Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic inflammatory emerging disease of the oesophagus with immunoallergic aetiology. The allergens involved have not been clearly defined and may depend on the exposure of the population to aeroallergens or food antigens.

Materials and methodsPatients diagnosed with EoE between 2006 and 2011 were referred to our Allergy Section. Patch and skin prick tests (SPT) with aeroallergens and foods were performed, and total and specific IgE levels, eosinophil cationic protein levels and eosinophil count were determined.

Results43 patients were included. 36 (83.7%) were atopic. 29 patients presented choking, 19 dysphagia, 9 food impaction with urgent endoscopy, 4 chest pain, 1 isolated vomiting and 1 epigastric pain. 22 had two or more symptoms. The mean duration of symptoms was 3.73 years. Concomitant allergic diseases included rhinoconjunctivitis and/or asthma (31 patients), IgE food allergy (21 patients) and atopic dermatitis (3 patients).

32 (74%) were sensitized to aeroallergens, of which 90% were sensitized to pollens; 23 (54%) showed positive tests to foods and 12 of them (52%) to lipid transfer proteins (LTP).

Of the 29 pollen-allergic patients, 15 (52%) were sensitized to plant foods and 10 (34.4%) to LTP.

ConclusionsOur findings support those reported in the literature: the disease is more common in men aged 30–40 years with at least a three-year history of symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, sensitized to pollens, the predominant aeroallergen in our area, but also to plant foods or panallergens. These results increase the evidence for an immunoallergic aetiology and can help us in the early diagnosis of EoE.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) was first described by Attwood in 19931 in 12 adult patients presenting with dysphagia. It is an emerging chronic inflammatory disease2 of the oesophagus that affects children and adults. EoE is probably triggered by a hypersensitivity mechanism to foods and/or aeroallergens2 and is characterized by a T helper type 2-mediated inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract,2–16 similar to the inflammation produced by aeroallergens in the respiratory tract.3 Sensitization to foods and/or aeroallergens probably plays an important role in the aetiology of EoE.4 This assumption is based on an inter-relationship between the respiratory and digestive tracts as a consequence of the systemic response that characterizes allergic diseases.5

The prevalence of EoE has been increasing over the past decade, both in children and in adults.4,6,7,17,18 It is not known whether this is due to a true increase in prevalence or to an improved understanding of the disease and a multidisciplinary approach that is leading to a higher rate of diagnosis.

It is manifested by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and histologically occurs as a predominantly eosinophilic inflammation.17 A significant esophageal eosinophilia has been shown in 1% of the general population, but only 4% of the adult population had marked infiltration consistent with definite EoE19 being more common in developed countries and in men. The form of presentation and the intensity, frequency and duration of symptoms vary considerably.6 However, the sociodemographic characteristics are less variable, as all authors report that the immunoallergic aetiology parallels that of atopy.6,18 Onset occurs during childhood in 65% of cases, although it has been described in all age groups.18

Its physiopathology is based on a combination of factors:

- (a)

An immunoallergic mechanism mediated by sensitized T-lymphocytes through a TH2-type immunologic reaction to certain elements in the diet or in the environment that act as food allergens or aeroallergens,2,4,17,18 or by a mixed mechanism, also mediated by IgE immunoglobulin (Ig E).

- (b)

The presence of gastro-esophageal reflux that induces an abnormal immune response and could lead to the onset of EoE, or EoE being itself a factor that predisposes to gastro-esophageal reflux.18

The province of Ciudad Real is located in central Spain. The more prevalent airborne pollens are Poaceae, Olea and Chenopodiacear-Amaranthaceae.20 Our population has a high level of sensitization to these pollens and to plant foods, both of which are rich in panallergens (lipid transfer proteins [LTP] and/or profilins) with marked cross-reactivity.6,8 The relationship between hay fever and plant-food allergy in the Mediterranean region could mean that respiratory sensitization to panallergens present in pollens constitutes a risk factor for being sensitized to multiple foods and plays a role in the subsequent appearance of EoE, particularly in adults.9 Therefore, the identification of the allergic sensitization of the patients in our series would be of major importance to establish the possible relationship between EoE and the allergens that could be the triggers of the disease.

