Although it has been hypothised that infections may play a preventive role in allergic diseases, the role of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is not clear. In this study we aimed to determine the association between H. pylori infection and allergic inflammation.

MethodsH. pylori infection was assessed in gastric mucosa tissue by microscopy. Skin prick tests (SPT) were performed with a battery of common inhalant and certain food allergens. Serum samples were tested for total immunglobulin E (T.IgE). Predictive factors for H. pylori infection and atopy were examined by a questionnaire.

ResultsA total of 90 subjects suffering dyspeptic symptoms were enrolled into the study. SPT positivity was similar between H. pylori (+) and H. pylori (−) subjects. Among the possible factors examined: age; gender; educational status; pet at home; BMI, family size; number of children and siblings; monthly income; drinking water source; smoking; and serum T.IgE levels were not related with H. pylori infection. However, perennial allergic symptoms were significantly higher in the H. pylori (−) group, seasonal allergic symptoms were related with an increased risk for H. pylori infection.

ConclusionsIn this sample group from a developing country H. pylori infection was not shown to be associated with atopic diseases. Therefore, the eradication of H. pylori may not be assumed to have an effect on allergic inflammation.

The prevalence of atopic diseases has increased dramatically in developed countries during the last decades.1 Among various plausible factors, the so-called 'hygiene hypothesis' has gained a big interest which refers to improved hygiene leading to a decreased stimulation of the immune system by infections.2 This has led to an immunodeviation with T helper 2 (Th2) enhancing effects followed by increased immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated allergy. In studies, some microorganisms have importance in the progression of atopy, acting like a marker for the environmental conditions by their frequent prevalence and early accusation time.3–8

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) causes a chronic bacterial infection that is usually acquired in early childhood and then persists throughout life. Due to its transmission pathway, poor hygiene seems to be a risk factor for H. pylori infection in contrast to atopic status.9 Although a negative association of oro-faecally spreaded infection with serological markers of sensitization and allergic disease has been reported, there is conflicting evidence concerning the specific role of this infection contracted during childhood. Therefore, H. pylori can either trigger an allergic inflammation,10–14 or play a protective role on atopy4–6,8, or have no effect.7,15,16

The 'hygiene hypothesis' seems to fit mainly with respiratory allergic diseases, as its effect was thoroughly investigated in asthma and allergic rhinitis.6,8 However, there is conflicting evidence concerning the relation between this hypothesis and atopic skin diseases and/or food allergy.10–15 Gastrointestinal flora is a barrier against food allergens. Inflammation developed as a result of H. pylori gastritis damages the integrity of the barrier, resulting in increased mucosal permeability and the transition of food allergens lead to allergic sensitization.10–12 Thus, the aim of the present study was to assess the association between H.Pylori infection and allergy and also to determine the role of common risk factors for both H. pylori and atopy.

MATERIALS AND METHODParticipants were recruited among the outpatients who attended Kirikkale University Hospital. A total of 90 subjects suffering dyspeptic symptoms were enrolled into the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a history of gastric complaints including dyspepsia, gastric pain, emesis, (2) exclusion of chronic systemic diseases or parasitic infections, (3) no prior H. pylori eradication therapy. A positive history of allergic diseases were not specifically accepted as an exclusion criteria.

Demographic data of the study group was collected. Asthma diagnosis was accepted if previously diagnosed by a doctor or at least 200 ml (12 %) reversibility was detected in FEV1. Rhinitis was diagnosed if at least two of the symptoms: rhinorrhoea, sneezing, itching or anosmia existed. Patients with urticaria were recruited if an acute attack was reported during the last two years. Food allergy was suspected if food related symptoms were reported.

Diagnosis of H. pyloriUpper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed. A local anaesthetic was applied as a spray in the throat approximately 5 min before the process was started. The endoscope was introduced orally and monitored on screen by the gastroenterologist. Biopsy specimens were taken from the gastric corpus or antrum mucosa (3–4 mm in size). Biopsy materials were fixed in 10 % formalin solution and embedded in paraffin following 6h of fixation and routine tissues process. Paraffin blocks were cut into 4-5um sections and stained with haematoxylin-eosin (H&E). The epithelium and lamina propria were examined for the H.pylori bacterium with × 10, × 20, × 40 magnifications by microscopy.

