This study examines emerging market firms that adopt corporate governance standards similar to those in the US. The investigation highlights the impact governance standards may have on corporate risk taking, as measured by stock return volatility, under varying political and socioeconomic regimes. In a cross-sectional time-series setting, the analysis reveals that enhanced governance standards are associated with risk reductions among US domiciled firms, cross-listed American Depository Receipt companies (ADRs) and non-cross listed emerging market (EM) firms. The effect of these governance standards on risk taking, however, does not deviate considerably between cross-listed ADRs that are exposed to Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) mandated regulations and non-cross-listed EM firms that are not subject to the same regulatory constraints. Also, in some respects, Chinese firms seem to exhibit corporate behavior that is contrary to that of the rest of the world.

A considerable body of literature supports the notion that the corporate governance environment (i.e., effective internal control systems and board oversight, reduction in risk taking behaviors, increase in firm value) in the US has improved since the passage of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) in 2002 and the promulgation of US governance standards set by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 2003 (Beasley et al., 2009; Chang and Sun, 2009; Chhaochharia and Grinstein, 2007; Cohen et al., 2008, 2010; Jain et al., 2008; Wang, 2010). Also, given audit committees’ strengthened role in monitoring the financial reporting process and heightened responsibility for reporting accuracy, firms have become more conservative during the SOX era (DeZoort et al., 2008). This is substantiated by research showing a reduction in the acquisition of risky investments as new governance rules are implemented (Bargeron et al., 2010; Cohen et al., 2007; Shadab, 2008).

Few studies have examined the relationship between governance and risk behavior of firms operating in the emerging markets (Braga-Alves and Morey, 2012; Chang et al., 2015). It follows then that scant research has been dedicated to the governance – risk relation among cross-listed EM firms that are exposed to SEC regulations through the issuance of an American Depository Receipt (ADR) or non-cross-listed EM firms (Jayaraman et al., 1993; Litvak, 2007a, 2007b, 2008). Currently, the literature lacks an overarching theoretical model that depicts international corporate convergence in which firms commit to more rigorous regulatory and disclosure standards as a form of “bonding” in an effort to strengthen their governance while reducing their exposure to agency costs so that they may remain competitive both in local and global markets. To build our theoretical model, we employ four individual rules to determine if the riskiness of both cross-listed (ADRs) and non-cross-listed EM firms is affected by US best practices governance standards. Each of the rules are compulsory for firms listed on the NYSE or NASDAQ and identified in Section 303A of the New York Stock Exchange's (NYSE) Listed Company Manual.

Specifically, the four mandated rules employed are: the establishment of three independent committees (i.e., nomination, compensation and audit committees), independent directors, duality of the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and the existence of a corporate ethics policy. The rules are employed to determine (1) if EM firms that adopt standards of corporate governance set in the US have the same impact on risk taking as US firms; and (2) if the effect of corporate governance on risk taking measures differs between cross-listed ADRs that are subject to US governance standards and non-cross listed EM firms that are not held to those standards.

Because of their potential for double-digit economic growth and commensurate investment opportunities, the emerging markets garner a great deal of interest. Nonetheless, the multifaceted risks confronting investors at both the company and national levels has created potential impediments to the inflow of capital. One such impediment is a perception that shareholders in the emerging markets are left relatively unprotected by lax corporate governance standards (Gibson, 2003; Klapper and Love, 2004). To overcome this perception, firms based in the emerging markets pursuing global capital may elect to “migrate” toward exchanges with more stringent governance standards than their home market, thereby “bonding” their commitment to such standards (Abdioglu et al., 2015; Coffee, 1999, 2002; Stulz, 1999). This suggests that the relatively rigorous governance standards of US exchanges may add to the attractiveness of cross-listing through an ADR. This is especially true for Level 2 and Level 3 ADR programs that entail listing on an exchange (i.e., NYSE, AMEX or NASDAQ) and commit firms to governance standards equivalent to those of US firms (Boubakri et al., 2010). Coffee (2002) further argues that global competition for corporate listings and trading volume will foster an enhanced regulatory environment by market exchanges or by “firms seeking to distinguish themselves”. To compete for capital, EM economies will find it necessary to impose more stringent corporate governance standards and this is especially applicable to countries seeking to fuel growth. In this study, we examine the best performing EM countries that are identified by Bloomberg's 2014 Emerging Markets rankings.

In an effort to identify sources of risk and potentially viable control mechanisms, some researchers have investigated country-specific governance practices among the emerging markets. These studies, however, have delivered mixed outcomes regarding the types of practices companies should adopt in order to fashion a more effective governance environment (Abdoli and Royaee, 2012; Abdullah, 2006; Chang et al., 2015; Gibson, 2003; Jaikengkit, 2004; Johnson et al., 2000; Klapper and Love, 2004; Lang et al., 2003; Lattemann, 2014; Lee and Yeh, 2004; Mitton, 2002). Some research focuses on ADRs and the impact of governance mechanisms on investment decisions, financial performance and other firm attributes. These studies either employed aggregated emerging and developed market data (Braga-Alves and Morey, 2012; Chira, 2014; Li, 2014) or market-wide governance rankings or governance attributes related to the legal protection of investors rather than evaluating individual governance standards imposed by the US authorities (Aggarwal et al., 2007; Boubakri et al., 2010; Doidge et al., 2009). Consequently, there remains little solid evidence to inform investor opinions regarding the impact enhanced corporate governance structures have on firm-level risk in the emerging markets or the effect cross-listing in the form of an ADR has on a firm's risk.

To analyze the relation between corporate governance and risk, we employ a two-step GLS random effects model and firm-specific data on a large sample of US firms and companies operating in EM countries covering the 2008–2014 period. In an attempt to isolate the effect of US best practice governance rules on risk taking behavior in the emerging markets, it is important to compare US firms, that are subject to SEC regulations, to cross-listed ADR firms that are most like US firms in that they are partially bounded by the same regulations, and to non-cross-listed EM firms that are not subject to these regulations at all.

This study has theoretical and practical implications for international corporate governance practices in that it identifies mechanisms that could enhance investor trust leading to new opportunities for investors and increased capital for the emerging markets. Using a large sample of American (i.e., US) firms, cross-listed and non-cross-listed EM firms, we find that stronger governance is associated with lower risk among firms in the US, cross-listed ADR firms and non-cross-listed EM firms (Braga-Alves and Morey, 2012; Gibson, 2003; Haripriya et al., 2006). Also, we find that some of the governance related parameter estimates of the non-cross listed EM firms (i.e., Committees, CEO Duality and Ethics Policy) are affected by the exclusion of Chinese companies from the sample, both with regard to the sign of the coefficient as well as the statistical significance. These results are consistent with the existing literature in that they indicate that the negative relationship between risk and governance is stronger for Level 2 and Level 3 ADRs; firms in which governance and disclosure requirements are more restrictive than for those of the Level 1 ADRs (Boubakri et al., 2010; Lel and Miller, 2008). In general, it appears that US governance standards impose an element of risk mitigation among EM firms, and the effect of these standards on risk taking behavior does not appear to differ between cross-listed ADRs and non-cross-listed EM firms.

A significant managerial implication of the study is that separating the position of chief executive from that of the chairman is important for the reducing risks that might arise from an overly powerful CEO. Additionally, the results suggest that the establishment of a greater number of independent committees is associated with more effective managerial oversight by the board of directors (BOD). Furthermore, the institution of a formal ethics policy is an important element in establishing an effective corporate governance regime and mitigating dysfunctional behavior and unwarranted risk. It is important to point out, however, that managers as well as investors should remain cognizant of the challenges related to applying western notions of ethics to China (Irwin, 2012); ethics policies do not serve as a disincentive to risky behavior, but appear to be a form of “window-dressing” among Chinese firms. In order to alleviate illegal activity and protect investors, a more effective public administration, dedicated to the enforcement of globally recognized ethical policies, will be required to successfully implement a culture of responsible corporate management.

The primary goal of strengthening corporate governance is to protect minority shareholders and creditors from expropriation by managers and controlling shareholders (La Porta et al., 2000). However, because the application of recognized corporate governance rules is a relatively recent development in the emerging markets, local investor protection laws are not as effective as US securities law (Claessens and Yurtoglu, 2013). By providing evidence that EM firms that implement these standards actually reduce risk, we show that governance, as it is applied in the developed world, can be effective in emerging countries. By adopting US best practice governance standards, EM firms can effectively signal to global markets that they have taken steps to diminish the risk of expropriation.

