The study's main aim was to determine which formal aspects of psychotherapy (therapist's work experience, number of sessions held, frequency of meetings, length of sessions) contributed to the quality of the therapeutic (working) alliance. The alliance was also analyzed for demographic variables.

MethodsThe sample consisted of 428 participants, and the working alliance was evaluated in 262 psychotherapist–patient dyads. To assess its quality, the author used the full version of the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI).

ResultsThe analyzes led to several conclusions. Their results indicate that the quality of working alliance increases if psychotherapy is conducted by an experienced specialist, if the frequency of sessions is high, and if the sessions are longer. They do not, however, pinpoint the demographic markers of therapeutic alliance quality.

ConclusionThe formal aspects of the psychotherapeutic process influence the quality of the working alliance. Alliance develops to an equal degree in people of different ages and with diverse levels of education, regardless of the presence or absence of close interpersonal relationships in their lives.

Although some authors argue that there is no sufficient evidence to identify the mechanisms and factors responsible for the success of psychotherapeutic treatment,1,2 many studies point to the therapeutic alliance as one of the key factors ensuring positive outcomes of psychotherapy.3,4 The very concept of the therapeutic relationship is currently among the most intensively explored constructs in psychotherapy-related literature.5,6

Factors promoting alliance qualityThe relationship in the psychotherapist–patient dyad, referred to in the literature as the patient–therapist match,7 therapeutic partnership,8 or therapeutic alliance,9 is considered an active factor in effective intervention because it enables the therapist to build a secure framework for various techniques and methods of work. The treatment-dynamizing effect of this factor rests on a certain level of what can be called intimacy between the psychotherapist and the patient. Developed thanks to the alliance, this intimacy allows the therapist to establish permanent communication with the stable part of the patient's personality and helps the patient strive for the expected change despite the fluctuation of perceived tensions and difficulties in functioning. A strong alliance also enables the therapist to adapt to those characteristics of the patient that would otherwise hinder optimal contact.10

Because alliance is regarded as a factor significant to the success of the psychotherapeutic process, attention is devoted mostly to its associations with the outcomes of psychotherapy, especially those measured using objective indicators, such as a decrease in symptoms impairing optimal functioning.11 There is, however, little empirical material concerning what factors alliance quality itself depends on and what it is differentiated by.

The largest number of studies are devoted to the basic conditions responsible for the formation of the alliance. On the therapist's side, the factors most often mentioned as conducive to a proper therapeutic relationship include attitude toward patients, self-awareness regarding one's development (abilities and limitations), and professionalism. Some studies concern the relations of the alliance to psychotherapists’ education, work experience, and qualifications (i.e., the number of training courses and certificates).12,13 In a study devoted to building the therapeutic alliance in the early stage of psychotherapy (during the first sessions), Sexton and colleagues14 established that alliance quality decreased when psychotherapists were less engaged in the current conversation with their patients, when what they said was devoid of emotional content, and when they were giving general advice and information.

Horvath15 found that, on the patient's side, the main factors influencing the quality of the therapeutic alliance were the patient's basic willingness to cooperate and a more mature personality structure based on optimal attachment models. Studies show that patients’ earlier life experience, quality of object relations, and pre-therapeutic interpersonal functioning may impact the alliance too.16,17 Still, some factors require further research and exploration.

Scholars have investigated the impact of variables such as the form of psychotherapy (face-to-face vs. online) on alliance quality. According to preliminary results, the evaluations of the alliance made by patients attending online psychotherapy did not differ from those made by clients attending in-office sessions. Psychotherapists’ evaluations of alliance varied, being higher in the case of online psychotherapy.18 In the latest studies, it is underscored that the evaluation of alliance generally differs between patients and psychotherapists.19,20 The psychotherapist's and the client's evaluations do not necessarily coincide, particularly in the early stage of treatment.21

The findings concerning the differentiation of alliance quality depending on the length of the psychotherapeutic process also vary. There are studies indicating that the strength of the alliance remains stable during the psychotherapeutic process.22,23 In a study on short-term individual therapy, Sexton et al.24 found that alliance was established after the end of the first session and remained relatively stable for 10 sessions. As opposed to studies suggesting its stability, other research showed that alliance tended to become stronger during treatment.25 Still other authors reported evidence that alliance quality fluctuated in unique ways in different patient-psychotherapist dyads26 or that it increased with an increase in the number of sessions held.5,27 It was also reported that, with the development of personal bonds in the dyad, the relationship of cooperation became stronger.28,29

Interestingly, several alliance development patterns have been described in the literature. For instance, Kramer, de Roten, Beretta, Michel, and Despland30 distinguished three groups with different patterns: a group in which the alliance increased as the treatment progressed, a group in which it remained stable during treatment, and a group in which it deteriorated with time. In the case of very short psychotherapies, consisting of four sessions, research revealed U-shaped alliance development patterns, with high initial evaluations decreasing in the middle of treatment and then rising again during the final session.31 In most studies to date, the alliance was evaluated only in the early phase of psychotherapy.32

Bordin's pantheoretical conception of allianceOne of the main and most widely known theories of alliance in psychotherapy is the one proposed by Bordin.33,34 In Bordin's theory, the therapeutic relationship, referred to as the working alliance, is a pantheoretical variable that can be analyzed regardless of the theoretical modality employed by the psychotherapist. This important assumption makes it possible to compare the quality of alliance across psychotherapeutic modalities.

