Introduction and aim. Procalcitonin is widely used as a biomarker to distinguish bacterial infections from other etiologies of systemic inflammation. Little is known about its value in acute liver injury resulting from intoxication with paracetamol.

Material and methods. We performed a single-center retrospective analysis of the procalcitonin level, liver synthesis, liver cell damage and renal function of patients admitted with paracetamol-induced liver injury to a tertiary care children’s hospital. Children with acute liver failure due to other reasons without a bacterial or fungal infection served as the control group. Twelve patients with acute paracetamol intoxication and acute liver injury were compared with 29 patients with acute liver failure.

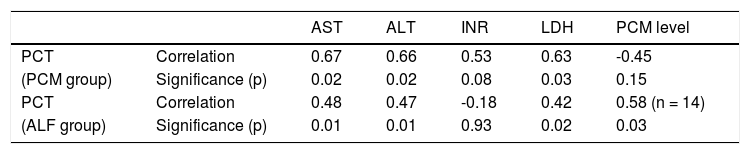

Results. The procalcitonin levels were higher in children with paracetamol intoxication than in patients with acute liver failure without paracetamol intoxication (median 24.8 (0.01-55.57) ng/mL vs. 1.36 (0.1-44.18) ng/mL; p < 0.005), although their liver and kidney functions were better and the liver cell injury was similar in both groups. Outcome analysis showed a trend towards better survival without transplantation in patients with paracetamol intoxication (10/12 vs. 15/29). Within each group, procalcitonin was significantly correlated with alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase but was not correlated with the International Normalized Ratio or paracetamol blood levels in the paracetamol group. In conclusion, paracetamol intoxication leads to a marked increase in procalcitonin serum levels, which are significantly higher than those seen in acute liver failure.

Conclusion. The underlying mechanism is neither caused by infection nor fully explained by liver cell death alone and remains to be determined.

Procalcitonin (PCT) is a prepeptide of calcitonin that is released under normal circumstances by thyroid C cells; blood levels in healthy subjects are almost undetectable.1,2 In the case of a systemic bacterial infection, PCT becomes a useful biomarker to identify septic children and titrate the length of antibiotic therapy.3–6 For example, neuroendocrine cells of the lungs, leukocytes and liver cells contribute to the elevated release of PCT. Although the exact mechanisms remain unclear, cytokine stimuli, such as interleukin 2 and tumor necrosis factor alpha, are thought to play an important role in mediating the increase in PCT.7,8

Furthermore, it has been shown that clinical states with systemic inflammation might also increase PCT, making it less ideal as a biomarker for bacterial infections.9–11 After open heart surgery, children who received a cardiopulmonary bypass had markedly elevated PCT levels in the absence of a bacterial infection.12 Additionally, those with higher blood levels had longer bypass times and intensive care unit (ICU) stays. Another study demonstrated the discriminative power of PCT in identifying critically ill children who were at a higher mortality risk, independent of the underlying infection.13

Elevated PCT levels were also detected in organ-specific diseases, especially concerning the liver. In patients with acute hepatitis, PCT is significantly higher when acute liver failure (ALF) is present;14 by contrast, in ALF, PCT is usually increased. In these patients, the PCT level is independent of the presence or absence of an underlying bacterial infection.15 Mallet, et al. showed that in patients with Paracetamol (PCM) intoxication PCT level cannot discriminate patients with and without infection, while its discriminative power was preserved in patients with ALF without PCM intoxication.16 Patients with lung cancer had higher PCT levels when liver metastases were present.17 In hepatocarcinoma, the PCT level correlates to the tumor size and survival.18 After partial liver resection, PCT is elevated after reperfusion and is considered to be a consequence of tissue hypoxia and postischemic inflammation.8 It is also known that after liver transplantation, children can have markedly elevated PCT, which is in this case, not an indicator of infection but an indicator of poor outcome.19,20

Because we had evidence from clinical experience of marked elevation in single cases of PCM intoxication without bacterial infections, we wanted to know whether this was a constant finding. As the main clinical feature in these children and adolescents is an acute liver cell injury, patients with acute liver failure resulting from other reasons without bacterial or fungal infections served as the control group. ALF in children is often life-threatening, and treatment might include vasopressor support, hemodialysis, and transplantation. The clinical picture can resemble a clinical state, such as septic shock. PCT was therefore assumed to be elevated.

