Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has a physical, psychological and social impact, often compromising the patient's ability to perform daily activities. Recently a new measurement for disability in IBD was developed. The Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Disability Score (IBD-DS) comprises the following domains: mobility, self-care, major daily life activities, gastrointestinal-related problems, mental health and interaction with the environment. The aim of our study was to translate to Portuguese and to validate the IBD-DS.

MethodsEighty-five patients, 55 with Crohn's disease (CD) and 30 with ulcerative colitis (UC), completed the Portuguese version of the IBD-DS and the short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (SIBDQ-10 questions). Disease activity was assessed using the Harvey–Bradshaw (HB) for CD and partial Mayo score (pMayo) for UC. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation between the IBD-DS and SIBDQ. The Student's t-test was used to compare the mean of IBD-DS between active and inactive disease. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 21.0 and the statistical level of significance (α) was established at 5%.

ResultsIn our study, a significant negative correlation between the IBD-DS and the SIBDQ was observed (r=−0.858, p<0.001 for CD and r=−0.933, p<0.001 for UC). There was a statistically significant difference of the mean of IBD-DS between inactive vs. active disease (93.78 vs. 117.57, p=0.016 for CD and 78.96 vs. 137.14, p<0.001 for UC).

ConclusionThe Portuguese version of the inflammatory bowel disease-disability score has a strong correlation with patients’ quality of life and clinical disease activity and was shown to be a valid tool to measure disability in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

O impacto físico, psicológico e social da doença inflamatória intestinal (DII) compromete frequentemente a capacidade do doente realizar as suas atividades de vida diária. Foi desenvolvido recentemente um novo questionário de avaliação de incapacidade na DII. O “Inflammatory Bowel Disease – Disability Score” (IBD-DS) contempla a avaliação de diferentes domínios de incapacidade na DII: mobilidade, autocuidado, principais atividades de vida diária, saúde mental, problemas gastrointestinais e impacto social. O objetivo deste estudo foi a tradução do IBD-DS para a língua portuguesa e a validação das suas propriedades de avaliação de incapacidade em doentes portugueses com DII.

Material e MétodosUm total de 85 doentes, 55 com doença de Crohn (DC) e 30 com colite ulcerosa (CU), preencheram a versão portuguesa do IBD-DS e um questionário de qualidade de vida na DII (SIBDQ-10 questões). A actividade da doença foi avaliada usando o índice de Harvey–Bradshaw (HB) para a DC, e o score parcial de Mayo (pMayo) para a CU. A correlação entre o IBD-DS e o SIBDQ foi determinada através do coeficiente de correlação de Pearson. O teste t para amostras independentes foi utilizado para comparar a média do IBD-DS entre os doentes com doença ativa e inativa. A análise estatística foi realizada com o SPSS 21.0, o nível de significância (α) foi estabelecido em 5%.

ResultadosNo nosso estudo verificou-se uma forte correlação negativa entre o IBD-DS e o SIBDQ (r=−0.858, p<0,001 para a DC e r=−0.933, p<0,001 para a CU). Foi observada uma diferença estatisticamente significativa do valor médio do IBD-DS entre doentes com doença inativa vs. ativa (93.78 vs. 117.57, p=0,016 para a DC e 78.96 vs. 137.14, p<0,001 para a CU).

ConclusãoA versão portuguesa do IBD-DS apresentou uma boa correlação com a qualidade de vida e atividade da DII, apresentando-se, deste modo, como uma ferramenta válida na avaliação de incapacidade na DII.

The inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) comprises Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), which are chronic diseases with a complex multifactorial etiology and a relapsing-remitting disease course. Clinically, they can present with a diverse set of intestinal, extra-intestinal and systemic symptoms. The chronic nature often requires repeated hospitalizations and lifelong treatments, which compromise all domains of patient's life (physical, social and psychological).

A more holistic approach to chronic diseases, namely IBD, requires particular consideration for the quality of life and disability related to disease. The World Health Organization defines quality of life as “an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”.1 In contrast, disability is the human experience of impaired body functions and structures, activity limitations, and participation restrictions in the interaction with environmental factors.2 Thus, the disability evaluation is an objective determination and differs from subjective assessments such as quality of life.

