The purpose of this study is to compare, for countries with different legal environments, the degree to which boards of directors may improve corporate ethical behaviour by designing codes of ethics. These codes address issues such as a company's responsibility regarding the quality of its products and services, compliance with laws and regulations, conflicts of interest, corruption and fraud, and protection of the natural environment. Using a sample of firms from 12 countries, we obtain evidence that a greater presence of independent directors on the board leads to the existence of more complex codes of ethics. Moreover, there are significant differences between countries with high levels and countries with low levels of investor protection as regards the effectiveness of independent directors in constraining unethical behaviour by managers.

The effects of scandals involving fraud, corruption, etc. on a company's image, profitability, and long-term survival have heightened the corporate concerns regarding ethics and led to the development and implementation of ethical codes (Fan et al., 2008). These codes contribute to formalizing the corporate values, institutionalizing the guidelines for decision making within the organization, and laying down standards for responsible behaviour (McKinney et al., 2010; Singh, 2011).

Various international agencies and organizations (New York Stock Exchange, 2003; OCDE, 2004) and researchers (García-Sánchez et al., 2008; Rodríguez Domínguez et al., 2009) have considered the role of the board of directors in business ethics. In this sense, this body is responsible for supervising the senior management and for preventing and/or punishing inappropriate behaviour (Schwartz et al., 2005). The need for the involvement and commitment of the senior management and its delegate bodies to ensure the effectiveness of an ethics programme has been specially emphasized (Weaver et al., 1999).

Among the desirable features of the board's functioning for business ethics, its independence stands out. It ensures greater effectiveness in the control of the senior management (Hermalin and Weisbach, 1988; Zahra and Pearce, 1989). Furthermore, it has a decisive influence on the design of strategies for corporate responsibility (Jo and Harjoto, 2011) and ethical strategies (García-Sánchez et al., 2008). The final goal is to limit managers’ opportunities for self-benefit and the high direct costs associated with malpractice, such as fines and prison sentences, as well as negative media exposure and the consequent damage to the firm's reputation (Johnson and Greening, 1999).

On the other hand, Ravina and Sapienza (2010) argued that independent directors are economic agents, whose decisions may be influenced by their own interests. Moreover, they are subject to the institutional environment in which they operate (Bebchuk and Weisbach, 2010), which determines the type and functioning of the control mechanisms (La Porta et al., 2000).

Therefore, previous studies have suggested the importance of the board of directors regarding its active role in ethical practices, its monitoring role, and the relevance of its independence as a positive feature that may encourage stricter ethical behaviour. Based on these premises, this study examines the level of involvement of independent directors in the development of ethical codes. In other words, we attempt to determine whether independent directors promote the implementation of ethics codes addressing a wider range of issues. It also studies whether this involvement varies according to the level of investor protection present in the institutional environment in which the company operates.

Along this line, the level of investor protection is considered to be one of the most important factors among the characteristics of the institutional environment. It may contribute to explaining the presence or absence of opportunistic behaviour by managers (Benos and Weisbach, 2004) and/or their misappropriation of investors’ rights (Dyck and Zingales, 2004). Such expropriation or opportunistic behaviour by internal agents can take the form of the personal use of company assets, acquisition strategies that destroy value, accounting manipulation, bribery, corruption, etc. (Morck et al., 1990). However, there is no clear evidence of interaction with the institutional environment that could influence the behaviour of independent directors.

Previous research has produced conflicting results; although a substitutive relationship has been shown to exist between the institutional environment and the characteristics of the board of directors (Aggarwal et al., 2009), many authors have observed a lower degree of opportunistic behaviour by managers, such as accounting manipulation or information asymmetries, in countries where the investor protection is stronger (Ball et al., 2000; Bhattacharya et al., 2003; Leuz et al., 2003; Bushman et al., 2004). On the other hand, there is no empirical evidence of an interaction between the two factors with respect to the design of corporate strategies (Bebchuk and Weisbach, 2010). Therefore, we propose that countries with strong investor protection offer a more suitable context for independent directors in order to implement more complex codes, whereas these directors in countries with less investor protection would face greater reluctance to implement mechanisms that restrain opportunistic behaviour.

Taking these considerations into account, our study makes a new contribution that copes with both perspectives: the importance of the board's independence as a corporate governance mechanism in the implementation of ethics codes and the difference in involvement according to the context in which the company operates.

The two perspectives are combined in the proposal of our research model, in which the scope of ethics codes is expressed as a function of board independence, its interaction with the investor protection existing in the environment, and some control variables. To test this model, we use a panel data sample made up of 5380 observations for an average of 760 companies from 12 countries, for the time period 2003–2009. The financial data were obtained from Compustat, whereas the data on corporate governance and ethics were extracted from the EIRIS database.

Our findings point out that independent directors positively influence the implementation of codes with a wider scope, with an ethical commitment that extends beyond the discrimination and the adequate relationships with providers and clients. This compromise encompasses a wider range of ethical issues, affecting the sustainable use of resources and the overall relationship with society. The findings obtained are in accordance with previous studies (e.g. Ibrahim and Angelidis, 1995; Johnson and Greening, 1999), which emphasize the potential link between board independence and willingness to show the firm's ethical behaviour.

Additionally, we detect that the investor protection existing in the corporate context in which the company operates influences the extent of the impact of independent directors on the development of more complex codes. Hence, directors of companies in countries with a lower level of investor protection have more difficulty in implementing ethical codes with a wider range of contents. This result reinforces the previous evidence found by Beck et al. (2003) or Shen and Chih (2005), which show a complementary link between internal and external mechanisms of corporate governance.

This study is structured as follows. The section “Ethical codes” describes ethical codes as a mechanism for combating unethical practices and the importance of the board in ensuring their effectiveness. The section “The ethical role of independent directors” contains the main research hypotheses, related to the role played by independent directors in implementing more complex ethical codes and the stronger influence expected in those countries with greater investor protection. The fourth section presents the sample analysed, the variables used to test the hypotheses, and the models proposed. The section “Empirical analysis” explains the results obtained after estimating the original models and undertaking some sensitivity analyses, and finally section “Conclusions” summarizes and concludes.

Ethical codesBusiness ethics can be understood as the set of values, norms, and principles that seek to achieve respect for the rights generally recognized within a society. To institutionalize ethical conduct within corporations, specific codes have been developed. According to Kaptein and Schwartz (2008, p. 113), such a code should constitute “a distinct and formal document containing a set of prescriptions developed by and for a company to guide present and future behaviour on multiple issues of at least its managers and employees toward one another, the company, external stakeholders and/or society in general”.

