To describe the profile of people with disabilities who have experienced some form of violence in the northwestern region of Colombia between 2021 and 2023.

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional study based on records from the National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences (INMLCF). All reports of violence against people with disabilities in the departments of Antioquia, Córdoba, and Chocó from 2021 to 2023 were included. Sociodemographic, temporal, spatial, and event-specific variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics and chi-square tests in SPSS software.

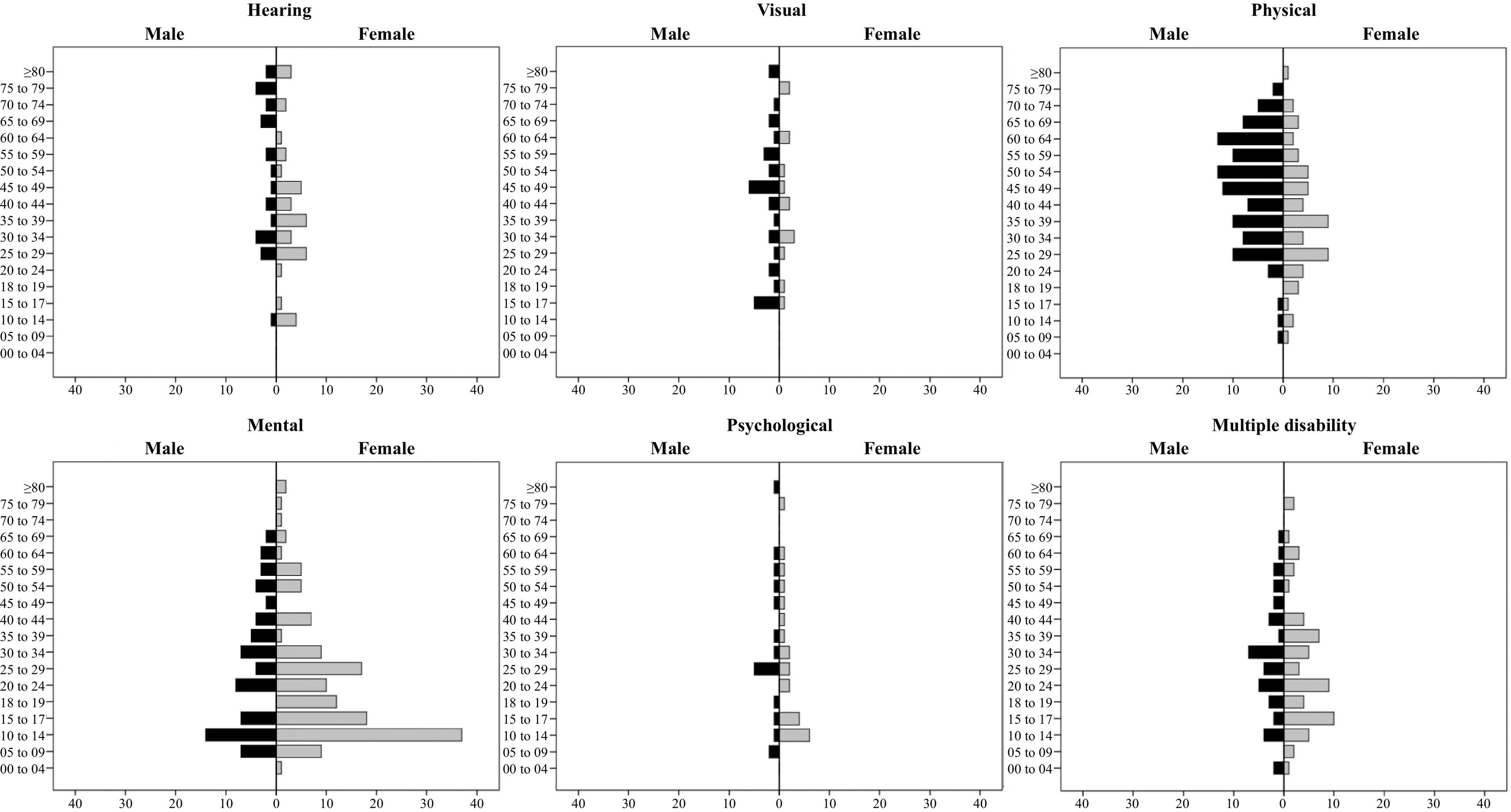

ResultsA total of 503 cases of violence against people with disabilities were identified, with a regional incidence of 1.9 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Women were affected in 56.7% of cases. Women with mental, multiple, and hearing disabilities were the most impacted, while among men, violence was more prevalent in those with visual and physical disabilities. The home was the most common setting for the incidents, and the primary suspected aggressor was a family member.

ConclusionsThis study highlights the vulnerability factors of people with disabilities to various forms of violence and underscores the need for differentiated public policies that address the specificities of this phenomenon. Violence in this group is not only mediated by gender but also by the type of disability and social structure. Greater awareness, preventive strategies, and a comprehensive approach are required to ensure protection and access to justice for these individuals.

Describir el perfil de las personas con discapacidad que han experimentado algún tipo de violencia en la región noroccidental de Colombia entre los años 2021 y 2023.

Materiales y métodosEstudio transversal con registros del Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses (INMLCF). Se incluyeron todos los reportes de violencia en personas con discapacidad en los departamentos de Antioquia, Córdoba y Chocó entre 2021 y 2023. Se analizaron variables sociodemográficas, temporales, espaciales y específicas de los hechos mediante estadística descriptiva y pruebas de chi-cuadrado en el software SPSS.

ResultadosSe identificaron 503 casos de violencia en personas con discapacidad, con una incidencia regional de 1,9 casos por cada 100.000 habitantes. Las mujeres fueron afectadas en el 56,7% de los casos. Las mujeres con discapacidad mental, múltiple y auditiva fueron las más afectadas, mientras que en los hombres prevaleció la violencia en aquellos con discapacidad visual y física. La vivienda fue el escenario más común de los hechos, y el principal presunto agresor fue un familiar.

ConclusionesEste estudio evidencia factores de vulnerabilidad de las personas con discapacidad frente a diversas formas de violencia y resalta la necesidad de políticas públicas diferenciadas que aborden las particularidades de este fenómeno. La violencia en este grupo no solo está mediada por el género, sino también por el tipo de discapacidad y la estructura social. Se requiere mayor sensibilización, estrategias de prevención y un enfoque integral que garantice la protección y el acceso a la justicia para estas personas.