Skin prick tests (SPT)All patients underwent SPT with a battery of common inhalant and certain food allergens (Allergopharma, Reinbek, Germany). Histamine hydrochloride 10 mg/mL and phenolated glycerol-saline served as positive and negative controls. The results were recorded as the largest diameters in millimetres (mm) after 20 minutes and a wheal 3 mm greater than the negative control was considered to be a positive reaction. Atopy was defined as a positive result in SPT to at least one allergen. Serum samples were tested for total IgE (T. IgE) (Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay 'ECLIA', Roche, USA).

Possible risk factors for the development of H. pylori infection and atopy were evaluated by a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire inquired about: smoking habit (never smoked/active or ex-smoker); education level; working situation (active/unemployed); monthly income; home heating; presence of pet at home; drinking water source; number of children and siblings; and overall number of people living together. The duration (in years), and time (seasonal/perennial) of gastric and allergic symptoms were also investigated. If the symptoms occurred all year long, it was classified as perennial; if they occurred only in spring-summer time, it was classified as seasonal.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kirikkale University Hospital and all patients gave their informed consent.

Statistical analysisIntergroup comparisons were made using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative variables. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The association between each study factor and H. pylori infection and/or atopy was estimated by odds ratio formed by logistic regression analysis by adjusting cofounding variables (age, gender, BMI, smoking, education, monthly income). All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software package SPSS (11.0).

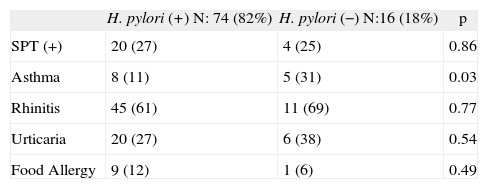

RESULTSPatients were aged between 17–74 years (mean: 38 ± 11 yr) with a female dominance (72 %). H. pylori infection was found to be positive in 74 (83 %) subjects. Atopic status was confirmed by positive SPTs in 24 (27%) patients and rhinitis was diagnosed in 62%, urticaria in 29%, asthma in 14%, and food allergy in 11% of the study population. The prevalence of H.pylori infection was similar between the atopic and non-atopic patients (83% v 81). Respiratory allergy (asthma and rhinitis) was significantly higher among the atopic group, whereas there was no difference regarding urticaria or food allergy (results not shown). Atopy prevalence was not significantly different between the H. pylori (+) and (−) groups (27% v 25%), as shown in Table I. Although the diagnosis of asthma was significantly higher in the H. pylori (−) group, the effect of asthma was insignificantly related to a lower risk of H. pylori infection (adjusted OR 1.0; 95% CI 0.1 to 18.9). There were no independent effects of rhinitis, urticaria or food allergy in terms of H. pylori infection (p > 0.05).

