Huntington's disease (HD) is a neurodegenerative and hereditary disorder. Due to the predictive diagnosis, incipient clinical characteristics have been described in the prodromal phase. Several studies have reported an increase in psychiatric symptoms in carriers of the HD gene without motor symptoms.

ObjectiveTo identify psychological distress in carriers of the mutation that causes HD, without motor symptoms, utilizing the Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90), and to correlate with the burden and proximity of the disease.

MethodA sample of 175 participants in a HD Predictive Diagnostic Program (PDP-HD) was divided into HEP carriers (39.4%) and NPEH non-carriers (61.6%) of the HD-causing mutation. By means of mathematical formulas, the disease burden and proximity to the manifest stage in the PEH group were obtained and it was correlated with the results of the SCL-90-R.

ResultsComparing the results obtained in the SCL-90-R of the PEH and NPEH, the difference is observed in the positive somatic male index, where the PEH obtains higher average scores. The correlations between disease burden and psychological distress occur in the domains; obsessions and compulsions, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility, global severity index and positive somatic distress index. A low correlation is observed between the burden of disease and the scores obtained in psychological discomfort.

ConclusionsIn general, we found that the PEH group obtained a higher score in the dimensions evaluated with the SCL-90-R, showing a relationship with the burden and differences due to the proximity of the disease. Higher scores on the SCL-90-R dimensions in carriers of the HD gene may suggest an early finding of psychological symptoms in the disease.

La enfermedad de Huntington (EH) es un trastorno neurodegenerativo y hereditario, a partir del diagnóstico predictivo se han descrito características clínicas incipientes en la fase prodrómica, varios estudios han reportado aumento de síntomas psiquiátricos en portadores de la mutación causante de la EH, sin síntomas motores, en esta fase.

ObjetivoIdentificar malestar psicológico en portadores de la mutación causante de la EH sin síntomas motores, mediante el SCL-90, y correlacionar con la carga y cercanía de la enfermedad.

MétodoUna muestra de 175 participantes de un Programa de Diagnóstico Predictivo de EH (PDP-EH) se dividió en portadores PEH (39.4%) y no portadores NPEH (61.6%) de la mutación causante de EH. Mediante fórmulas matemáticas se obtuvo la carga de enfermedad y cercanía a la etapa manifiesta en el grupo PEH y se correlacionó con los resultados de inventario SCL-90-R.

ResultadosAl comparar los resultados obtenidos en el SCL-90-R de los PEH y NPEH, la diferencia se observa en el índice de malestar por síntomas positivos, donde los portadores obtienen mayor puntuación promedio. Las correlaciones entre carga de enfermedad y síntomas psicológicos se dan en los dominios; obsesiones y compulsiones, sensibilidad interpersonal, hostilidad, índice de severidad global e índice de malestar somático positivo. Se observa una correlación baja entre la carga de enfermedad y las puntuaciones obtenidas en el malestar psicológico.

ConclusionesEn general encontramos que el grupo PEH obtiene puntaje mayor en las dimensiones evaluadas con el SCL-90, muestran relación con la carga y diferencias por la cercanía de la enfermedad. Puntajes mayores en las dimensiones del SCL-90-R en portadores del gen para la EH pueden sugerir un hallazgo temprano de la sintomatología psicológica en la enfermedad.

Huntington disease (HD) is a neurodegenerative disorder with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Molecular diagnosis is established by quantifying the number of CAG triplet repeats. CAG repeat lengths of fewer than 27 repeats are considered normal; mutations with between 27 and 35 repeats are considered non-penetrant, between 36 and 39 are considered to present reduced penetrance, and > 40 are defined as complete penetrance.1,2

HD manifests in adulthood, presenting with motor, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms. Clinical diagnosis is based on the presence of motor symptoms, including chorea, rigidity, and bradykinesia. Cognitive changes are characterised by progressive difficulties in learning, attention, and executive functions, which may lead to symptoms of dementia.3 The most frequently reported psychiatric manifestations include depression, irritability, apathy, perseveration, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and occasionally psychosis.4

Psychiatric symptoms are a relevant aspect of HD; their manifestation and progression are variable due to the differential degeneration of striato-cortical circuits, and their course does not correlate with progression of motor or cognitive symptoms, with the exception of apathy.5,6 They may present at different stages of the disease, often in atypical forms, even 20 years before the onset of motor manifestations.7

Epping et al.8 found that the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in patients with prodromal HD is the same as in the general population. Although there is an association between the number of CAG repeats and the age of onset of HD, this explains only 60% of variance. Even when environmental factors are taken into account, this does not question the underlying genetic variation, nor has an association with the severity of psychological or psychiatric manifestations been identified.

