Background/Objective: Despite the great interest that bullying and cyberbullying have received during the last decades, the problem of defining these phenomena is still debated. Recently, this discussion has also been articulated in terms of how young people who are directly involved in bullying and cyberbullying understand these notions. This study aimed at investigating the operational definitions of both bullying and cyberbullying provided by adolescent victims and perpetrators, by inquiring the weight of traditional criteria (i.e., frequency, deliberateness, imbalance of power, and harm) as well as dominance in the perception of these phenomena. Method: A total of 899 students aged between 11 and 16 years filled out the Student Aggression and Victimisation Questionnaire. Results: Common traits and differences between the operational definition of bullying and cyberbullying and between the perspectives of victims and perpetrators of aggression were found. The most relevant criterion for the perception of both these phenomena was clearly the presence of dominance. By contrast, the imbalance of power showed no significant relationship with the perception of being bullied or bullying others both offline and online. Conclusions: Findings emphasise that young people conceptualise bullying with a clear reference to relational and group processes, rather than to individual differences.

Antecedentes/Objetivo: A pesar del gran interés que el bullying y el cyberbullying han despertado durante las últimas décadas, el problema de la definición de estos fenómenos es todavía motivo de debate. Recientemente, la literatura ha abarcado esta controversia a partir de la comprensión que los jóvenes tienen del bullying y cyberbullying. Este artículo investiga las definiciones operativas, proporcionadas por víctimas y agresores, tras analizar la envergadura que tienen estos factores: frecuencia, intencionalidad, desequilibrio de poder, daño y dominancia. Método: Un total de 899 alumnos entre 11 y 16 años rellenaron el Student Aggression and Victimisation Questionnaire. Resultados: Los resultados evidenciaron rasgos comunes y diferencias entre las definiciones operativas de bullying y cyberbullying, al igual que entre las perspectivas de víctimas y perpetradores. El criterio más relevante para la definición de ambos fenómenos fue la percepción de la dominancia. En cambio, el desequilibrio de poder no mostró relaciones significativas con la definición de bullying y cyberbullying. Conclusiones: Estos hallazgos hacen hincapié en cómo los jóvenes interpretan el bullying, con un enfoque en los procesos relacionales y grupales, más que en las diferencias individuales.

The first studies on bullying date back to the 1970s (Olweus, 1974), but the theme was popularised mainly from the 1990s, thanks to the continued efforts of Dan Olweus, who defined it as comprising the following criteria: “(a) It is aggressive behavior or intentional "harmdoing" (b) which is carried out "repeatedly and over time" (c) in an interpersonal relationship characterized by an imbalance of power” (Olweus, 1994, p. 1173). During the last few decades, bullying has established itself as a key topic in developmental and educational psychology. This great interest is partially explained by the wide diffusion of this phenomenon, with prevalence rates estimated around 20% in adolescents for both perpetration and victimisation (Smith, 2016). Nevertheless, estimates across studies show high variability, with e.g. face to face bullying perpetration rates ranging from 10% to 90% (Modecki et al., 2014; Zych et al., 2017). At the turn of the 21st century, the diffusion of a new form of peer aggression taking place online via electronic devices, labelled “cyberbullying”, has further revived the interest around this issue (Olweus & Limber, 2018; Slonje & Smith, 2008).

An increasing volume of studies shows that victimisation, both offline and online, can cause serious emotional consequences, even increasing the risk for long-term depression (Moore et al., 2017) and suicidal ideation (Lucas-Molina et al., 2018). However, despite the ever-increasing volume of publications focusing on different types and aspects of bullying phenomena, the problem of defining bullying is still a subject for a complex and multifaceted debate (Younan, 2019).

A first aspect of this discussion revolves around the inclusion of different types of aggression. The notion of bullying, originally limited to physical and verbal harassment, was broadened already in the 1990s to encompass also indirect and relational bullying (Björkqvist et al., 1992). During the last two decades, the original conceptualisation of bullying has also been challenged by its application to contexts different from the school environment where it was originally formulated. The study of bullying among prisoners, for example, led to the notion that repetition might not be a valid criterion for identifying bullying instances in all settings (Ireland, 2000). The rapid and continual movement of inmates, in fact, makes repeated aggression less likely, but even single attacks can cause serious emotional and behavioural consequences.

