Determining whether patients with cow's milk allergy (CMA) can tolerate foods produced with baked milk could provide a better quality of life, a better prognosis, and an option for desensitization.

ObjectivesThe aim of this study was to identify which patients over four years of age with persistent CMA could tolerate baked milk, to compare the clinical and laboratory characteristics of reactive and non-reactive groups and to describe their clinical evolution.

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted (January/13 to November/14) that included all the patients followed at a food allergy center who met the inclusion criteria. The patients underwent an oral food challenge (OFC) with a muffin (2.8g of cow's milk protein). To exclude cow's milk (CM) tolerance, the patients were subsequently challenged with unheated CM.

ResultsThirty patients met all the inclusion criteria. Fourteen patients (46.7%) were considered non-reactive to baked milk and reactive to unheated CM. When the groups that were reactive and non-reactive to baked milk were compared, no statistically significant differences in clinical features were found. The prick test for α-lactalbumin (p=0.01) and casein (p=0.004) and the serum specific IgE for casein (p=0.05) presented statistical differences. After one year, none of the patients who were reactive to baked milk were ingesting CM, while 28% of the tolerant patients were consuming fresh CM (p=0.037).

ConclusionsBaked milk can be tolerated by patients with CMA, especially those with lower levels of casein and α-lactalbumin. This option can improve quality of life and accelerate tolerance.

Cow's milk allergy (CMA) is the most common childhood food allergy, with a prevalence of 2–3% in children.1,2 This disorder presents a risk of severe reaction and even potentially fatal outcomes. The natural history of CMA has been described as presenting a good prognosis, with most children becoming tolerant to cow's milk (CM) spontaneously at an early age: 80% are tolerant at three years of age.3 However, in recent years, less optimistic results have been found, showing only a 19% tolerance at four years of age.4

The traditional treatment for CMA is restricting the intake of CM and its products, although doing so leaves these patients unprotected when they come into contact with small amounts of the antigen.5–8 Currently, there is evidence that the ingestion of small amounts of milk could induce desensitization or tolerance.9–12

Recent studies have described that an oral food challenge (OFC) using baked milk can define two phenotypes of patients with CMA: those who are reactive to baked milk products and those who are non-reactive. These studies reported a 65–83% tolerance of heated milk,13–16 which indicates a better prognosis in terms of earlier tolerance of CM and a better quality of life. Subsequent studies have suggested that baked milk could be an option for desensitization which is easy to perform and has a low number of adverse effects.17–20 When exposed to high temperatures, CM antigens can lose their allergenic potential (in the case of conformational epitopes, such as β-lactoglobulin) or retain it (in the case of linear epitopes, especially casein).21–24

To identify whether a patient with CMA can tolerate a product containing baked milk, an OFC with baked milk is recommended because to date, clinical and laboratory data have been poorly able to make the distinction between baked milk tolerance and non-tolerance. The main objectives of this study were to identify patients over four years of age with persistent CMA who could tolerate the ingestion of baked milk, to compare the clinical and laboratory characteristics of those who are reactive to baked milk and those who are non-reactive, and to describe the clinical evolution after one year of consuming baked milk products.

This paper reports the Brazilian statistics regarding baked milk tolerance, a topic on which there are no published data for Latin America. It followed a careful methodological design that included a blinded researcher, collected data simultaneously with the OFC, and chose inclusion criteria that ensured a homogeneous sample. It utilizes an easily made baked milk recipe with a high CM protein concentration, thus facilitating patient compliance. The ability to identify a patient as baked-milk tolerant can lead to a significant improvement in quality of life, a better prognosis, and the possibility of desensitization. Finally, finding a clinical or laboratory marker for baked milk tolerance would make it possible to evaluate which patients can undergo an OFC with less risk.

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted between January/13 and November/14. The sample was selected from patients who attended a tertiary food allergy center (Allergy & Immunology Unit, Department of Pediatrics, Instituto da Criança – HCFMUSP – São Paulo), met the inclusion criteria and agreed to carry out the OFC. The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee from the Hospital das Clínicas, School of Medicine, Universidade de São Paulo.