Material and MethodsPatientsWe performed a retrospective single-center case series in children with an acute liver injury resulting from PCM intoxication or with ALF resulting from other causes. The children’s department of the University of Essen is a tertiary care center and serves as a referral center for pediatric liver transplantation. Patients were identified from 2009 to July 2016 by a computer-based search of Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRG) according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10, with K72.0 for acute and subacute liver failure and T39.1 for paracetamol intoxication. All patients were then reviewed by chart analysis and were included if they met the following inclusion criteria:

- •

International Normalized Ratio (INR) > 1.5 and presence of hepatic encephalopathy, INR > 2 or paracetamol induced liver injury.

- •

PCT was measured at least once within 24 h of admission.

- •

No underlying chronic liver disease except for Wilson’s disease; and

- •

No systemic or local bacterial or fungal infection present defined as the absence of Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) in the PCM group and a negative blood culture and/or other cultures obtained from sterile sites, such as ascites in the ALF group.

For all patients, demographic data (age, sex, and reason for ALF) and outcomes (discharged home or to a secondary institution, received liver transplantation, or died) were recorded. Laboratory data at admission were collected, including INR, Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), bilirubin, C-reactive protein (CRP), PCT, creatinine, PCM levels and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). In patients with PCM intoxication, we also documented the time since drug consumption and amount of drug taken.

All identified patients were divided into two groups: acute liver injury resulting from PCM intoxication (PCM group) and ALF due to other reasons (ALF group) as controls. A favorable outcome was defined as survival without liver transplantation.

StatisticsStatistical analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS Statistics 22. Data are presented as the medians, minimums, and maximums. Comparisons of two unrelated groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney-U test. Analysis of categorical variables was performed using the Chi-square test (χ2). Statistical dependence of two non-parametric variables was calculated by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

EthicsThe study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of the University Hospital of Essen (15-6558-BO).

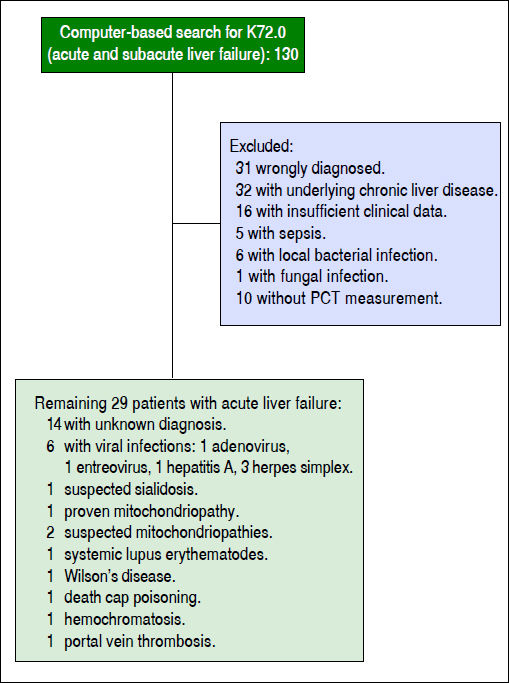

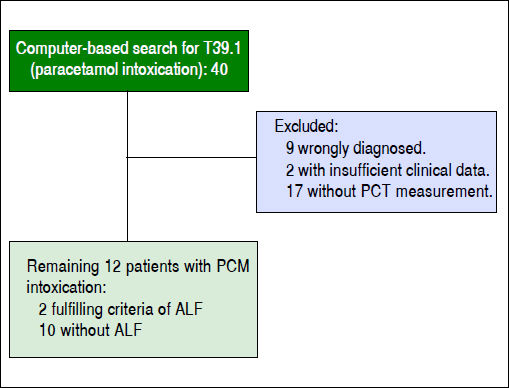

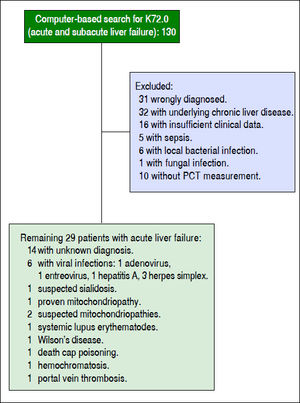

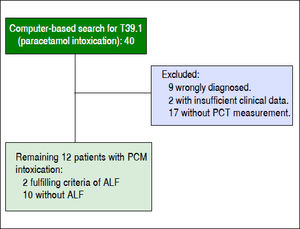

ResultsA computer-based search of DRG revealed 130 patients with ALF from 2009 to July 2016, excluding patients with PCM intoxication (ALF group). For inclusion and exclusion of patients (Figure 1). A search for PCM intoxication showed 40 patients. Of these patients, nine were misdiagnosed; in 17 children and adolescents, PCT was not measured; and in two children, data were incomplete (PCM group, Figure 2). Demographic data and the laboratory results of the patients are provided in table 1. In the ALV group, five patients had a slight elevation of serum creatinine levels, one patient presented with a severe kidney injury (creatinine 271 μmol/mL) compared to one patient with a slight elevation of creatinine in the PCM group. Creatinine was not correlated with PCT in either the ALV or PCM groups.