More specifically, codes transmit ethical values to members of the organization (Wotruba et al., 2001), offering them moral guides or anchors when new and confusing situations are encountered in the workplace (Chua and Rahman, 2011) and in decision making (Urbany, 2005).

The existence of a code of ethics was initially considered as preventive medicine against fraud, misappropriation, embezzlement, nepotism, cronyism, favouritism, abuse of influence, abuse of power, the illegal financing of political parties, the misuse of privileged information, workplace mobbing, defamation, false advertising, negligent discrimination, and environmental actions, among other unethical practices. However, several studies have shown that the mere existence of such a code does not guarantee ethical business behaviour (Vethouse and Kandogan, 2007; Kaptein and Schwartz, 2008).

In this respect, Ibrahim et al. (2009), Kaptein (2011), and Singh (2011) observed that the existence of training programmes and communication channels to familiarize users with the content and intent of this code will improve its effectiveness. It has been shown that the key factor in successfully influencing the behaviour of company staff is the actual content of the ethical code; this is what determines its impact on managers’ judgements and decisions.

Additionally, the factor of corporate governance is of crucial importance in ensuring the effectiveness of codes of ethics. Many previous studies on the practice of corporate ethics have highlighted the need for the involvement and commitment of the senior management and its delegate bodies to ensure the effectiveness of an ethics programme (Weaver et al., 1999). Maintaining organizational integrity and ethics is assumed to be among the skills that directors and managers should actively practice (Vethouse and Kandogan, 2007). Consequently, according to Bonn and Fisher (2005), boards and senior management need actively to promote, manage, and monitor a culture that emphasizes ethical behaviour and integrity within the organization. They should evaluate its current strategies, policies, and procedures and investigate whether ethical behaviour is encouraged and the company's ethical values are reflected. The primary goal should be to develop an ethical code setting out the recommendations and principles to be followed in a wide range of situations. This is regarded as the most important factor underlying the achievement of more ethical business behaviour (Ibrahim et al., 2009; Kaptein, 2011; Singh, 2011).

According to Schwartz et al. (2005), board members are ultimately responsible for the selection, permanence, and discipline of senior officers and must take their ethical obligations into account. Furthermore, the main codes of corporate governance applicable in different countries state that among the board's functions is that of ensuring ethical conduct within the organization (Aguilera and Cuervo-Cazurra, 2009).

The ethical role of independent directorsIndependent directors have a particular responsibility to safeguard the interests of shareholders and investors. They supervise the senior management and ensure that business ethics form part of the organizational culture (Rodríguez Domínguez et al., 2009). One ethical policy is to encourage the adoption of complex ethical codes to restrain inappropriate actions and maintain the firm's good image and long-term survival (Singh, 2011).

In addition to their stipulated functions, independent directors are argued to be the best equipped and most appropriate board members to take responsibility for compliance with the regulations and to ensure the ethical behaviour of the firm (Ibrahim and Angelidis, 1995). This is due to their greater objectivity and independence in analysing the management process (Prado-Lorenzo and García-Sánchez, 2010), as well as the impact of their success or otherwise, in this respect, on their personal standing (Frías-Aceituno et al., 2012).

Fama and Jensen (1983) and Lorsch and Maciver (1989) argued that the main benefits enjoyed by independent directors are prestige, reputation, job openings, and networking opportunities. Directors who perform their duties effectively and efficiently are more likely to be rewarded, while those who work in companies that obtain poor results will tend to lose privileges.

Homstrom (1999) observed that concerns about the firm's reputation can create incentives for directors to avoid risky actions that could have negative consequences for their future as external directors. Any loss of reputation would reduce their chances of being offered another such post (Srinivasan, 2005; Fich and Shivdasani, 2007) and even of retaining their present one (Fahlenbrach et al., 2010). In addition, these directors will have a more critical view of the corporate activities that may be carried out, having greater freedom to defend costly and/or unpopular decisions (Arora and Dharwadkar, 2011).

As mentioned previously, their role may be especially outstanding when dealing with ethical issues. They may be less reluctant to investigate/prevent cases of fraud (Beasley, 1996). Furthermore, they will be more receptive to the demands of external groups for improved ethical behaviour by the company and will seek to encourage internal groups to meet the goals of good governance (Fombrum and Shanley, 1990). Given that (1) one of the board's functions concerns ensuring ethical conduct within the organization (Aguilera and Cuervo-Cazurra, 2009), (2) their ethical functions may be better fulfilled in the presence of independent directors (Ibrahim and Angelidis, 1995), and (3) ethical issues are mainly dealt with through codes of ethics, we posit our first research hypothesis:Hypothesis 1 The presence of independent directors encourages the implementation of ethical codes.

A further stage in this analysis is to determine whether the involvement of independent directors in the definition of policies on business ethics is similar in all corporate environments (Bebchuk and Weisbach, 2010). Firstly, this debate is based on the arguments of Ravina and Sapienza (2010), for whom the decisions of independent directors are determined by the satisfaction of their own utility function as economic agents. Furthermore, the earlier empirical evidence shows that the functioning of the internal mechanisms of corporate governance (e.g. boards and their independence) cannot be understood without considering the mechanisms associated with the institutional environment proposed by La Porta et al. (1997, 1998, 2000).

La Porta et al. argued that the laws protecting the rights of investors and the degree of effective implementation of these laws are the main determinants of the way in which corporate governance develops. Investor protection is understood as the degree to which business legislation and its application protect investors from the expropriation that may be conducted by insiders. Greater legal protection for investors would restrain the behaviour of directors, limiting their chances to engage in opportunistic behaviour and preventing insiders from obtaining private benefit (Hart, 1995; Djankov et al., 2005).

Therefore, the extent of investor protection may influence directors’ impact on ethical issues, particularly when the directors come from outside the company, like independent ones. More specifically, there are three possible scenarios regarding the moderating role of investor protection in the ethical commitment of independent directors. In the first such scenario, the least plausible one, the effect would be neutral. These directors would perform their roles in the same way worldwide, with no influence being exerted by the institutional environment. The other two scenarios require us to consider systemic variations in directors’ behaviour, as a result of the incentives provided in different institutional settings.

The second scenario assumes a substitutive relationship between corporate governance mechanisms. Along this line, Doidge et al. (2004) suggested a negative relationship between the strength of firm-level governance and country-level laws. Thus, the independent directors of companies located in countries with less investor protection would be expected to take a more active role in developing complex ethical codes than other directors. They would seek the adoption of better firm-level governance to offset the weaknesses in the law or in its application and indicate their intention to offer more rights to investors.

