Omental torsion is an infrequent cause of acute abdomen and its symptoms are non-specific, often presenting with pain at the right iliac fossa as the only symptom. Its aetiology remains unknown, but different risk factors have been associated with the disease, including obesity, congenital malformations, and tumours. These risk factors have been classified as predisposing or triggering, primary or secondary, and external or internal.

Clinical caseThis is a case of a 24-year-old male who complained about pain in the right iliac fossa without any other symptoms. The diagnosis was acute appendicitis, but during the laparoscopic approach, omental torsion was found.

ConclusionThe diagnosis of omental torsion is complex. However, computed tomography and ultrasound have been used successfully. The treatment for omental torsion is the resection of necrotised tissue by a laparoscopic approach.

La torsión de epiplón es una causa infrecuente de abdomen agudo y sus síntomas no son específicos, frecuentemente presentándose como único síntoma dolor en fosa iliaca derecha. La etiología es desconocida, pero se han asociado diferentes factores de riesgo con esta patología, incluyendo obesidad, malformaciones congénitas y tumores. Estos factores de riesgo han sido clasificados como predisponentes o desencadenantes, primarios o secundarios y externos o internos.

Caso clínicoSe presenta el caso de un masculino de 24 años con dolor en fosa iliaca derecha sin otros síntomas acompañantes. Se diagnosticó como apendicitis aguda, encontrando durante la laparoscopía una torsión de epiplón.

ConclusiónEl diagnóstico de la torsión de epiplón es complejo. Sin embargo, la tomografía axial computarizada y el ultrasonido se han utilizado con éxito. El tratamiento consiste en la resección del tejido necrótico por un abordaje laparoscópico.

Omental torsion was first described by Eitel in 1899, and segmentary infarct of the greater omentum was described for the first time by Bush in 1896. After the description by Bush fewer than 250 cases have been reported, of which only 26 were treated using laparoscopic omentectomy.1–4 The probability of finding a case of omental torsion vs a case of acute appendicitis is 4:1000, and the incidence reported in the literature ranges from 0.0016% to 0.37%.5 Omental torsion generally presents in the fourth or fifth decade of life. There is a ratio of 5:1 in terms of predisposition in men and women, given that the latter are able to store more adipose tissue, while only 0.1% of reported cases are in children. The paediatric age at which it may present is thought to be from 9 to 16 years old, excluding children younger than 4 years old due to their small amount of adipose tissue.6–10

Omental torsion aetiology is unknown, and there are several hypotheses.11 Donhauser and Loke12 classified omental torsion as either primary or secondary. Secondary omental torsion is associated with cysts, omental tumour, hernias and adherences.11,12 Adams13 classified this pathology as having triggering factors or predisposing factors. Among the latter anatomical variations, obesity and the distribution of the circulation in the omentum stand out.13,14

A case of omental torsion is presented below, treated with partial laparoscopic omentectomy.

Clinical caseThe 24-year-old male patient weighed 78kg, was 1.73m tall and had a BMI of 26kg/m2. He visited the A&E department due to abdominal pain which had developed over 3 days, located in the right iliac fossa. It was of moderate intensity, without irradiating or exacerbation with any movement, and was not modified by anything. He referred no nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, fever or urinary symptoms. In the physical examination arterial pressure of 163/77mmHg was found, with a heart rate of 86 beats per minute, a respiratory frequency of 18 breaths per minute and a temperature of 37.1°C. He was in good general condition, with a distended abdomen, reduced peristalsis, slight pain on superficial and deep palpation in the right iliac fossa and no data respecting peritoneal irritation; Murphy's, McBurney's and Giordano's signs were all negative.

Laboratory test results showed slight leukocytosis of 11,600/μL, 15.2g/dl haemoglobin, 251,000/μL platelets, 90mg/dl glucose, 4.2g/dl albumin and 0.39UI/l total bilirubin. A general urine analysis showed no alterations. An ultrasound scan of the pelvis and appendix showed changes in the subcutaneous tissue of the lower right quadrant and liquid in the base of the cecum, while it was not possible to visualise the appendix.

The diagnosis was of acute appendicitis, and a laparoscopic approach was selected.