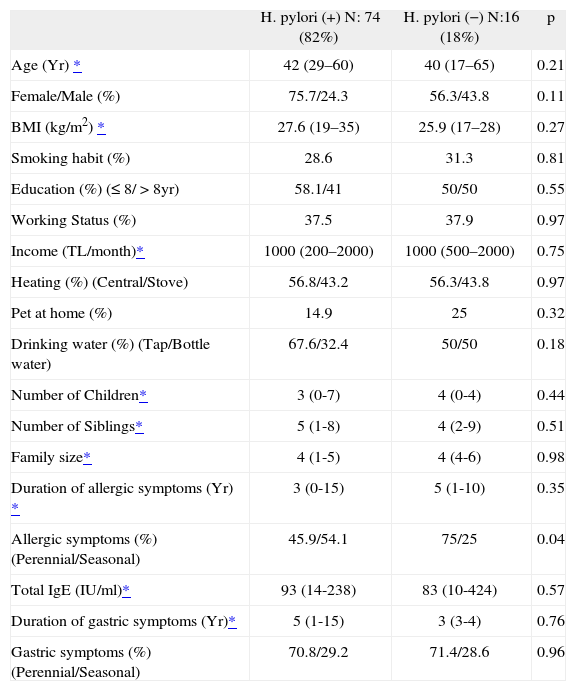

The possible risk factors for the development of H. pylori infection were compared (Table II). The demographic and socioeconomic parameters, smoking status and educational level were similar within the groups. Most of the subjects were ex-smokers or non-smokers. Pet ownership was low among all groups with a range of 15–25 %. Almost two thirds of H. pylori (+) subjects were found to drink tap water. The number of children and siblings were similar between the groups as well as the family size. Although the duration of allergic symptoms was not different between the H. pylori (+) and (−) groups, perennial allergy was significantly higher in H. pylori (−). Perennial symptoms were related with a decreased risk of H. pylori infection (OR 1.6; 95 % CI 1.1 to 2.3), whereas seasonal allergic symptoms were related with an increased risk for H. pylori infection (OR 0.4; 95% CI 0.2 to 1.1) (p = 0.04).

Comparison of possible risk factors for H. pylori infection

| H. pylori (+) N: 74 (82%) | H. pylori (−) N:16 (18%) | p | |

| Age (Yr) * | 42 (29–60) | 40 (17–65) | 0.21 |

| Female/Male (%) | 75.7/24.3 | 56.3/43.8 | 0.11 |

| BMI (kg/m2) * | 27.6 (19–35) | 25.9 (17–28) | 0.27 |

| Smoking habit (%) | 28.6 | 31.3 | 0.81 |

| Education (%) (≤ 8/ > 8yr) | 58.1/41 | 50/50 | 0.55 |

| Working Status (%) | 37.5 | 37.9 | 0.97 |

| Income (TL/month)* | 1000 (200–2000) | 1000 (500–2000) | 0.75 |

| Heating (%) (Central/Stove) | 56.8/43.2 | 56.3/43.8 | 0.97 |

| Pet at home (%) | 14.9 | 25 | 0.32 |

| Drinking water (%) (Tap/Bottle water) | 67.6/32.4 | 50/50 | 0.18 |

| Number of Children* | 3 (0-7) | 4 (0-4) | 0.44 |

| Number of Siblings* | 5 (1-8) | 4 (2-9) | 0.51 |

| Family size* | 4 (1-5) | 4 (4-6) | 0.98 |

| Duration of allergic symptoms (Yr) * | 3 (0-15) | 5 (1-10) | 0.35 |

| Allergic symptoms (%) (Perennial/Seasonal) | 45.9/54.1 | 75/25 | 0.04 |

| Total IgE (IU/ml)* | 93 (14-238) | 83 (10-424) | 0.57 |

| Duration of gastric symptoms (Yr)* | 5 (1-15) | 3 (3-4) | 0.76 |

| Gastric symptoms (%) (Perennial/Seasonal) | 70.8/29.2 | 71.4/28.6 | 0.96 |

TL: Turkish Lira; Yr: year

The prevalence of H. pylori strongly varies between the developing and developed countries as does the prevalence of atopy. In earlier studies, it was shown that 70 % of adults have antibodies against H. pylori and more than 30% of subjects acquire infection before teenage in the Turkish population.17 Despite recent reports suggesting a decreasing trend in H. pylori infection,18,19 the relatively high H. pylori prevalence (83 %) found in this study suggests that the infection is still prevalent among our group of patients.

