The level of lymph node involvement is the most important factor in staging colorectal cancer without metastasis. Sentinel lymph node mapping identifies the node(s) that most accurately reflect the lymph node status of patients, and intensive techniques that improve staging can be focused on these nodes. The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of ex vivo sentinel lymph node mapping in the staging of colon cancer.

Materials and methodsA prospective study was conducted on 125 patients from the Álava-Txagorritxu University Hospital Health Region (Álava), who were diagnosed prior to surgery with colon cancer without distant metastasis from September 2009 to December 2011. Ex vivo sentinel lymph node mapping with methylene blue was use in these patients to study the sentinel nodes with multiple slices using immunohistochemical techniques and haematoxylin–eosin staining. A comparative study was also performed based on a control group of 170 patients staged with conventional techniques, and involving a single slice and haematoxylin–eosin staining.

ResultsThe sentinel lymph node identification rate was 98%, with 5.6% false negatives. Upstaging occurred in 14.2% of cases compared to the group studied using conventional techniques (P=.006).

ConclusionsEx vivo sentinel lymph node mapping with methylene blue accurately reflects the lymph node status of patients with colon cancer. This approach upstages patients classified as stages i and ii by conventional techniques to stage iii, indicating chemotherapy that may improve their prognosis.

El estudio de los ganglios linfáticos supone el factor pronóstico más importante en el cáncer colorrectal sin metástasis. La técnica del ganglio centinela identifica el ganglio que mejor predice el estado ganglionar de un paciente y permite realizar en él técnicas de estudio intensivo que mejoran la estadificación. El objetivo del trabajo es estudiar la eficacia de la técnica del ganglio centinela en la estadificación del cáncer de colon.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo con 125 pacientes diagnosticados preoperatoriamente de cáncer de colon sin metástasis a distancia desde septiembre de 2009 hasta diciembre de 2011 en el Hospital Universitario de Álava-Txagorritxu en Álava. Realizamos la técnica del ganglio centinela ex vivo y con azul de metileno. El ganglio centinela se estudió realizando secciones múltiples y técnicas de inmunohistoquímica, además de hematoxilina-eosina. Realizamos un estudio comparativo con un grupo control con 170 pacientes estudiado de forma convencional mediante sección única y tinción de hematoxilina-eosina.

ResultadosIdentificamos el ganglio centinela en el 98% de los casos, con una tasa de falsos negativos del 5,6%. La supraestadificación lograda en el grupo con estudio del ganglio centinela se encuentra en el 14,2% con respecto al grupo estudiado convencionalmente (p = 0,006).

ConclusionesEl estudio del ganglio centinela realizado ex vivo y con azul de metileno predice el estado ganglionar de los pacientes con cáncer de colon. Esta técnica supraestadifica, pasando al estadio iii a pacientes que el estudio convencional determinaba como estadios i y ii, permitiendo que accedan a un tratamiento quimioterápico que podría mejorar su pronóstico.

Tumour staging with an accurate evaluation of lymph node metastases is the most important prognostic factor in colorectal cancer (CRC). Patients have different survival rates based on TNM staging. Thus, the early stages (I and II) have survival rates between 82% and 93%, while survival decreases to 59% at 5 years in the presence of lymph node metastases (stage III).1

Fifty per cent of patients with CRC are diagnosed in the early stages without lymph node metastases and are being treated with potentially curative surgery. However, 20%–30% will die of their disease within 5 years.2 This high percentage can be explained in part by the understaging of these patients due to an insufficient lymph node yield. We should note that chemotherapy in patients with lymph node infiltration has improved the survival, decreasing mortality by more than 30%.3

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) recommends studying at least 12 lymph nodes for correct staging.2 Intensive study techniques to determine lymph node involvement are being advanced to improve the staging of CRC patients. However, the large number of resources needed to implement such studies in all lymph nodes makes them unfeasible.

The sentinel lymph node (SLN) concept is based on the way tumour cells spread via the lymphatic drainage from the primary tumour site to the first lymph node. Thus, the SLN is at greatest risk for metastasis and identifying it can better predict the nodal status of the patient. SLN identification allows the use of intensive study techniques more efficiently. The main aim of this study is to determine the efficacy of the ex vivo SLN dye technique in colon cancer (CC) staging.

