Sjögren’s syndrome is an entity of rheumatic origin, with complex autoimmune characteristics, in which the salivary and lacrimal glands are mainly compromised. It has two forms of presentation, one primary and the other secondary, and in both forms there is evidence of exocrine glands involvement. The clinical spectrum of Sjögren’s syndrome is very heterogeneous and is classified into glandular and extra-glandular manifestations, but not mutually exclusive. It is recommended that all patients with parotid inflammation, purpura, hypergammaglobulinaemia, anti-SSa, and anti-SSb should be seen to have a greater risk of presenting with a severe systemic presentation, and it is recommended to carry out a more strict medical control. Population studies that have attempted to describe the incidence and prevalence of Sjögren’s syndrome in various countries throughout the world are to some extent discordant between one registry and another. Although Sjögren’s syndrome is more common in women, ocular involvement predominates in men, and it can occur in all ages, mainly between the third and fifth decades of life. In children it is rare. It is also considered as a common connective tissue disease, where the data on the global incidence rate and prevalence are underestimated.

El síndrome de Sjögren es una entidad de origen reumático, con características autoinmunes complejas, en la que se ven comprometidas principalmente las glándulas salivales y las lagrimales. Tiene dos formas de presentación, una primaria y otra secundaria, y en ambas se observa una afección de las glándulas exocrinas. El espectro clínico del síndrome de Sjögren es muy heterogéneo y se clasifica en manifestaciones glandulares y extraglandulares, no excluyentes entre sí. Se recomienda que se haga un control médico más estricto a todo paciente que curse con una inflamación parotídea, púrpura, hipergammaglobulinemia y anticuerpos anti SSa, anti SSb, puesto que presenta mayor riesgo de cursar con una presentación sistémica grave. Los estudios poblacionales que han intentado describir la incidencia y la prevalencia del síndrome de Sjögren en diferentes países, son hasta cierto punto discordantes entre un registro y otro. El síndrome de Sjögren es más frecuente en mujeres, pero en hombres predomina más la afectación ocular; puede presentarse en todas las edades, principalmente entre la tercera y la quinta década de la vida; en niños es raro. Se considera además como una conectivopatía frecuente, en la cual los datos de la tasa de incidencia global y de prevalencia se encuentran subestimados.

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a complex autoimmune rheumatic disease that mainly affects the salivary and lacrimal glands.1–5 The patients usually have ocular and oral dryness and glandular inflammation, which are evidenced by biopsy.6,7 Moreover, cutaneous, nasal and vaginal dryness is often observed.8,9 The classical triad of the disease that the vast majority of patients with SS exhibit is constituted by musculoskeletal pain, fatigue and dryness.10 Up to 30–50% of patients with SS may show systemic disease. In addition, there is an increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which occurs in a small percentage of patients.10

SS presents itself in a primary form, not associated with other diseases, and in a secondary form that complicates other rheumatic conditions.11–13 The most common diseases associated with secondary SS are rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.11

From the pathophysiological point of view, the main mechanism described is the intense lymphocytic infiltration of the exocrine glands, as well as the hyperactivity of B lymphocytes, which cause inflammation, damage to the glandular tissue and deterioration in its function.14,15

The global incidence of SS is estimated at approximately 7 per 100,000 person-years; however, the estimates of its incidence and prevalence vary widely depending on the specific classification criteria, the study design, and the population examined.16 According to the studies, the highest incidence rates were reported in Europe and Asia.17 In a study conducted in Colombia by Fernández-Ávila et al.,18 on the prevalence and demographic characteristics of SS, 58,680 cases of this disease were identified in the national territory, according to data obtained from the database of the Integrated Social Protection Information System. The researchers calculated a prevalence in people over 18 years of age of 0.12%, of whom 82% were women, with a female:male ratio of 4.6:1. The departments with the highest number of cases were Bogotá D.C. (24,885), Antioquia (9,040) and Valle del Cauca (5,277); however, the departments with the highest prevalence were Caldas (0.42%), Bogotá D.C. (0.32%) and Antioquia (0.14%). Although the SS can occur at any age, most patients are between the third and fifth decades of life, with a higher prevalence between 65 and 69 years of age.18

As in many chronic medical conditions, depression and anxiety can accompany SS, affecting the quality of life of the patients.19,20 This was demonstrated by means of the score in the Illness Intrusiveness Scale, implemented by Devin, in which the negative impact on the quality of life of the patients with SS is comparable to that of those with multiple sclerosis or renal replacement therapy.21 Therefore, it is important to establish an accurate diagnosis of SS through an exhaustive evaluation to expedite the referral to a specialist in a timely manner.22

The objective of this paper is to make a detailed description of the epidemiology and systemic clinical manifestations associated with SS, through a systematic review of the scientific literature, of a qualitative nature, presenting the evidence in a descriptive manner and without statistical analysis.

MethodologyInformation search strategyThe literature for this systematic review was identified through the approach to the following problem questions: What is the epidemiology of SS? What are the main clinical manifestations associated with SS syndrome?

