Less than lethal weapons (LLW) are devices used to produce pain or inability with less risk of death. This study focuses on lesions caused by less than lethal weapons in Colombia between 2017 and 2021, by using data from Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses (INMLCF).

Materials and methodsA retrospective cross-sectional descriptive study was carried out based on the review of clinical records and medical-legal autopsies of the INMLCF.

ResultsWere found 4,900 cases, revealing that the majority of victims were young men, mainly affected by police batons and kinetic impact projectiles. The most common injuries were ecchymosis and wounds on the extremities and face, and five deaths related to the use of less lethal weapons were documented.

ConclusionsThe findings highlight the need for greater regulation and training in the use of LLW due to its potential to cause serious and fatal injuries.

Las armas menos letales (AML) son dispositivos usados para producir dolor o incapacidad con menor riesgo de letalidad. Este estudio analiza las lesiones causadas por armas menos letales en Colombia entre 2017 y 2021, utilizando datos del Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses (INMLCF).

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio descriptivo, de corte transversal y retrospectivo, basado en la revisión de expedientes clínicos y de necropsias médico legales del INMLCF.

ResultadosSe encontraron 4.900 casos, revelando que la mayoría de las víctimas fueron hombres jóvenes, principalmente afectados por porras policiales y proyectiles de impacto cinético. Las lesiones más comunes fueron equimosis y heridas en las extremidades y la cara. Se documentaron 5 muertes relacionadas con el uso de armas menos letales.

ConclusionesLos hallazgos destacan la necesidad de una mayor regulación y capacitación en el uso de AML debido a su potencial de causar lesiones graves y letales.

Less-than-lethal weapons (LLWs), formerly known as non-lethal weapons, are described as devices or weapons designed to control a group or mass of people, causing physical pain or discomfort and thus neutralising individuals. However, improper use of such weapons can cause death.1–3

The origin of less-than-lethal weapons can be traced back to the tonfa, a hardwood cane used by peasants in Okinawa, Japan, in the 13th century. In the 20th century, this instrument was adapted by an American officer into the modern police baton.4 Throughout the same century, the arsenal of less-than-lethal weapons spread across various countries, including the use of chemical agents, flash-bang grenades, and plastic or rubber bullets.5

Their use by authorities has been suggested as a measure to maintain public order and protect life in circumstances requiring moderate force to prevent, delay, or control hostile acts, when the use of firearms is inappropriate.1

According to the United Nations,1 these weapons can be classified into seven categories:

- •

Police batons: This is the most common weapon. It was specifically designed to provide police officers with a means of self-protection against assault.

- •

Chemical irritants: These are considered defensive agents and include pepper spray and irritants used at a distance, such as tear gas.

- •

Electrically conductive weapons: These are designed to produce neuromuscular incapacitation. Commonly known as “tasers.”

- •

Kinetic impact projectiles: These are made of rubber or plastic.

- •

Dazzling weapons: These are capable of temporarily blinding; they include lasers and light-emitting diodes.

- •

Acoustic weapons: These are devices that emit sounds at high levels that can cause pain and disorientation.

- •

Water cannon: This consists of a vehicle with a cannon that can fire pressurised water.

Detailed statistics on their use and injuries are not yet available internationally for all categories; However, kinetic impact projectiles are the most frequently reported in systematic reviews. In Colombia, there are no publications that have addressed this issue, despite the existence of journalistic reports on their use.

As a result, personal injury assessments and forensic autopsies in cases of violent deaths were studied. Using expert reports prepared by the National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences (INMLCF) in Colombia. This study aimed to understand the injuries caused by the use of less-than-lethal weapons nationwide, characterise the affected population, and determine which less-than-lethal weapons were most commonly used in the country.

Materials and methodsA descriptive, cross-sectional, and retrospective study was conducted based on a review of cases related to the use of less-than-lethal weapons handled by the INMLCF (National Institute of Medical and Forensic Pathology) in Colombia, from January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2021.