The eligibility criteria included individuals between 4 and 18 years of age who had a diagnosis of IgE-mediated CMA based on1: a clinical history consistent with IgE-mediated manifestations up to two hours after exposure to CM2; a positive specific IgE to CM and/or fractions (serum IgE≥0.35kUA/L or prick test ≥3mm); and3 a clinical response to double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges (DBPCFC) for milk upon diagnosis of CMA, except those with a history of anaphylaxis. All patients or guardians signed an informed consent form after they were notified about the study, including the possibility of severe reactions.

The exclusion criteria included pregnancy, acute infectious disease, chronic disease treated with immunosuppressive drugs, uncontrolled asthma, atopic dermatitis, eosinophilic oesophagitis, any allergic reaction in the past year to baked milk products, allergy to other ingredients used in the preparation, and a negative OFC with unheated cow's milk. All of the patients had a history of ingestion of soybeans, wheat and egg without any reaction.

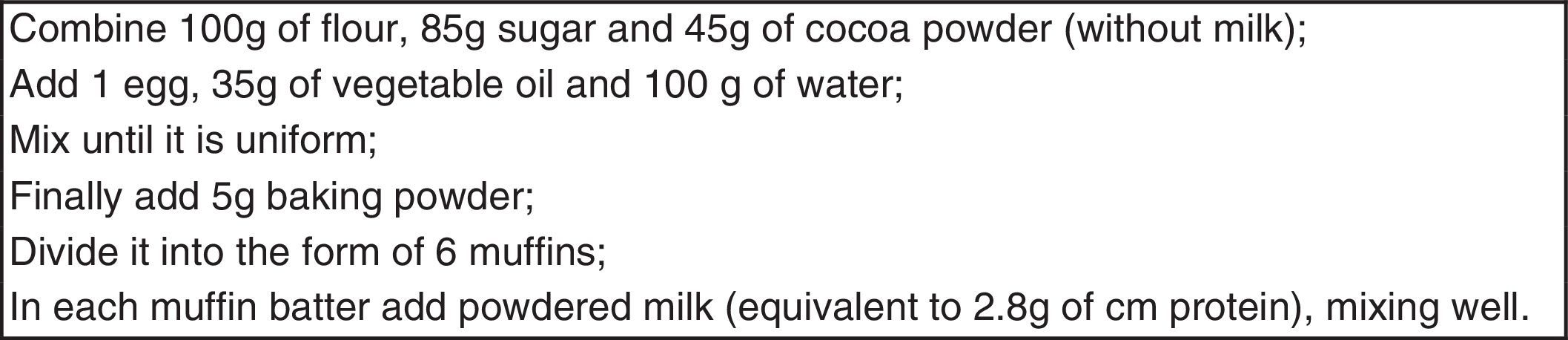

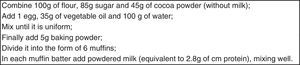

The baked milk product was prepared by the Nutrition Division a day before each test. Each muffin contained 2.8g of CM protein (corresponding to 100mL) and was submitted to oven heating at 350°F for 30min according to references in the literature13 adapted for Brazilian cooking (Fig. 1).

The selected patients were admitted to a hospital and provided venous access and monitoring under medical supervision. Each patient received a quarter of the muffin every 15min, with clinical assessment (patient complaints, physical examination, monitoring vital signs, oxygen saturation, blood pressure and peak flow) prior to each dose; observation was maintained for two hours after the challenge. The challenge was discontinued at the first sign of an objective reaction, and the patient was properly assisted and medicated whenever necessary. The patients were defined as non-reactive to baked CM if they did not present any allergic reaction after ingesting an entire muffin. Patients who had no history of reaction to fresh CM in the past year were submitted to a challenge with unheated CM (300mL, corresponding to 10g of protein) to assess whether they would be considered reactive to CM.25,26 The researcher who conducted the OFC did not have access to the patients’ recent laboratory data at the time of testing.