The third scenario follows the complementary argument proposed by Doidge et al. (2004), according to which the two mechanisms are mutually reinforcing. In this situation, in countries where the regulatory and business environment offers greater investor protection, independent directors are expected to take a more active role in developing complex ethical codes than the other directors. Within this relationship, the combination of interventionism by the independent directors and the strength of the legal and judicial protection of investor rights would ensure the highest degree of investor protection.

Empirically, although there is no clear evidence of the interaction with the institutional environment that could impact on the behaviour of independent directors, the first scenario should be rejected. Rather, previous research has revealed the existence of substitutive (Denis and Kruse, 2000; Huson et al., 2001; Aggarwal et al., 2009) and complementary effects (Claessens et al., 2000; Gul et al., 2002; Beck et al., 2003; Leuz et al., 2003; Shen and Chih, 2005) between diverse internal and external mechanisms of corporate governance.

In this paper, we argue that the effect of the level of investor protection on managers’ ethical commitment will be complementary, as the consequence of rational decisions made by directors in their role as economic agents. More specifically, we suggest that in the decisions taken as economic agents, managers will realize that the development of ethical codes is the outcome of demands in this respect made by social activists, regulators, environmental legislative pressure, etc. Their implementation is also the result of external pressure from investors and other capital market agents, who seek to protect the company and secure it against potential unethical conduct (Stevens et al., 2005; Robertson et al., 2013).

Moreover, managers will consider that the positive outcome obtained from effective codes is not limited to the company's internal affairs, i.e., achieving more ethical behaviour, developing a comprehensive ethical culture, and increasing employee satisfaction. It will also be transferred to its external representation, enhancing institutional legitimacy and improving the organizational approach to public accountability (Valentine and Fleischman, 2008). All of these aspects promote a positive external image of the firm; they influence shareholders’ perceptions, generate reputational benefits (Stevens et al., 2005), and improve financial performance (Weigelt and Camerer, 1988; Stevens et al., 2005).

Both the pressure from investors and the benefits generated by the adoption of a code of ethics are more apparent in capital markets that are more developed and transparent. Given that these characteristics are usually typical of countries with higher levels of investor protection (La Porta et al., 1998), independent directors will obtain greater benefits from their involvement in ethical issues in these countries. In other words, these directors will view a code of ethics as a crucial component of the company's ethical infrastructure. A code will contribute to the development of a culture and an image that will maintain or restore the firm's ethical reputation vis-à-vis its stakeholders, especially investors (McKinney et al., 2010). In addition, it will help raise public confidence in the firm's conduct, influencing external impressions of its directors’ work, and thus help them to achieve greater professional recognition and provide more opportunities for participation in other boards of directors.

Therefore, we suggest that the business environment for companies located in countries with strong investor protection will be more suitable for independent directors to assume a more interventionist outlook with respect to the firm's policy on ethical issues. In those contexts, they enjoy greater flexibility to implement a more complex ethical code, thereby enhancing investor protection. On the contrary, the managers of companies located in countries with less investor protection have greater potential to obtain private benefits (Nenova, 2003; Dyck and Zingales, 2004); thus, they will present stronger opposition to mechanisms that limit opportunistic conduct (Renders and Gaeremync, 2007). On this line, the following hypothesis is proposed:Hypothesis 2 The implementation of ethical codes on behalf of independent directors is more active in countries with stronger investor protection.

The study population is comprised of the listed European, US, and Canadian companies for which economic–financial data are available in Compustat, together with the data relating to corporate governance and ethical codes published by Ethical Investment Research and Information Services (EIRIS). Merging the two databases provided a sample of 5380 observations for an average of 760 companies from 12 countries, for the analysis period 2003–2009. The panel data sample is non-balanced, as not all companies were observed for all the financial years in question; thus, the number of firms observed ranged from 617 to 907 for this period.

The EIRIS database contains information on the corporate social responsibility practices of the 3000 largest companies worldwide. The information is mainly obtained from public data, although questionnaires are used to ascertain unpublished or unclear data. Subsequently, these data are checked by external experts, unrelated to EIRIS and the companies in question. This methodology has been awarded the AI CSRR Voluntary Quality Standard. Its main customers include the FTSE indices, the stock exchanges in Johannesburg and Mexico, and brokers, asset managers, etc. in Europe, North America, Australia, and Asia.

As shown in Table 1, there is a bias in the sample distribution due to the weight of the number of companies in the USA and the UK. This results from the size bias of the companies making up the EIRIS database. From the temporal point of view, the highest number of observations was obtained for 2008.

Sampling distribution, by countries.

| Country | Sampling period | Total | Frequency | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |||

| Germany | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 44 | 42 | 30 | 150 | 2.79% |

| Canada | 48 | 54 | 50 | 57 | 54 | 54 | 56 | 373 | 6.93% |

| Denmark | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 47 | 0.87% |

| Finland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 56 | 1.04% |

| France | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 112 | 4.98% |

| Italy | 34 | 35 | 39 | 41 | 42 | 41 | 36 | 268 | 4.98% |

| Netherlands | 23 | 25 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 23 | 172 | 3.20% |

| Norway | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 0.56% |

| Spain | 32 | 34 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 36 | 36 | 250 | 4.65% |

| Sweden | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 39 | 39 | 119 | 2.21% |

| UK | 115 | 127 | 129 | 136 | 140 | 140 | 130 | 917 | 17.04% |

| USA | 365 | 382 | 412 | 422 | 424 | 448 | 433 | 2886 | 53.64% |

| Total | 617 | 657 | 693 | 754 | 888 | 907 | 864 | 5380 | |

The dependent variable, CElevel, was defined to represent the implementation of a code of ethics in two ways: its existence and its level of application. This is an ordinal variable that takes values between 0 and 4 by identifying the level or inclusivity of the ethical code.

- •

A value of 1 represents limited inclusion, i.e., the code refers to a very limited number of aspects, such as conflicts of interest, corruption, and bribery.

- •

A value of 2 is a basic level, incorporating, in addition to the first level, recommendations on questions such as discrimination, occupational hazards, the work environment, and the confidentiality of information.

- •

A value of 3, the intermediate level, incorporates, as well as the aspects addressed in the two previous levels, the principles and values related to relationships with customers, suppliers, and competitors.

- •

A value of 4, the advanced level, adds references to the sustainable use of resources, relations with society, and any other value that forms part of the corporate culture.

- •

The value of 0 is assigned to companies that do not express any ethical commitment.

