In a financial economic scenario in which the corporate survival of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is more conditioned than ever by competitive performance, this paper aims to show that the strategic incorporation of socially responsible actions, more concerned and engaged with stakeholders, contributes to improve the competitiveness of these organizations. Thus, the existence of a direct or mediated relationship between the development of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices and competitive performance has been analyzed from a multi-stakeholder perspective. To accomplish this task, data were collected from a sample of 481 Spanish SMEs and the technique of partial least squares (PLS) was used. Outcomes show that the development of CSR practices contributes to increase the competitive performance both directly and indirectly, through the ability of these organizations to manage their stakeholders. This study, therefore, supports the social impact hypothesis and offers evidence about some intangibles such as the relational capacity mediate the causal effect between CSR and competitive performance.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Social Responsibility (SR) or any of its aspects are gaining great attention in the academic and professional fields. Companies are increasingly more aware and encouraged to integrate and participate in CSR issues (Mark-Herbert and Von Schantz, 2007). It has been pointed out as an essential concept that business managers should understand and manage. Firms of all types and sizes are called to become socially responsible, ecologically sustainable and economically competitive (Orlitzky et al., 2011). However, the real development that CSR has experienced in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is different than in large corporations.

In general, SMEs have certain characteristics that do interesting developing detailed and specific studies focused on them. This kind of organization usually shows particular strategies and structures, less formalized and more dependent on the disposition, participation, and ability to design strategies of the owners/managers, which complicate the development of CSR actions similar to large corporations’ practices. The lack of knowledge that SME managers usually have about CSR, the close relations with stakeholders (Fisher et al., 2009; Russo and Tencati, 2009) and the tendency to use informal communication mechanisms (Nielsen and Thomsen, 2009) have been identified as reasons for the incipient research conducted so far. At any rate, this state should not be interpreted as a lack of implementation of CSR practices because, as several empirical studies at the international and national level have supported, SMEs carry out more practices than they acknowledge and, thus, they promote. This phenomenon has been referred to in literature as “silent social responsibility” (Jenkins, 2004; Jamali et al., 2009).

Two groups of complementary reasons have been identified to explain the firm's engagement in CSR: on one hand, those of a normative perspective, concerned with the moral correctness of firms and their managers, and on the other, those arising from an instrumental perspective, more related to the traditional performance goals of profitability and business growth. From a strategic approach, most academics agree to prioritize the instrumental focus over the normative perspective; they usually state that those organizations that do not orientate their activities under a CSR philosophy in the short- or medium-term will be at a significant competitive disadvantage. In this regard, for example, different studies have pointed to the adoption of sustainable policies contributing advantages for the company (Porter and Kramer, 2002), either through increasing financial returns (Orlitzky et al., 2003; Miras et al., 2014) or through improving business reputation (Bear et al., 2010; Stanaland et al., 2011).

Aguinis and Glavas (2012) highlighted the gap that exists in the literature in regards to the relationship between CSR and business performance, and encouraged researchers to clarify some of the “mechanisms” that make this association possible. While the relationship between CSR and business performance measures has already been scrutinized in several works, most of them focused on large corporations. Despite it is difficult to suppose that conclusions can be directly extrapolated to the SMEs, at the moment, few studies have been carried out analysing the CSR-firm performance link in SMEs (e.g., Marín and Rubio, 2008; Niehm et al., 2008; Hammann et al., 2009; Sweeney, 2009; Torugsa et al., 2012; Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández, 2013, 2014a; Turyakira et al., 2014). Of these studies, only a few have tried to measure the CSR practices from a multi-stakeholder perspective (e.g. Hammann et al., 2009; Sweeney, 2009; Torugsa et al., 2012; Turyakira et al., 2014), even though none of them employed a measure of business performance based on the competitiveness that reflected the level of financial and non-financial results achieved in comparison with the most direct competitors. Thereby, none of the reviewed studies considered a performance measure based on the economical–financial position along with the market position regarding quality of products, innovation and customers’ satisfaction.

Given this considerations; being aware of the special implementation of CSR practices conducted by reduced dimension businesses; considering the resources limitations of this kind of organizations; and lastly, knowing the owners/managers’ confusion about real effects of sustainable behaviours, this investigation aims to clarify the relationship between CSR and competitive performance targeting in the specific context of SMEs (i.e., companies with up to 250 employees). Additionally, delving into the causal relation between the main variables under study and following Surroca et al. (2010) suggestion, this paper investigates whether a firm's capacity to manage stakeholders and achieve competitive advantages has a mediating role between the CSR and the competitive performance of SMEs. Besides, this paper tests the role of firm size as control variable, which impacts on CSR and competitive performance.

To accomplish these tasks, the paper first includes a review of some important theoretical background about the CSR-firm performance link, paying special attention to the SMEs field. The next section also includes the proposition of the hypotheses under analysis. Subsequently, “Methods” section describes the sample, the questionnaire and the statistical process. Finally, after presenting an analysis of results and a discussion of the main findings in “PLS Analysis and Results” and “Discussion” sections, respectively, some conclusions are drawn in the final section. The paper ends warning of some limitations and suggesting future lines of research.

CSR and firm performance linkInterest in finding any possible relationship between CSR and business performance5 emerged more than forty years ago. Most previous studies corroborate that efforts to carry out CSR practices improve firm performance (Beurden and Gössling, 2008). However, the first impression is a field of mixed evidence (Peloza, 2009). Barnett stated in 2007 (p.794) that, “after more than thirty years of research, we cannot clearly conclude whether a one-dollar investment in social initiatives returns more or less than one dollar in benefit to the shareholder.” While some studies show a positive relationship (Maron, 2006; Wu, 2006; Rodgers et al., 2013; Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández, 2014a), others older claim a negative influence (Boyle et al., 1997; Wright and Ferris, 1997); besides, further studies are not able to demonstrate the direction or the sign of the relationship (Barnett and Salomon, 2006).

Margolis and Walsh (2003) also warned of these discrepancies and the consequent confusion when they pointed out the need to understand the conditions under which a corporation's effects impact society before looking for any link between a firm's social and financial performance. Discovering a universal rate of return for CSR activities is virtually impossible; it is necessary to bet on a contingent perspective (Barnett, 2007). Therefore, the model we propose for the specific context of the SMEs not only looks at the direct link between CSR and firm performance, but also aims to clarify how the CSR efforts are rewarded by the different stakeholders.

The direct relationship between CSR and firm performancePreston and O’Bannon (1997) identify that the theoretical frameworks, in which this relationship is normally underpinned, have two basic differentiating characteristics: the positive, negative or neutral sign of the relationship and the causal sequence of dependent variables. Based on the hypotheses of these authors and on Waddock and Graves's article (1997), seven possible types of CSR-financial performance (FP) relationships could be identified. Of which, most of the empirical outcomes support the social impact hypothesis and lead to reject any negative relationship between CSR and business performance (Beurden and Gössling, 2008).

The underlying theory, which suggests that a higher level of CSR practices leads to a higher level of business performance, is the stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984). According to the stakeholder theory, the success of an organization depends on the organization's capacity to manage the relationships with its stakeholders. Management of relationships with key business stakeholders has become an essential tool for value generation (Hammann et al., 2009), making the stakeholder theory's interpretation a necessary step in understanding any possible relationship amongst CSR and firm performance (Perrini et al., 2011).

In the field of SMEs, most studies that have analyzed the CSR-performance link have only made suggestions about strategic CSR adoption and implementation, or have explained some theoretical implications in regards to translating the integration of a socially responsible behaviour in business strategy into an improved performance (Moore and Manring, 2009; Tomomi, 2010). Only a few authors have been concerned with providing empirical evidence to corroborate these theoretical implications (Niehm et al., 2008; Hammann et al., 2009; Torugsa et al., 2012; Battaglia et al., 2014; Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández, 2014a; Turyakira et al., 2014).

From the theoretical perspective of stakeholders, the owners/managers of SMEs are able to more easily express their values towards internal stakeholders and external stakeholders with whom they have a close relationship, than towards more abstract ones like society (Hammann et al., 2009). Despite how SMEs manage their reputation, these organizations are generally better positioned to take advantage of the potential benefits from CSR programmes (Sarbutts, 2003) because they maintain more close, honest and flexible relationships with most of their stakeholders (Russo and Tencati, 2009). The owners/managers able to establish the appropriate objectives and join efforts to accomplish a socially responsible behaviour will contribute to the short-term benefit and to the competitiveness and long-term business growth (Moore and Manring, 2009; Revell et al., 2010).

To achieve these competitive advantages, several authors make their own considerations. Tomomi (2010) noted, for example, that SMEs perceive environmental management as a possible way to provide opportunities for their business and likely cause competitive advantages. Aragón-Correa et al. (2005) highlighted that the commitment to environment and the implementation of measures for its protection can become an important source of competitive advantages for SMEs. On the other hand, Niehm et al. (2008) proved how a company's commitment to the community was directly associated with financial performance.

Under the instrumental approach of stakeholder theory, CSR should be incorporated into business planning by trying to develop business strategies that meet the approval of stakeholders (Parker, 2005). In this way, managers could try to maximize the benefits and value of their businesses while meeting the expectations of their stakeholders (Jensen, 2001). However, this maximization of value cannot be measured only from a financial perspective, but also from a broader approach. Marín and Rubio (2008), for instance, used a multidimensional measure of competitive success, made up of seven dimensions: market share, productivity, solvency, reputation, customer satisfaction, employee satisfaction and competitive position in terms of price, quality and innovation.