The following clinical features were obtained before the test: gender, history of previous anaphylaxis, reports for the milk trace intake, reports of allergic reactions to CM in the past year, history of anaphylaxis in the past year, rhinitis, asthma, history of other allergies, and the family history of rhinitis, asthma and other allergies. The following laboratory tests were conducted simultaneous to the OFC: eosinophil blood count, total IgE, and serum specific IgE (ImmunoCAP®) to CM, α-lactalbumin, β-lactoglobulin and casein. Prick tests were also performed for CM, α-lactalbumin, β-lactoglobulin and casein according to the modified Pepys technique. The positive criterion was wheal larger than 3mm compared with the negative control. For the comparative analysis, we used the mean of the two perpendicular diameters.27

The patients who were reactive to baked milk were instructed to maintain the restrictive diet, while those who tolerated baked milk were advised to continue the daily intake of one homemade muffin containing 1.4g of CM protein in addition to foods containing traces of milk.

For the data analysis, the R program version 3.2.2 was used. A p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Nominal variables were compared using the Fisher exact test or Chi-square test. Numerical variables were compared using the t test or Mann–Whitney test.

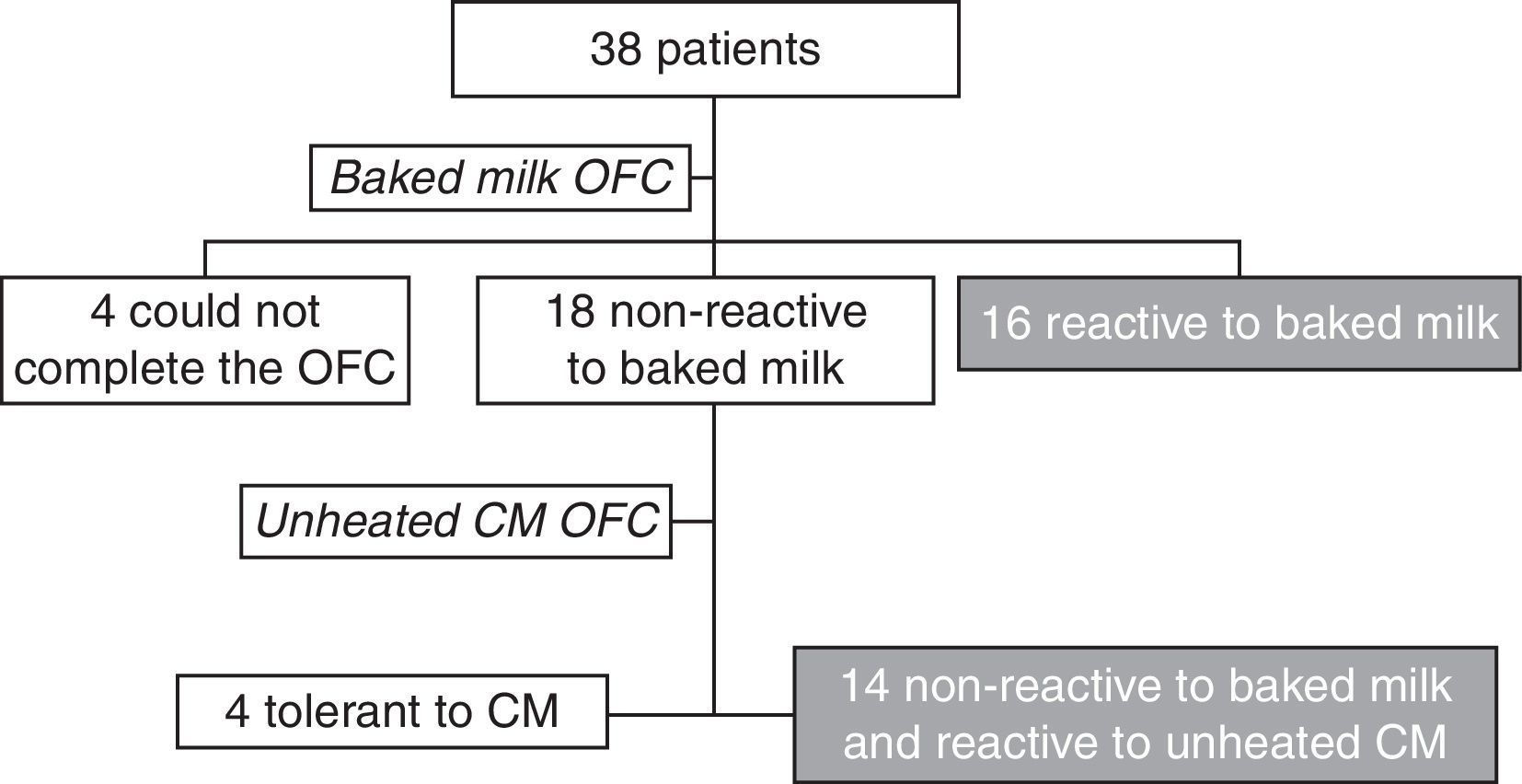

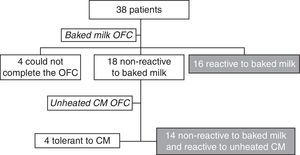

ResultsThe OFC with the muffin was performed with 38 patients from the Food Allergy Center of Instituto da Criança – HCFMUSP – São Paulo. Four of these patients were unable to ingest the whole muffin and were therefore unable to complete the challenge. Another four patients were also excluded from the study because they were tolerant to unheated CM (Fig. 2).