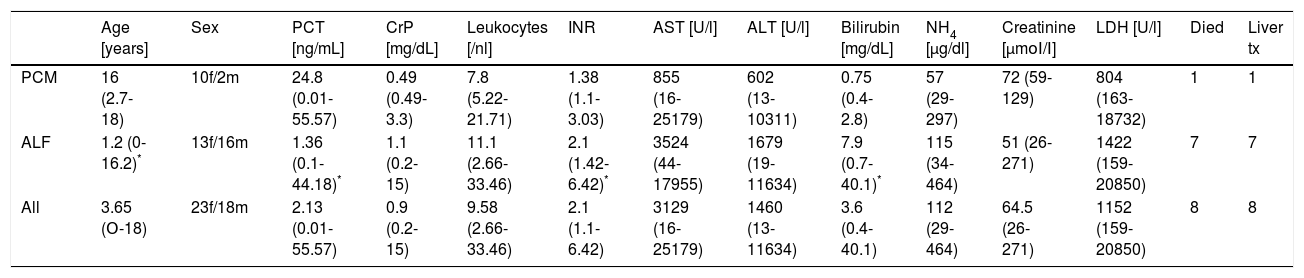

All patients with PCM intoxication showed a marked elevation of PCT serum levels except for two patients. Nine out of twelve patients in the PCM group had higher levels than 10 ng/mL compared to two out of 29 in the ALF group. Both patients had measurable PCM blood levels. In general, the markers of liver cell injury, such as AST, ALT, and LDH, were similar in both groups, but INR and bilirubin were higher in the ALF group (Table 1). Correlations between PCT and blood tests for liver injury and between PCT and PCM blood levels are given for both groups in table 3. Considering all patients, the AST and ALT levels were positively correlated with the PCT levels.

Comparison of children with paracetamol intoxication and children with acute liver failure resulting from other reasons.

| Age [years] | Sex | PCT [ng/mL] | CrP [mg/dL] | Leukocytes [/nl] | INR | AST [U/l] | ALT [U/l] | Bilirubin [mg/dL] | NH4 [μg/dl] | Creatinine [μmοΙ/Ι] | LDH [U/l] | Died | Liver tx | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCM | 16 (2.7-18) | 10f/2m | 24.8 (0.01-55.57) | 0.49 (0.49-3.3) | 7.8 (5.22-21.71) | 1.38 (1.1-3.03) | 855 (16-25179) | 602 (13-10311) | 0.75 (0.4-2.8) | 57 (29-297) | 72 (59-129) | 804 (163-18732) | 1 | 1 |

| ALF | 1.2 (0-16.2)* | 13f/16m | 1.36 (0.1-44.18)* | 1.1 (0.2-15) | 11.1 (2.66-33.46) | 2.1 (1.42-6.42)* | 3524 (44-17955) | 1679 (19-11634) | 7.9 (0.7-40.1)* | 115 (34-464) | 51 (26-271) | 1422 (159-20850) | 7 | 7 |

| All | 3.65 (Ο-18) | 23f/18m | 2.13 (0.01-55.57) | 0.9 (0.2-15) | 9.58 (2.66-33.46) | 2.1 (1.1-6.42) | 3129 (16-25179) | 1460 (13-11634) | 3.6 (0.4-40.1) | 112 (29-464) | 64.5 (26-271) | 1152 (159-20850) | 8 | 8 |

