Supracondylar humerus fractures are common in children between 5-7 years of age, and more frequent in the males. With 90-95% of these fractures produced by an extension mechanism, the urgency of immediate care is to prevent complications and sequelae.

ObjectiveTo establish the clinical and epidemiological profile of supracondylar humerus fractures, in a Regional General Hospital of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social in Yucatan Mexico, during 2011-2013.

Material and methodsA cross-sectional study was performed to calculate the association between the variables using odds ratios and statistical significance (p < 0.05) using the chi2 test.

ResultsA series of 56 cases were analysed. The mean age was 2.6 ± 5.33 years. The main cause of the injury was falling over at home. Male gender is associated with extension injury mechanism (OR 5.6, 95% CI; 1.0-30.1, p = 0.03). It was observed that the longer time elapsed between injury and medical treatment leads to more hospital days (r = 0.40; p = 0.002). Surgical treatment was established in 44 cases (78.6%); 18 (40.9%) with closed technique and 26 (59.1%) with open reduction. In all cases nails were used in cross configuration. Ten complications were reported.

ConclusionsSupracondylar humerus fractures are a common injury in children. Males are more likely to be injured by extension, and the speed in receiving medical treatment is an important issue.

Las fracturas supracondíleas de húmero son frecuentes en niños entre 5 y 7 años de edad; la prevalencia mundial oscila entre el 3 y el 16%, predominando en varones; el 90-95% corresponde a lesiones por extensión; la urgencia de una atención inmediata radica en la prevención de complicaciones y secuelas.

ObjetivoEstablecer el perfil clínico epidemiológico de las fracturas supracondíleas de húmero en niños atendidos en el Hospital General Regional N. 1 del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, en Yucatán, durante 2011-2013.

Material y métodosEstudio transversal analítico. La fuerza de asociación entre variables se midió mediante razones de momios (RM) sin valor estadístico significativo con la prueba de la chi al cuadrado, estableciéndose el valor de p < 0.05.

ResultadosSe analizaron 56 casos, con una media de edad ± desviación estándar de 2.6 ± 5.33 años; el mecanismo de lesión más frecuente fue la caída en el hogar. Se encontró asociación entre el género masculino y el mecanismo de lesión por extensión (RM 5.6; intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%, 1.0-30.1; p = 0.03) y que a mayor tiempo transcurrido entre lesión y atención médica, más días de estancia hospitalaria, (r = 0.40; p = 0.002). El tratamiento fue quirúrgico en 44 casos (78.6%), 18 (40.9%) con técnica cerrada y 26 (59.1%) con reducción abierta; en el 100% se usaron clavillos con configuración cruzada, se reportaron 10 complicaciones.

ConclusionesLa fractura supracondílea de húmero es frecuente en niños; los varones tienen mayor probabilidad de presentar lesiones por extensión; la rapidez de la atención médica es importante.

Supracondylar humerus fracture is a solution of continuity of the distal metaphysis of the humerus above the physeal line; it is the second most frequent type of fracture in children aged 5 to 71,2 and the most common in relation to elbow injuries (86%)3; it is the principal type of fracture requiring surgery in the paediatric age4, and it is predominant in males, with the left arm as the most affected one (67%)5,6. These injuries are classified as extension fractures, which represent 97 to 99% of cases, and flexion fractures, with represent 2.5%7; the urgency in treatment is that early anatomical reduction reduces complications8.

The most widely used classification, on a global scale, is Gartland's classification, which groups these lesions into 3 grades: I: anterior humeral cortex fractures with no displacement and minimal angulation; II: anterior humeral cortex fracture with major angulation and mild displacement, and III: displaced fracture with no cortical contact; this group may be posteromedial or posterolateral. Associated injuries are generally caused by close anatomical relations; for instance, oedema may cause vascular (0.5%) or nerve lesions7–9.