Thirty patients met all the inclusion criteria and presented positive OFC with CM, confirming a current CM allergy. Their median age was seven years and seven months (4 years 10 months to 14 years 2 months), with a mean of eight years (±2 years 6 months); 15 were male (50%). After the OFC with the baked milk product, 16 of the patients were considered reactive and 14 non-reactive to baked milk.

The patients who were reactive to baked milk (n=16; mean age 8 years±2 years 4 months) presented the following symptoms: four experienced an anaphylactic reaction (Grade III) after the first or second quarter of the muffin; five had skin symptoms (urticaria and/or angio-edema); six experienced respiratory symptoms (rhinorrhoea, sneezing, cough and/or wheezing); one had immediate gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain and vomiting). None presented only local reactions, Grade I.28

Fourteen of the patients (46.7%) were non-reactive to baked milk and reactive to unheated CM (mean age 8 years±2 years 10 months). The two patients who had reported an allergic reaction to unintentional milk intake during the past year at home did not undergo the CM OFC. Of the 12 patients who underwent the OFC with CM, seven subjects experienced dermatological symptoms (urticaria and/or angio-edema), three had abdominal symptoms (abdominal pain and vomiting), and two experienced anaphylaxis reactions (Grade III). None presented only local reactions, Grade I. When challenged with fresh CM, seven had symptoms only after ingesting more than 2.8 g of CM protein: five had symptoms with the ingestion of 300 mL and two had symptoms after the ingestion of between 100 and 200mL. Five patients had symptoms with the ingestion of less than 100mL (5–75mL).

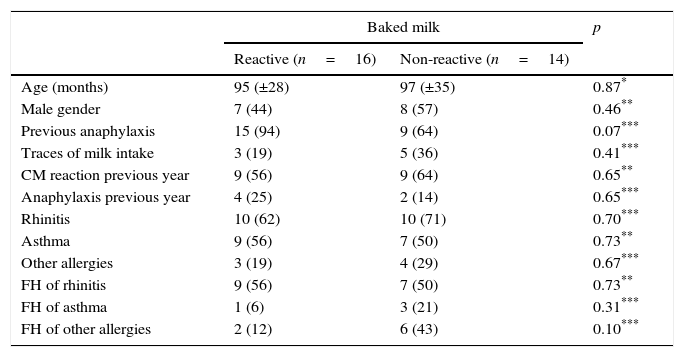

In terms of epidemiological and clinical characteristics, there was no statistically significant difference for age (p=0.87), gender (p=0.46), diagnosis of rhinitis (p=0.70), asthma (p=0.73), history of other allergies (p=0.67), family history of rhinitis (p=0.73), family history of asthma (p=0.31) or family history of other allergies (p=0.10; Table 1).