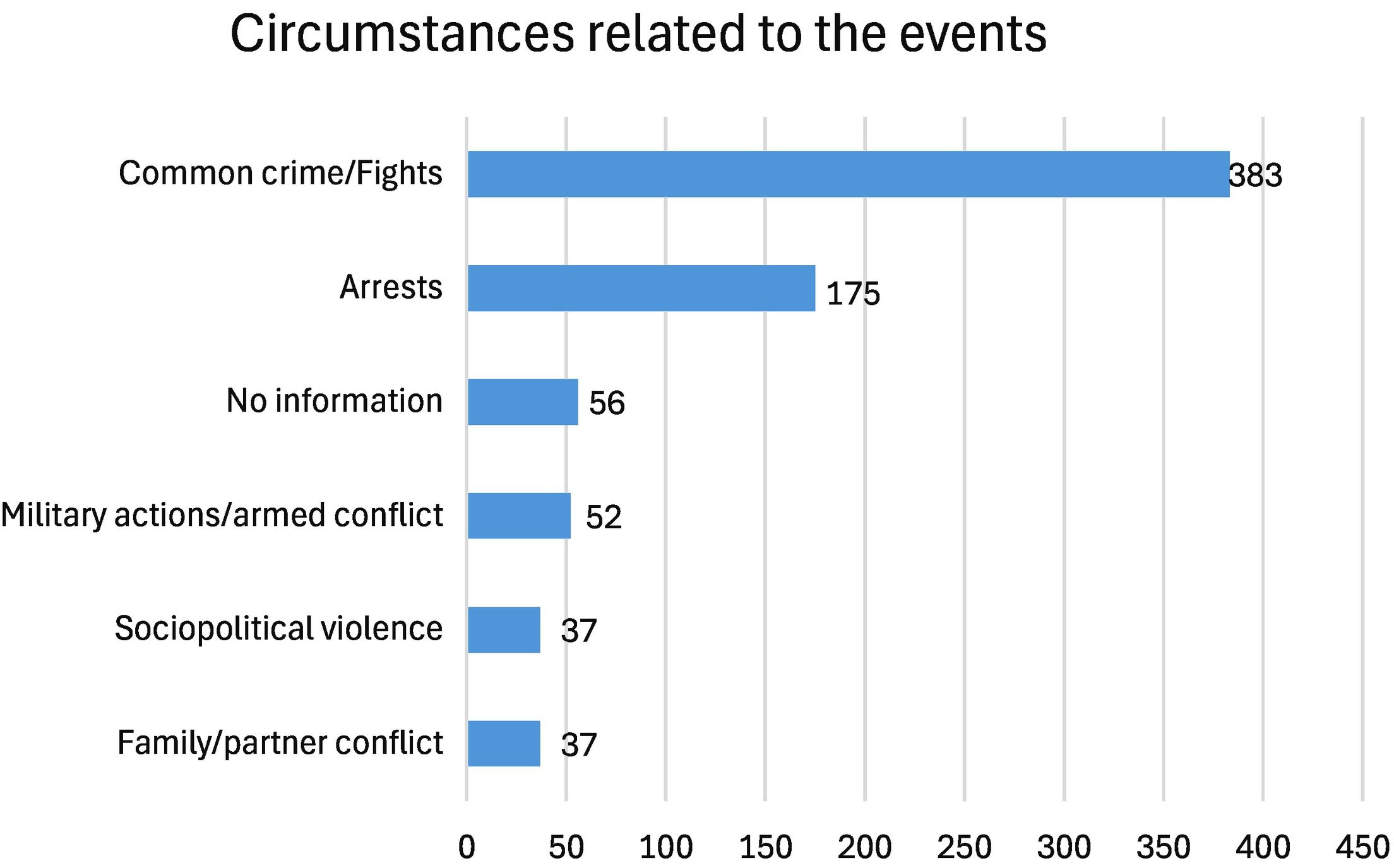

For the review, a keyword search was conducted in the INMLCF's information systems. Using the resulting database, the study's inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) were applied to all cases, and they were classified according to the defined LLW category (dazzling and acoustic weapons were grouped into a single category). Regarding the category of injuries caused by police batons, due to the number of cases, proportional stratified random sampling was applied, using the years of the events as strata.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for cases of interest in the areas of pathology and forensic pathology.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: Prepared by the authors. INMLCF: Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences; LLWs: less-lethal weapons; SICLICO: Forensic Clinical Information System of Colombia; SIRDEC: Missing Persons and Corpses Network Information System.