We performed this study to determine the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with EoE in our reference area of Ciudad Real city and province. We also evaluated the frequency of allergic sensitization to foods, aeroallergens and panallergens in patients diagnosed with EoE, and studied relevant laboratory parameters: total IgE (IgEt), serum eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) and peripheral blood eosinophil count.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis was a prospective cross-sectional descriptive study.

Study populationThe study population included patients diagnosed with EoE between 2006 and 2011 in the Gastroenterology Department of Ciudad Real University General Hospital (Eosinophilic Esophagitis Research Group) and subsequently referred to the Allergy Department of the Hospital. The diagnosis was based on compatible clinical manifestations (symptoms of esophageal dysfunction) and the results of the esophageal biopsy; based on the criteria published in the latest consensus of the American Clinical Committee and on the criteria of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) and the World Allergy Organization (WAO).17

This study was approved by the Hospital's Ethics and Clinical Research Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Clinical evaluationThe following data were recorded for each patient: age, sex, gastrointestinal manifestations, duration of the disease, foods that triggered symptoms, history of rhinoconjunctivitis (duration and seasonal characteristics), asthma, atopic dermatitis or hay fever, food-related immediate symptoms prior to the onset of EoE, need for urgent endoscopic treatment and result of the biopsy on which the diagnosis was based.

An allergological study was then performed using a standard series of tests10,11,21 on all patients in order to achieve homogeneity and avoid bias. Prick tests were performed with a commercial series of aeroallergens (Dactylis glomerata, Lolium perenne, Olea europaea, Cupressus Arizonica, Platanus acerifolia, Artemisia vulgaris, Chenopodium alba, Plantago lanceolata, Salsola kali, Cladosporium, Alternaria, Aspergillus, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, Lepidoglyphus destructor, cat and dog dander); foods (peanut, corn, wheat, soy, egg white, cod, tuna, prawns, cow's milk, lentils, grass-pea flour, mustard and peach)21; and panallergens (LTP and profilins) plus latex and Anisakis. These tests were carried out following the recommendations of the EAACI and prick–prick tests were performed when fresh foods were implicated.

The allergens used were supplied by ALK-Abelló Laboratories (Madrid, Spain).

Histamine (10mg/ml) and normal saline were used as the positive and negative controls. A wheal with an area 7mm2 larger or a diameter 3mm larger than the negative control (saline solution) was considered positive.

The peripheral blood eosinophil count and IgE levels were determined, together with the specific IgE levels (cellulose-absorbed phase analytical method, Phadia, Upsala, Sweden) for the series of foods (cereals, legumes, milk, egg, fish, crustaceans, mustard, dried fruits, peach) plus latex, Anisakis, aeroallergens and patient-reported foods10; concentrations of specific IgE >0.35kU/L and of serum ECP >11.5μg/ml were considered to be positive results.

Patch tests were then performed with the foods included in the above series plus latex, Anisakis, aeroallergens and panallergens (LTP and profilins) and the foods reported by the patient in each case11,21. Reagents for patch test were the same commercial extract used for skin prick test (SPT), but they were prepared at a concentration of 5% in water and in petrolatum, with readings at 48 and 96h. Patch tests were also conducted with the implicated foods, raw or cooked, depending on their usual form of preparation for consumption.

Statistical analysisThe absolute frequencies were calculated for the qualitative variables, and the mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum values for the quantitative variables, with their 95% confidence intervals.

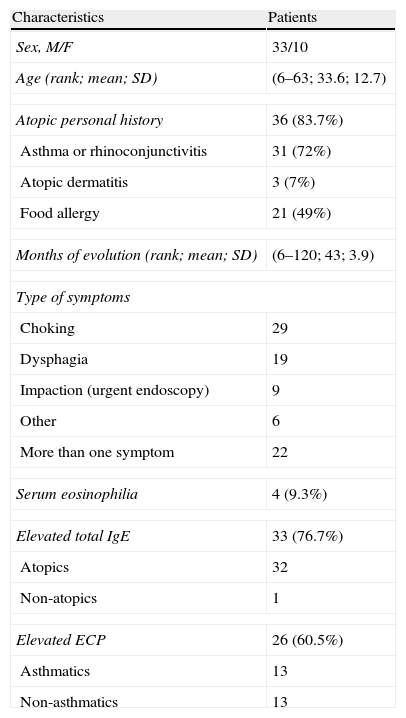

ResultsA total of 43 patients (33 men and 10 women; mean age, 33.6 years; age range, 6–63 years) were diagnosed with EoE between 2006 and 2011 in the Gastroenterology Department (Eosinophilic Esophagitis Research Group) of our hospital and referred to our allergy department. Their basal demographic, clinical and laboratory data are summarized in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients.