Materials and MethodsThis is a cross-sectional, crossover, single-centre study to determine the efficacy of SLN study in the staging of CC. One hundred twenty five patients from the Txagorritxu-Álava University Hospital were included in the study. A prospective cohort was selected between September 2009 and December 2011; it included all cases without randomisation. Diagnosis was made using colonoscopy, abdominal and pelvic CT scans and chest radiography. The SLN technique was performed by 5 surgeons with previous experience with using the technique for CC (up to 10 cases per surgeon). Patient inclusion criteria were as follows: CC, elective surgery, curative surgery, and being over 18 years of age. The exclusion criteria included Stage IVcancer, urgent and palliative surgery, and rectal cancer.

Additionally, a comparative study with a control sample was conducted in which only a conventional pathologic examination was performed (single haematoxylin–eosin section). This group comprised 170 patients consecutively operated on between June 2006 and February 2009. All of the patients were operated on by the same surgeons and met the same inclusion criteria as those in the SLN study. The pathology examination was not performed by the same pathologists who studied specimens in the SLN technique group. The information required for this group of patients was obtained via medical records review.

The primary endpoint was a staging change resulting from the SLN study. Other variables were the age and sex of the patient, the location and T and N tumour classification, the total number of lymph nodes and number of SLNs, the number of infiltrated lymph nodes according to the conventional study and the SLN study, and the type of involvement.

The procedures comply with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964, as amended in 2008 in Seoul. This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Txagorritxu-Álava University Hospital.

Sentinel Lymph Node IdentificationSLN identification was performed ex vivo after resection of the surgical specimen. We infiltrated 1–2mL of methylene blue peritumourally and into the subserosa, depending on the tumour size. We performed a massage for 5–10min to spread the dye through the lymph channels and dye the lymph nodes. Mesocolon dissection started near the tumour, following the dye-stained paths. We considered the SLNs to be the first 1–4 dyed lymph nodes and those through which a dyed lymphatic duct directly and clearly reaches the lymph node without becoming dyed itself.4

Intensive Study of the Sentinel Lymph NodeTwo-mm thick sections were prepared, and a single section was prepared for lymph nodes under 5mm. After fixation in 4% buffered formalin for 24h, six 4-μm sections were prepared. Haematoxylin–eosin and immunohistochemistry (cytokeratin monoclonal antibody CAM 5.2) staining techniques were sequentially applied, so that three sections were studied with each technique.

Interpretation of the Anatomopathological FindingsAccording to the AJCC5 classification, we considered metastasis an involvement greater than 2mm, micro-metastases involvements from 2mm to 0.2mm, and tumour groups of colonies and isolated cells those equal or less than 0.2mm. The presence of metastases and micro-metastases modified staging, as pN1 and pN1mi was considered, respectively. Lesions 0.2mm or smaller did not change staging and were considered pN0 (i+). The remaining nodes were conventionally studied using single section and haematoxylin–eosin staining.

Statistical AnalysisQuantitative variables were described by means and standard deviations, and categorical variables were described as frequencies and percentages. The similarity of the samples was checked using Student's t-test and the chi-squared test. The latter test was also used to compare the proportion of infiltrated lymph nodes and overstaging. The validity of the diagnostic test was analysed to obtain sensitivity and specificity and confidence intervals and compare them to those of the gold standard (conventional lymph node study). Statistical significance was set at P>.05.

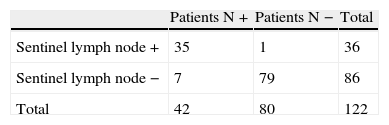

ResultsGroup Studied Using the Sentinel Lymph Node TechniqueSLN identification was accomplished in 122 (97.6%) of the 125 patients, and technique failure was determined in 2.4% of the cases. The SLN study detected infiltration in 36 (29.5%) of the 122 patients (Table 1). SLN predicted total lymph node status in 115 of the 122 cases, so that test accuracy was 93.4% (95% CI: 89.1%–97.8%), sensitivity was 83.3% (95% CI: 72.1%–94.6%), and specificity was 98.8% (95% CI: 96.3%–100%).

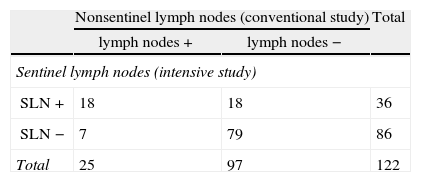

The SLN study detected lymph node metastases in 18 of the 25 patients who showed metastases in the conventional study (lymph node +) (Table 2). Thus, 7 of 122 patients had no SLN metastases and had at least one other affected lymph node. Therefore, the false negative rate was 5.7%.

