Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans (TMEP) was first described by Parker in 1930.1 It is a form of cutaneous mastocytosis, and is differentiated from other forms such as urticaria pigmentosa, solitary mastocytoma, and diffuse or systemic mastocytosis by its refractory nature and/or lack of systemic associations. All forms have in common excessive accumulation of mast cells, whether localised to the skin or generalised to involve internal organs.

Although TMEP typically occurs in adults, a few cases have been reported in children.2 It may rarely be inherited. Chang et al. reported a case of TMEP affecting members of three generations, with onset during childhood, supporting the hypothesis of an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance.3 Clinically, TMEP presents with cutaneous telangiectasia as the most important feature. Clinical presentation consists of red telangiectactic macules, with subtle and discrete papules and accompanying hyperpigmentation. Darier's sign, which is urtication after rubbing, is usually negative in patients with TMEP as opposed to other forms of mastocytosis in which it occurs. Lesions typically involve the trunk and extremities, and facial involvement is rare.4,5

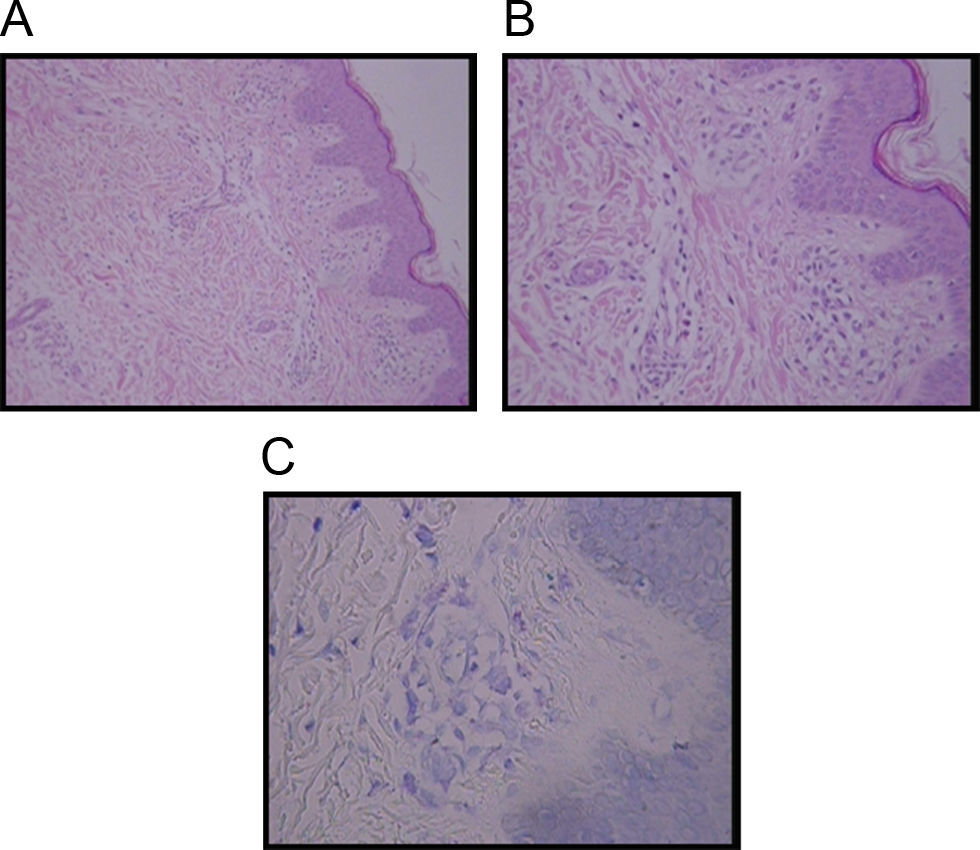

Diagnosis of TMEP is confirmed by skin biopsy with the finding of spindle-shaped mast cells. Special stains such as Giemsa stain, Toludine blue, and Leders stain highlight mast cells typically in the upper third of the dermis and around capillaries. The presence of more than 5–10 mast cells per high-power field in Giemsa or Toludine blue-stained tissue sections is considered abnormal, thus confirming the diagnosis3,6 (Figure 1).

