Colombia passed Law 100 in 1993 with the goal of providing universal health care coverage, and by 2013, over 96% of the Colombian population had health insurance coverage. However, little is known about how health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and health literacy are related among those with the two most common types of health insurance coverage: subsidized (those with lower incomes) and contributory (those with higher incomes) coverage.

Objectives and methodsIn the current exploratory investigation, data from adults visiting six primary care clinics in Colombia were analysed to examine the relationship between HRQoL (assessed as problems with mobility, self-care, completing usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), demographics, the two health insurance types, and health literacy. Analyses also assessed whether, within insurance types, health literacy was related to HRQoL.

ResultsResults showed that those with contributory health insurance coverage had greater health literacy than those with subsidized coverage, and this was accounted for by differences in education and socioeconomic status. HRQoL did not differ by insurance type. Although lower health literacy was related to worse HRQoL in the overall sample, in subgroup analyses lower health literacy significantly related to worse HRQoL only among those with subsidized health insurance coverage.

ConclusionTargeting skills which contribute to health literacy, such as interpreting medical information or filling out forms, may improve HRQoL, particularly in those with subsidized insurance coverage.

Colombia emitió la Ley 100 en 1993 con el objetivo de proveer un cubrimiento de salud para toda la población, y para el año 2013, más del 96% de la población colombiana tenía cubrimiento en salud. No obstante, es poca la evidencia sobre como la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) y la alfabetización en salud se relacionan con la vinculación de las personas a los dos regímenes más predominantes en el sistema de salud colombiano: el régimen subsidiado (para personas con bajos ingresos) y el régimen contributivo (para personas con mayores ingresos).

Objetivos y métodosEn esta investigación, se analizaron datos de adultos que acudieron a seis centros de atención primaria en salud en Colombia con el fin de determinar la relación entre CVRS (evaluada a través de componentes como problemas de movilidad, autocuidado, realización de actividades usuales, dolor/disconfort y ansiedad/depresión), factores sociodemográficos, tipo de afiliación al régimen de salud y alfabetización en salud.

ResultadosLos resultados mostraron que las personas afiliadas al régimen contributivo tenían mayor alfabetización en salud que aquellas afiliadas al régimen subsidiado, lo cual se puede explicar por diferencias a nivel educativo y estatus socioeconómico. Para CVRS no hubo diferencias en cuanto a tipo de régimen en salud. Aunque una menor alfabetización en salud se vio relacionada con peor CVRS en la muestra general, en análisis de subgrupos solo se mantuvo esta tendencia en el grupo de personas con régimen de salud subsidiado.

ConclusionesEl enfoque en habilidades que determinan parte de la alfabetización en salud, como interpretación de información médica o llenar cuestionarios, puede mejorar la CVRS, particularmente en las personas afiliadas al régimen subsidiado.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL), a person’s perceived level of health and the extent to which physical and mental health are compromised in daily life,1 has been promoted as a key outcome for evaluating and informing doctor-patient relationships, medical treatments, and health care policy by the World Health Organization’s (WHO).2 Despite the relevance of HRQoL to health care and health systems, much of what is known about HRQoL comes from research in high income countries (HICs; e.g.3), and there is relatively little research evaluating HRQoL among people in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).4–6 In LMICs, demographic and socioeconomic variables are also associated with HRQoL. HRQoL tends to be worse for those with chronic disease, disability, or greater BMI.7–9 Employment,9,10 higher income,7–9 and greater educational attainment7–10 are associated with better HRQoL, whereas being female7 or of higher age7–9,11 are associated with worse HRQoL. In addition, although health systems vary across LMICs,12 preliminary research suggests that having health insurance is associated with better HRQoL.8,10

Colombia has made strides towards improving the health of its population through changes to its health insurance system, but few studies have evaluated differences in HRQoL based on this insurance system. Colombia passed Law 100 in 199313 with the aim of providing universal health insurance coverage for its citizens. By 2013, 96% of the population had health insurance, most through either the subsidized or contributive system.14,15 More than half of Colombians are covered by the subsidized system, which insures the unemployed, poor, or informally employed.14 By contrast, the contributive system provides health insurance coverage to those with formal employment or the capacity to pay. The contributive system is typically financed by the employee and their employer through payroll contributions, whereas insurance in the subsidized system is funded mostly through general taxation.14 Regardless of insurance system, all Colombians are entitled to the same comprehensive care package.16 This funding structure serves a redistributive function and overcomes financial barriers to health care. Relative to healthcare access before Law 100, this insurance system has improved health care utilization, including ambulatory medical services, in-patient hospital services, and medication consumption, although those in the contributive system still have greater access over those in the subsidized system.17,18