From an instrumental approach of stakeholder theory, Hammann et al. (2009) and Sweeney (2009) proposed to examine the relationship between CSR and firm performance considering that socially responsible management enabled companies to gain competitive advantages that add value. In both studies, a similar theoretical model is proposed which basically relates three variables: CSR, measured as the practices of socially responsible management towards different stakeholders; firm performance, as profit improvement; and a last variable which would bring together the potential and expected effects of suitable stakeholder management (improving employee satisfaction, reducing absenteeism, powering image, securing the loyalty of customers and employees, etc.). In both cases, the authors end up stating that CSR implementation improves firm performance through the impact that these practices have on the organization-stakeholder relationships.

In one of the latest studies, Torugsa et al. (2012) also found that the SMEs’ capability of managing stakeholders, along with the development of a proactive strategy and the knowledge to achieve a shared vision, are positively associated with a proactive CSR. In turn, their study shows how this proactive CSR causes an improvement in firm financial performance. Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2013), in a survey developed from Spanish micro-enterprises,6 verified that the positive predisposition of a firm's CEO has a direct impact on competitive success and that innovation positively mediates the relationship between these variables. Another recent study analysing the link between CSR and competitiveness performance has been conducted by Battaglia et al. (2014). Using data from Italian SMEs, which operate in the fashion industry, authors show a strong and positive correlation among several social performance indicators and two competitiveness dimensions: innovation and intangible performance.

Literature reviews and meta-analysis studies about the relationship under discussion have postulated the social impact hypothesis as the most frequent theoretical background in the study of CSR-firm performance link (Orlitzky et al., 2003; Beurden and Gössling, 2008; Aguinis and Glavas, 2012; Miras et al., 2014). In addition, the few studies identified in the context of SMEs leads us to reject any causal relationship that foresees companies will not be positively rewarded by their efforts in CSR. Therefore, since we hold that any relationship that arises between these variables must be made adopting the hypothesis of social impact, that is, expecting positive stakeholders’ reactions coming from increasingly socially responsible business behaviour (instrumental approach of stakeholder theory), the first hypothesis for testing in this paper as follows:H1 The development of CSR practices enables SMEs to improve their competitive performance.

From the stakeholder management approach, Jones (1995) stated that it is sensible to expect that CSR contributes to the creation of sustainable competitive advantages that improve business performance and encourage a positive relationship between the variables. Barnett (2007) asserted that the positive impact that CSR could have on business performance primarily would be due to the achievements arisen from an improved socially responsible behaviour and its effect on firm-stakeholder relationships. Marín et al. (2012) claimed that CSR efforts foster the emergence of positive stakeholders’ reactions to the company and that this does not only affect a firm's value in general, but it also improves the competitive positioning.

The concern for stakeholders and the communication with them for seeking to ensure a socially responsible behaviour allow firms to develop some particular intangible assets. On the basis of the establishment of relationships and interactions, firms are able to develop resources that will promote the development and maintenance of competitive advantages, which are hard to measure by means of accounting or physical parameters.

Investigation into company-stakeholder reciprocity was already proposed as a future research line by Perrini et al. (2011), who suggested that the usage of mediating variables that represent these interactions would contribute to increase knowledge about the mechanisms through which the CSR practices positively impact on business performance. Different authors have noted that the appearance of empirical discrepancies about the sign identified for the CSR-firm performance link might be due to the omission of certain confounding variables (McWilliams et al., 2006; Orlitzky, 2008). The search for a simple correlation between these variables might not be right because CSR could end up impacting on the income statement through intermediary variables. Thus, as Surroca et al. (2010) tested, the omission of some moderating and mediating variables would justify the lack of evidence to contrast that CSR and performance are significantly associated.

Because of the growing suggestions around the relevance of considering potential intermediary variables (Beurden and Gössling, 2008) and attending to competitive advantages that a firm can get from its interaction with stakeholders, an additional variable has been added into the model: relational improvements.

In agreement with the theoretical approach adopted, there should be positive reciprocity between the firm and stakeholders. Higher CSR efforts should result in higher rewards coming from stakeholders in the form of positive enterprise perceptions. Specifically, as a concept, this construct encompasses the set of business achievements or benefits coming from the manner in which an enterprise manages its relationships with key stakeholders. Through relational improvements variable, the importance of interaction with stakeholders is emphasized, with the relationship being the unit of analysis, which must be understood as the “farming” of strong interactions between two parties that keep any economic or social link and pursue mutual benefits.

Barney (1986) had already found that those organizations with a closer relationship with their stakeholders were able to achieve certain competitive advantages. At the organizational level, the capacity to manage stakeholders has been defined as “the ability to establish trust-based collaborative relationships with a wide variety of stakeholders, especially those with non-economic goals” (Sharma and Vredenburg, 1998, p.735). Since this ability can be considered, from a CSR approach, to improve competitive performance, our model tries to pinpoint the causal effect that the implementation of sustainable management has on performance and how it disrupts the direct CSR-firm performance relationship.

Relational improvements, therefore, could be viewed simultaneously as both an effect and a cause, depending on whether the attention is focused on the impact that CSR practices have on the relationship with stakeholders or on how business performance can be explained based on the positive reaction of stakeholders. To confirm any mediating effect that this variable could play, the following hypothesis has been proposed:H2 In SMEs, the relational improvements have a positive mediating effect on the relationship between developed CSR practices and competitive performance.

At last, along with direct and mediating effects proposed, firm size has been considered as a control variable7. Several previous studies have contrasted that size has a significant impact on the association between CSR and business performance (Bansal, 2005; Beurden and Gössling, 2008), even when the sample only consists of SMEs (Sweeney, 2009; Torugsa et al., 2012).

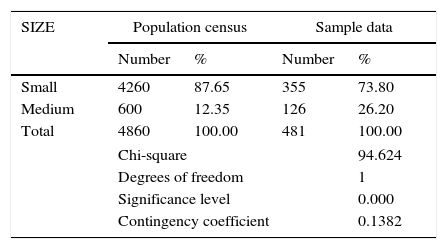

MethodsSample and dataThe random selection of SMEs was done based on companies from Spain listed in the SABI database. The initial sample was 552 companies located in the Murcia region, in southeast Spain. However, during the filtering process, wrongly answered questionnaires, questionnaires completed by companies with fewer than 10 employees (micro-enterprises) or questionnaires from organizations with a special legal form, such as cooperative societies, demanding different treatment were eliminated. Besides, after collecting data, a group of three experts examined all the responses, looking for senseless answers. Finally, the sample comprised 481 SMEs (Table 1).

The data collection process was carried out directly by CSA Consultants Company8, which was responsible for contacting each of the selected SMEs from December 2010 to February 2011. The information about the variables used for the study was collected through a questionnaire addressed to the companies’ managers or the person in charge of the social responsibility issues and it took, on average, approximately 20minutes to complete. This questionnaire was previously validated through a pilot survey, after which some of the questions were modified and reworded in order to ensure the correct understanding and answer by interviewees, irrespective of the size of their firms9. Most questions were measured through a five-point Likert scale, since it has been widely used in surveys conducted about CSR in SMEs (Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández, 2014b).

To assess non-response bias, Pearson chi-square test and Contingency Coefficient were used to compare the business size of respondent and non-respondent firms, and to evaluate if there was any significant difference. No significant differences were found and it can be concluded, therefore, that, based on size, there is no difference between firms that respond and those that did not.

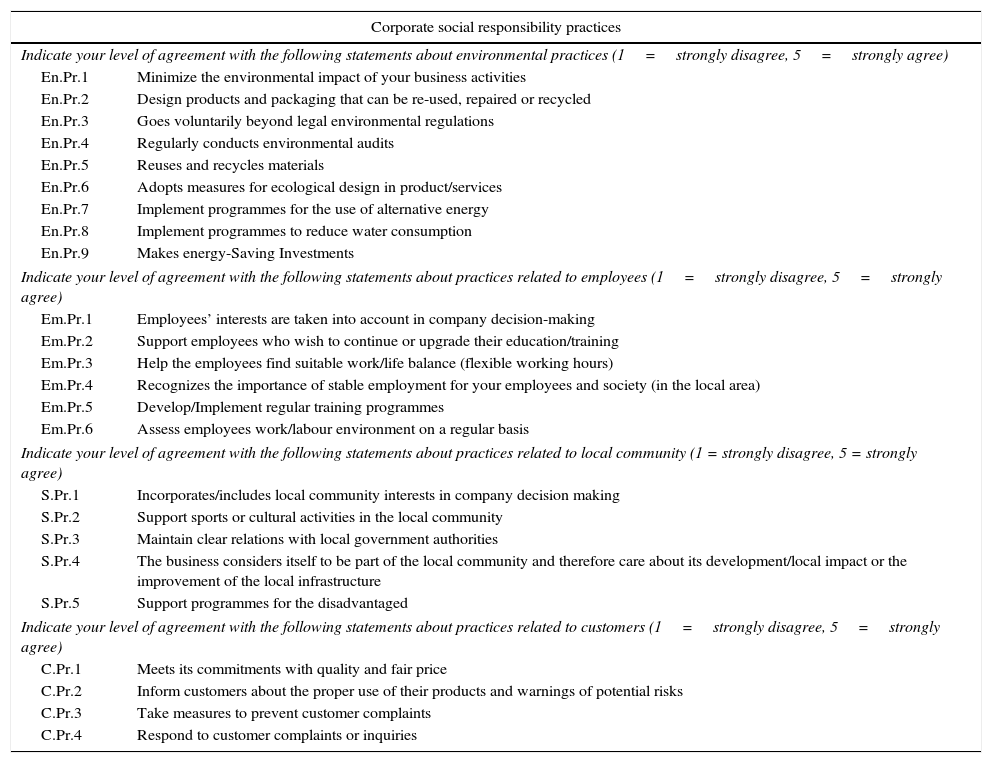

MeasuresCSR practices (CSR)Since the social impact hypothesis arises from the CSR multi-stakeholder perspective, we have considered a CSR measure which gathers items grouped around four key stakeholders (Turker, 2009; Battaglia et al., 2014; Turyakira et al., 2014): environment, employees, society and customers. Specifically, the scale of Lechuga (2012) was chosen as an instrument for measuring the CSR. The author developed and validated a measuring instrument according to the psychometric theory of scales validation. In her study, 57 CSR practices were grouped into six stakeholder categories (employees, customers, suppliers, environment, local community and corporate governance). The author designed and validated a final scale composed of 24 items, grouped into four key stakeholder categories (environment, employees, customers and local community), as specified in Table 2.