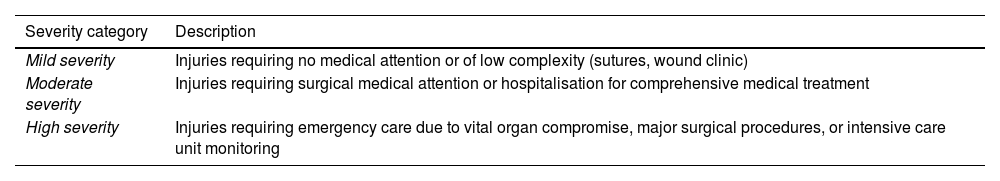

Sociodemographic variables, the context of the events, and the characteristics of the characterised injuries were taken directly from the records provided by each expert, with the exception of the injury severity variable. This variable was determined according to the classification proposed by the authors (Table 2). For forensic pathology cases, a specific description was provided for each case.

Criteria for categorising injury severity in forensic clinical practice.

| Severity category | Description |

|---|---|

| Mild severity | Injuries requiring no medical attention or of low complexity (sutures, wound clinic) |

| Moderate severity | Injuries requiring surgical medical attention or hospitalisation for comprehensive medical treatment |

| High severity | Injuries requiring emergency care due to vital organ compromise, major surgical procedures, or intensive care unit monitoring |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Data processing was performed using Microsoft Excel® for Microsoft 365 MSO (version 2204). Univariate descriptive statistical techniques were applied for the analysis of the general population and each subgroup according to the determined LLW category.

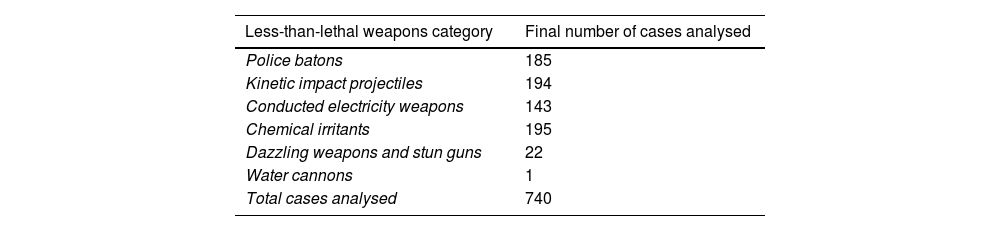

ResultsIn the forensic clinic area, it was found that from January 2017 to December 2021, 17,695 assessments were made for injuries associated with the alleged use of a less-than-lethal weapon. After excluding cases in which no LLWs were involved, in which the type of less-than-lethal weapon used could not be established, or in which information on other variables was incomplete, the number of cases was reduced to 4900.

Table 3 shows the distribution of cases by LLW category after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, along with the cases resulting from sampling for the police baton category.

Total number of cases analysed by less-lethal weapon category.

| Less-than-lethal weapons category | Final number of cases analysed |

|---|---|

| Police batons | 185 |

| Kinetic impact projectiles | 194 |

| Conducted electricity weapons | 143 |

| Chemical irritants | 195 |

| Dazzling weapons and stun guns | 22 |

| Water cannons | 1 |

| Total cases analysed | 740 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

For all categories analysed (740 cases), 79% of the users evaluated were men, 97.5% of the evaluations were performed on Colombians, with an age range from one to 87 years, and an average of 30.2 years.

Regarding the temporal evolution of LLW injuries, their upward trend is striking, with a decrease in 2020, possibly associated with mobility restrictions and mandatory confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by a peak in 2021, when 32.8% of all forensic clinical evaluations were submitted (Fig. 1).

Other data related to time of year showed that the majority of assessments were conducted in May (11.6%), followed by July (10.4%) and September (10.1%). Similarly, it is evident that LLW injuries were most frequent during night-time hours, that is, between 6:00 PM and 11:59 PM (38.2%), followed by the afternoon hours, between 12:00 PM and 5:59 PM (22.8%).

Regarding the analysis of variables by location, it was evident that the majority of cases occurred in municipal capitals (96.7%), and the departments with the highest incidence of cases were Huila, San Andrés, Providencia, and Cauca, with rates per 100,000 inhabitants of 3.48, 3.21, and 2.50 cases, respectively. These rates were calculated using census data and population estimates published by the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) of Colombia.6