Recent research has evaluated HRQoL in Colombia, replicating findings that lower HRQoL is associated with female sex,19–21 higher age19,20 and having a chronic disease.22 Although Colombia is currently grappling with marked income inequality,23 income has been inconsistently related to HRQoL among Colombians.21 Such income inequality may also be a proxy for education inequality, and lower educational attainment has been associated with lower HRQoL among Colombians.24 To our knowledge, the only study of health insurance and HRQoL in Colombia found that among adults in Barranquilla, a city located on the north-western coast of Colombia, those with subsidized insurance reported fair or poor health more often than those with contributory insurance.19

Other variables impact HRQoL in LIMCs.25–27 Health literacy—the set of skills “needed to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health”28—has been associated with worse health outcomes, such as more hospitalizations, less utilization of preventative services, and greater use of emergency care.29 Further, better HRQoL is associated with better health literacy among patients with chronic diseases,27 whereas worse HRQoL is associated with low health literacy among general/healthy samples,25,26 though some research suggests this effect may be tempered by educational attainment.30 Health literacy is influenced by education and socioeconomic status (SES), but health literacy has also been shown to mediate the relation between SES and health outcomes and quality of life.31 Limited research has evaluated health literacy, health insurance, and HRQoL, but findings from Ghana show that health insurance coverage is positively associated with HRQoL only for those with high health literacy.26 To our knowledge, no studies have evaluated the impact of health literacy on HRQoL in Colombia or evaluated whether health literacy differs by type of insurance.

The goal of this study was to examine the effects of health insurance and health literacy on HRQoL in Colombia. This study evaluated HRQoL and health literacy among adults visiting one of six primary care clinics in Colombia. Relations between HRQoL, demographic variables, and health literacy were examined overall and separately for subgroups split by insurance type.

MethodProcedureThis study was part of formative work for a project on “Scaling up Science-based Mental Health Interventions in Latin America” (DIADA project: Detección y atención integrada de la depresión y uso de alcohol en atención primaria). The DIADA project is developing and evaluating a system for embedding mental health services in primary care in Latin America. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Javeriana University and Dartmouth College. Participants provided informed consent and then completed a survey programmed in REDCap that was self-administered on a tablet in the waiting room of the clinic where they were recruited.32 Use of the REDCap application permitted researchers to confidentially collect data offline in areas with intermittent internet access, but data were uploaded daily.

ParticipantsParticipants were 1580 adult patients (≥18 years of age) recruited from the waiting rooms of six primary care clinics in Colombia for a survey on health and technology use (see Ref. 33 for more details). To recruit a more representative sample, public and private clinics served as recruitment sites, and the clinics were located in urban, suburban, or rural settings:

- •

Clinic 1 was a private ambulatory health center in the capital and largest city, Bogotá (population of approximately 9 million). Clinic 1 provided patient-centered primary care within a family-medicine framework for primarily urban patients.

- •

Clinic 2 was a public clinic in a small town (population of approximately 11,000) that offered ambulatory services (i.e., outpatient, emergency care, and ambulance transportation) for approximately 14,000 people, 47% of whom live in rural areas.

- •

Clinic 3 was a public primary care center serving urban, suburban, and rural populations in a moderate-sized city (population of approximately 110,000).

- •

Clinic 4 was a public hospital offering specialized psychiatric services for patients from its small town (population of approximately 17,000) and surrounding rural areas.

- •

Clinic 5 was a public primary care center located in a small town (population of approximately 11,000). Clinic 5 provided primary care and ambulatory, emergency, and short stay hospitalization services for inhabitants of the town and surrounding rural areas.

- •

Clinic 6 was a public primary care center in a small city (population of approximately 47,000). Clinic 6 served patients from the city and surrounding rural areas.

Only those (n = 1,481, 93.7%) who provided complete data and reported health insurance under either the contributive (n = 615) or subsidized (n = 866) systems were included in the current analyses. A total of 95 participants reported other types of health insurance, one participant did not report socioeconomic strata, and three participants did not complete either the HRQoL or health literacy measures.