The traditional criteria used to define bullying are particularly problematic when applied to cyberbullying, as an act such as creating a defamatory post online can have a long-lasting effect due to its continuous visibility, regardless of the lack of repetition (Slonje & Smith, 2008). The way imbalance of power manifests in cyberbullying is also peculiar, being related to technological competences and anonymity (Ansary, 2020; Menesini et al., 2013). As reported by a recent review of cyberbullying by Peter and Petermann (2018), 24 different definitions of cyberbullying were proposed between 2012 and 2017. With regard to bullying, Vivolo-Kantor et al. (2014), in an overview of measures that identified specific components of bullying across studies published between 1988 and 2008, pointed out that less than half captured all five components (i.e., power imbalance, intention to harm, victim experiences harm, repetition, and aggressive behaviour). The components most often included in the definition were power imbalance, intention to cause harm and aggressive behaviour (Vivolo-Kantor et al. 2014).

Besides the debate about the types of phenomena to be included under this concept (Slonje & Smith, 2008) and the theoretical rethinking of the criteria that should be used to define bullying (Volk et al., 2014), the discussion about what constitutes bullying has also been articulated in terms of how different groups of people involved in bullying (e.g., bully, assistant of the bully, defender of the victim, and outsider) view this phenomenon and what types of events they recognise as bullying (Eriksen, 2018). Several studies over the last two decades have inquired about the definitions of bullying and/or cyberbullying adopted by victims (Alipan et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2011; Dredge et al., 2014; Mishna, 2004), perpetrators and bystanders (Alipan et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2011), mainly by asking adolescents, either in written or oral form, to provide a definition of the phenomena.

Although from a theoretical standpoint repetition is considered a key criterion to identify face to face bullying incidents, several studies investigating children and adolescents’ definitions of bullying have found that young people do not consistently include this construct (Cheng et al., 2011; Mishna, 2004; Vaillancourt et al., 2008). Generally, studies have found that young people do not consider the criterion of repetition important for bullying (Cuadrado-Gordillo, 2012). On the other hand, although cyberbullying is generally considered by scholars to be identifiable even with single instance offences, different studies have found repetition to be one of the criteria of young people’s definitions of cyberbullying (Höher et al., 2014; Nocentini et al., 2010; Vandebosch & Van Cleemput, 2008).

A similar trend is detectable in literature for the criterion of intentionality, which was not found to be consistently mentioned by students in defining bullying (Cheng et al., 2011; Frisén et al., 2008; Mishna, 2004; Vaillancourt et al., 2008), with as few as 1.70% of students referring to it when asked to describe bullying. On the other hand, some studies found that the perceived deliberateness of online aggressions plays a role in adolescents’ definitions of cyberbullying (Höher et al., 2014; Nocentini et al., 2010; Vandebosch & Van Cleemput, 2008). Power imbalance, consistently with academic definitions, was generally mentioned as a criterion for defining face to face bullying (Cheng et al., 2011; Frisén et al., 2008; Mishna, 2004; Vaillancourt et al., 2008), while it was rarely indicated as important in cyberbullying definitions (Ansary, 2020; Dredge et al., 2014; Höher et al., 2014; Nocentini et al., 2010). A focus group study by Vandebosch and Van Cleemput (2008) concluded that disparities in young people’s information and communication technologies-related competences would make cyberbullying possible, irrespective of any real-life power imbalance between cyberbullies and victims. Other studies have suggested that cyberspace inherently contributes to the power imbalance (for a review see Ansary, 2020). Indeed, online users through the disinhibition effect (Suler, 2004) can be more brazenly and can attack anonymously.

Physical or emotional consequences of aggression have often been reported as the most common aspect characterising traditional bullying (Cheng et al., 2011; Frisén et al., 2008; Mishna, 2004; Vaillancourt et al., 2008) as well as cyberbullying (Dredge et al., 2014; Höher et al., 2014; Nocentini et al., 2010; Vandebosch & Van Cleemput, 2008). Bullying and cyberbullying are generally considered to be the most harmful form of peer aggression. However, recent data show that even non-bullying aggression can be perceived as very harmful by victims (Skrzypiec et al., 2019).