People with disabilities are one of the most marginalised population groups. They are exposed to multiple forms of violence due to factors such as functional dependence, structural discrimination, and limited access to protection and justice services.1–3 They are at greater risk of experiencing violence than people without disabilities, which increases their vulnerability to adverse psychological outcomes such as severe anxiety and depression.4

International studies have identified specific patterns of violence against people with disabilities. In the United States, 70% of people with disabilities have experienced abuse, and 90% have experienced violence on multiple occasions.5 In contrast, people with mental disabilities in countries in Asia and the Middle East have experienced high rates of physical and sexual violence. Deteriorating health and psychiatric disorders were the most common consequences of abuse.6,7 Research in five countries, three in sub-Saharan Africa (Ghana, Rwanda, and South Africa) and two in Asia (Nepal and Afghanistan), found that women with disabilities are at greater risk of all forms of intimate partner violence (physical, sexual, emotional, and economic) than women without disabilities, with the risk increasing proportionally with the degree of disability.8

In Colombia, armed conflict has exacerbated this problem. In 2016, more than 7,860,385 victims of the conflict were reported, with forced displacement having the greatest impact on people with disabilities, with 173,106 cases recorded. When these data were analysed by gender, it was found that men with disabilities had experienced forced displacement at a higher rate.9 In 2020, 15% of people with disabilities reported being victims of armed conflict.10 Currently, epidemiological reports include disability as a sociodemographic variable in studies on violence. However, there is little research that considers the individual with a disability as the unit of analysis.9,11

Classifying violence against this population requires detailed analysis, as significant gaps exist in the information available on the prevalence and risk of violence in population subgroups. While most studies have focused on women with disabilities, other populations with disabilities have received little attention. This hinders the possibility of analysing the phenomenon from an intersectional perspective, which would enable us to understand how different coexisting identities, such as disability, gender, ethnicity, and religion, intersect with systems of oppression and how these interactions can intensify exposure to violence. This approach is necessary in order to recognise the heterogeneity of experiences of violence based on multiple identities and social conditions.12–14

Research in low- and middle-income countries is also lacking, and the quality of information is often poor due to errors in data coding, differences in the classification of disability and the absence of detailed records on specific forms of violence.2,15

In Colombia, for instance, the National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences (INMLCF) is responsible for recording cases of violence. However, it only started including the disability category in its epidemiological reports in 2021. Although Colombia has regulatory frameworks that seek to guarantee the rights of people with disabilities, implementing effective strategies remains challenging, particularly in areas with limited access to protection and justice institutions. Without disaggregated information, it is impossible to accurately assess the impact of violence on persons with disabilities or to design public policies that address their specific needs. Therefore, studies are needed to characterise violence against this population and establish intervention strategies to ensure their protection.

The objective of this study was to describe the profile of persons with disabilities who experienced violence in northwestern Colombia between 2021 and 2023. To this end, the sociodemographic, temporal, spatial, and specific characteristics of the incidents were identified.

Materials and methodsA descriptive, cross-sectional, retrospective design with an analytical approach was employed, based on official INMLCF records. All cases reported in the official records of persons with disabilities who experienced some form of violence in the departments of Antioquia, Córdoba, and Chocó (northwestern Colombia) between 2021 and 2023 were included. Incomplete or inconsistent records were excluded.

The study focused on the northwestern region of Colombia, which represents approximately 11.9% of the national territory. According to official estimates, this region was expected to account for 17.9% of the country's population by 2023.16 Additionally, this region is home to 16.6% of people with disabilities (13.8% in Antioquia, 2.4% in Córdoba, and 0.4% in Chocó). However, it is estimated that there is significant underreporting in the latter department.17,18

Data collection strategyThe annual reports of the INMLCF Regional Reference Centre on Violence were obtained from the Forensic Clinic Information System (SICLICO). The analysed variables included sociodemographic aspects (gender, age in five-year increments, marital status, education, occupation, ethnicity, and status of vulnerability), temporal aspects (year, month, day of the week, and time range), spatial aspects (department, municipality, area and setting where the incident occurred) and specific incident characteristics (activity carried out by the victim, circumstances and context of the incident, causal mechanism, and alleged perpetrator).

Data validation and adjustment consisted of creating a multiple disability category where more than one disability was present, regrouping the education, occupation, setting, activity, circumstances, context, causal mechanism, and alleged perpetrator categories, and normalising the INMLCF-established categories to consolidate the data. The disability type classifications correspond to the labels provided by forensic medicine sources during the study period.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was conducted using absolute and relative frequencies, as well as incidence rates per 100,000 inhabitants (PCMH), at the departmental level. The rates were calculated by using the number of persons with disabilities who experienced a form of violence as the numerator and the population projections made by the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) for the period 2016–2026 as the denominator. Pearson's X2 tests of independence and linear trend were applied to perform the statistical comparison between the type of disability and the other study variables. Multiple comparisons were then made by column as a post hoc analysis to identify statistical differences between categories. A significance level of p < .05 was considered. SPSS version 21 statistical software was used for data processing.

Ethical considerationsIn accordance with Resolution 008430 of 1993 from Colombia's Ministry of Health, this study is classified as risk-free because it is based on secondary sources of information. Consequently, neither approval from an ethics committee nor informed consent was required.