Several studies have analysed the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in carriers of the HD mutation, reporting an increase in these symptoms in prodromal HD.9–12 The PREDICT-HD research group13 analysed mood and affective disorders (depression, hopelessness, and emotional distress) using self-reported assessments completed by the informant, finding that the average improvement in psychological distress was greater among carriers of the HD mutation than in non-carriers.14,15 These authors also suggest that levels of distress are positively associated with motor scores; therefore, patients with probable HD without motor symptoms tend to be more emotionally stable than those with motor symptoms.15

Thanks to predictive testing for HD and to the analysis of disease burden and proximity to onset, the initial clinical symptoms manifesting in the prodromal phase have been described and clinical markers have been proposed. Likewise, it has been possible to study the development over time of clinical manifestations, including psychiatric manifestations. By psychiatric manifestations, we refer to emotional, behavioural, psychological, and psychiatric symptoms.

In this study, we used the Symptom Check List-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), created by Derogatis,16 to describe and analyse psychological distress among carriers (without motor symptoms) and non-carriers. Our hypothesis is that some specific dimensions of the SCL-90-R will enable us to identify psychological manifestations in carriers presenting no motor symptoms. We also report that those manifestations are associated with disease burden and proximity to onset.

Material and methodsThe genetics department of the Instituto Nacional de Neurología y Neurocirugía Manuel Velasco Suárez (INNNMVS) invites individuals at risk of developing HD to participate in a Huntington disease predictive testing programme (HDPTP),17 as recommended by the International Huntington Association and the World Federation of Neurology’s Research Group on Huntington’s Chorea.18 The HDPTP is approved by the research and ethics committees of the INNNMVS.

The HDPTP first offers genetic counselling, requests verbal and written informed consent19 (for assessments and blood drawing), performs clinical assessments (neurological, neuropsychological, and psychiatric), and subsequently collects blood samples to finally conduct the genetic analysis.

We analysed data from 175 HDPTP participants from the 2002–2019 period who met the following inclusion criteria: age > 18 years, family history of confirmed HD (with molecular diagnosis), not being pregnant, and freely choosing to participate. We excluded patients who did not consent to participate or who did not complete all phases of the programme.

We applied the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS) and, as part of the neuropsychological evaluation, used the Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE),20 the Beck Anxiety and Depression Inventory,21,22 and the SCL-90-R16 to assess psychiatric symptoms.

The revised Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-IA)21 assesses the presence of symptoms of depression in the week before the self-reported assessment; it includes 21 items. The severity score ranges from 0 to 63, and the scale presents good internal consistency (α = .87). The respective cut-off scores for severe depression and anxiety were 31 points or more on each Beck inventory. The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)22 includes 21 items that assess the presence of symptoms of anxiety in the previous week. Scores range from 0 to 63, and the scale presents good internal consistency (α = .911).

The SCL-90-R is a self-administered tool to assess the degree of psychological distress experienced by the respondent. We used the version validated in a Mexican population, which includes a list of 90 psychiatric symptoms with several levels of severity; the informant is asked to indicate the level of disturbance experienced due to each symptom over the 7 days prior to assessment. The scale includes 5 possible answers: not at all, a little bit, moderately, quite a bit, and extremely; score ranges from 0 to 4 points. Using this score, symptoms are classified into 9 primary dimensions (somatisation, obsessive-compulsive disorder, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism). We also used 3 global indexes of psychiatric disorders: the Global Severity Index (GSI); the Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI), which assesses the style of response, detecting tendencies to minimise or exaggerate distress; and the Positive Symptom Total (PST).

Data management and statistical analysisThe results obtained in the different assessments of the HDPTP were recorded in a database using the SPSS software (version 22.0). We filtered data using the following exclusion criteria: history of suicide risk or any other untreated psychiatric disorder, unknown molecular study findings, and clear symptoms of HD or any other neurological disease. The final sample included 175 patients (92.5% of the 189 HDPTP participants) who completed the assessment scales and met the inclusion criteria.

The sample was categorised as in other studies,23–26 and divided in 2 groups: carriers of the HD mutation, referring to those with ≥ 36 CAG triplet repeats in the huntingtin gene, and non-carriers, referring to those with ≤ 35 CAG triplet repeats.