‘CSR practices in SMEs’ scale.

| Corporate social responsibility practices | |

|---|---|

| Indicate your level of agreement with the following statements about environmental practices (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree) | |

| En.Pr.1 | Minimize the environmental impact of your business activities |

| En.Pr.2 | Design products and packaging that can be re-used, repaired or recycled |

| En.Pr.3 | Goes voluntarily beyond legal environmental regulations |

| En.Pr.4 | Regularly conducts environmental audits |

| En.Pr.5 | Reuses and recycles materials |

| En.Pr.6 | Adopts measures for ecological design in product/services |

| En.Pr.7 | Implement programmes for the use of alternative energy |

| En.Pr.8 | Implement programmes to reduce water consumption |

| En.Pr.9 | Makes energy-Saving Investments |

| Indicate your level of agreement with the following statements about practices related to employees (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree) | |

| Em.Pr.1 | Employees’ interests are taken into account in company decision-making |

| Em.Pr.2 | Support employees who wish to continue or upgrade their education/training |

| Em.Pr.3 | Help the employees find suitable work/life balance (flexible working hours) |

| Em.Pr.4 | Recognizes the importance of stable employment for your employees and society (in the local area) |

| Em.Pr.5 | Develop/Implement regular training programmes |

| Em.Pr.6 | Assess employees work/labour environment on a regular basis |

| Indicate your level of agreement with the following statements about practices related to local community (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) | |

| S.Pr.1 | Incorporates/includes local community interests in company decision making |

| S.Pr.2 | Support sports or cultural activities in the local community |

| S.Pr.3 | Maintain clear relations with local government authorities |

| S.Pr.4 | The business considers itself to be part of the local community and therefore care about its development/local impact or the improvement of the local infrastructure |

| S.Pr.5 | Support programmes for the disadvantaged |

| Indicate your level of agreement with the following statements about practices related to customers (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree) | |

| C.Pr.1 | Meets its commitments with quality and fair price |

| C.Pr.2 | Inform customers about the proper use of their products and warnings of potential risks |

| C.Pr.3 | Take measures to prevent customer complaints |

| C.Pr.4 | Respond to customer complaints or inquiries |

In addition to being one of the few alternatives to assess the level of CSR practices in the field of SMEs, it should be noted the structural similarities among this and the scales that other authors have proposed under the stakeholder approach, regardless of organizational size (Turker, 2009; Mishra and Suar, 2010; Turyakira et al., 2014). The validity of each one of the indicators used can be also corroborated according to other CSR measures developed from different approaches, such as the triple bottom line perspective (Torugsa et al., 2012; Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández, 2014a).

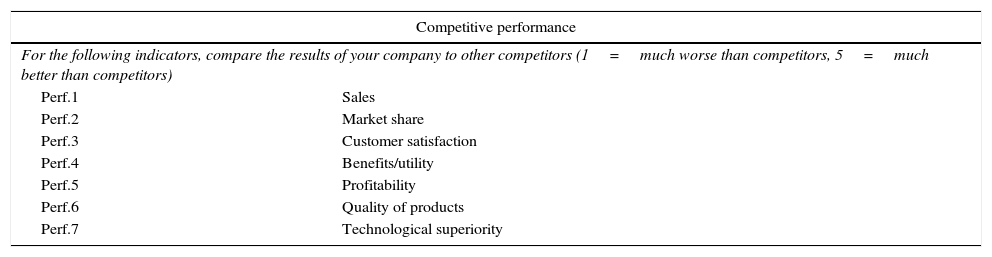

Competitive performance (C.PERF.)For assessing firm performance, we have opted for an approach similar to the one adopted by Marín et al. (2012) or Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2013), using a variable more focused on assessing competitive performance than on financial performance data. Consequently, the competitiveness has been taken from a two-dimensional perspective, using subjective information about some financial measures on the one hand, and some commercial and technological differentiation items on the other. Thus, after conducting a review of prior studies focused on SMEs in which any measure of competitiveness was used, we designed an initial scale made up of seven items (Table 3). Of these, four were more associated with financial economic performance and three with competitive differentiation.

Items of the questionnaire to measure Competitive Performance and Relational Improvements.

| Competitive performance | |

|---|---|

| For the following indicators, compare the results of your company to other competitors (1=much worse than competitors, 5=much better than competitors) | |

| Perf.1 | Sales |

| Perf.2 | Market share |

| Perf.3 | Customer satisfaction |

| Perf.4 | Benefits/utility |

| Perf.5 | Profitability |

| Perf.6 | Quality of products |

| Perf.7 | Technological superiority |

| Relational improvements | |

|---|---|

| Despite the context of general crisis in the past three years, there have been improvements relating to… (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree) | |

| Imp.1 | Service to customers |

| Imp.2 | Relations with customers |

| Imp.3 | Customer loyalty |

| Imp.4 | The firm image |

| Imp.5 | Relations with suppliers |

| Imp.6 | The cost reduction in supplies |

| Imp.7 | The cost reduction in logistic and inventory |

| Imp.8 | The employee satisfaction |

| Imp.9 | Absenteeism |

| Imp.10 | Work environment |

| Imp.11 | The loyalty and morale of employees |

| Imp.12 | The owners and investors satisfaction |

| Imp.13 | Relations with owners |

| Imp.14 | The owners’ knowledge about the progress of the firm |

| Imp.15 | Relations with its local community and environment |

Before performing an analysis of the dimensionality of the construct, a global internal consistency test for the seven issues considered as indicators of competitive performance was carried out. Additionally, we contrasted that the elimination of no variable improved the internal consistency of the scale, which reinforces the assumption that these seven indicators were related and they measure an underlying concept. Table 4 shows the results from factor analysis.

Factor analysis and refinement of competitive performance scale rotated components (N=481).

| Items | Communality | F.1 | F.2 | Corr. item-total factor corrected | α of subscale if item is eliminated from its factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perf.1 | 0.653 | 0.762 | 0.269 | 0.682 | 0.818 |

| Perf.2 | 0.565 | 0.706 | 0.259 | 0.609 | 0.848 |

| Perf.3 | 0.666 | 0.267 | 0.771 | 0.585 | 0.588 |

| Perf.4 | 0.802 | 0.887 | 0.123 | 0.753 | 0.787 |

| Perf.5 | 0.786 | 0.880 | 0.107 | 0.735 | 0.795 |

| Perf.6 | 0.778 | 0.116 | 0.875 | 0.667 | 0.682 |

| Perf.7 | 0.607 | 0.167 | 0.761 | 0.525 | 0.757 |

| Variance explained | 50.07% | 19.33% | |||

| Total variance explained | 69.40% | ||||

| α of subscale | 0.853 | 0.758 | |||

| α of refined subscale | 0.853 | 0.758 | |||

Bold and shaded values represent the highest loading of each item on the dimensions (factors) identified for the competitive performance scale.

The factorial analysis results show how the two dimensions proposed gather indicators which aim to measure a similar concept. One of them collects items about the economic and financial performance compared with competitors, and the other gathers items about the competitive differentiation. Moreover, to corroborate the homogeneity of the questions within each dimension, it was verified that the correlation between each item and its subscale was greater than 0.5 and that the Cronbach's alpha value did not increase after removing it. As can be appreciated in Table 4, no item has been eliminated after the refining process.

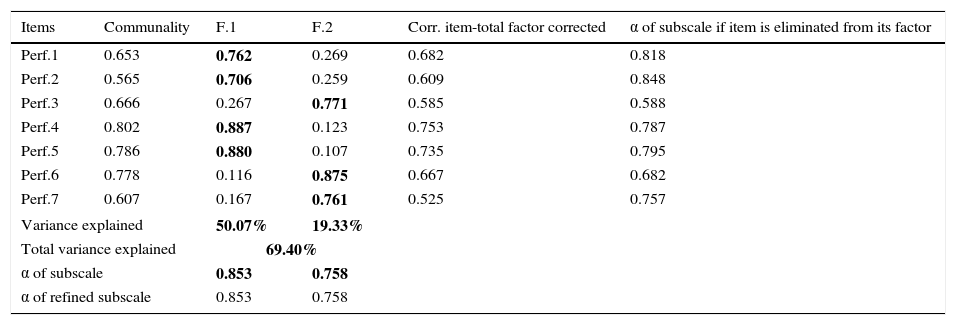

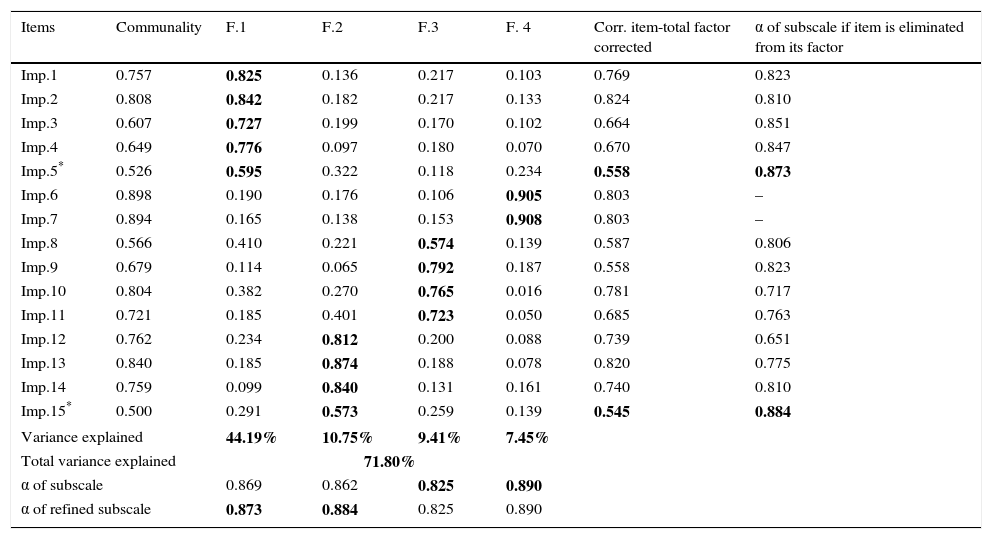

Relational improvements (R.IMP.)For this mediating variable, a multidimensional construct has been designed from a multi-stakeholder organizational management perspective, identifying as first-order dimensions the advantages from managing their relationship with each stakeholder identified for this kind of organization: customers, employees, suppliers, owners and local community. As with the competitive performance construct, we performed a global internal consistency test of the fifteen items (see Table 4) considered initially to measure this construct and selected from a literature review. Table 5 shows the results from factorial analysis of the scale proposed to measure the relational improvements construct.

