Tuberculosis (TB) of the hepatobiliary system is uncommon and it is a rare cause of bile duct stenosis. The symptoms are nonspecific, the most important of which is jaundice. Hepatobiliary TB is difficult to differentiate from other entities such as cholangiocarcinoma, and many cases require surgery, histology and bacteriological confirmation to reach a definitive diagnosis. Treatment does not differ from pulmonary TB and involves the administration of quadruple therapy for one year. In order to resolve the bile duct obstruction, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is used to insert a bile stent; meanwhile, some cases may require surgical decompression.

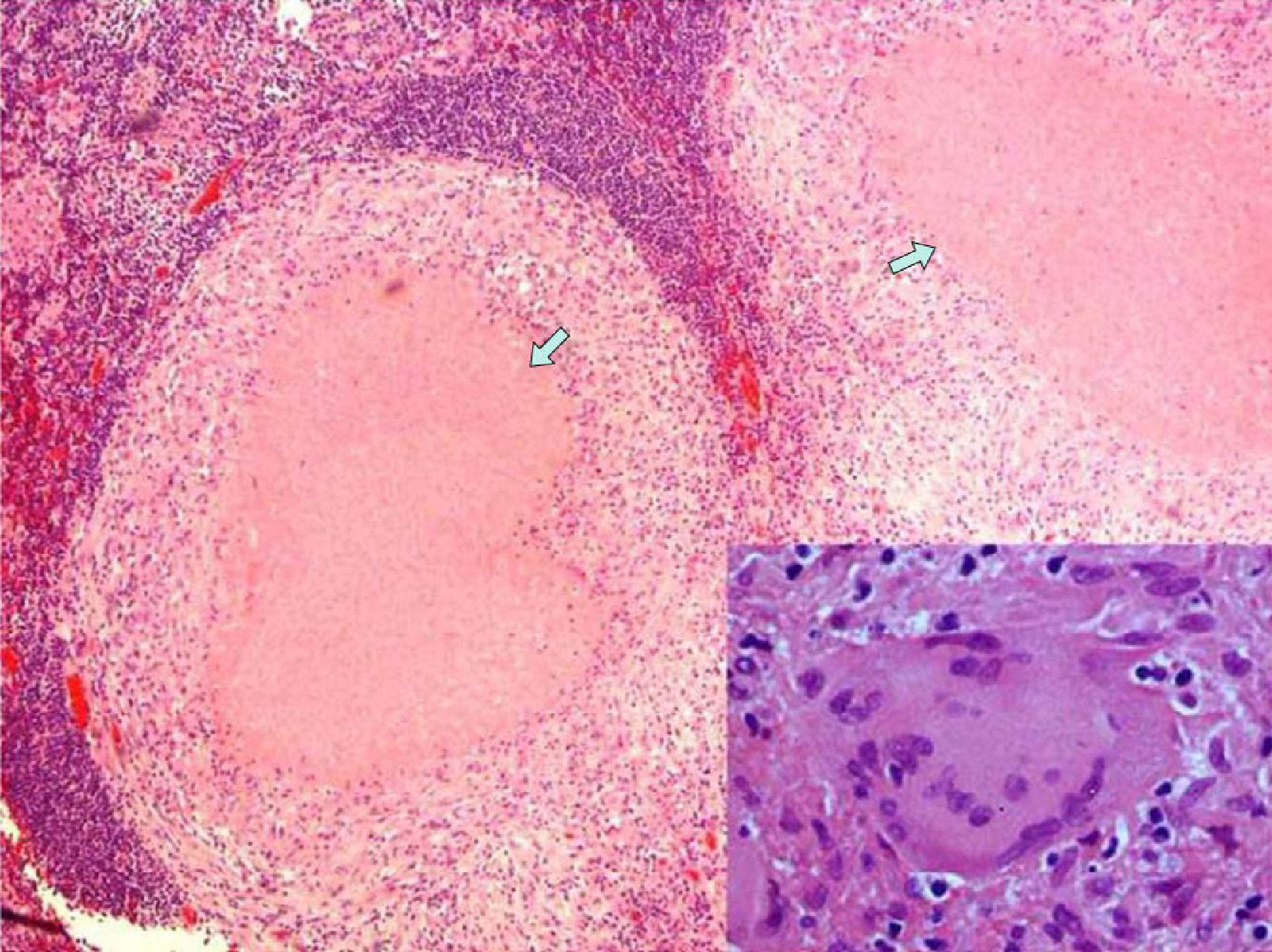

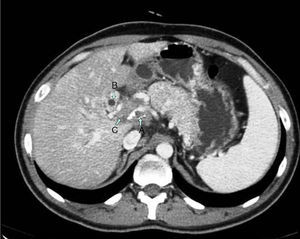

We present the case of a 29-year-old male patient with no prior medical history of interest that came to our Emergency Department due to abdominal pain that had been developing over the previous 3 weeks. The pain was poorly defined, located in the right hypochondrium, and accompanied by jaundice of the skin and mucous membranes with choluria but no other alterations. On admittance, the work-up showed a pattern of extrahepatic cholestasis with bilirubin 4.2mg/dl and GGT 467IU/l. Basic biochemistry, complete blood count and coagulation were within normal limits. Tumor marker levels were also normal. Chest and abdominal radiographies presented no alterations. Abdominal ultrasound revealed the presence of a normal-sized gallbladder with biliary sludge, no signs of inflammation and moderate dilatation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile duct, observing multiple lymphadenopathies in the area as well as under the spleno-portal axis. The pancreas had a normal appearance with no observed free fluid. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 1) confirmed the dilatation of the bile duct seen on ultrasound, showing narrowing of the common bile duct at the hepatic hilum. We identified a heterogeneous mass of 30×40mm with ill-defined edges and internal calcifications responsible for the dilatation of the bile duct as well as the cavernous transformation of the portal vein. In addition, intercaval-aortic and gastrohepatic lymphadenopathies larger than 1cm were detected. We attempted to use endoscopic ultrasound needle aspiration to biopsy the mass, but this was not possible because of the location and collateral circulation. Using ERCP, we inserted a plastic stent (8.5F×10cm) in the common bile duct after the bile duct cytology was negative for malignancy. Since the diagnostic tests did not confirm whether the process was benign or malignant, exploratory laparotomy was indicated. We observed local inflammation of the gallbladder and hepatic pedicle with compression of the middle common bile duct