Table 2 shows that 96.7% of the companies listed had implemented a code of ethics. Regarding the level of these codes, 12.7% were classed as limited or basic, while 27.6% were intermediate and 56.4% advanced.

Level of application and awareness of ethical codes.

| 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | Absolute frequency | Relative frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 77 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 18 | 15 | 5 | 149 | 3.3 |

| 1 | 106 | 37 | 30 | 23 | 27 | 24 | 14 | 261 | 5.0 |

| 2 | 60 | 49 | 57 | 59 | 68 | 68 | 54 | 415 | 7.7 |

| 3 | 130 | 213 | 226 | 220 | 231 | 243 | 231 | 1494 | 2.6 |

| 4 | 244 | 347 | 368 | 441 | 544 | 557 | 560 | 3061 | 5.4 |

Regarding the evolution in this field, Fig. 1 shows that there has been a significant decrease in the number of companies that either do not have a code of ethics or have one of only limited reach. On the contrary, a corresponding increase occurred in the numbers of companies classified as intermediate or advanced in this respect. Furthermore, during the period examined, the number of companies of which the ethical codes were considered basic remained unchanged, but there was a very significant increase in the number of companies that implemented advanced codes of ethics, in terms of the recommendations made.

Independent and control variablesTo test hypothesis H1, we defined as the independent variable %INDEP, representing the percentage of independent directors on the board of directors of each company. A time lag was applied to the variable to avoid potential problems of endogeneity arising from the fact that the more ethical companies may promote a greater presence of independent directors on their boards.

In analysing hypothesis H2, we must first define the institutional environment. In this respect, Chong and López-de-Silanes (2007), among others, suggested that investor protection should be defined in terms of: (1) the tradition and the existence of laws that safeguard the interests of investors and (2) the characteristics of the judicial institutions created to ensure their implementation and enforcement; in this sense, judicial support for the applicable rules and laws has the power to prevent, or at least limit, the expropriation of investors.

The underlying legal tradition is the foundation of basic legal rights, including the protection of property rights, and the bedrock of corporate and securities law. La Porta et al. (1998) classified legal traditions into two families, common law and civil law. Common law countries developed a legal tradition based on customary law, characterized by less reliance on the statutes and a preference for contracts and private litigation to resolve disputes. In contrast, civil law countries are characterized by greater explicit reliance on laws and procedural codes and by the preference for the state to regulate the resolution of private disputes. In this sense, common law environments offer greater protection for investors because of their strong focus on private contracts and the protection of property rights.

Therefore, our first variable in investor protection is that of the legal tradition, and this is encoded by a dummy variable that takes the value 1 for countries with a common law legal tradition and the value 0 otherwise.

A second level of investor protection is provided by commercial law, in particular the legal mechanisms that protect investors, alleviating the agency problems that may occur. La Porta et al. (1998) developed an index of anti-director rights on the basis of the presence/absence of six specific elements of investor protection. This index uses six values to measure the ease with which investors can exercise their rights in response to opportunistic behaviour.

The third level of protection is based on the existence of other parameters of the legal system (Deffains and Guigou, 2002), such as mechanisms to enforce the existing regulations, which can alleviate the firm's ethical problems. In this respect, Defond and Hung (2004) and Durnev et al. (2004) observed that the strength of the enforcement control mechanisms is more significant than the mere existence of a broad set of laws governing them.

To characterize the mechanisms supporting legal provisions, we shall use two indices proposed by La Porta et al. (1998) to assess a country's legal framework: the index of judicial efficiency and the index of law and order. The first index rates the independence and professionalism of the judiciary in all kinds of proceedings, together with the adequacy of its time scales, especially as regards the reasonableness of judicial delays. The law and order index concerns the generality and non-arbitrariness of rules, their comprehensiveness, their fairness, etc. Both of these enforcement control mechanisms are true determinants of the protection of investors’ rights because they determine the responsibility of company managers and directors (La Porta et al., 1998).

To operationalize investor protection and make it interactive with the proxy for independence (following Hillier et al., 2011), we created three sub-indices: (1) DCL, which takes the value 1 if the firm is located in a common law country and the value 0 if it is located in a civil law country; (2) DAR, which takes the value 1 if the firm is located in a country with investor protection rights that are more restrictive on directors than the median level in the sample and 0 otherwise; and (3) DEF, which takes the value 1 if the firm is located in a country where the index of application of the law is above the median and 0 otherwise – the latter index is obtained as the sum of the indices of judicial efficiency and of law and order. Finally, we take as a proxy for effective investor protection the sum of the three dummy variables – DCL, DEF, and DAR – and construct a new dummy variable, DINV_PROTEC, which takes the value 1 if the firm is located in a country with above-average investor protection and 0 otherwise.

Additionally, in order to test the role of independent directors in each investor protection system, we interacted the percentage of independent directors with the investor protection dummy. This interacted variable is labelled %INDEP*DINV_PROTEC and identifies the percentage of independent directors in countries with an above-average level of investor protection. As with the %INDEP variable, a time lag is applied to the variable in order to avoid problems of endogeneity.

To eliminate bias from the results, we considered a set of control variables previously shown to be effective in this respect: board diversity, size, and activity, company size, level of borrowing, and growth opportunities.

The numeric variable %FEM represents the percentage of female directors on the company board. Gender diversity plays a very important role in the ethical commitment of companies, due to differences in the ethical frameworks used by men and women in their moral judgements (Harris, 1989; Ibrahim et al., 2009). According to previous studies (Stultz, 1979; Ibrahim and Angelidis, 1994; García-Sánchez et al., 2008; Rodríguez Domínguez et al., 2009), female directors are usually more sensitive to ethical issues.

The numeric variable BOARDSIZE represents the total number of directors. In general, large boards of directors have more serious agency problems and a greater need for ethical codes (García-Sánchez et al., 2008). The BOARDSIZE2 variable is the square of the above and is taken into consideration because authors such as Diwedi and Jain (2005) incorporated this value into their analyses in order to test for a possible non-linear relationship. In other words, the general behaviour of the board may be modified when a certain board size is exceeded.

The BOARDACT numeric variable measures the number of board meetings in each year. The effect of this variable is not clear a priori. On the one hand, Lipton and Lorsch (1992) argued that active directors are more effective, presenting a greater predisposition towards corporate social responsibility. However, a large number of meetings may simply evidence inoperability and the fact that the directors are taking on too much, negatively affecting business management (Vafeas, 1999).