Bordin's model presupposes cooperation and communication. The patient and the psychotherapist do not differ in terms of competence in evaluating the way of bringing about a specific change through psychotherapy and the quality of that change. Recovery takes place through the achievement of goals (the cognitive component of alliance) and tasks (the behavioral component) agreed on. What enables agreement on goals and tasks and makes their effective accomplishment possible is the developing bond (the affective component of the alliance)—a feeling that one is accepted, understood, and liked.35 The first two dimensions are specified usually, though not exclusively,36 during the first meetings—which, for the psychotherapist, are also sessions devoted to the assessment of the patient's health problem. The third dimension is developed throughout the psychotherapeutic process, as it is not possible to agree on mutual trust during the first sessions.

Bordin stresses that the quality of mutual agreement is the main component of treatment effectiveness and patient recovery. This is because the alliance facilitates the therapist's work using specific techniques and ensures the patient's openness to the proposed treatment.

The present studyThe empirical material accumulated so far in systematic research on how the quality of psychotherapeutic alliance depends on variables defining the psychotherapeutic process encourages further explorations and analyzes in this area. Knowledge on this issue seems to be far from complete, particularly in Poland, where the quality of the working alliance is evaluated much less often than elsewhere. The usually considered factors belong to the categories of personal skills, patients’ motivations, and the level of or decrease in the symptoms experienced by patients.