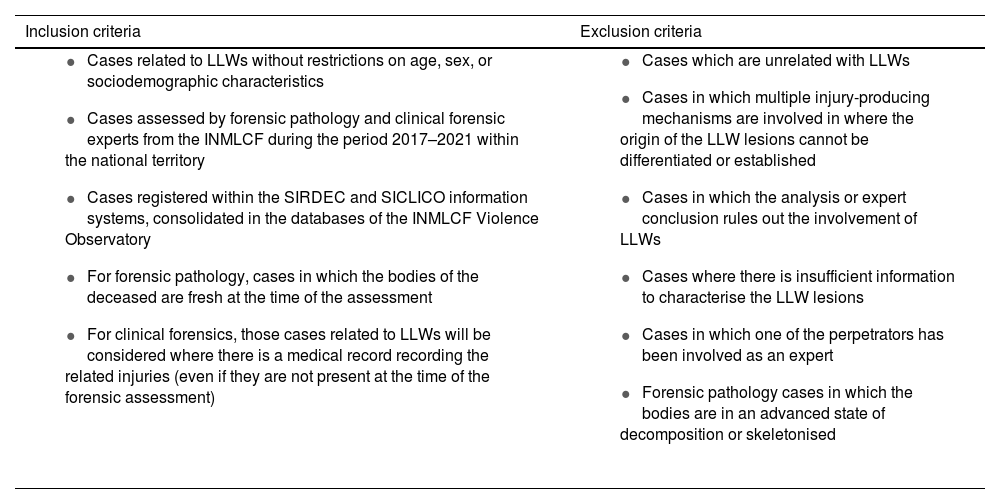

Most of the reported events centred on common crime (robbery, vehicle theft, extortion, micro-trafficking, among others) and fights (interpersonal violence and acts of intolerance). It is striking that 5% of the cases occurred in contexts of sociopolitical violence, which is related to the social unrest experienced in the country following the COVID-19 lockdown. The details of the circumstances of the events can be seen in Fig. 2.

Regarding the assailants reported by users during the assessments, the majority identified them as men (92%), and in 56.9% of cases, there was a single assailant, while in 40.6%, two or three assailants were involved. In 60.4% of cases, the assailant was identified by the victim as a police officer or member of the armed forces. In 24.1% of cases, the assailants were unknown to the victim or there was no information about them at the time of the assessment. Users' descriptions, assessed in relation to the context of the events and the type of primary aggressor reported, correlate with the attention given by police authorities as first responders to acts of violence (fights, common criminal acts), favouring the use of less force to control such situations. LLWs are some of the available tools for handling these situations.

Ninety-three percent of the injuries described for all LLW categories were mild in severity. Only 7% of the events were determined to be moderate in severity, and none of the cases analysed were determined to be severe.