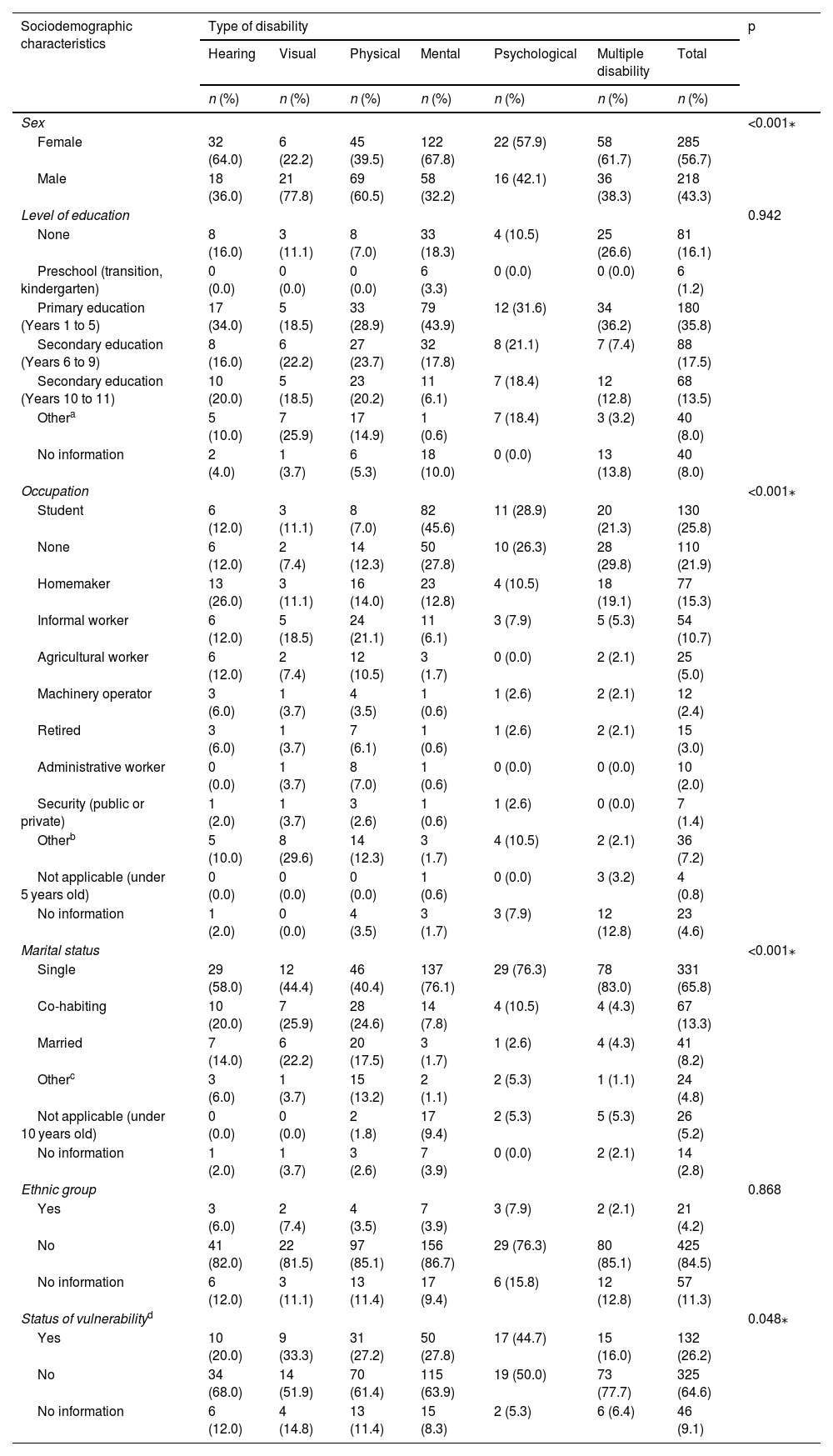

ResultsTable 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of individuals who have experienced violence, categorised by type of disability. During the analysed period, 503 people with disabilities reported experiencing one of the forms of violence addressed by the INMLCF. Of these, 56.7% were women, 28.2% were under 18 years of age, 53.1% had no or low education, and 26.3% had a status of vulnerability (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of persons with some type of disability who were victims of violence. Northwestern region of Colombia, 2021–2023.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Type of disability | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing | Visual | Physical | Mental | Psychological | Multiple disability | Total | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex | <0.001⁎ | |||||||

| Female | 32 (64.0) | 6 (22.2) | 45 (39.5) | 122 (67.8) | 22 (57.9) | 58 (61.7) | 285 (56.7) | |

| Male | 18 (36.0) | 21 (77.8) | 69 (60.5) | 58 (32.2) | 16 (42.1) | 36 (38.3) | 218 (43.3) | |

| Level of education | 0.942 | |||||||

| None | 8 (16.0) | 3 (11.1) | 8 (7.0) | 33 (18.3) | 4 (10.5) | 25 (26.6) | 81 (16.1) | |

| Preschool (transition, kindergarten) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.2) | |

| Primary education (Years 1 to 5) | 17 (34.0) | 5 (18.5) | 33 (28.9) | 79 (43.9) | 12 (31.6) | 34 (36.2) | 180 (35.8) | |

| Secondary education (Years 6 to 9) | 8 (16.0) | 6 (22.2) | 27 (23.7) | 32 (17.8) | 8 (21.1) | 7 (7.4) | 88 (17.5) | |

| Secondary education (Years 10 to 11) | 10 (20.0) | 5 (18.5) | 23 (20.2) | 11 (6.1) | 7 (18.4) | 12 (12.8) | 68 (13.5) | |

| Othera | 5 (10.0) | 7 (25.9) | 17 (14.9) | 1 (0.6) | 7 (18.4) | 3 (3.2) | 40 (8.0) | |

| No information | 2 (4.0) | 1 (3.7) | 6 (5.3) | 18 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (13.8) | 40 (8.0) | |

| Occupation | <0.001⁎ | |||||||

| Student | 6 (12.0) | 3 (11.1) | 8 (7.0) | 82 (45.6) | 11 (28.9) | 20 (21.3) | 130 (25.8) | |

| None | 6 (12.0) | 2 (7.4) | 14 (12.3) | 50 (27.8) | 10 (26.3) | 28 (29.8) | 110 (21.9) | |

| Homemaker | 13 (26.0) | 3 (11.1) | 16 (14.0) | 23 (12.8) | 4 (10.5) | 18 (19.1) | 77 (15.3) | |

| Informal worker | 6 (12.0) | 5 (18.5) | 24 (21.1) | 11 (6.1) | 3 (7.9) | 5 (5.3) | 54 (10.7) | |

| Agricultural worker | 6 (12.0) | 2 (7.4) | 12 (10.5) | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 25 (5.0) | |

| Machinery operator | 3 (6.0) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (3.5) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (2.1) | 12 (2.4) | |

| Retired | 3 (6.0) | 1 (3.7) | 7 (6.1) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (2.1) | 15 (3.0) | |

| Administrative worker | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 8 (7.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (2.0) | |

| Security (public or private) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.4) | |

| Otherb | 5 (10.0) | 8 (29.6) | 14 (12.3) | 3 (1.7) | 4 (10.5) | 2 (2.1) | 36 (7.2) | |

| Not applicable (under 5 years old) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.2) | 4 (0.8) | |

| No information | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.5) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (7.9) | 12 (12.8) | 23 (4.6) | |

| Marital status | <0.001⁎ | |||||||

| Single | 29 (58.0) | 12 (44.4) | 46 (40.4) | 137 (76.1) | 29 (76.3) | 78 (83.0) | 331 (65.8) | |

| Co-habiting | 10 (20.0) | 7 (25.9) | 28 (24.6) | 14 (7.8) | 4 (10.5) | 4 (4.3) | 67 (13.3) | |