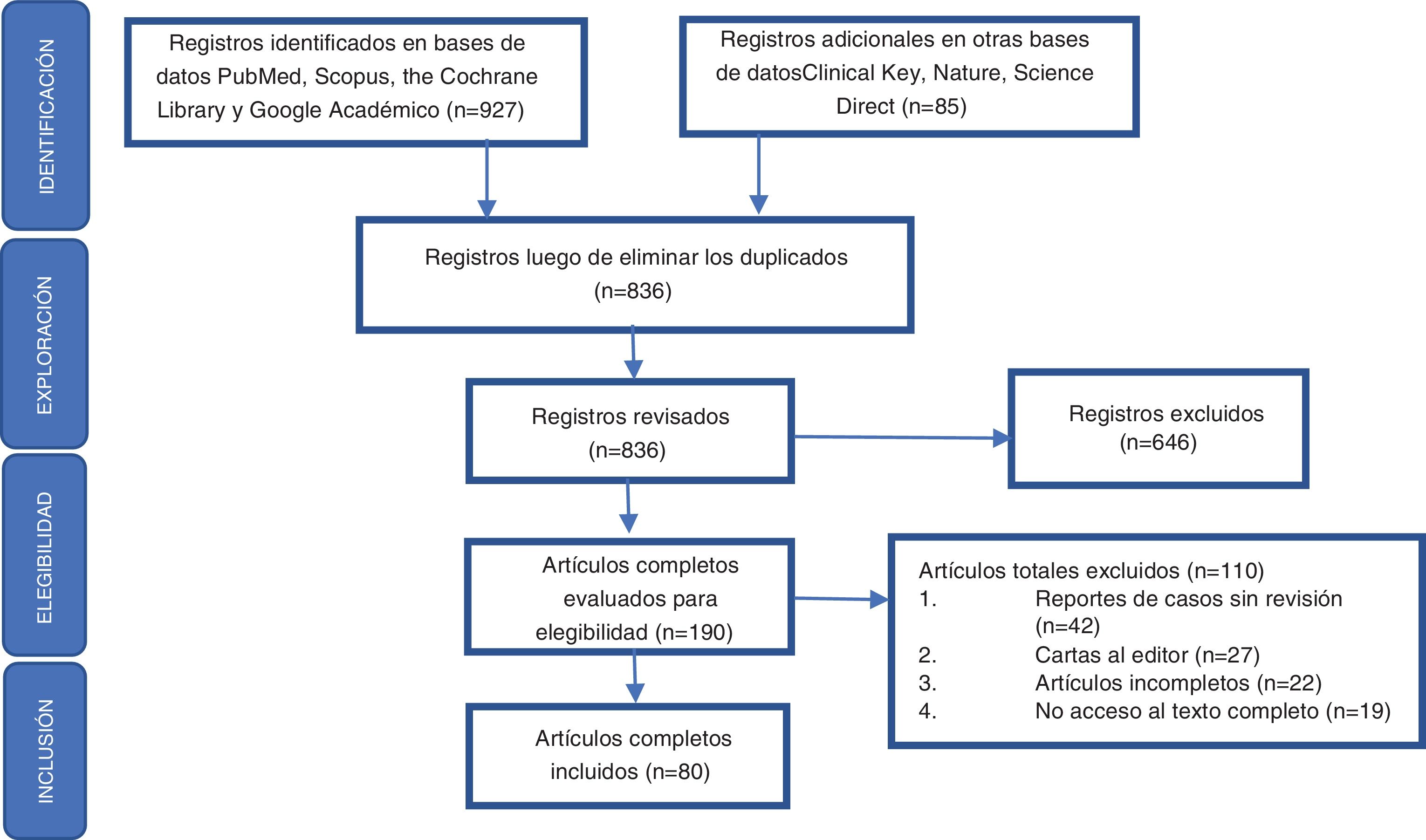

A systematic review was carried out, based on queries in the PubMed, Clinical Key, Scopus, the Cochrane Library, Nature, Science Direct and Scholar Google databases, searching for articles published until July 31, 2020. The following search criteria were used, designed from terms included in the DeC thesaurus (http://www.decs.bvs.br), or from their English equivalents included in the thesaurus MeSH (http://www.meshb.nlm.nih.gov): [Sjögren AND Manifestaciones clínicas] OR, [Sjögren AND Epidemiologia] OR, [Xerostomia AND Manifestaciones clínicas] OR, [Xerostomia AND Epidemiologia] OR, [Síndrome Seco AND Manifestaciones clínicas] OR, [Síndrome Seco AND Epidemiologia] OR, [Sequedad ocular AND Manifestaciones clínicas] OR, [Sequedad ocular AND Epidemiologia]. Additional information searches were performed in the lists of bibliographic references of the articles included in the study, in order to avoid the loss of relevant information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaAll articles found corresponding to systematic reviews, narrative reviews, or case reports, that included literature reviews, meta-analysis, and randomized controlled trials, were included. Articles that duplicated information contained in larger studies, letters to the editor, and articles that contained incomplete information or those for which access to the full text was not possible were excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment of the articles identifiedAccording to the problem questions posed, the authors were divided into 2 groups to carry out the identification of the literature, as a result of which a total of 836 records were obtained in the preliminary search, to then proceed according to the elements defined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement to perform the exploration, eligibility and inclusion of the records obtained in the respective bibliographic search (Fig. 1). After critical reading, 80 articles were selected and those which were considered relevant by the authors were ordered by topic, since they included a detailed review of the epidemiology and the glandular and extraglandular clinical characteristics related to SS. Priority was given to those publications included in indexed journals with a high impact factor according to the Journal Citation Reports (JCR). Subsequently, we proceeded to the analysis and development of the review.