| Characteristics | Patients |

| Sex, M/F | 33/10 |

| Age (rank; mean; SD) | (6–63; 33.6; 12.7) |

| Atopic personal history | 36 (83.7%) |

| Asthma or rhinoconjunctivitis | 31 (72%) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 3 (7%) |

| Food allergy | 21 (49%) |

| Months of evolution (rank; mean; SD) | (6–120; 43; 3.9) |

| Type of symptoms | |

| Choking | 29 |

| Dysphagia | 19 |

| Impaction (urgent endoscopy) | 9 |

| Other | 6 |

| More than one symptom | 22 |

| Serum eosinophilia | 4 (9.3%) |

| Elevated total IgE | 33 (76.7%) |

| Atopics | 32 |

| Non-atopics | 1 |

| Elevated ECP | 26 (60.5%) |

| Asthmatics | 13 |

| Non-asthmatics | 13 |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male.

The presenting symptoms of the disease included choking (defined as a transient esophageal retention with spontaneous resolution) (29 patients); food impaction that needed urgent endoscopy (9 patients); dysphagia (19 patients); chest pain (4 patients); isolated vomiting (1 patient) and epigastric pain (1 patient). Twenty-two patients (51%) had more than one presenting symptom. Urgent endoscopy was required by nine patients (20.9%). The mean course of the disease before medical consultation was 3.73 years (rank 6 months to 22 years).

Thirty-six patients (83.7%) were atopic. Only three patients (7%) had a history of atopic dermatitis. A history of allergic respiratory diseases (rhinitis, rhinoconjunctivitis and/or asthma) was detected in 31 patients (72%): rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma in 25 patients (80.6%); only asthma in two patients (6.4%), only rhinitis in 1 patient (3.2%) and only rhinoconjunctivitis in three patients (9.6%).

Twenty-one patients (49%) were allergic to foods, with a history of an immediate reaction and a positive skin test and/or specific IgE to the implicated food prior to the diagnosis of EoE.

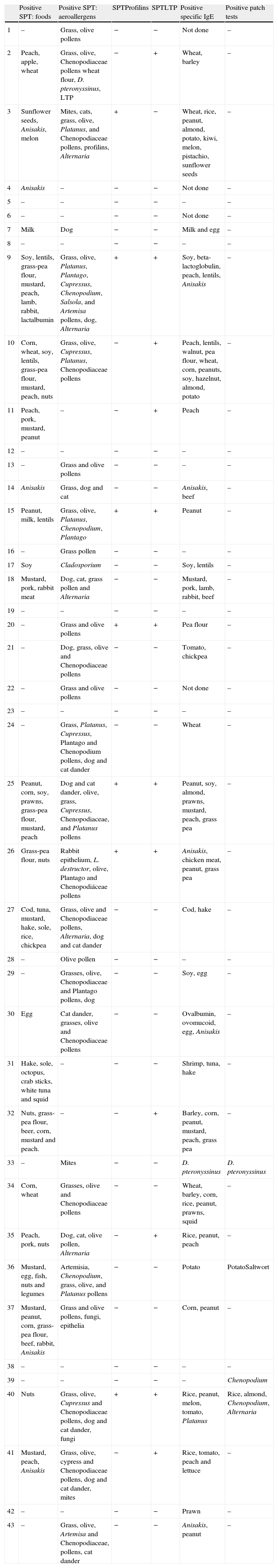

The results of the allergy tests are shown in Table 2. Positive SPT to aeroallergens were detected in 32 patients (74.41%): 29 (90.62%) were sensitized to pollens, most of them to grass (82.7%) or olive pollens (79.3%); monosensitization was detected to mites, fungi and epithelia in one patient each (3.13%). Eleven patients (25.6%) were not sensitized to aeroallergens.