The indicator of company size, FIRMSIZE (the logarithm of total assets), is valuable because of this factor's effect on the processes of corporate social legitimation, as highlighted in studies such as Hackston and Milne (1996), Archel and Lizarraga (2001), Gray et al. (2001), and Archel (2003). The level of company debt, LEVERAGE (the ratio of debt to equity), is another factor associated with the development of codes of ethics, especially as a means of prevention and response to agency conflicts that may arise. With respect to growth opportunities, companies with high MTB values (calculated as the ratio between the market value and the book value of business assets), comparably with expectations for the legitimation process, are expected to develop ethical codes aimed at reducing the problems of asymmetric information; this enables them to regulate employee behaviour (Larrán and García-Meca, 2004; Gandía and Pérez, 2005). Finally, the industry sector variable is introduced in order to control the effect of the firm's economic activity on the level and impact of ethical codes; some industry sectors are more likely to establish internal rules to prevent potential unethical situations that may occur in relation to the specific activity of the sector (García-Sánchez et al., 2008).

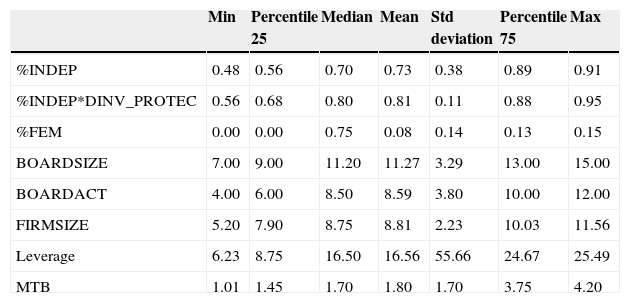

Table 3 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the variables proposed for analysis. As can be seen, on average boards are composed of 11 directors, presenting a level of activity of 9 meetings per year. The average proportion of independent directors is 72.59%, with higher levels in institutional environments featuring greater investor protection (81.40%). The average presence of female directors is very low (7.98%). The majority of observations (60.6%) refer to institutional settings in which investor protection is higher than the average level for our sample.

Descriptive statistics.

| Min | Percentile 25 | Median | Mean | Std deviation | Percentile 75 | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %INDEP | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.38 | 0.89 | 0.91 |

| %INDEP*DINV_PROTEC | 0.56 | 0.68 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.88 | 0.95 |

| %FEM | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| BOARDSIZE | 7.00 | 9.00 | 11.20 | 11.27 | 3.29 | 13.00 | 15.00 |

| BOARDACT | 4.00 | 6.00 | 8.50 | 8.59 | 3.80 | 10.00 | 12.00 |

| FIRMSIZE | 5.20 | 7.90 | 8.75 | 8.81 | 2.23 | 10.03 | 11.56 |

| Leverage | 6.23 | 8.75 | 16.50 | 16.56 | 55.66 | 24.67 | 25.49 |

| MTB | 1.01 | 1.45 | 1.70 | 1.80 | 1.70 | 3.75 | 4.20 |

| Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|

| Absolute | Relative | |

| DINV_PROTEC | 3.259 | 60.6% |

“%INDEP” is the percentage of independent directors on the board. It interacts with the DINV_PROTEC variable to identify the role of independent directors in companies located in countries with above-average levels of investor protection. “%FEM” represents the percentage of women on the board of directors. “BOARDSIZE” is a numeric variable representing the total number of board members, internal and external. “BOARDACT” is a numeric variable expressing the number of board meetings held each year. “FIRMSIZE” is the size of the corporation, measured by the logarithm of its total assets. “Leverage” is the level of corporate debt represented as the ratio external funds/equity. “MTB” represents the market value of the company compared to its book value.

Table 3 also shows that the average MTB ratio is 1.80, i.e., the market value exceeds the book value of the business assets, indicating that investors expect to obtain added value in the future, in view of the current value of company assets. Finally, these companies have an average debt ratio of 16.56%, which is notably lower than the 21.58% observed in other studies with international samples (Brockman et al., 2013). This variable has a standard deviation of 55.66, indicating a high degree of dispersion. To test the effect of this disparity, two analyses were conducted, the first with the original values and the second after eliminating outliers. As no changes were observed in the results obtained, we decided to retain the original values in the analysis.

Analytic modelFrom the hypotheses set out and the variables defined above, the following models are proposed:

where“CElevel” is an ordinal variable that takes a value from 0 to 4, depending on the level of application of the company's ethical code.

“%INDEP” is the percentage of independent directors on the board at t−1. This is interacted with the variable “DINV_PROTEC” to identify the role played by independent directors at t−1 in companies located in countries where the levels of investor protection are above average.

“%FEM” represents the percentage of female directors on the board.

“BOARDSIZE” is a numerical variable that represents the total number of directors, both internal and external, on the board.

“BOARDSIZE2” is a numerical variable that represents the square of the total number of directors, both internal and external, on the board.

“BOARDACT” is a numerical variable that reflects the number of board meetings held each year.

“FIRMSIZE” is the size of the company, expressed as the logarithm of its total assets.

“Leverage” is the level of company debt, represented by the borrowing/equity ratio.

“MTB” is the market-to-book value of the company.

“Sector” is a numerical variable that identifies the area of activity of the company.

“Year” is a dummy variable vector identifying the time period analysed.

The dependent variable CElevel takes values between 0 and 4, such that 0 represents the absence of a code of ethics and 4 represents an advanced ethical code, with the highest rating. Accordingly, the dependent variable is an ordinal value. Each value of “CElevel” generates a continuous evaluation of the company, which is incorporated into an unobserved latent variable, which we term “CElevel*”. This variable has a linear shape and is dependent on the same independent and control variables:

As there are a limited number of categories of “CElevel”, this variable presents various cut-off points, delimiting each category, as follows:

Wooldridge (2002) proposed two approaches for estimating panel data models with an ordinal dependent variable. The one that is most commonly used assumes that the μit and ηi errors are normally distributed and is estimated by maximum likelihood. This is the approach implemented in STATA by Rabe-Hesketh et al. (2001) and improved by Frechette (2001a, 2001b). The programme estimates a probit model with random effects. These models are widely used in analyses of rating agencies’ classifications (Afonso et al., 2007).

Empirical analysisBasic estimationsTable 4 summarizes the bivariate correlations for the variables considered in the analysis. The most significant relationships with the dependent variables are those for firm size, the size and degree of activity of the board, the presence of independent directors, and the proportion of female directors.

