Henoch-Schönlein purpura in the adult is a diagnostic challenge. Its low incidence and its unspecific symptomatology in this age group, establish a clinical chart that can be ignored on several occasions. Henoch-Schönlein purpura is considered a group of diseases of heterogeneous manifestation with a common pathogenic axis: the finding of inflammation of the wall of the small calibre vessels, mediated by immune complexes. The case is presented of a 70-year-old patient with a difficult to treat Schoenlein-Henoch purpura, with constant relapses despite the use of the therapeutic guidelines established in the current guidelines. In this patient, a concomitant cytomegalovirus infection was documented that, after receiving treatment, allowed adequate control of symptoms. Additionally, this patient also had a lymphocytopenia that was secondary to cytomegalovirus.

La púrpura de Henoch-Schönlein (PHS) en el adulto es un reto diagnóstico. Su baja incidencia y su sintomatología poco específica configuran un cuadro clínico que puede pasar desapercibido en diversas ocasiones o solaparse bajo el peso de diferentes sospechas diagnósticas. La PHS no es un cuadro de espectro único. Se considera un grupo de enfermedades de manifestación heterogénea con un eje patogénico común dado por el hallazgo de inflamación de la pared en vasos de pequeño calibre mediada por complejos inmunes. Este es el caso de un paciente de 70 años quien cursa con un cuadro compatible con púrpura de Henoch-Schönlein de inicio tardío caracterizada por su difícil manejo y constantes recaídas a pesar del uso cuidadoso de las pautas terapéuticas establecidas por los concesos actuales. En este paciente se documentó, de forma concomitante, una infección por citomegalovirus que al recibir tratamiento permitió el control adecuado de síntomas. Adicionalmente, este paciente presentaba una linfocitopenia que parecía ser secundaria a la infección viral.

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP) is an immune-complex (IgA)-mediated systemic vasculitis affecting the small vessels of the skin, the glomeruli, and the digestive system.1 Most cases develop during childhood, with an approximate incidence of 3.26/100,000 inhabitants.1 The prognosis in this age group may be benign.2 In contrast, its presentation in the elderly is unusual, representing less than 10% of the cases.3 A number of case series seem to indicate that adults normally have a positive response to conventional therapy, but this treatment may be controversial due to the lack of clinical controlled trials with concrete supporting evidence.4 This is the case of a 70-year old male, diagnosed with HSP, with multiple relapses despite high-dose corticoid therapy, associated with cytostatic protocols. Additionally, the patient developed cytomegalovirus infection which seemed to contribute to the perpetuation of active immunity phenomena or to imitate symptoms associated with the refractory nature of the condition. There are 4 cases reported in the literature which have associated cytomegalovirus with HSP. These 4 cases report patients with new onset renal disorders and findings compatible with HSP. Once vasculitis treatment was introduced, the patients experienced intestinal bleeding episodes with histopathological exams compatible with cytomegalovirus infection. The fundamental difference with our case is the documented lymphocytopenia, potentially linked to the viral infection.

Clinical case70-year old male patient, salesman, with no remarkable medical history, who was referred from another institution after 15 days of presenting with generalized pruritic purpuric lesions, associated with renal dysfunction. The physical examination revealed confluent maculae and purpuric plaques in the lower extremities. High doses of steroid pulses were initiated, with a suspicious diagnosis of ANCA positive vasculitis. The patient presented with several outbreaks with the same characteristics over the past 8 years, which occurred episodically and with asymptomatic periods of time in between crisis, with an adequate initial response to steroids and a skin biopsy-based diagnosis of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Additionally, the patient had experienced intense abdominal pain of unclear etiology on several occasions. When completing the steroid therapy, the renal function recovered fully. A study was initiated requesting an immune profile and kidney biopsy which reported mesangial proliferation with IgA deposits. HSP of the elderly patient was diagnosed.

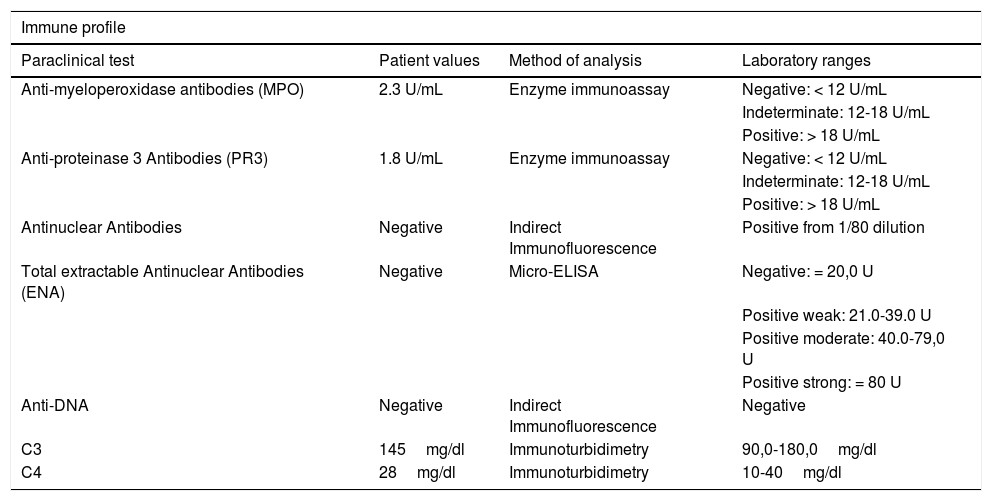

The patient was admitted a few months later, with a similar presentation as the above described (Fig. 1). Further tests were conducted to rule out neoplastic causes, including multiple myeloma with negative results, as was also the autoimmunity profile (Table 1).

Patient immune profile.

| Immune profile | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Paraclinical test | Patient values | Method of analysis | Laboratory ranges |

| Anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies (MPO) | 2.3 U/mL | Enzyme immunoassay | Negative: < 12 U/mL |

| Indeterminate: 12-18 U/mL | |||

| Positive: > 18 U/mL | |||

| Anti-proteinase 3 Antibodies (PR3) | 1.8 U/mL | Enzyme immunoassay | Negative: < 12 U/mL |

| Indeterminate: 12-18 U/mL | |||

| Positive: > 18 U/mL | |||

| Antinuclear Antibodies | Negative | Indirect Immunofluorescence | Positive from 1/80 dilution |

| Total extractable Antinuclear Antibodies (ENA) | Negative | Micro-ELISA | Negative: = 20,0 U |

| Positive weak: 21.0-39.0 U | |||

| Positive moderate: 40.0-79,0 U | |||

| Positive strong: = 80 U | |||

| Anti-DNA | Negative | Indirect Immunofluorescence | Negative |

| C3 | 145mg/dl | Immunoturbidimetry | 90,0-180,0mg/dl |

| C4 | 28mg/dl | Immunoturbidimetry | 10-40mg/dl |

There was evidence of extremely elevated PTH, so a gammagraphy was conducted which reported a parathyroid adenoma that was excised. Cyclophosphamide therapy was initiated at a 750mg dose (administered monthly for 6 months). Following the first dose of the cytostatic agent the patient’s symptoms resolved and was discharged to continue with ambulatory therapy.

Two months later the patient was re-admitted due to a new presentation of generalized palpable purpuric lesions associated with anasarca. High dose steroid pulses were initiated, which totally and rapidly resolved the condition. A few weeks later the patient was readmitted, with a cutaneous relapse involving GI bleeding secondary to gastritis, which was successfully controlled endoscopically. Once the GI bleeding was resolved, steroid pulses were administered. By then, the patient had received several cyclophosphamide courses and chronic steroid management with high doses of azathioprine was prescribed.

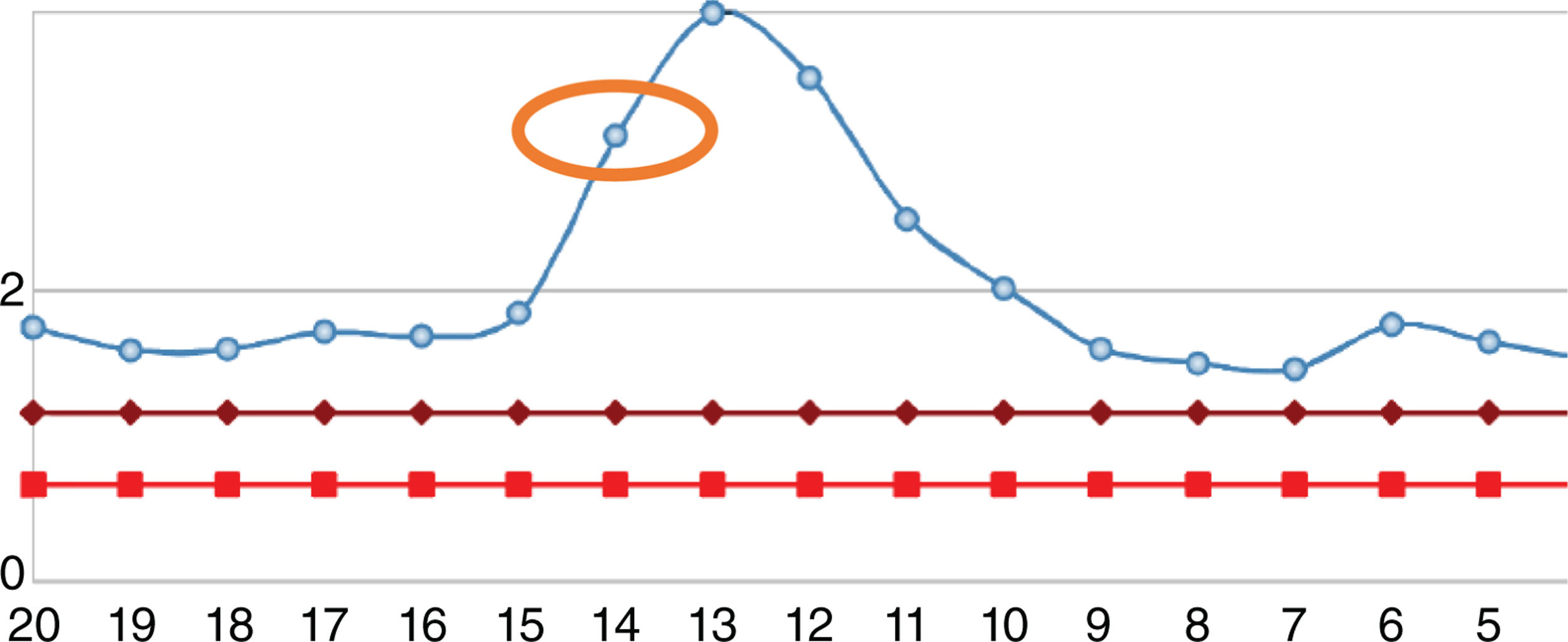

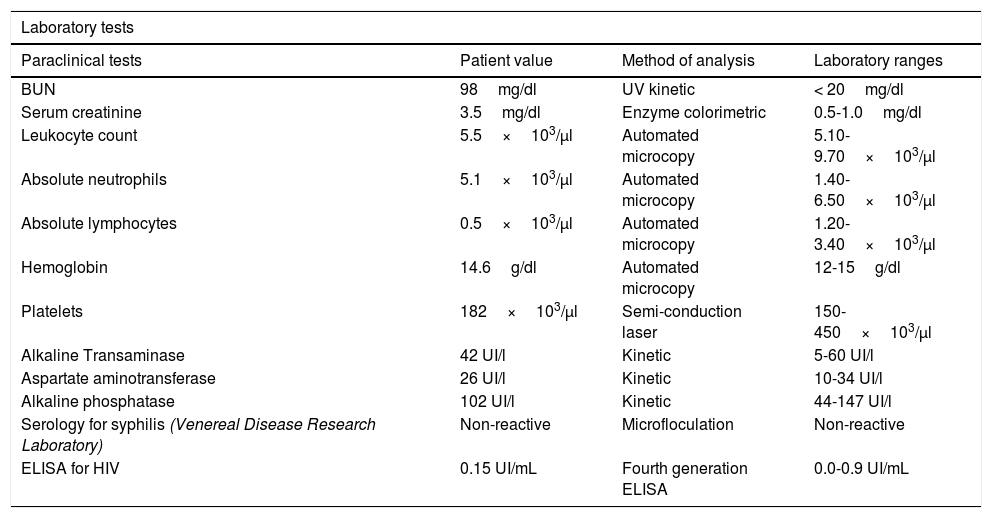

After one year, the patient was readmitted with new intermittent purpuric lesions with six months of evolution, associated with edema of the lower limbs and a decline in functional class. At admission, elevated nitrogen compounds were recorded and a blood test was performed. The only finding was lymphocytopenia – which initially was considered irrelevant – elevated acute phase reactants and chest x-ray with scarce bilateral pleural effusions (Table 2). IV steroid boluses were re-initiated at a dose of 1g of methylprednisolone per day, for 3 days. A complementary uranalysis showed active sediment with proteinuria and hematuria; the kidney ultrasound did not show any changes in chronic kidney disease and the 24h protein collection was within the chronic nephropathy range. Acute kidney injury was established due to a probable rapidly progressing glomerulonephritis. The opinion of the rheumatologists was that due to numerous relapses and the refractory autoimmune pathology, the patient could benefit from rituximab; tests for infectious diseases were initiated, including ELISA for HIV, hepatotropic virus profile, and tuberculin test which were all negative. During hospitalization, the patient developed rectal bleeding with secondary anemia, which led to hypovolemic shock. The abdomen CT evidenced megacolon. The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy and total colectomy for bleeding control. The progressive worsening of lymphocytopenia during the postoperative period was remarkable and hence a CD4 count was requested, in addition to polymerase chain reaction for cytomegalovirus and histological review of the colectomy specimen. The CD4 count reported total lymphocytes of 72. The polymerase chain reaction for cytomegalovirus was positive and the viral load was 1,143. Ganciclovir antiviral therapy was initiated. The biopsy reported edema of the colon wall, areas of bleeding and giant cells with intracellular inclusions. Cytomegalovirus eye involvement was ruled out. After completion of the antiviral treatment, the patient experienced a progressive increase in the lymphocyte count (Fig. 2), while the nitrogen compounds slowly began to drop (Fig. 3). One year after the last crisis, the patient has not had any more relapses and continues with low dose steroid therapy, with adequate control of the disease.

Paraclinical tests of patient at last hospital admission.

| Laboratory tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Paraclinical tests | Patient value | Method of analysis | Laboratory ranges |

| BUN | 98mg/dl | UV kinetic | < 20mg/dl |

| Serum creatinine | 3.5mg/dl | Enzyme colorimetric | 0.5-1.0mg/dl |

| Leukocyte count | 5.5×103/µl | Automated microcopy | 5.10-9.70×103/µl |

| Absolute neutrophils | 5.1×103/µl | Automated microcopy | 1.40-6.50×103/µl |

| Absolute lymphocytes | 0.5×103/µl | Automated microcopy | 1.20-3.40×103/µl |

| Hemoglobin | 14.6g/dl | Automated microcopy | 12-15g/dl |

| Platelets | 182×103/µl | Semi-conduction laser | 150-450×103/µl |

| Alkaline Transaminase | 42 UI/l | Kinetic | 5-60 UI/l |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 26 UI/l | Kinetic | 10-34 UI/l |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 102 UI/l | Kinetic | 44-147 UI/l |

| Serology for syphilis (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory) | Non-reactive | Microfloculation | Non-reactive |

| ELISA for HIV | 0.15 UI/mL | Fourth generation ELISA | 0.0-0.9 UI/mL |

Evolution of leukocyte count of the patient. The normal range is represented by the red line. The blue line represents the patient’s values. The orange circle represents the level on the date the patient underwent colectomy. The green circle is the number of lymphocytes at discharge.

There are no large consensus reports in the literature about HSP in elderly patients. Its low incidence is notorious and there is a significant underdiagnosis. Consequently, the approach and management of this condition are mostly based on expert consensus and international series, in addition to the clinician’s expertise. The etiology of HSP is unknown.5 Similarly to other autoimmune diseases, genetics and environmental factors apparently play a key role in the development of the disease.6 Several factors have been linked to the development of HSP, including infections (the prevalence of streptococcus as the most frequently associated microorganism is remarkable), drugs and some tumors.7

There is a wide range of pathological alterations that account for the heterogeneity of the clinical presentation, but the most common are: skin vasculitis lesions, abdominal pain and kidney disease.8 Skin findings are the most frequent manifestations and there is a difference between the macro and microscopic characteristics of the child and the elderly patient, with a prevalence of the hemorrhagic and necrotic forms of the disease among the elderly, usually presenting as symmetrical purpuric papules and plaques of varying sizes and distribution.9,10 Renal involvement seems to determine the prognosis of the disease.3 In children, glomerular disorders are rare, while in the elderly its prevalence ranges from 50 to 80% and represent an evolving and dynamic condition that may become significant.11 Approximately half of the patients develop GI involvement and usually the abdominal pain is the result of intestinal wall ischemia.12 According to the literature, the most frequent finding in the kidney biopsy is focal and segmented proliferative glomerulonephritis, sometimes associated with crescent formation.13,14

For several decades, another major difficulty of HSP in the elderly was the establishment of reliable diagnostic criteria that were not based on age as the primary factor. In the last few years, the European Society of Pediatric Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR/PReS) suggested new criteria, removing age as the major consideration, in order to enable the inclusion of any age groups in the diagnosis.12,15

There is a clear and frequent relationship between autoimmunity and neoplasms. The coexistence of HSP and malignant tumors – most frequently solid tumors such as lung, prostate, breast and stomach cancer – has been described.16 This association makes it mandatory to rule out the presence of a lesion conducive to paraneoplastic syndromes in elderly patients.17

The primary clinical control measure is aimed at the resolution of acute symptoms in the treatment of adult HSP.18 Kidney function is the basis to decide on changes in therapy. Unfortunately, treatment guidelines have not been specifically assessed in adults and most studies have been conducted in pediatric populations. As previously mentioned, there are no generally accepted treatment guidelines supported by meticulous studies.19 The case series reviewed for this report suggest the administration of high-dose oral steroids, with potentially significant benefits to control the skin and abdominal symptoms, and to reduce the risk of short-term kidney failure.14,20 Other immunosuppressors used in HSP with severe manifestations or refractory to steroids, do not have any strong evidence in adults, and most trials have been conducted in pediatric populations.19 Apparently there is some evidence indicating that although steroids are effective for symptom resolution, this therapy fails to reduce the relapse of nephritis in the long term.21,22 There is limited evidence to support an effective treatment to prevent renal complications and mitigate morbidity. A retrospective trial comparing the combined steroid-cyclophosphamide therapy versus steroid only, failed to show any benefit from this combined approach.23 The evidence of rituximab to control the disease is discussed in some case reports; the experience with biologics is poorly documented. Fenoglio et al.21 present a case series of 5 patients with poor steroid treatment response and other cytostatic agents that effectively respond to anti-CD20 therapy, with nephritis control and complete resolution of symptoms.

Second to retinitis, cytomegalovirus-associated colitis is the second most common entity in immunocompromised patients with disseminated cytomegalovirus infection.24 In immunocompromised patients, colitis seems to be secondary to the reactivation of the virus.24 The histopathological samples are characterized by basophilic intranuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions.25 One of the most severe complications of this condition is toxic megacolon, a condition with a significant morbidity and mortality, that requires emergency surgical management.25,26

The origin of the lymphocytopenia is difficult to establish in this particular patient. The drugs used to control his autoimmune disease may predispose to the depletion of CD4. However, there are apparently some cases of retroviral infections (different from human immunodeficiency virus) that may trigger lymphocytopenia, which recovers once the acute infection resolves, or following the introduction of antiviral therapy.27 Díaz et al.27 published 6 case reports of patients with severe CD4 deficiencies who developed cytomegalovirus infections and Epstein-Barr, and recovered their immune status after the administration of antiretroviral therapy with ganciclovir.

A multicenter trial conducted in Japan by Dr. Takizawa’s group28 apparently showed that in patients with autoimmune diseases, lymphocytopenia may be a high risk factor for cytomegalovirus infection. The lymphocyte count at the time of diagnosis was significantly associated with the presence of cytomegalovirus infection (p=0.009), irrespective of the antibody titers or the extent of the viral load.28 Another trial conducted at the Peking University People's Hospital, with 263 patients with autoimmune disease, found that 62 patients had cytomegalovirus infection, and the findings correlate the reduction of CD4 as a risk factor for the development of this clinical condition. This study seems to show the co-existence of lymphocytopenia and cytomegalovirus infection in rheumatological patients.29 There are some case reports of cytomegalovirus colitis with severe idiopathic lymphocytopenia in which the patient’s immune condition improved upon resolution of the viral infection; however, the authors fail to conclude any relationship between the antiretroviral therapy and immune recovery.21

There are reports that link the cytomegalovirus infection to complications in some conditions such as systemic lupus erythematous (SLE). Cytomegalovirus has been associated with mimicking diseases such as SLE.30 Cytomegalovirus infection may mimic lupus-like flares and some cases have been reported in which the GI and lung viral involvement is misinterpreted as organ-specific manifestations due to immune activity.31 Similarly, there are reports describing cases of patients that develop SLE following a cytomegalovirus infection.32–34 We found 4 case reports in the literature associating HSP with cytomegalovirus infection. D’Alessandro et al.35 described the case of a 3-year old girl, not immunocompromised, who developed a condition compatible with HSP. The anatomopathological study determined necrotizing vasculitis and cytomegalovirus-associated inclusion bodies.35 Nguyen et al.36 reported in 1997 a case of a patient with HSP and developed hematochezia. The anatomopathological examination in this patient showed intestinal alterations attributable to vasculitis and concomitant cytomegalovirus infection. This case shares several characteristics to the patient herein discussed: a patient presenting with kidney failure attributable to HSP, who developed low GI bleeding and with a histological specimen compatible with cytomegalovirus colitis and changes secondary to vasculitis, attributable to his autoimmune disease. The third case was reported in Japan and described a male, 55-year old patient admitted with arthralgia, melena and edema of the lower extremities. Hyperazotemia associated with hematuria and massive proteinuria was documented. The histological diagnosis was compatible with HSP, and steroid management was initiated. When the vasculitis began to resolve, the patient developed GI bleeding and died. The autopsy revealed ulcerative hemorrhagic lesions compatible with cytomegalovirus colitis.37 The last and most recent case was reported in Korea involving a patient with small cell lung cancer who developed HSP concomitant with cytomegalovirus duodenitis.38 These 4 cases differ from the case herein discussed because of the patients’ immune status. These patients had adequate CD4 counts leading to a debate about the use of antiretroviral therapy.38

An effective treatment for autoimmune diseases concomitant with cytomegalovirus infection should be aimed at halting the immune activity, achieving a negative viral load, and avoiding an antagonistic result. Being able to control the infection and modulating the vasculitis with the same therapeutic regimen would be ideal, and could facilitate the clinical approach by reducing the rate of adverse effects, drug interactions, and facilitating the administration of medicines. An interesting proposal is leflunomide. There are case reports of patients with cytomegalovirus infection resistant to conventional therapies, in whom the infection was controlled and the viral load became negative with the use of leflunomide.39 Similarly, a study conducted by Zhang et al. in 2014,40 showed that in patients with kidney disease secondary to HSP, presenting with proteinuria in a nephrotic range, the use of leflunomide in combination with steroids (versus steroids alone), significantly improved the GFR and reduced the urinary protein excretion. Notwithstanding the fact that this is a unique study in the world, with a small number of participants, it does provide for a new therapeutic approach for HSP.

ConclusionIn this case, the control of the autoimmune disease was only accomplished upon the administration of an effective therapy against the viral infection. The patient has not experienced any further relapses and the control of symptoms has been adequate after the use of the antiretroviral therapy. There was disease remission and the kidney function stabilized, with adequate response to the therapies usually used for HSP. This report seems to support the idea that there are situations of lymphocytopenia considered to be idiopathic, but may be secondary to viruses other than the human immunodeficiency virus. Furthermore, when comparing this particular case against the 4 reports of HSP associated with cytomegalovirus infection, it is possible to conclude that any manifestations secondary to cytomegalovirus may be a complication of the immunosuppressive therapies used in autoimmune diseases. Cytomegalovirus infection presents in clinical settings with an existing relevant predisposing factor. Opportunistic infections will further complicate the development of the disease and make its approach even more difficult. Nonetheless, failure to provide adequate immunosuppressive therapy in case of systemic vasculitis may result in poor outcomes and lead to increased morbidity. Hence, there is a need to suggest a therapy able to modulate the activity of systemic vasculitis and prevent potential mortality, and simultaneously control the opportunistic infection, or at least avoid making it worse. Occasionally, the infection may be a confounding factor and an obstacle to start early treatment to control the vasculitis activity. This results in delayed treatment and impacts the prognosis of the disease, in addition to increased morbidity or death. Consequently, developing a treatment able to simultaneously stop the progress of the autoimmune disease and treat the opportunistic infection, so that improvement in one does not worsen the other, may result in greater clinical efficacy and better outcomes.

A further conclusion was that any patient with vasculitis receiving immunosuppressive therapy who develops low GI bleeding, should be suspicious for cytomegalovirus colitis as a differential diagnosis. In case of HSP with GI bleeding, the most likely etiology is the disease activity itself, or adverse reactions to certain immunosuppressors; once the usual causes are ruled out, cytomegalovirus should be a primary diagnostic consideration.

FinancingNo funding sources were used in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe author has no conflict of interests to disclose.

Please cite this article as: Duarte EV. Infección por citomegalovirus en Púrpura de Henoch–Schönlein del anciano como complicación y factor perpetuador de la enfermedad. Reporte de caso. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2021;28:57–63.