| Married | 7 (14.0) | 6 (22.2) | 20 (17.5) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (2.6) | 4 (4.3) | 41 (8.2) | |

| Otherc | 3 (6.0) | 1 (3.7) | 15 (13.2) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (1.1) | 24 (4.8) | |

| Not applicable (under 10 years old) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.8) | 17 (9.4) | 2 (5.3) | 5 (5.3) | 26 (5.2) | |

| No information | 1 (2.0) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (2.6) | 7 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 14 (2.8) | |

| Ethnic group | 0.868 | |||||||

| Yes | 3 (6.0) | 2 (7.4) | 4 (3.5) | 7 (3.9) | 3 (7.9) | 2 (2.1) | 21 (4.2) | |

| No | 41 (82.0) | 22 (81.5) | 97 (85.1) | 156 (86.7) | 29 (76.3) | 80 (85.1) | 425 (84.5) | |

| No information | 6 (12.0) | 3 (11.1) | 13 (11.4) | 17 (9.4) | 6 (15.8) | 12 (12.8) | 57 (11.3) | |

| Status of vulnerabilityd | 0.048⁎ | |||||||

| Yes | 10 (20.0) | 9 (33.3) | 31 (27.2) | 50 (27.8) | 17 (44.7) | 15 (16.0) | 132 (26.2) | |

| No | 34 (68.0) | 14 (51.9) | 70 (61.4) | 115 (63.9) | 19 (50.0) | 73 (77.7) | 325 (64.6) | |

| No information | 6 (12.0) | 4 (14.8) | 13 (11.4) | 15 (8.3) | 2 (5.3) | 6 (6.4) | 46 (9.1) | |

The incidence rate of violence in the northwestern region was 1.9 PCMH, with the highest rate in the department of Antioquia at 2.4 PCMH, followed by Córdoba and Chocó at 0.8 PCMH and 0.6 PCMH, respectively.

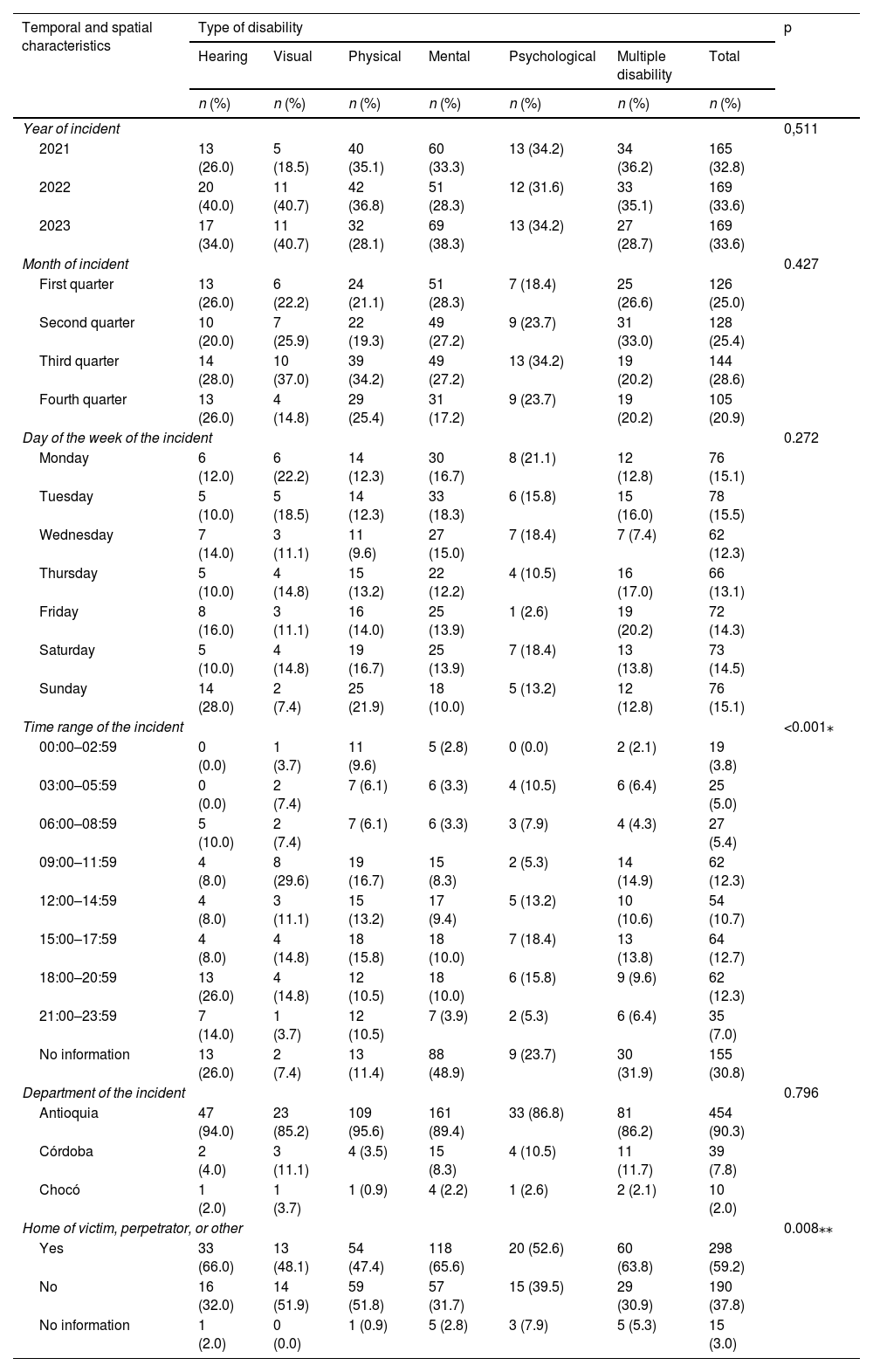

Hearing disabilityOf the people with hearing disabilities who have experienced violence (n = 50), nearly one-third are women, and the most common age range is 25–39 years (40%) (Fig. 1). In terms of other variables, 70.0% have completed basic or secondary education; the most common occupation is homemaker (26.0%); and most are single (58.0%). Only 6.0% identify as Black/Afro-descendant and 20.0% reported some form of vulnerability (Table 1). The reported incidents occurred most frequently in the third quarter of 2022 (28.0%), on Sundays (28.0%), between 6:00 p.m. and 11:59 p.m. (40.0%), and during the year as a whole (40.0%) (Table 2).