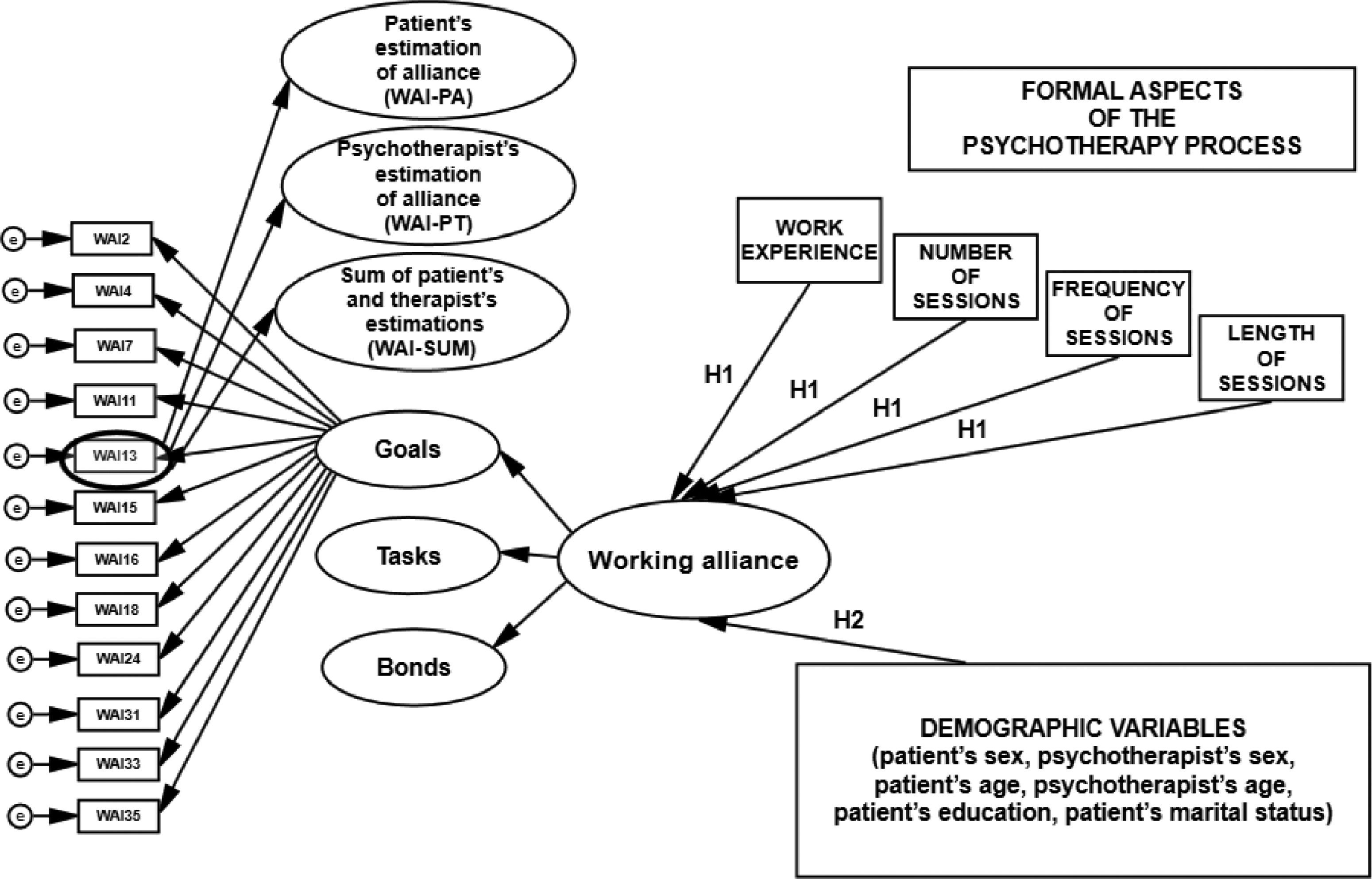

The main aim of the present study was to determine which formal aspects of the psychotherapy process (psychotherapist's work experience, number of sessions, frequency of meetings, length of sessions) influenced the therapeutic alliance.

The working alliance was also analyzed in terms of demographic variables (patient's and psychotherapist's sex and age, patient's education, and patient's marital or relationship status). I formulated the following hypotheses:

H1: The psychotherapist's longer work experience, a higher number of sessions held in the psychotherapeutic process, a higher frequency of meetings, and a longer duration of sessions increase the quality of the working alliance in psychotherapy.

H2: The psychotherapist's and the patient's age and sex, the patient's education, and the patient's marital status differentiate the quality of the working alliance in psychotherapy.

When investigating the effect of the formal factors defining the psychotherapeutic process on the quality of the therapeutic alliance, I also considered the source of information about alliance quality. I relied not only on separate evaluations from patients and psychotherapists but also on combined (aggregated) patient and psychotherapist evaluations.

The model of hypothesized relationships among the variables, verified based on empirical data, is shown in Fig. 1.

MethodParticipantsA total of 440 individuals were deemed eligible and invited to take part in the study: 270 patients and 170 psychotherapists. The final sample consisted of 428 subjects who consented to participate: 262 patients and 166 psychotherapists. The dropout rate was 0.029 (2.9%) for patients and 0.023 (2.3%) for therapists.

The working alliance was assessed in 262 psychotherapist–patient dyads. The study included 428 participants. Among them, there were 262 patients: 132 women aged 14 to 80 years (M = 35.23, SD = 11.89) and 130 men aged 18 to 70 years (M = 37.24, SD = 9.93). Most of the patients had higher (54.6%) or secondary education (42.75%) and lived in cities with a population above 100,000 (61.4%). In the sample of patients, 93 participants (35.5%) were single and 169 (64.5%) were married or had a romantic partner.

The sample also included 166 psychotherapists: 111 women and 55 men, aged 27 to 64 years (M = 42.9, SD = 9.04). Among the psychotherapists, 90.8% had a master's degree and 9.2% had a doctoral degree; 66.8% had completed at least two years of training in psychotherapy; 52.7% had a certificate from one of the Polish psychotherapeutic associations. Nearly 53% of psychotherapists had more than 5 years of work experience, and 40% had worked in this profession for 1 to 5 years.

Psychotherapy followed the principles of several orientations: psychoanalytic and psychodynamic (25.6%), cognitive-behavioral (30.9%), jointly considered Ericksonian (12.2%), and systemic (11.5%), Gestalt (8.8%), humanistic (4.2%), and other (e.g., existential; 0.4%).

By the time of the measurement, the patients had attended between 2 (1.1%) and 960 (0.4%) sessions (M = 36.23, SD = 81.07). Two hundred participants (76.3%) attended psychotherapy once a week, 10.7% of psychotherapies (n = 28) involved sessions held twice a week, and 8.8% of dyads (n = 23) attended sessions once a fortnight. Most psychotherapy sessions (76.7%) took 50 to 60 min.

As regards the ailments that patients were treated for, the largest group was individuals diagnosed with affective and mood disorders (32.8%). Mental and behavioral disorders caused by alcohol and substance use were diagnosed in 23.3% of patients, and adaptation disorders were found in 13.4% of cases; 9.5% of psychotherapies were conducted due to personality disorders, schizophrenia, schizotypal disorders, and delusional disorders. In 7.6% of patients, the reported reason for psychotherapeutic work was anxiety disorders and phobias, and 1.1% needed treatment due to a trauma experienced in the pretherapeutic period.

ProcedureEmpirical research was conducted between 2019 and 2020. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. Participants for the main study were recruited from public and private psychotherapy offices across Poland, with most voivodeships (administrative regions) represented in the sample. The research procedure was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Maria Grzegorzewska University (APS) in Warsaw (decision no. 169-2018/2019).