Results of the allergological study of the 43 patients.

| Positive SPT: foods | Positive SPT: aeroallergens | SPTProfilins | SPTLTP | Positive specific IgE | Positive patch tests | |

| 1 | – | Grass, olive pollens | − | − | Not done | – |

| 2 | Peach, apple, wheat | Grass, olive, Chenopodiaceae pollens wheat flour, D. pteronyssinus, LTP | − | + | Wheat, barley | – |

| 3 | Sunflower seeds, Anisakis, melon | Mites, cats, grass, olive, Platanus, and Chenopodiaceae pollens, profilins, Alternaria | + | − | Wheat, rice, peanut, almond, potato, kiwi, melon, pistachio, sunflower seeds | – |

| 4 | Anisakis | – | − | − | Not done | – |

| 5 | – | – | − | − | – | – |

| 6 | – | – | − | − | Not done | – |

| 7 | Milk | Dog | − | − | Milk and egg | – |

| 8 | – | – | − | − | – | – |

| 9 | Soy, lentils, grass-pea flour, mustard, peach, lamb, rabbit, lactalbumin | Grass, olive, Platanus, Plantago, Cupressus, Chenopodium, Salsola, and Artemisa pollens, dog, Alternaria | + | + | Soy, beta-lactoglobulin, peach, lentils, Anisakis | – |

| 10 | Corn, wheat, soy, lentils, grass-pea flour, mustard, peach, nuts | Grass, olive, Cupressus, Platanus, Chenopodiaceae pollens | − | + | Peach, lentils, walnut, pea flour, wheat, corn, peanuts, soy, hazelnut, almond, potato | – |

| 11 | Peach, pork, mustard, peanut | – | − | + | Peach | – |

| 12 | – | – | − | − | – | – |

| 13 | – | Grass and olive pollens | − | − | – | – |

| 14 | Anisakis | Grass, dog and cat | − | − | Anisakis, beef | – |

| 15 | Peanut, milk, lentils | Grass, olive, Platanus, Chenopodium, Plantago | + | + | Peanut | – |

| 16 | – | Grass pollen | − | − | – | – |

| 17 | Soy | Cladosporium | − | − | Soy, lentils | – |

| 18 | Mustard, pork, rabbit meat | Dog, cat, grass pollen and Alternaria | − | − | Mustard, pork, lamb, rabbit, beef | – |

| 19 | – | – | − | − | – | – |

| 20 | – | Grass and olive pollens | + | + | Pea flour | – |

| 21 | – | Dog, grass, olive and Chenopodiaceae pollens | − | − | Tomato, chickpea | – |

| 22 | – | Grass and olive pollens | − | − | Not done | – |

| 23 | – | – | − | − | – | – |

| 24 | – | Grass, Platanus, Cupressus, Plantago and Chenopodium pollens, dog and cat dander | − | − | Wheat | – |

| 25 | Peanut, corn, soy, prawns, grass-pea flour, mustard, peach | Dog and cat dander, olive, grass, Cupressus, Chenopodiaceae, and Platanus pollens | + | + | Peanut, soy, almond, prawns, mustard, peach, grass pea | – |

| 26 | Grass-pea flour, nuts | Rabbit epithelium, L. destructor, olive, Plantago and Chenopodiáceae pollens | + | + | Anisakis, chicken meat, peanut, grass pea | – |

| 27 | Cod, tuna, mustard, hake, sole, rice, chickpea | Grass, olive and Chenopodiaceae pollens, Alternaria, dog and cat dander | − | − | Cod, hake | – |

| 28 | – | Olive pollen | − | − | – | – |

| 29 | – | Grasses, olive, Chenopodiaceae and Plantago pollens, dog | − | − | Soy, egg | – |

| 30 | Egg | Cat dander, grasses, olive and Chenopodiaceae pollens | − | − | Ovalbumin, ovomucoid, egg, Anisakis | – |

| 31 | Hake, sole, octopus, crab sticks, white tuna and squid | – | − | − | Shrimp, tuna, hake | – |

| 32 | Nuts, grass-pea flour, beer, corn, mustard and peach. | – | − | + | Barley, corn, peanut, mustard, peach, grass pea | – |

| 33 | – | Mites | − | − | D. pteronyssinus | D. pteronyssinus |

| 34 | Corn, wheat | Grasses, olive and Chenopodiaceae pollens | − | − | Wheat, barley, corn, rice, peanut, prawns, squid | – |