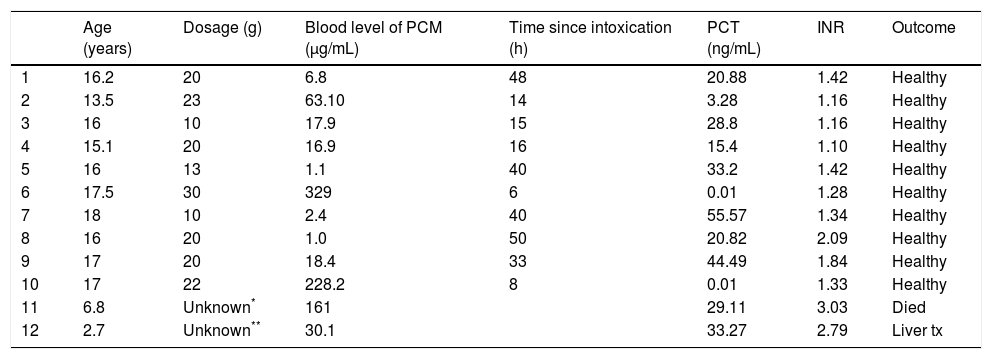

The two patients with the highest paracetamol blood levels in the PCM group had the lowest PCT levels and shortest time interval between drug intake and blood tests. One of the patients with a normal PCT level received three measurements in total as follow-ups; these were all normal. Acetylcysteine was started very early (six hours after intoxication of 20 g of paracetamol), and AST and ALT remained almost normal. The laboratory results and historical data of patients with PCM intoxication are given in table 2.

Characteristics of patients with paracetamol intoxication.

| Age (years) | Dosage (g) | Blood level of PCM (μg/mL) | Time since intoxication (h) | PCT (ng/mL) | INR | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16.2 | 20 | 6.8 | 48 | 20.88 | 1.42 | Healthy |

| 2 | 13.5 | 23 | 63.10 | 14 | 3.28 | 1.16 | Healthy |

| 3 | 16 | 10 | 17.9 | 15 | 28.8 | 1.16 | Healthy |

| 4 | 15.1 | 20 | 16.9 | 16 | 15.4 | 1.10 | Healthy |

| 5 | 16 | 13 | 1.1 | 40 | 33.2 | 1.42 | Healthy |

| 6 | 17.5 | 30 | 329 | 6 | 0.01 | 1.28 | Healthy |

| 7 | 18 | 10 | 2.4 | 40 | 55.57 | 1.34 | Healthy |

| 8 | 16 | 20 | 1.0 | 50 | 20.82 | 2.09 | Healthy |

| 9 | 17 | 20 | 18.4 | 33 | 44.49 | 1.84 | Healthy |

| 10 | 17 | 22 | 228.2 | 8 | 0.01 | 1.33 | Healthy |

| 11 | 6.8 | Unknown* | 161 | 29.11 | 3.03 | Died | |

| 12 | 2.7 | Unknown** | 30.1 | 33.27 | 2.79 | Liver tx |

In 14 patients with acute liver failure, the PCM blood levels were measured. Of those, seven had detectable but low PCM levels. Within this group, patients with detectable PCM blood levels had significantly higher PCT levels (6.30 ng/mL vs. 1.54 ng/mL; p < 0.05) than those with negative results, but there were no differences in CRP, INR, AST, ALT, NH4, bilirubin, LDH, age or creatinine.

Considering all patients, there was no statistical difference in PCT between patients who had complete liver function recovery compared to those who died or received a liver transplantation. In the ALF group alone, PCT was significantly higher in children with a good outcome. Patients with a favorable outcome had a PCT of 1.71 (0.1-44.18) compared to 1.03 (0.2-6.27) in patients who died or received a liver transplantation (p < 0.05). This difference was not observed in patients with PCM intoxication. Those with a good outcome had a PCT of 20.88 (0.01-55.57) ng/mL compared to 29.11 ng/mL in the patient who received a liver transplantation and 33.27 ng/ mL in the patient who died.

DiscussionThis retrospective case series revealed a marked elevation of serum PCT levels in patients with drug-induced liver injury because of paracetamol intoxication. The values of PCT peaked at unusually high levels; under normal circumstances, this would indicate a bacterial infection with high predictive probability. The PCT levels observed in our patients exceeded those measured in some children with septic shock.4 Similar results have been published very recently in adults and in an abstract in the year 2000, but these data were not found in a Medline search.15,21 For the first time, it was shown that the rise in PCT can be partly explained by cell death because there was a positive correlation between AST, ALT, and PCT. However, sicker patients in the ALF group with a lower tendency to recover had significantly lower PCT levels. If liver cell injury was the key to PCT elevation, one would expect the opposite, that is, higher values in patients with acute liver failure.