Temporal and spatial characteristics of violence against persons with some type of disability. North-western region of Colombia, 2021–2023.

| Temporal and spatial characteristics | Type of disability | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing | Visual | Physical | Mental | Psychological | Multiple disability | Total | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Year of incident | 0,511 | |||||||

| 2021 | 13 (26.0) | 5 (18.5) | 40 (35.1) | 60 (33.3) | 13 (34.2) | 34 (36.2) | 165 (32.8) | |

| 2022 | 20 (40.0) | 11 (40.7) | 42 (36.8) | 51 (28.3) | 12 (31.6) | 33 (35.1) | 169 (33.6) | |

| 2023 | 17 (34.0) | 11 (40.7) | 32 (28.1) | 69 (38.3) | 13 (34.2) | 27 (28.7) | 169 (33.6) | |

| Month of incident | 0.427 | |||||||

| First quarter | 13 (26.0) | 6 (22.2) | 24 (21.1) | 51 (28.3) | 7 (18.4) | 25 (26.6) | 126 (25.0) | |

| Second quarter | 10 (20.0) | 7 (25.9) | 22 (19.3) | 49 (27.2) | 9 (23.7) | 31 (33.0) | 128 (25.4) | |

| Third quarter | 14 (28.0) | 10 (37.0) | 39 (34.2) | 49 (27.2) | 13 (34.2) | 19 (20.2) | 144 (28.6) | |

| Fourth quarter | 13 (26.0) | 4 (14.8) | 29 (25.4) | 31 (17.2) | 9 (23.7) | 19 (20.2) | 105 (20.9) | |

| Day of the week of the incident | 0.272 | |||||||

| Monday | 6 (12.0) | 6 (22.2) | 14 (12.3) | 30 (16.7) | 8 (21.1) | 12 (12.8) | 76 (15.1) | |

| Tuesday | 5 (10.0) | 5 (18.5) | 14 (12.3) | 33 (18.3) | 6 (15.8) | 15 (16.0) | 78 (15.5) | |

| Wednesday | 7 (14.0) | 3 (11.1) | 11 (9.6) | 27 (15.0) | 7 (18.4) | 7 (7.4) | 62 (12.3) | |

| Thursday | 5 (10.0) | 4 (14.8) | 15 (13.2) | 22 (12.2) | 4 (10.5) | 16 (17.0) | 66 (13.1) | |

| Friday | 8 (16.0) | 3 (11.1) | 16 (14.0) | 25 (13.9) | 1 (2.6) | 19 (20.2) | 72 (14.3) | |

| Saturday | 5 (10.0) | 4 (14.8) | 19 (16.7) | 25 (13.9) | 7 (18.4) | 13 (13.8) | 73 (14.5) | |

| Sunday | 14 (28.0) | 2 (7.4) | 25 (21.9) | 18 (10.0) | 5 (13.2) | 12 (12.8) | 76 (15.1) | |

| Time range of the incident | <0.001⁎ | |||||||

| 00:00–02:59 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 11 (9.6) | 5 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 19 (3.8) | |

| 03:00–05:59 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | 7 (6.1) | 6 (3.3) | 4 (10.5) | 6 (6.4) | 25 (5.0) | |

| 06:00–08:59 | 5 (10.0) | 2 (7.4) | 7 (6.1) | 6 (3.3) | 3 (7.9) | 4 (4.3) | 27 (5.4) | |

| 09:00–11:59 | 4 (8.0) | 8 (29.6) | 19 (16.7) | 15 (8.3) | 2 (5.3) | 14 (14.9) | 62 (12.3) | |

| 12:00–14:59 | 4 (8.0) | 3 (11.1) | 15 (13.2) | 17 (9.4) | 5 (13.2) | 10 (10.6) | 54 (10.7) | |

| 15:00–17:59 | 4 (8.0) | 4 (14.8) | 18 (15.8) | 18 (10.0) | 7 (18.4) | 13 (13.8) | 64 (12.7) | |

| 18:00–20:59 | 13 (26.0) | 4 (14.8) | 12 (10.5) | 18 (10.0) | 6 (15.8) | 9 (9.6) | 62 (12.3) | |

| 21:00–23:59 | 7 (14.0) | 1 (3.7) | 12 (10.5) | 7 (3.9) | 2 (5.3) | 6 (6.4) | 35 (7.0) | |

| No information | 13 (26.0) | 2 (7.4) | 13 (11.4) | 88 (48.9) | 9 (23.7) | 30 (31.9) | 155 (30.8) | |

| Department of the incident | 0.796 | |||||||

| Antioquia | 47 (94.0) | 23 (85.2) | 109 (95.6) | 161 (89.4) | 33 (86.8) | 81 (86.2) | 454 (90.3) | |

| Córdoba | 2 (4.0) | 3 (11.1) | 4 (3.5) | 15 (8.3) | 4 (10.5) | 11 (11.7) | 39 (7.8) | |

| Chocó | 1 (2.0) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (2.2) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (2.1) | 10 (2.0) | |

| Home of victim, perpetrator, or other | 0.008⁎⁎ | |||||||

| Yes | 33 (66.0) | 13 (48.1) | 54 (47.4) | 118 (65.6) | 20 (52.6) | 60 (63.8) | 298 (59.2) | |

| No | 16 (32.0) | 14 (51.9) | 59 (51.8) | 57 (31.7) | 15 (39.5) | 29 (30.9) | 190 (37.8) | |

| No information | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 5 (2.8) | 3 (7.9) | 5 (5.3) | 15 (3.0) | |

Of the total number of people with a visual disability (n = 27), 77.8% are male, with the largest age group being 45–49 years old (18.5%) (Fig. 1). Additionally, 59.2% have completed primary or secondary education, and the majority informal workers (18.5%) or single (44.4%). Of these people, 7.4% identify as Black/Afro-descendant and one third report a status of vulnerability (Table 1). In terms of when the incident occurred, most occurred in the third quarter of 2022 and 2023 (40.7% each) and on Mondays (22.2%). The majority of incidents occurred between 9:00 and 11:59 a.m. (29.6%) (Table 2).

Physical disabilityWith regard to physical disability (n = 114), 60.5% of those affected by violence were men, with 41.3% being young adults (aged 18–40) (Fig. 1). Most had completed basic or secondary education (72.8%), worked informally (21.1%), and were single (40.4%). 3.5% identified as Black/Afro-descendant, and 27.2% reported a status of vulnerability (Table 1). The highest number of incidents were recorded in 2021 and 2022 (35.1% and 36.8% respectively), while the most frequent month, day, and time of day were the third quarter of the year (34.2%), Sunday (21.9%), and between 9:00 and 11:59 am (16.7%) (Table 2).