MeasuresThe survey included items assessing demographics (e.g., age, sex, education, socioeconomic strata, health insurance type), technology use (not reported; see Ref. 33), HRQoL, and health literacy.

HRQoLParticipants completed the EQ-5D-3L,34 an assessment of HRQoL validated in South American but not specifically in Colombia. Participants rated their health today across five domains: mobility, self-care, daily activities, pain, anxiety and depression. For each domain, participants could endorse no problems, moderate problems, or severe problems. The ratings across domains were combined into five-digit profiles reflecting individuals’ health states. For analysis, these profiles were assigned overall index scores based on regional preference weights for the health state profiles derived from visual analog scale ratings of health value collected in Argentina.35 Ratings for reporting problems within each domain were dichotomized as either no problems or some problems (i.e., ratings of moderate and severe problems were combined).

Health literacyHealth literacy was evaluated with a three-item assessment validated in Spanish but not specifically with a Colombian population.36 Participants responded to three questions using a five-point Likert scale: (1) "How confident are you filling out medical forms?"; (2) "How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information?"; (3) "How often do you have someone help you read hospital materials?" The confidence with forms question was scored from 1 = Extremely confident to 5 = Not at all confident. The remaining two questions were scored such that 1 = Never to 5 = Always. Responses were summed to calculate a score ranging from 3 to 15 with higher scores indicating lower health literacy.

AnalysisDemographic characteristics, health literacy, and HRQoL were compared for those with contributive relative to subsidized insurance coverage using t-tests for interval data and chi-square tests for categorical data. Additionally, to evaluate differences in health literacy after accounting for education and SES, an ANCOVA was conducted comparing health literacy between those with subsidized and contributive health insurance with education and socioeconomic strata entered as covariates.

A hierarchical regression model was developed to evaluate the relative contribution of demographic variables and health literacy to HRQoL for the overall sample. In the first step, sex, age, ethnicity (coded as mestizo relative to other race/ethnicity), marital status (coded as whether participants were married/cohabitating or not), employment status (coded as full-time, part-time, and self-employed relative to not employed), education (coded as whether participants had completed at least secondary school relative to less education), low socioeconomic status (coded as rural, level 1, and level 2 relative to other socioeconomic strata), and insurance type were entered as predictors of HRQoL. In step 2, health literacy was added to evaluate its impact on HRQoL. To determine specific contributors to HRQoL by insurance type, hierarchical regression models were then developed separately for subgroups with subsidized insurance and contributive insurance. These models included sex, age, ethnicity, marital status, employment status, education, and low socioeconomic status in step 1 and then added health literacy in step 2.