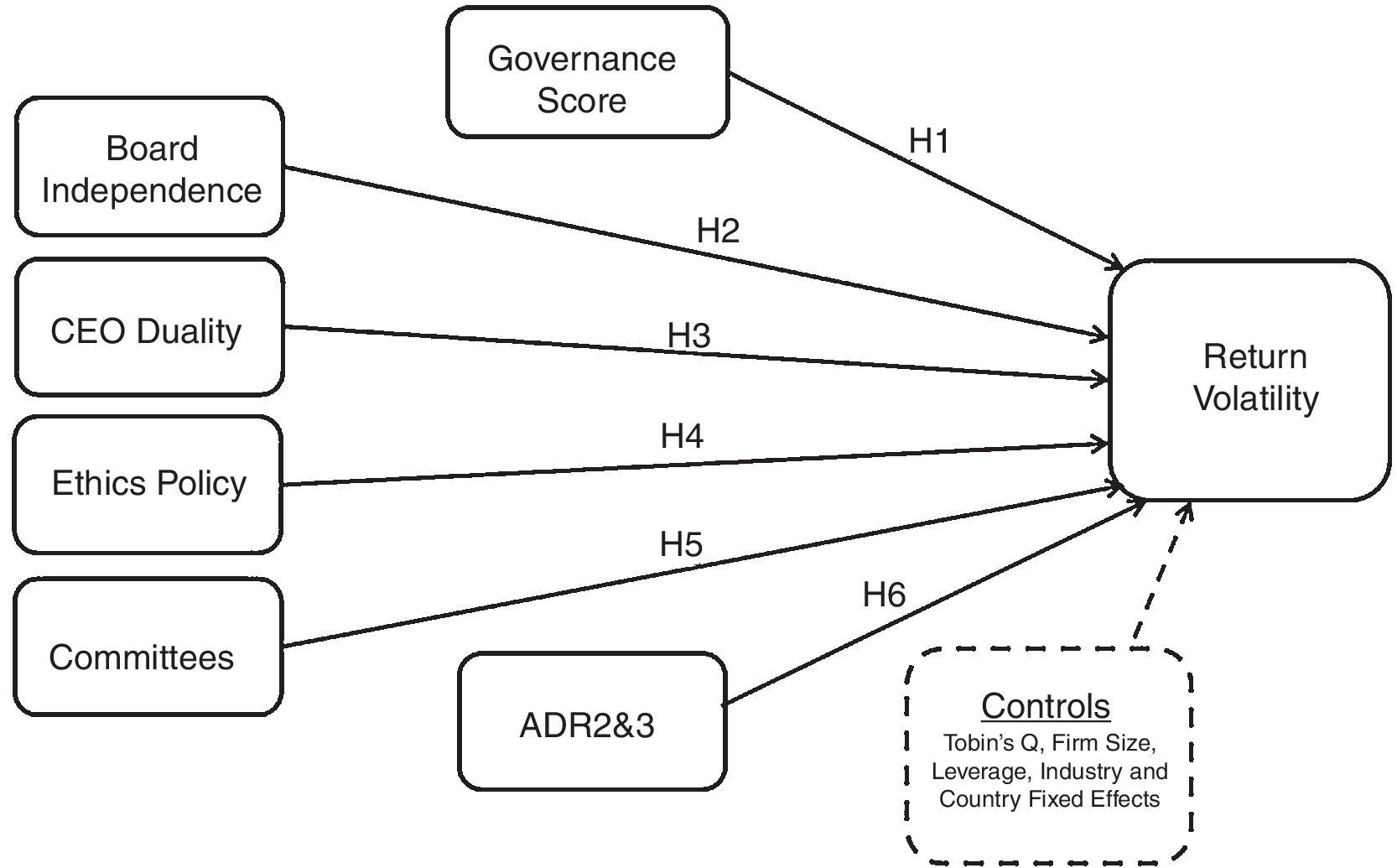

Our conceptual model is provided in Fig. 1. Consistent with a broad set of evidence from the corporate governance literature, we depict the method by which stronger corporate governance decreases a firm's risk taking (operationalized as return volatility). Moreover, we test our primary intended contribution: to assess whether SEC mandated US governance rules, namely greater board independence, increasing the number of committees established to support and monitor the board, and the existence of an ethics policy reduces corporate risk taking, while CEO duality increases risk-taking among cross-listed ADRs and non-cross listed EM firms. Finally, to determine if increased global competition incentivizes emerging markets to converge toward US governance standards, we compare the results on cross-listed, level 2 and level 3 ADRs to non-cross-listed EM firms.

The next section of the paper synthesizes the extant literature to provide a theoretical background for this study and develops the hypotheses regarding the impact of governance standards on risk taking behavior across international capital markets. The subsequent section provides a description of the data sample and introduces the research method. The following section presents the empirical results. The final section provides conclusions, limitations and potential future research.

Conceptual framework and hypotheses developmentCorporate governance in the emerging marketsTo address the forces driving corporate structure as well as corporate decision making, we appeal to agency theory, which holds that managers do not necessarily act in the best interest of their shareholders given that both parties are utility maximizers whose interests likely diverge (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). In this regard, corporate governance standards serve as an important mechanism with which to effectively limit aberrant managerial activities and thereby reduce corporate risk taking. In a competitive global market, in which firms raise capital and penetrate new markets, agency theory predicts that non-cross-listed EM firms and ADR firms should have similar incentives regarding the strength of corporate mechanisms that mitigate the potential for the expropriation of shareholder and minority interests.

Bonding theory also applies to corporate decision making in that it contends that corporations operating across different political and socioeconomic environments tend to converge toward “higher regulatory or disclosure standards in order to implement a form of bonding under which firms commit to governance standards more exacting than that of their home countries.” (Coffee, 1999, p. 23) As a result, the US securities law, SOX (2002), acts as a form of best practice that imposes corporate transparency, constrains the self-serving interests of all stakeholders and essentially blends global securities markets.

Although cross-listed firms seem to have more incentives to “bond” themselves to a stricter regulatory regime in an attempt to increase the value of their publicly traded shares (Coffee, 2007), non-cross listed firms also have a similar motivation in that they are also involved in international transactions such as exporting their products, foreign investments and/or relationships with foreign business partners (Litvak, 2007a, 2007b). As a result, non-cross listed EM firms will tend to apply US best practice governance standards in order to attract foreign investments and to remain competitive in the global market, although the standards are not directly imposed on these firms.

Since the early 1990s, there has been a concerted effort to establish corporate governance principles that mitigate incentive problems associated with the separation of management and ownership within corporations. To address perceived shortcomings and to alleviate the occurrence of newsworthy corporate scandals, the US Congress passed and President George W. Bush signed into law the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). By 2006, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) implemented the provisions of the new law and approved the corporate governance standards that are codified in Section 303A of the New York Stock Exchange's (NYSE) Listed Company Manual and NASDAQ's Rule 4000.

The governance rules established by SOX and the SEC confront the problems associated with agency theory (Ross, 1973; Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Fama and Jensen, 1983) by strengthening the control mechanisms placed on the firm's management with regard to corporate risk-taking. In this study we examine some of the key features of US best practices governance rules in the context of cross-listed ADRs and non-cross-listed EM firms. Specifically, we analyze the risk impact associated with the number of independent board members, the number of active committees (i.e., audit, compensation and nomination) and the existence of an established corporate ethics policy. Also, although not explicitly included in the SOX regulations but because of its significance in the corporate governance literature, we examine the impact of CEO duality, referring to the division of responsibilities between the chairman of the board and the chief executive officer (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., 2006; Conyon and Peck, 1998; Daily and Dalton, 1994; Imhoff, 2003; Jensen, 1993; Mallette and Fowler, 1992).

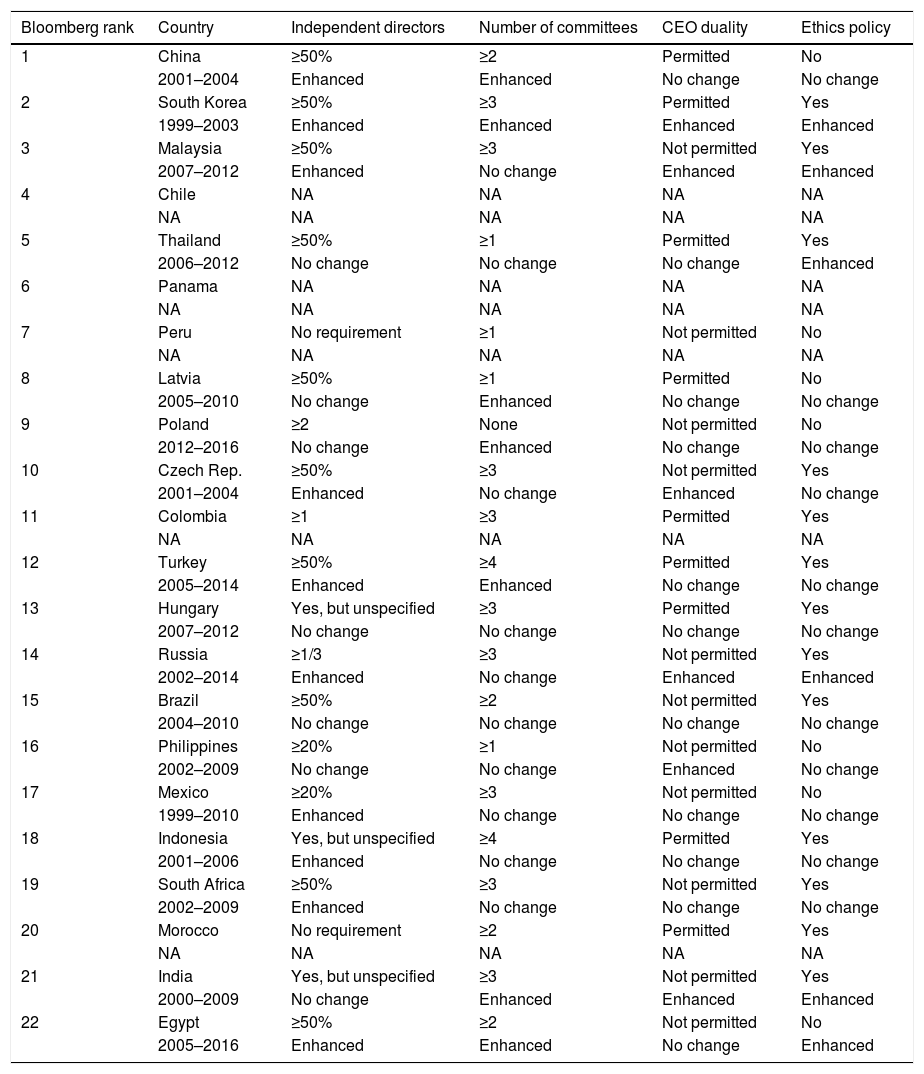

According to the authors’ knowledge, the extent to which global corporate governance standards are converging to a single “best practice” has not been established in the literature. Nevertheless, Yoshikawa and Rasheed (2009) point out that “the extant literature generally examines convergence in terms of the adoption of some elements of the Anglo-American or US governance system and practices by countries and firms outside the Anglo-American zone” (p. 389). To assess the level of convergence toward a US standard by the 22 EM countries, in this study we examine the most recent corporate governance rules established within each of the markets (i.e., 20 of the 22 codes were obtained from the European Corporate Governance Institute1) as well as the change in the codes since the previous revision (17 of the 22 previous codes were obtained from the European Corporate Governance Institute) across the four variables used in the study: the percentage of independent directors, the number of committees, the acceptability of CEO duality and the presence of an explicit ethics policy.