Mental disabilityAmong the people with mental disabilities (n = 180), 67.8% are women, with the largest age group being 10–17 years old (40.0%) (Fig. 1). In terms of other variables, 71.1% have received a basic or secondary education, 45.6% are students, and three-quarters of them are single. Of these people, 3.9% identify with a specific ethnic group and 27.8% reported a status of vulnerability (Table 1). The majority of cases occurred in the first quarter of 2023 (38.3%), with Mondays (16.7%) and Tuesdays (18.3%) being the most frequent days, and the most common time range being between 3:00 p.m. and 8:59 p.m. (20.0%) (Table 2).

Psychological disabilityOf the 38 people with psychological disabilities, 57.9% were women, and the most common age ranges were as follows: 10–14, 15–17, and 25–29 years (Fig. 1). Of these people, 71.1% have basic or secondary education, 28.9% are students, and 76.3% are single. Similarly, 7.9% identified as Black/Afro-descendant, and 44.7% reported a status of vulnerability (Table 1). The highest percentage of cases was recorded in 2021 and 2023 (34.2% in both years), with the highest frequency of incidents occurring in the third quarter (34.2%). The only day of the week with a figure above 20% was Monday, with the highest figures occurring between 12:00 and 20:59 (47.4%) (Table 2).

Multiple disabilityOf the people with multiple disabilities (n = 94), 61.7% are women, with more than half aged between 15 and 34 (52.1%) (Fig. 1). In terms of other variables, 56.4% have a basic or secondary level of education, 29.8% are unemployed and 83.0% are single. Additionally, 2.1% identify as Black/Afro-descendant and 16.0% reported a status of vulnerability (Table 1). In terms of when the incident occurred, the highest percentage of cases was reported in the second quarter of 2021 (33.0%), followed by the first quarter (27.8%) and the fourth quarter (26.8%). Fridays (20.2%), Thursdays (17.0%) and Tuesdays (16.0%) saw the highest number of cases (Table 2).

For all the types of disability, the home was the main setting for violence, accounting for up to 66.0% of cases among people with hearing and mental disabilities (Table 2).

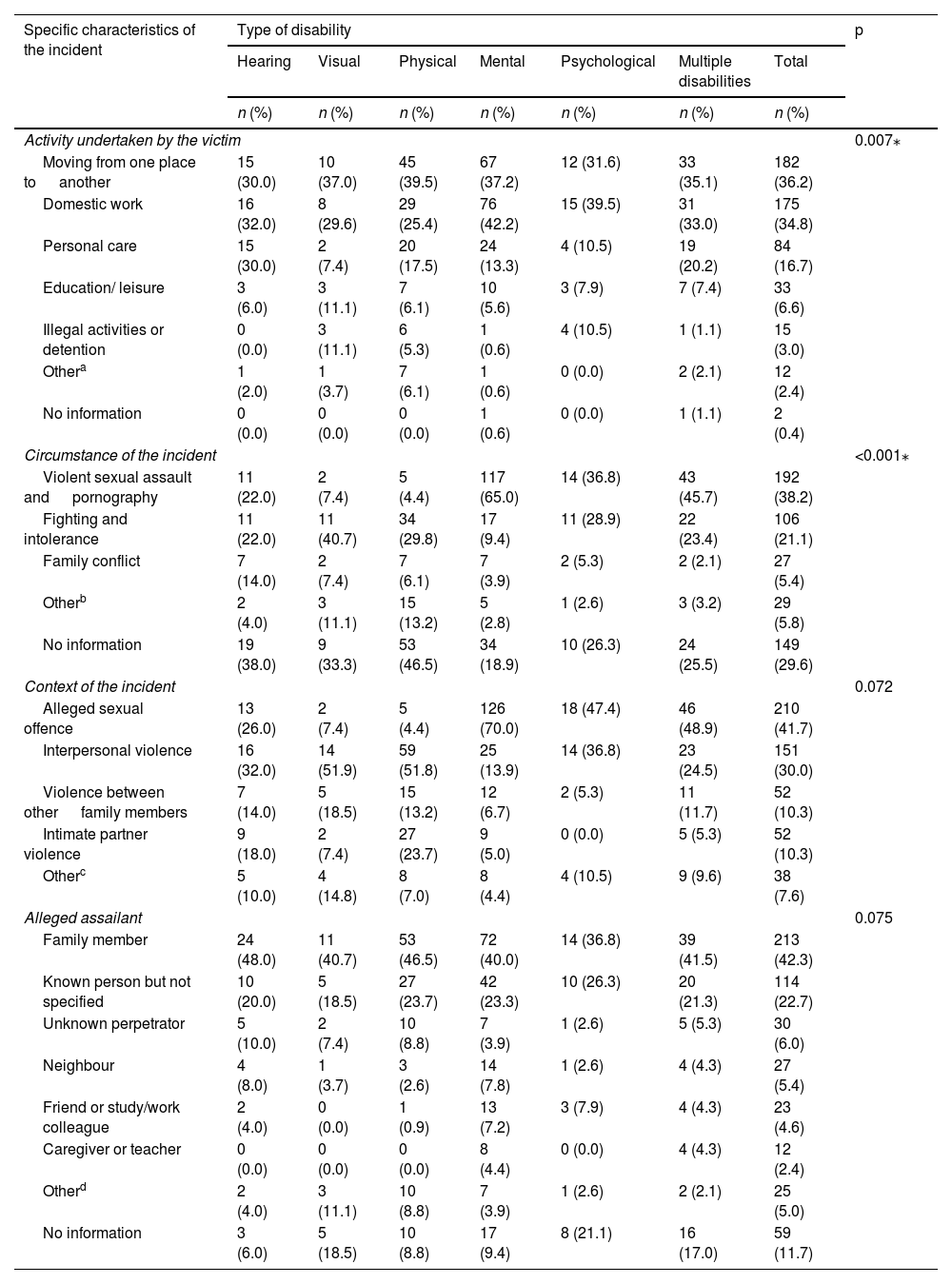

Specific characteristics of the incidentAt the time of the incident, the most frequent activity was travelling from one place to another (39.5%). The circumstances of the incident varied according to the type of disability. Among people with mental (65%), multiple (45.7%), and psychological (36.8%) disabilities, violent sexual assault and pornography were predominant. Among individuals with visual and physical disabilities, fighting and intolerance were more prevalent (40.7% and 29.8%, respectively) (Table 3). In cases involving visual, physical, and hearing disabilities, blunt force impact was the most frequent traumatic mechanism (up to 60.5%), with multiple trauma being the most common diagnosis (up to 74.1%).