Most recently, the literature has been shifting towards an increasingly systemic interpretation of bullying (Duffy & Nesdale, 2009; Duffy et al., 2016; Farrell & Dane, 2019; Olthof et al., 2011; Rey et al., 2020) and the notion of dominance, originally introduced in the study of bullying by Björkqvist et al. (1992) has been revived in the debate about the definition of bullying (Farrell & Dane, 2019; Goodboy et al., 2016; Olthof et al., 2011; Pellegrini, 2001). In particular, several scholars suggest that bullying should not be considered simply in terms of a deviant behaviour, but should, to some extent, be interpreted as an adaptive strategy employed to negotiate social hierarchies (Goodboy et al., 2016; Ireland, 2000), establish membership within a desired group (Volk et al., 2014) and even initiate heterosexual relationships (Pellegrini, 2001). More specifically, according to the Social Dominance theory (Sidanius & Pratto, 2004) and the dominance theory (Goodboy et al., 2016), youth bully one another in attempts to gain group and individual levels of social dominance, and subsequently to maintain their social status. Some research has confirmed the role of social dominance goals also in cyberbullying (McInroy & Mishna, 2017; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004).

So, to sum up, different behaviours generally considered as bullying and cyberbullying in literature may not be perceived as such by adolescents and young people involved in these episodes (Cuadrado-Gordillo, 2012; Ireland, 2000; Vaillancourt et al., 2008). Most of the existing studies investigating adolescents’ conceptualisations of these phenomena have employed qualitative methodologies, including open-ended survey questions (Cheng et al., 2011; Frisén et al., 2008; Vaillancourt et al., 2008), focus groups with abstract scenarios (Höher et al., 2014; Vandebosch & Van Cleemput, 2008) and interviews (Dredge et al., 2014; Guerin & Hennessy, 2002; Mishna, 2004; Nocentini et al., 2010).

Therefore, investigating adolescents’ direct perceptions of what is and what is not bullying or cyberbullying may help researchers to construct a shared meaning of them and to better understand their psychological consequences. The way in which people cope with a stressful situation, such as bullying or cyberbullying, in fact, does not depend exclusively on the event itself but also on how people assess it (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to undertake an investigation of how perpetrators and victims of aggression assess bullying in terms of dominance, as well as all its defining criteria. Results could be relevant for the theoretical discussion about the perceptions and definitions of bullying and cyberbullying, as well as in helping to design more pertinent policies, intervention and prevention programmes.

The aim of this study was to investigate the operational definitions of bullying and cyberbullying through the perceptions of adolescent victims and perpetrators of aggression. To overcome the abstract character of studies based on general questions, we investigated actual cases of aggression perpetrated or experienced by students. The traditional criteria for defining bullying and cyberbullying (i.e., frequency, deliberateness, imbalance of power and harm) as well as the revived notion of dominance, were considered in order to assess how much weight these elements would hold in operational definitions of these phenomena by adolescent aggressors and victims, controlling for gender and school order.

Based on dominance theory, we expected that, especially for the perception of bullying victimisation, relational aspects (i.e., intention to harm and dominance) would be crucial in conceptualising bullying and cyberbullying, and that social dominance in particular would be strictly connected with both perpetrators’ and victims’ perceptions of bullying and cyberbullying.

MethodParticipantsA convenience sample of 899 adolescents was recruited on a voluntary basis among schools located in Central and Northern Italy in the Emilia-Romagna, Toscana and Veneto regions. The sample included 494 middle school (grades 6-8) and 405 high school (grades 9-10) students, from 4 public middle schools and 2 public technical secondary schools. Data were collected in 2017 in the context of an international study on peer aggression (Skrzypiec et al., 2018). Because technical schools, at least in Italy, are generally attended by a majority of male students, only 32% (n = 286) of respondents were females, while the remaining 68% (n = 608) were males. The age of respondents ranged between 11 and 16 years (M = 13.33, SD = 1.56).

InstrumentsThe Student Aggression and Victimisation Questionnaire (SAVQ; Skrzypiec et al., 2018) was translated into Italian and back-translated (Guarini et al., 2019). The SAVQ questionnaire consists of 20 main items, including 11 victimisation experiences (e.g., “I had things taken from me”, “I was threatened”) and 9 experiences of aggression (e.g., “I hit, kicked or pushed someone around”, “I left someone out”). For each of these items, participants who had answered positively were asked seven additional questions, including where the incidents happened (i.e., “At school”, “On the way to/from school”, “At home”, “Online” and “Elsewhere”). Answers were coded binomially in order to distinguish between cyberbullying (when the answer was “Online”) and face to face bullying. Other subsequent items sought to evaluate the perceived harm caused by the aggression (“How harmful was it to you?” for victimisation main items and “How harmful was it to them?” for aggression main items), deliberateness (“Did the person(s) deliberately intend to do this to you?” for victimisation, and “Did you deliberately intend to do this?” for aggression), frequency (“During the last three months, how often [did this happen]?”), dominance (“How strongly do you feel that this person/s dominates (controls or overpowers) you?”), and imbalance of power (“How powerful -important, liked, strong- are you compared to this person/s?”). Another item asked how much respondents considered these acts as instances of bullying (“How strongly do you feel that this person/s bullied you by doing this” for victimisation, and “How strongly do you feel that in doing this you bullied the person/s concerned” for aggression). Answers for these questions were on Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (e.g., Not harmful at all, Not intentional at all) to 5 (e.g., Extremely harmful, Absolutely intentional), except for the frequency item, which was answered on an 8-level scale, ranging from 1 (Never) to 8 (More than 3 times a week). Both the victimisation (GLB = .78, ω = .75) and the aggression scale (GLB = .72, ω = .72) showed acceptable reliability.

ProcedureThe questionnaire was filled in online by students during school hours through Qualtrics platform. Teachers provided for each student a link to fill in the questionnaire in the information technology (IT) classroom. Teachers remained in the IT classroom while the questionnaires were being filled in, so as to clarify any questions or problems.

The study protocol met the ethical guidelines for the protection of human participants, including adherence to the legal requirements of Italy, and received a formal approval by the local Bioethics Committee, University of Bologna. Parents gave their informed written consent for the participation of their son/daughter in the study. Teachers explained that the questionnaire was voluntary, anonymous, and that participants could withdraw and not answer any questions they did not wish to, prior to students providing their consent.

Data analysesTo analyse the factors concurring with the operative definitions of bullying adopted by victims and perpetrators, both in online and offline settings, the dataset was formatted making instances of victimisation/perpetration the statistical unit (N= 2,946). Four separate datasets were obtained, for offline aggression, offline victimisation, online aggression and online victimisation. In order to account for the hierarchical structure of the dataset (with victimisation/perpetration experiences nested in participants) multilevel regressions with participant ID as random intercept were fitted, with the item asking “How strongly do you feel that this/these person/s bullied you by doing this?” as the outcome. Two separate models, with gender, school level (middle-school, high school), frequency, deliberateness, power imbalance, perceived harm, and dominance as predictors, were regressed on bullying victimisation (Model 1) and bullying perpetration (Model 2) items as separate subsamples. Two additional models were fitted for cyberbullying victimisation (Model 3) and for cyberbullying perpetration (Model 4) items. All analyses were carried out using the lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al., 2017) package in the R statistical environment, version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2020).

ResultsDescriptive statisticsOut of 894 participants, 460 (51.50%) reported to have undergone at least one instance of bullying victimisation during the last three months, and 331 (37%) admitted to at least one instance of bullying perpetration. Moreover, 186 respondents (20.80%) reported cyberbullying victimisation during the same period and 70 (7.80%) declared to have perpetrated at least one cyberbullying aggression. In total, 1,670 instances of bullying victimisation, and 835 instances of bullying perpetration were included in the analyses, together with 336 instances of cyberbullying victimisation and 105 of cyberbullying perpetration.