| 35 | Peach, pork, nuts | Dog, cat, olive pollen, Alternaria | − | + | Rice, peanut, peach | – |

| 36 | Mustard, egg, fish, nuts and legumes | Artemisia, Chenopodium, grass, olive, and Platanus pollens | − | − | Potato | PotatoSaltwort |

| 37 | Mustard, peanut, corn, grass-pea flour, beef, rabbit, Anisakis | Grass and olive pollens, fungi, epithelia | − | − | Corn, peanut | – |

| 38 | – | – | − | − | – | – |

| 39 | – | – | − | − | – | Chenopodium |

| 40 | Nuts | Grass, olive, Cupressus and Chenopodiaceae pollens, dog and cat dander, fungi | + | + | Rice, peanut, melon, tomato, Platanus | Rice, almond, Chenopodium, Alternaria |

| 41 | Mustard, peach, Anisakis | Grass, olive, cypress and Chenopodiaceae pollens, dog and cat dander, mites | − | + | Rice, tomato, peach and lettuce | – |

| 42 | – | – | − | − | Prawn | – |

| 43 | – | Grass, olive, Artemisa and Chenopodiaceae, pollens, cat dander | − | − | Anisakis, peanut | – |

Abbreviations: D, dermatophagoides; L, lepidoglyphus; LTP, lipid transfer protein; SPT, skin prick tests.

Twenty-three patients (53.5%) showed positive skin tests to food extracts; 18 (78.2%) were sensitized to at least one plant food. Fifteen of them were also SPT positive to pollens (83.3%).

Sensitization to panallergens (LTP and/or profilins) was detected in 13 patients (30.23%): 12 (27.90%) to LTP, and seven (16.27%) to profilins.

Fifteen (51.7%) of the patients sensitized to pollens showed positive SPT to at least one plant food. Ten (66.6%) of these patients, sensitized both to pollens and foods, were also sensitized to panallergens (profilin or LTP).

Patch tests were positive in four patients (9.3%). One patient was positive to rice, almond, Chenopodium and Alternaria, one to potato and Salsola pollen, one to Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, and another to Chenopodium. The patch tests in these four patients were positive at both 48 and 96h in petrolatum. These four patients also had positive SPT to these allergens.

Peripheral eosinophilia was detected in four patients (9.3%), all of whom were atopic. Total IgE levels were elevated in 88.5% of atopic patients, and only in 14.5% of non-atopics. Sixty percent of the patients had elevated serum ECP levels and half of these patients were asthmatic. Three of the only four non-asthmatic and non-atopic patients had elevated serum ECP.

In our series two patients (5%) developed subsequently eosinophilic esophago-gastroenteritis. One of these patients has recently been diagnosed with Churg–Strauss syndrome.

DiscussionThe results of this study agree with previous reports in the demographic and clinical data of patients with EoE, which affect mostly middle-aged atopic males and manifest with dysphagia and choking. Aeroallergens to which atopic patients are sensitized relate to the aerobiology of the region, with pollens being the most frequent allergens. It is remarkable the high frequency of allergy sensitization to vegetable foods in our study, probably due to sensitization to plant panallergens through the respiratory tract in pollinosis, which is the predominant respiratory allergy in our area.

As reported in the literature, we also found a higher frequency of the disease in atopic men between 30 and 40 years of age2,3,6,12,13,17,18,21,22 and the large proportion of atopic patients in our series (83.7%) supports the widely held view that EoE is an atopy-related disease.2–18,21,22

The elevation of ECP levels in atopic patients may indicate not only esophageal but also bronchial inflammation. For this reason, ECP levels could only be useful in non-asthmatic patients with EoE. Only four non-atopic non-asthmatic patients were included in the study but three of them showed elevated ECP. These data, although scarce, may indicate the usefulness of the determination of ECP in these patients.

Measurements of the total IgE levels and eosinophil count provide little useful information in this disease. The only definitive test for diagnosing EoE is the three sample biopsy of the oesophagus. Furthermore, for a correct diagnosis, it is important to take samples not only from the oesophagus but also from the stomach and duodenum as, in our series, two patients (4.7%) had eosinophilic esophago-gastroenteritis that, in one patient, later progressed to Churg–Strauss syndrome.