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics (mean and SD; absolute and percentage frequencies) of reactive and non-reactive to baked milk.

| Baked milk | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive (n=16) | Non-reactive (n=14) | ||

| Age (months) | 95 (±28) | 97 (±35) | 0.87* |

| Male gender | 7 (44) | 8 (57) | 0.46** |

| Previous anaphylaxis | 15 (94) | 9 (64) | 0.07*** |

| Traces of milk intake | 3 (19) | 5 (36) | 0.41*** |

| CM reaction previous year | 9 (56) | 9 (64) | 0.65** |

| Anaphylaxis previous year | 4 (25) | 2 (14) | 0.65*** |

| Rhinitis | 10 (62) | 10 (71) | 0.70*** |

| Asthma | 9 (56) | 7 (50) | 0.73** |

| Other allergies | 3 (19) | 4 (29) | 0.67*** |

| FH of rhinitis | 9 (56) | 7 (50) | 0.73** |

| FH of asthma | 1 (6) | 3 (21) | 0.31*** |

| FH of other allergies | 2 (12) | 6 (43) | 0.10*** |

CM – cow's milk; FH – family history.

Ninety-three percent of the group that was reactive to baked milk reported prior anaphylaxis, while this number was 64% in the group of non-reactive patients, showing no significant difference (p=0.07). Likewise, there was no statistical significance when the two groups were compared in terms of the reported intake of milk traces prior to the OFC (p=0.41). By analysing the data from the patients’ recent history, no difference was identified between the two groups in terms of allergic reactions in the year prior to the test (p=0.65). Twenty-five percent of the reactive group reported anaphylaxis in the year prior to the challenge compared with 14% of the non-reactive group; the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.65). None of the patients presented chronic urticaria, atopic dermatitis or other food allergies (Table 1).

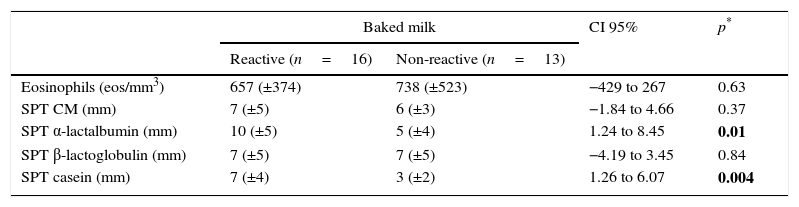

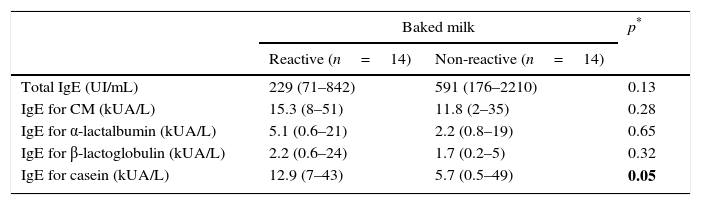

Regarding the laboratory parameters, three patients presented a negative prick test for CM with serum IgE to CM greater than 0.35kUA/L. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the eosinophil blood count (p=0.63) and total IgE (p=0.13). When comparing the prick tests of both groups, there were statistically significant differences for α-lactalbumin (p=0.01) and casein (p=0.004). For serum-specific IgE, a statistically significant difference was only found for casein (p=0.05; Tables 2 and 3).