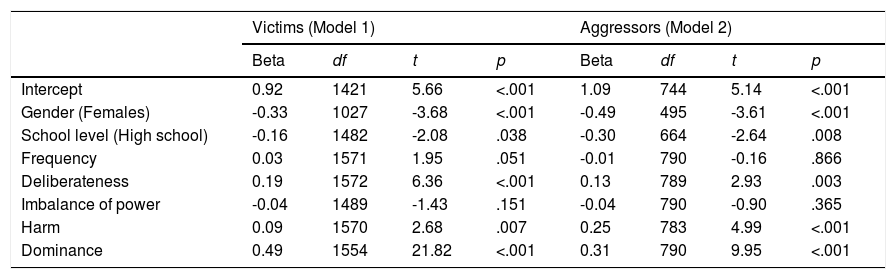

Perception of bullyingAs highlighted in Table 1, multilevel regressions showed that the most important factor in the model predicting the perception of bullying was dominance, both for victims, β = 0.49, t(1554) = 21.82, p < .001, and perpetrators, β = 0.31, t(790) = 9.95, p < .001. The deliberateness of the aggression also positively predicted the perception of being bullied, β = 0.19, t(1572) = 6.36, p < .001, and of acting as a bully towards others, β = 0.13, t(789) = 2.93, p = .003. The perceived harm, on the other hand, was a stronger predictor for perpetrators. Furthermore, the reported frequency showed a non-significant effect on the perception of being bullied, β = 0.03, t(1571) = 1.95, p = .051, and no effect at all on the perception of acting as a bully, β = -0.01, t(790) = -0.16, p = .86. Power imbalance was not a significant predictor of the perception of either acting as a bully or being bullied. Gender and school level highlighted significant effects on the perception of instances of aggression as bullying, both for perpetrators and victims, with girls being less likely to consider themselves as bullies, β = -0.33, t(1027) = -3.68, p < .001, and as victims of bullying, β = -0.49, t(495) = -3.61, p < .001, and middle schoolers being more inclined to label themselves as victims, β = 0.16, t(1482) = 2.08, p = .038, and actors of bullying, β = 0.30, t(664) = 2.64, p = .008, than students in high school. The intercepts were greater than zero for both victims, β = 0.92, t(1421) = 5.66, p < .001, and perpetrators, β = 1.09, t(744) = 5.14, p < .001.

Predictors of the perception of face-to-face bullying by victims and aggressors.

| Victims (Model 1) | Aggressors (Model 2) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | df | t | p | Beta | df | t | p | |

| Intercept | 0.92 | 1421 | 5.66 | <.001 | 1.09 | 744 | 5.14 | <.001 |

| Gender (Females) | -0.33 | 1027 | -3.68 | <.001 | -0.49 | 495 | -3.61 | <.001 |

| School level (High school) | -0.16 | 1482 | -2.08 | .038 | -0.30 | 664 | -2.64 | .008 |

| Frequency | 0.03 | 1571 | 1.95 | .051 | -0.01 | 790 | -0.16 | .866 |

| Deliberateness | 0.19 | 1572 | 6.36 | <.001 | 0.13 | 789 | 2.93 | .003 |

| Imbalance of power | -0.04 | 1489 | -1.43 | .151 | -0.04 | 790 | -0.90 | .365 |