Until now, attention has been focused on the impact of IBD on patient's quality of life.3–5 On the other hand, disability in IBD remains poorly studied, since only work-related disability in IBD was reported in the literature.6–8

Recently, a new questionnaire to evaluate disability in IBD was developed.9 The Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Disability Score (IBD-DS) comprises the following domains: mobility, self-care, major daily life activities, gastrointestinal-related problems, mental health and interaction with the environment. During the initial evaluation,9 the questionnaire seemed to be sufficiently valid and useful for evaluation of disability in IBD, however, for a more widespread use its validation in more studies is necessary, particularly in different countries and ethnicities. Thus the aim of our study was not only to translate to Portuguese the IBD-DS but also to apply and validate it in Portuguese patients.

2Methods2.1Inflammatory Bowel Disease Disability Score – QuestionnaireThe IBD-DS, a tool for assessing disability reported by patients, comprises a total of 58 questions grouped into 6 domains. Fifty-four questions were scored according to a 5-point Likert scale (1 – no limitation; 2 – slight limitation, 3 – moderate limitation, 4 – severe limitation, 5 – worst limitation) and four questions were a choice between a yes or no answer.

2.2Translation and cross-cultural adaptationThe initial translation of the questionnaire (in English) to the target language (Portuguese) was performed by two bilingual translators (Portuguese and English). The translators were previously informed about the objectives and underlying concepts of the study, and did not maintain any contact during the process of translation. Two independent translations were obtained. A committee composed by two gastroenterologists, with high fluency in English language and experienced in following patients with IBD, evaluated the equivalence of content between these versions and the original and did the necessary changes to obtain a preliminary version.

To verify the comprehensiveness of the questionnaire, the preliminary version was filled by a sample of 6 patients. Subsequently, and following the doubts reported by patients, the previously referred committee made the necessary modifications to obtain a final version. (Annex 1).

3PatientsBetween June and November 2013, patients with the diagnosis of IBD (UC or CD), with follow-up in our gastroenterology department, were prospectively interviewed during an attending physician visit. We excluded patients seen in urgent context, hospitalized patients, as well as those unable to comprehend the questionnaire.

The patients were informed about the study's character and those who agreed to participate were enrolled and signed an informed consent form.

Patients were invited to fill the Portuguese version of the IBD-DS and a questionnaire to assess quality of life – the short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (SIBDQ).

Patients’ current disease state, with respect to disease activity, was assessed using the Harvey-Bradshaw (HB) for CD and partial (excluding sigmoidoscopy) Mayo score (pMayo) for UC. Crohn's disease was considered in remission when the HB was <5,10 and UC was considered in remission in patients with a pMayo ≤2 and no subscore >1.11

The study of demographic and clinical variables (disease duration, topography of intestinal lesions, previous surgery or hospitalization related to IBD, extra-intestinal manifestations and medical treatment) was conducted through analysis of medical records from the beginning of the disease until the time of study.

Ninety-six patients with IBD filled the IBD-DS, however 11 (11.4%) were excluded because they were not correctly filled. The 85 questionnaires correctly filled were used to test the validity and internal consistency of the IBD-DS. To study the reproducibility of IBD-DS, within 4 weeks after they completed the IBD-DS, a subset of 17 patients were asked to fill the IBD-DS again (test/retest reliability).

4Statistical analysisUsing the Gpower® software and taken into consideration the statistical tests employed, we determined the minimum sample size to be hundred eighteen patients.

The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS – Statistical Package for the Social Sciences – version 21.0. The statistical level of significance (α) was established at 5%.

Descriptive data were described as mean±standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables and proportions for qualitative ones.

Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation between the IBD-DS and SIBDQ.

The Student's t-test for independent samples was used to compare the mean of IBD-DS between active and inactive disease.

To compare the means IBD-DS for variables age at diagnosis and topography of intestinal lesions was used the analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) and for gender, history of previous surgery or hospitalization, extra-intestinal manifestations and employment status was used the t-test for independent samples.