The purpose of the treatment is to provide stability and to prevent cubitus varus deformity; it is recommended that type I fractures with an angulation less than 20 be treated conservatively with immobilization for 3 weeks; if this angulation is more than 20, closed manipulation under anaesthesia is recommended. For type II fractures, reduction under anaesthesia with longitudinal traction is recommended. For type III, closed reduction with percutaneous pins is considered the gold standard, since it is a minimally invasive method, there is a lower risk of complications and sequels, which, in addition, favours a shorter hospital stay9,10 and, by conserving the biomechanical function of the elbow joint, rehabilitation is faster, with full recovery in an average of 8 weeks11. It has been observed that in 25% of percutaneous fixations, satisfactory aligning is not achieved, and remanipulation becomes necessary, increasing the risk of varus and valgus deformities in the long term, presented in up to 60% of the cases of remanipulated patients. Open fixation, which has a lower incidence of displacement12, is indicated as the first instance for exposed fractures when neurovascular lesion is suspected, and where closed reduction is not enough, or 2 or more attempts of percutaneous fixation with pins were required11. Some authors, such as Pretell et al.6, indicate performing open reduction on Gartland III-type fractures with significant angulation; they observed good to excellent results in up to 95% of the cases when comparing open reduction to closed reduction only in fractures with severe displacement; however, most authors indicate to begin with closed reduction and after 2 attempts, to consider open reduction, since repetitive manipulation may cause rigidity and neuropraxia13. Other authors state that surgical fixation is indicated in most type II and III fractures to prevent defective consolidation; they state that better results can be obtained than with closed reduction and placing a cast14. There is no difference between both reduction methods in terms of the presence of rigidity, although some studies have reported more rigidity in patients treated with open reduction15. In addition, no differences have been found between both methods in motor or carrying angle ranges. Closed reduction has better functional results13.

In Mexico, closed reduction and percutaneous fixation with pins is the preferred treatment; however, Olalde et al.7 reported 97% good results for open reduction. Delgado et al.2 reported an incidence of 3 to 16% of all fractures, with the most common injuries in the elbow, about 60% of total fractures, with 90-95% of injuries due to the extension mechanism, more frequent in males, with predominance on the left side2.

The general purpose of the study was to establish the clinical-epidemiological profile of supracondylar humerus fractures, the mechanism of preponderant injury, the treatment used and the complications for paediatric patients.

Material and methodsUsing a cross-sectional analytical design, 56 files of 122 paediatric patients assisted at Hospital General Regional N 1, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social in the city of Mérida, Yucatán, from August 1, 2011 to August 31, 2013 were reviewed. Patients aged 1 to 12 were included, of both genders, with first time diagnosis of supracondylar humerus fracture. 28 politraumatised patients and 38 patients with incomplete files were excluded. Demographic variables were identified (gender, age of the child, age of the mother, place of the accident, mechanism of the injury, time between the injury and medical assistance), as well as clinical variables (affected side, type and classification of the fracture) and those related to the treatment (fixation method, complications observed, time of follow-up and recovery).

For the statistical analysis, simple frequencies and central and dispersion tendency measurements were calculated, as applicable for each variable. To analyse the association between the variables, the odds ratio (OR) was calculated, with its respective 95% confidence interval (CI). The statistically significant value was set on p<0.05 using the X2 test. For this statistical analysis, SPSS 20 software for Windows was used.