First, the researcher approached the psychotherapist about participation in the study. After the psychotherapist granted his or her preliminary consent, both participants—the psychotherapist and the patient—were informed about the purpose of the study and asked for their final consent to take part in it. Both the patient and the psychotherapist gave informed written consent to participate. Next, the psychotherapist completed the Working Alliance Inventory and a survey on demographic variables and the formal aspects of psychotherapy.

In the patient's case, measurement began with the Working Alliance Inventory, followed by a survey with questions about sociodemographic variables. I analyzed data collected in a single measurement. The respondents received no remuneration for participation in the study. After completing the questionnaires, each participant was asked if he or she had responded to all items in the set of measures. No missing data were found.

MeasuresThe Working Alliance Inventory (WAI). To assess the quality of the working alliance, I used the full version of the WAI37 as adapted and validated into Polish.38 There are two versions of this inventory, designed to be completed by the patient (WAI-PA) and by the psychotherapist (WAI-PT). Each version consists of 36 analogous items operationalizing the construct of working alliance, which the respondent rates on a Likert scale as accurately or inaccurately describing the cooperation in the patient–psychotherapist dyad being evaluated. The WAI score can be computed for three subscales: Goals, Tasks, and Bonds; it is also possible to determine overall alliance quality by computing the total score. Each subscale is composed of 12 items: 6 positive and 6 negative. The reliability coefficients for the total score are αWAI-PA = .97 and αWAI-PT = .97, and the reliability values for the subscales are as follows: αWAI-PA = .93 and αWAI-PT = .92 for Goals, αWAI-PA = .93 and αWAI-PT = .92 for Tasks, and αWAI-PA = .93 and αWAI-PT = .94 for Bonds. In this study, reliability was also computed for the sum of the patient's and the psychotherapist's scores (WAI-SUM); its value for the total score is αWAI-SUM = .98, while reliability values for the subscales are: αWAI-SUM = .95 for Goals, αWAI-SUM = .95 for Tasks, and αWAI-SUM = .96 for Bonds. WAI-SUM is a new proposal for the operationalization of the working alliance. It is based on the idea of measurement combining patient and psychotherapist evaluations to eliminate the overestimations and underestimations that may appear on either side of the dyad. The score is computed by adding the evaluations made by the patient and the therapist. Measurement using the WAI-SUM was found to be reliable and valid in earlier extensive empirical research validating the inventory.38 Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed that the WAI measurement was valid.

Demographic data and the formal aspects of the psychotherapeutic process. In my study, I administered an elaborate demographic survey to control for demographic variables (sex, age, education) and psychotherapy-related ones (psychotherapist's work experience, number of sessions held, frequency of meetings, length of sessions). Two versions of the survey were prepared: one for patients and the other for psychotherapists. The version completed by psychotherapists included questions about the formal aspects of the psychotherapeutic process.

Statistical methodsI used the SPSS 25 and IBM SPSS AMOS 25 statistical packages. Preliminary analyzes of participants’ sociodemographic data and reliability analyzes were performed using SPSS 25. Analyzes involving tests of differences were also run in SPSS 25. To analyze SEM models, I used the AMOS 25 package.