The internal consistency of the IBD-DS was measured with Cronbach's alpha coefficient and the reproducibility was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Alpha values≥0.7012 and an ICC≥0.7013 were considered appropriate.

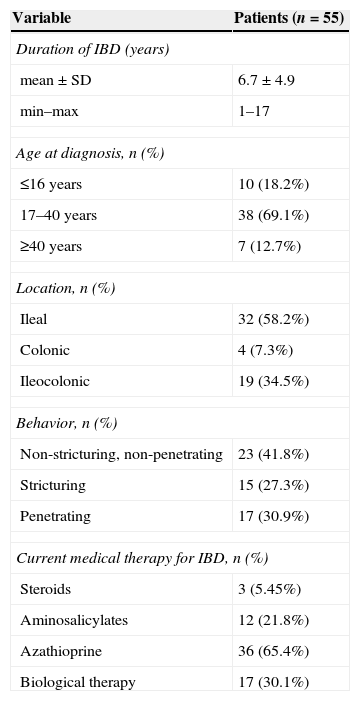

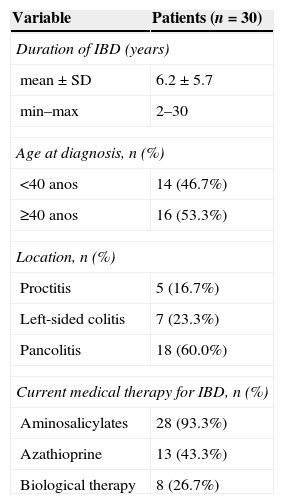

5Results5.1PatientsThe study population included 55 patients with CD and 30 with UC, 53 (62.4%) females, with a mean age of 39.3±12.3 years (17–77 years). The 55 patients with CD included in the study had a mean age of 38.6±11.9 years (17–77 years) and 36 (65.5%) were female. The 30 patients with UC included in the study had a mean age of 40.6±13.3 years (19–65 years) and 17 (56.7%) were female. Twenty-seven patients (31.8%), all with CD, had a previous surgery related to IBD, one of them with an ileostomy. Seven patients (8.2%), all with CD, had a history of perianal disease. Forty-seven patients (55.3%), 40 with CD and 7 with UC, had a previous hospitalization related to IBD.

Eight patients (9.4%), 4 with CD and 4 with UC, were currently under a sick leave and 9 (10.6%) patients with CD were on a disability pension.

The clinical details of patients with CD or UC are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Clinical characteristics of Crohn's disease patients.

| Variable | Patients (n=55) |

|---|---|

| Duration of IBD (years) | |

| mean±SD | 6.7±4.9 |

| min–max | 1–17 |

| Age at diagnosis, n (%) | |

| ≤16 years | 10 (18.2%) |

| 17–40 years | 38 (69.1%) |

| ≥40 years | 7 (12.7%) |

| Location, n (%) | |

| Ileal | 32 (58.2%) |

| Colonic | 4 (7.3%) |

| Ileocolonic | 19 (34.5%) |

| Behavior, n (%) | |

| Non-stricturing, non-penetrating | 23 (41.8%) |

| Stricturing | 15 (27.3%) |

| Penetrating | 17 (30.9%) |

| Current medical therapy for IBD, n (%) | |

| Steroids | 3 (5.45%) |

| Aminosalicylates | 12 (21.8%) |

| Azathioprine | 36 (65.4%) |

| Biological therapy | 17 (30.1%) |

Clinical characteristics of ulcerative colitis patients.

| Variable | Patients (n=30) |

|---|---|

| Duration of IBD (years) | |

| mean±SD | 6.2±5.7 |

| min–max | 2–30 |

| Age at diagnosis, n (%) | |

| <40 anos | 14 (46.7%) |

| ≥40 anos | 16 (53.3%) |

| Location, n (%) | |

| Proctitis | 5 (16.7%) |

| Left-sided colitis | 7 (23.3%) |

| Pancolitis | 18 (60.0%) |

| Current medical therapy for IBD, n (%) | |

| Aminosalicylates | 28 (93.3%) |

| Azathioprine | 13 (43.3%) |

| Biological therapy | 8 (26.7%) |

For patients with CD, the mean values of quality of life and disability, assessed by SIBDQ and IBD-DS, were 44.8±11.9 and 101.6±30.1, respectively.