Group Studied Using the Sentinel Lymph Node Technique. Distribution of Patients by Lymph Node Anatomopathological Results According to Technique: Conventional Study vs Intensive Study (SLN Technique).

| Nonsentinel lymph nodes (conventional study) | Total | ||

| lymph nodes + | lymph nodes − | ||

| Sentinel lymph nodes (intensive study) | |||

| SLN + | 18 | 18 | 36 |

| SLN − | 7 | 79 | 86 |

| Total | 25 | 97 | 122 |

The SLN study detected lymph node metastases in 18 (18.6%) of the 97 patients who showed no metastases in the conventional study (lymph node −; Table 2). The intensive study of the sentinel lymph node in 18 patients detected metastases in 12, micro-metastases in 5 and isolated tumour cells (ITC) in one patient. Thus, an upstaging in this group was 18.6% using the SLN technique.

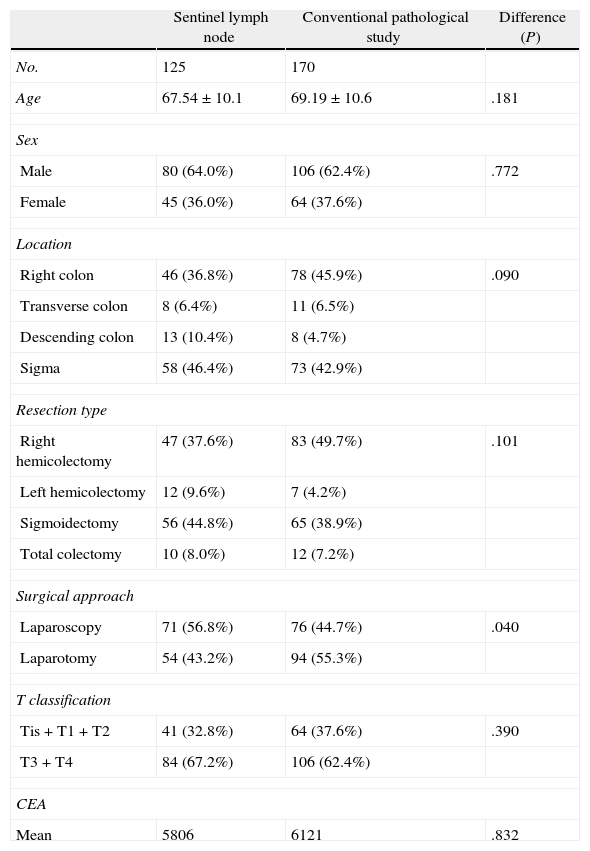

Comparison between the sentinel lymph node technique group and the conventional study group.

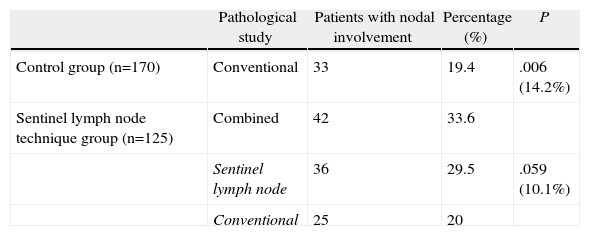

Table 3 shows the homogeneity of the two groups compared, where the surgical approach is the only difference between the two samples. In the control group (conventionally studied), we detected lymph node metastases in 33 (19.4%) of 170 patients (Table 4), while in the SLN study group, we detected lymph node infiltration in 42 (33.6%) of 125 patients. That is, the SLN study found 14.2% more patients with lymph node infiltration, a difference that was statistically significant. Therefore, the upstaging achieved by the SLN technique was 14.2%. Table 4 shows that in the group studied with the SLN technique, the SLN study alone detected lymph node involvement in 36 (29.5%) of the 125 patients. This represents 10% more patients with lymph node infiltration compared to the control group (19.4%). In contrast, the conventional study detected an almost identical percentage of patients with lymph node metastases in the 2 groups (19.4% and 20%, respectively).