caused by a cluster of at least 3 lymphadenopathies. Intraoperative biopsy of one of these lymph nodes confirmed the existence of a granulomatous inflammatory process with necrosis. Cholecystectomy and lymph node enucleation were performed with decompression of the main bile duct. Pathology (Fig. 2) revealed the existence of tuberculoid necrotizing granulomatous lesions and the culture was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. With the diagnosis of tuberculosis of the hepatic hilum, standard TB treatment was administered for 9 months (isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide the first 2 months, and isoniazid and rifampicin the remaining 6 months) with good clinical and radiological response.

Obstructive jaundice due to tuberculosis is a rare entity. Mechanical obstruction of the bile duct may be caused by pancreatitis, lymphadenitis with or without fistulization to the distal bile duct, retroperitoneal mass compressing the bile duct, or endoluminal lesions simulating cholangiocarcinoma, all of tuberculous origin.1

Reaching a definitive diagnosis of hepatobiliary TB without resorting to surgical exploration is very difficult.2 In our case, it was necessary to perform exploratory laparotomy since we could not rule out malignancy with all the diagnostic tests available. Abdominal CT is the imaging test with the highest diagnostic sensitivity and specificity.3 Magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRCP) is useful for visualization of the biliary tree and localization of the point of obstruction.4 ERCP allows for exploration and sampling for cytology and bacteriology; however, confirmation is very rare, so this test is mainly useful for the decompression of the bile duct with endoprosthesis.5 Fine needle aspiration may be useful for preoperative diagnosis because it allows for samples to be taken for bacteriology and cultures, but it has the disadvantage of disseminating potentially malignant or tuberculosis cells.6

In most published cases, surgical intervention was necessary, which was able to resolve the obstruction as well as to make the definitive diagnosis by means of histological and bacteriological confirmation.7 With an accurate diagnosis, there are reports of resolution of the symptoms with tuberculosis therapy alone.8 In our patient, evidence of granulomas and necrosis in the intraoperative histology of the lymph nodes confirmed the benign diagnosis, avoiding resection or bypass surgery, since simple enucleation of the lymphadenopathies was sufficient to resolve the cholestasis.

Please cite this article as: Fernández Muinelo A, Salgado Vázquez M, Núñez Fernández S, Pardo Rojas P, Gómez Lorenzo FJ. Ictericia obstructiva secundaria a tuberculosis ganglionar del hilio hepático. Cir Esp. 2013;91:611–612.