Laboratorial characteristics (eosinophils and skin prick test) of reactive and non-reactive to baked milk (mean, SD and CI 95%).

| Baked milk | CI 95% | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive (n=16) | Non-reactive (n=13) | |||

| Eosinophils (eos/mm3) | 657 (±374) | 738 (±523) | −429 to 267 | 0.63 |

| SPT CM (mm) | 7 (±5) | 6 (±3) | −1.84 to 4.66 | 0.37 |

| SPT α-lactalbumin (mm) | 10 (±5) | 5 (±4) | 1.24 to 8.45 | 0.01 |

| SPT β-lactoglobulin (mm) | 7 (±5) | 7 (±5) | −4.19 to 3.45 | 0.84 |

| SPT casein (mm) | 7 (±4) | 3 (±2) | 1.26 to 6.07 | 0.004 |

SPT – skin prick test; CM – cow's milk.

Laboratorial characteristics (total IgE and specifics) of reactive and non-reactive to baked milk (median and IQR).

| Baked milk | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive (n=14) | Non-reactive (n=14) | ||

| Total IgE (UI/mL) | 229 (71–842) | 591 (176–2210) | 0.13 |

| IgE for CM (kUA/L) | 15.3 (8–51) | 11.8 (2–35) | 0.28 |

| IgE for α-lactalbumin (kUA/L) | 5.1 (0.6–21) | 2.2 (0.8–19) | 0.65 |

| IgE for β-lactoglobulin (kUA/L) | 2.2 (0.6–24) | 1.7 (0.2–5) | 0.32 |

| IgE for casein (kUA/L) | 12.9 (7–43) | 5.7 (0.5–49) | 0.05 |

CM – cow's milk.

When these patients were evaluated one year after the OFC with baked milk, none of the 16 patients who were reactive to baked milk was ingesting CM, while four (28%) of patients who were non-reactive were ingesting fresh CM without reaction (p=0.037). Of the 14 patients who were non-reactive to baked milk, five presented symptoms after home intake of baked milk products, and none of the symptoms were severe. Only one patient decided to stop consuming baked milk products at home due to abdominal pain.

DiscussionThe relevance of this study was its finding that among the patients with persistent CMA at a food allergy center in the city of São Paulo (Brazil), there were different phenotypes, commensurate with those reported in the literature. It was shown that almost half of the patients, even those who were allergic to CM, could tolerate muffins made with baked milk. This ratio differed from the reports of other studies, which described a baked milk tolerance of between 65% and 83%,13–16 higher than the results reported in the present study. One possible explanation for this difference is the severity of the symptoms related by the patients. It is also important to consider that the baked milk OFC studies reported in the literature included more heterogeneous samples than our study did. By selecting patients over four years old for this study, we reduced the possibility of including younger patients with possible benign and spontaneous evolution of CM tolerance, making the sample more homogeneous. Furthermore, children younger than four years old have more difficulty ingesting a whole muffin, due to lower compliance.

An interesting aspect of this study was that the investigator was unaware of the patients’ clinical and laboratory results prior to the test. It also describes a standardized technique for OFC with a baked milk product that can be easily reproduced in qualified centers. This formula only requires one muffin unit to achieve the desired CM protein amount (2.8g), while other studies have required two units, which increases the time demands.13–15 Other important factors were the organoleptic characteristics of the muffin, which encouraged the patients’ adherence at the time of the test and afterwards, at home.

An important consideration is that the muffin provided in the test had 2.8g of CM protein, while the OFC with unheated milk normally has approximately 10g of protein. It is very difficult to prepare a recipe that concentrates a greater amount of protein in a single product. Therefore, non-reactivity in the OFC with baked milk might be related to the ingestion of small amounts of the antigen. This hypothesis can be corroborated by the findings of our study because in the challenge with unheated CM, 58% of the patients showed a reaction only after ingesting more than 2.8g of CM protein. Another possibility is that the baked milk product had its allergenicity decreased because of the classic Maillard reaction, process between carbohydrates and proteins when submitted to high temperatures, which can modify the structure and allergenicity of the antigens.

All the patients in this study who were non-reactive to baked milk were subsequently challenged with unheated CM to rule out CM tolerance, except for those patients who had demonstrated clinical reactivity to CM in the past year. By assuming CM reactivity through cut-offs for laboratory values (prick test or serum specific IgE) and not using the gold standard method of OFC, we could include patients who were tolerant of that food.