Factor analysis and refinement of relational improvements scale rotated components (N=481).

| Items | Communality | F.1 | F.2 | F.3 | F. 4 | Corr. item-total factor corrected | α of subscale if item is eliminated from its factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imp.1 | 0.757 | 0.825 | 0.136 | 0.217 | 0.103 | 0.769 | 0.823 |

| Imp.2 | 0.808 | 0.842 | 0.182 | 0.217 | 0.133 | 0.824 | 0.810 |

| Imp.3 | 0.607 | 0.727 | 0.199 | 0.170 | 0.102 | 0.664 | 0.851 |

| Imp.4 | 0.649 | 0.776 | 0.097 | 0.180 | 0.070 | 0.670 | 0.847 |

| Imp.5* | 0.526 | 0.595 | 0.322 | 0.118 | 0.234 | 0.558 | 0.873 |

| Imp.6 | 0.898 | 0.190 | 0.176 | 0.106 | 0.905 | 0.803 | – |

| Imp.7 | 0.894 | 0.165 | 0.138 | 0.153 | 0.908 | 0.803 | – |

| Imp.8 | 0.566 | 0.410 | 0.221 | 0.574 | 0.139 | 0.587 | 0.806 |

| Imp.9 | 0.679 | 0.114 | 0.065 | 0.792 | 0.187 | 0.558 | 0.823 |

| Imp.10 | 0.804 | 0.382 | 0.270 | 0.765 | 0.016 | 0.781 | 0.717 |

| Imp.11 | 0.721 | 0.185 | 0.401 | 0.723 | 0.050 | 0.685 | 0.763 |

| Imp.12 | 0.762 | 0.234 | 0.812 | 0.200 | 0.088 | 0.739 | 0.651 |

| Imp.13 | 0.840 | 0.185 | 0.874 | 0.188 | 0.078 | 0.820 | 0.775 |

| Imp.14 | 0.759 | 0.099 | 0.840 | 0.131 | 0.161 | 0.740 | 0.810 |

| Imp.15* | 0.500 | 0.291 | 0.573 | 0.259 | 0.139 | 0.545 | 0.884 |

| Variance explained | 44.19% | 10.75% | 9.41% | 7.45% | |||

| Total variance explained | 71.80% | ||||||

| α of subscale | 0.869 | 0.862 | 0.825 | 0.890 | |||

| α of refined subscale | 0.873 | 0.884 | 0.825 | 0.890 | |||

Bold and shaded values represent the highest loading of each item on the dimensions (factors) identified for the relational improvements scale.

From this initial analysis, it can be identified that, in most cases, the dimensions group homogeneous elements, with the exception of items Imp.5 (Improvements relating to firm-suppliers relationships) and Imp.15 (Improvements relating to firm-local community relationships). Although these indicators no have low loadings, it is true that their values are considerably lower than other indicators’ loadings. Furthermore, their inclusion in Factor 1 (related to customers) and Factor 2 (related to owners/investors) lacks any theoretical support. Like with the competitive performance, the homogeneity and consistency within each dimension were also checked. As Table 5 shows, the items Imp.5 and Imp.15 have not been measured reliably and disrupt slightly the internal consistency of their respective subscales. This leads us to definitely remove both items and consider that SMEs’ managers do not perceive or have difficulties appreciating any improvement related to suppliers and community relationships. In this way, the final scale obtained for relational improvements is composed of 13 variables, grouped in four dimensions, as the result of their relationship with customers, suppliers, employees or owners/investors.

SizeThe control variable was measured using, as manifest variables, the natural logarithm of total assets and the natural logarithm of number of employees, both measures taken from 2010. Simultaneously or individually, both measures have often been used in previous empirical studies about CSR and performance (Sweeney, 2009; Blanco et al., 2013).

MethodologyThe main methodology used has been the Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). The structural equation analysis has the advantage of analysing the definition of the latent constructs in the context of a group of causal effects. SEM brings together the contributions of econometrics referring to the prediction, along with the psychometric approach, related to the measurement of latent or unobserved variables inferred from indicators or manifest variables (Chin, 1998). There are two different statistical techniques for the SEM: methods based on covariance analysis and methods based on variance analysis.

In this case, we carried out the analysis using a variance-based SEM technique: Partial Least Squares (PLS). We have used this technique, instead of covariance-based models, because it is more suitable for the implementation of predictive studies, which explore complex problems and where previous theoretical background is scarce (Hulland et al., 2010). Moreover, only the PLS technique allows modelling variables of a formative nature (Polites et al., 2012). This technique has been previously used in similar studies (López-Gamero et al., 2008; Blanco et al., 2013; Gallardo-Vázquez et al., 2013; Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández, 2014b), due to its potential to describe relatively new phenomena from theoretical models and measures without a thorough theoretical background (Chin, 1998).

Before running SEM, the explanatory factorial analysis technique was carried out to second-order variables not validated previously in the literature, with the intention of identifying possible clusters of variables with common meaning. Thus, in addition to choosing contrasted questions from the literature to measure the relational improvements and competitive performance variables, it was necessary to check the reliability of the scales with the data extracted from the sample.

PLS analysis and resultsThe structural equation analysis has the advantage of analysing the definition of the latent variables in the context of a set of causal relationships. To do this, following the recommendations of some previous authors, such as Barclay et al. (1995), the contrasts should be interpreted distinguishing between the measurement and structural models, applying in each of them the suitable statistical parameters to assess them.

Since the main objective of this paper is the hypothesis contrast between second-order constructs (CSR, R.IMP. and C.PERF.) and a control variable, we are only going to put forward the analysis of the second-order model, having previously checked the validity of the measurement model of first-order according to the two-stage approach (Wright et al., 2012).

On the other hand, according to previous recommendations in the literature, the evaluation of the measurement model was performed as many times as models were considered to contrast each hypothesis. However, as significant differences were not found, we only present the results for the evaluation of the measurement model corresponding to the full model.

Before looking at the results of the estimations performed with the programme PLS-Graph 3.00, an assumption conditioning the analysis of the results should be explained: the CSR and R.IMP. constructs have been considered as second-order formative constructs. In both cases, we understand that the dimensions of these constructs capture heterogeneous aspects and that, therefore, they should be added to develop a measure of performed CSR practices in the first case, and a measure of achieved relational improvements in the second.

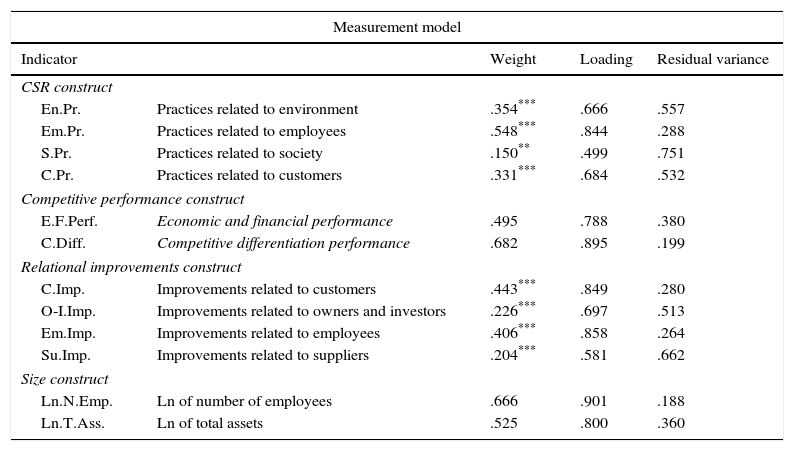

Measurement validationThe evaluation of the measurement model presented in Table 6 corresponds to the full model proposed. It is, therefore, a model containing both formative (CSR and R.IMP.) and reflective variables (C.PERF. and SIZE).