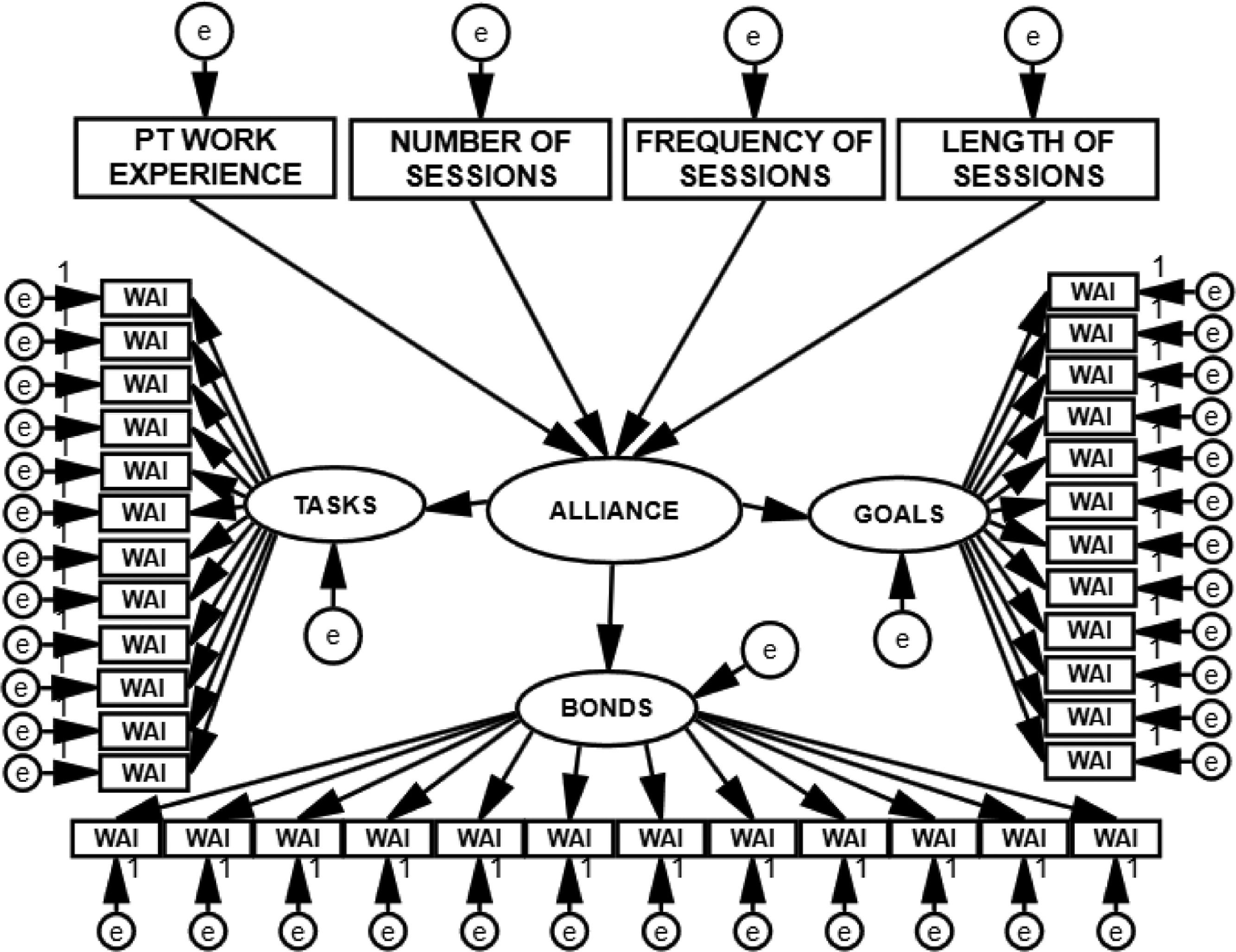

ResultsFormal aspects of psychotherapy and the quality of alliance: SEM structural models of the observable variablesTo test the hypothesis concerning the relations between the formal aspects of the psychotherapeutic process and the quality of working alliance (H1), I built a structural model with eight variables, as illustrated in Fig. 2, and tested it using structural equation modeling (SEM). Because the measurement was based on the patient's evaluation (WAI-PA), the psychotherapist's evaluation (WAI-PT), and combined patient's and psychotherapist's evaluations (WAI-SUM), I constructed three SEM models. Their fit indices are presented in Table 1.

Structural and measurement model with eight variables, postulating the direction of relationships between the variables concerning the formal aspects of the psychotherapeutic process and the quality of alliance, tested with SEM. PT work experience = psychotherapist's work experience in years; the number of sessions = the number of psychotherapeutic sessions the patient has attended by the time of the measurement (min. 2, max. 960); frequency of sessions = the frequency of the patient's attendance at psychotherapeutic sessions (minimum: once a month; maximum: three times a week), length of sessions = the mean duration of a psychotherapeutic session in minutes (min. 30, max. 90).

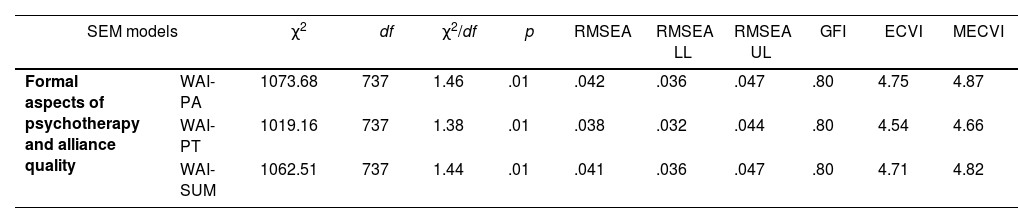

Fit Indices for the Tested Models.

Note. χ2 = chi2 model fit statistic; df = degrees of freedom; χ2/df = chi2 statistic divided by degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; RMSEA LL = lower limit of the value of root mean square error of approximation; RMSEA UL = upper limit of the value of root mean square error of approximation; GFI = goodness-of-fit index; ECVI and MECVI = information criteria used to compare the quality of models.

Using the criteria adopted to assess fit indices39 for SEM models (χ2/df < 2.5; RMSEA ≤.80; GFI values close to or exceeding .90; ECVI and MECVI—the best model is the one with the lowest values) and analyzing the indices reflecting the fit of the theoretical model with a particular measurement model, I found that all three models had very good values of some fit indices (e.g., χ2/df, RMSEA) and narrowly acceptable values of others (e.g., GFI). The information criteria (ECVI, MECVI) indicate that the quality of the models is similar. I therefore decided to determine the strength of relationships between the formal aspects of psychotherapy and the quality of working alliance based on results from all three models. These were not meant to be competing models; instead, I expected that they would all yield comparable results on the hypothesized relationships, thus providing strong empirical evidence to verify them. The values of effect size estimators are presented in Table 2.