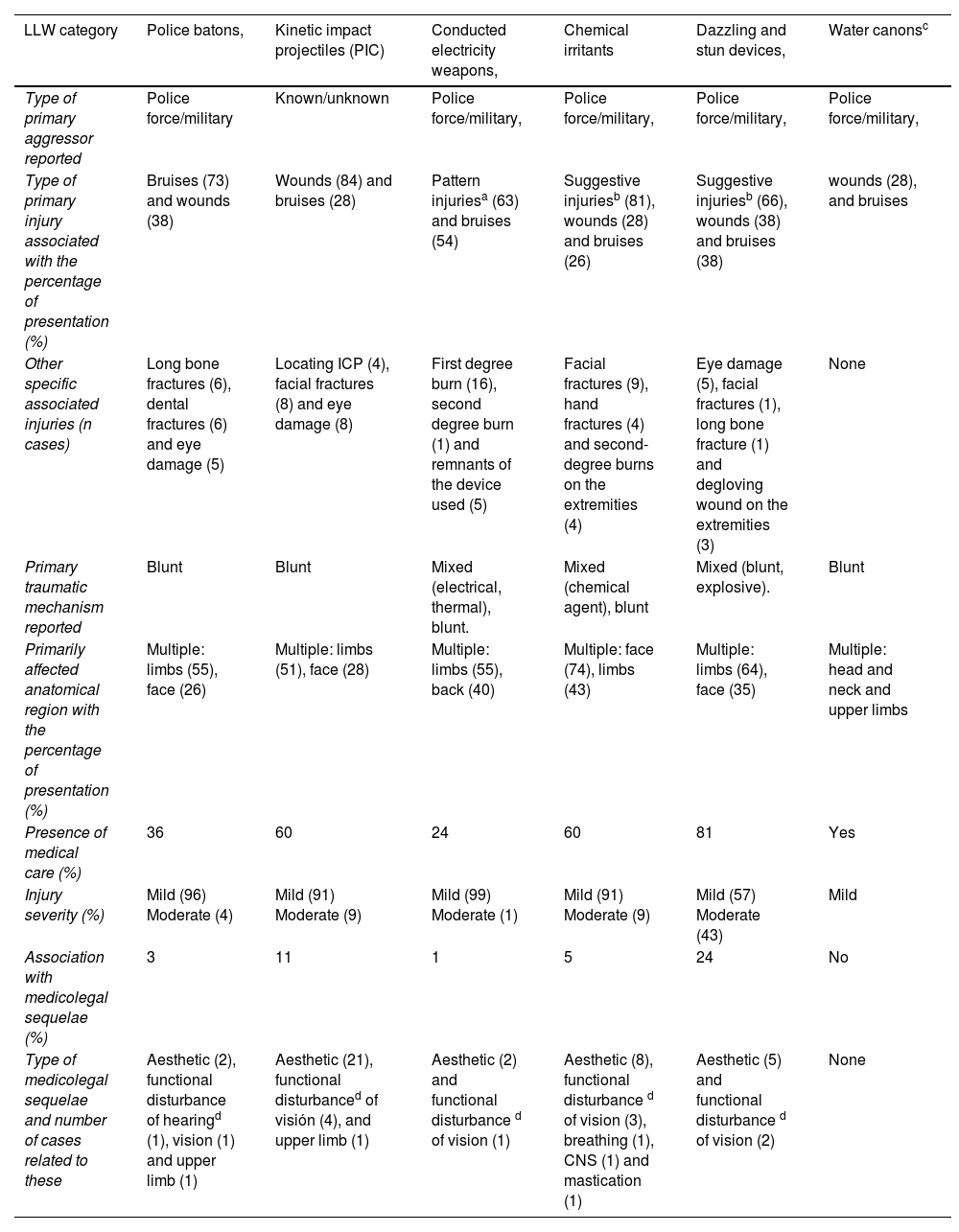

Table 4 shows the type of primary aggressor reported for the LLW categories, as well as the types and main characteristics of the injuries documented in each category.

Documented assailants and injuries by less-lethal weapon category.

| LLW category | Police batons, | Kinetic impact projectiles (PIC) | Conducted electricity weapons, | Chemical irritants | Dazzling and stun devices, | Water canonsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of primary aggressor reported | Police force/military | Known/unknown | Police force/military, | Police force/military, | Police force/military, | Police force/military, |

| Type of primary injury associated with the percentage of presentation (%) | Bruises (73) and wounds (38) | Wounds (84) and bruises (28) | Pattern injuriesa (63) and bruises (54) | Suggestive injuriesb (81), wounds (28) and bruises (26) | Suggestive injuriesb (66), wounds (38) and bruises (38) | wounds (28), and bruises |

| Other specific associated injuries (n cases) | Long bone fractures (6), dental fractures (6) and eye damage (5) | Locating ICP (4), facial fractures (8) and eye damage (8) | First degree burn (16), second degree burn (1) and remnants of the device used (5) | Facial fractures (9), hand fractures (4) and second-degree burns on the extremities (4) | Eye damage (5), facial fractures (1), long bone fracture (1) and degloving wound on the extremities (3) | None |

| Primary traumatic mechanism reported | Blunt | Blunt | Mixed (electrical, thermal), blunt. | Mixed (chemical agent), blunt | Mixed (blunt, explosive). | Blunt |

| Primarily affected anatomical region with the percentage of presentation (%) | Multiple: limbs (55), face (26) | Multiple: limbs (51), face (28) | Multiple: limbs (55), back (40) | Multiple: face (74), limbs (43) | Multiple: limbs (64), face (35) | Multiple: head and neck and upper limbs |

| Presence of medical care (%) | 36 | 60 | 24 | 60 | 81 | Yes |

| Injury severity (%) | Mild (96) Moderate (4) | Mild (91) Moderate (9) | Mild (99) Moderate (1) | Mild (91) Moderate (9) | Mild (57) Moderate (43) | Mild |

| Association with medicolegal sequelae (%) | 3 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 24 | No |

| Type of medicolegal sequelae and number of cases related to these | Aesthetic (2), functional disturbance of hearingd (1), vision (1) and upper limb (1) | Aesthetic (21), functional disturbanced of visión (4), and upper limb (1) | Aesthetic (2) and functional disturbance d of vision (1) | Aesthetic (8), functional disturbance d of vision (3), breathing (1), CNS (1) and mastication (1) | Aesthetic (5) and functional disturbance d of vision (2) | None |

Source: Prepared by the authors. LLWs: less-lethal weapon.