Measurement validation.

| Measurement model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Weight | Loading | Residual variance | |

| CSR construct | ||||

| En.Pr. | Practices related to environment | .354*** | .666 | .557 |

| Em.Pr. | Practices related to employees | .548*** | .844 | .288 |

| S.Pr. | Practices related to society | .150** | .499 | .751 |

| C.Pr. | Practices related to customers | .331*** | .684 | .532 |

| Competitive performance construct | ||||

| E.F.Perf. | Economic and financial performance | .495 | .788 | .380 |

| C.Diff. | Competitive differentiation performance | .682 | .895 | .199 |

| Relational improvements construct | ||||

| C.Imp. | Improvements related to customers | .443*** | .849 | .280 |

| O-I.Imp. | Improvements related to owners and investors | .226*** | .697 | .513 |

| Em.Imp. | Improvements related to employees | .406*** | .858 | .264 |

| Su.Imp. | Improvements related to suppliers | .204*** | .581 | .662 |

| Size construct | ||||

| Ln.N.Emp. | Ln of number of employees | .666 | .901 | .188 |

| Ln.T.Ass. | Ln of total assets | .525 | .800 | .360 |

| Validation of the formative constructs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicators | Original sample estimate | Variance Inflation Factor | Resampling bootstrap | ||

| Mean of subsamples (standard error) | T-statistic | ||||

| CSR | En.Pr. | .354*** | 1.214 | .355 (.062) | 5.740 |

| Em.Pr. | .548*** | 1.358 | .547 (.063) | 8.717 | |

| S.Pr. | .150** | 1.199 | .146 (.076) | 1.980 | |

| C.Pr. | .331*** | 1.261 | .326 (.070) | 4.674 | |

| R.IMP. | C.Imp. | .443*** | 1.607 | .450 (.081) | 5.464 |

| O-I.Imp. | .226*** | 1.478 | .230 (.072) | 3.084 | |

| Em.Imp. | .406*** | 1.819 | .396 (.078) | 5.190 | |

| Su.Imp. | .204*** | 1.222 | .198 (.068) | 3.012 | |

| Validation of the reflective constructs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal consistency reliability. Composite Reliability (ρc) | Convergent validity (AVE) | Discriminant validity AVE1/2 > correlations with… | |||||

| AVE1/2 | CSR | C.PERF. | R.IMP. | SIZE | |||

| C.PERF. | .830 | .710 | .843 | .450 | 1 | .477 | .218 |

| SIZE | .841 | .726 | .852 | .184 | .218 | .107 | 1 |

*Significant at p<0.10.

The most representative parameters, when working with formative character indicators, are the relative weights of each of these on the latent variable (Barclay et al., 1995). Because of this nature, typical of formative constructs, their validity cannot be evaluated using the same criteria as in the reflective models; that is, it cannot be assessed according to whether there is convergent and discriminant validity. Bollen (1989) proposes, instead, to study the formative construct validity by looking at the intensity and statistical significance of the weights of each item, as they give information about the relevance that these measures have on the structural model and on the determination of the latent construct they relate to.

Since, for the case of second-order formative constructs, the weights of the first-order constructs (dimensions) represent causal relationships between these and the former, the weights’ statistical significance was analyzed with the same procedure used for evaluating relationships between constructs: the resampling technique of Bootstrap, with which we have generated 5.000 alternative samples from the original data matrix. For each one of these subsamples, PLS re-estimates the parameters and then analyses the consistency of the results and determines if the coefficients obtained provide valid measures of population parameters. The accuracy of these estimates is contrasted using the T test statistic, with n−1 degrees of freedom, designed to test the null hypothesis that the estimated parameters from the population are not significantly different from those obtained in the sub-samples.

The results gathered in Table 6 allow us to see that formative constructs incorporated into the models (CSR and R.IMP.) are well-captured by their first-order dimensions: most with weights over 0.2 and significant at the 0.01 level. From an individual analysis of the weights, it is necessary to highlight that, in the case of the CSR construct, the highest weight belongs to practices related to employees. In contrast, the dimension capturing the practices related to society has the lowest weight. With respect to the R.IMP. construct, the relational improvements coming from customers and employees have a weight above the others.

Considering the scales “CSR Practices” and “Relational Improvements” as formative variables requires us to analyze the absence of multicollinearity. According to Diamantopoulos and Siguaw (2006), values for Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) over 3.3 suggest the existence of a high multicollinearity.

Furthermore, the data presented in Table 6 confirm the existence of competitive performance and size as reflective constructs consistently measured. In accordance with Carmines and Zeller (1994), the indicators have loadings exceeding 0.707, the composite reliability coefficients (ρc) are higher than 0.7 (internal consistency reliability), the average variance extracted values (AVE) exceed 0.5 (convergent validity), and the correlations with any other variable are smaller than the square root of their AVE values (discriminant validity).

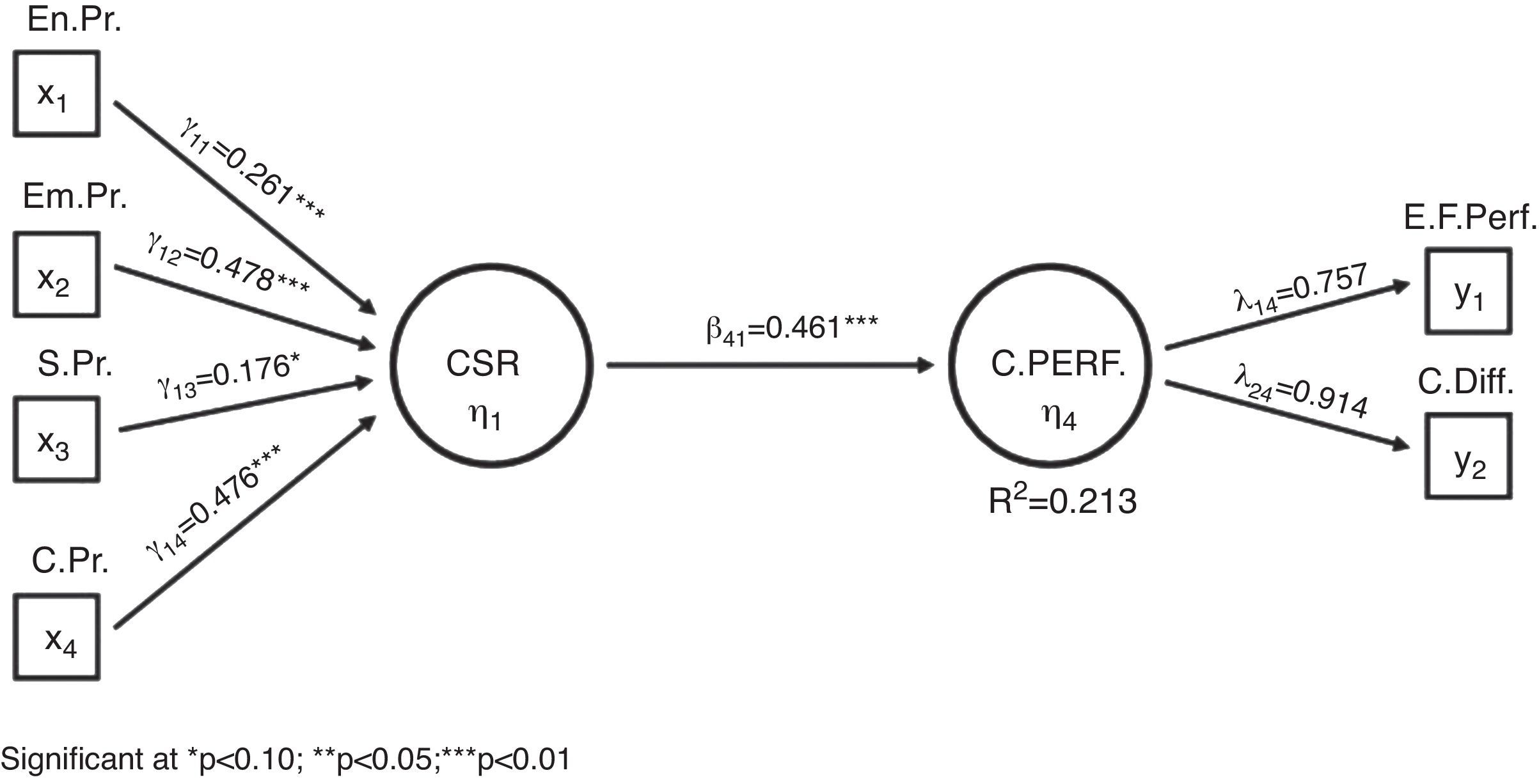

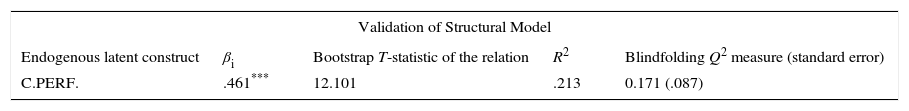

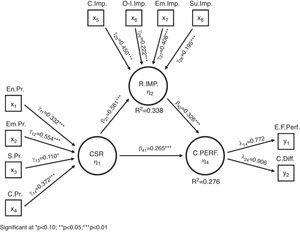

Structural validationThe main causal relationship under contrast, where a latent formative variable (CSR) determines a reflective (C.PERF.), represents a specific model known as “redundancy model” (Chin, 1998) (Fig. 1).

The assessment of the structural model supports the first hypothesized causal theoretical relationship and, therefore, CSR practices enable SMEs to improve their competitive performance. Attending to the results shown in Table 7, the development of CSR practices has a positive and significant effect on competitive performance (β41=0.461; significance=0.01). In addition, it can be argued that the development of CSR practices can predict or explain 21.3% of the competitive performance variance, surpassing the minimum 10% value recommended (Falk and Miller, 1992). The positive value observed for Q2 indicates that predictive capability of the theoretical model proposed for the contrast of H1 is adequate.

Analysis of the direct effect of the csr practices on competitive performance (Validation of Structural Model).

| Validation of Structural Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous latent construct | βi | Bootstrap T-statistic of the relation | R2 | Blindfolding Q2 measure (standard error) |

| C.PERF. | .461*** | 12.101 | .213 | 0.171 (.087) |

*Significant at p<0.10.

**Significant at p<0.05.

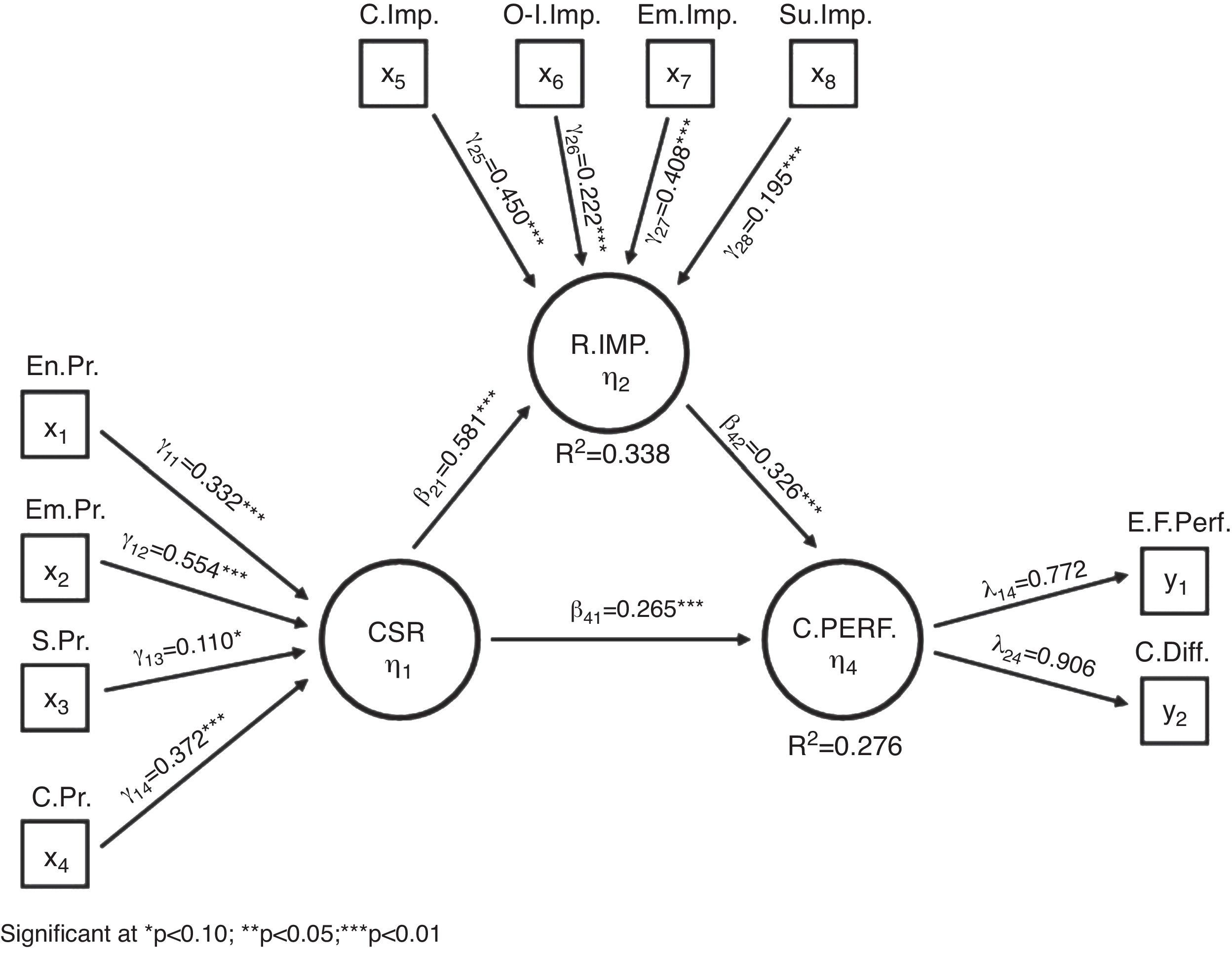

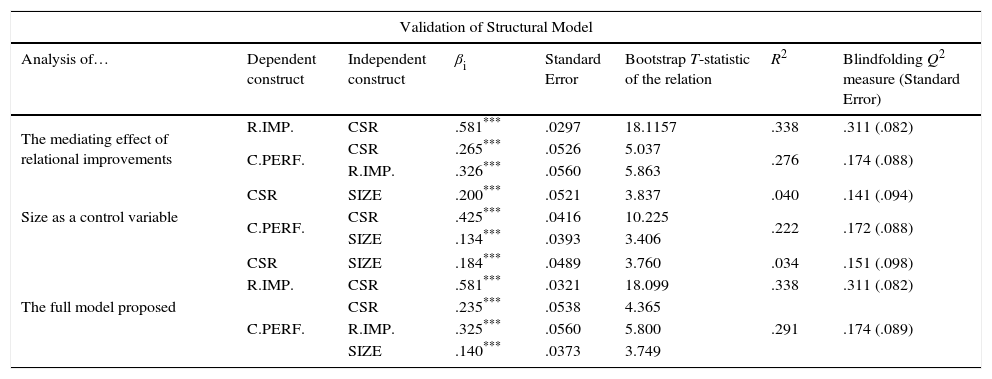

Having tested the first hypothesis, the isolated mediating effect of the relational improvements has been analyzed (Fig. 2).

Again, three indices are examined to evaluate the structural model. First, the relevance measures (Q2) show that, as before, the predictive capacity is adequate (Table 8). The path coefficients of the relations are higher than the minimum value of 0.2 required, and all are significant at 99%. Despite this, there has been a significant decrease in the coefficient path of the relationship between the constructs C.PERF. and CSR, diminishing from 0.461 to 0.265. This decrease was due to the incorporation of the construct R.IMP. as a mediating variable. To test this effect, Baron and Kenny (1986) set the following conditions:

- 1.

The partial mediation model should explain more variance of the main dependent variable (C.PERF.) than the model without mediation (R2 before=0.213, R2 now=0.276).

- 2.

There is a significant relationship between the independent variable initially considered (CSR) and the mediating variable (β21=0.581; significance=0.01).

- 3.

There is also a significant link between the mediating variable and the variable initially considered as dependent (β42=0.326; significance=0.01).

- 4.

Additionally, there must be a significant relationship between the constructs proposed in the direct model (RSE and C.PERF.), although this relationship should have quite slowed down as a result of the inclusion of a mediating variable (β41 before=0.461, β41 now=0.265).

Analysis of the mediating effect of relational improvements (Validation of Structural Model).

| Validation of Structural Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis of… | Dependent construct | Independent construct | βi | Standard Error | Bootstrap T-statistic of the relation | R2 | Blindfolding Q2 measure (Standard Error) |

| The mediating effect of relational improvements | R.IMP. | CSR | .581*** | .0297 | 18.1157 | .338 | .311 (.082) |

| C.PERF. | CSR | .265*** | .0526 | 5.037 | .276 | .174 (.088) | |

| R.IMP. | .326*** | .0560 | 5.863 | ||||

| Size as a control variable | CSR | SIZE | .200*** | .0521 | 3.837 | .040 | .141 (.094) |

| C.PERF. | CSR | .425*** | .0416 | 10.225 | .222 | .172 (.088) | |

| SIZE | .134*** | .0393 | 3.406 | ||||

| The full model proposed | CSR | SIZE | .184*** | .0489 | 3.760 | .034 | .151 (.098) |

| R.IMP. | CSR | .581*** | .0321 | 18.099 | .338 | .311 (.082) | |

| C.PERF. | CSR | .235*** | .0538 | 4.365 | .291 | .174 (.089) | |

| R.IMP. | .325*** | .0560 | 5.800 | ||||

| SIZE | .140*** | .0373 | 3.749 | ||||

*Significant at p<0.10.

**Significant at p<0.05.

Finally, Chin (1998) suggests a possible measure with which to analyze the mediating effect attending to the variation in the explained variance after the inclusion of a mediating variable in the model:

where Rincluded2: variance explained if the mediating variable is introduced; Rexcluded2: variance explained if it is not incorporated in the model.From data shown in Tables 7 and 8, the f2 estimated is 0.087, higher than the minimum limit of 0.02, which is considered to state that any variable incorporated into a model contributes to increase the explained variance significantly. Therefore, the second hypothesis is supported and it can be stated that relational improvements have a positive mediating effect on the relationship between developed CSR practices and competitive performance.