In Table 1, the most recent codes show that ten of the countries require a majority of directors to be independent, while 17 mandate the presence of at least one autonomous director. The minimum number of the committees to be established, as well as their purpose, is cited in 19 of the 20 available codes and 15 of the codes stipulate the formation of at least two. CEO duality is acceptable in 11 countries and a mandated ethics policy is required in 13. Moreover, the most recent revisions of the emerging markets governance standards reveal that in the 17 available, 15 made at least one change with regard to the four relevant variables that brought those standards into closer alignment with that of the US. Furthermore, in no instance have the regulators of an emerging market weakened a governance requirement. In sum, while it would be difficult to argue that the EM countries have converged to a single corporate governance standard that emulates the US, enough commonality exists to suggest that the regulators of these markets are cognizant of the concerns of international investors.

Comparing corporate governance standards in the emerging market.

| Bloomberg rank | Country | Independent directors | Number of committees | CEO duality | Ethics policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | ≥50% | ≥2 | Permitted | No |

| 2001–2004 | Enhanced | Enhanced | No change | No change | |

| 2 | South Korea | ≥50% | ≥3 | Permitted | Yes |

| 1999–2003 | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhanced | |

| 3 | Malaysia | ≥50% | ≥3 | Not permitted | Yes |

| 2007–2012 | Enhanced | No change | Enhanced | Enhanced | |

| 4 | Chile | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 5 | Thailand | ≥50% | ≥1 | Permitted | Yes |

| 2006–2012 | No change | No change | No change | Enhanced | |

| 6 | Panama | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 7 | Peru | No requirement | ≥1 | Not permitted | No |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 8 | Latvia | ≥50% | ≥1 | Permitted | No |

| 2005–2010 | No change | Enhanced | No change | No change | |

| 9 | Poland | ≥2 | None | Not permitted | No |

| 2012–2016 | No change | Enhanced | No change | No change | |

| 10 | Czech Rep. | ≥50% | ≥3 | Not permitted | Yes |

| 2001–2004 | Enhanced | No change | Enhanced | No change | |

| 11 | Colombia | ≥1 | ≥3 | Permitted | Yes |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 12 | Turkey | ≥50% | ≥4 | Permitted | Yes |

| 2005–2014 | Enhanced | Enhanced | No change | No change | |

| 13 | Hungary | Yes, but unspecified | ≥3 | Permitted | Yes |

| 2007–2012 | No change | No change | No change | No change | |

| 14 | Russia | ≥1/3 | ≥3 | Not permitted | Yes |

| 2002–2014 | Enhanced | No change | Enhanced | Enhanced | |

| 15 | Brazil | ≥50% | ≥2 | Not permitted | Yes |

| 2004–2010 | No change | No change | No change | No change | |

| 16 | Philippines | ≥20% | ≥1 | Not permitted | No |

| 2002–2009 | No change | No change | Enhanced | No change | |

| 17 | Mexico | ≥20% | ≥3 | Not permitted | No |

| 1999–2010 | Enhanced | No change | No change | No change | |

| 18 | Indonesia | Yes, but unspecified | ≥4 | Permitted | Yes |

| 2001–2006 | Enhanced | No change | No change | No change | |

| 19 | South Africa | ≥50% | ≥3 | Not permitted | Yes |

| 2002–2009 | Enhanced | No change | No change | No change | |

| 20 | Morocco | No requirement | ≥2 | Permitted | Yes |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 21 | India | Yes, but unspecified | ≥3 | Not permitted | Yes |

| 2000–2009 | No change | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhanced | |

| 22 | Egypt | ≥50% | ≥2 | Not permitted | No |

| 2005–2016 | Enhanced | Enhanced | No change | Enhanced |

This table provides a categorization of the most recent available corporate governance standards and depicts changes in the corporate governance standards from the previous declaration of governance codes to the most recent available in Bloomberg's 22 highest ranked EM countries across four variables. Independent Directors depicts the minimum proportion of board members or the minimum number of board members that must be independent, a requirement of the presence of independent directors with no stated specifics (yes, but unspecified), the lack of a requirement of independent board members (no requirement) or no data are available (NA). Number of committees represents the minimum number of committees that must be formed by the company. CEO duality denotes whether an individual may simultaneously assume the dual role of Chairman of the Board and CEO. Ethics policy indicates if a company is required to have a stated policy of acceptable business practices and ethics for board members, officers and employees. “Enhanced” designates that the code related to that variable has been revised so that it more closely aligns with US corporate governance codes. “No change” denotes that the code has not been changed in that country from the previous declaration of the code to the most recent available.

Certain aspects of the linkage between corporate governance and risk among US firms have been addressed in the literature (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., 2006; Bargeron et al., 2010; Bhojraj and Sengupta, 2003; Cohen et al., 2010). In sum, these studies show that the passage of SOX has increased the pressure on US firms to strengthen their governance mechanisms and discouraged corporate risk-taking. Only a few studies investigate the relation between risk and governance among non-listed EM firms or ADR listed firms. In an earlier study, Jayaraman et al. (1993) examines the impact of ADR listing on the risk and return of cross-listed firms and observed that ADRs generated a higher volatility of returns. Using an event study on matched pairs of cross-listed foreign firms subject to SOX regulation (Level 2 and 3 ADRs), cross-listed firms not subject to SOX (Level 1 and Rule 144A) and non-cross-listed firms, Litvak (2007a) finds that the stock prices of firms facing SOX regulation declined substantially. In a similar study, Litvak (2007b) finds a significant decline in the stock price premium paid for cross-listed firms relative to non-cross-listed firms after the adoption of SOX. In an attempt to investigate the impact of SOX on corporate risk, Litvak (2008) finds that risk declined significantly among firms cross-listed on major US exchanges. Nonetheless, because the sample Litvak uses includes all ADR firms, results for EM firms cannot be isolated. In a study that focuses on a specific set of EM firms, Haripriya et al. (2006) conduct an event study around the September 11th, 2001 attack on New York, focusing on Indian ADRs. The results show that the market risk of these firms (i.e., beta) decreased significantly during the post-event period while the volatility of returns increased in the same period. Braga-Alves and Morey (2012) examined the impact of governance on country and company specific risk, measured by log of sales, ROA, debt to equity ratio, annual growth of sales, CAPEX to sales ratio and standard deviation of weekly returns; employing the governance ratings generated by AllianceBernstein on firms operating in 24 emerging markets. The authors find that corporate governance is stronger in countries with lower political risk, but provide no evidence of a relation between governance and company specific risk.

Overall, the literature reveals that strong corporate governance tends to lead toward risk reduction, but there is a lack of solid evidence to suggest that this effect applies to firms operating in the emerging markets. In this regard, we hypothesize the following:Hypothesis 1 Corporations with stronger corporate governance will reduce risk over time.

This study draws on agency theory to explain how corporate governance might affect risk in different political and socioeconomic environments. Agency theory relies on the assumption that managers are self-interested and hence, in the absence of an effective control mechanism, may pursue personal interests rather than the interests of the firm's owners whom they represent (Fama and Jensen, 1983). Accordingly, corporate governance mechanisms are installed to bolster independence of the board representing the owners/shareholders and oversee the firm's executive management (Beasley, 1996; Cotter and Silvester, 2003; Finkelstein and Hambrick, 1988; Jensen and Meckling, 1976). It follows then that corporate governance standards set by the SEC (2003) requires listed companies to include a majority of independent board members. Corporate boards are the primary internal governance mechanism responsible for monitoring senior managers (Conyon and Peck, 1998; Jensen, 1993). Consequently, boards that include more independent directors should enhance internal control by assessing management more objectively and are more likely to mitigate unwarranted risky behavior on the part of managers (Fields and Keys, 2003). Nonetheless, the efficacy of outside directors in monitoring the top management could be considered suspect in view of major corporate scandals during the early 2000s such as Enron, Worldcom; most of the fraud committed by the managers of these firms were operating under boards of directors (BOD) comprising a majority of independent directors.

There are a number of reasons boards may become ineffective in their oversight. For example, the compensation plans of outside directors with small equity stakes and consequently limited financial incentives might lead to a reluctance on the part of outsiders to spot the fraudulent actions of senior managers (Finkelstein and Hambrick, 1997). Also, the outside directors that are employed by the firm might not be “truly independent” if they possess a material relationship with the listed company, say as previous owners or as former members of the management team. Thus, relying on the assumption that outside directors are truly independent and BODs can work effectively, we expect that firms with a majority of independent directors on their boards will be less likely to expose themselves and their firms to risk in the emerging markets.Hypothesis 2 Corporations with more independent directors on their board will reduce risk over time.