It has been previously shown that PCT elevation also occurred in patients without infection, e g., in patients with severe inflammation after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery.12 Sterile inflammation was assumed to enhance PCT in migraine patients.22 Liver involvement, e.g., as a result of metastases, also led to elevated PCT levels.17 Compared to the findings in our patients with PCM intoxication, these PCT levels were, on average, 10-100 times lower. Similarly, high levels without infection were only observed in children after liver transplantation, and these high levels were associated with a poor organ outcome.19,20 Because the PCT values did not indicate a poor prognosis in our patients, we suggest a different mechanism of PCT elevation related to PCM intoxication. Following liver transplantation, PCT elevation might be correlated with severe systemic inflammation, as indicated by high blood lactate, vasopressor support, and high fluid throughput. By contrast, our PCM patients were mostly clinically stable, and bacterial infection was ruled out as well.

Interestingly, we also found significantly higher PCT levels in patients without PCM intoxication who had a detectable PCM blood level compared to those who had an undetectable PCM blood level. The consequences of these findings remain speculative, but it has to be discussed whether PCM plays a role in elevating PCT serum values even without intoxication. Only two patients with PCM intoxication showed a negative PCT serum level. Different from all other patients, these levels were measured very early (six and eight hours after PCM intoxication), suggesting that PCT release starts later. This finding would parallel the PCT release during a systemic bacterial infection in which the high PCT peak occurs approximately 12 h after infection. Additionally, one could also suggest that the missed PCT increase in the patient who received serial measurements was suppressed by an early start of acetylcysteine treatment.

What might be the reason for the relationship between PCM intoxication and the marked PCT increase? In PCM intoxication, hepatocyte damage initiates an innate immune response, mediating repair mechanisms that are different from repair mechanisms, e.g., in acute viral infections.23 It has been well described that in PCM-induced liver damage, hepatocytes release damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that induce inflammasomes and inflammation in the liver.24 This sterile inflammation is mainly induced by the cytokines IL-1 beta and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha. Because PCT is a marker of the inflammatory response of the innate immune system, this might at least partly explain the high levels of PCT in PCM-induced liver damage. Another reason could be the otherwise unnoticed involvement of different organs in PCT release, such as endothelial cells. However, it has to be stated that the discussed pathophysiological mechanisms for the correlation of PCM intoxication and PCT elevation remain highly speculative. Interestingly, the two youngest patients with PCM intoxication developed ALF. In general, PCM-induced hepatotoxicity is lower in younger patients, most likely because of the larger cell mass in these patients.25 The described two patients suffered from underlying diseases (one osteogenesis imperfecta and one psychomotor retardation of unknown origin) that could have influenced hepatotoxicity, e.g., the nutritional status.25

PCM is a widely used drug in pediatrics that is used to fight fever and pain. Pediatricians have experience with this drug worldwide. Weak concerns have been raised in the past that the drug might contribute to increased cardiovascular events, such as heart attack and stroke. Chan, et al. found an increased incidence in frequent users of PCM.26 Additionally, it has been recently shown that at least intravenous administration of PCM leads to a decrease in blood pressure.27 In light of these results and in accordance with our data regarding PCT elevation, the question of negative side effects of PCM in non-toxic doses has to be addressed. The other question that arises from our case series is related to the diagnostic value of PCT for bacterial infection in patients with a history of (repeated) PCM intake. Our data suggest that this topic should be addressed in further studies.

Our study has certain limitations. First, it is a retrospective case study with known limitations. Some important data are lacking, e.g., repetitive and standardized PCT measurements. Additionally, in general, the study group sample size is small and has great heterogeneity concerning the underlying diagnosis of ALF as well as the age distribution. Newborns were assessed together with adolescents.

ConclusionIn our study population, PCT was consistently and markedly elevated in children and adolescents with PCM intoxication and could not be explained by a bacterial infection or liver cell injury alone. To learn more about the relationship between PCM-induced liver injury and its effect on PCT levels, future prospective trials are needed.

Abbreviations- •

ALF:acute liver failure.

- •

ALT:alanine aminotransferase.

- •

AST:aspartate aminotransferase.

- •

CRP: C-Reactive Protein.

- •

DAMP: Damage Associated Molecular Patterns.

- •

DRG: Diagnosis Related Group.

- •

ICD: International Classification of Diseases.

- •

ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

- •

INR: International Normalized Ratio.

- •

LDH: lactate dehydrogenase.

- •

PCM: paracetamol.

- •

PCT: procalcitonin.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. There was no source of funding for this study.