Results and discussionEpidemiologySS constitutes an entity of autoimmune etiology, of unknown cause until now; not only its marked impact on the quality of life of the patients who present it is well known, but also the burden of disease that it means for caregivers and health systems worldwide.23 Effective therapeutic options are scarce and with this, the increase of this burden is propitiated.24 There are various population studies that have attempted to describe the incidence and prevalence of SS in different countries; the data are to some extent discordant between one registry and another, and will often depend on the diagnostic criteria used to classify the patients.25

Comparatively, the incidence rates of the studies that used the European classification criteria of 1993 were much lower, compared to those of the studies carried out according to the criteria of the European/American consensus of 2002.17 The global incidence rates range between 3 and 11 cases per 100,000 patients, while the prevalence is around 0.01–0.72%.26,27 Most likely these figures are underestimated, since many asymptomatic patients will never be diagnosed.28 As for the affectation by sex, it is much more frequent in women, with a ratio close to 10:1 (woman:man), which was reported in a study that included more than 14,000 patients.29 However, there are other differences in its behavior with respect to sex: severe ocular involvement predominates in men, while the manifestations and systemic involvement are much greater in women.30,31

Although it can occur at any age, most patients are between the third and fifth decades of life. In children is much rarer, maintaining the predominance in women, although in a lower proportion, with an average age of onset of the disease between 9.4 and 10.7 years, being girls younger at the age of diagnosis. Unlike adults, there is a lower incidence of dryness symptoms, but a higher incidence of mumps, lymphadenopathy, and systemic symptoms.32,33 The possible intervention of race or ethnicity has also been evaluated. In a study conducted in Paris (France) it was documented that the incidence was 2 times higher in the population without European ancestry than in that with European ancestry.34 A higher prevalence was documented in Asian populations, compared to Caucasian subjects.26 Likewise, variations were found between the studies of one country and another: this is the case of a prevalence of 0.21% in Turkey, where the criteria of the European/American consensus were used; 0.77% in the Chinese population, using the Copenhagen criteria, while the lowest rates were reported in Japan, between 0.03 and 0.05%.35–38

In Colombia, Santos et al.39 carried out a study whose main objective was to describe the prevalence of rheumatic diseases and associated factors in the Colombian population over 18 years of age, for which they included data from 6 major cities and used the Copcord (Community Oriented Program for the Control of Rheumatic Diseases) questionnaire adapted for Colombia. After this first step, the positive cases were evaluated at home by a first-year rheumatology resident, in the second instance they were evaluated by a second-year rheumatology resident, and finally, with the results of images and serological tests, they were evaluated by a certified rheumatologist. The researchers concluded that the prevalence of SS was 0.08%.39 These data are comparable to those published by Fernández-Ávila et al.,18 who analyzed slightly more than 58,000 cases of SS, from the database of the official registry of the Colombian Ministry of Health, most of the patients coming from Bogotá, Antioquia and Valle del Cauca, and found a total prevalence of 0.12%, which varies widely according to the age group evaluated, being lower in those under 15 years of age and higher in the population between 65 and 69 years of age (0.5%). The female population predominated, with a ratio of 4.63:1 (woman:man), which resulted in a prevalence of 0.31% in women and 0.07% in men.18

Clinical manifestationsThe clinical spectrum of SS is very heterogeneous and is operatively classified into glandular and extraglandular manifestations, which are not mutually exclusive.

Exocrine glandular manifestationsThe involvement of the exocrine glands in patients with SS is manifested mainly by hyposecretion, mediated by glandular disorders involved in the pathophysiology of the disease. These symptoms are the most frequent and represent the key point to reach the diagnosis, although they are only referred to by patients at the time of inquiring about them.40

Ocular diseaseXerophthalmia or keratoconjunctivitis sicca, which is the most common ocular manifestation in SS,41 appears as dryness and decreased lacrimation, pruritus, foreign body sensation, conjunctival hyperemia and photophobia,42 which generates alterations in the tear composition and flow, early breakage of the tear layer and lesions in the ocular epithelium. Likewise, it increases the probability of corneal ulcers, uveitis and scleritis43; in moderate to severe cases, optic neuritis and filamentary keratitis may occur, being the latter an entity in which protein fibers and mucous material adhere to the corneal surface, aggravating the dry eye symptoms.44

The prevalence of xerophthalmia reaches 15% of the general population, although less than 30% of this percentage has SS, this last entity affects about 90% of the patients diagnosed with xerophthalmia.44

Oral diseaseAt the oral level, xerostomia is a manifestation prevalently described by patients with SS.45 Saliva is a complex secretion that comes from the major salivary glands (parotid, sublingual and submandibular) in 93% of its volume and the remaining 7% from the minor or secondary glands (labial, palatine, genial and lingual glands) that are distributed throughout the oral cavity.46 It is composed of complex molecules such as proteins, glycoproteins, lipids, electrolytes, buffers, hormones, secretory immunoglobulin A, among other substances that play an important role in the maintenance of oral health.41 Therefore, complications related to the deficit in salivary production such as caries, early dental loss and recurrent oral infections by Candida albicans are usually present in patients with SS. These conditions are 10 times more frequent than in the general population, and manifest themselves as erythematous mucosal lesions, tongue fissures, atrophy of filiform papillae and angular cheilitis.13,47,48