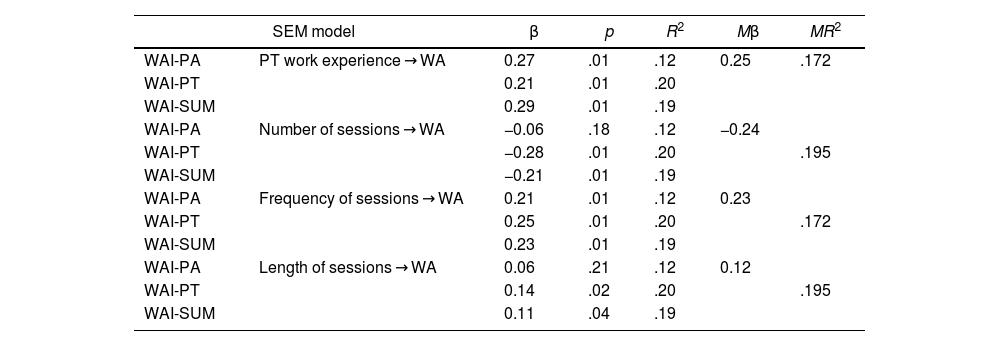

Standard Estimators for the Tested Models.

Note. PT work experience = psychotherapist's work experience in years; the number of sessions = the number of psychotherapeutic sessions the patient has attended by the time of the measurement (min. 2, max. 960); frequency of sessions = the frequency of the patient's attendance at psychotherapeutic sessions (minimum: once a month; maximum: three times a week), length of sessions = the mean duration of a psychotherapeutic session in minutes (min. 30, max. 90), β = standardized path coefficient; R2 = multiple correlation coefficient; Mβ and MR2 = averaged values.

Most factor loadings, indicating how strongly the formal aspects of psychotherapy impact the working alliance, proved to be statistically significant and consistent across different sources of alliance evaluation (patient, psychotherapist, and combined evaluations) in terms of both size and direction.

The effects of the first three factors—psychotherapist's work experience, the number of sessions held, and the frequency of sessions—on the alliance were similar, though rather weak (MβPT WORK EXPERIENCE = 0.25, MβNUMBER OF SESSIONS = −0.24, MβFREQUENCY OF SESSIONS = 0.23). The effect of the length of psychotherapeutic sessions on the working alliance proved to be the weakest (MβLENGTH OF SESSION = 0.12). The models explained an average of 17.2% of the variance in alliance quality as determined by the psychotherapist's work experience or by the frequency of sessions. In the case of the remaining relationships, the models explained an average of 19.5% of the variance in the explained variable.

The results showed that the quality of the working alliance increased if psychotherapy was conducted by an experienced therapist and if the frequency of sessions was high. There was a weak but positive relationship between session length and alliance quality. The analysis revealed an interesting pattern for the number of sessions—alliance quality proved to be inversely related to this variable. In other words, the quality of alliance was not higher at all if the psychotherapeutic process had been longer. The effect sizes were similar regardless of who evaluated the psychotherapeutic alliance.

In sum, the values of coefficients yielded by SEM verified the issue of alliance quality being determined by the formal aspects of psychotherapy. Hypothesis H1 was supported, except for the relationship between alliance quality and the number of sessions held, whose direction was opposite to the postulated one.

Demographic variables and alliance qualityThe psychotherapeutic alliance was analyzed also in terms of demographic variables (H2): sex and age (both patient's and psychotherapist's), patient's education, and patient's marital status (relationship status). To test the differentiating effect of the demographic variables, I performed Student's t-test for independent samples. The results are presented in Table 3.

Differences in the Evaluation of the Therapeutic Alliance According to Demographic Variables.

| DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLE | Alliance | Goals | Tasks | Bonds | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | t | M | SD | t | M | SD | t | M | SD | t | ||

| PA sex | F (n = 132) | 351.86 | 63.52 | −1.528 | 115.29 | 22.32 | −0.840 | 116.25 | 21.71 | −1.498 | 120.33 | 20.86 | −2.171* |

| M (n = 130) | 364.35 | 68.69 | 117.67 | 23.53 | 120.39 | 23.04 | 126.29 | 23.57 | |||||

| PT sex | F (n = 166) | 354.21 | 62.79 | −1.194 | 115.32 | 21.91 | −1.037 | 116.88 | 20.88 | −1.294 | 122.01 | 21.37 | −1.174 |

| M (n = 96) | 364.72 | 71.83 | 118.46 | 24.54 | 120.77 | 24.81 | 125.49 | 24.03 | |||||

| PA age | ≥36 (n = 130) | 357.51 | 65.97 | −0.134 | 116.15 | 22.41 | −0.221 | 118.18 | 22.17 | −0.092 | 123.18 | 22.80 | −0.078 |