| Harm | 0.09 | 1570 | 2.68 | .007 | 0.25 | 783 | 4.99 | <.001 |

| Dominance | 0.49 | 1554 | 21.82 | <.001 | 0.31 | 790 | 9.95 | <.001 |

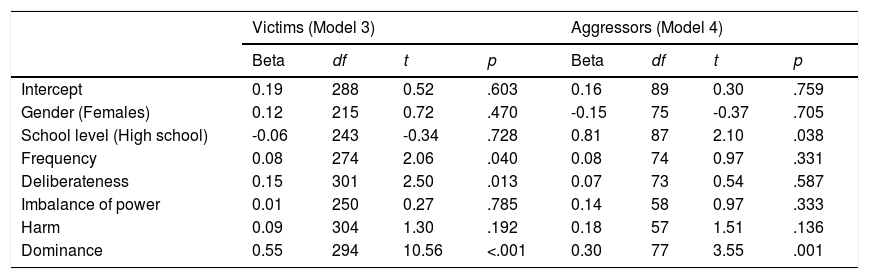

Similarly to bullying aggression, as shown in Table 2, dominance was the variable most strongly associated with the perception of being the target of cyberbullying, β = 0.55, t(294) = 10.56, p < .001, as well as of acting as a cyberbully, β = 0.30, t(77) = 3.55, p = .001. The perception of being cyberbullied was also found to be increased by the deliberateness, β = 0.15, t(301) = 2.50, p = .013, and frequency of online aggressions undergone, β = 0.08, t(274) = 2.06, p = .040. However, neither frequency nor deliberateness of online aggressions were found to be associated with the perception of acting as cyberbullies by perpetrators. Furthermore, power imbalance and harm did not show any predictive power for the perception of cyberbullying or being cyberbullied. No gender differences were highlighted, while an association with school level was found. Indeed, high schoolers were more inclined to perceive that they cyberbullied others, β = 0.81, t(87) = 2.10, p = .038. The intercepts were not significantly different from zero for both victims, β = 0.19, t(288) = 0.52, p = .603, and perpetrators, β = 0.16, t(89) = 0.30, p = .759.

Predictors of the perception of cyberbullying by victims and aggressors.

| Victims (Model 3) | Aggressors (Model 4) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | df | t | p | Beta | df | t | p | |

| Intercept | 0.19 | 288 | 0.52 | .603 | 0.16 | 89 | 0.30 | .759 |

| Gender (Females) | 0.12 | 215 | 0.72 | .470 | -0.15 | 75 | -0.37 | .705 |

| School level (High school) | -0.06 | 243 | -0.34 | .728 | 0.81 | 87 | 2.10 | .038 |

| Frequency | 0.08 | 274 | 2.06 | .040 | 0.08 | 74 | 0.97 | .331 |

| Deliberateness | 0.15 | 301 | 2.50 | .013 | 0.07 | 73 | 0.54 | .587 |

| Imbalance of power | 0.01 | 250 | 0.27 | .785 | 0.14 | 58 | 0.97 | .333 |

| Harm | 0.09 | 304 | 1.30 | .192 | 0.18 | 57 | 1.51 | .136 |

| Dominance | 0.55 | 294 | 10.56 | <.001 | 0.30 | 77 | 3.55 | .001 |

Our results highlighted elements of continuity and discontinuity between conceptualisations of bullying and cyberbullying and victims’ and perpetrators’ perceptions, suggesting that students involved in these phenomena by playing specific roles may attribute different weights to the criteria adopted for defining bullying and cyberbullying.

The most important criterion for the operational definition of bullying was the concept of dominance, both for victims and perpetrators of face to face as well as of online aggression. As detailed in the introduction, literature on traditional bullying has proposed some theoretical models for its explanation which suggest that bullying may be perpetrated in order to gain dominance in the peer group. The fact that, in our study, bullying appears so embedded in dominance dynamics, while imbalance of power shows no significant relationships with the perception of being bullied or bullying others both offline and online, is particularly innovative. Indeed, taking a step forward with respect to theoretical models and speculations, what this study suggests is that young people themselves interpret bullying with a clear reference to relational and group processes, rather than to individual differences (Salmivalli, 2010). In other words, our results seem to indicate that the imbalance between a powerful and a vulnerable individual is not perceived as relevant in personological terms, but acquires importance in its social aspects – i.e. dominance – which contributes in defining the asymmetrical nature of the relationship. Moreover, the perception of traditional bullying was positively associated with the reported harm caused by the aggression, as well as with its deliberateness, both for perpetrators and victims of aggression. However, aggressors tended to consider bullying more in terms of its exterior aspects (how much harm was done), while victims emphasised the relational aspects of dominance and intent to harm. On the contrary, with regard to the perception of cyberbullying, harm was not found to be relevant by victims nor perpetrators of aggression, while deliberateness was perceived as important in the perception of cyberbullying victimisation only.

Indeed, the lack of relevance attributed to deliberateness for the perception of cyberbullying perpetration may rely on normative and theory of mind skills, which have been reported to be lacking among young aggressors (e.g., van Dijk et al., 2017). These difficulties can be augmented in the online context, where anonymity may elicit a lack of moral emotions and moral values (Perren & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2012) compared to the context of traditional bullying.