Patient Features of the Sentinel Lymph Node Study Group and the Control Group.

| Sentinel lymph node | Conventional pathological study | Difference (P) | |

| No. | 125 | 170 | |

| Age | 67.54±10.1 | 69.19±10.6 | .181 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 80 (64.0%) | 106 (62.4%) | .772 |

| Female | 45 (36.0%) | 64 (37.6%) | |

| Location | |||

| Right colon | 46 (36.8%) | 78 (45.9%) | .090 |

| Transverse colon | 8 (6.4%) | 11 (6.5%) | |

| Descending colon | 13 (10.4%) | 8 (4.7%) | |

| Sigma | 58 (46.4%) | 73 (42.9%) | |

| Resection type | |||

| Right hemicolectomy | 47 (37.6%) | 83 (49.7%) | .101 |

| Left hemicolectomy | 12 (9.6%) | 7 (4.2%) | |

| Sigmoidectomy | 56 (44.8%) | 65 (38.9%) | |

| Total colectomy | 10 (8.0%) | 12 (7.2%) | |

| Surgical approach | |||

| Laparoscopy | 71 (56.8%) | 76 (44.7%) | .040 |

| Laparotomy | 54 (43.2%) | 94 (55.3%) | |

| T classification | |||

| Tis+T1+T2 | 41 (32.8%) | 64 (37.6%) | .390 |

| T3+T4 | 84 (67.2%) | 106 (62.4%) | |

| CEA | |||

| Mean | 5806 | 6121 | .832 |

Comparison of Patients With Lymph Node Infiltration According to the Pathological Examination Type Performed (Control Group/SLN Technique Group).

| Pathological study | Patients with nodal involvement | Percentage (%) | P | |

| Control group (n=170) | Conventional | 33 | 19.4 | .006 (14.2%) |

| Sentinel lymph node technique group (n=125) | Combined | 42 | 33.6 | |

| Sentinel lymph node | 36 | 29.5 | .059 (10.1%) | |

| Conventional | 25 | 20 |

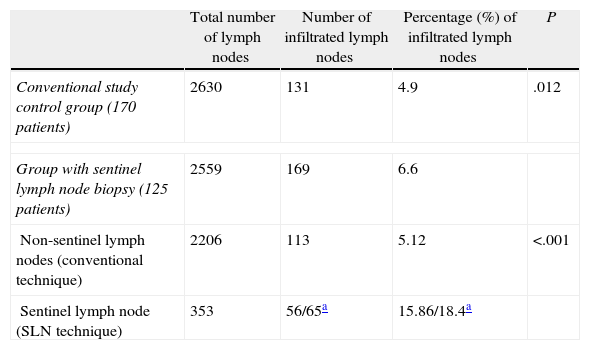

A mean of 20.5 lymph nodes (range: 3–58) were extracted in the SLN study group, while the mean was 15.5 nodes in the control group (range: 0–62), a difference that was statistically significant (P<.001). Table 5 shows that in the SLN study group, lymph node infiltration was detected in 169 (6.6%) of 2559 nodes examined, while in the control group, we detected metastases in 131 (4.9%) of the 2630 nodes found. Thus, a higher percentage of infiltrated lymph nodes were detected in the SLN study group than in the conventional study used for the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (P=.012). The conventional study detected a similar percentage of infiltrated lymph nodes for the 2 groups (4.9% and 5.1%).

Comparison of Lymph Node Metastatic Infiltration According to the Pathological Examination Type Used (Control Group/SLN Technique Group).

| Total number of lymph nodes | Number of infiltrated lymph nodes | Percentage (%) of infiltrated lymph nodes | P | |

| Conventional study control group (170 patients) | 2630 | 131 | 4.9 | .012 |

| Group with sentinel lymph node biopsy (125 patients) | 2559 | 169 | 6.6 | |

| Non-sentinel lymph nodes (conventional technique) | 2206 | 113 | 5.12 | <.001 |

| Sentinel lymph node (SLN technique) | 353 | 56/65a | 15.86/18.4a | |

In addition, Table 5 shows the difference in lymph node involvement in the SLN study group. The study of 353 SLNs detected more lymph node involvement than the conventional study of 2206 non-sentinel lymph nodes, a difference that was statistically significant (P<.001).

DiscussionLymph node involvement is the single most important prognostic factor in CRC. Studies6–9 show that survival increased when the number of studied lymph nodes increased, especially when those lymph nodes were negative. Proper staging of CRC includes identifying at least 12 lymph nodes; a smaller number may assume understaging and lead to a poorer prognosis, as the patient will not benefit from adjuvant therapy.