The pathogenesis of EoE is considered to be due to a mixed humoral and cellular mechanism. Positive patch testing would reflect the role of T lymphocytes in esophageal inflammation. However, in our series we only obtained positive results in four patients in whom patch and prick tests were positive. Therefore patch tests did not yield useful results in our patients, although the fact that they were not standardized could have affected the results.

Food sensitization constitutes the principal aetiological hypothesis since EoE was first described; Lucendo et al.23 recently published a study performed in our geographical region that confirmed the implication of foods in the pathogenesis of the disease. They consider food antigens to be the major triggers in inducing and maintaining eosinophilic esophageal inflammation and, after an empiric 6-food elimination diet they found a remission of the disease in 73.1% of the patients, with milk being the most common offending food antigen, followed by wheat, eggs and legumes but, if we consider food groups, cereals were the most frequently implicated foods. They found very low concordance between allergy tests and food reintroduction challenges. Nuts, legumes and wheat were, however, the foods that exhibited more positive SPT and, again, plant foods showed higher IgE levels in both diet responder and non-responder patients. Our results were similar to this report in that plant foods were those that offered more positive results in the immediate allergy tests but we did not perform elimination diets or other interventions to assess the clinical implications of these food allergens

Besides foods, sensitization to aeroallergens is gradually appearing more relevant. In our area, pollens as the predominant aeroallergens could produce inflammatory lesions in the oesophagus similar to those produced in the airways,24 directly, or through cross-reactivity with plant foods with common allergens that, in contact with the digestive tract, could induce the same lesions.25 The high prevalence of sensitization to these foods and to panallergens in our series corroborates the relationship between pollen and food allergy described in the literature.26–30 Some reports principally relate EoE with the ingestion of plant foods due to a secondary mechanism of sensitization.3,5,6,12,14–16 The results of our study agree with previous ones in that the prevalence of food sensitization in patients with EoE is in accordance with the aerobiology of the region.5,9,15 Furthermore, authors of recent studies in the Mediterranean area have stated that food sensitization among patients with EoE is most common to legumes and that 93% of those patients were polysensitized to pollens.9,31

All these data may support the involvement of respiratory sensitization in the aetiology of EoE and would contribute to consider EoE as a consequence of the interrelationship between the respiratory and digestive tracts,24 not only from the histopathological and cellular point of view,25 but also from an immunochemical approach, due to the cytokines that mediate in the condition.24

One of the reports from Lucendo et al. also contributes to this idea as they have observed that the damage caused to the esophageal mucosa is similar to that observed in the respiratory mucosa in asthma.25

Therefore, measures to avoid airborne allergens and dietary allergens should be considered as they are in other allergic diseases.

The major limitation of our study is that it is a descriptive one so we can only obtain data on the clinical and allergological characteristics of the patients but no therapeutic consequences, as we did not determine the clinical implications of the observed sensitizations. We believe, however, that this study may provide allergologists with valuable information for the early diagnosis of the condition.

When treating atopic patients under 40 years of age with a history of food or respiratory allergy, or sensitized to panallergens, it is very important to investigate the history data that can guide us to the diagnosis of this process by asking about symptoms in relation to food intake, dietary habits, etc.

In conclusion, there is a high prevalence of sensitization to pollens and plant foods in patients with EoE in our area. This disease is frequently associated with rhinoconjunctivitis and/or asthma.

Serum eosinophils and total IgE are not useful in the diagnosis of the disease but ECP may give some help in non-asthmatic and non-atopic patients. The use of patch test for the diagnosis of foods sensitizations in patients with EoE has poor outcomes, although further studies are required after standardization of the test with food allergens.

The high prevalence of sensitization detected to pollens and panallergens in patients with EoE in our area seems to be related to the aerobiology of our region. Further studies are needed to confirm the role of theses allergens in the pathophysiology of the disease.

Allergologists should take into account the demographic, clinical and allergological profile of patients with eosinophilic esophagitis in their health area, thus the disease would be suspected sooner and the diagnosis made at an earlier stage.

Ethical disclosuresThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

We would like to thank the Gastroenterology and Pathology Departments of the Ciudad Real University General Hospital for their collaboration.

The study was completely supported by the Ciudad Real University General Hospital (SESCAM, Health Service of Castilla-La Mancha, Spain).