Once the number of CAG triplet repeats in each participant was determined, the disease burden was calculated using the Penney et al.25 formula: CAP = (age at study inclusion) × (CAG − 35.5), which is the most widely cited and used in international studies. We obtained a range from 30 to 957 (mean, 294.65 [SD: 122.22]).

We used the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to analyse normal distribution. We performed a descriptive analysis of demographic data, BDI-IA and BAI results, and total MMSE scores, and compared the findings between carriers and non-carriers. The chi-square test or Fisher exact test were used for categorical variables and the t test or Mann–Whitney U test to analyse differences between groups. We used Spearman’s ρ to examine correlations. Lastly, we conducted a multiple linear regression analysis to estimate the strength of association between disease burden and psychiatric symptoms. We calculated the regression coefficient (β), P-value, adjusted R2 value, and variance inflation factor. In all comparisons, we assumed an α value of .05.

We subsequently used the formula proposed by Brandt et al.26 to classify carriers into 3 groups: 1) the far-from-onset group, ie, those who are estimated to present cognitive symptoms and be diagnosed in more than 15 years; 2) the moderate distance group, including patients who are expected to present cognitive symptoms and be diagnosed in 9–15 years; and 3) the close-to-onset group, including those who are likely to present cognitive symptoms and be diagnosed within 9 years.

As the HDPTP participants came from urban areas, the statistical analysis used data from the general population to calculate specific T scores for SCL-90-R results. We compared SCL-90-R scores (dependent variables) using the Kruskal–Wallis test, with proximity to onset being the independent variable.