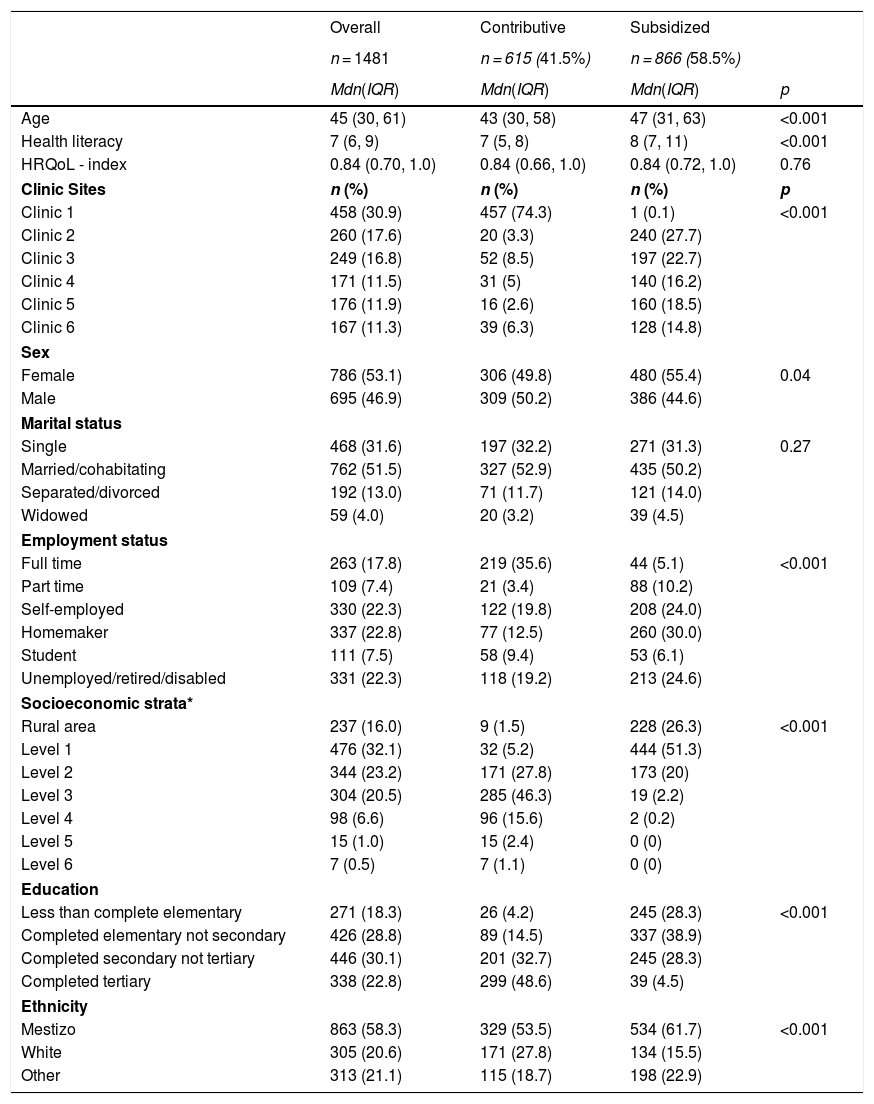

ResultsParticipants’ median age was 45 years (IQR = 30, 61), and 53.1% (n = 786) were women (see Table 1). More than half the sample identified as mestizo (mixed European and Amerindian ancestry37; 58.3%, n = 863), while 20.6% identified as white (n = 305) and 21.1% identified as another racial/ethnic group (n = 313; e.g., Indigenous, Black/Afro-Colombian). More than half the sample (58.5%) had subsidized health insurance, while 41.5% had contributive health insurance. Participants with subsidized health insurance differed from those with contributive health insurance on clinic of recruitment, sex, employment status, socioeconomic strata, education, and ethnicity (all p < 0.04, see Table 1) but not marital status (p = 0.27).

Participant characteristics.

| Overall | Contributive | Subsidized | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1481 | n = 615 (41.5%) | n = 866 (58.5%) | ||

| Mdn(IQR) | Mdn(IQR) | Mdn(IQR) | p | |

| Age | 45 (30, 61) | 43 (30, 58) | 47 (31, 63) | <0.001 |

| Health literacy | 7 (6, 9) | 7 (5, 8) | 8 (7, 11) | <0.001 |

| HRQoL - index | 0.84 (0.70, 1.0) | 0.84 (0.66, 1.0) | 0.84 (0.72, 1.0) | 0.76 |

| Clinic Sites | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p |

| Clinic 1 | 458 (30.9) | 457 (74.3) | 1 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Clinic 2 | 260 (17.6) | 20 (3.3) | 240 (27.7) | |

| Clinic 3 | 249 (16.8) | 52 (8.5) | 197 (22.7) | |

| Clinic 4 | 171 (11.5) | 31 (5) | 140 (16.2) | |

| Clinic 5 | 176 (11.9) | 16 (2.6) | 160 (18.5) | |

| Clinic 6 | 167 (11.3) | 39 (6.3) | 128 (14.8) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 786 (53.1) | 306 (49.8) | 480 (55.4) | 0.04 |

| Male | 695 (46.9) | 309 (50.2) | 386 (44.6) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 468 (31.6) | 197 (32.2) | 271 (31.3) | 0.27 |

| Married/cohabitating | 762 (51.5) | 327 (52.9) | 435 (50.2) | |

| Separated/divorced | 192 (13.0) | 71 (11.7) | 121 (14.0) | |

| Widowed | 59 (4.0) | 20 (3.2) | 39 (4.5) | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full time | 263 (17.8) | 219 (35.6) | 44 (5.1) | <0.001 |