Generally the lesions are refractory to treatment. Different treatment modalities are used according to clinical findings. We report a 4.5 year old boy with TMEP in whom a good clinical response was achieved by administration of montelukast.

A boy was first seen at the age of 6 months (Figure 2) with a history of pruritic erythematous macules on his trunk and extremities. Darier's sign was negative. The diagnosis was TMEP with the clinical findings and skin biopsy. Laboratory tests and physical examination revealed no systemic involvement. Antihistamine treatment was given. Eighteen months later, he still had pruritus and needed supplementary high doses of antihistamine in addition to regular doses. At 2 years of age, we added montelukast 4mg per day to treatment. We were able to stop the regularly used antihistamine 2 months later. The patient is 4.5 years old now, and uses the montelukast without almost any new lesions and pruritus or side effects. He rarely needs antihistamine. The pictures below show the lesions every two years (Figures 2 and 3) and the skin biopsy microscopic appearance in the first visit (Figure 1).

TMEP is a form of cutaneous mastocytosis. Other forms include solitary mastocytoma and urticaria pigmentosa. The course of TMEP appears to be benign but is uncertain as so few cases have been reported and long term follow-up is lacking. Some serious systemic disorders such as myeloproliferative disorders, multiple myeloma and renal carcinoma have been reported in association with TMEP in adult patients.7–9 Since TMEP is a rare diagnosis in paediatric population the discussion of treatment is limited mostly to the numerous cases in adults which have a wide spectrum of severity. Currently no cure exists for mastocytosis but some cases may be self limited. The main goal of therapy is relief of symptoms and antihistamines are often beneficial. Patients are educated to avoid stimuli that increase mast cells and the release of histamine including shellfish, alcohol, aspirin, envenomation by insects, and physical triggers such as pressure. In severe cases both H1 and H2 histamine receptor antagonists such as hydroxyzine, doxepine and cimetidine may help with pruritus, flushing and gastrointestinal symptoms. Oral disodium cromoglycate may also ameliorate gastrointestinal complaints. Psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) may be of benefit, but its use on both adults and children is usually reserved for those with severe disease.10 Flashlamp pumped dye laser therapy has been used successfully for cosmetic improvement in a few cases.5 Other treatment options include systemic and local corticosteroids as well as topical, intralesional and systemic interferon.

Cysteinyl leukotrienes (Cys-LTs) are potent proinflammatory mediators derived from arachidonic acid through the 5-lypoxigenase (5-LO) pathway. They exert important pharmacological effects by interaction with at least two different receptors: Cys-LT1 and Cys-LT2. By competitive binding to the Cys-LT1 receptor, leukotriene receptor antagonist drugs such as montelukast, zafirlukast, and pranlukast, block the effects of Cys-LTs and alleviate the symptoms of many chronic diseases, especially bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis. Mast cells produce and release a broad spectrum of mediators, including vasoactive amines; products of arachidonic acid metabolism; and many proinflammatory, chemoattractive, and immunomodulatory cytokines. CysLT1 inhibitor MK571 and FLAP inhibitor MK886 decreased IL-5 and TNFα production after FcεRI stimulation, implying autocrine signalling by cysteinyl leukotrienes in mast cells. Although no reported measurements of leukotrienes in patients with mastocytosis between or during clinical flares are available, anecdotal reports suggest a transient response to leukotriene antagonists used to treat recalcitrant symptoms. Symptomatic relief has been observed within the first month of treatment but tends to wane thereafter. The role of leukotriene receptor antagonists in TMEP has not been evaluated before. In our patient montelukast has resulted in an abrupt relief of symptoms.

In conclusion, the long term prognosis of TMEP is unknown because reported follow-up information of childhood cases is lacking. Currently, no curative therapy exists. Because it is an infrequent disorder, controlled studies evaluating efficacy of treatment modalities cannot be carried out and treatment is usually based on data evolving from case reports. To the best of our knowledge this is the first TMEP case to be treated with montelukast. We have achieved an abrupt and persistent clinical response through the use of montelukast. However, to establish its role in TMEP and identify the pathogenetic mechanisms involved, more studies need to be implemented. We conclude that a trial of leukotriene receptor antagonist drugs should be considered in patients with TMEP.