Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) is an extremely rare extra-nodal lymphoma with a poor prognosis. The World Health Organization (WHO)1 classifies it into 2 types: type I is associated with coeliac disease and is more common, while type II is very rare in Western countries and is not related with coeliac disease. Unlike type I, type II is characteristically positive for CD8 and CD56 and shows clonal T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement.2,3 Type II, being highly aggressive, commonly presents as intestinal perforation.

We evaluated a patient without gluten intolerance with a type II EATL that commenced as symptomatic of acute surgical abdomen.

A 58-year-old man with a history of weight loss (11kg in 2 months) attended the emergency department for symptoms of sharp abdominal pain that commenced 1h previously. On examination he presented signs of generalized peritoneal irritation.

Blood tests revealed elevated C-reactive protein 16.6mg/l (normal<10mg/L), lactate 1.8mmol/L and white cells 12.3×109/L (normal 11×109/L) with 72.5% neutrophils (normal<70%).

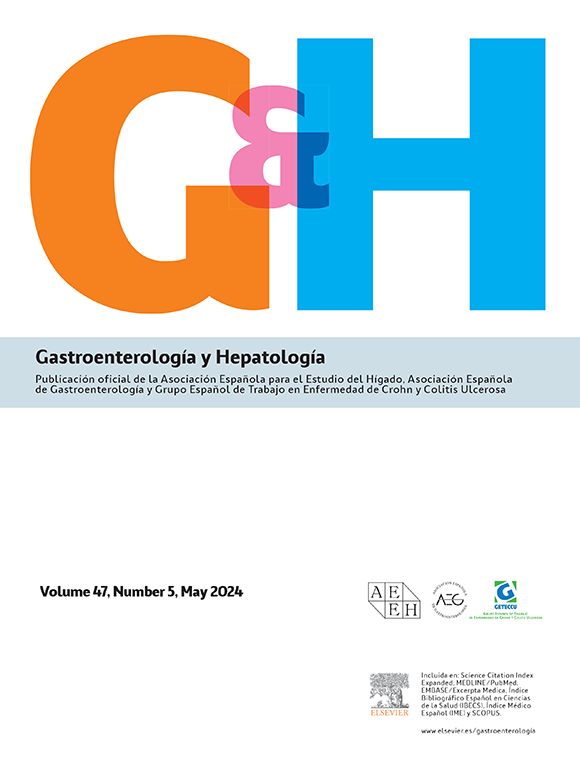

Computed tomography (CT) supported the suspicion of perforation of hollow viscera due to a possible ileal tumour and indicated urgent surgical treatment (Fig. 1A and B). The presence of a whitish ileal nodule measuring 5cm×3cm was observed intraoperatively, together with an adjacent intestinal perforation (Fig. 1C). Approximately 30cm of bowel was resected, along with its mesentery and part of the greater omentum.

(A) Abdominal computed tomography (CT), axial slice: thickening of an ileal loop localized in the right iliac fossa causing closed-loop bowel dilatation. (B) Abdominal CT, coronal slice: pneumoperitoneum and interloop free fluid. (C) Surgical specimen: ileal segment with perforation partially contained by the greater omentum.

Histological study showed monomorphous lymphoid proliferation extending from the mucosa, with infiltration of the crypts to the perivisceral fat, and invasion of the entire wall (Fig. 2A and B). The lymphocytes were small to intermediate in size, with scant cytoplasm and inconspicuous nucleoli (Fig. 2C); there was no accompanying inflammatory component and large cells were absent. Immunohistological study revealed expression of cytotoxic T-lymphoid markers (CD3, CD7, CD8, CD56) (Fig. 2D), but no expression of CD4, CD20, CD5, CD30, CD23, cyclin D1, bcl-2, bcl-6, SOX11 or EBER. The proliferation index was very high (Ki-67, 80%) (Fig. 2E). An increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes was observed in the adjacent ileal mucosa, with no villous atrophy. The resected lymphadenopathies were reactive in nature. A molecular study showed monoclonal TCR gamma rearrangement that confirmed the T type (Fig. 2F).

Histopathology in World Health Organization type II enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. (A) Transmural infiltration of the ileal wall by dense lymphocytic infiltrate (haematoxylin and eosin [H&E], 40×). (B) Invasion of lamina propria of the mucosa and epithelium of the crypts by lymphoid infiltrate (H&E, 200×). (C) Monomorphous lymphoid population of small atypical lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm (H&E, 400×). (D) Immunoexpression of CD3 (200×). (E) Immunoexpression of Ki-67 (80%) (200×). (F) Monoclonal T-cell receptor gamma rearrangement.

These histopathology findings, together with the absence of coeliac disease, established our diagnosis of intestinal EATL (WHO monomorphous variant type II).