The quality of life in patients with CD showed a strong negative correlation with the IBD-DS (r=−0.858, p<0.001).

Patients’ current disease state, with respect to disease activity, assessed using the Harvey–Bradshaw (HB), showed that 37 (67.3%) patients with CD were in clinical remission.

There was a statistically significant difference of the mean of IBD-DS between inactive vs. active disease (93.78±24.09 vs. 11.757±35.37, p=0.016).

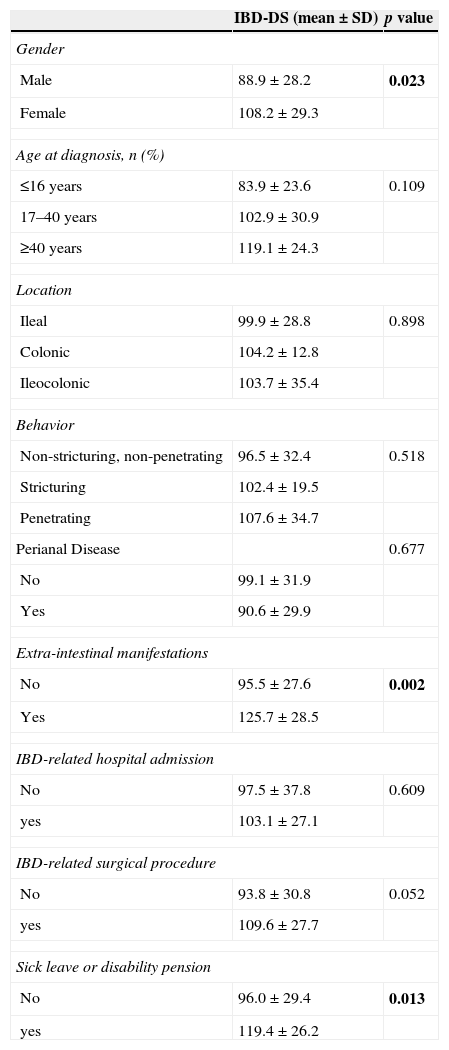

In patients with CD, the study of clinical variables also showed significantly higher scores of disability in women (p=0.023) and patients with extra-intestinal manifestations of CD (p=0.002). Patients with a sick leave or disability pension also had significantly higher disability scores (p=0.013). There were no statistically significant difference between the mean values of the IBD-DS and the age at diagnosis (p=0.109), location (p=0.898) and disease behavior (p=0.518), perianal disease (p=0.677), hospitalization (p=0.609), or IBD-related surgical procedure (p=0.052) (Table 3).

Mean of IDB-DS for clinical variables in Crohn's disease patients.

| IBD-DS (mean±SD) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 88.9±28.2 | 0.023 |

| Female | 108.2±29.3 | |

| Age at diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| ≤16 years | 83.9±23.6 | 0.109 |

| 17–40 years | 102.9±30.9 | |

| ≥40 years | 119.1±24.3 | |

| Location | ||

| Ileal | 99.9±28.8 | 0.898 |

| Colonic | 104.2±12.8 | |

| Ileocolonic | 103.7±35.4 | |

| Behavior | ||

| Non-stricturing, non-penetrating | 96.5±32.4 | 0.518 |

| Stricturing | 102.4±19.5 | |

| Penetrating | 107.6±34.7 | |

| Perianal Disease | 0.677 | |

| No | 99.1±31.9 | |

| Yes | 90.6±29.9 | |

| Extra-intestinal manifestations | ||

| No | 95.5±27.6 | 0.002 |

| Yes | 125.7±28.5 | |

| IBD-related hospital admission | ||

| No | 97.5±37.8 | 0.609 |

| yes | 103.1±27.1 | |

| IBD-related surgical procedure | ||

| No | 93.8±30.8 | 0.052 |

| yes | 109.6±27.7 | |

| Sick leave or disability pension | ||

| No | 96.0±29.4 | 0.013 |

| yes | 119.4±26.2 | |

For patients with UC, the mean values of quality of life and disability, assessed by SIBDQ and IBD-DS, were 49.1±13.6 and 92.5±34.2, respectively.

The quality of life in patients with UC showed a strong negative correlation with the IBD-DS (r=−0.933, p<0.001).

Patients’ current disease state, with respect to disease activity, assessed using the pMayo score, showed that 23 (76.7%) patients with UC were in clinical remission.

There was a statistically significant difference of the mean of IBD-DS between inactive vs. active disease (78.96±24.51 vs. 137.14±20.58, p<0.001).

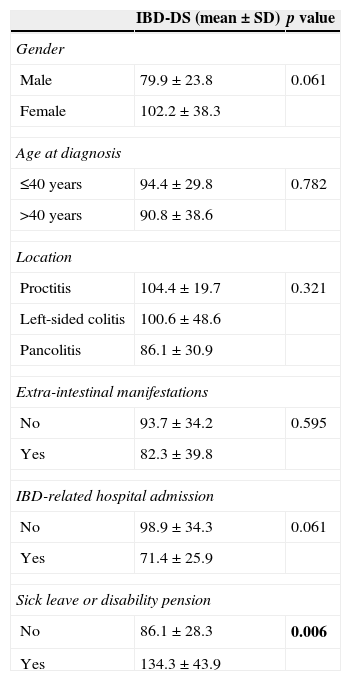

Patients with a sick leave or disability pension had significantly higher disability scores (p=0.006). There was no statistically significant difference between the mean values of the IBD-DS and gender (p=0.061), age at diagnosis (p=0.782), extent of disease (p=0.321), presence of extra-intestinal manifestations (p=0.595) or previous IBD-related hospital admission (p=0.061) (Table 4).

Mean of IDB-DS for clinical variables in ulcerative colitis patients.

| IBD-DS (mean±SD) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 79.9±23.8 | 0.061 |

| Female | 102.2±38.3 | |

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| ≤40 years | 94.4±29.8 | 0.782 |

| >40 years | 90.8±38.6 | |

| Location | ||

| Proctitis | 104.4±19.7 | 0.321 |

| Left-sided colitis | 100.6±48.6 | |

| Pancolitis | 86.1±30.9 | |

| Extra-intestinal manifestations | ||

| No | 93.7±34.2 | 0.595 |

| Yes | 82.3±39.8 | |

| IBD-related hospital admission | ||

| No | 98.9±34.3 | 0.061 |

| Yes | 71.4±25.9 | |

| Sick leave or disability pension | ||

| No | 86.1±28.3 | 0.006 |

| Yes | 134.3±43.9 | |

There was no difference between the mean of the IBD-DS for CD and UC (92.5±34.2 vs. 101.6±30.1, p=0.212).

5.4IBD-DS – internal consistency and reproducibilityThe IBD-DS presented a high degree of internal consistency (coefficient alpha: 0.85) and a good reproducibility (ICC=0.76, 95% 0.34–0.91).

6DiscussionOver the last decades, the incidence and prevalence of IBD has been increasing in Europe, and an estimate 0.3% of the European population suffers from IBD.14 In Portugal, a recent study, based on a pharmacoepidemiological approach, estimated an increased prevalence of CD and UC of 42 and 43 per 100,000 in 2003 to 71 and 73 in 2007, respectively.15 This increase in incidence and prevalence accounts for substantial costs to the health care system and society.

The impact of IBD in all domains of the patient's life is substantial because it is a chronic disease, with an early age onset and a relapsing-remitting course. However, when compared with other chronic inflammatory diseases, such as multiple sclerosis,16 it is surprising how little is known about disability in IBD.

A new tool to assess disability in IBD was recently developed.9 During the validation of the score, by the same working group, this proved to be sufficiently sensitive to detect disability in patients with IBD.

The assessment of disability in Portuguese patients with IBD is crucial to provide a more holistic approach to the patient. However, the simple translation of a questionnaire to another language does not guarantee its validity and reproducibility, being critical the evaluation of these parameters prior to the widespread application of the questionnaire.