An interesting observation from the study by Nowak-Wegrzyn et al.13 is that no patient who tolerated baked milk presented systemic reactions to the unheated milk challenge, suggesting that this group could react less severely to CM. In contrast, in this study, the presence of anaphylaxis in two patients who were tolerant of baked milk when challenged with CM showed that these patients might experience severe reactions after contact with fresh milk. Thus, when introducing heated milk products into the diet at home, patients and their families must be well advised to continue to exclude fresh CM.

Among the 14 patients who showed no reactivity to baked milk during the OFC, five presented mild or moderate adverse reactions later while eating baked milk products made at home; however, this did not inhibit them from continuing to consume the baked milk products. The reactions may have been the result of insufficient cooking to ensure that the protein's conformation changed, or it may have results from other factors, such as infections, exercise, fasting or the inhalation of the milk product.29

It is important to identify clinical and laboratory markers that could predict whether a patient will tolerate baked milk. Doing so would facilitate the identification of which patients should undergo the OFC. It did not identify a statistically significant difference when comparing the clinical characteristics of the two groups. There are controversies in the literature regarding these aspects. Some studies13,14 found no difference in the characteristics analyzed; however, Mehr et al.16 reported the following clinical predictors of reactivity to baked milk: asthma, asthma requiring preventative therapy, multiple food allergies, and a history of anaphylaxis.

Regarding the laboratory findings, this study identified a statistically significant difference between the reactive and non-reactive groups in the prick test results for α-lactalbumin and casein and for serum IgE specific for casein. This corroborates the findings of the studies by Nowak-Wegrzyn et al.,13 Ford et al.15 and Caubet et al.,30 which showed a statistically significant difference in IgE specific for casein between the groups that were and were not reactive to baked milk. The difference in α-lactalbumin is a specific finding of this study, but its significance is still not clear to us.

The major limitation of the study is the size of the sample. Although studies that aggregate larger numbers of patients are advisable, the need for adequate hospital structure and intense medical monitoring makes their realization difficult. The small sample of this study did not permit an acceptable ROC curve. Therefore, it was difficult to propose cut-off values for the IgE or skin test for cow's milk that were associated with the food challenge outcome.

When the patients were evaluated after one year of OFC, four patients who were non-reactive to baked milk were ingesting fresh CM with no reaction based on medical indications or the reports of the patients and their families. On the other hand, none of the baked milk-reactive patients was ingesting fresh CM and continued to completely exclude it from their diets. Although a new OFC with CM for the two groups was not carried out, this simple comparison showed that somehow the group that was non-reactive to baked milk benefited from introducing baked milk into their diet. We cannot conclude that the consumption of baked milk was the only factor leading to the desensitization of these patients because the results were not compared to those of a control group with the same characteristics. When a patient was considered non-reactive to baked milk, medical staff and family members felt encouraged to expose these patients to increasing amounts of fresh CM at an earlier age. It is important to emphasize that these children should carry epinephrine auto injectors and that their nutritional requirements need to be routinely assessed.31

This study showed that there are different phenotypes among patients over four years old with persistent CMA and that approximately half of them tolerate baked milk. These results suggest that an oral food challenge with baked milk should be considered, always under medical supervision and in the appropriate setting. This test can greatly contribute to changing the follow-up and treatment paradigms of patients with CMA. Tests for casein and α-lactalbumin (prick test and serum-specific IgE) proved to be laboratory markers that can be used to suggest which patients would be more likely to tolerate baked milk, although OFC remains the gold standard for the correct diagnosis of food allergy.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Financial supportNo support was provided.

Authors’ contributionMayra, Cristiane, Andrea, Cleonir and Priscilla are members of the team that executed the oral food challenge and collected patient data, together with the principal author.

Glauce is the nutritionist who developed the recipe.

Ana Paula, Antonio Carlos and Cristina are the professors associated that developed the Project and guided the search.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest.