This article explores the structure of the network of actors involved in the care of individuals with unhealthy alcohol use (UAU) at the primary care level in five primary care centers in Colombia between 2017 and 2018. We use the Actor-Network Theory Framework (ANT) which posits that health outcomes are a product of a multitude of relationships between different stakeholders. The article focuses on the network configuration that develops between the actors and its effects on the processes of identification, care, and follow-up of people with UAU. The data come from five care centers that participated in the pilot phase of an implementation research project that seeks to apply evidence-based interventions for the detection and treatment of depression and unhealthy alcohol use. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups (FG) were conducted with patients, health and administrative staff, and users from Alcoholics Anonymous. The interviews were transcribed and coded using N-Vivo. The analysis identified the ways in which actors are linked by the community to UAU. The results of this qualitative approach based on ANT present the actors identified in a non-linear network with different dimensions.

Este artículo explora la estructura de una red de actores involucrados en el cuidado de individuos con consumo no saludable de alcohol (CNA) en cinco centros de atención primaria en Colombia entre los años 2017 y 2018. Se utilizó el Actor-Network Theory Framework (ANT), marco teórico que propone que los resultados en salud son producto de una multitud de relaciones entre distintos actores. Este artículo se enfoca en la red de configuración desarrollada entre actores y sus efectos en el proceso de identificación, cuidado y seguimiento de personas con UNA. Los datos provienen de cinco centros de salud que participaron en la fase piloto de implementación de un proyecto de investigación que busca aplicar intervenciones basadas en la evidencia para la detección y tratamiento de la depresión y el uso riesgoso de alcohol. Se condujeron entrevistas semiestructuradas y grupos focales con pacientes y personal médico y administrativo. Las entrevistas fueron transcritas y codificadas utilizando N-Vivo. El análisis identifica las maneras en las que los actores se vinculan a la red. Los resultados de este acercamiento cualitativo basado en ANT presenta a los actores identificados en una red no linear con distintas dimensiones.

Risky alcohol consumption is a global and large-scale problem that strongly affects Latin-American countries. Indeed, as evidenced by the World Health Organization (WHO), “one in five drinkers (22%) in Latin America have episodes of excessive drinking, a percentage that exceeds the global average (16%)”.1 According to the Clinical Practice Guidelines for early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with unhealthy drinking and alcohol use problems, the consumption of alcohol in Colombia is both widely accepted and promoted.2 The Colombian 2015 National Mental Health Report3 showed that unhealthy drinking is the most prevalent disorder amongst all substance use disorders and estimated that one out of 15 Colombians is an unhealthy drinker, with a ratio of men to women of 5 to 1. Unhealthy drinking is also related to traffic accident deaths as well as to mental health disorders such as depression.

From the primary health care (PHC) perspective, it is expected that health teams address unhealthy drinking by defining preventative strategies that aim to reduce its burden on the population, as well as identifying and offering care of individuals with unhealthy drinking behaviors. However, in Colombia, primary care has not comprehensively assumed responsibility for detecting and providing treatment for unhealthy drinking, largely due to a lack of confidence in their capacity to provide effective interventions. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that primary care, with adequate training and support, can effectively address these problems.4,5

ContextThe General System of Social Security in Health (GSSSH) is a redistributive system organized and monitored in Colombia by the state, with both public and private entities acting as health service providers. Individuals are linked to the system through affiliation to a Health Insurance Agency (HIA) that guarantees access to health services offered by Health Care Providers (HCP), which are either private or State-Owned Institutions (SOI). The HIA’s are responsible for administrating resources, organizing and providing services to ensure effective access to health care under a comprehensive health care model including promotion, prevention, treatment as well as subsequent rehabilitation. The HCP is responsible for providing direct health care to the population, and is composed of hospitals, health centers, and health professionals that develop and provide these services.

With the formulation of the 1438 Law6 in 2011, the health system in Colombia was reoriented in order to focus on prevention and PHC. This law sought to shift health provision towards a comprehensive and integrated primary care system in which the health team is responsible for the identification of patients with problematic alcohol consumption, the provision of appropriate interventions, and when necessary, a referral to a higher and more specialized level of care. Within this context, it is important to understand which actors are related to the identification, care, and follow-up of patients with UAU and the barriers and facilitators that this network of actors could pose to a comprehensive integration strategy for unhealthy drinking within the primary care system.

Actor-Network Theory (ANT)ANT emerged within the field of sociology from Social Science studies carried out by Bruno Latour. According to the theory, an actor is considered “a source of action, regardless of their human or non-human condition”.7 This theoretical framework has been applied to the study of unhealthy use of alcohol and other substances in order to address the complexity of these problems in a comprehensive manner,8–10 and specifically to study the way in which information technology development in healthcare are linked within social networks as an actor.7 With respect to UAU, ANT was used to draw attention to the multitude of actors and forces influencing alcohol consumption, as well as the various scenarios, events or contexts9,10 in which alcohol fulfills different roles. Other studies regarding UAU and sociocultural patterns have been conducted in high-income countries.11–13 However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that applied ANT to understand UAU in rural populations nor in patients living in medium or low-income countries.

ANT also considers that an actor can only act in combination with others, creating constellations in time and specific places, called scenarios. These actors and networks of actors can include objects, ideas, and institutions. The configurations that they produce may or may not be stable over time.

MethodologyThis article comes out of an implementation research project that seeks to apply evidence-based interventions for the detection and treatment of depression and risky alcohol use in primary care settings.14 The first phase included five centers selected from different areas in Colombia to explore the perceptions, abilities, attitudes, practices, and experiences of health professionals, administrative staff, patients, and community organizations on the access, continuity, integration, quality, and resolution of mental health problems in primary care. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committees at involved institutions.

Before the pilot phase, an assessment of the existing local conditions for the care of patients with depression or alcohol use disorders was conducted. In this qualitative assessment characteristics of the HIA were considered as inclusion criteria, which consisted of the following: rural vs urban, the type of institution (private or SOI), the level of care, and the services available (primary care, hospital, specialized hospital). The final inclusion criterion for the participating HIA was the continuity in its interest to participate. Location differences between the selected HIA enabled the recognition of regional or historical differences concerning the provision of health services as well as the socio-cultural relationship with alcohol, which have previously been reported in other studies.15,16

The present study analyses data from such assessment from five sites (See table 1). Semi-structured interviews and FG were conducted with patients, health and administrative staff, and users from Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). The selection of participants was out of convenience, solely considering as inclusion criteria their role in the primary care network (patient, health or administrative staff), and as recruitment criteria their availability and willingness to participate. In all cases, written informed consent was obtained.

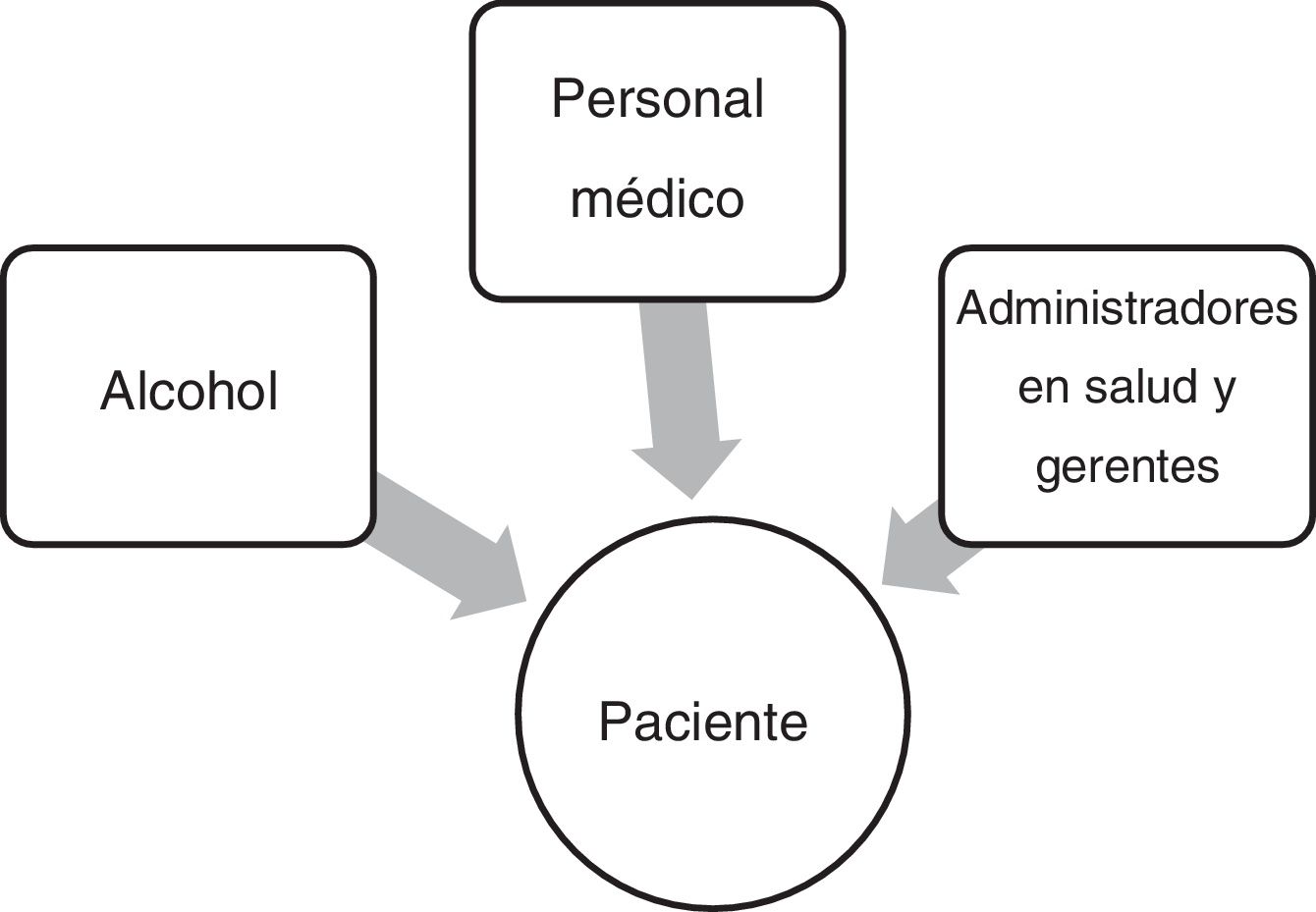

The interviews were transcribed and organized using N-Vivo software in order to apply qualitative analysis based on ANT, including the identification of actors and the way they are distributed in specific scenarios. In order to identify actors, a previously expected actor-network was established consisting of patient, alcohol, doctors, nurses, administrators, and managers, and interviews were initially codified using this actor-network within N-Vivo (see Fig. 1).

Subsequently, through iterative reading17 and coding triangulated by two researchers, other actors were identified and interviews were re-coded. For each of the initially expected actors, a text search query was made in N-Vivo on a broad research setting. Exact matches, words with the same stem and synonyms, were in turn recorded as queries. Later, an analysis of these references and selected segments were conducted. This analysis established the ways in which different actors are linked by the community to UAU, the characteristics and classification of these actors as well as the identification of different contexts and scenarios within which the problem emerges from the perspective and logic of this specific scenario.

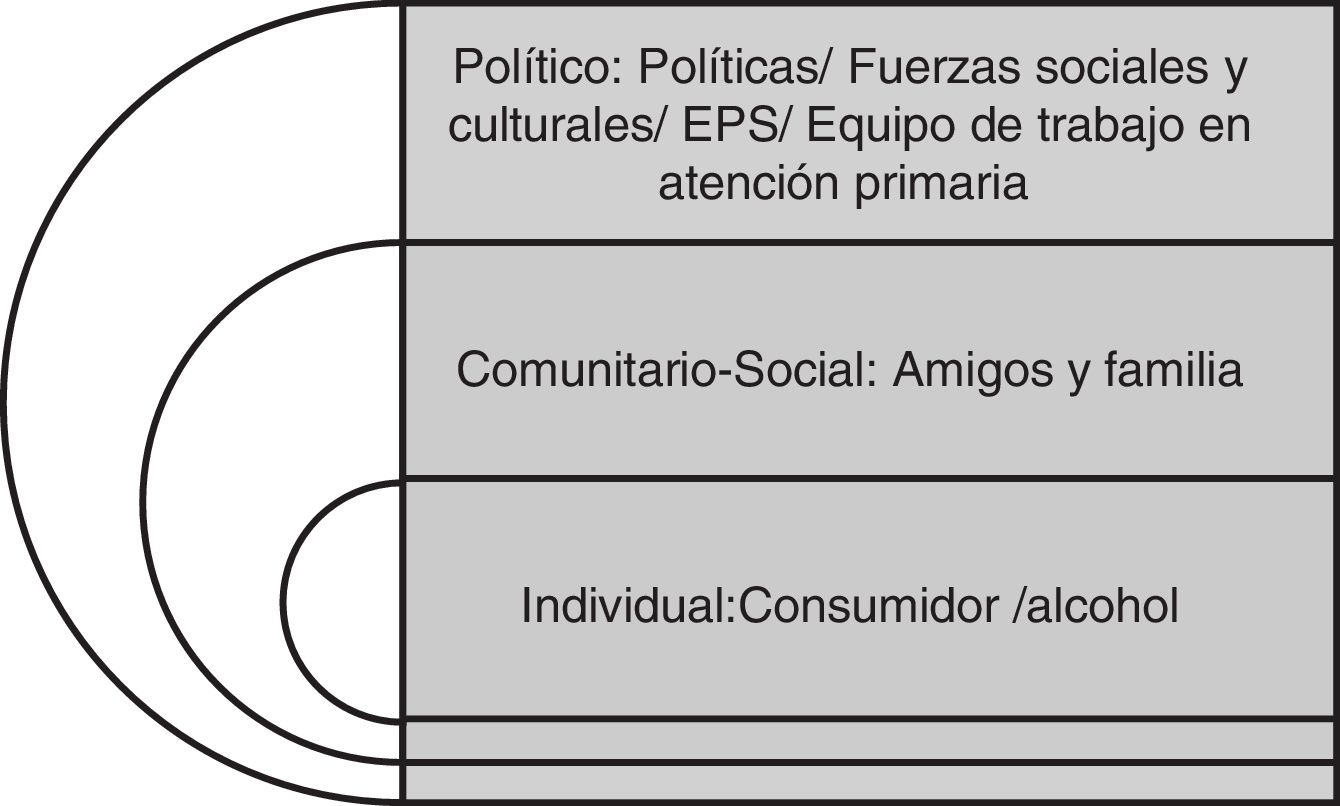

The results of this qualitative approach based on ANT present the actors identified in a non-linear network with three different dimensions: a central dimension around the consumer in relation to alcohol; another dimension that includes close friends and relatives, and a wider dimension, the social and cultural forces, and institutional or political actors. These dimensions are usually considered in sociological and anthropological theory as individual-social and political dimensions,18 and used to describe the way policy is incorporated in social and individual realities and the way a specific object, it's meaning and uses -in this case, alcohol- and its properties emerge from the interaction within the network, and mediate the processes of identification, care and follow-up of UAU (See Fig. 2).

ANT allows for identification of the way in which actors relate to alcohol and the consumer or patient themselves, mediates the identification, care, and follow-up of UAU and produces barriers or facilitators that affect each of these steps. It is important to realize that according to the ANT framework, alcohol is itself considered as an actor. Thus, in the context of this analysis, it is proposed to recognize what is considered as a “problematic alcohol consumption” as changing health target7 at is modified according to local contexts, and whose effects can be interpreted in different ways according to the individual, familial and sociocultural factors.

ResultsMultiple actors were identified as being related to UAU and would be presented according to their distance or relation attributed in the recognition of a consumption problem, or in the search for help or attention within the services. Results will be organized based on alcohol, family and friends, the PHC team, HCPs, Technology, and Actors beyond the health services.