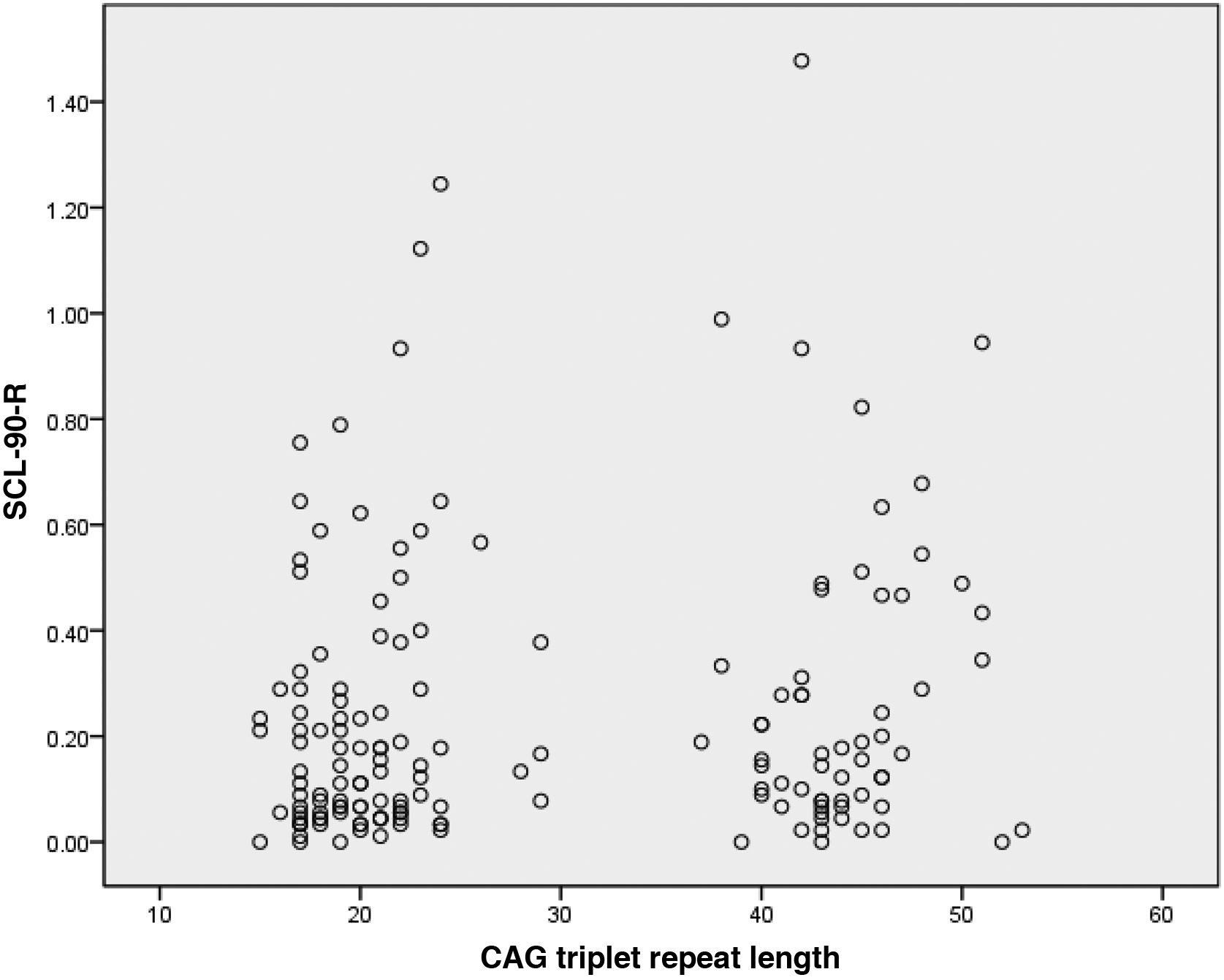

ResultsOf the 175 HDPTP participants, 69 (39.4%) were carriers of the HD mutation and 106 (61.6%) were non-carriers. The mean number of CAG triplet repeats was 44.2 (SD: 3.3; range: 37−53) in carriers and 20.5 (3.7; range: 15−29) in non-carriers (Fig. 1). We observed no statistically significant difference in age or education level between groups. The non-carrier group included a higher percentage of women.

We only included participants with no cognitive impairment, according to MMSE score, and with a Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale score of 0, and who obtained scores within the mild to moderate range in the BAI and BDI-IA. In accordance with HDPTP exclusion criteria, we excluded patients with severe depression. Of the total sample, 6.3% of participants presented mild depression, 1.2% moderate depression, 15.3% mild anxiety, and 5.1% moderate anxiety. We observed no statistically significant differences between groups in BAI and BDI-IA scores. We did observe statistically significant differences in MMSE scores (P = .001). Table 1 presents these variables broken down by group.

Demographic and mental health variables and MMSE scores of both groups.

| Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carriers | Non-carriers | |||

| (n = 69) | (n = 106) | F | P | |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 38 (55.1) | 67 (63.6) | 0.361* | .548 |

| Men | 31 (44.9) | 39 (36.4) | ||

| Age | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 35.3 (10.1) | 37.3 (11.6) | 1.229 | .221 |

| Range | 20−63 | 19−66 | ||

| Years of schooling | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.4 (2.9) | 14.0 (3.2) | 0.945 | .346 |

| Range | 7−18 | 6−18 | ||

| Depression | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.5 (4.5) | 2.1 (3.2) | 2.126 | .023 |

| Range | 0−25 | 0−25 | ||

| Anxiety | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.4 (6.0) | 3.8 (6.1) | 0.572 | .568 |

| Range | 0−30 | 0−30 | ||

| MMSE | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 27.8 (1.9) | 28.9 (1.2) | −4.566 | .001 |

| Range | 23−30 | 23−30 | ||

| CAG | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 44.2 (3.3) | 20.5 (3.7) | 2258.902 | .001 |

| Range | 37−53 | 15−29 | ||

When we compared the SCL-90-R results for carriers and non-carriers, we observed that carriers scored higher in all dimensions of psychiatric symptoms (Table 2), although we only observed statistically significant differences in the PSDI, in which carriers obtained a higher average score than non-carriers (1.32 [0.3] vs 1.24 [0.39]).

Psychological distress in carriers and non-carriers of the Huntington disease mutation, according to the SCL-90-R.

| Groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carriers n = 69 | Non-carriers n = 106 | |||||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | P |

| Somatisations | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.32 | –0.950 | .342 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.38 | –1.298 | .194 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.17 | 0.28 | –1.071 | .284 |

| Depression | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.37 | –0.863 | .388 |

| Anxiety | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.21 | –0.014 | .989 |

| Hostility | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.27 | –1.792 | .073 |

| Phobic anxiety | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.24 | –0.802 | .423 |

| Paranoid ideation | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.34 | –0.358 | .721 |

| Psychoticism | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.23 | –1.850 | .064 |

| Additional items | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.28 | –0.391 | .696 |

| GSI | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.25 | –1.116 | .264 |

| PST | 15.34 | 16.07 | 14.40 | 14.25 | –0.064 | .949 |

| PSDI | 1.32 | 0.32 | 1.24 | 0.39 | –1,966 | .049* |

GSI: Global Severity Index; PSDI: Positive Symptom Distress Index; PST: Positive Symptom Total; SD: standard deviation.