Specific characteristics of the incidence of violence against persons with some type of disability. Northwestern region of Colombia, 2021–2023.

| Specific characteristics of the incident | Type of disability | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing | Visual | Physical | Mental | Psychological | Multiple disabilities | Total | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Activity undertaken by the victim | 0.007⁎ | |||||||

| Moving from one place to another | 15 (30.0) | 10 (37.0) | 45 (39.5) | 67 (37.2) | 12 (31.6) | 33 (35.1) | 182 (36.2) | |

| Domestic work | 16 (32.0) | 8 (29.6) | 29 (25.4) | 76 (42.2) | 15 (39.5) | 31 (33.0) | 175 (34.8) | |

| Personal care | 15 (30.0) | 2 (7.4) | 20 (17.5) | 24 (13.3) | 4 (10.5) | 19 (20.2) | 84 (16.7) | |

| Education/ leisure | 3 (6.0) | 3 (11.1) | 7 (6.1) | 10 (5.6) | 3 (7.9) | 7 (7.4) | 33 (6.6) | |

| Illegal activities or detention | 0 (0.0) | 3 (11.1) | 6 (5.3) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (10.5) | 1 (1.1) | 15 (3.0) | |

| Othera | 1 (2.0) | 1 (3.7) | 7 (6.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 12 (2.4) | |

| No information | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Circumstance of the incident | <0.001⁎ | |||||||

| Violent sexual assault and pornography | 11 (22.0) | 2 (7.4) | 5 (4.4) | 117 (65.0) | 14 (36.8) | 43 (45.7) | 192 (38.2) | |

| Fighting and intolerance | 11 (22.0) | 11 (40.7) | 34 (29.8) | 17 (9.4) | 11 (28.9) | 22 (23.4) | 106 (21.1) | |

| Family conflict | 7 (14.0) | 2 (7.4) | 7 (6.1) | 7 (3.9) | 2 (5.3) | 2 (2.1) | 27 (5.4) | |

| Otherb | 2 (4.0) | 3 (11.1) | 15 (13.2) | 5 (2.8) | 1 (2.6) | 3 (3.2) | 29 (5.8) | |

| No information | 19 (38.0) | 9 (33.3) | 53 (46.5) | 34 (18.9) | 10 (26.3) | 24 (25.5) | 149 (29.6) | |

| Context of the incident | 0.072 | |||||||

| Alleged sexual offence | 13 (26.0) | 2 (7.4) | 5 (4.4) | 126 (70.0) | 18 (47.4) | 46 (48.9) | 210 (41.7) | |

| Interpersonal violence | 16 (32.0) | 14 (51.9) | 59 (51.8) | 25 (13.9) | 14 (36.8) | 23 (24.5) | 151 (30.0) | |

| Violence between other family members | 7 (14.0) | 5 (18.5) | 15 (13.2) | 12 (6.7) | 2 (5.3) | 11 (11.7) | 52 (10.3) | |

| Intimate partner violence | 9 (18.0) | 2 (7.4) | 27 (23.7) | 9 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (5.3) | 52 (10.3) | |

| Otherc | 5 (10.0) | 4 (14.8) | 8 (7.0) | 8 (4.4) | 4 (10.5) | 9 (9.6) | 38 (7.6) | |

| Alleged assailant | 0.075 | |||||||

| Family member | 24 (48.0) | 11 (40.7) | 53 (46.5) | 72 (40.0) | 14 (36.8) | 39 (41.5) | 213 (42.3) | |

| Known person but not specified | 10 (20.0) | 5 (18.5) | 27 (23.7) | 42 (23.3) | 10 (26.3) | 20 (21.3) | 114 (22.7) | |

| Unknown perpetrator | 5 (10.0) | 2 (7.4) | 10 (8.8) | 7 (3.9) | 1 (2.6) | 5 (5.3) | 30 (6.0) | |

| Neighbour | 4 (8.0) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (2.6) | 14 (7.8) | 1 (2.6) | 4 (4.3) | 27 (5.4) | |

| Friend or study/work colleague | 2 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 13 (7.2) | 3 (7.9) | 4 (4.3) | 23 (4.6) | |

| Caregiver or teacher | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.3) | 12 (2.4) | |

| Otherd | 2 (4.0) | 3 (11.1) | 10 (8.8) | 7 (3.9) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (2.1) | 25 (5.0) | |

| No information | 3 (6.0) | 5 (18.5) | 10 (8.8) | 17 (9.4) | 8 (21.1) | 16 (17.0) | 59 (11.7) | |

Categories such as: activities related to paid work and activities related to public demonstrations (marches, protests, among others).

Categories such as abuse of authority; criminal gang activity; military action; animal attacks; threats or intimidation; disobeying traffic regulations; theft or attempted theft; unintentional self-harm; jealousy; armed conflict; physical or mental illness; transport incidents; harassment; accidental injury; pedestrians; lawful detention; and socio-political violence.

With regard to the alleged perpetrator, between 78.1% (physical disability) and 93.3% (mental disability) of cases involved men, in most cases, the perpetrator was a family member, although in cases of hearing and physical disability, the spouse or ex-spouse was most frequently identified (37.5% and 47.2%, respectively).

Related factorsSupplementary Table 1 shows that cases of violence against persons with mental disabilities were significantly higher than against those with other types of disabilities. Compared to persons with visual and physical disabilities, differences were found in variables such as gender (women, p < .05), age range (10 to 14 years, p < .05), occupation (student, p < .05), marital status (single, p < .05), and circumstances of the incident (violent sexual assault and pornography, p < .05). Compared to people with hearing and multiple disabilities, differences were mainly observed in occupation (student, p < .05) and circumstances of the incident (violent sexual assault and pornography, p < .05). Compared to people with psychological disabilities, differences were only found in the circumstances of the incident (violent sexual assault and pornography, p < .05).

Cases of violence against people with physical disabilities, the second most frequent, showed significant differences compared to cases involving people with mental disabilities in variables such as gender (men, p < .05), age range (10–14 and 15–17 years, p < .05), occupation (informal workers, agricultural and administrative workers, p < .05), marital status (cohabiting and married, p < .05), and circumstances of the incident (fighting and intolerance, p < .05).

DiscussionTo the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Colombia to develop a sociodemographic profile of persons with disabilities who have experienced some form of violence, differentiated by type of disability. It focused on the northwestern region between 2021 and 2023, due to the availability of data.