The validity of the Portuguese version of the IBD-DS was assessed by the comparison of the IBD-DS with a questionnaire to assess quality of life of IBD patients, the SIBDQ, a tool sufficiently comprehensive and easy to apply.17 We observed a significant negative correlation between the IBD-DS and the SIBDQ (r=−0.858 and r=−0.933, p<0.001, for CD and UC, respectively), suggesting that a lower quality of life correlated with a higher IBD-DS. These findings are corroborated by the study of Allen et al. (r=−0.838, p<0.001).9 Other studies further support the relationship between quality of life and work disability.6–8

During the validation of IBD-DS, we also included the assessment of disease activity. In the study by Allen et al.9 a significant relationship between the activity of CD, assessed by Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI), and the IBD-DS was observed. In our study, we chose to use the HB index for assessing activity in DC, because it is easier to apply and has a strong correlation with the CDAI,10 and we showed a statistically significant difference of the mean of IBD-DS between inactive vs. active disease. We also showed a significant relationship between the activity of UC and IBD-DS, not observed by Allen et al,9 allowing us to enhance the applicability of IBD-DS in patients with UC.

Recently, another measure to assess disability in IBD was developed. This new tool, called IBD-disability index,18 comprises the categories of the “International Classification Functioning”19 that more often are affected in patients with IBD. However, at the time of our study, the IBD-disability index had not yet been validated in patients with IBD.

Furthermore, we also studied variables related to IBD with potential impact on disability. Some studies have reported that CD carries a greater risk of disability than ulcerative colitis.20,21 In our study, there was no statistically significant difference in the IBD-DS scores between these two groups of patients. However, in CD, unlike UC, multiple clinical variables, including gender and the presence of extra-intestinal manifestations, correlated significantly with disability. The data concerning the influence of gender on disability are still contradictory. Although, some studies show no differences,22 others have found a significant relationship with the female gender.6,8 Several hypotheses for this finding are frequently reported in studies. Psychosocial factors and coping strategies may play a role in how women deal with the disease.23 Furthermore, women have greater disease-related concerns and worries about being treated differently as a result of their disease,24 and are also more likely to report concerns related to attractiveness and body Image.25,26 The presence of extra-intestinal manifestations7,20 was also previously associated with a greater likelihood of temporary or permanent work disability. The IBD affects not only the ability to work, but other important domains of patients’ life. In this context, the fact that variables previously known as predictors of work disability remained significantly related to disability assessed by IBD-DS, emphasizes the importance of the latter in the overall assessment of disability in patients with IBD.

Unsurprisingly, CD and UC patients with a sick leave or disability pension had significantly higher disability scores. As previously reported, most disability studies have traditionally focused on work and employment. A recent European survey,14 presented by the European Federation of Crohn's & Ulcerative Colitis Associations (EFCCA) in partnership with the European Crohn's and Colitis Organization (ECCO), assessed burden of IBD in Europe. About half of the patients responded that their life was significantly affected by IBD during their most recent flare-up. Of these, 26% had more than 25 days of annual absence due to IBD. The social and economic impact of disability in IBD patients is colossal, as it is estimated that 20% of patients will eventually receive a disability pension and over 10–25% will face unemployment.

In this topic, the comparison between studies is difficult due to the different socio-economic factors and governmental regulations that determine the qualifications for a sick leave or a disability pension, from country to country. Thus, the use of IBD-DS, a standard measure to quantify disability in IBD, will allow a more uniform and objective assessment of disability in IBD, allowing the comparison of results between different institutions and different countries.

In conclusion, the Portuguese version of the IBD-DS is a valid and easily applicable instrument, thereby making it a useful tool in the evaluation of disability in IBD. The application of a standard measure for evaluating disability in IBD is of great interest, as it will allow for a better perception of the impact of disease in the patient's life and an objective assessment of disability for the qualification of patients for a sick leave or a disability pension as well as adding a new dimension to the assessment of response to therapy.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank the teachers José Moniz and Ana Paula Catanho for their collaboration in the translation of the questionnaire.