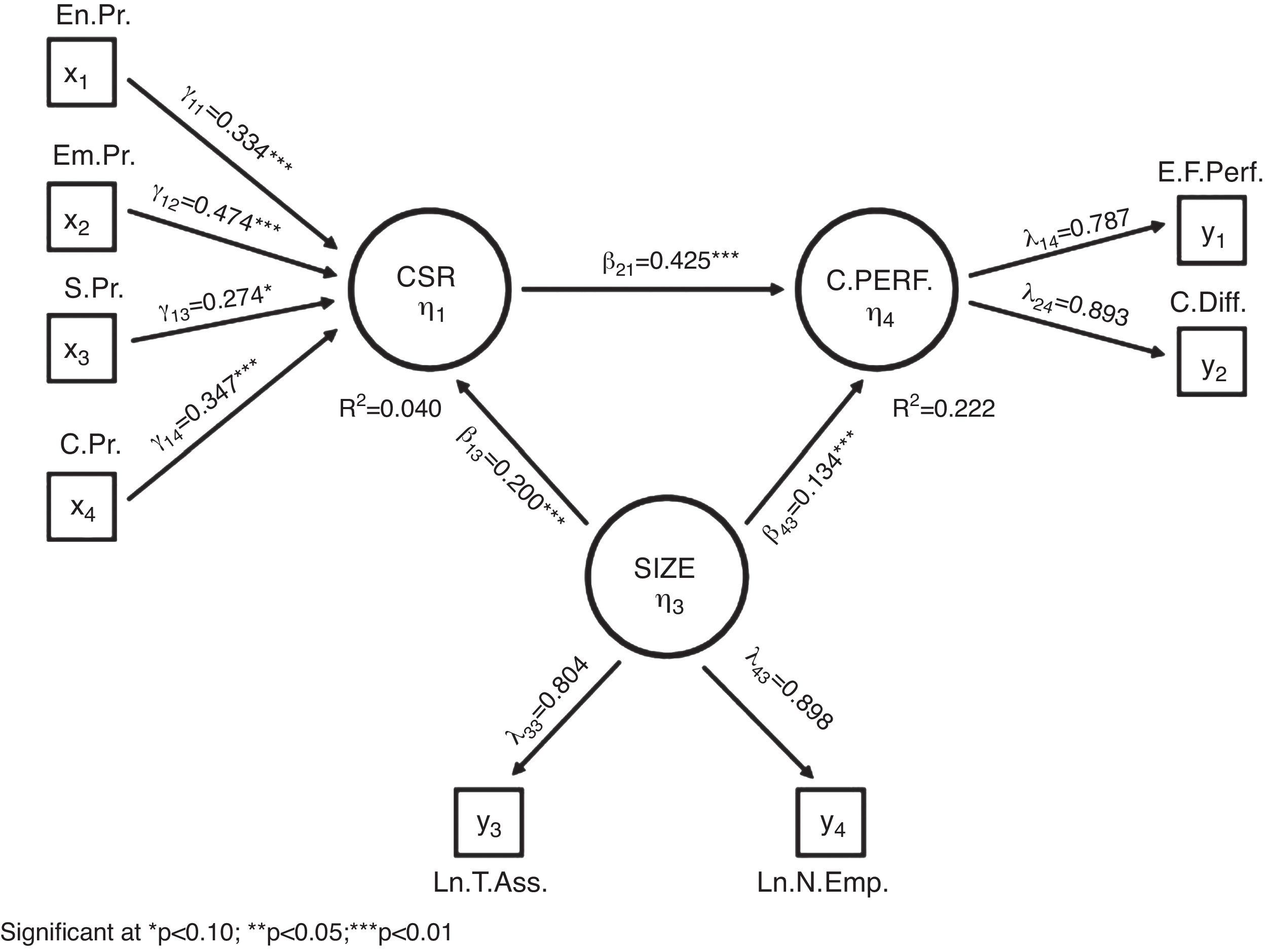

Additionally, the role of size as a control variable was checked. As it can be appreciated in Fig. 3, all estimated path coefficients are significant at 99% and there is a greater effect of the control variable on the development of CSR practices than on competitive performance.

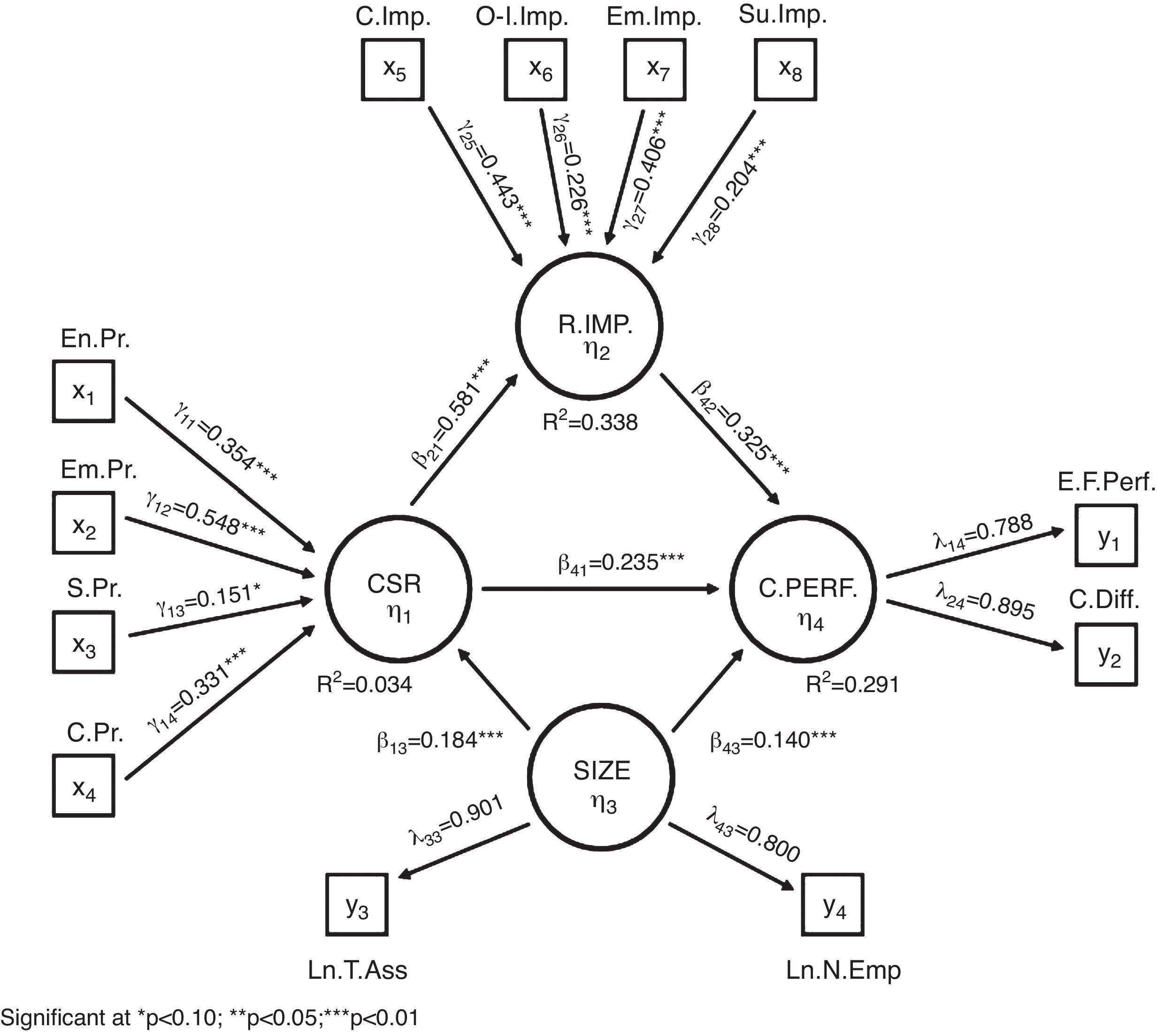

According to the results, it can be stated that size, incorporated as an exogenous variable in the model, has a very slight effect on CSR practices and competitive performance. It does not have a decisive incidence on the main relation under study. In any case, through a model assembling firm size along with the mediating effect under study, causal relationships amongst constructs were re-examined in a last analysis (Fig. 4).

From the results, first it is necessary to point out that all hypothesized paths are significant at the 0.01 level. The final proposed model explains or contributes to predict 29.1% of the competitive performance variance. Likewise, in agreement with Godos-Díez et al. (2014), two additional and complementary tests were applied to confirm the mediating effect in this full and final model. First, the Sobel Z test (1982) was performed to corroborate that this indirect effect was statistically significant (Z=5.526; p<0.001). Secondly, the procedure described by Preacher and Hayes in 2008 to test mediation effects was followed. According to these authors and after applying bootstrapping technique, it can be stated that R.IMP. partially mediates the relationship between CSR and C.PERF. and that the indirect impact of CSR on C.PERF. has an intensity of 0.189 and is significant, since 0 is not included in its estimated confidence interval of standardized regression (percentile bootstrap at 95%: 0.1327–0.2721).

DiscussionThe model finally proposed corroborates that the social impact hypothesis has sufficient empirical support and that the CSR has both a direct and indirect effect on SME competitive performance, precisely as some previous authors had suggested (Aguinis and Glavas, 2012; Miras et al., 2014). Although CSR has been discussed mainly in the context of larger businesses, outcomes indicate that it can be used by SMEs managers as a strategic tool for enhancing the competitiveness (Turyakira et al., 2014).

The evidence found has confirmed the usefulness of the scale developed by Lechuga (2012) to measure the level of CSR practices implemented in SMEs. Along with other kind of alternatives for measuring the socially responsible behaviour of businesses, such as the measures proposed by Marín et al. (2012) or Gallardo-Vázquez et al. (2013), the measure validated in this paper reflects an alternative conceptualization of CSR from the stakeholder view. Thus, our results confirm a scale with an internal structure comparable to the scales of Turker (2009) or Battaglia et al. (2014), with the attractiveness that our measure has been specifically validated for SMEs of any sector.

Moreover, the model estimation and the measurement validation of this formative variable corroborate the relevance that each dimension has to represent a heterogeneous facet of a socially responsible behaviour. Of the four stakeholders that make up this variable (environment, employees, society and customers), the practices attending to employees, environment and customers contribute to the CSR performance to a higher extent and, consequently, practices for these three stakeholders will further enhance the final competitive performance. In this regard, our outcomes confirm those statements that point to employees as the stakeholder with the greatest potential to impact on competitiveness, mainly due to their ability to increase or decrease the levels of productivity of SMEs and their role in the value chain of any company (Jenkins, 2006; Spence, 2007; Hammann et al., 2009; Cegarra-Leiva et al., 2012). On the other hand, in relation to the environment and customers, our results support the need to plan a socially responsible strategy that emphasizes the benefits that these two stakeholders can offer (Murillo and Lozano, 2006). Thus, this work helps to expand the current literature about the positive effect that the commitments with the environment and customers have on business performance (Aragón-Correa et al., 2005; Chavan, 2005; Revell et al., 2010; Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández, 2014a).

At the same time, a new option to measure competitive performance has been validated. The reliability of its inner model, with similar indicators that have been employed in some previous measures of competitive success or increased competitiveness (Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández, 2013; Turyakira et al., 2014), allows managers to improve their knowledge about the real effects of CSR practices on firm performance, specifically effects on the competitive performance in the medium- and long-term. According to our expectations, it should be regarded as a reflective construct composed of two main dimensions: one that includes economic and financial aspects, and another that gathers some measures of competitive differentiation. Therefore, our findings are in agreement with the suggestions of Mishra and Suar (2010) about the need to carry out a double evaluation of firm performance, one from a financial point of view and other from a non-financial perspective.

In regards to the inner model of relational improvements, the adequacy of the multi-stakeholder approach used has been confirmed (Porter and Kramer, 2006; Bhattacharya et al., 2009; Mishra and Suar, 2010). Again, our results support the claims of those who advocate that, due to their direct involvement in the value chain, the relationship with employees (internal stakeholder) and customers (external stakeholder) should be carefully managed, because they will have a higher significant impact on corporate performance than other stakeholders (Berman et al., 1999; Hammann et al., 2009). Managers interviewed are unable to appreciate the potential competitive advantages offered by the establishment and maintenance of good and close relationships with the local community, even though these relationships have often been classified as relevant in some investigations carried out in Common Law countries (Lepoutre and Heene, 2006; Niehm et al., 2008; Sweeney, 2009).

Related to causal effects, the development of CSR practices has a positive influence on competitive performance both directly and indirectly. Therefore, according to Zhao et al. (2010), there is a complementary mediation (i.e. mediated effect and direct effect both exist and point in the same direction). This partial mediation clarifies how the satisfaction of stakeholders’ expectations allows for an increase in the potential benefits that SMEs can obtain, thanks to their good relationships with internal and external stakeholders (Perrini, 2006; Worthington et al., 2006; Fisher et al., 2009; Perrini et al., 2011). Certain previous researchers have pointed out that social responsibility policies contribute to achieve competitive advantages (Porter and Kramer, 2006; Moneva et al., 2007). This work verifies Porter and Kramer's suggestions (2006), since it shows how the integration of CSR within SMEs strategy benefits stakeholders and how, in turn, these internal and external agents react in favour of each company, offering new competitive opportunities. In this regard, it is necessary to understand the true value that CSR generates for the company, by way of shared value. This value emerges to redefine and innovate products or markets; it is a value that provides improvements in the value chain, a value that, ultimately, is always generated considering the interaction between the company and the stakeholders (Porter and Kramer, 2011).

Finally, sometimes it has been argued that one of the main advantages that smaller entities could have is attributed to the inverse relationship between size and proximity to stakeholders (Russo and Tencati, 2009; Hammann et al., 2009; Torugsa et al., 2012). Thanks to their better positioning to establish and maintain close links with their key stakeholders, smaller firms would have greater opportunities to take advantage of some of the competitive benefits from the CSR (Niehm et al., 2008; Iturrioz et al., 2009; Battaglia et al., 2014). In short, this research shows that, regardless of their size, those SMEs that develop socially responsible practices favour positive stakeholder reactions and improve its competitiveness (Lepoutre and Heene, 2006).

Conclusion, limitations, and future researchOne of the main trends of research on CSR has been its potential association with the financial performance. Most authors suggest the social impact hypothesis as a starting point to analyze this association, however the evidence is still unclear, with only a few studies focused in the SMEs field. For this reason, this paper aimed to verify whether, in the field of SMEs, the development of CSR practices also influences business performance. To tackle this objective, empirical data were drawn primarily from personal interviews carried out in early 2011 with more than 481 Spanish SMEs managers. Thus, the large sample of SME's enables us to argue our findings from a broad perspective and close to business reality.

Firstly, the research conducted offers a new way to evaluate the performance of socially responsible companies, adapted to SMEs. Along with the scale proposed by Gallardo-Vázquez et al. (2013), this paper provides to Spanish managers an alternative tool for starting to learn how to embrace and evaluate the CSR: a scale. According to Ortiz and Kühne (2008), the strategic decisions surrounding the socially responsible behaviour of a company can become a source of competitive advantage; thus, managers and owners have the opportunity to take advantage of that which the development of CSR practices provides. On the basis of stakeholder theory, this scale can be considered as a guide or easy-to-use checklist, which involves 24 socially responsible practices with four key stakeholders (in order of relative relevance): employees, environment, customers and society.

According to outcomes reached, the priority management of employee and customer issues contributes more to the achievement of competitive performance than the management of environmental practices and, especially, the development of practices related to society. As Hammann et al. (2009) claimed, the priority management that SMEs use with their stakeholders will be crucial to value generation. The role of relational improvements as a mediating variable emphasizes the relevance of the good management of employees to improve business performance and highlights the importance of this stakeholder in the CSR of SMEs (Turker, 2009). On the contrary, regardless of the presence of the mediating variable, the CSR practices related to society are those that contribute least to increase competitive performance.

The contrast of the full model has allowed us to provide evidence to support the hypothesis of social impact in the context of SMEs. Considering the mediating effect or not, results confirm the existence of a positive and significant causal relationship between the level of CSR practices and competitive performance. On this point, it is necessary to highlight that the inclusion of a mediating variable in the model weakens the relationship intensity between CSR and performance, enough to state that there is a partial mediation. In this regard, as Surroca et al. noted (2010), the debate around CSR and business performance linkage is open. This paper exemplifies that there are some omitted variables that should be considered in models proposed to explain the relationship between these constructs.

To sum up, it has been confirmed that the development of CSR practices promotes strengthening of linkages that SMEs have with their stakeholders and that this improvement, in turn, positively affects competitiveness (Fitjar, 2011; Battaglia et al., 2014; Turyakira et al., 2014). At the same time, the validity of the CSR variable used and the relevance of taking into account the effect of the relational improvements confirm the suitability of the stakeholder theory as the main approach to analyze the relationship between CSR and competitiveness (Perrini et al., 2011).

The results and conclusions drawn from this study should be assumed considering certain limitations. First, the evidence found can only be extrapolated to the SME field, mainly to small enterprises; comparisons to research focused on larger firms should be made with caution. Furthermore, because the strategy of this type of organization is highly conditioned by the attitude and values of the owners/managers, results may differ significantly for a sample of Anglo-Saxon companies. Another limitation is related to respondents. Although most collected information for the quantitative study was obtained from interviews with those responsible for socially responsible management, it should be noted that the data method relied on respondents’ subjective reporting of their firm's CSR practices, relational improvements and competitive performance.

Other most common limitations are those deriving from the measurement of the constructs or from the methodology used. For instance, while in this paper the theoretical approach of stakeholders has been used to measure the level of CSR practices, other studies contemplating SMEs have opted for a more classical approach of CSR, focusing on the triple bottom line (Torugsa et al., 2012; Gallardo-Vázquez et al., 2013). Related to structural equation modelling applied and our data, one of the main constraints of our analysis could be the potential endogeneity problem between CSR and competitive performance (García-Castro et al., 2010). However, we understand that the evaluation of the level of CSR performance is not more than the result of socially responsible policies and strategies necessarily undertaken in advance and that, on the other hand, our measure of competitive performance reflects a momentary assessment of business performance. In any case, we recommend the use of lagged performance indicators to solve this limitation.

Finally, while in this paper only the mediating effect of the SME relational capacity has been considered, studies carried out in large companies suggest that there could be other intangible mediating factors, such as human capital or reputation (Surroca et al., 2010), innovation (Blanco et al., 2013) or advertising intensity (Hull and Rothenberg, 2008; Luo and Bhattacharya, 2009). Moreover, we are aware some researchers have considered different organizative characteristics in addition to firm size as control variables, such as the sector, the level of profitability, the leverage or the family character, among others. For instance, it would be expected that enterprises belonging in sectors with a high social or environmental risk had stronger causal effects and that, therefore, a stratification of the sample by sectors helped to assess in which sectors the CSR has more relevance as a source of competitive advantages (Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández, 2013). In this regard, as a moderator variable, it could be studied if companies belonging to more CSR sensitive sectors are able to achieve a higher firm performance or, conversely, if CSR practices do not offer competitive advantages in this kind of sectors, considering that any sustainable behaviour would become normalized and it would not offer new differentiation opportunities.

In addition, to overcome some of limitations above, future research could be carried out selecting a sample of non-Latin SMEs. In this way, the legal origin could be evaluated as a control variable. It would also be advisable to combine subjective measures of competitive performance with some kind of objective measure of financial performance. This would let us test whether the causal relationship found from respondents’ perceptions is consistent with the real economic and financial situation of their companies. To finish, focusing on the structural model, the inclusion of certain mediating variables identified in the literature could help improve the total variance explained of business performance and design a more detailed strategic plan.

Authors appear in strict alphabetical order.

This research has been developed as part of the project titled “Corporate Social Responsibility, SMEs, Region of Murcia” (ref.: 12003/PHCS/09) funded by the Seneca Foundation, the Regional Agency for Science and Technology, through the call for “Aid for the Completion of Research Projects in Humanities & Social Sciences” Seneca Program 2009.

Tel.: +34 956015493.

Tel.: +34 956015431.

Tel.: +34 868883814.

The term “performance” is used in this research to represent how successful a company is. Different kinds of “performances” can be identified depending on the nature of the measures employed in order to evaluate how well firms do specific activities related with any sphere (financial performance, social performance, environmental performance, competitive performance, etc.).

By “micro-enterprises”, authors refer to firms with less than 10 employees and a turnover no more than two million Euros.

Only size was considered as a control variable to avoid the above specification of a conceptual model in which the number of control variables exceeds the number of main variables under study. We are aware some researchers have employed as control variables different organizative characteristics, such as the sector, the level of profitability, the leverage or the family character, among others.

More information about this company can be found by going to: http://consultorescsa.com/.

It should be noted that, as we expected, the pilot survey confirmed that respondents from bigger companies tended to show a greater knowledge about CSR and socially responsible behaviour. Additionally, larger companies with departments or a person responsible for sustainable issues answered the questionnaire easier and faster than smaller companies. It was, therefore, decided to avoid any technical term that could hinder the understanding of questions.