARS-CoV-2 in the operating room or in critical care units, and that CRP is a frequent event in critically ill patients with COVID-19, we believe it is imperative that anaesthesiologists receive the training required to evaluate highly unstable, peri-arrest patients and perform high-quality CPR manoeuvres.

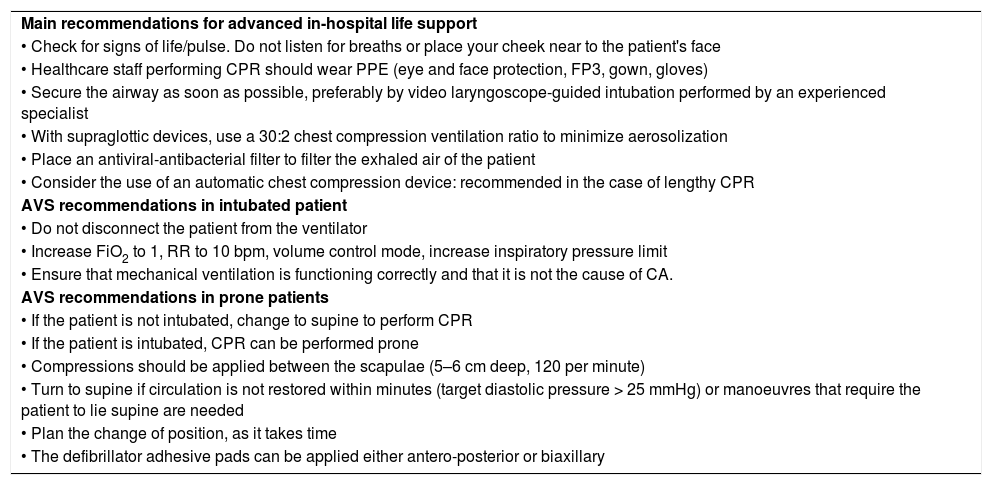

The pandemic has made it necessary to change CPR recommendations. As our survey shows, more than half of all respondents answered that the algorithms for advanced life support (ALS) have been modified in their workplace. The most important recommendations for AVS made by the ERC are listed in Table 210. Performing CPR while wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) can be more tiring than usual, so it appears to be necessary to change the person providing compressions every minute instead of every 2 min. It is also interesting to note that PPE must be loose fitting, so as not to restrict manoeuvres15. Prone CPR was first described by McNeil in 198916. Following this, several studies have concluded that the mean arterial pressure achieved during CPR in the prone position is adequate or even higher than that achieved with the patient in the supine position17,18. Due to the high incidence of COVID-19 patients ventilated in the prone position, it would appear reasonable to start CPR manoeuvres in this position, following the recommendations of various clinical guidelines (Table 2).

ERC recommendations.

| Main recommendations for advanced in-hospital life support |

| • Check for signs of life/pulse. Do not listen for breaths or place your cheek near to the patient's face |

| • Healthcare staff performing CPR should wear PPE (eye and face protection, FP3, gown, gloves) |

| • Secure the airway as soon as possible, preferably by video laryngoscope-guided intubation performed by an experienced specialist |

| • With supraglottic devices, use a 30:2 chest compression ventilation ratio to minimize aerosolization |

| • Place an antiviral-antibacterial filter to filter the exhaled air of the patient |

| • Consider the use of an automatic chest compression device: recommended in the case of lengthy CPR |

| AVS recommendations in intubated patient |

| • Do not disconnect the patient from the ventilator |

| • Increase FiO2 to 1, RR to 10 bpm, volume control mode, increase inspiratory pressure limit |

| • Ensure that mechanical ventilation is functioning correctly and that it is not the cause of CA. |

| AVS recommendations in prone patients |

| • If the patient is not intubated, change to supine to perform CPR |

| • If the patient is intubated, CPR can be performed prone |

| • Compressions should be applied between the scapulae (5–6 cm deep, 120 per minute) |

| • Turn to supine if circulation is not restored within minutes (target diastolic pressure > 25 mmHg) or manoeuvres that require the patient to lie supine are needed |

| • Plan the change of position, as it takes time |

| • The defibrillator adhesive pads can be applied either antero-posterior or biaxillary |

bpm: breaths per minute; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; RR: respiratory rate.

The most common cause of CA in COVID-19 patients is hypoxaemia, although there are also contributing factors, including sepsis, pulmonary thromboembolism, dehydration or hypotension. In these cases, the initial rhythm of CRP is usually non-shockable: asystole or pulseless electrical activity (PEA). CA due to cardiac causes, including myocardial ischemia, myocarditis, and ventricular arrhythmias secondary to drugs, is less common. These usually involve shockable rhythms: ventricular fibrillation (VF) and pulseless ventricular tachycardia (PVT), and have a better post-arrest prognosis15,19. It is important to bear in mind that many of the drugs used to treat COVID-19 can potentially cause adverse cardiac effects. In particular, remdesivir, lopinavir/ritonavir, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, interferon, methylprednisolone and tocilizumab can all cause arrhythmias, some of which, particularly in the case of azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine, and lopinavir/ritonavir, are due to QT prolongation, causing torsade de pointes12. In the aforementioned case series in Wuhan, 87.5% of CRPs were secondary to hypoxia, 7.3% were attributed to cardiac abnormalities, and the remaining 5.2% were attributed to other factors. The initial rhythm was asystole in 89.7% of patients, PEA in 4.4%, and shockable rhythm in 5.9%15.

Interestingly, our survey showed than 54.6% of respondents had not taken an ALS course in the preceding 2 years, although 43.2% intend to do so. This underscores the need for CPR education and training among anaesthesiologists.

The main limitation of this study has been the low participation rate. This could be due to, among other things, exhaustion on the part of anaesthesiologists after the pandemic, and the high number of questionnaires they receive on various subjects.

In conclusion, anaesthesiologists have been in the front line of care for critically ill patients due to COVID-19. In-hospital CA is common in these patients, so anaesthesiologists must be adequately trained to provide high-quality CPR that can improve the patient’s prognosis and give anaesthesiologists the confidence many feel they need to lead a CPR team.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Aliaño Piña M, Ruiz Villén C, Galán Serrano J, Monedero Rodríguez P. Resucitación cardiopulmonar durante la pandemia por COVID-19 en España. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2021;68:437–442.