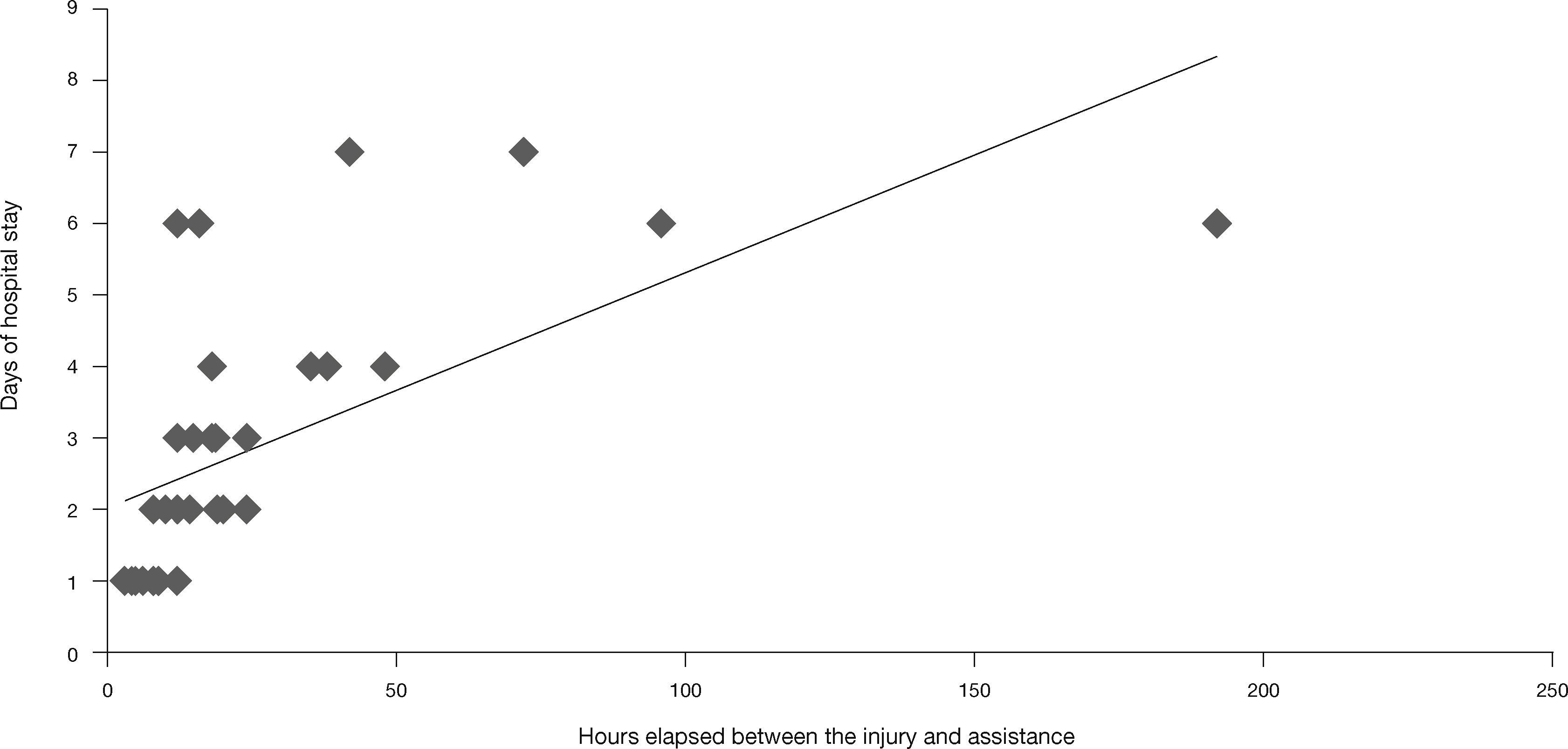

ResultsRegarding demographical data, for patients the age mean ± standard deviation was 2.6±5.33 years; males predominated females, with age means 5.1 and 5.6, respectively (Fig. 1); the most frequent injury mechanism was falling at home, with 69.6%, followed by falling in the park or during a recreational activity. 67.8% of patients came from the metropolitan area and the rest from rural communities; the dominance of the most frequent hand was the right hand, with 83.9% (Table 1). As regards the caregiver, the mother was the person who went to the Emergency Room with the child in 100% of cases; the mean age for mothers was 29.5±6.2 years; the most frequent education level was secondary school, with 32.1%, and only 8.9% with higher education; 75% of them reported to be housewives. The age and education level of the mother were not associated to any clinical variables (Table 1).

General characteristics of the study population.

| Variable | Results |

|---|---|

| Male/female | 31 (55.3%)/25 (44.7%) |

| Place of the accident | Home 39 (69.6%), park 11 (19.6%) |

| Patient's agea | 5.33±2.6 years |

| Age of the mothera | 29.5±6.2 years |

| Right/left arm affected | 24 (42.8%)/32 (57.2%) |

| Extension/flexion mechanism | 47 (83.9%)/9 (16.1%) |

| Surgical/conservative treatment | 44 (78.5)/12 (24.5) |

| Time between fall and surgerya | 23±3.6h |

a Arithmetic mean ± standard deviation.