It has also been reported that in 30–50% of patients with SS there is hypertrophy or enlargement of the salivary glands, which can start episodically or become chronic. Special care and vigilance must be taken in this case until infections are ruled out, and more importantly, lymphoma is ruled out with imaging tests or pathology studies, since the risk of developing a non-Hodgkin lymphoma throughout the life of a patient with primary SS is calculated in 4–10%.45

Other clinical manifestations at the oral level reported by patients with xerostomia (oral sicca) include: halitosis, dysgeusia, difficulty in speaking, difficulties in adapting dental prostheses and secondary eating disorders.49

Other exocrine glandular affectionsWithin the clinical spectrum of primary SS, nasal dryness has also been described in 30% of the diagnosed patients,25 manifested by nasal crusts that cause recurrent epistaxis as well as changes in smell and respiratory mechanics, which increase xerostomia when breathing with the mouth open while sleeping.40

Xerosis or dry skin is another frequent condition, found in 66% of patients with SS. Although the symptoms of this entity are non-specific, they are associated with specific signs such as inelastic, rough and desquamative skin, associated with hyposecretion of the sweat glands.50

On the other hand, it is not unusual to find vaginal dryness in the female population with SS, which presents with dyspareunia and predisposition to vulvovaginal infections.51 Even though the foregoing are multifactorial situations, they must be taken into account for the follow-up of the disease in these patients.

Extraglandular manifestationsAny organ or system can be affected with variable intensity by the pathophysiological phenomena of SS52; the clinical implications of the extraglandular system and non-exocrine glands are described in this section. These manifestations can occur at various stages of the disease, thus affecting its prognosis and severity.53

Musculoskeletal systemThe most common extraglandular manifestation in patients with SS is arthralgia and usually a non-erosive polyarthritis that occurs in approximately 50% of cases, which can appear before the dry symptoms in 20%, simultaneously in 50% and after these in about 30% of the patients.41,54 An elevated rheumatoid factor is characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis and is present in about 75% of the cases; however, it is also positive in 60–70% of the patients with SS, and for this reason it is not useful for distinguishing one disease from the other.41,55 Other manifestations include morning stiffness, symptoms of fibromyalgia, without disregarding that 70% of patients present fatigue and muscular involvement mainly in the form of myalgia. However, clinical pictures of proximal muscle weakness with insidious onset or mild inflammatory myopathy (polymyositis or inclusion body myositis) have been described.56

Between 13 and 65% of the patients show Raynaud's phenomenon, which can precede the symptoms of dryness and therefore constitute the first sign of the presence of a primary SS, which has also been related to the presence of arthritis, vasculitis, pulmonary fibrosis, glomerulonephritis, myositis and peripheral neuropathy.40,57

Hematological systemAmong the hematological disorders in patients with SS, anemia is characteristic in up to 30–60% of cases.31,58 Usually, this anemia is secondary to chronic inflammatory disease, however, cases of hemolytic anemia, pernicious anemia, and aplastic anemia have also been documented.40,41,59 Other present alterations include the affectation of the white series, which is manifested by leukopenia, lymphopenia or eosinophilia.58 The presence of polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia and cryoglobulins in serum is also frequent, and in the case of essential mixed cryoglobulinemia, the presence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) must be ruled out.40,60,61

Respiratory systemThe respiratory compromise found in SS ranges from the involvement of the upper respiratory tract to the small airways. The role of saliva as a buffer against gastric reflux is important; its deficiency, found in patients with SS, can cause cough and hoarseness.62

There are publications on SS and development of interstitial lung disease, a condition that affects up to 25% of the patients.63 Asymptomatic in the majority of cases, it can also cause progressive dyspnea, dry cough, pleuritic pain, and even pulmonary hypertension.63,64 Interstitial lung disease in SS has several forms of presentation, including nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis, and cryptogenic pneumonia.65 In asymptomatic patients is recommended a semi-annual or annual follow-up, in which imaging and respiratory function tests are performed.66

Cutaneous involvementCutaneous compromise, which is observed in at least half of the patients diagnosed with SS, presents with vasculitic manifestations such as hypergammaglobulinemic purpura (15%), leukocytoclastic vasculitis (11%), urticarial vasculitis (21%), intraepidermal deposits of IgG (66%), annular erythema and cutaneous lymphoma of B cells, whose exact incidence has not yet been reported.50 The histology reveals leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the superficial dermis, in addition to occasionally observing a mononuclear cell infiltrate that surrounds the vascular wall.40 Among the non-vasculitic cutaneous manifestations of SS is xerosis, previously mentioned in this review, being the most frequent, as well as nodular amyloidosis, alopecia, anetoderma, vitiligus, Sweet’s syndrome and lichen planus.66–68

Gastrointestinal systemIt has been argued that various gastrointestinal symptoms are part of SS and it has been proposed that they may be the result of lymphocytic infiltration of the gastrointestinal mucosa, or of the exocrine glands, due to autonomic neuropathies or to the development of associated autoimmune diseases.41 Within this spectrum we can find dysphagia, nausea, dyspepsia, atrophic gastritis with mononuclear infiltrates of the lamina propria and CD4 positive T cells, and achlorhydria.69 In patients with SS it is mandatory to investigate the presence of Helicobacter pylori, since it has been associated with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.40,70