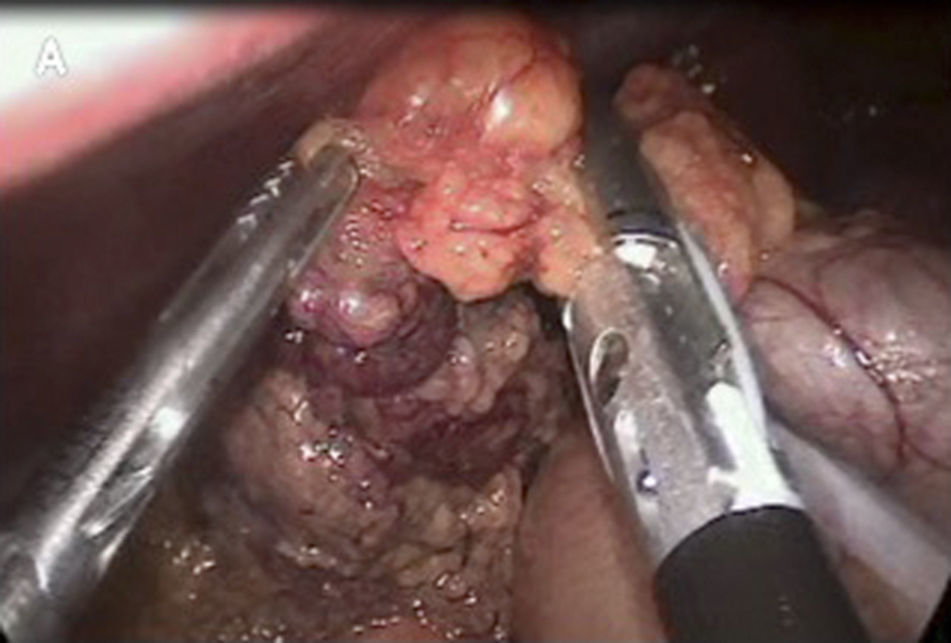

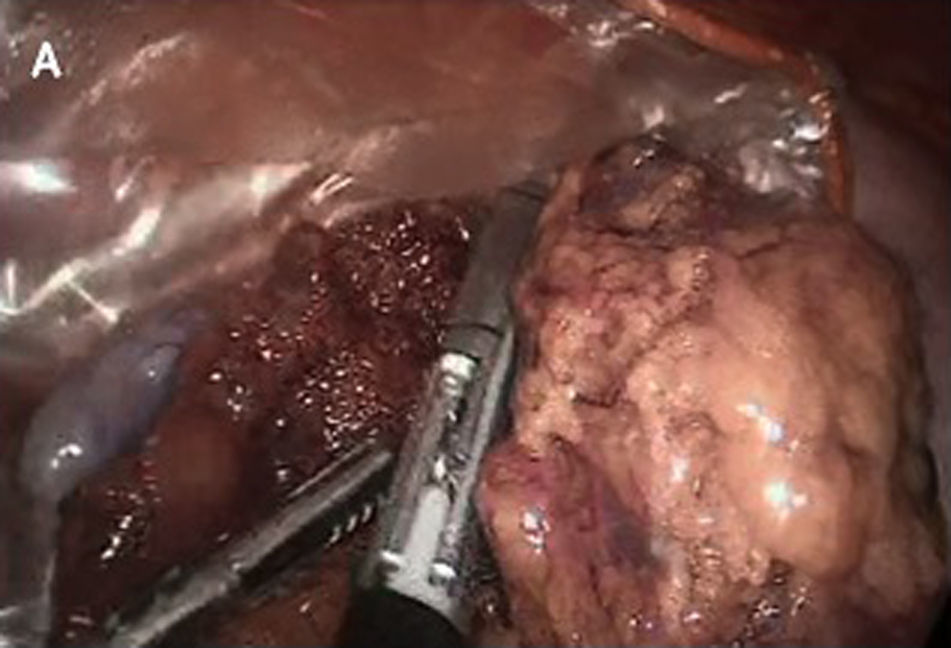

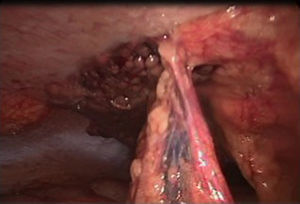

Omental torsion was detected during surgery, with signs of necrosis. It was therefore decided to perform a partial laparoscopic omentectomy and incidental appendectomy (Figs. 1–3). The patient presented fever of up to 38.5°C in the two days after surgery, and this fell after antipyretic treatment. It was decided to carry out a precautionary computerised axial tomography (CAT), and this showed an increase in the mesenteric fat of the right flank and right iliac fossa, cecal ganglia and free intra-abdominal gas bubbles associated with the recent surgery. There were no alterations in the rest of the abdomen.

The patient was discharged on the fifth day after the surgical operation, with an antibiotic and analgesics.

DiscussionOmental torsion develops with a set of turns around its own axis that compress the distal right epiploic artery. This causes right abdominal pain in up to 90% of cases.5 Omental torsion may occur in the lower left quadrant as well as in the right one. It predominates in the latter because it is longer, so that it is more likely to turn towards this side. As abdominal pain is more frequent on the right side, it may be confused with other pathologies such as acute cholecystitis, acute appendicitis, perforated duodenal ulcer or peritoneal pseudomyxoma. During the process of omental torsion it may cause venous obstruction, oedema or arterial compromise, leading to omental infarct.4,8,11,12