Pattern injury: Injuries described in the literature that enable correlation with a causal object. In the case of conductive electrical weapons, these were burns and small punctate abrasions.

Suggestive injury: Injuries that are not specific to the weapon trauma reported by the user, but can be correlated with an injury mechanism related to the use of a less-than-lethal weapon. Specifically, in the case of chemical irritants, the presence of irritation, congestion, or involvement of the conjunctiva, mucous membranes, or upper respiratory tract. In the case of dazzling and stun devices, first- and second-degree burns, as well as trauma from direct contact with the devices used.

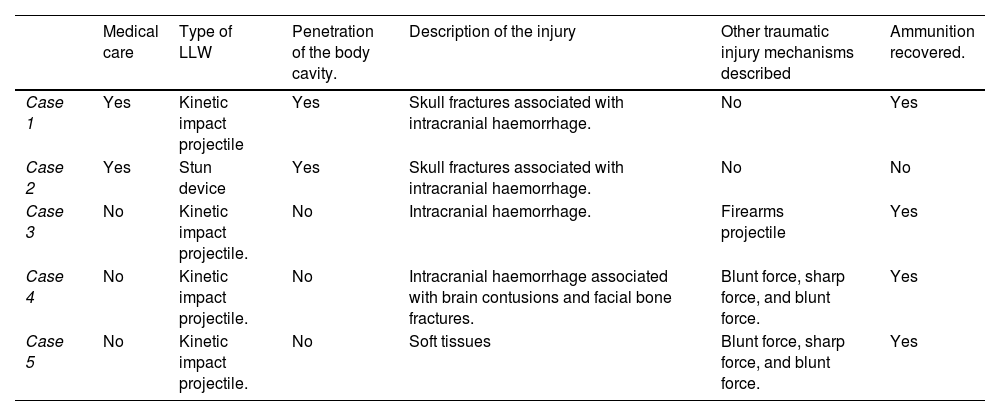

In the forensic pathology field, five cases involving deaths from LLWs were documented. All were men between the ages of 17 and 64. All presented head injuries; none of the cases showed macroscopic gunshot residue. Table 5 provides a summary of the variables associated with each case.

Characterisation of fatality cases in which injuries from less-than-lethal weapons were documented.

| Medical care | Type of LLW | Penetration of the body cavity. | Description of the injury | Other traumatic injury mechanisms described | Ammunition recovered. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Yes | Kinetic impact projectile | Yes | Skull fractures associated with intracranial haemorrhage. | No | Yes |

| Case 2 | Yes | Stun device | Yes | Skull fractures associated with intracranial haemorrhage. | No | No |

| Case 3 | No | Kinetic impact projectile. | No | Intracranial haemorrhage. | Firearms projectile | Yes |

| Case 4 | No | Kinetic impact projectile. | No | Intracranial haemorrhage associated with brain contusions and facial bone fractures. | Blunt force, sharp force, and blunt force. | Yes |

| Case 5 | No | Kinetic impact projectile. | No | Soft tissues | Blunt force, sharp force, and blunt force. | Yes |

Source: Prepared by the authors. LLW: less-than-lethal weapon.

It should be noted that one of the fatal cases involved a man who presented concomitant injuries from a conventional firearm projectile and injuries from a kinetic impact projectile. It was possible to differentiate the typical injuries caused by conventional projectiles (entry and exit wounds with internal and external cratering of the skull bones, respectively). However, these characteristics were not observed in the kinetic impact projectiles. Injuries caused by blunt force were documented, and the kinetic impact projectiles were recovered during the incident.

Some variables, such as the location and date of the events, as well as the alleged assailant, among others, are omitted from the results presented here because it is considered that these data may violate the confidentiality of the cases. Furthermore, the variable of information on the context of the events is limited to what the judicial authority was able to obtain at the time of the technical inspection of the corpse, which in all cases was partial due to difficulties in initially obtaining information about the events, due to the transfer of the bodies or specific social conditions that prevented it, such as the presence of mobs, crowds of people, among others.

DiscussionAs Haar et al. 7 propose, LLWs intrinsically have the capacity to cause harm and affect human health; for example, in the case of injuries resulting from kinetic impact projectiles, these are significantly severe and are associated with permanent disabilities or mortality.