Correlation analysis showed associations between disease burden and psychological distress. These associations were observed in the following dimensions: obsessive-compulsive disorder (ρ = 0.169; P = .031), interpersonal sensitivity (ρ = 0.167; P = .034), hostility (ρ = 0.192; P = .015), GSI (ρ = 0; P = .046), and PSDI (ρ = 0.199; P = .013). In general, these associations are weak but positive.

Table 3 shows the multivariate linear regression model used to determine the relationship between disease burden and psychological distress, according to SCL-90-R results, in carriers. We weighted scores for depression, observing that hostility, phobic anxiety, and psychoticism were predictors of disease burden.

Multivariate linear regression model of the association between disease burden and symptom domain according to the SCL-90-R in carriers of the Huntington disease mutation.

| Disease burden | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| General model: | |||

| R2 = 0.26; adjusted R2 = 0.24; F = 6.46; P = .001. |

| Predictor variables | Standardised β | P | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hostility | 0.362 | .001 | 1.50 |

| Phobic anxiety | −0.563 | .001 | 1.89 |

| Psychoticism | 0.347 | .013 | 2.29 |

GSI: Global Severity Index; PSDI: Positive Symptom Distress Index; PST: Positive Symptom Total; VIF: variance inflation factor.

Fig. 2 shows the interaction between these variables and presence or absence of the Huntington disease mutation. Our final calculation revealed that this model explains 26.9% of variance.

Comparison of proximity to onset (age at symptom onset)Of the 69 carriers, 57 (82.6%) were classified according to proximity to onset. We were unable to classify 12 due to lack of data; 8 were included in the far-from-onset group, 15 in the moderate-distance group, and 34 in the close-to-onset group. The Kruskal-Wallis test showed the following results: for the obsessive-compulsive disorder dimension of the SCL-90-R, the far-from-onset group scored lower than the other groups. The same tendency was observed in the interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety, phobic anxiety, and paranoid ideation dimensions. We also observed the same tendency for the GSI and PST (Table 4).

Analysis of psychological distress domains according to proximity to onset (time to diagnosis of motor symptoms).

| Close-to-onset | Moderate-distance | Far-from-onset | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 34 | n = 15 | n = 8 | KW | P | ||||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Somatisations | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 4.967 | .083B |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 7.968 | .019*,B, C |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 6.502 | .039*,B |

| Depression | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 5.905 | .052B, C |

| Anxiety | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 10.195 | .006*,B, C |

| Hostility | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 2.256 | .324 |

| Phobic anxiety | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 6.218 | .045*,B |

| Paranoid ideation | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.282 | .002*,B, C |

| Psychoticism | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 3.342 | .188 |

| Additional items | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 2.652 | .266 |

| Global Severity Index | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 9.464 | .009*,B, C |

| Positive Symptom Total | 13.1 | 12.7 | 25.2 | 17.5 | 9.0 | 8.2 | 8.435 | .015*,B, C |

| Positive Symptom Distress Index | 1.18 | 0.42 | 1.42 | 0.31 | 1.38 | 0.39 | 5.177 | .075B |

Close-to-onset: expected diagnosis of Huntington disease within 9 years; moderate distance: expected diagnosis of Huntington disease in 9–15 years; far-from-onset = expected diagnosis of Huntington disease in more than 15 years. SD: standard deviation. *P < .05. The Mann–Whitney U test detected significant differences between close-to-onset vs far-from-onset (A); close-to-onset vs moderate-distance (B); moderate distance vs far-from-onset (C).

Several studies report that both carriers and non-carriers of the Huntington disease mutation present normal cognitive performance.27,28 However, despite both groups obtaining results within normal ranges, we observed statistically significant differences between groups in total MMSE score.19 It is widely known that psychiatric manifestations tend to affect cognitive performance in subjects at risk of developing HD; therefore, emphasis should be placed on managing these alterations from presymptomatic stages of the disease.