| Part time | 109 (7.4) | 21 (3.4) | 88 (10.2) | |

| Self-employed | 330 (22.3) | 122 (19.8) | 208 (24.0) | |

| Homemaker | 337 (22.8) | 77 (12.5) | 260 (30.0) | |

| Student | 111 (7.5) | 58 (9.4) | 53 (6.1) | |

| Unemployed/retired/disabled | 331 (22.3) | 118 (19.2) | 213 (24.6) | |

| Socioeconomic strata* | ||||

| Rural area | 237 (16.0) | 9 (1.5) | 228 (26.3) | <0.001 |

| Level 1 | 476 (32.1) | 32 (5.2) | 444 (51.3) | |

| Level 2 | 344 (23.2) | 171 (27.8) | 173 (20) | |

| Level 3 | 304 (20.5) | 285 (46.3) | 19 (2.2) | |

| Level 4 | 98 (6.6) | 96 (15.6) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Level 5 | 15 (1.0) | 15 (2.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Level 6 | 7 (0.5) | 7 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Education | ||||

| Less than complete elementary | 271 (18.3) | 26 (4.2) | 245 (28.3) | <0.001 |

| Completed elementary not secondary | 426 (28.8) | 89 (14.5) | 337 (38.9) | |

| Completed secondary not tertiary | 446 (30.1) | 201 (32.7) | 245 (28.3) | |

| Completed tertiary | 338 (22.8) | 299 (48.6) | 39 (4.5) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Mestizo | 863 (58.3) | 329 (53.5) | 534 (61.7) | <0.001 |

| White | 305 (20.6) | 171 (27.8) | 134 (15.5) | |

| Other | 313 (21.1) | 115 (18.7) | 198 (22.9) | |

The median HRQoL index score (scored 0.0–1.0) for the sample was .84 (IQR = 0.70, 1.0), and HRQoL did not differ between those with contributive relative to subsidized health insurance coverage (p = 0.76). In the overall sample, 18% reported some or extreme problems with their mobility, 4.2% reported some or extreme problems with self-care, 14.8% reported some or extreme problems with daily activities, 41.3% reported some or extreme problems with pain, and 22.8% reported some or extreme problems with anxiety/depression. None of these categories of HRQoL differed between those with subsidized relative to contributive insurance (all p > 0.10). A t-test revealed that participants with subsidized health insurance had lower health literacy (p < 0.001), though this difference was no longer significant (p = 0.38) after education (p < 0.001) and socioeconomic strata were entered as covariates (p < 0.01).

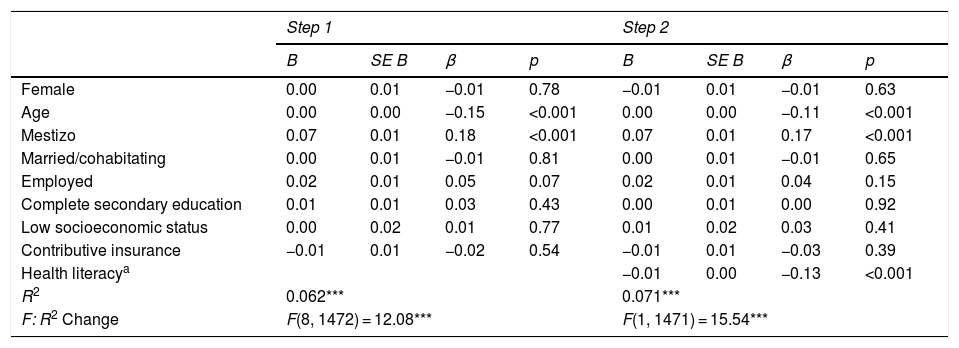

Health quality, demographics, and health literacyFor the overall sample, the hierarchical multiple linear regression model revealed several significant associations with HRQoL in step 1 (F(8, 1472) = 12.08, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.06; see Table 2). Specifically, younger age and mestizo ethnicity were associated with higher HRQoL. Adding health literacy in step 2 significantly improved the model (F(1, 1471) = 15.54, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.07) but did not change any of the significant associations from step 1. Better health literacy was significantly associated with better HRQoL (p < 0.001).

Regression model: HRQoL for the overall sample.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | p | B | SE B | β | p | |

| Female | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.78 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.63 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.15 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.11 | <0.001 |

| Mestizo | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.18 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| Married/cohabitating | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.81 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.65 |

| Employed | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| Complete secondary education | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.92 |

| Low socioeconomic status | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.77 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.41 |

| Contributive insurance | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.54 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.39 |

| Health literacya | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.13 | <0.001 | ||||

| R2 | 0.062*** | 0.071*** | ||||||

| F: R2 Change | F(8, 1472) = 12.08*** | F(1, 1471) = 15.54*** | ||||||

a: Higher health literacy scores indicate worse health literacy.