At the level of the liver, SS is related to hepatomegaly and elevation of the liver enzymes, a finding observed in 10–40% of the patients.71 In addition, the diagnosis of HCV infection should be excluded from the study of SS, since these patients generally manifest symptoms related to sicca syndrome, although they have a lower prevalence of anti-Ro/La antibodies and hypertrophy of the parotid gland and a higher prevalence of hypocomplementemia, cryoglobulinemia, and liver disease.40,72 Other intestinal conditions described involve diarrhea, celiac disease, and pancreatic dysfunction.41

Urinary systemTubulointerstitial nephritis and renal tubular acidosis have been described as the most frequent forms of renal disease in SS, however, in the majority of cases they start in a subtle manner or asymptomatically.73 It is also frequent to see cases of glomerulonephritis, therefore, in case of suspicion, the possibility of underlying SLE or cryoglobulinemia should be excluded.74 The symptoms at the level of the bladder can be manifested with dysuria, pollakiuria, nocturia and urgency; if there is no urinary tract infection, the symptoms may be secondary to interstitial cystitis; these symptoms are 20 times more frequent in patients with SS than in the general population.40,75

Central and peripheral nervous systemsThe prevalence of neurological involvement in SS is approximately 20%, involving the peripheral nervous system (PNS) more frequently than the central nervous system (CNS).41 Neurological symptoms include headache and cognitive and affective dysfunction, the latter being reported in up to 70% of cases.41,76 Neuropathy usually precedes the diagnosis of SS in up to 81% of the patients77 and may present clinically as sensory-motor axonal symmetric polyneuropathy. This, which is the most frequent affectation of the PNS, begins with a predominance of sensory symptoms or with pure sensory neuropathy or with a “glove and stocking” peripheral neuropathy in more than 10% of patients.40,54,78

Sensory-motor axonal symmetric polyneuropathy generates mild and painless paresthesias of the distal lower extremities and may also involve the upper extremities in approximately 20% of cases. In this condition, denervation is not documented in electrophysiological studies,79 with the exception of the cases of small-fiber painful neuropathy, in which the electromyography may show concomitant involvement of long fibers and decreased epidermal nerve fiber density, or abnormal morphology in skin biopsies.40,80 Appearance of acute sensory ataxic neuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, and multiple cranial neuropathy has also been found.76

In the case of the CNS, manifestations such as transient hemiparesis, optic neuritis, seizures, ataxia, parkinsonism, aseptic meningoencephalitis, various forms of acute and chronic myelopathy, vasculitis, lymphomas, affective disorders, and dementia have been reported.40,41

Involvement of the thyroid glandIn addition to the implications of the exocrine glands documented in SS, the clinical symptoms that it produces at the level of the endocrine function of the thyroid are also notable, being well documented the cases of autoimmune thyroiditis with antibodies against thyroglobulin, antiperoxidase and against the thyroid hormones, which occurs in 15% of the patients. Non-autoimmune hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism have also been described, as well as thyroid hyperplasia.44,45

Table 1 shows a summary of the studies conducted in humans related to the glandular and extraglandular clinical manifestations in SS.

Summary of the studies related to the glandular and extraglandular clinical manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome.

| Author and year | Sample | Method | Objective | Type of study | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alani et al.1 | Selected studies = 42 in totalSLE + SS = 13 studiesTotal sample = 8,166 patientsTotal of patients with SS = 1,247 (15.2%)RA + SS = 19 studiesTotal sample = 6,626 patientsTotal of patients with SS = 855 (12.9%)SSc + SS = 7 studiesTotal sample = 1,108 patientsTotal patients with SS = 167 (15%)Myositis + SS = 3 studiesSSc + SS = 7 studiesTotal sample = 285 patientsTotal of patients with SS = 25 (8.7%) | Systematic search in the PubMed and Embase databases until March, 2016, to identify all published data on prevalence rates, demographic profile, clinical manifestations, laboratory characteristics, and causes of death associated with SS.The prevalence rates of SS were summarized with 95% CI. | To evaluate the PR rates and the clinical and serological characteristics of SS | Systematic literature review and meta-analysis | The combined PR for SS + RA was 19.5% (95% CI: 11.2–27.8), the PR for SS + SLE was 13.96% (95% CI: 8.88–19.04). The woman/man ratio of SS in the population with RA was 14.7 (95% CI: 7.09–256) and in the population with LUES was 16.82 (95% CI: 1.22–32.4) | The prevalence rates of SS vary widely in different populations. Both meta-analyses conducted in populations with RA and SLE were characterized by a high degree of heterogeneity. The results of this meta-analysis highlight the need for population studies of better quality |