The patient received 6 cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristin, and prednisone) chemotherapy and was disease-free at 12 months.

EATL is a primary extra-nodal lymphoma, with origin in the intraepithelial lymphocytes of the intestinal mucosa. In 1937, Fairley and Mackie4 described the presence of intestinal lymphoma in patients with coeliac disease. In 1986, O’Farrelly et al.5 coined the term enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. EATL accounts for fewer than 10–20% of gastrointestinal tract lymphomas2; annual incidence in Western countries is 0.5–1 per million people.6 It is usually diagnosed at around 60 years of age, with no differences between sexes.7 The most common location is at the level of the proximal jejunum, followed by the rest of the small intestine, stomach, colon and rectum.2

Around 2–3% of coeliac patients develop intestinal lymphoma, 65% of which are of T-cell origin.8 The WHO1 classifies EATL into two types. Type I comprises 80–90% of cases, is associated with refractory coeliac disease and is common in Northern Europe. Type II accounts for 10–20% of cases, is not associated with coeliac disease, occurs sporadically and is more common in Asian countries.3 This type is characterized by monomorphous proliferation of small-to-medium sized T-lymphocytes, with no associated inflammatory component. The immunophenotype is distinctive (CD3+, CD4−, CD8+ and CD56+).1 Type I generally does not express CD8 or CD56, the lymphocytes are usually large and inflammatory infiltrates are associated with histiocytes and eosinophils.3

The differential diagnosis of intestinal T-cell lymphomas should include, in addition to EATL types I and II, primary intestinal T/NK-cell lymphoma (nasal type). This aggressive extra-nodal lymphoma is usually associated with vascular invasion and necrosis. The histopathological characteristics that enable differentiation are expression of T-cell markers CD2, cytoplasmic CD3 and CD56, and negativity of markers CD8, CD56 and monoclonal TCR. Given the implication of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) in the aetiopathogenesis of primary intestinal T/NK-cell lymphoma (nasal type), EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) in situ hybridization should be performed.8

Almost half of patients begin with symptoms of acute abdomen, either due to bowel obstruction or perforation. In the remaining patients it presents in the form of abdominal pain associated with weight loss.2 The overall 5-year survival rate is less than 20% in patients with disseminated disease (which mainly affects the liver, spleen or skin),9,10 but as high as 60% in localized disease.2

These tumours are characterized by both high chemoresistance and high recurrence. Treatment is by chemotherapy, and although traditionally based on the administration of anthracyclines only, more aggressive regimens are now implemented, followed by autologous bone marrow transplants.2,8 Surgery is reserved for cases of intestinal perforation, resection of lesions that lead to obstructive symptoms, diagnostic doubts, tumour debulking and lesions that might produce visceral perforations prior to chemotherapy.10 To ensure correct staging, the intestinal tumour with its adjacent mesentery should be resected.

Type II EATL is a very rare lymphoma in our setting that can commence with symptoms of acute abdomen in patients without previous intestinal symptoms. Although surgery is no longer the treatment of choice, it can help patient recovery.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

We would like to thank Dr Jerónimo Forteza Vila of the Valencian Institute of Pathology for performing the molecular study.

Please cite this article as: Payá Llorente C, Pérez Ebri ML, Gómez Abril SÁ, Martínez López E, Richart Aznar JM, Garrigós Ortega G, et al. Perforación intestinal secundaria a linfoma T entérico en un paciente sin intolerancia al gluten. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:331–334.

![Histopathology in World Health Organization type II enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. (A) Transmural infiltration of the ileal wall by dense lymphocytic infiltrate (haematoxylin and eosin [H&E], 40×). (B) Invasion of lamina propria of the mucosa and epithelium of the crypts by lymphoid infiltrate (H&E, 200×). (C) Monomorphous lymphoid population of small atypical lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm (H&E, 400×). (D) Immunoexpression of CD3 (200×). (E) Immunoexpression of Ki-67 (80%) (200×). (F) Monoclonal T-cell receptor gamma rearrangement. Histopathology in World Health Organization type II enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. (A) Transmural infiltration of the ileal wall by dense lymphocytic infiltrate (haematoxylin and eosin [H&E], 40×). (B) Invasion of lamina propria of the mucosa and epithelium of the crypts by lymphoid infiltrate (H&E, 200×). (C) Monomorphous lymphoid population of small atypical lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm (H&E, 400×). (D) Immunoexpression of CD3 (200×). (E) Immunoexpression of Ki-67 (80%) (200×). (F) Monoclonal T-cell receptor gamma rearrangement.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/24443824/0000003900000005/v3_201605230804/S2444382416000365/v3_201605230804/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)