Alcohol as an actorAccording to people interviewed, alcohol is present within “Colombian” social relations and permeates through political relations as well as domestic and familial relations. The consumption and consequences of consumption are widely accepted within the culture, as recognized by an AA member: “(…)you celebrate with alcohol, the norm is to have a list of what you are going to drink or offer to your guests, but you never make a list of the food that you will give them (…). However, for the drinks, there has to be: whiskey for my boss, "aguardiente" for my uncle, beer for my grandfather. We always put alcohol first and that is what we see at the national level, and it is the culture" (FG, AA).

Interviewed individuals referred to alcohol in a specific order of prestige and value: whiskey, rum, beer, "chicha”, and “guarapo”. Drinks such as whiskey and rum are considered fine liquors served at important events and linked to social prestige, associated with celebrations such as birthdays and weddings. Beer is considered a ‘safe alcohol’ that is not associated with adverse effects and can be consumed after physical labor with friends or even when sick. “La chicha” and “El guarapo” are fermented drinks that are generally made from maize and are strongly associated with local production practices and sales with a high socio-cultural value: “Especially in two municipalities, many families still make a living from “la chicha” and “el guarapo” and are dependent on these drinks” (FG, Site 4). Looking at the different types of specific scenarios13 allows us to understand alcohol as an independent actor in the ANT, to the extent that different types of alcohol generate different regional identity processes.

Risky alcohol use is only seen as a concern when serious social or biomedical consequences occur. The acceptability and normality of local alcohol consumption have been highlighted by health professionals and administrative staff as the reason behind the small number of individuals who come in for a consultation, and the difficulty of the community as a whole to recognize UAU as a serious health problem. A doctor relayed, “I have not seen a single patient that has visited me for problems related to alcohol abuse. The patients say, “I have high blood pressure, I have diabetes… I drink alcohol, I drink beer on the weekend, I like to drink, but I do not see the problem with this. If the patient can't even recognize his own body, how can he even try to or say no [to alcohol], it is a problem that is very complex to treat, approach and manage" (FG, Site 2, Doctor)

The family and network of friendsFamily and friends were considered as central to the configuration of the relationship between the alcohol consumer and alcohol, whether this configuration encourages the unhealthy use of alcohol or the search for help. An interviewee says: “This is something that is passed from generation to generation; for example, if I drink it is because my father drank a lot. Why wouldn’t I drink?” (FG, AA).

Family members and especially wives are seen as having the capacity to identify male UAU, to encourage the search for help as well as accompany the patient during the process. A social worker shared that “Diagnosing patients through their family is better than through the excessive consumption of alcohol. When they arrive, we notice older adults that are already in the process of cirrhosis, sometimes the patients aren’t even aware of the problem themselves. If someone asks [if they drink alcohol] they say “no, no, never”. However, there is also what the family tells us, especially the wives, which is that “he drinks many glasses of “chimichan(sic)”, two glasses of “guarapo”, he drinks beer, when he gets out of work he drinks” (Interview, Site 4, health personnel). The wives are also associated with the follow up: “after the wives come and tell us “(…) can you believe doctor, that he had not gone, he did not want to go, he did not come back, he did not like it” he would continue to do the same thing” (Interview, Social Worker, Site 4). Women fulfill the same role in relation to their children who consume alcohol in an unhealthy manner. They are the ones to identify the problem, and most of the time the ones to seek alternative methods of solving the problem even when they are not necessarily successful.

The PHC teamBased on the interviews and FGs, the PHC team is recognized as an interdisciplinary team focused on the identification, care, and follow-up of patients with UAU. This team includes general physicians, mandatory social service physicians, residents, nurses, psychologists, and social workers. Generally, the health personnel is recognized as an actor that is supposed to have the greatest capacity to identify, attend to and ensure the follow up of patients with UAU.

However, physicians, residents, and nurses often consider that UAU and mental health are not problems related to their profession, or that they do not have the appropriate tools to address these problems. The feeling of not knowing what to do is recurrent. Indeed, one of them stated: “(…) it would be wonderful if we were all trained, not only in the diagnosis, as the diagnosis is relatively simple, but also what to do with this patient in primary care” (Focal Group, Health Personnel, Site 1). Another also shared: “It seems to me that I am great at both detection and diagnosis, however when it comes to the treatment and the approach, I am stuck” (FG, Health Personnel, Site 1). This perception includes mandatory social service physicians. During an FG a participant stated that “when the doctors go to provide care, they do not come prepared, we do not have doctors with experience, we only have mandatory social service physicians who come to experiment, to learn, and to finish training, so to speak, with the patients” (FG, Site 3, Administrative staff).

Due to their perceived lack of knowledge, the PHC team tends to place the responsibility for the identification and care for this problem on specific disciplines such as psychologists and social workers, rather than the medical personnel. Despite the existence of several guides that recommend brief interventions and adequate strategies for at-risk drinkers4,15 PHC team feels as they do not have the tools or resources to address de alcohol problem. For example, the limited time available for consultations and the fragmented nature of the follow up of patients makes health personnel reportedly feel a lack of closeness with these individuals and thus impedes their capacity to provide care. This also makes it difficult to identify behaviors associated with the unhealthy use of alcohol: “(…) it is a very impersonal consultation, as the medical personnel does not have time to make a deeper assessment of their patient and thus many things can escape them” (Interview, Administrative Staff, Site 4, 2017).

On the other hand, psychologists and social workers are expected to follow their patients externally and establish a deeper relationship with patients during their treatment, as well as their family during the follow-up of the case. Relationships with physicians are considered exclusively limited to care within HIA.

Service Provider Entities as actors of the General System of Social Security in HealthThe Service Provider Entities (SPE) should be considered as actors of the General System of Social Security in Health (GSSSH), as they administer the resources and distribute the services. In general, health personnel expressed that there is a shortage of resources and specifically of health personnel, problems in the referral of patients, problems in the opportunity for and provision of diagnostic exams, as well as precarious financing of the work conducted by health provider institutions. These problems push patients to demand specialized services that they do not find in PHC: “the user prefers to come to the hospital because they know that they can access all of the complementary services here” (Focal Group, Site 4, Administrative staff).

In addition to this health personnel and administrative staff have noticed other barriers within the health system. During an FG a person stated: "Unfortunately, the authorizations [for follow up consultations] may take a month or two and the other important issue is that of the medications. (…) One month the patient is given medication, the other month they do not deliver it. Thus, there is no continuity with the delivery of medication” (FG, Site 4, Administrative staff).

Another barrier in the care of these patients lies within a lack of agreement amongst institutions that is necessary in order to coordinate referrals to specialized centers or for the provision of a specific type of treatment. An individual in Site 4 stated, “(…) in Boyacá there is nowhere to refer those patients. When we have patients with this type of problem we think about where to send them but it is like a game of ‘hot potato’ as everyone else is also trying to think about what to do with these patients, where to refer them to” (FG, Site 4, Administrative staff).

Use of cellphones and appsWhen asked about the role of cellphones or apps to solve some barriers, participants view it as a secondary tool that did not play a role in the determination of the well-being or health outcomes of the patient. This technology was only seen as a support for these processes (Interview, Specialist, Site 5), specifically for the remote monitoring of patients, and for the encouragement of accompaniment processes. Managers, on the other hand, consider cellphones as an opportunity to connect and prioritize patients, services and primary care doctors: "Because I do not have a sufficient amount of beds to attend to the number of patients that require our services, it would be ideal if doctors at the primary care level could communicate with us and we can tell them, listen it can be done in this way, or manage it in this form or this manner, and we could develop a real idea of the patients that need the service" (Interview, Site 5, Administrative). Based on these interviews, interest in adopting this technology will vary based on perceived need and the perspective of the actors involved. For doctors, apps may be seen as an additional procedure, an imposition, and something that requires time, whereas for managers cellphones and apps may represent a possibility to optimize resources, distribute responsibilities and carry out their responsibilities without having to move.

The main barriers associated with cellphones and apps as actors are the costs, the socio-cultural limitations associated with the age of the user (older individuals might not know how to use smartphones, which the application requires), education in rural areas, and economic resources. A patient in one of the FGs stated in relation to them: "yes, it is interesting, but at least for me, I would not have access to them because, or it is hard for me to even recharge my phone with a thousand pesos in order to call, so there is no way that I would be able to access these applications” (FG, Patients, Site 4).

External actors: beyond health care servicesDuring interviews and FGs, and in addition to the family as a central actor, educational and religious institutions were also identified as key actors in the identification, recognition, and subsequent follow-up of UAU. Churches, priests, and support groups are frequently the first set of actors that are approached when there are issues with alcohol consumption, before seeking health centers.

Despite its broad coverage, AA seems to have a conflicting relationship with HCP, as it is not common for individuals to be referred back to health centers after having been referred to an AA support group. This occurs due to the lack of agreements, bridges, or mechanisms that link the consumer to both actors.

Interestingly, actors such as the sellers or providers of alcohol, bartenders, or actors that determine the local ways in which alcohol is supplied and consumed seem to have no relationship – for the interviewees – with the problematic consumption of alcohol.

In one of the sites, members of the user association of the hospital identified a conflicting relationship between the merchant union (shopkeepers and bars) and promotion and prevention policies of the Municipality that imposed restrictions on the sale and consumption of liquor. According to the Municipality, these regulations appeared as a response to the high levels of alcohol consumption in the region. However, consumers regularly evade these regulations and thus have limited the scope of these strategies.

On the other hand, health personnel and administrative staff believe that technology companies or institutions of higher education have the potential to support the follow-up and recovery of people with alcohol use disorders. These institutions could help strengthen the training of these patients, which would help them increase their chances of finding work in the future as the loss of work and the stigma placed on individuals with problematic alcohol consumption consistently puts them in precarious positions in terms of employment and income. Thus, spreading awareness of this issue to employers is important for the follow-up and future incorporation of these patients into the labor force.

DiscussionUAU can be understood as a form of consumption that increases the probability of negative health outcomes, both for the consumer as well as third parties. In this manner, this concept includes different levels of risk and consumption patterns such as excessive episodic consumption, dangerous or harmful consumption in situations with high levels of risk, or consumption despite physical or psychological conditions that could be aggravated by small amounts of alcohol intake.15 However, in a context in which the consumption of alcohol and its effects are culturally accepted and where the public does not have knowledge of the health risks associated with alcohol, third parties are only capable of identifying the problem when it produces adverse events or violent behaviors. In other words, the relationship between alcohol and the consumer is considered problematic only when a crisis is occurring.

From the ANT perspective, it is possible to conclude that the relationship with alcohol is one in which alcohol is an actor that is highly valued as a social mediator, whose moderate effects are accepted by the majority of the actors, and in which social limits established by context determine the moment as well as the individual who is identified as having a problem with alcohol. For example, in rural areas in Colombia, “la chicha” and “el guarapo" have high socio-cultural and economic value, which is seen as a barrier to the identification and treatment of UAU. If within the dominating social context, the consumption of alcohol is normalized, the identification of UAU is difficult to achieve for health personal, families, or friends.

This cultural relation with both alcohol and interventions is consistent with previous studies in diverse cultural settings.11 This means, in terms of recognition, that only late identification of the problem is achieved. Health personnel believes that the recognition and identification of the consumption of other psychoactive substances are made much more easily and that the positive cultural view of risky alcohol use hinders the strategies used to encourage its moderate consumption. Taking into account what was said by the interviewees and what was highlighted during FGs, alcohol consumption creates a double standard where alcohol is accepted and sanctioned at the same time. In addition, the same double standard applies to the health systems, as alcohol use is seen as a problem but at the same time gives economic benefits through taxes as one to the main funders of the health system.

Although the unhealthy use of alcohol is usually considered a product of the relations between the consumer and alcohol, family and women within these contexts appear to be central actors within the processes of identification and follow up of the problem. Indeed, women are often responsible for scheduling appointments, monitoring medication intake, as well as providing support throughout and encouraging adherence to the treatment process.

Primary care physicians have expressed their lack of tools and capacities for the treatment of UAU, and place the burden of both the care and follow-up of these patients on psychologists and social workers. Although they recognize the importance of a psychiatrist for the care of people with alcohol use disorders, they do not believe that the provision of this resource is feasible within the health system. In this network of actors, the relationship between the general physician and the patient stands out and is the ideal of the primary care system, which places general physicians as close to the patient as possible. However, primary care doctors believe they do not have the tools and capacities necessary for alcohol use interventions. Mandatory social service physicians are perceived as having far fewer tools and training within the health system, despite being the largest and only available human resource in some of the rural and remote areas of the country.

Although the use of structured interviews and FGs representing different stakeholders allows an in-depth description of networks of actors involved in identifying alcohol use problems in primary care, some limitations should be noted. The sample, representing urban and rural settings, does not represent other socio-cultural practices in a country as diverse as Colombia. In addition, people who are less interested in taking part in study groups and thus are not represented in the current study might include some people in more need of care. However, as the current report is part of an ongoing project, data from the implementation of the model of care for alcohol use problems in primary care will complement the analysis of the network of actors described here.

ConclusionTo the extent that family or friends, with the aid of educational and religious institutions, are the first actors to identify the problem, they should be considered central actors in the identification of UAU, and thus may be involved in the processes of screening and technology implementation. In particular, increasing mental health literacy and patient participation at the primary care level are needed as key strategies in order to achieve better detection of alcohol risky use.

Currently, consumers typically do not use health services for the identification and diagnosis of alcohol use disorders. They only consult health services once their use has caused them excessive harm or harm to third parties. This inevitably leads to the late identification of people with alcohol use difficulties. Nevertheless, this represents a starting point for PHC facilities and increasing patient literacy and participation could be an important step towards greater awareness and identification of alcohol risks.

Technologies that support the diagnosis. Care and follow-up of patients should consider the different and varying local uses of alcohol. It is necessary for Colombia to further explore the variations in the relationship with alcohol across the country and how new products and forms of consumption are being established within remote and rural areas.

The administrative and bureaucratic procedures necessary to enable access to and organize appointments for treatment and follow-up are barriers to the continuity of care and the adherence to treatments for people with alcohol use disorders and, more generally, all mental health disorders. Likewise, delays in the delivery of medication for respective treatments also have an impact on the continuity of care of patients, as well as the transportation costs incurred by patients who live in rural or distant zones relative to HIA in order to access treatment and follow-up procedures.

Routine screening for UAU, educational material for those who screen positive and defined care pathways could establish alcohol use as a core routine health concern within primary care. This will provide education and normalize the discussion of alcohol for the patient, the social network, and the HCP and make it easier for people who are privately worried about their alcohol use to seek help. Education, practice support, and experience will help primary care doctors feel more confident and capable in this domain of their work. However, this routine screening procedures need to be complemented with health system-wide interventions in order to be successful.

Based on this scenario, the development of technology (mobile applications) emerges as an opportunity to improve the deficits that exist in the processes of identification and care for mental health and harmful alcohol use patients. It will be important to identify the different motivations and values that actors attribute to these technologies, as some actors may view them as an important opportunity while others may simply view them as a supplement to other more structured interventions. Patients with limited access to the use of mobile technology because they live in rural areas or are in precarious economic situations, represent barriers to the implementation of the technology.

FundingResearch reported in this publication was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number 1U19MH109988 (Multiple Principal Investigators: Lisa A. Marsch, Ph.D. and Carlos Gómez-Restrepo, MD). The contents are solely the opinion of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or the United States Government.

Conflict of interestDr. Lisa Marsch, one of the principal investigators on this project, is affiliated with the business that developed the mobile intervention platform that is being used in this research. This relationship is extensively managed by Dr. Marsch and her academic institution.

Please cite this article as: Medina Ch. AM, Torrey WC, Varga S, Uribe-Restrepo JM, Gómez-Restrepo C. Red de actores involucrados en la identificación, cuidado y seguimiento del uso nocivo de alcohol en atención primaria en Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:83–90.