Surprisingly, the frequency of aggressions provides quite a counterintuitive indication, as it was not a significant predictor for the perception of face to face bullying both for perpetrators and victims. These results seem to contradict the assumption that repetition plays a stronger role in offline bullying (Slonje & Smith, 2008), although they align with other studies that did not find repetition to be a decisive factor in adolescents’ definitions of bullying (Cheng et al., 2011; Mishna, 2004; Vaillancourt et al., 2008). By contrast, findings showed that repetition of the aggressive act influenced the perception of cyberbullying victimisation, in line with what has been reported by other studies (Höher et al., 2014; Nocentini et al., 2010; Vandebosch & Van Cleemput, 2008). Indeed, according to Menesini et al. (2013) repetition allows adolescents to distinguish cyberbullying victimisation from a joke. Furthermore, repetition also highlights the distinction between cyberbullying and cyberaggression, which, by definition, has a more occasional nature (Corcoran et al., 2015).

Gender differences highlighted for bullying, with girls being less likely to categorise aggression in terms of bullying, both on the perpetrator’s and the victim’s side, might be interpreted as an effect of a cultural stereotype, according to which bullying serves to reinforce hegemonic masculinity (Rosen & Nofziger, 2018). The fact that this difference was found even after controlling for repetition, deliberateness, imbalance of power, harm and dominance, indicates that the same types of incidents were perceived less often as bullying by girls. This result could partially explain gender differences typically reported for bullying perpetration and victimisation, suggesting that the lower prevalence of bullying in female adolescents might at least be partially due to under-reporting.

This study has limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting its results. Only 32% of the participants were females, and this casts a doubt on the generalisability of our findings, and beckons confirmation studies. The size of the sample did not allow further group analyses, such as investigating potential differences in operational definitions of bullying by different demographic groups (e.g., by age, gender or cultural background) or to distinguish between different types of aggression (e.g., direct vs indirect) or the bully-victim relationship (e.g., best friends, siblings or strangers). Furthermore, our analysis was focused on the perception of bullying of young people who had experienced victimisation and perpetration of peer aggression, and did not take into consideration the perceptions of other participant roles (e.g., bystanders). Finally, the use of students’ self-report data implies that our findings are based on subjective perceptions on predetermined questions. The adoption of mixed-method procedures able to combine quantitative (e.g., questionnaires) and qualitative (e.g., interview or focus groups) instruments would be useful in the future to test the reliability of our findings.

Despite these limitations, the findings discussed in this paper are promising. On theoretical and methodological levels, the strong associations highlighted in our results, and their alignment with expectations based on existing literature, suggest that the reported analyses were effective in capturing some general aspects of the operational definitions of bullying and cyberbullying in terms of the perceptions of young people involved in peer aggression. The fact that the analyses were based on the recall of actual aggression instances, perpetrated or experienced by respondents, is another strength of the present study, and ensures that our results do not pertain to an abstract idea of bullying and cyberbullying, but capture adolescents’ concrete and situated understanding of these phenomena in their daily lives.

ConclusionsTo the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to quantitatively investigate the perception of bullying and cyberbullying in young perpetrators and victims of aggression, by considering and comparing simultaneously the weight of different characteristics of aggressive acts: dominance, deliberateness, perceived harm, frequency and power imbalance. Results provide both theoretical and practical implications, highlighting that dominance was the main feature of an act of aggression in order for it to be perceived as bullying victimisation or perpetration, both in the offline and online contexts. This emphasises the systemic nature of bullying and its role in defining hierarchies and relationships within and between groups of peers. In line with previous literature, deliberateness and perceived harm also played an important role in the perception of bullying by both perpetrators and victims.

This study also has some implications for educational and clinical practices, in particular regarding the importance of focusing on group dynamics and dominance in order to prevent and contrast bullying, fostering positive relationships and productive coping strategies. Moreover, because different subpopulations of adolescents were shown to be less likely to perceive episodes of bullying perpetration and victimisation, specific strategies should be devised to target those groups (e.g., females and high schoolers).

FundingThis work was supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.