Within the causes of secondary headaches, there is a subgroup associated with disorders of homeostasis, with an underlying process of variable severity sometimes being the only manifestation. This clinical scenario is frequent among elderly patients, and may represent a diagnostic challenge. This is the case for cardiac cephalalgia; it is important to recognise this rare entity as it is also an anginal equivalent.

We present the case of a 74-year-old woman with history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidaemia, who was attended at the emergency department due to a 3-week history of headache. Pain was intermittent and triggered by mild effort, for instance while walking on flat ground (she was previously able to do this without exertion), and remitted with rest. Headache started in the vertex and radiated bilaterally to the frontal and lateral cervical areas. Pain was oppressive, of moderate intensity, and responded poorly to oral analgesia with paracetamol. The patient did not present hypersensitivity to sound or light and was not awakened by pain; pain was not exacerbated with Valsalva manoeuvres. The patient presented no other associated neurological or systemic symptoms, including chest pain. She visited the emergency department on 3 occasions, and headache improved with rest and intravenous analgesia (metamizole, dexketoprofen, or paracetamol). No preventive treatment was indicated. The day before her last visit, headache progressed and manifested even during rest; the pain increased in intensity and was accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

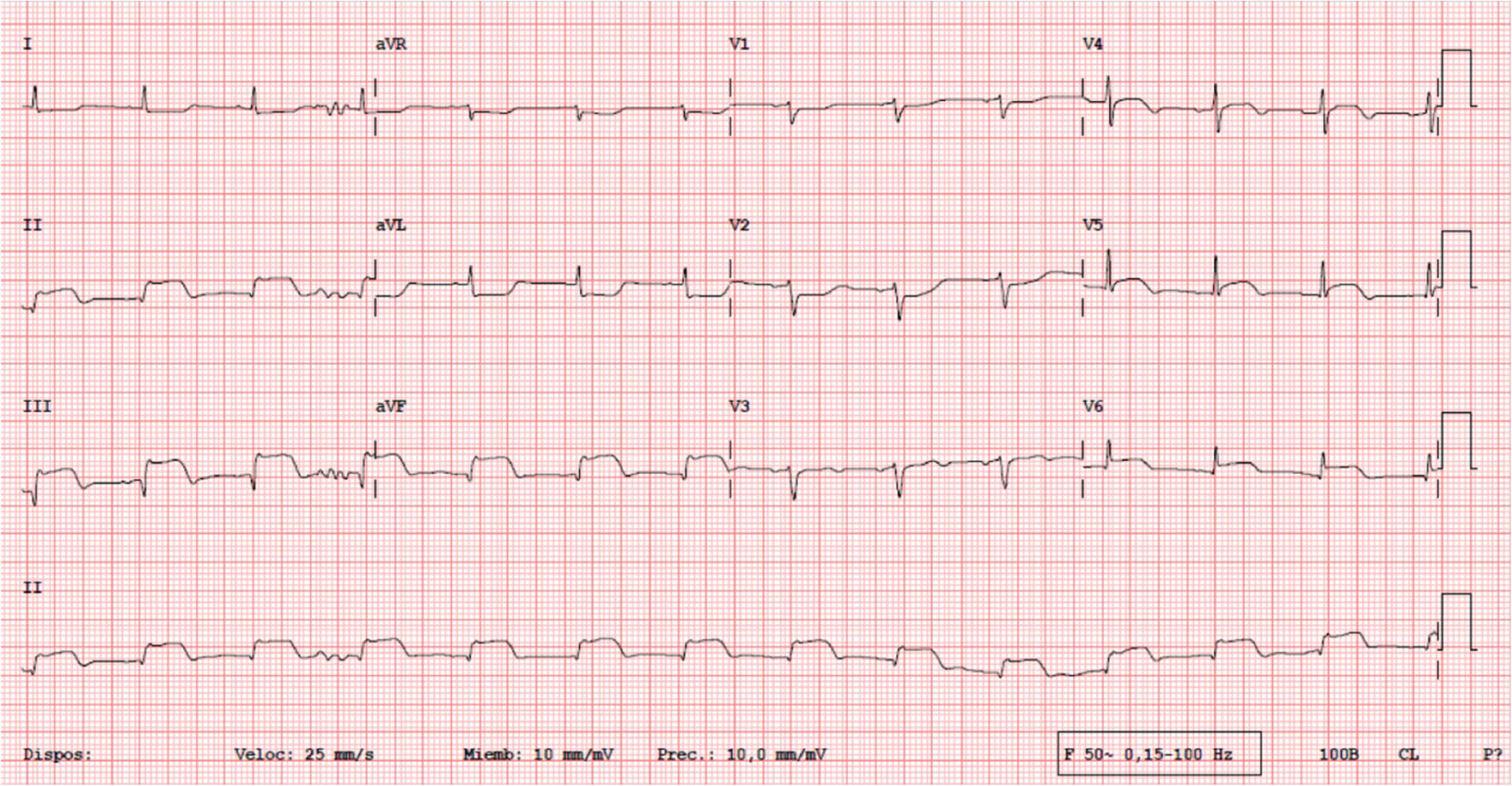

Results from the neurological and physical examination were normal. Laboratory analysis showed leukocytosis (16870cells/mm3) with a predominance of neutrophils, C-reactive protein at 5.17mg/mL, aspartate transaminase at 723IU/L, alanine aminotransferase at 623IU/L, LDH levels of 702IU/L, and prolonged activated partial thromboplasmin time (84seconds). A CT scan revealed no abnormalities. Given the suspicion of headache associated with systemic diseases, we requested an ECG, which showed ST segment elevation in the inferior and lateral side (Fig. 1), and a cardiac profile test, which detected troponin T levels of 2626 ng/L (normal level: <14 ng/L). Immediately after, the patient became haemodynamically unstable and was transferred to the coronary care unit with a diagnosis of acute inferior-posterior-lateral myocardial infarction (Killip class IV), ischaemic hepatitis, and associated mild bleeding disorder. An emergency coronarography revealed 3-vessel disease with occlusion of the right coronary artery. All lesions were revascularised with pharmacoactive stents, and individualised treatment was started with dual antiplatelet therapy (acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel) and anticoagulation with acenocoumarol (due to presence of an apical thrombus in the right ventricle). At discharge the patient presented a left ventricle ejection fraction of 30% and a New York Heart Association functional classification of II, and was able to make moderate efforts with no headache relapse at 6 months of follow-up.