| Sacsaquispe et al.24 | Total sample = 367 biopsiesMean age = 53 years (range: 13–86 years), with a predominance of women (90.2%) | Retrospective study in which the anatomopathological examination request forms and the histopathology slides were evaluated. The recorded data included age, sex, clinical characteristics and degree of severity. | To determine the epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and degree of severity of SS in biopsies from an oral pathology laboratory. | Retrospective cohort study | After analyzing the cases, it was found that xerostomia was manifested in 94.67%, while xerophthalmia was present in 81.52% of the cases; the systemic involvement predominantly observed was rheumatoid arthritis (34.17%), in addition to systemic sclerosis and erythematous lupus. The most common degrees of severity were 2 (36.42%) and 3 (33.9%). Some lymphoid follicles were also found; it is possible to evaluate the progress of the disease and detect the lymphoma early. | The study shows that 43.98% of the cases were diagnosed later in the course of the disease in grades 3 and 4, which suggests diagnosis in advanced stages of the disease. |

| Virdee et al.32 | Male population with SS: 7 studies included. Total sample = 210 patientsPediatric populations with SS: 5 studies included. Total sample = 132 patients | Search for articles in PubMed using the MeSH terms: «Sjögren’ syndrome», «men», «child», «pediatrics»; the data concerning epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics found in the male and pediatric populations with primary SS were extracted, to analyze them with help tools and later to break them down in tables. | To analyze the epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of male and pediatric patients with primary SS. | Cross-sectional study | The range of age at the onset of the disease was 9.4–10.7 years for children and 39.4–56.9 years at diagnosis for male patients. A prevalence of extraglandular manifestations between 52.6 and 92.3% was identified in the male population and between 50,0 and 84,6% in children, while abnormal sialometry was only reported in the pediatric population, with a prevalence between 71.4 and 81.8%. Significant variation of positive serological markers, with anti-Ro antibodies reported between 15.7 and 75.0%, and between 36.4% and 84.6%, and anti-La antibodies between 5.6 and 51.7%, and between 27.3 and 65.4%, in the male and pediatric populations, respectively. The characteristics of pSS in the male and pediatric populations varied among the different studies. Compared with the available data from adult populations with pSS, less dryness and higher prevalence of mumps, lymphadenopathy, and systemic and male symptoms were reported in children diagnosed with pSS; the patients were younger at the time of diagnosis. | The review contributes to a better understanding of the epidemiology of pSS in rare populations.Large longitudinal cohort studies that compare male with female patients and adult with pediatric patients are needed. |

| Zaldívar Pupo et al.48 | 150 full-text, refereed articles, written in English and Spanish, mainly from 2011 to June 2017 | An exhaustive bibliographic review was conducted in the main Infomed databases (SciELO Regional, Clinical Key, PubMed) from January 12 to June 25, 2017.There were no restrictions on the types of articles reviewed, although the original articles and bibliographic reviews were prioritized. | To update the oral signs and symptoms, as well as the stomatological management, in patients with SS | Systematic literature review | The main oral symptoms of SS are: burning and pain of mucous origin, dysgeusia, difficulty in phonation, formation of the alimentary bolus, mastication and deglutition. Among the oral signs are: loss of shine, pallor and thinning of the mucosa, inflammation and oral candidiasis. The stomatological treatment is carried out in 3 phases: initial, palliative and preventive, restorative and rehabilitative, and maintenance. | It is important to recognize and diagnose the oral signs and symptoms of the patient with SS, since these require special stomatological management. |

| Yayla et al.52 | Total sample = 352 patients with pSS | Retrospective study of the data of the patients who were subdivided into 2 groups:age of onset 35 years or younger (early onset) and age of onset older than 35 yearsThe clinical, laboratory and serological characteristics of the 2 groups were compared, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant | To investigate the clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients with early-onset primary SS | Retrospective observational study | 40 patients of the group with an age of onset of 35 years or less (11.4%) and 312 patients with an age of onset or more than 35 years (88.6%) were analyzed. The frequency of cutaneous (22.5% vs. 1.9%, p < 0.001) and renal (10% vs. 2.2%, p = 0.026) involvement was significantly higher in the early-onset group than in the late-onset group. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of xerostomia, eye dryness, arthritis and other systemic affections. Anti-Ro52 positivity (p = 0.04), increased serum levels of IgG (p = 0.004) and the low presence of C4 (p = 0.002) were more frequent in the early-onset group. | It was observed that the clinical phenotype of the patients with early-onset pSS may be different from that of those with late-onset. The more frequent observation of factors for poor prognosis at early onset ages, especially, shows the need to monitor these patients more regularly. |

| Payet et al.55 | Total sample = 294 patients16 ACPA-positive patients with pSS278 ACPA-negative patients | ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative patients with pSS were included in this study. For patients with positive ACPA, clinical and radiological reassessment was systematically performed after at least 5 years of follow-up. The diagnosis was reassessed at the end of the follow-up to identify the patients who developed RA according to the classification criteria of the American College of Rheumatology 1987. | To compare ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative patients with pSS and assess the risk of progression to RA | Cohort study | ACPA-positive patients had more frequently arthritis (43.7% vs. 12.2%; p = 0.003), but not arthralgia. They also had lung involvement more frequently (25% vs. 8.1%; p = 0.05). After a median follow-up of 8 (5–10) years, 7/16 (43.8%) patients developed RA, including 5 (31.25%) with erosions typical of RA. The elevation of acute phase reactants at inclusion was the only parameter associated with progression to erosive RA. | The middle term follow-up of the ACPA-positive patients with pSS showed that almost half of them developed RA, particularly in the presence of elevated acute phase reactants. These results support the usefulness of close radiological monitoring of these patients for the early detection of erosive changes and not delay the start of effective treatment. In fact, some of these patients with ACPA-positive pSS may have associated RA and SS. |