US governance standards do not directly address the separation of the roles of the CEO and the chairman of the board. Research reveals, however, that during the last decade US companies began to modify the two positions so that there was a clearer division of the responsibilities between the board and management (Garrett, 2007; Tuggle et al., 2010). Jensen (1993) argues that the roles CEO and chairman of the board should be separate in order to safeguard shareholders’ interests from the interests of the CEO. Related literature also reveals that CEOs who serve as board chair simultaneously increase the risk of appointing board candidates who do not qualify as “truly independent” (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., 2006; Conyon and Peck, 1998; Imhoff, 2003). While “chairman of the board” may appear as symbolic, agency theory suggests that CEO duality (i.e., holding both positions) violates the separation of management and control. The literature related to the emerging markets is ambiguous regarding the impact of CEO duality. Abdullah (2006) examines CEO duality and financial distress among Malaysian companies and finds that firms whose CEOs act as executive chairman are less likely to experience financial distress as opposed to firms that separate CEO and executive chairman positions. Jaikengkit (2004) uses governance structure variables in a financial distress prediction model on a sample of 56 banks in Thailand to discover that there is no relation between CEO duality and the probability of financial distress.

Although there remain discrepancies in the literature, agency theory focuses on the monitoring role of the board, which should align the interests of the CEO with that of the shareholders (Finkelstein and D’aveni, 1994). When an individual holds both the CEO and chairperson positions, the CEO essentially has been provided the unassailable ability to act as the sole decision making authority within the firm. This concentration of power can negate a board's ability to effectively control or monitor management, or establish a counter-balance to that power (Mallette and Fowler, 1992). Duality increases the likelihood that a CEO will become overconfident with regard to his/her problem-solving ability while underestimating uncertainties, which effects corporate strategy, tactical decisions and outcomes, thereby inclining the firm toward more risk-taking (e.g., targeting unattainable earnings forecasts) (Paul and Yang, 2006; Li and Tang, 2010). Moreover, the risk that the firm undertakes unsuccessful and even value decreasing investment decisions significantly increases (Hayward et al., 2006; Malmendier and Tate, 2008). Therefore, based on agency theory, we hypothesize the following:Hypothesis 3 Corporations with CEO duality will exhibit relatively more risk over time.

In 2003 the SEC set governance standards stipulating that listed firms should establish an ethics policy and code of business conduct for directors, officers and employees that encompass the rules and responsibilities of each party in the organization. These policies tend to deal with the risks associated with accepting gifts, bribery and corruption (Simpson and Taylor, 2013). Obviously, such behavior can lead to an erosion of the firm's reputation, financial penalties and criminal charges, which in turn can increase the company's risks. If the behavior continues, it could lead to large-scale boycotts and/or legal action causing the deterioration of the firm's performance and increased stock price volatility (Boutin-Dufresne and Savaria, 2004). In fact, research also reveals a direct negative relation between corporate social performance, which includes business ethics as a measure and market risk (Orlitzky and Benjamin, 2001). Therefore, in this study we test the following hypothesis:Hypothesis 4 Corporations with formal ethics policies will exhibit less risk over time.

Corporate committees involved in the governance process serve specific functions in that they identify potential courses of action for the full board of directors (Bates and Leclerc, 2009). Corporate governance standards established by the enactment of SOX require listed companies to have separate nomination, compensation and audit committees - each of which is entirely composed of independent directors. Each committee is assigned specific roles and responsibilities related to the identification and amelioration of possible weaknesses within the company's governance structure and execution. For instance, the main role of the compensation committee is to protect shareholders by preventing unwarranted bonuses or salary increases from being awarded to senior executives or other employees. The WorldCom scandal serves as a striking example in which the lack of reasonable compensation policies regarding directors and managers of the company proved disastrous. An investigation revealed that, although lacking the necessary authority, the CEO and CFO granted compensation to “loyal” employees, especially in the finance, accounting and investor relations departments, that exceeded the company's approved salary and bonus plans (Kaplan and Kiron, 2004).

Similarly, nomination committees serve a vital role in directing the process of board appointments and in recommending board candidates for directory positions (Dumitrascu and Gajevszky, 2013). In line with the SOX governance standards that require an independent nomination committee, Ruigrok et al. (2006) find that, among Swiss firms, the existence and composition of nomination committees have a significant effect on the probability that independent directors will be nominated and eventually elected. Similarly, Conyon and Peck (1998) find that companies employing a nomination committee to select directors exhibit significantly more effective board control.

Audit committees assist the board of directors in financial reporting, internal control and risk management. Research supports the view that the enactment of SOX has stimulated audit committees to play a more active role in i) monitoring financial reporting processes; ii) promoting sound financial reporting and iii) enforcing more effective corporate governance mechanisms (Beasley et al., 2009; Cohen et al., 2010; DeZoort et al., 2008; Vera-Munoz, 2005). Abbott et al. (2004) find similar outcomes for the pre-SOX period as well and find that the independence of the audit committee and its activity level, measured by audit committee size, existence of a financial expert and frequency of the audit committee meetings, has a significant negative impact on the frequency of accounting restatements. Similarly, Klein (2002) finds that, for publicly traded US firms in the pre-SOX era, there was higher earnings management (measured by abnormal accruals) in firms having a minority of independent directors in their audit committees. Dionne and Triki (2013) examine the relation between audit committee independence and the risk management activities of companies by using firms’ hedging portfolios as a proxy variable. They find that firms with audit committees composed of only independent directors are more likely to engage in risk averting hedges than firms that do not meet this independence criterion.

Overall, early studies reveal that committees have a significant role to play in solidifying board control, mitigating personal managerial incentives and risk bearing behaviors, and in avoiding the consequences of market volatility (Conyon and Peck, 1998; DeZoort et al., 2008; Dionne and Triki, 2013). The potential importance of committees in the governance process leads to the following hypothesis:Hypothesis 5 Firms with a greater number of committees will exhibit less risk over time.

ADR issues are classified within one of three categories: Level 1, 2 or 3. Level 1 ADRs are subject to the least amount of regulatory oversight, are exempt from SOX compliance requirements, and because of this minimal oversight, trade only in the over-the-counter market. Level 2 and level 3 ADRs are subject to all of the registration and reporting requirements mandated by the SEC including full compliance with SOX mandates related to accounting and disclosure standards. While both level 2 and 3 ADRs trade on the major US stock exchanges such as the NYSE, AMEX and NASDAQ; only companies issuing a level 3 ADR may raise capital through a public offering.2

Because of the relatively stringent regulatory restrictions placed on issuers of level 2 and level 3 ADRs, “agency theory” (Ross, 1973; Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Fama and Jensen, 1983) suggests that investors holding these assets face less risk. Relatedly, “bonding theory” (Coffee, 1999, 2002; Stulz, 1999) holds that foreign firms voluntarily accept these enhanced standards to signal their commitment to good governance. Regardless, there is decidedly mixed evidence on the effectiveness of these control mechanisms as it relates to risk.

Contrary to agency and bonding theories, firms that voluntarily accept the increased regulatory restrictions of a level 2 or 3 program typically see a decrease in the performance of their stock. Gozzi et al. (2008) find that the Tobin's q of level 3 ADRs falls significantly in the year following “internationalization”. Similarly, Litvak (2007a, 2007b, 2008) finds that, after the enactment of SOX, the stock price performance of cross-listed firms is significantly negative, although the change in unsystematic risk remains unclear. The effect of SOX on level 2 and level 3 ADR firms is further examined by Li (2014) to include both the short- and long-term impact and finds that the additional costs imposed by the law significantly outweigh the benefits of cross-listing.

In accordance with agency and bonding theories, the impact of enhanced corporate governance and disclosure standards imposed upon level 2 and 3 ADRs appears to have a mitigating effect on the risks faced by dispersed shareholders. Doidge et al. (2009) find that foreign firms are less likely to list on a major exchange (as a level 2 or 3 ADR) if controlling shareholders benefit from the consumption of private benefits; however, such firms do not show the same reluctance with regard to listing over-the-counter (as a level 1 ADR). The enhanced corporate governance associated with cross-listing on an exchange also appears to provide a means by which poor performing managers can be identified and terminated (Lel and Miller, 2008). Additionally, Shi et al. (2012) provide evidence that information asymmetry is reduced when a foreign firm voluntarily commits to US disclosure rules. Finally, Litvak (2014) finds that the enactment of SOX reduced the return volatility and leverage and increased the balance sheet liquidity of level 2 and level 3 ADRs concluding that SOX forced the managers of cross-listed firms, subject to US regulatory restrictions, to accept fewer risks.

The evidence related to agency theory and bonding theory can be perceived as mixed as it relates to the risk of cross-listed firms; especially in the post-SOX era. Nonetheless, it seems reasonable that firms willing to voluntarily commit to the enhanced regulatory regime of US exchanges by listing as a level 2 or 3 ADR also adopt a corporate governance structure that facilitates the reduction of the risks faced by their shareholders. We therefore test:Hypothesis 6 Level 2 and level 3 ADRs will exhibit less risk than level 1 ADRs over time.