The term cardiac cephalalgia was first coined by Lipton et al.1 in reference to cases of headache triggered by physical exercise in the context of myocardial ischaemia. According to the third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders, cardiac cephalalgia is a migraine-like headache, usually but not always aggravated by exercise, occurring during an episode of myocardial ischaemia. It is relieved by nitroglycerine. Diagnosis is supported by pain of moderate or severe intensity and in association with nausea but not sensitivity to sound or light. No more probable alternative cause should exist.2

Cardiac cephalalgia is a very infrequent entity. Bini et al.3 reviewed and analysed the clinical characteristics of the 30 clinical cases published in English-language articles. Mean age was 62.4 years (range, 35-85); by sex, 63.3% of patients were men and 36.7% were women. Pain location and characteristics were varied, resembling a migraine or tension-type headache associated with physical exercise or stress, but also manifesting during rest. Most patients also presented typical chest pain or another anginal equivalent; however, headache was the only symptom in 27% of cases (particularly in elderly patients).3 As in our case, it is likely that diabetic dysautonomia would contribute to concealing chest pain. More than half of the patients presented ECG alterations or elevated levels of cardiac enzymes.3 In some patients, in line with clinical suspicion, the study was complemented with a cardiac stress test and a coronarography. In all cases, headache resolves with revascularisation or satisfactory conservative treatment.4

The pathophysiology of the condition remains unclear. Several theories have been suggested: 1) cardiac cephalalgia is a type of referred pain; 2) pain is caused by a mechanism of intracranial hypertension due to venous stasis secondary to a transient decrease of cardiac output; or 3) the heart muscle locally releases chemical mediators capable of inducing remote pain (adenosine, bradykinin, histamine, or serotonin), which would act intracranially.3–5 A recent study demonstrated cortical hypoperfusion during a headache attack, suggesting the possibility of a mechanism similar to that occurring due to catecholamine release in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome.6 Although cardiac cephalalgia is rare, it is important to include it in the differential diagnosis of new-onset headache in patients older than 50 years presenting vascular risk factors, especially when pain is associated with effort; early diagnosis can have significant consequences and implications for treatment and prognosis.3,5,6

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz Ortiz M, Bermejo Guerrero L, Martínez Porqueras R, González de la Aleja J. Cefalea cardíaca: cuando la isquemia miocárdica llega a la consulta del neurólogo. Neurología. 2020;35:614–615.