The findings show that women with hearing, mental, and multiple disabilities are more exposed to violence, while among men, cases involving people with visual and physical disabilities stand out. These results are consistent with studies that have documented greater exposure to violence—mainly sexual and intimate partner violence—among women with disabilities, particularly those with mental or psychological disabilities.6,19,20 Similarly, a study conducted in New Zealand reported that women with psychological and physical disabilities experienced more cases of sexual violence, while men with physical, mental, and psychological disabilities were more exposed to physical violence outside the intimate partner relationship.6

In contrast, a systematic review found that, although nearly 60% of persons with mental disabilities experienced some form of intimate partner violence, no significant differences were observed between men and women (60% vs. 57%). However, emotional violence was slightly more common among women.21

In terms of age group, violence against people with mental disabilities was most prevalent among those under 35, with the 10–14 age group being the most affected. In contrast, cases of physical disability were most prevalent among adults and older adults. In all types of disability, a higher proportion of single people, those with low levels of education or in vulnerable employment situations were observed, findings that are consistent with other studies.7,19 Most people did not identify with any ethnic group or report any of the vulnerability factors considered by the INMLCF.

It should be noted that the main setting for violence is the home of the victim, the home of the perpetrator, or another home. In line with other studies, this study shows that men continue to be the main perpetrators, and are mostly family members. Few studies have identified women as perpetrators, except in cases of child neglect and abandonment.6,7,19 In several countries, assaults are usually committed by people known to or linked to the victim, but in cases of sexual violence or those involving adult males, the perpetrators are often strangers.6,7,19 This evidence highlights that, although the family environment should be a place of care and protection, it can represent a greater risk for people with disabilities, especially women and minors.

In short, the results show that mental disability is associated with a significantly different victimisation profile than other types of disability. Specifically, it is linked to greater exposure to sexual violence among young women (especially between the ages of 10 and 14), many of whom are students and unmarried. This contrasts with physical disability—the second most common type of disability—where violence affects more adolescent or young adult men in contexts of interpersonal conflict, such as fights or violence associated with alcohol consumption, and with informal or rural occupations. These results are consistent with international evidence, which highlights how sociodemographic and contextual factors vary in their association with acts of violence and the type of disability. In countries such as Brazil and Thailand, people with mental and physical disabilities were found to be significantly more exposed to physical violence in the 10–19 and 20–59 age groups, as were single people.19,22 Similarly, a study conducted in Uganda found that intimate partner violence against persons with any type of disability is more prevalent among individuals over 35 years of age.20

The results of this study suggest that violence against disabled people cannot be understood in isolation. In such situations, various forms of discrimination intersect, including those based on age, gender, and educational level. As van der Heijden et al.23 point out, the social stigma associated with disability can lead to victims being more exposed to violence and dehumanisation. Therefore, an intersectional approach must be adopted that considers not only the type of disability and gender but also age, sexual orientation, and ethnicity, as these factors can amplify or modify the risks and manifestations of violence.

Efforts in Colombia to protect the rights of this group predate the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.24 Legally, Colombia guarantees the rights and protection of all persons, “especially those who, due to their economic, physical or mental condition, are in a situation of manifest weakness”,25 and has established measures to eliminate all forms of discrimination on the basis of disability (Statutory Law 1618 of 2013). The country has also implemented policies, resources and differential actions to promote the recognition of persons with disabilities as subjects of law, through dignified treatment and the prevention of all forms of abuse or violence in family, community, and institutional settings.26–28 Nevertheless, much remains to be done to ensure the effective protection of the rights of this group. One pending task is to decouple vulnerability as an inherent factor from persons with disabilities, understanding it instead as the result of socio-historical and cultural processes. Similarly, there is an urgent need to effectively implement policies aimed at preventing violence against this population, considering the particularities of different contexts and the weak institutional framework in some territories. In rural regions or areas with weak institutional capacity, such as Chocó, it is essential to ensure the territorial deployment of institutions responsible for caring for and protecting victims. It is also necessary to improve accessible and inclusive reporting channels, promote community awareness campaigns, and establish local care networks involving social organisations with intersectional approaches.

Limitations of the studyThis study has some limitations inherent to its cross-sectional design. This prevents the establishment of causal relationships between the analysed variables, limiting the results to descriptive associations at a specific point in time. Additionally, potential underreporting biases were identified, particularly in departments such as Chocó, where geographical, structural, and sociocultural barriers could restrict access to reporting mechanisms and institutional care. This could result in an incomplete representation of the phenomenon in this subregion and lead to an underestimation of its actual magnitude.

While the INMLCF has produced annual reports on violence since 2015, the timeframe of this study's analysis is limited as data including the disability variable were only available from 2021 onwards. Furthermore, access to data at the time of this study depended on the response of regional authorities, making analysis at the national level difficult.

Figures on the prevalence of disability in Colombia are inconsistent. According to DANE, 7.1% of the population has a disability, whereas the Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares (Large Integrated Household Survey) reports 5.1%, and the Ministry of Health reports 2.6%.10,17 These discrepancies make it difficult to identify the actual population of people with disabilities for study.

Furthermore, the disability categories in the INMLCF reports are not clearly defined, which makes comparisons with other studies difficult. In particular, the lack of precise definitions for the categories of mental and psychological disability is problematic, as this can affect both data recording and the interpretation of results. These categories should be revised for future studies. Finally, this research does not enable us to determine whether disability was a motivating factor in violence, nor whether an individual has experienced violence on multiple occasions.

ConclusionsThe findings of this study show that people with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to various forms of violence, depending on the type of disability. Women with mental, multiple, or hearing disabilities experience the highest rates of sexual violence, while individuals with visual or physical disabilities are more likely to be victims of interpersonal and intimate partner violence. The home is recognised as the main setting for these incidents, highlighting the need to strengthen protection measures within families and communities.

These results emphasise the need for differentiated prevention and care strategies that consider the specific characteristics of each type of disability. Improving access to legal protection mechanisms, training professionals to deal with these cases, and promoting effective support networks is vitally important. Furthermore, future research should examine the relationship between economic dependence, barriers to reporting, and the recurrence of violence against this group, with the aim of generating more effective interventions and ensuring the comprehensive protection of persons with disabilities.

Authors' contributionThe authors declare that they were all responsible for: the conception and design of the study, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation; the draft article and critical review of the intellectual content; and final approval of the version presented.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: García-Toro M, Vargas-Alzate CA. Violence against people with disabilities: Profile in the northwestern region of Colombia, 2021–2023. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reml.2025.500476.