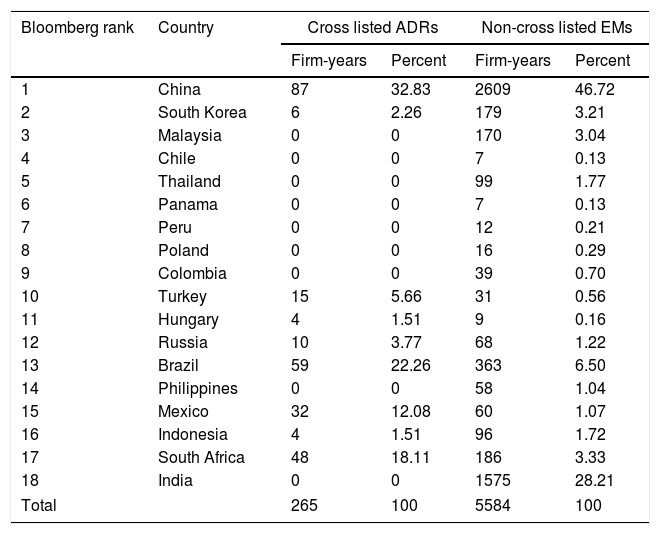

In this study we analyze the impact of corporate governance on the risk taking behavior of a sample of firms based in 22 EM countries as well as a sample of US-based firms over a period extending from 2008 to 2014. The sample of US firms comprises those listed on the NASDAQ and NYSE because the SEC governance rules enacted after SOX are obligatory. The EM firms are drawn from the 22 best performing emerging markets for the year 2014 as ranked by Bloomberg Visual Data. Bloomberg's ranking is based on each country's GDP growth, inflation, the level of government debt, the annual change in government debt, currency purchasing power, and total investment as percentage of GDP. As these emerging countries maintained significant economic progress over the previous decade and became attractive business and investment hubs for the rest of the world, the investigation of these markets in terms of governance implications and risk behavior has become important. Unfortunately, Morocco, Latvia, Egypt and the Czech Republic have been dropped from our EM sample because of missing firm-year observations. The study is limited to Bloomberg's top 22 (essentially, top 18) emerging markets strictly because of data limitations. These limitations most likely stem from the fact that the markets omitted from the list lack the infrastructure, liquidity, market activity or even willingness to collect or maintain accurate records. Table 2 provides the list of EM countries identified for this study.

Country distribution of sample.

| Bloomberg rank | Country | Cross listed ADRs | Non-cross listed EMs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm-years | Percent | Firm-years | Percent | ||

| 1 | China | 87 | 32.83 | 2609 | 46.72 |

| 2 | South Korea | 6 | 2.26 | 179 | 3.21 |

| 3 | Malaysia | 0 | 0 | 170 | 3.04 |

| 4 | Chile | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.13 |

| 5 | Thailand | 0 | 0 | 99 | 1.77 |

| 6 | Panama | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.13 |

| 7 | Peru | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0.21 |

| 8 | Poland | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0.29 |

| 9 | Colombia | 0 | 0 | 39 | 0.70 |

| 10 | Turkey | 15 | 5.66 | 31 | 0.56 |

| 11 | Hungary | 4 | 1.51 | 9 | 0.16 |

| 12 | Russia | 10 | 3.77 | 68 | 1.22 |

| 13 | Brazil | 59 | 22.26 | 363 | 6.50 |

| 14 | Philippines | 0 | 0 | 58 | 1.04 |

| 15 | Mexico | 32 | 12.08 | 60 | 1.07 |

| 16 | Indonesia | 4 | 1.51 | 96 | 1.72 |

| 17 | South Africa | 48 | 18.11 | 186 | 3.33 |

| 18 | India | 0 | 0 | 1575 | 28.21 |

| Total | 265 | 100 | 5584 | 100 | |

This table presents country distribution of the cross-listed ADRs and non-cross listed EM firms. All firms are from the emerging countries in Bloomberg's Best Emerging Markets 2014 list. Morocco, Latvia, Egypt and Czech Republic are dropped off of the sample as their data includes significant amount of missing firm-year observations.

Within the sample of EM firms, we distinguish between those whose equity trades outside US exchanges exclusively and those that are cross-listed and trading as ADRs. This allows us to isolate the impact of SEC mandated governance standards. Our sample of ADRs excludes Malaysia, Chile, Thailand, Panama, Peru, Poland, Colombia, Philippines and India, either because these ADRs do not exist or the data are missing for these countries. Additionally, we distinguish between the Level 2 and Level 3 ADR programs from the Level 1 ADRs to allow for an examination of a possible incremental effect of SOX (2002) on these firms’ governance policies. In total, the sample comprises 7355 US firm-year observations of companies that are publicly traded on the NASDAQ and NYSE; 5584 non-cross listed EM firm-year observations of companies that are publicly traded on the stock market of 18 EM countries and 265 cross-listed ADR firm-year observations of companies trading on both markets in the US and one of the EM countries in our sample.

To qualify for the sample, we require contiguous, annual governance variables for a given firm over the 2008 to 2014 period. Our analysis is restricted to this seven year period because of the scarcity of reliable governance data before 2008. Not all of the EM firms are represented during our sample period either because a stock de-listed from the US market, or because reliable, contiguous governance data were not available. The financial and corporate governance data on the EM and US firms were accessed through the Bloomberg Database, which provides market information as well as firm specific data for all sectors globally. Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB) codes are used to capture industry effects; firms are categorized into 10 industries: oil and gas, basic materials, industrials, consumer goods, health care, consumer services, telecommunications, financials, utilities and technology.

Variable measurementWe measure risk as the annualized standard deviation of a firm's weekly stock returns, requiring at least 6 months of data for each year of the analysis (e.g., Bargeron et al., 2010; Boutin-Dufresne and Savaria, 2004; Braga-Alves and Morey, 2012; Chang et al., 2015; Jayaraman et al., 1993; Lang et al., 2003; McGuire et al., 1988). Our corporate governance data are retrieved from Bloomberg. To determine a company's overall governance structure, we use a governance disclosure score that is estimated by the Bloomberg Professional database (Baldini et al., 2016; Giannarakis et al., 2014; Hayat and Hassan, 2017; Lai et al., 2016; Nollet et al., 2016). The score is based on the extent to which a company discloses its governance structure. A governance disclosure score can range from 0.1, for companies that provide minimal disclosure, to 100, for those that disclose every data point collected by Bloomberg. Each data point is weighted by Bloomberg in terms of importance; the board of directors data carrying the greatest weight. Also, the score is tailored to different industries, so that each company is evaluated only in terms of its specific industry sector. In order to analyze the impact of each of the governance standards on firm risk, we employ the following variables: the proportion of independent board members, the number of governance related committees (i.e., audit, compensation and nomination), the size of the board, an indicator variable representing the dual nature of the CEO's role that is coded 1 if the CEO also serves as the chairman of the board, and an indicator variable that is coded 1 if the company has a formal ethics policy.

To control for potentially confounding, exogenous factors, we include a number of company, industry and country-level variables. At the firm-level we control for leverage, investment opportunities and size effects. Leverage, as measured by the ratio of total debt to total assets, can have a significant impact on the total and systematic risk of a firm through its cost of capital (Adrian and Shin, 2010; Lev, 1974; Tuttle and Litzenberger, 1968). Tobin's Q is measured as the sum of a firm's market capitalization, total liabilities, preferred equity and minority interest, all divided by total assets. As such, Tobin's Q captures the market value of a firm and also provides a robust measure of investment and growth opportunities, because it includes preferred shares as well as the firm's minority interests in other companies that could capture strategic partnerships (Litvak, 2007a, 2007b, 2008). Size is commonly considered a pricing risk factor because of its impact on the mean and volatility of returns (Fama and French, 1993). Moreover, larger firms tend to have access to a larger pool of resources for R&D and investment opportunities (Core et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2014). In this study, size is computed as the log of a firm's total assets. Industry effects are captured using indicator variables for each Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB) code (Beasley et al., 2000; Donaldson and Davis, 1991). Finally, we include an indicator variable for each country in the data set to control for possible fixed effects related to the national origin of a firm (Lang et al., 2003; Lel and Miller, 2008).

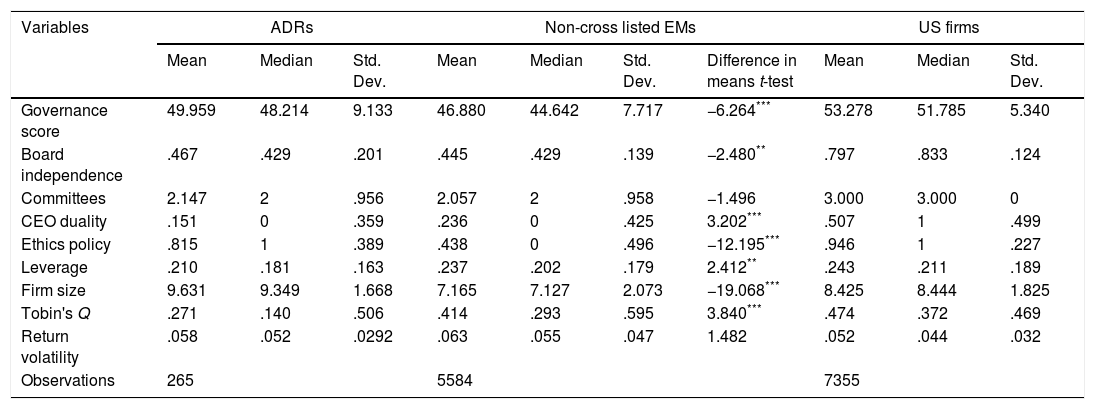

Descriptive statisticsTable 2 provides the distribution of cross-listed ADR firms and non-cross listed EM firms across national origin. The table reveals that over 85% of the ADR firms in the sample originate in either China (32.83%), Brazil (22.26%), South Africa (18.11%) or Mexico (12.08%), while almost 72% of non-cross listed EM firms are located in either China (46.72%) or India (28.21%). Summary statistics for the cross-listed ADRs, non-cross listed EMs and US firms are presented in Table 3. Overall, ADR firms generate a significantly higher governance disclosure score than the EM firms. Also, in concurrence with the extant literature, ADR firms have a greater percentage of independent directors on their boards, less incidence of CEO duality and are much more likely to have forged a formal ethics policy (Lel and Miller, 2008; Litvak, 2014; Shi et al., 2012). We do not, however, find statistical evidence that ADR firms employ a greater number of committees, nor does there appear to be a statistical difference in the riskiness (measured as the volatility of stock returns) between ADRs and EM firms.