| < 36 (n = 132) | 358.61 | 66.88 | 116.78 | 23.49 | 118.43 | 22.78 | 123.39 | 22.09 | |||||

| PT age | ≥ 41 (n = 132) | 359.89 | 70.84 | 0.449 | 116.52 | 24.51 | 0.038 | 118.70 | 23.81 | 0.290 | 124.66 | 23.86 | 1.000 |

| < 41 (n = 130) | 356.21 | 61.57 | 116.42 | 21.27 | 117.9 | 21.02 | 121.89 | 20.81 | |||||

| PA education | secondary (n = 112) | 361.00 | 65.98 | 0.512 | 116.81 | 22.19 | 0.126 | 119.93 | 22.28 | 0.928 | 124.26 | 22.84 | 0.458 |

| higher (n = 143) | 356.71 | 66.70 | 116.45 | 23.65 | 117.29 | 22.68 | 122.97 | 21.84 | |||||

| PA marital status (relationship status) | single (n = 93) | 355.95 | 67.48 | −0.382 | 114.92 | 23.25 | −0.809 | 117.73 | 23.12 | 0.489 | 123.29 | 22.30 | 0.002 |

| in a relationship (n = 169) | 359.22 | 65.83 | 117.32 | 22.75 | 118.62 | 22.11 | 123.14 | 22.52 | |||||

Note. Alliance = total score on the Working Alliance Inventory; Goals = Agreement on Goals subscale; Tasks = Agreement on Tasks subscale; Bonds = Development of Bonds subscale; PA sex = patient's sex; PT sex = psychotherapist's sex; PA age = patient's age; PT age = psychotherapist's age; PA education = patient's education; PA marital status = whether the patient lives alone or whether he/she is married or in a romantic partner; M = arithmetic mean; SD = standard deviation, t = Student's t-test for independent samples.

The results of analyzes show that the therapeutic alliance is not differentiated by demographic variables. The patient's and the psychotherapist's sex and age, the patient's education, and the patient's marital status do not determine working alliance evaluations. This applies not only to the overall evaluation of the alliance but also to its dimensions: goals, tasks, and bonds.

It makes no difference for the quality of the alliance established during the psychotherapeutic process if the individuals involved—patient and psychotherapist—are male or female. Nor does alliance quality change according to their age or depend on whether either of them is in a close relationship.

Only in one case did the differentiating effect of a demographic variable prove to be statistically significant—namely, in the case of the patient's sex and its impact on the development of the patient–therapist bond. It turns out that men build stronger alliances than women in this respect.

The results of difference tests lead to the conclusion that demographic variables do not determine the quality of the therapeutic alliance. Hypothesis H2 was therefore rejected, although the differentiating effect of sex should be noted.

DiscussionThe results of this empirical study allowed for exploring the quality of the therapeutic alliance in terms of whether it depended on several formal variables related to the psychotherapeutic process. Earlier results of empirical studies and the conclusions formulated on their basis made it reasonable to investigate to what extent the formal aspects of the psychotherapeutic process influenced the alliance and whether the quality of this alliance was differentiated by demographic variables. In the present study, working alliance in psychotherapy was thoroughly explored based on combined patient and therapist evaluations of its quality and with separate evaluations included in some analyzes as well. The collected empirical data and the strategy adopted to test the hypotheses yielded interesting results, partly supporting the earlier findings.

Of the formal aspects of psychotherapy, all four variables: work experience, the number of sessions held, the frequency of sessions, and the length of sessions, contributed to the quality of the therapeutic alliance to a small degree.

The factors conducive to a proper therapeutic relationship include the psychotherapist's work experience and the frequency of psychotherapeutic sessions; the length of sessions is such a factor to a slight degree only. Alliance quality increases if the psychotherapist is more experienced and if the patient attends the sessions regularly and frequently. Alliance quality improves also when sessions are longer. I controlled for sessions ranging in duration between 30 and 90 min; the largest number of observations (approximately 77%) concerned psychotherapeutic processes in which sessions lasted about an hour.

The study yielded an interesting result regarding the effect of the length of the psychotherapeutic process, operationalized as the number of sessions held, revealing that the alliance tended to deteriorate with time. This result confirms one of the patterns described by Kramer and colleagues,30 who found that even though the alliance is often strong when newly established, it may weaken during subsequent meetings. This may stem from the fact that the psychotherapist's engagement, harmonization (particularly emotional) with the patient, and activities aimed at hearing the patient out and at the containment of the patient's experience (present and frequent during the first sessions) partly give way to a focus on identifying the areas in the patient's life that require effort, work, and change on his or her part and that demand new, more adaptive forms of behavior and work on defense mechanisms. Such challenges may increase discomfort and a feeling of being unable to work further. They may also increase distance and negative emotions towards the psychotherapist, thus leading to a deterioration in alliance quality.