The number of lymph nodes detected in the surgical specimen depends on multiple factors, including pathologic study limitations. The intrinsic difficulty of the technique is added to the fact that 70% of infiltrated lymph nodes are smaller than 5mm and are likely not to be detected.10 Furthermore, the study by single section allows the analysis of only 1% of lymph node tissue, so that small tumour lesions with a subcapsular location can remain undetected.11

The SLN technique identifies a lymph node that can reliably predict the patient's nodal status, allowing them to be studied using intensive techniques without significant resource consumption. Numerous studies4,11–14 offer overstaging results of 10%–20% with the use of immunohistochemical and molecular biology (reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR]) techniques. Performing multiple sections improves staging up to 9%.15

The use of radioisotopes is standard in breast cancer and melanoma. However, the use of a dye has been reported as a good alternative.16 From our point of view, the dye technique is simpler because it does not require collaboration with other services, such as nuclear medicine and gastroenterology. Furthermore, we avoid the risks of a colonoscopy, which is necessary to infiltrate the radiotracer. Therefore, and given the absence of studies confirming that the use of radiotracers achieves better results, we believe that the use of dyes such as methylene blue is the best SLN study technique in CRC.

Aberrant lymphatic drainage and improved lymphatic circulation when the surgical specimen has not yet been resected are arguments in favour of the in vivo technique. The first assumes the existence of nodal metastases outside the boundaries of standard resection. However, the frequency of such metastases is low, ranging between 2% and 8%, and quite a few groups cannot even detect it.17,18 Regarding lymphatic drainage in the excised surgical specimen, experience with breast cancer and melanoma confirms that massaging the infiltrated area allows proper dye spread via the lymphatic circulation.19 In addition, surgical resection disrupts the neurological mechanism that regulates the constriction of the lymphatic channels, thus facilitating lymphatic circulation.20

In 2001, Wong et al.21 published the first large series of patients studied ex vivo using the SLN technique. The results obtained in this study and in others published later are similar to those achieved when using the in vivo technique.20–23 As arguments for the ex vivo technique, we could say that it prevents the risk of perforation and the spread of tumour cells caused by tumour manipulation and prevents anaphylactic reaction to contrast, without modifying the surgical procedure, and it allows the procedure to be performed by a surgeon who is not directly involved in the specific intervention, thus requiring a shorter learning curve. Moreover, from our perspective, the technique's main advantage is its simplicity, which is especially important for large tumours or those localised in the rectum and for laparoscopic surgery. Thus, groups that commonly use the in vivo technique can use the ex vivo procedure in the above-mentioned cases.24,25

The SLN identification rate varies between 58% and 100% with most authors20–27 reporting values above 95%, while the false negative rate is between 0% and 10%. These results depend mainly on the experience of the team performing the procedure and the amount of infiltrated dye.13 The type of technique, either in vivo or ex vivo and using either a radiotracer or dye, does not seem to influence these results.20,28 In breast cancer, validation parameters recommend at least a 95% SLN identification rate and a 5% or lower false negative rate.29 The learning curve for the SLN technique in CRC is unknown, but it appears to be lower than in breast cancer, which requires 5–10 cases per surgeon.30,31 Our study was conducted by surgeons with previous experience of 10 cases, and we achieved SLN identification in 98% of cases and a false negative rate of almost 5%.

Upstaging in our study was 14% compared with the conventionally studied control group. This value is comparable to those reported by groups with more experience.11–14,27 The conventional pathological study detected a similar percentage of infiltrated lymph nodes in the 2 groups (4.9% and 5.1%). Therefore, the upstaging achieved in the SLN study group can be attributed to the SLN technique. We emphasise that the SLN study's aim is not to change surgery and avoid lymphadenectomy. Thus, we managed to recover the cases responsible for the false negative rate of the conventional study. The combined pathological study benefits from the upstaging of the SLN study, while the conventional study addresses false negatives.

We want to remark that the conventional study of the 2 groups detected a similar percentage of infiltrated nodes, so that the greatest total number of infiltrated lymph nodes detected in the SLN group can be attributed to the SLN technique (Table 5).

We end by stating that the predictive value of lymph node micro-metastases in CC survival is unclear, and studies with longer follow-ups of these patients are needed.32,33

We conclude that the SLN technique with methylene blue performed ex vivo predicts nodal status in patients with CC. The SLN technique achieves upstaging and classifies as stage III, patients who conventional study would have classified as Stage 0, I and II. This increase in staging allows these patients access to a chemotherapy treatment that could improve their prognosis.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Sardón Ramos JD, Errasti Alustiza J, Campo Cimarras E, Cermeño Toral B, Romeo Ramírez JA, Sáenz de Ugarte Sobrón J, et al. Técnica del ganglio centinela en el cáncer de colon. Experiencia en 125 casos. Cir Esp. 2013;91:366–371.