Some epidemiologic studies showed that in subjects with H. pylori seropositivity, the prevalence of atopic diseases –asthma, rhinitis and eczema– was lower than in H. pylori-negative subjects, thus supporting the 'hygiene hypothesis.3,6,8 However, neither the atopic status between the H. pylori (+) and H. pylori (−) groups, nor the H. pylori positivity between the atopic and non-atopic groups differed in this study. Patients with allergic symptoms were not excluded in the recruitment stage. We found a higher prevalence of asthma in the H. pylori (−) group which was insignificant after the adjustment for ORs. This is consistent with the previous studies using anti-H. pylori IgG and anti-H. pylori-CagA IgG levels in which the prevalence of H. pylori infection was similar between the asthmatic and the control groups.20,21 In accordance with our findings, Uter et al. showed that there was no consistent pattern indicative of increased or decreased risk of atopic diseases concerning H. Pylori among university students. Furthermore, results from a community-based sample of young adults showed no evidence that H. pylori infection was associated with lower levels of IgE sensitization.16 Inconsistent findings from different populations may result as a reflection of regional variations in the epidemiology of this infection, as well as different living conditions.

An interesting part of this study was to determine the association between H. pylori infection and atopic diseases other than respiratory allergy. This is one of the few studies –at least to our knowledge– that evaluates the association between H. pylori and all atopic diseases regarding allergic inflammation. An association between H. pylori antibodies and food allergy presenting as atopic dermatitis has been reported.10–12 Long-term exposure to food allergens increases the intensity of inflammation of the gastric mucosa infected with H. pylori in atopic patients. The hypothesis that the easy transition of food allergens ends in allergic inflammation has not been confirmed in all studies.15 Recently, infection of the urinary tract was found to be the most frequently documented cause, followed by Chlamydia pneumonia and H. pylori in patients with acute urticaria.22 Although, these reports support the idea that H. pylori could be one of the factors in allergic inflammation, no such correlation was observed between H. pylori infection and food allergy and/or urticaria in our study population.

In this study, we also aimed to determine the prevalence of atopy among H. pylori (+)s and H. pylori (−)s, in order to assess the possible interaction between these two disease states. However, our data suggest that allergic inflammation was not inversely related to H. pylori, nor vice versa. As the transmission mainly occurs during childhood, in developing countries like Turkey, the infection that is more prevalent in older ages can be explained by the lower socioeconomic conditions during childhood. Therefore, the major difference in the prevalence rate of infection in developing and developed countries simply implies the contrast in hygienic conditions during childhood which may reflect its results to adult term. Thus the factors responsible for the development of atopy might be inversely related to the infection. Low outcome, high household density of children, and use of stove for heating, transmission via food such as uncooked vegetables and municipal water, transmission from person to person by interfamily clustering and from mother to child, were reported to be important risk factors for H. pylori infection.9,23,24 Among many different environmental risk factors questioned, we could not attribute a casual role of H. pylori infection on atopy in this adulthood population. In our study, histological diagnosis of H. pylori that shows an active infection, rather than serologic diagnosis, was used. Some factors like drinking tap water may be important as the reflection of relatively poor hygienic conditions. In this study, it is hard to predict the preventive role of pets on atopic sensitisation, because of the low ownership rate in Turkey. Brenner et al. proposed that drinking alcohol has a protective and coffee a predictive, effect against H. pylori infection.25 As three quarters of our study population consisted of females, relatively low alcohol consumption in this gender may be assumed as being responsible for the relatively higher prevalence of H. pylori infection.

Another important finding was the seasonal allergic symptoms that were related with an increased risk of H. pylori infection. This coincidence is hard to explain. Hypersensitivity in the gastrointestinal system may occur simultaneously with the development of inflammation in the upper and lower airways.26 It is known that gastric symptoms of H. pylori infection frequently occur during winter and spring, and hypersensitivity to pollens which show seasonal symptoms might result in exacerbation of gastric symptoms due to accumulation of eosinophils in the gastric mucosa and may facilitate H. pylori infection.27

In conclusion, the results of our study did not support the hypothesis that H. pylori infection was associated with a substantially reduced risk of atopic disorders. Although the sample size is relatively small for a definitive conclusion, the high prevalence of H. pylori might be partly related to low socioeconomic status and traditional living conditions in Turkey. Further investigations with larger populations are needed in order to determine the extent to which allergic inflammation and the specific infections are associated.