Bivariate correlations.

| CElevel | %INDEP | DINV_PROTEC | %INDEP*DINV_PROTEC | %FEM | BOARDSIZE | BOARDACT | FIRMSIZE | Leverage | MTB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %INDEP | 0.112** | |||||||||

| DINV_PROTEC | 0.072** | 0.280** | ||||||||

| %INDEP*DINV_PROTEC | 0.095** | 0.321** | 0.978** | |||||||

| %FEM | 0.055** | 0.259** | 0.148** | −0.127** | ||||||

| BOARDSIZE | 0.026 | −0.275** | −0.071** | −0.072** | −0.101** | |||||

| BOARDACT | 0.035* | −0.023 | −0.005 | 0.015 | 0.045** | 0.031* | ||||

| FIRMSIZE | 0.148** | 0.087** | 0.137** | 0.145** | 0.055** | 0.324** | 0.102** | |||

| Leverage | −0.019 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.013 | −0.009 | −0.015 | −0.008 | 0.121** | ||

| MTB | −0.008 | −0.004 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.015 | −0.016 | 0.001 | −0.02 | 0.001 |

“CElevel” is an ordinal variable, taking values from 0 to 4, according to the level of inclusion or application of the firm's code of ethics. “%INDEP” is the percentage of independent directors on the board. It interacts with the DINV_PROTEC variable to identify the role of independent directors in companies located in countries with above-average levels of investor protection. “%FEM” represents the percentage of women on the board of directors. “BOARDSIZE” is a numeric variable representing the total number of board members, internal and external. “BOARDACT” is a numeric variable expressing the number of board meetings held each year. “FIRMSIZE” is the size of the corporation, measured by the logarithm of its total assets. “Leverage” is the level of corporate debt represented as the ratio external funds/equity. “MTB” represents the market value of the company compared to its book value.

Table 5 summarizes the results obtained from the two analytic models proposed: Model 1 includes the proxy for independent directors overall, while Model 2 also includes the interaction of this variable with the level of investor protection.

Explanatory models of the level of application of codes of ethics.

| CElevelit=β0+β1%INDEPit−1+β2DINV_PROTECit+β3%FEMit+β4BOARDSIZEit+β5BOARDSIZE2it+β6BOARDACTit+β7FIRMSIZEit+β8Leverageit+β9MTBit+β10Sectorit+βinYear+μit+ηi | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CElevelit=β0+β1%INDEPit−1+β2%INDEP*DINV_PROTECit−1+β3DINV_PROTECit+β4%FEMit+β5BOARDSIZEit+β6BOARDSIZE2it+β7BOARDACTit+β8FIRMSIZEit+β9Leverageit+β10MTBit+β11Sectorit+βinYear+μit+ηi | ||||||||||

| Independent variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||||

| Coef. | Std. Err. | VIF | Z | p>|z| | Coef. | Std. Err. | VIF | Z | p>|z| | |

| %INDEP | 0.27 | 0.09 | 1.23 | 3.05 | 0.002 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 1.27 | 2.66 | 0.008 |

| %INDEP*DINV_PROTEC | 1.37 | 0.52 | 5.24 | 2.65 | 0.008 | |||||

| DINV_PROTEC | 0.12 | 0.13 | 1.19 | 0.91 | 0.362 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 1.02 | −1.71 | 0.087 |

| %FEM | 0.75 | 0.07 | 1.18 | 10.63 | 0.000 | 0.73 | 0.07 | 1.18 | 10.3 | 0.000 |

| BOARDSIZE | 0.20 | 0.05 | 4.23 | 3.81 | 0.000 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 4.28 | 3.46 | 0.001 |

| BOARDSIZE2 | −0.05 | 0.27 | 1.09 | −0.17 | 0.866 | −0.05 | 0.28 | 1.09 | −0.19 | 0.851 |

| BOARDACT | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 1.95 | 0.051 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.03 | 1.69 | 0.091 |

| FIRMSIZE | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1.15 | 4.97 | 0.000 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1.15 | 4.55 | 0.000 |

| Leverage | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.01 | −1.64 | 0.101 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.01 | −1.63 | 0.103 |

| MTB | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 0.08 | 0.940 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 0.05 | 0.961 |

| SECTOR | −0.09 | 0.04 | 1.02 | −2.03 | 0.042 | −0.91 | 0.40 | 5.15 | −2.25 | 0.024 |

| D2005 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 4.13 | −3.21 | 0.001 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 4.17 | −3.01 | 0.003 |

| D2006 | 0.96 | 0.07 | 1.21 | 13.32 | 0.000 | 0.94 | 0.07 | 1.21 | 12.75 | 0.000 |

| D2007 | 1.21 | 0.07 | 1.23 | 16.48 | 0.000 | 1.18 | 0.07 | 1.23 | 15.79 | 0.000 |

| D2008 | 1.17 | 0.07 | 1.24 | 15.97 | 0.000 | 1.13 | 0.08 | 1.24 | 14.67 | 0.000 |

| D2009 | 1.50 | 0.10 | 1.19 | 14.61 | 0.000 | 1.47 | 0.10 | 1.19 | 14.26 | 0.000 |

| _cut1 | −0.16 | 0.41 | −0.39 | 0.699 | −0.22 | 0.46 | −0.48 | 0.633 | ||

| _cut2 | 0.67 | 0.41 | 1.66 | 0.097 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 1.35 | 0.178 | ||

| _cut3 | 1.40 | 0.41 | 3.45 | 0.001 | 1.34 | 0.46 | 2.94 | 0.003 | ||

| _cut4 | 3.03 | 0.41 | 7.43 | 0.000 | 2.97 | 0.46 | 6.49 | 0.000 | ||

| rho | 0.71 | 0.02 | 44.99 | 0.000 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 37.47 | 0.000 | ||

| Log-likelihood | −3814.89 | −3810.84 | ||||||||

| Chi-squared | 542.02 | 550.13 | ||||||||

| p value | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||

“CElevel” is an ordinal variable, taking values from 0 to 4, according to the level of inclusion or application of the firm's code of ethics. “%INDEP” is the percentage of independent directors on the board. It interacts with the DINV_PROTEC variable to identify the role of independent directors in companies located in countries with above-average levels of investor protection. “%FEM” represents the percentage of women on the board of directors. “BOARDSIZE” is a numeric variable representing the total number of board members, internal and external. “BOARDSIZE2” is a numeric variable representing the square of the total number of board members, internal and external. “BOARDACT” is a numeric variable expressing the number of board meetings held each year. “FIRMSIZE” is the size of the corporation, measured by the logarithm of its total assets. “Leverage” is the level of corporate debt represented as the ratio external funds/equity. “MTB” represents the market value of the company compared to its book value. “SECTOR” is a numeric variable identifying the firm's sector of activity.