Descriptive statistics for cross listed ADRs, non-cross listed EMs and US firms.

| Variables | ADRs | Non-cross listed EMs | US firms | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | Difference in means t-test | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | |

| Governance score | 49.959 | 48.214 | 9.133 | 46.880 | 44.642 | 7.717 | −6.264*** | 53.278 | 51.785 | 5.340 |

| Board independence | .467 | .429 | .201 | .445 | .429 | .139 | −2.480** | .797 | .833 | .124 |

| Committees | 2.147 | 2 | .956 | 2.057 | 2 | .958 | −1.496 | 3.000 | 3.000 | 0 |

| CEO duality | .151 | 0 | .359 | .236 | 0 | .425 | 3.202*** | .507 | 1 | .499 |

| Ethics policy | .815 | 1 | .389 | .438 | 0 | .496 | −12.195*** | .946 | 1 | .227 |

| Leverage | .210 | .181 | .163 | .237 | .202 | .179 | 2.412** | .243 | .211 | .189 |

| Firm size | 9.631 | 9.349 | 1.668 | 7.165 | 7.127 | 2.073 | −19.068*** | 8.425 | 8.444 | 1.825 |

| Tobin's Q | .271 | .140 | .506 | .414 | .293 | .595 | 3.840*** | .474 | .372 | .469 |

| Return volatility | .058 | .052 | .0292 | .063 | .055 | .047 | 1.482 | .052 | .044 | .032 |

| Observations | 265 | 5584 | 7355 | |||||||

This table provides summary statistics for the cross-listed ADRs, non-cross listed EM firms and US firms in the sample. A firm is defined cross-listed if it was continuously cross-listed in the US market for the period 2007–2014. All cross-listed and non-cross listed firms are publicly traded EM firms that are from Bloomberg's Best Emerging Markets 2014 list. Corporate governance include the following variables: Governance score, calculated by Bloomberg Professional database and is based on the extent of a company's governance disclosure, where the score ranges from 0.1 for companies that discloses minimum amount of governance data to maximum of 100. Board independence, measured by the number of independent directors on the board divided by the board size; Committees, measured by the number of committees (including audit, nomination and compensation committees) established in the company that ranges between 0 and 3; CEO duality, measured as a dummy variable coded as 1 if the CEO of the company also serves as the chairman of the board and 0 otherwise; Ethics policy, measured as a dummy variable coded as 1 if the company has a formal ethics policy and 0 otherwise; Risk taking is measured by Return volatility, estimated using the standard deviation of stock return over year t, requiring a minimum of 6 months for each year. Leverage, firm size and Tobin's Q are included as controls.

A comparison of the US sample with that of the ADRs and EMs reveals two of the relative strengths of the US corporate governance standards. On average US firms have almost double the percentage of independent directors and US firms are more likely to have a codified ethics policy than either their ADR or EM counterparts. Conversely, virtually half of the US CEOs in the sample also serve as Chairman of the Board, which is more than three times that of the CEOs of ADR firms and more than twice that of EM firms. The stock return volatility of the respective samples reveals that US firms typically are less risky than EM firms, but there appears to be no statistical difference between the riskiness of US firms and ADRs.

In general, the summary statistics indicate that there is a notable difference in the governance structure between US, ADR and EM firms. Moreover, the average values of the governance factors we employ in our analysis suggest that cross-listed ADR firms are more closely aligned with US best practices governance standards than non-cross listed EM firms.

Empirical modelIn this study we employ a two-step Generalized Least Squares (GLS) random effects model to capture both cross-sectional and time-series variation in the data. Prior to selecting the specific estimation technique a Woolridge test for autocorrelation (Drukker, 2003) revealed positive serial correlation between the dependent and independent variables. Consequently, a double transformation of the data was implemented to correct for the autocorrelation as well as potential heteroskedasticity problems using a two-step GLS procedure, in which the data is corrected for unobservable, firm-specific and time-invariant effects (Halaby, 2004; Mátyás and Sevestre, 2008).3 Also, we employ a variance inflation factor (VIF) test to determine that multicollinearity is not a problem in our models.

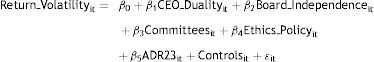

Two-step GLS random effects regression analyses are specified from a general model that represents stock return volatility, or corporate risk, as a function of various corporate governance indicators and control variables. In the first model, corporate risk is defined as a function of an overall governance disclosure score as in Eq. (1):

In the second model, each of four governance variables, plus an indicator variable for Level 2 or 3 ADRs are incorporated into the governance – risk regression model for each of the samples as in Eq. (2):

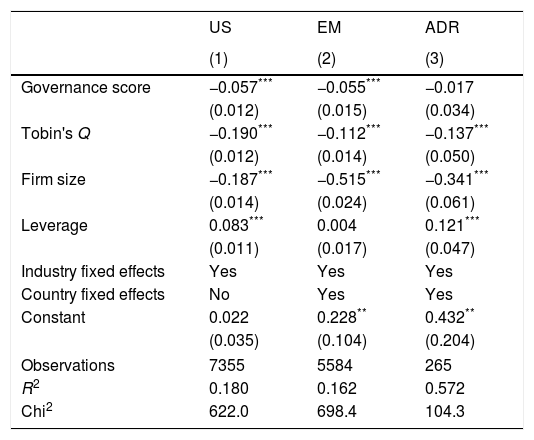

ResultsThe effect of governance on riskIn Table 4, Models 1 through 3 provide the estimates of the impact of the governance score on risk for US firms, EMs and ADRs, respectively. Models 1 and 2 show (i.e., US and EMs) that an increase in the governance score (βUS: −0.057 and βEM: −0.055; p<0.01) is likely to reduce risk for both US and EM firms, while the estimates for ADR firms in Model 3 reveals a negative, but statistically insignificant coefficient on the governance score.

Two-step GLS regressions of governance score on return volatility.

| US | EM | ADR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Governance score | −0.057*** | −0.055*** | −0.017 |

| (0.012) | (0.015) | (0.034) | |

| Tobin's Q | −0.190*** | −0.112*** | −0.137*** |

| (0.012) | (0.014) | (0.050) | |

| Firm size | −0.187*** | −0.515*** | −0.341*** |

| (0.014) | (0.024) | (0.061) | |

| Leverage | 0.083*** | 0.004 | 0.121*** |

| (0.011) | (0.017) | (0.047) | |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country fixed effects | No | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.022 | 0.228** | 0.432** |

| (0.035) | (0.104) | (0.204) | |

| Observations | 7355 | 5584 | 265 |

| R2 | 0.180 | 0.162 | 0.572 |

| Chi2 | 622.0 | 698.4 | 104.3 |

This table shows the outcomes of cross-sectional time-series two-step GLS regressions of return volatility on the governance score and control variables. It reports the standardized coefficients on the independent variables as well as standard errors in parentheses. All variable definitions are the same as in previous tables.

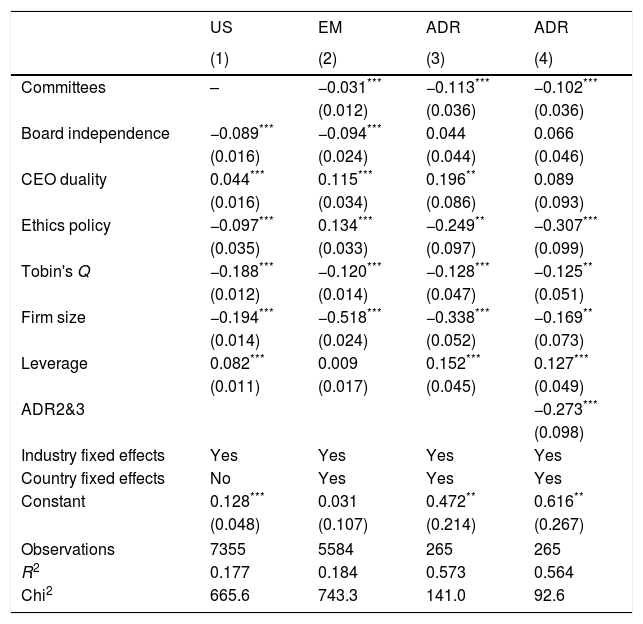

In Table 5, Models 1 through 3 provide the estimates of the corporate governance variables on risk for US, EM and ADR firms, respectively, while Model 4 includes a variable that captures the incremental impact of level 2 and level 3 ADRs on risk. The “Committees” variable is dropped from the US model because, as of 2003, the Securities Exchange Commission mandates that all US companies must have at least three committees. Used as a benchmark for the ADR and EM samples, Model 1 (US) indicates that, among firms in the US, an increase in board independence (β: −0.089; p<0.01) and the existence of an established ethics policy (β: −0.097; p<0.01) lead to a reduction in risk as measured by stock return volatility, while an increase in the occurrence of CEO duality (β: 0.044; p<0.01) appears to increase risk. Similarly, Models 2 and 3 reveal that CEO duality is positively related to risk for EM firms (β: 0.115; p<0.01) and so for ADRs (β: 0.196; p<0.05).

Two-step GLS regressions of governance factors on return volatility.

| US | EM | ADR | ADR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Committees | – | −0.031*** | −0.113*** | −0.102*** |

| (0.012) | (0.036) | (0.036) | ||

| Board independence | −0.089*** | −0.094*** | 0.044 | 0.066 |

| (0.016) | (0.024) | (0.044) | (0.046) | |

| CEO duality | 0.044*** | 0.115*** | 0.196** | 0.089 |

| (0.016) | (0.034) | (0.086) | (0.093) | |

| Ethics policy | −0.097*** | 0.134*** | −0.249** | −0.307*** |

| (0.035) | (0.033) | (0.097) | (0.099) | |

| Tobin's Q | −0.188*** | −0.120*** | −0.128*** | −0.125** |

| (0.012) | (0.014) | (0.047) | (0.051) | |

| Firm size | −0.194*** | −0.518*** | −0.338*** | −0.169** |

| (0.014) | (0.024) | (0.052) | (0.073) | |

| Leverage | 0.082*** | 0.009 | 0.152*** | 0.127*** |

| (0.011) | (0.017) | (0.045) | (0.049) | |

| ADR2&3 | −0.273*** | |||

| (0.098) | ||||

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country fixed effects | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.128*** | 0.031 | 0.472** | 0.616** |

| (0.048) | (0.107) | (0.214) | (0.267) | |

| Observations | 7355 | 5584 | 265 | 265 |

| R2 | 0.177 | 0.184 | 0.573 | 0.564 |

| Chi2 | 665.6 | 743.3 | 141.0 | 92.6 |

This table shows the outcomes of cross-sectional time-series two-step GLS regressions of return volatility on the corporate governance and control variables. It reports the standardized coefficients on the independent variables as well as standard errors in parentheses. All variable definitions are the same as in previous tables.

Consistent with the SEC's emphasis on establishing supportive committees as well as the findings in the extant literature, the results in Table 5 indicate that an increase in the number of committees significantly mitigates the riskiness of both cross listed ADR firms (β: −0.113; p<0.01) and non-cross listed EM firms (β: −0.031; p<0.01). Also, the existence of an ethics policy appears to decrease risk (β: −0.249; p<0.05) among ADR firms, while an increase in board independence mitigates risk (β: −0.094; p<0.01) among EM firms.

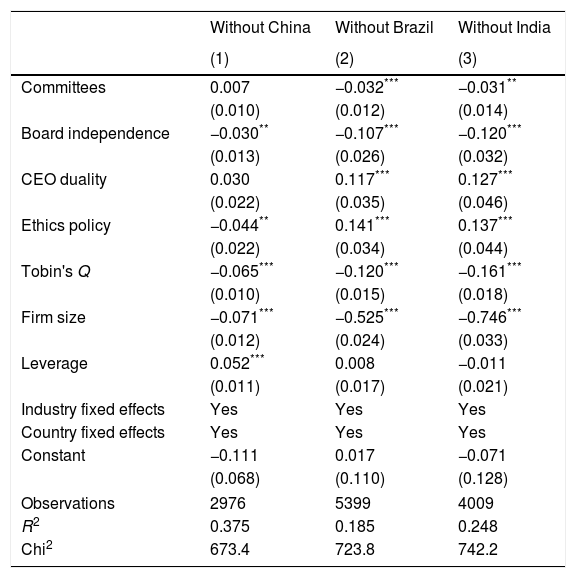

Surprisingly, unlike the sample of US (Model 1) and ADR (Model 3) firms, the results suggest that an established ethics policy leads to an increase in risk among the EM (Model 2) firms. To address this counter-intuitive outcome, the EM regressions presented in Table 5 are re-estimated after excluding each of the three countries that contribute the largest share of firms in the data – Brazil, China and India. The results of these sub-group regressions are presented in Table 6 and reveal that the positive relation between ethics and risk is primarily attributable to China.

Two-step GLS regressions of governance factors on return volatility – reduced sample.

| Without China | Without Brazil | Without India | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Committees | 0.007 | −0.032*** | −0.031** |

| (0.010) | (0.012) | (0.014) | |

| Board independence | −0.030** | −0.107*** | −0.120*** |

| (0.013) | (0.026) | (0.032) | |

| CEO duality | 0.030 | 0.117*** | 0.127*** |

| (0.022) | (0.035) | (0.046) | |

| Ethics policy | −0.044** | 0.141*** | 0.137*** |

| (0.022) | (0.034) | (0.044) | |

| Tobin's Q | −0.065*** | −0.120*** | −0.161*** |

| (0.010) | (0.015) | (0.018) | |

| Firm size | −0.071*** | −0.525*** | −0.746*** |

| (0.012) | (0.024) | (0.033) | |

| Leverage | 0.052*** | 0.008 | −0.011 |

| (0.011) | (0.017) | (0.021) | |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −0.111 | 0.017 | −0.071 |

| (0.068) | (0.110) | (0.128) | |

| Observations | 2976 | 5399 | 4009 |

| R2 | 0.375 | 0.185 | 0.248 |

| Chi2 | 673.4 | 723.8 | 742.2 |

This table shows the outcomes of reduced samples excluding China, Brazil and India from the EM sample and reports the cross-sectional time-series two-step GLS regressions of return volatility on the corporate governance and control variables. It reports the standardized coefficients on the independent variables as well as standard errors in parentheses. All variable definitions are the same as in previous tables.

The estimation results of Model 4 in Table 5 indicate that level 2 and level 3 ADR firms exhibit statistically less risk (β: −0.273; p<0.01) than their level 1 counterparts, which points to the impact of the relatively stringent SEC mandated governance regulations relative to the level 1 ADRs. Overall, the evidence indicates that cross-listed ADR firms and non-cross listed EM firms reduced risk to an extent similar to that of US firms as a result of the SEC (2003) governance requirements. Therefore, the results support Hypotheses 1 and 2 with regard to the EM firms only. Hypothesis 3, however, is supported by the results of both the cross-listed ADR firms and non-cross listed EM firms. Hypothesis 4 is confirmed by the results relating to ADR firms alone, while Hypothesis 5 finds support among both the cross-listed ADR firms and the non-cross listed EM firms. Finally, Hypothesis 6 is confirmed by the results of cross-list ADRs.

Robustness checksTo address potential endogeneity between the corporate governance variables and risk, we employ a Durbin Wu Hausman (DWH) test (a.k.a. augmented regression test) to determine whether it is necessary to apply an instrumental variable in equations 1 and 2 (Davidson and MacKinnon, 1993). The results of the test indicate that the set of estimates obtained from the original GLS model is consistent and that endogeneity is not a serious problem for our model of the governance – risk relation.4

To examine the sensitivity of our results to country specific effects, we re-estimate the EM model 2 in Table 5 by excluding each of the three countries that comprise the largest portion of the EM data: China, Brazil and India. Provided in Table 6, the results show that both the sign and the statistical significance of the parameter estimates remain similar with regard to the governance-risk relation when either Brazil or India are excluded from the sample. When China is excluded from the sample, however, the variables representing “the number of committees” and “CEO duality” become statistically insignificant, while “ethics policy” produces a negative and statistically significant impact on risk. An important interpretation of this result is that while the only corporate governance factor that reduces risk across all of the EM countries is “board independence”, an established ethic policy mitigates risk in all of the emerging markets except China.

Finally, we assess the robustness of the governance-risk models with regard to our measure of risk by substituting the sum of squared residuals of the market model for the standard deviation of raw returns (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., 2006; Bargeron et al., 2010; Bhojraj and Sengupta, 2003; Brown and Kapadia, 2007; Campbell et al., 2001; McGuire et al., 1988). The results of the substitution indicate that, although the signs of the relation between the governance variables and risk do not change, overall the significance of the parameter estimates drops considerably.5

Generally, with the exception of the variations observed in the reduced sample excluding China from the EM sample, the sensitivity analyses reveal that the results of the study are robust to alternative methodological treatments.

Discussion and conclusionTheoretical ImplicationsIn this study, we investigate the effect of a governance disclosure score as well as specific governance standards on corporate risk, measured as the annualized standard deviation of weekly stock returns, in the post-SOX era. The primary focus of the study is on both cross-listed EM firms that are subjected to SEC mandated regulations through the issuance of an American Depository Receipt (ADR), and non-cross-listed EM firms that do not face the same regulatory constraints. The study offers several contributions to the theory of international corporate governance.

In line with Hypothesis 1, the results show that a higher governance score is associated with lower risk among non-cross listed EM firms, while there appears to be no relation between the governance score and the riskiness of cross-listed ADR firms. Also, the results indicate that governance rules that are mandatory for US firms whose equities trade on the NYSE or NASDAQ effectively discourage risk-taking among ADR firms. Similar to Litvak (2007a, 2007b), who reports a reduction in the stock prices of both cross-listed and non-cross-listed firms after the passage of SOX (2002), we find a reduction in the riskiness of cross-listed firms (more significantly for level 2 and 3 ADRs) and non-cross-listed EM firms during the post-SOX era years, 2008–2014. In this context, agency theory predicts that by strengthening the monitoring and control mechanisms between the owners and top management, firms are effectively motivated to reduce corporate risk (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Furthermore, bonding theory suggests by adopting the U.S. “best practice” governance rules, firms in the emerging markets are more closely aligned with evolving global standards and thereby mitigate risk-taking behavior (Coffee, 1999). Consequently, our results support the notion that, in order to attract investors and remain competitive in the global market, emerging market firms voluntarily implement the “best practice” governance standards that have been established in the US. However, the results deviate within EM firms across the four governance standards. Specifically, in accordance with the governance literature, we find that only the variable representing the number of Independent Directors” is consistently, statistically related to an observed reduction in risk among EM firms (Beasley, 1996; Cotter and Silvester, 2003; Fields and Keys, 2003; Finkelstein and Hambrick, 1988), while an established ethics policy mitigates risk in all but the Chinese market.

The coefficient estimates of the Chinese firms deviate significantly from the rest of the developing world with regard to the impact of the three of the variables: Number of Committees, CEO Duality and the existence of an established Ethics Policy – the prior two with regard to statistical significance and the latter in sign. In agreement with previous research, increasing the number of committees assisting the board in its oversight and restricting duality of the CEO's role (i.e., as chairman of the board and chief operating officer) appear to effectively strengthen the governance structure of Chinese companies, thereby mitigating risk (Cohen et al., 2010; Conyon and Peck, 1998; DeZoort et al., 2008; Imhoff, 2003; Li and Tang, 2010). The efficacy of these two standards among firms operating in the emerging markets, however, remains ambiguous. Table 5 presents evidence that a formalized ethics policy is positively associated with risk in the emerging markets, however, when Chinese firms are excluded from the sample (Table 6) ethics policies are negatively associated with risk. As we would expect, this suggests that ethics policies typically are forged in the emerging markets to combat dysfunctional behavior and reduce the risk associated with stock price volatility (Orlitzky and Benjamin, 2001). In this context, such behaviors include bribery, denial of responsibility, unethical exercise of control, and biased performance evaluations (Boutin-Dufresne and Savaria, 2004; Simpson and Taylor, 2013).

One explanation for the unexpected positive association between “Ethics Policy” and risk among Chinese firms is that many of these firms employ an ethics policy as window dressing rather than as an effective rule governing the corporate culture. Lu (2009) provides two stark examples in the Chinese biotechnology industry. An Ying Biotechnological Development Company and Futian Biotechnological Company illegally produced and then exported contaminated pet food that caused serious health problems in the animals that consumed them. Ironically, each of these companies had previously been awarded “Honesty and Trustworthy Enterprise” honors by government authorities In another study, Baskin (2006) investigates the extent to which ethics management systems are developed in the emerging markets and argues that China provides the least evidence of addressing the business ethics issue. Furthermore, the Western concept of ethics may not apply to China because of specific cultural differences and the impact Confucianism, and its almost codified respect for authority and loyalty, has on employee behavior and the willingness to report misdeeds (Irwin, 2012). Finally, although governance rules require Chinese companies to establish an ethics policy, these companies often lack the management system to ensure that these policies are viable (Chen et al., 2006).

Our findings extend the current literature in that they provide evidence that SOX (2002) mitigates risk in the level 2 and 3 ADR firms by identifying specifically which of the corporate governance rules effectively diminish risk (Boubakri et al., 2010; Chira, 2014; Haripriya et al., 2006; Litvak, 2014). The ADR estimation results in Table 5 indicate that a greater number of committees and the presence of formal ethics policies have a mitigating effect on risk. Models 3 and 4 show that CEO duality, by weakening corporate governance mechanisms, reduces board-monitoring effectiveness and promotes risky behavior. As the indicator variable in Model 4 shows, however, this is only a characteristic of level 2 and level 3 ADRs, because of the increased SEC scrutiny and mandated reporting requirements on these firms. Interestingly, the independence of board members does not appear to affect the riskiness of ADRs, even though US firms that are subject to the same regulatory scrutiny do see a reduction in risk; and this is true after controlling for the level of the ADR.

Overall, with the exception of board independence, which affects US and EM firms but does not appear to affect ADRs, the riskiness of US, EM and ADR firms respond in a similar manner to the remaining three governance variables we examine in this study. Corresponding to both agency and bonding theory, the results suggest that in order to appeal to foreign investors and remain viable as potential international investments, firms in the emerging countries must abide by the “best practice” governance standards that are already effective in the US. Such efforts can lessen the possibility of conflict between the managers of the firm and its owners as well as reduce risk-taking activities (Coffee, 1999; Jensen and Meckling, 1976). In accordance with the extant literature, increasing the number of committees decreases risk and allowing the CEO to hold the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer positions simultaneously increases risk (Abdullah, 2006; Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., 2006). Generally, the results also support the notion that an established ethics policy reduces corporate risk; after removing China from the sample (Table 6) the riskiness of EM firms decreases in the presence of an ethics policy.

Managerial implicationsThis study contributes to the empirical literature through the application of a cross-sectional time-series analysis, allowing for the articulation of a governance-risk interaction across markets over a specific period of time and provides important practical implications for the practice of corporate governance in an international setting. The results indicate that separating the chief executive and chairman positions and forging more independent committees to support the board of directors (BOD) is important for reducing risks that might arise from an overly powerful CEO and a lack of oversight by the BOD (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., 2006; Imhoff, 2003; Jensen, 1993). Consequently, prudent corporate governance requires firms to manage and monitor the CEO's influence to allow the BOD and independent committees to fulfill their responsibilities to shareholders (Garrett, 2007; Tuggle et al., 2010). We also find that the promulgation of a formal ethics policy is an important element in establishing an effective corporate governance regime and mitigating dysfunctional behavior and unwarranted risk. Still, managers also should be mindful of the ethical challenges associated with doing business in China. Existing ethics policies do not appear to provide an adequate disincentive to risky behavior on the part of managers, but serve only as social and political cover for Chinese firms. To appropriately address the potential ethical conflicts that result in illegal activity, consumer mistreatment and investor mistrust, support in the form of more rigorous public policy aimed toward enhanced corporate governance will be required.

Emerging market firms have only recently begun to strengthen their corporate governance policies and, in general, lag behind the best practices laws and procedures applied in US markets (Claessens and Yurtoglu, 2013). Nonetheless, we present evidence in this paper that EM firms that apply the US governance standards mitigate risk and provide an element of protection to shareholders that heretofore did not exist in the emerging markets. Therefore, by voluntarily binding themselves to US corporate governance standards, EM firms can effectually indicate to global investors a willingness to offer protection from expropriation and a dedication to assuaging risk.

Limitations and future researchThe method employed in this paper can provide direction for future research in the emerging markets on the governance-risk relationship; yet, our investigation comprises a number of limitations. For example, because the time-series of EM data are incomplete, we could not investigate the effect of governance on corporate risk prior to the adoption of the SEC (2003) guidelines; these guidelines may have had a residual, positive impact on corporate governance practices among firms in the emerging markets. It could be fruitful to examine governance practices in the emerging markets during the early 2000s to verify a movement toward governance best practices during the years 2008 to 2014 – the relevant time frame of this paper.

Another data limitation relates to a lack of country specific information in the Bloomberg Database. Because data are either missing or unavailable, Chile, Columbia, India, Malaysia, Panama, Peru, the Philippines, Poland and Thailand were omitted from the ADR sample. Moreover, four of the 22 best performing EM countries as ranked by Bloomberg (i.e., the Czech Republic, Egypt, Latvia and Morocco) could not be included in the relevant sample, either because of a stock de-listing from the US market or because reliable, contiguous governance data were not available. Consequently, researchers might discover locally available governance data on these countries in an effort to extend the scope of our analysis.

The Chinese market bears additional scrutiny. Two of the governance (standards) variables analyzed in our sample, the Number of Committees and CEO Duality, produce a disparate impact on risk when China is included in the emerging markets sample. Moreover, the presence of a well-defined Ethics Policy appears to be associated with an increase in firm risk among Chinese firms. Accordingly, a potentially fruitful area of research could be based on an examination of Chinese firms in an effort to shed a clearer light on the seemingly peculiar relationship between corporate governance and risk in that unique market.

Finally, our study could be extended to include the United Kingdom (UK), a country that established a corporate governance code as early as 1992. Unlike the “regulator-led” corporate governance system in the US, the system in the UK is “shareholder-led”, which gives shareholders the authority to determine their own governance measures. A comparison of governance practices between firms in the UK and those in the emerging markets could provide additional evidence regarding the progress of these companies toward best practice governance standards of developed economies.

The authors are grateful for comments on an earlier draft from Bruce Resnick (Professor at WFU), Wayne Landsman (Professor at UNC-Chapel Hill) and Shivaram Rajgopal (Professor at Columbia University). This study was funded by Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey – TUBITAK (grant number: B.14.2.TBT.0.06.01-219-115543).

Please check European Corporate Governance Institute‘s website: http://www.ecgi.org/ to reach the index of all country codes.

Specifically, we applied the xtregar command in STATA along with the Durbin–Watson statistics and the random effects option. In a panel data structure, xtregar fits panel data regression models when the disturbance terms are first-order autoregressive and adjusts the unbalanced panels whose observations are unequally distributed over time. One benefit of using this tool resides in its ability to adjust unbalanced panels whose observations are unequally distributed over time. We further apply a two-step implementation of the rhomethod to more efficiently estimate p values.