This is the first study in a Hispanic population to analyse psychological distress in carriers and non-carriers of the HD mutation. However, although we identified no statistically significant differences between groups in terms of anxiety and depression symptoms, we did observe higher prevalence for anxiety (mild [14.3%] and moderate [5.1%]) than for depression in our total sample. This confirmed the findings of Berrios et al.29 and Julien et al.,4 who reported anxiety rates between 11.5% and 17% in patients with presymptomatic HD, which increased in participants who were closer to motor diagnosis.30

Although depressive symptoms may develop at any time during disease progression, high levels of depression and anxiety have been reported during the period of time in which genetic tests are performed31,32 and before the clinical motor diagnosis of HD.33 Psychiatric symptoms may be considered part of the prodromal stage of HD, and may be the first markers of the disease, as clinical diagnosis is not established until the onset of motor symptoms.

Overall, we found that carriers scored higher than non-carriers in all the dimensions assessed with the SCL-90-R, although no statistically significant differences were observed, unlike in previous studies.12 The only statistically significant difference was found in the PSDI, in which carriers presented the highest score; we should mention that the scores obtained (less than 4) suggest symptom denial or minimisation.34 Higher scores in all the SCL-90-R dimensions in carriers may suggest early detection of psychiatric symptoms and may be a target for treatment of these patients. Interpersonal sensitivity, hostility,30 and apathy35 are the most frequently reported symptoms in carriers.

We observed weak but significant associations between disease burden and the psychological distress, as assessed with the SCL-90-R, in the following dimensions: obsessive-compulsive disorder, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility, GSI, and PSDI. These associations are consistent with findings from other studies.30,36 We also identified hostility, phobic anxiety, and psychoticism as predictors of disease burden.

When comparing by proximity to onset, we observed that several SCL-90-R dimensions (obsessive-compulsive disorder, interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety, phobic anxiety, and paranoid ideation) presented significant differences (P < .05), with the far-from-onset group obtaining the lowest score. These data are similar to those observed in other studies that report psychiatric symptoms manifesting before the clinical onset of the disease.7,30,36 This is consistent with the results of other studies using the SCL-90-R to assess patients with prodromal HD and showing greater severity of psychiatric symptoms associated with the estimated proximity to onset.30,36

Obsessive-compulsive disorders have been associated with HD progression and neuropsychological deficits. A significant number of patients with HD present symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder, without necessarily meeting diagnostic criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder according to the DSM-V.37 Symptoms may manifest in preclinical stages, and more significantly in advanced stages of the disease.38 Studies have reported that approximately 27% of patients in preclinical stages of HD present some obsessive-compulsive symptom and that obsessive thinking and compulsive behaviour increase in line with proximity to motor diagnosis, subsequently stabilising.39 Another study identified mild obsessive-compulsive symptoms in 13% of patients, and moderate to severe symptoms in another 13%.40

Anxiety is frequent in HD, with prevalence ranging from 13% to 71%; it increases with motor diagnosis and disease progression,30,41 which highlights the relevance of evaluating and treating patients at different stages of the disease.

Marshall et al.36 reported significantly higher scores in carriers than in non-carriers for 3 SCL-90-R dimensions (anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism). Striatal and orbitofrontal-subcortical degeneration is known to favour the onset of socially inappropriate behaviours (interpersonal sensitivity, paranoid ideation), which may be subtle at onset and increase with time. As found in our study, such behaviours are more likely to present in stages closer to diagnosis of motor symptoms of HD.

Psychiatric symptoms have a great impact on patients as they reduce autonomy, increase cognitive impairment, and affect quality of life and functional status; they also increase caregiver burden.42,43

One limitation of this study may be the different number of patients in each group (carriers and non-carriers), although the international literature reports an increased number of participants with negative results, and the progressive reduction of this difference.44 Since the HDPTP was launched, growing numbers of patients with negative results, and predominantly women, have requested enrolment in HD programmes.45 It is important to mention that the majority of the patients requesting enrolment in the HDPTP are Mexican and of mixed race, from the city and greater metropolitan area of Mexico City, partly due to the location of our centre (far from rural communities), which prevents us from including more participants.

Despite the potential implications of the criteria used to select the participants in this study, as results may not be generalised to all the individuals at risk of developing HD, our findings are consistent with those of other studies reporting that affective disorders are a significant characteristic of prodromal HD and show a strong correlation with the clinical onset of motor symptoms.4 Further longitudinal studies will be essential to characterising the onset and progression of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with HD.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, private, or non-profit organisation.

Conflicts of interestNone.