Statistically significant coefficients are shown in bold.

The fit information for the estimated models is determined by the log likelihood, which controls the representativity of each equation. Specifically, to establish the likelihood, a χ2 test is conducted of the significance of the difference between the value of the log likelihood of the model with only the constant and that of the full model. The null hypothesis is that the coefficients of all the variables included in the final model except the constant are equal to zero. The alternative hypothesis is that the coefficients are significantly different from zero. If the probability χ2 associated with the test value is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis should be rejected, accepting that the final ordinal model is significant from the econometric point of view (Hair et al., 1998). The level of representativity is determined using the Wald test, which, according to the levels of significance obtained will lead us to accept or reject the model in question. The p-values of all the models are statistically significant at the confidence level of 99%. This means that the equations adequately explain the level of application of the ethical codes examined.

Regarding the effect of the explanatory variables, the z test determines whether the coefficient of each of the independent and control variables considered independently has a value that is significantly different from 0. In other words, it evidences whether it has a real effect on the introduction and level of application of the codes of ethics. To do so, the probability of occurrence should be less than 0.05. In addition, we show the VIF values for the independent variables in order to analyse the possible multicollinearity associated with the consideration of linear and quadratic measures of the variables or the interaction among them. As can be seen in the results table, the VIF values are less than 5, so the existence of multicollinearity is rejected.

In this respect, for Model 1 in Table 5, the variable %INDEP has a positive and significant impact, at the confidence level of 99%, on the dependent variable CElevel. Therefore, hypothesis H1 is accepted.

Moreover, Model 2 in Table 5 indicates that the variables %INDEP and %INDEP*DINV_PROTECT have a positive impact on CElevel, at the confidence level of 95%. Taken together, these results show that the independent directors of companies located in countries with high levels of investor protection have a stronger significant and positive effect on the implementation of an ethical code with a higher level of application (coef=0.24+1.37=1.61) than those in companies located in weaker legal environments (coef=0.24). In conclusion, the results obtained for Model 2 lead us to accept hypothesis H2.

Our test of hypothesis H1 shows that independent directors play an important role in the implementation of ethical codes, thus carrying out the duty assigned by shareholders regarding the supervision of the management team (Jensen, 1993). These results reinforce the previous empirical evidence obtained to the effect that these directors are more motivated to demonstrate the firm's ethical behaviour (Ibrahim and Angelidis, 1995). Accordingly, they may encourage insiders to achieve their goals by means of good governance (Fombrum and Shanley, 1990; Johnson and Greening, 1999).

Furthermore, our corroboration of hypothesis H2 shows that if these directors perform their duties in companies located in countries with greater investor protection, they may have greater incentives to develop more complex ethical codes, as they will probably be more aware of how the company could improve its relationships with its shareholders and creditors. In addition, in institutional environments with weaker investor protection laws, it is likely that higher private benefits to insiders cause them to present greater opposition to the incorporation of corporate governance mechanisms to limit their discretionary powers.

Regarding the dummy variable representing environments characterized by high levels of investor protection, when their interaction with the number of independent directors is not considered, the impact is positive but not statistically significant. In the second model, the impact is positive, but the non-significance remains.

The proxy for the activity of the board, BOARDACT, has a significant positive effect from the econometric standpoint for the CElevel variable in the first model, for an estimated confidence level of 95%. Therefore, the greater the number of board meetings, the more likely the company is to implement a wide-ranging code of ethics. Its directors are likely to participate more actively and to have a more direct influence on the company strategy. This finding supports the claims of authors such as Lipton and Lorsch (1992), for whom active boards are more effective. In this sense, the frequency of their meetings allows them to supervise the management of the company better and demonstrates their greater interest in transparency and ethics.

The size of the board, expressed in linear terms, BOARDSIZE, presents a direct relationship with the dependent variable in all the equations considered. On the other hand, its square, BOARDSIZE2, is inversely related to the level of application of the ethical code, although this is not relevant from the econometric standpoint. The absence of a relationship in the latter respect shows that larger boards are more strongly committed to ethical issues. A possible explanation for this is that such a board will be guided by the experience and knowledge of all its members on ethical issues. In addition to a higher frequency of board meetings, directors will be more active and more likely to participate in decision making, especially regarding the content and level of application of the framework document for company ethics. Therefore, companies should take into account the importance of the size of the board, ensuring that it has sufficient members to control the management effectively and to secure ethical decisions (De Villiers et al., 2011).

Gender diversity (%FEM) has a positive impact, at the 99% confidence level, on the independent variable, CElevel. This finding is in accordance with the previous literature, which points out that female board members are more sensitive to ethical questions. They usually present a greater concern with compliance with regulations in such matters and in meeting the requirements of different stakeholders. Additionally, gender diversity is associated with greater experience and stricter compliance with the firm's legal and moral obligations (O’Neill et al., 1989). Thus, this finding suggests that companies wishing to achieve higher standards of ethical behaviour are more likely to succeed if they include a greater number of women on the board. These results are consistent with those of previous studies, such as García-Sánchez et al. (2008) and Rodríguez Domínguez et al. (2009).

With respect to the remaining control variables, firm size (FIRMSIZE) has a significant positive effect at the confidence level of 99%, in all the models analysed. The SECTOR variable has a significant negative effect at the confidence level of 95%. The control variables MTB and Leverage have a positive non-significant coefficient in the models considered. Thus, we conclude that larger companies can access more resources with which to address ethical issues. Furthermore, they present more extensive publication of their activities, in accordance with processes of legitimation (García-Sánchez et al., 2008).

Sensitivity analysisTo increase the robustness of the results presented in the previous section, three additional robustness analyses were carried out.

In the first such analysis, the dummy variable for investor protection was replaced with the original numerical values. In addition, a factor analysis was performed to group these values into a single component and to interact them with the percentage of independent directors.

The results of the factor analysis yielded a single factor that accounts for 75.48% of the variance of the four numerical variables selected to determine the level of investor protection. The anti-director rights index has a load factor of 0.947; the judicial efficiency index one of 0.890; the common-law country dummy one of 0.881; and the index of law and order one of 0.744.

Subsequently, we ran a regression in which this factor was included as a variable identifying the level of investor protection, as well as its interaction with the number of independent directors. The results are very similar to those obtained for the original model. Thus, the proportion of independent directors is significant at the confidence level of 99%, with a coefficient of 0.46. The interaction is also significant, at the same level of confidence, presenting a coefficient of 1.39. Taken together, these results show that the independent directors of companies located in countries with high levels of investor protection have a significant and positive effect on the implementation of an ethical code with a higher level of application (coef=0.46+1.39=1.85) compared with companies located in weaker legal environments (coef=0.46).