This study showed that the most common LLWs in forensic clinical assessments correspond to police batons. However, in postmortem analyses, the use of kinetic impact projectiles stands out. In the case of non-lethal injuries, the characteristics of the injuries were established according to the type of LLW, and most of them were consistent with what was proposed in the literature regarding the general characteristics of the affected population, the range of presentation of the injuries produced, and their potential sequelae.

The injuries identified for kinetic impact projectiles, in the case of forensic pathology, involve head injuries, in which wounds with characteristics similar to those of a conventional firearm projectile entry wound were documented, although larger. Furthermore, in 4 of the 5 cases, the brain mass was compromised, which is directly related to the cause of death. This is consistent with what was reported by Haar et al.7 who documented that kinetic impact projectile injuries to the head can be significantly severe and are associated with permanent disabilities or mortality. Additionally, three of the four fatal cases in which kinetic impact projectiles were used presented injuries such as skull fractures and cranial haemorrhage, which was discussed by Ortega in his systematic review of LLW injuries to the facial area,8 as well as by Silva in his review of autopsies involving injuries from non-lethal kinetic energy weapons.9

Regarding the other LLW categories, forensic clinical trials found injuries with specific characteristics for each, but a lack of systematic reviews in the scientific literature prevents a generalised discussion of the results beyond case reports. Ecchymosis was the lesion present in all categories, being the most frequent in cases associated with police batons and occurring in more than half of the cases involving conductive electrical weapons. For their part, the injuries were found in expected cases, such as kinetic impact projectiles, and with a higher frequency than expected from police batons, stun guns, and chemical irritants.

Regarding the severity of the injuries, there is a notable discrepancy with that proposed by Haar et al.7 because the classification proposed by them does not specifically distinguish the medical management requirements for LLW injuries. This discrepancy is evident in the results of their systematic review, where 70% of the injuries were considered severe. This contrasts with the results of the present investigation, where none of the cases presented injuries of such severity according to the proposed classification. Only 7% of these were considered moderate in severity, with injuries including eyeball ruptures, long bone fractures, facial fractures, and burns.

Regarding the national sociodemographic context, a similarity was found with the annual reports generated by the INMLCF (National Institute of Statistics and Census), in Forensis: Data for Life,10 specifically regarding the variables of georeferencing, temporality, and context of the events. Regarding the latter, the events are mainly related to common crime events, brawls, and legal detentions (temporary or permanent deprivation of an individual's liberty by the competent authority); only 5% of the cases were related to sociopolitical violence (protests or social demonstrations).

The use of LLWs, mainly in fights and common crime scenarios, suggests that they are easily obtained by the civilian population. In Colombia, carrying LLWs is legal, provided a permit is obtained from the competent authority.11 Currently, there is no published data on the number of LLWs registered or the number of permits issued, which limits the analysis of injuries to civilians.

LimitationsFor the development of this study, limitations were found in the absence of specific descriptors for extracting cases of interest from information systems; the lack of standardised procedures focused on addressing and recording these types of cases; the diversity of styles in the writing of expert reports, which can lead to the loss of information regarding the characteristics of the events or underreporting of them in both forensic pathology and clinical practice; the difficulty for experts in relating their findings to the contextual information provided, and the nature of LLWs, and their multiple mechanisms of injury. Furthermore, there may be underreporting of data, since not all cases reach a forensic assessment.

RecommendationsGiven the constant increase in the number of cases found for this study, guidelines and protocols for the specific approach to injuries resulting from the use of LLWs must be created, developed and implemented. Furthermore, considering the context of each case and the possibility that these cases may be related to the use of LLWs by state forces, it is of utmost importance to properly document these injuries through appropriate and standardised protocols, such as the Minnesota Protocol for Forensic Pathology Cases.

Additionally, it is recommended that individuals who use LLWs must be trained, emphasising that the misuse of these types of weapons carries a high risk of serious consequences or even death, especially with weapons that use kinetic projectiles or stun devices.

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted by two principal investigators, with institutional support for data collection. Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the National University of Colombia, Bogotá campus, as well as authorisation and access to information from the INMLCF databases.

FundingThe authors declare that this research did not receive any specific funding from public, commercial, or non-profit agencies.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the conducting of this research.

Please cite this article as: Castrillón Parada JC, Jurado Portilla D, Cortés Castro CA, Pardo Sierra F. Forensic characterization of injuries caused by less-than-lethal weapons in Colombia (2017–2021). Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.remle.2025.500455.