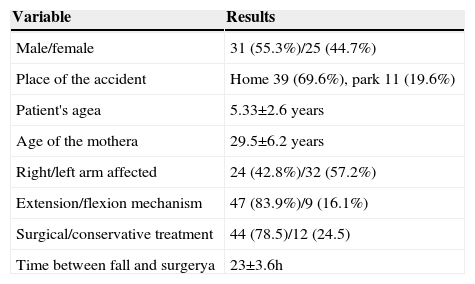

With regard to clinical variables, the most frequent injury mechanism was elbow extension in 26 males and 25 females, and flexion mechanism in 5 males and 6 females (OR5.6, 95%CI, 1.0-30.1; p=0.03); the left arm was injured in 57.2% (90.6% by extension mechanism) and the right arm in the remaining 42.8% (75% by elbow extension). The fracture was in the dominant limb in 48.2% of cases and the non-dominant limb in 51.8%. According to Gartland's classification, 50% of cases were grade III (Table 2). Twelve patients had comorbidities non-associated to the injury, the most frequent being bronchial asthma (10%) and epilepsy in 3%, none of which had acute complications at the time of the injury.

Gartland's classification in a patient with supracondylar humerus fracture in children assisted at Hospital General Regional N. 1, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social in the city of Mérida, Yucatán.

| Gartland's classification | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm | Grade In/%a | Grade IIn/%a | Grade IIIn/%a | Totaln/%a | |

| Right | 5/63 | 4/50 | 3/20 | 12/39 | |

| Male | Left | 3/37 | 4/50 | 12/80 | 19/6 |

| Totalb | 8/14 | 8/14 | 15/27 | 31/55 | |

| Right | 1/33.3 | 5/55.6 | 6/46.2 | 12/48 | |

| Female | Left | 2/66.7 | 4/44.4 | 7/53.8 | 13/52 |

| Totalb | 3/5 | 9/17 | 13/23 | 25/45 | |

All percentages have been rounded ± number of patients.

a Percentage according to the total for the gender.

b Percentages according to the total number of patients.

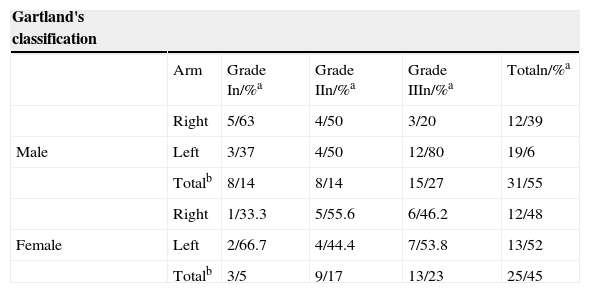

As regards treatment, it was surgical in 78.5%, using cross configuration in 100% of the surgeries (Table 3).

Treatment according to Gartland's classification in children with supracondylar humerus fracture at the HGR 1 of the IMSS in the city of Mérida, Yucatán.

| Type | Surgical | Total surgical | Conservative | Grand total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open | Closed | ||||

| n/%a | n/%a | n/%a | n/%a | n/%a | |

| I | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 11/92 | 11/20 |

| II | 8/30 | 8/44 | 16/36 | 1/8 | 17/30 |

| III | 18/70 | 10/56 | 26/64 | 0/0 | 28/50 |

| Totalsb | 26/46 | 18/32 | 44/78.5 | 12/22 | 56/100 |

All percentages have been rounded. n: number of patients.

a Percentage according to column.

b Percentages according to the total number of patients.

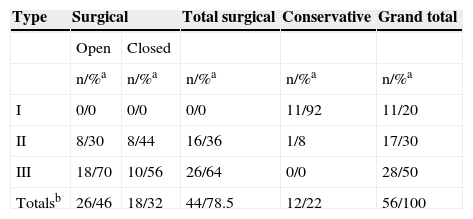

The hospital stay was 3.34 days; the time between the fall and the surgery in the cases that required surgical treatment was 23±3.6hours, with the longest time being 96hours, due the parents’ delay in seeking medical assistance, and 192hours due to the presence of an upper respiratory tract infection which delayed surgery. We found an expected correlation in the time elapsed between the fall and medical assistance, with more days of hospital stay (r=0.40; p=0.002) (Fig. 2). The time of consolidation in supracondylar humerus fractures treated with cast was 5.25 weeks compared to 5 weeks with the surgical treatment, with no significant differences between one method and the other. The time it took to withdraw the pins after surgical treatment was 4.77±0.7 weeks; the average follow-up visit was 3±1 for surgical and 2±1 for conventional treatment.