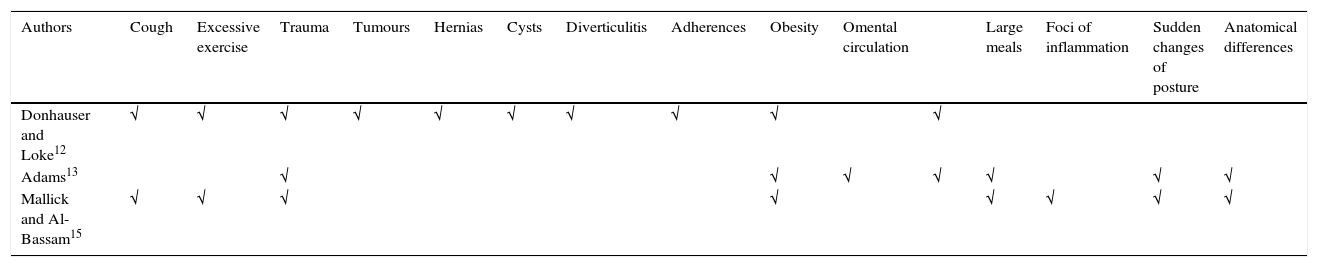

The aetiology of primary omental torsion is unknown; several factors have been associated with a predisposition to the disease. Some authors such as Donhauser and Loke,12 Adams,13 Mallick and Al-Bassam15 have proposed classifications which suggest that excess weight is a factor that predisposes to this pathology6 (Table 1). Analytical studies at 30, 20 and 10 years in Toronto, Canada and Melbourne, Australia, show major increases in the incidence of omental torsion of 0.215% and 0.166%, respectively, probably associated with the increase in obesity.16

Risk factors.

| Authors | Cough | Excessive exercise | Trauma | Tumours | Hernias | Cysts | Diverticulitis | Adherences | Obesity | Omental circulation | Large meals | Foci of inflammation | Sudden changes of posture | Anatomical differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donhauser and Loke12 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Adams13 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Mallick and Al-Bassam15 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Preoperative diagnosis is complex due to the ambiguity of the symptoms with which this condition presents. These include abdominal pain, pain in the right iliac fossa, hypersensitivity in the affected area, leukocytosis and a fever of less than 38°C.13,15–18 The abdomen is distended in more than 50% of cases, with hypersensitivity to touch, nausea, vomiting, leukocytosis and a rise in temperature that usually does not reach 38°C, unlike acute appendicitis.

Our patient was overweight, with a BMI of 26kg/m2, and this is a predisposing factor for omental torsion that we found cited in the literature. He presented with pain in the right iliac fossa and stated that he had suffered no nausea, vomiting or fever: nevertheless, these symptoms are often found in association with pain in patients with this condition. Apart from slight leukocytosis there were no relevant findings in the laboratory analysis. Many articles describe the same clinical presentation, with less intensity in children.5,19,20

In the majority of cases imaging studies show no specific radiological sign which indicates omental torsion. It may be confused with lipoma, liposarcoma, appendicitis, a twisted intestine, adipose tissue necrosis or paniculitis.17 Oğuzkurt et al.5 stated that a sterile serohaemorrhagic liquid is always present in the peritoneal cavity. Based on this, Mallick et al.15 reported a case in which ultrasound scan was used to diagnose this disease prior to surgery.5 Imaging studies are highly important for the diagnosis of this entity, and ultrasound currently detects a minimum amount of intra-abdominal fluid; ultrasound scan usually shows an ovoid mass adhering to the anterior abdominal wall. It is described as an incompressible hyperechoic lesion with hypoechoic edges, and it is associated with the hypersensitivity of the lesion.5,21

Magnetic resonance shows lineal hypointense structures corresponding to the low flow in the mesenteric vessels within a hyperintense mass of fat in T1. Congestion and oedema of the greater omentum are shown in adjusted T2.

The results of computerised axial tomography (CAT) show an ovoid mass adhering to the abdominal wall in the umbilical region or anterolateral in the middle of the colon. If the region is medial respecting the ascending colon this probably indicates omental torsion, while if is at the cecum-colon then it is associated with appendicitis.22,23 The typical characteristic of omental torsion in CAT is its diffuse pattern in the form of a fatty and fibrous whirl, although it is not specific enough to show whether it forms a part of an abdominal organ.16,24 It is also possible to observe two signs in CAT which suggest the presence of this disease. In the “sign of the vascular pedicle” there is a central amplifying point in the mesenteric vessel surrounded by multiple whirls of the smaller mesenteric branches. The “whirlpool sign” is described as a cloudy mass of fat with concentric lines of fat, with torsion of the blood vessels inside the greater omentum. These turn around a central vascular line,17 and this last sign makes it possible to confirm torsion of the greater omentum.

The treatment of omental torsion is divided into two main branches: conservative or surgical. In cases of secondary omental torsion the underlying condition is corrected, followed by radiological monitoring. Surgical treatment involves the resection of the damaged part of the omentum, while some authors state that this also prevents possible sepsis while achieving shorter hospitalisation.

ConclusionOmental torsion is a rare entity in cases of acute abdomen that may easily be confused with other pathologies due to its non-specific clinical presentation, making diagnosis complex.

The most recommended imaging study when there is the suspicion of this pathology is computerised tomography to show the “whirlpool sign”.

The treatment of choice is surgical resection of the affected segment, either by laparotomy or using a laparoscopic approach. The latter is less invasive and requires less recovery time.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Zaleta-Cruz JL, Rojas-Méndez J, Garza-Serna U, González-Ruvalcaba R, de Elguea-Lizarraga JO, Flores-Villalba E. Torsión de epiplón. Reporte de caso. Cir Cir. 2017;85:49–53.