For those with contributive health insurance, step 1 of the hierarchical regression model produced a significant model (F(7, 607) = 2.13, p = 0.04, R2 = 0.02; see Table 3) and significant associations with HRQoL. Identifying as mestizo relative to other ethnicities was associated with higher HRQoL. Adding health literacy in step 2 did not significantly improve the model (F(1, 606) = 2.98, p = 0.109, R2 = 0.03), though the overall model remained significant (p = 0.02). Health literacy was not significantly associated with HRQoL for those with contributive insurance (p = 0.09), and mestizo ethnicity remained significantly associated with higher HRQoL (p = 0.01).

Regression model: HRQoL for the contributive system.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | p | B | SE B | β | p | |

| Female | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.74 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.70 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.14 |

| Mestizo | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| Married/cohabitating | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.80 |

| Employment | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.85 |

| Complete secondary education | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.29 |

| Low socioeconomic status | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.25 |

| Health literacya | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.08 | ||||

| R2 | 0.024* | 0.029* | ||||||

| F: R2 Change | F(7, 607) = 2.13 | F(1, 606) = 2.98 | ||||||

a: Higher health literacy scores indicate worse health literacy.

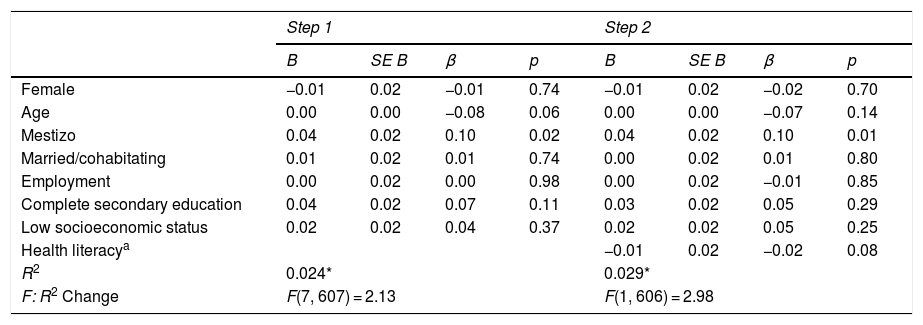

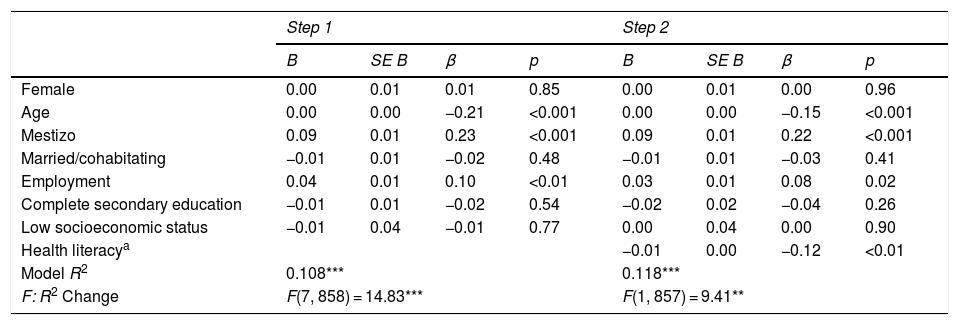

For participants with subsidized insurance, the hierarchical regression model was significant in step 1 (F(7, 858) = 14.83, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.11; see Table 4). Significant associations with higher HRQoL in step 1 included younger age, being mestizo relative to other ethnicities, and being employed. Adding health literacy in step 2 significantly improved the model (F(1, 857) = 9.41, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.12), and health literacy was significantly associated with HRQoL (p < 0.01).

Regression model: HRQoL for the subsidized system.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | p | B | SE B | β | p | |

| Female | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.96 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.21 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.15 | <0.001 |

| Mestizo | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.22 | <0.001 |

| Married/cohabitating | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.48 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.41 |

| Employment | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.10 | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Complete secondary education | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.54 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.26 |

| Low socioeconomic status | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| Health literacya | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.12 | <0.01 | ||||

| Model R2 | 0.108*** | 0.118*** | ||||||

| F: R2 Change | F(7, 858) = 14.83*** | F(1, 857) = 9.41** | ||||||

a: Higher health literacy scores indicate worse health literacy.