Two injuries associated to the supracondylar humerus fracture were found, consisting of an ipsilateral distal radius fracture and a contralateral humerus condyle fracture; both injuries were treated surgically.

A total of 10 complications were documented, one among patients with conservative treatment, accounting for 8.2% and consisting of the cubitus varus, and 9 complications were observed in those treated surgically; 5 of those in patients treated with closed technique, related to 4 failed attempts of reduction (9.0%) which finally changed to an open technique, and one case of cubital neurapraxia. The remaining 4 (9.0%) were presented during open reduction and were as follows: one patient with cubitus valgus, one case of radial neurapraxia, an infection of the pin trajectory and one patient who presented functional limitation in one case of failed open reduction, which required a new surgery for correction.

DiscussionThe importance of increasing knowledge about supracondylar humerus fractures lies in their high frequency in the paediatric age, and the goal of treatment is to achieve a correct fixation to ensure fast and full recovery. In this study, the mean age was found to be concordant with that reported world-wide1,16,17; 69% of accidents happened at home, more than those reported by Mathison and Agrawal1, although clinical files did not provide sufficient information to analyse the kinematics of the trauma which caused the fractures. Some studies indicate that falling from a height is the main aetiology18, a kinematic that is very unlikely at home.

Although the city of Mérida is a modern city, the family system is still traditional, which is why mothers are the people who take their children for medical assistance and most of them are housewives. We found no data in the medical literature associating maternal factors with injury risk in children. Regarding gender and affected side, our results are similar to those reported in the international literature19.

As described by Castañeda et al.20, the most frequent injury mechanism was due to extension and received Gartland's type II and III classification; said injuries were treated with closed reduction and percutaneous fixation with pins in 40.9% of cases and with open reduction in 59.1% of cases. The choice of technique was by personal decision of the physician in charge of the patient. The configuration of the pins in these fractures is controversial20; no biomechanical differences have been demonstrated between the use of crossed pins or 2 lateral entry pins; however, iatropathogenic injury of the cubical nerve is more frequent in 5-6% of cases with the use of crossed pins through medial entry through the epithroclea; in our work, crossed pins were used for 100% of cases, with no experience in the use of other configurations, and we also observed the presence of cubital neurapraxia in only one case (1.58%); despite the low prevalence of this risk, it is probable that when using the lateral configuration with 2 or 3 pins, this may decrease even more. Some studies suggest that delay of treatment does not increase surgical time or the length of hospital stay, nor does it affect the functional result8,21–23.

However, the delay between injury and medical assistance is positively correlated to the hospitalisation time, as evidenced in this study, which contributes to increasing costs for the health system and the family of the affected minor, since parents will have to distract themselves from daily activities while the minor is hospitalised, which will affect normal family dynamics. Despite the natural history of fractures with no reduction allows for proper function, there may be relevant sequels, mainly in the cubitus varus, and increased extension of the elbow24. That is why proper and timely treatment is important, and these injuries must be considered a surgical emergency.

One of the limitations in this study is its retrospective condition; however, future studies with greater explanation power may be designed based on these documented findings.

ConclusionsIn injuries caused by a fall at home or during recreational activities, where the injury mechanism is by extension, a supracondylar fracture must be suspected. In supracondylar fractures, the time between the injury and definitive medical assistance correlates to the number of days of hospital stay; although this delay does not affect the final functionality, it may lead to sequels, such as hyperextension of the elbow or the cubitus valgus.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Barrón-Torres et al. Perfil clínico-epidemiológico de las fracturas supracondíleas de húmero en pacientes pediátricos en un hospital general regional. Cirugía y Cirujanos. 2015; 83: 29-34.

Corresponding author. Calle 34N. 439 por 41, Ext Terrenos el Fénix. C.P. 97150. Mérida, Yucatán. México. Teléfono: +5299 9928 5656, ext.: 62314.