In the second robustness analysis, the original sample was divided into two blocks of countries. The first block comprised Germany, Norway, Denmark, Finland, France, and Sweden, and corresponded to companies included in the sample for the period 2007–2009. The remaining countries formed the second subsample, as data were available for the whole period, 2003–2009.

For the first block of countries, the variables %INDEP and %INDEP*DINV_PROTEC are significant at the confidence level of 99%. Once again, the independent directors of companies located in countries with high levels of investor protection have a positive and significant effect on the implementation of an ethical code with a higher level of application (coef=0.11+1.53=1.64) compared with companies located in weaker legal environments (coef=0.11). For the second block of countries and at the same level of confidence, the coefficients would be 0.16 and 0.65, respectively. Thus, the results obtained are similar.

Finally, in the third robustness analysis (Table 6), we defined a sample from the companies that have raised the level of application of their ethical code during the period analysed. These results show an impact of 0.41 for %INDEP and one of 1.28 for %INDEP*DINV_PROTEC.

Robust analysis for variations in the level of application of codes of ethics.

| CElevelit=β0+β1%INDEPit−1+β2%INDEP∗DINV_PROTECit−1+β3DINV_PROTECit+β4%FEMit+β5BOARDSIZEit+β6BOARDSIZE2it+β7BOARDACTit+β8FIRMSIZEit+β9Leverageit+β10MTBit+β11Sectorit+βinYear+μit+ηi | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Coef. | Std. Err. | VIF | Z | p>|z| |

| %INDEP | 0.41 | 0.09 | 2.50 | 4.53 | 0.000 |

| %INDEP*DINV_PROTEC | 1.28 | 0.24 | 2.35 | 5.32 | 0.000 |

| DINV_PROTEC | −0.57 | 0.18 | 2.03 | −3.11 | 0.002 |

| %FEM | 0.73 | 0.07 | 1.09 | 10.4 | 0.000 |

| BOARDSIZE | 0.17 | 0.05 | 4.27 | 3.19 | 0.001 |

| BOARDSIZE2 | −0.17 | 0.27 | 4.23 | −0.65 | 0.515 |

| BOARDACT | 0.94 | 0.07 | 1.02 | 13.01 | 0.000 |

| FIRMSIZE | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1.15 | 4.85 | 0.000 |

| Leverage | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −1.62 | 0.105 |

| MTB | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 0.20 | 0.842 |

| SECTOR | −0.08 | 0.03 | 1.02 | −2.35 | 0.019 |

| D2005 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 1.18 | −2.62 | 0.009 |

| D2006 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.21 | 1.50 | 0.134 |

| D2007 | 1.17 | 0.07 | 1.23 | 15.93 | 0.000 |

| D2008 | 1.12 | 0.07 | 1.24 | 15.24 | 0.000 |

| D2009 | 1.46 | 0.10 | 1.19 | 14.19 | 0.000 |

| _cut1 | −0.09 | 0.43 | −0.22 | 0.828 | |

| _cut2 | 0.74 | 0.43 | 1.72 | 0.085 | |

| _cut3 | 1.48 | 0.43 | 3.42 | 0.001 | |

| _cut4 | 3.10 | 0.43 | 7.21 | 0.000 | |

| rho | 0.70 | 0.02 | 40.14 | 0.000 | |

| Log-likelihood | −3803.70 | ||||

| Chi-squared | 564.42 | ||||

| p-value | 0.000 | ||||

“CElevel” is an ordinal variable, taking values from 0 to 4, according to the level of inclusion or application of the firm's code of ethics. “%INDEP” is the percentage of independent directors on the board. It interacts with the DINV_PROTEC variable to identify the role of independent directors in companies located in countries with above-average levels of investor protection. “%FEM” represents the percentage of women on the board of directors. “BOARDSIZE” is a numeric variable representing the total number of board members, internal and external. “BOARDSIZE2” is a numeric variable representing the square of the total number of board members, internal and external. “BOARDACT” is a numeric variable expressing the number of board meetings held each year. “FIRMSIZE” is the size of the corporation, measured by the logarithm of its total assets. “Leverage” is the level of corporate debt represented as the ratio external funds/equity. “MTB” represents the market value of the company compared to its book value. “SECTOR” is a numeric variable identifying the firm's sector of activity.

Statistically significant coefficients are shown in bold.

Recent corporate scandals and the financial crisis have led to growing concern about ethical issues and, in this respect, the influence of good governance practices. The negative effect of unethical business practices on firms’ reputations also affects the managers involved and, hence, the body responsible for supervising managers’ performance, i.e., the board of directors. This effect is particularly felt by the independent directors, because their professional capabilities are thus called into question. This can often result in the loss of employment opportunities in other companies and can even lead to the firm becoming immersed in illegal actions.

In order to avoid this damage to their reputation, these board members encourage the adoption of corporate codes of conduct, which may take the form of pragmatic mechanisms to be implemented when individuals prone to misconduct violate the trust placed in them (Stevens et al., 2005). These mechanisms would constitute systems and procedures aimed at generating confidence by jeopardizing discretionality and managerial opportunism. Moreover, they would boost market confidence because the existence of such a code of conduct would indicate that the firm behaves in accordance with the ethical and legal standards expected of it.

Ideally, these ethical guidelines would be more fully developed in business environments with weaker legal frameworks as regards investor protection, in order to provide alternative sources of protection for shareholders and creditors and to prevent managers from benefiting from discretionary decisions. However, the results obtained indicate that the involvement of independent directors in actions to foster ethical behaviour is heightened in institutional settings characterized by greater protection for investors. Therefore, our findings indicate that board independence leads to more complex ethics and that this relationship is stronger when the institutional context provides investors with stronger protection.

From a theoretical standpoint, there cannot be said to be any homogeneity of corporate governance mechanisms at the international level. Our study detected complementarity between the internal and the external mechanisms that prevent the illegal forms of behaviour that may occur in multinational companies. These results have interesting practical implications, suggesting that there is a need for regulatory bodies in countries with a less favourable institutional environment so that investors can participate more actively in the development of ethical commitments. These regulatory bodies would establish preventive mechanisms to restrain unethical practices and issue regulations to toughen the penalties for these actions.

The present study has various limitations, which will be addressed in future research by the authors. Thus, the sole ethical commitment assumed was that of the existence of a code of ethics and its level of application. Future research should analyse the existence of other documents and business procedures aimed at preventing unethical actions, such as money laundering and bribery.