The alliance was also evaluated by the psychotherapist, and a similar pattern was found in this case as well—a deterioration in alliance quality as the number of psychotherapy sessions increased. There are several conjectures worth considering in this regard. The patient's reaction of discomfort and resistance to the expectations (appearing in the advanced stages of treatment) that he or she should put in more effort and make changes may have an impact on the psychotherapist's self-esteem and critical assessment of the alliance. After all, the evaluation of the working alliance as theorized by Bordin concerns the achievement of goals through the performance of tasks,4 and these dimensions become crucial in the advanced stages of psychotherapy. Psychotherapists’ low evaluation of the alliance in longer psychotherapy processes may stem from their awareness of the responsibility involved. It is possible that, with the growing duration of psychotherapy, psychotherapists become more attentive to what happens during sessions, to how the provisions of the contract are implemented, and to whether the patient does the tasks assigned to accomplish the goals that have been set. Psychotherapists’ increasing vigilance, especially when the goals are not achieved despite the passing of time, may manifest itself in a more neutral, restrained, and sometimes negative evaluation of the alliance.40 Both in psychotherapists and in patients, low evaluations of the alliance may also be related to the phenomenon of fluctuation—an increase in the strength of the alliance on some occasions and a decrease in its strength on others. Fluctuation occurs particularly in long processes and in the case of intensively working dyads. This phenomenon is inevitable, and, to a certain extent, it is a consequence of the intervention strategies activated by the therapist.28 It may also stem from the general non-coincidence of psychotherapists’ and patients’ evaluations of the alliance and the systematic underrating of this relationship by the former.41 What may suggest this last pattern is the negative value—the highest of all in the analyzes—of the standard path coefficient between the number of sessions held and the psychotherapist's evaluation of the alliance. The psychotherapist's low evaluation of the alliance may also reflect the actual state of this relationship. The alliance does not always develop linearly. Moreover, it may be impossible to pinpoint just one variable influencing the result of the analyzes because multiple factors mold the psychotherapeutic relationship.42 The pattern that has been detected requires further research, as there is considerable empirical material indicating that the alliance should grow stronger with time because the relationship in the dyad should deepen.5,25,28,29

The results of the study do not allow for identifying the demographic markers of the quality of psychotherapeutic alliance. Neither sex, age, or education, nor the patient's being single or in a relationship determines the quality of the alliance. It therefore seems that the expectation of alliance in psychotherapy is common; alliance is expected to an equal degree by individuals of different ages and with different levels of education, regardless of the presence or absence of close interpersonal relationships in their lives.

What is interesting is the fact that the analysis revealed no differentiating effect of the patient's marital status (relationship status). To my knowledge, this variable has not been investigated to date in studies on the quality of therapeutic alliance. It was assumed that patients who were single and not in a close romantic relationship might transfer this unfulfilled need to the relationship with the psychotherapist and build a stronger alliance. This, however, was not the case, perhaps because the working alliance, especially as conceptualized in Bordin's model,33,34 is largely formal and centered on the main goal, which is to enhance the patient's well-being, eliminate symptoms, and achieve recovery.

The only exception is the development of a bond in the psychotherapeutic process. Men need a slightly stronger therapeutic alliance than women. This can be understood as follows: if the alliance in psychotherapy is also partly a formal agreement concerning specific actions that should be performed to achieve specific treatment outcomes, and if other studies show that men generally build stronger interpersonal relations when these relations are based on a clearly defined goal and activities leading to the achievement of that goal,43–45 then perhaps they approach the alliance similarly, and hence their need for a stronger emotional bond with the psychotherapist during treatment.

ConclusionThe formal aspects of the psychotherapeutic process influence the alliance. Alliance develops to an equal degree in people of different ages and with different levels of education, regardless of the presence or absence of close interpersonal relationships in their lives.

LimitationsResearch on the issues raised in this article requires continuation and, importantly, replication. The adopted strategy of collecting and analyzing data and identifying the factors influencing the quality of working alliance carries certain limitations. Further research should address and eliminate them.

Future studies require increasing the sample size; both the group of patients and the group of psychotherapists must be larger to ensure stronger empirical support for SEM analyzes. Larger samples will also allow for ensuring that participants with various levels of extraneous variables are adequately represented.

As mentioned in the first part of the article, previous analyzes concerning the impact of variables on the quality of alliance usually included factors from the categories of personality and motivation. The present study did not include them. Perhaps some of the variables analyzed in this study are moderators between alliance quality and personality or motivational factors. A critical issue, though an exceedingly difficult one in the context of research into a phenomenon as delicate as the psychotherapeutic process, is the preparation of measurement and the collection of data for longitudinal analyzes. The present study was conducted on a cross-sectional basis, with only one measurement to rely on. Data collected from more than one measurement in the same dyad at different stages of alliance consolidation could show the dynamics of alliance depending on significant factors.