Worse health literacy was associated with worse HRQoL for the overall sample, which extends results from other LMICs (e.g., China, Ghana, and Uruguay26,27,30) to Colombia. Further, greater health literacy significantly impacted HRQoL after accounting for demographic variables. When examining associations separately for health insurance subgroups, worse health literacy was significantly associated with worse HRQoL only among those with subsidized health insurance coverage. Health literacy was lower in the subsidized insurance group, but this difference was no longer significant after adjusting for education and SES, suggesting that these variables more strongly accounted for the differences in health literacy. Findings from this study indicate that reducing barriers to accessing health information may be beneficial for improving HRQoL of primary care patients in Colombia. These data also suggest that future research might benefit from examining whether those with subsidized insurance benefit more than those with contributive insurance from interventions that target skills associated with accessing and using health information (i.e., learning about medical conditions, reading hospital materials, filling out forms). In HICs, modifications—such as presenting only essential health information—can improve health outcomes for individuals with low health literacy.38 Further, preliminary findings suggest health literacy interventions may result in HRQoL improvements among individuals with chronic diseases.39

Consistent with prior research, greater age was associated with lower HRQoL overall and in the subsidized insurance group.19,20,40 Further, individuals who identified as mestizo—the largest ethnic group in Colombia—reported greater HRQoL relative to other ethnic groups. To our knowledge, no studies have reported differences in HRQoL by ethnic group in Colombia. Unlike prior research, however, HRQoL in this sample did not differ by sex or insurance type. The findings from the current study may have differed from previous research because the sample was recruited from primary care rather than the population, so included only healthcare seekers. This sample also included more women and used a continuous, rather than categorical, measure of HRQoL,19,20 which also may have impacted findings.

Limitations of the current study could be addressed by future research. First, this study used a self-reported measure of health literacy that was validated in Spanish but has not been validated with a Colombian sample, which may limit its utility given potential regional differences in culture or dialect. Similarly, although the EQ-5D-3L has been used to measure HRQoL among Colombians,20 benchmarks for Colombia are not available for determining the index score so regional (Argentinian) utility values were used. Future research might validate these measures with a Colombian sample. The sample for the current study was recruited from primary care clinics that typically serve low-complexity conditions, though the specific clinical status of the patients was not known. Results from this population may lack generality to the broader Colombian population. Although HRQoL ratings in this sample were similar in level to those found among the broader population,20 future research could recruit a more representative sample. Finally, the insurance subgroups differed on most demographic variables. Several of these were entered into the regression models, but some variables (e.g., clinic) were not included in the models because they were imbalanced between insurance subgroups.

In conclusion, better health literacy was significantly associated with better HRQoL in a large sample of Colombian adults recruited from primary care clinics in Colombia. Although HRQoL did not differ for those with contributive versus subsidized insurance, better health literacy was associated with better HRQoL for those in the subsidized health insurance system. Future research is needed to examine whether interventions that address skills comprising health literacy related to accessing and using health information improve HRQoL in Colombians, particularly for those in the subsidized health insurance system. These results suggest that interventions addressing skills comprising health literacy related to navigating and accessing health information may be important for improving HRQoL, particularly for those in the subsidized health insurance system. Public policy or community health education efforts that target presenting health information in a more understandable fashion may also help attenuate differences in HRQoL associated with health literacy.

FundingThe investigation reported in this publication was financed by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) via Grant# 1U19MH109988 (Multiple Principal Investigators: Lisa A. Marsch, PhD and Carlos Gómez-Restrepo, MD PhD). The content of this article is only the opinion of the authors and does not reflect the viewpoints of the NIH or the Government of the United States of America.

Conflicts of interestAuthors report not having any conflicts of interest. Dr. Lisa A. Marsch, one of the principal investigators on this project, is affiliated with the business that developed the mobile intervention platform that is being used in this research. This relationship is extensively managed by Dr. Marsch and her academic institution.

☆Please cite this article as: Lemley SM, Castro-Diaz S, Cubillos L, Suárez-Obando F, Torrey WC, Uribe-Restrepo JM, et al. Calidad de vida relacionada a salud y alfabetización en salud en pacientes adultos en centros de atención primaria con afiliación al régimen subsidiado o contributivo en Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:22–29.