| Malladi et al.58 | Total sample = 1,927 participants registered in the SICCA registry | 886 participants who met the 2002 AECG criteria for pSS, 830 “intermediate” cases who had some objective findings of pSS but did not meet the AECG criteria, and 211 control individuals were selected. The prevalence of immunological and hematological laboratory abnormalities, and specific findings in the rheumatologic exam was studied; and the physician confirmed thyroid, liver and kidney disease, and lymphoma among the SICCA participants. | To study the prevalence of extraglandular manifestations in pSS among the participants enrolled in the SICCA | Cross-sectional study | Laboratory abnormalities, including the hematological, hypergammaglobulinemia, and hypocomplementemia, occurred frequently among the cases of pSS and were more frequent among the intermediate cases than among the control participants.Cutaneous vasculitis and lymphadenopathy were also more common among the cases of pSS. In contrast, the frequency of diagnoses of thyroid, hepatic and renal disease, and lymphoma confirmed by the physician was low, and only primary biliary cirrhosis was associated with the condition of the cases of pSS. Rheumatological and neurological symptoms were common among all the participants in SICCA, regardless the case status. | The data from the SICCA international registry support the systemic nature of pSS, which manifests mainly in terms of specific immunological and hematological abnormalities. The occurrence of other systemic disorders in this cohort is relatively uncommon. Previously reported associations may be more specific for selecting subgroups of patients, such as those referred for the evaluation of certain neurological, rheumatological, or systemic manifestations. |

| Abbara et al.64 | Total sample = 467 patients, of these, 21 with positive anti-RNP and 446 with negative anti-RNP | Patients who met the 2016 ACR/EULAR criteria for pSS and had anti-RNP antibodies, without other diagnosed connective tissue diseases and without anti-dsDNA antibodies, retrieved from the database of the French National Reference Center were selected and were compared with all other patients with pSS who were negative for anti-Sm, anti-RNP, and anti-dsDNA antibodies | To describe and compare the clinical and biological characteristics of subjects with pSS syndrome with and without anti-RNP antibodies. | Case-control studies | Anti-RNP positive patients had a lower median age at the onset of the symptoms of pSS (41.0 vs. 50.0 years, p = 0.01), a higher median EULAR SS disease activity index at the time of inclusion (8.0 vs. 3.0, p < 0.01), with a higher frequency of constitutional symptoms (14.3% vs. 0.01%, p < 0.01), myositis (19.0% vs. 2.3%, p < 0.01) and pulmonary involvement (19.0% vs. 5.7%, p = 0.04). In addition, anti-RNP positive patients had higher mean gamma globulin levels (22.5 vs.13 g/l, p < 0.01), more frequently anti-SSA antibodies (90.5% vs. 67.1%, p = 0.03), but less frequently lymphocytic sialadenitis with a focus score ≥ 1 (66.7% vs. 85.5%, p = 0.03). If the analysis is limited to anti-SSA positive patients, anti-RNP positivity is associated with the same clinicobiological characteristics, except for pulmonary involvement. | The patients with pSS and anti-RNP antibodies showed a more active systemic disease, with more frequent muscle and lung involvement, and increased gamma globulin levels, compared with anti-RNP negative patients. |

| Villon et al.68 | Total sample = 596 patients from 3 cohorts | Two French cohorts were used in which the prevalence of skin disorders was evaluated in 395 patients with pSS and diapSS. 91 consecutive patients with pSS were examined by a dermatologist and baseline data from the randomized TEARS trial. (110 patients with recent diagnosis or active pSS, treated with rituximab or placebo, and assessed for skin dryness using a visual analog scale of 100) | To determine the prevalence and importance of dermatological disorders in pSS | Cross-sectional study | The cutaneous manifestations included in the ESSDAI were rare in the ASSESS cohort (n = 16/395, 4.1%, mainly purpura; only 3 had high activity) but associated with activity in the other ESSDAI domains (peripheral nervous system (p < 0.001), muscular (p = 0.01), hematological (p = 0.017) and biological (p = 0.017)), history of arthritis (p = 0.008), splenomegaly (p = 0.024) and higher levels of gammaglobulins (p = 0.008). Compared with the patients with pSS who did not receive a dermatology consultation, the patients with pSS who had a dermatology consultation had significantly more dermatological involvement aside the ESSDAI score (42% [29/69] vs. 19.6% [11/56]; p = 0.008). The TEARS study showed a high prevalence of skin dryness (VAS > 50; 48.2%) and that these patients with dry skin had a higher VAS score (61.5 ± 28.2 vs. 46.8 ± 27.0; p = 0.003) and dryness (79.4 ± 15.2 vs. 62.5 ± 21.7; p < 0.0001). | The most common cutaneous disorder is dryness, which is associated with a higher level of pain and general subjective dryness. ESSDAI cutaneous activity is uncommon, associated with hypergammaglobulinemia and ESSDAI activity. The systematic dermatological exam is informative for non-specific lesions of pSS. |

| Guimarães et al.72 | The case of a 48-year-old female patient with chronic HCV infection and a diagnosis of discoid lupus with clinical characteristics of SS is described. | Description of the clinical case and review of the literature related to what is described | To illustrate how the presence of chronic HCV infection makes difficult the diagnosis of SS | Case report | The patient presented dry symptoms with hypocomplementemia and RF positivity, common characteristics in HCV + SS, while cryoglobulinemia was absent. However, she met the pSS classification criteria (positive anti-SSA antibody, ocular staining score higher than 5, and PCR negative for HCV-RNA). Even though the presence of arthritis and discoid lupus supports a primary rheumatic disease, normal inflammatory parameters, negative ANA, and salivary biopsy are less frequent in pSS. | In conclusion, the patients infected with HCV can present symptoms of dryness, and it can be difficult to differentiate the 2 entities, HCV + SS and pSS. A clinical scenery is described in which a patient infected with HCV with mixed characteristics between pSS and SS + HCV met the 2016 ACR-EULAR classification criteria for pSS and the RNA of the HCV is untraceable by the PCR technique. |

| Luo et al.73 | A cross-sectional study included 434 patients with pSS from the Department of Rheumatology of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University from 2013 to 2017 | Patients with renal involvement were compared with their age and sex matched controls (pSS without renal involvement). The demographic, clinical, histological, renal, and immunological characteristics of renal involvement in pSS were systematically analyzed. The possible factors related to renal involvement were identified by multivariate logistic regression analysis. | To investigate the different characteristics of renal involvement in patients with pSS and to identify potential factors associated with renal involvement | Cross-sectional study | 192 patients with pSS (88.48%) with renal involvement were women with a mean age of almost 58 years and a mean duration of disease longer than 4 years. The clinical, serological and immunological manifestations and the renal biopsy class of patients with pSS with renal involvement were presented. By multivariate analyses, the xerophthalmia, the histological positivity of the lower salivary glands biopsy (LSGB), the levels of complement 3 (C3) reduced anti‐SSA/Ro52, hypoalbuminemia and anemia maintained a significant association with renal involvement in pSS (all p < 0.05) | In addition to the LSGB pattern, the anti-SSA/Ro52 positivity, the reduced C3 levels, hypoalbuminemia and anemia also indicate a significant association with the renal involvement in pSS. Therefore, early surveillance is required for patients with these clinical manifestations. |

| Delalande et al.77 | Total sample = 82 patients (65 women and 17 men) with neurological manifestations associated with pSS | Eighty-two consecutive patients with pSS referred to the departments of Neurology or Internal Medicine of the University Hospital of Lille between January 1993 and December 2001 were retrospectively studied. All patients met the American-European criteria for SS and had neurological manifestations during the follow-up | To describe the diversity of neurological complications derived from SS | Retrospective observational study | The mean age of onset of neurological deterioration was 53 years. This neurological involvement often preceded the diagnosis of SS (81%); 56 patients had CNS disorders which were mostly focal or multifocal; 29 of the patients had spinal cord involvement (acute myelopathy [n = 12], chronic myelopathy [n = 16] or motor neuron disease [n = 1]); 30 patients had brain involvement and 13 patients had optic neuropathy. The disease mimicked multiple relapsing-remitting diseases, such as MS in 10 patients and primary progressive MS in 13 patients. Diffuse CNS symptoms were also registered: some of the patients had seizures (n = 7), cognitive dysfunction (n = 9) and encephalopathy (n = 2); 51 patient had involvement of the PNS Symmetrical axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy with predominance of sensory or pure symptoms, sensory neuropathy occurred most frequently (n = 28), followed by cranial nerve involvement affecting the trigeminal, facial, or cochlear nerves (n = 16). Multiple mononeuropathy (n = 7), myositis (n = 2), and polyradiculoneuropathy was also observed (n = 1). | The study underscores the diversity of neurological involvement of SS. The frequency of neurological manifestations that reveal SS and the high level of negativity of the biological markers, especially in patients with CNS involvement, could explain the high number of misdiagnosed cases. |

ACPA: anticyclic citrullinated protein antibodies; ACR/EULAR: American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism; AECG: American-European Consensus Group; ANA: antinuclear antibodies; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; MS: multiple sclerosis; SSc: systemic sclerosis; ESSDAI: EULAR Sjögren's Syndrome Disease Activity Index; RF: rheumatoid factor; CI: confidence interval; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; PR: prevalence; SICCA: Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance Registry; CNS: central nervous system; PNS: peripheral nervous system; SS Sjögren’s syndrome; pSS: primary Sjögren's syndrome; HCV: hepatitis C virus; LSGB: lower salivary gland biopsy.

SS is considered a frequent connective tissue disease in which data on the global incidence and prevalence rates are underestimated, and it is clearly much more frequent in women. There is evidence of special involvement of the salivary and lacrimal glands, but as observed here, there are extraglandular involvements and their symptoms can range from mild to severe. In addition, it is considered a model of autoimmune disease, in which a high risk of lymphomas can be present. It has an early onset form of presentation before the age of 35. It is recommended that all patients presenting with parotid inflammation, hypergammaglobulinemic purpura and anti-SSa and anti-SSb antibodies, who have greater risk of presenting with a severe systemic presentation, undergo a stricter medical control. Therefore, the role of the clinician to exhaustively detect the symptoms, clinical findings and laboratory results is very important, thus avoiding countless complications in the patients.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestNone.