Primary care (PC) and out-of-hospital emergency services (SUMMA112) are high-risk areas for malpractice claims due to their volume of activity and inherent uncertainty. Compensation claims that do not involve criminal liability require a preliminary administrative procedure. We analyzed the reasons and outcomes of these resolutions.

Materials and methodsThis is a cross-sectional observational study of advisory opinions issued by the Legal Advisory Commission of the Community of Madrid regarding compensation claims for out-of-hospital healthcare liability between 2013 and 2022. The variables analyzed included administrative, clinical, judicial, temporal, and compensatory factors.

ResultsA total of 616 rulings, 75 (12.2%) were related to out-of-hospital care: 43 (57.3%) in family medicine in PC and 28 (37.3%) in SUMMA112. Of these 42.7% were partially or fully upheld. The median compensation was €37,744 (range €600–€370,000). The 34 (45.3%) patients who died received more favorable outcomes (55.9% vs. 31.7%) with higher compensations (€47,900 vs. €22,900). The average delay between the claim and the opinion was 775 days. Reasons for claims included delayed or erroneous diagnosis in 42 cases (50,6%), treatment errors in 14 (16,9%), malpractice in 10 (12%), informed consent issues in 9 (10,8%) and adverse treatment effects in 7 (8,4%). The most frequent diseases were acute cardiovascular conditions (27%, including myocardial infarction and stroke), oncological diseases (16%), vaccine-related incidents (8%), and trauma (8%).

ConclusionsAcute cardiovascular and oncological pathologies generated the highest number of claims. Diagnostic delay or error was the primary reason cited, often linked to the loss of opportunity. Less than half of the claims were upheld, with compensation amounts significantly lower than those requested, and higher amounts awarded in cases involving patient death. Resolution times exceeded two years.

La atención primaria (AP) y urgencia extrahospitalaria (SUMMA112) son ámbitos de riesgo de reclamaciones por su volumen de actividad e incertidumbre. Las reclamaciones patrimoniales sin exigencia de responsabilidad penal requieren un procedimiento administrativo prejudicial. Analizamos los motivos y sentido de estas resoluciones.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional transversal de dictámenes de la Comisión Jurídica Asesora de la Comunidad de Madrid sobre reclamaciones de responsabilidad patrimonial en atención sanitaria extrahospitalaria entre 2013 y 2022. Las variables analizadas fueron administrativas, clínicas, judiciales, temporales e indemnizatorias.

ResultadosDe 616 dictámenes, 75 (12,2%) correspondían a asistencia extrahospitalaria: 43 (57,3%) medicina de familia de AP y 28 (37,3%) SUMMA112. El 42,7% se estimaron parcial o totalmente. La indemnización mediana fue de 37.744 € (intervalo 600–370.000 €). Los 34 (45,3%) pacientes que fallecieron obtuvieron más estimaciones (55,9% vs. 31,7%) y de mayor cuantía (47.900 € vs. 22.900 €). La demora media entre reclamación y dictamen fue de 775 días. Los motivos fueron: retraso o error diagnóstico 42 (50,6%), de tratamiento 14 (16,9%), mala práctica 10 (12%), defecto de consentimiento 9 (10,8%) y efectos colaterales de tratamientos 7 (8,4%). Las enfermedades fueron: cardiovascular aguda 27% (infarto, ictus), 16% oncológica, 8% vacunas y 8% traumatismos.

ConclusionesLas enfermedades cardiovasculares agudas y oncológicas generan más reclamaciones. El error o retraso diagnóstico fue el principal motivo alegado por suponer una pérdida de oportunidad. Se estiman menos de la mitad de las reclamaciones, con indemnizaciones sensiblemente inferiores a las solicitadas, mayores cuando el paciente falleció. La demora de la resolución supera los 2 años.

In the Community of Madrid (CM), 55 million primary care (PC)1 consultations are carried out each year by family doctors, paediatricians, nurses, dentists, and physiotherapists, among others. The Emergency Coordination Service (SUMMA112), also in the out-of-hospital area of Madrid, channels urgent demand through home care or hospital transfer, providing 1.5 million consultations per year.1

Some of these interventions result in harm to patients, which is inherent to the uncertainty and inherent risk of healthcare interventions. When this harm is perceived as unjust by the injured parties and their families, due to inadequate care, lack of diligence, or failure to provide adequate resources, it gives rise to the right to claim compensation for damage caused by professional acts or omissions (medical negligence, incompetence, or recklessness). Compensation can be claimed through civil proceedings (private healthcare) or through the administration's assets (public sector). If the recklessness that caused the damage is such that the victim considers that the professional deserves to be personally punished, he/she can claim through criminal proceedings: a conviction would entail, in addition to imprisonment, a fine or professional disqualification and compensation for subsidiary civil liability. The procedure established for the financial liability of the administration requires that administrative channels be exhausted before going to court to seek compensation from the administration that caused the damage.2,3 This gives the health service the opportunity to acknowledge the damage caused and compensate the injured party without going to court, saving time and money for both parties. If the administration's response is unsatisfactory, the injured party retains the option of bringing a claim through the contentious-administrative courts. If the claim exceeds €15,000 or if no specific amount is indicated, a preliminary ruling by the Legal Advisory Commission (CJA) of the Community of Madrid is required4,5 (“Advisory Council” in other autonomous communities). Its rulings are published periodically in anonymised form.

The aim of this study was to analyse the rulings published by the CJA of the Community of Madrid (CM) on previous claims by users or their relatives for healthcare liability (RPS) for acts by out-of-hospital professionals in the Spanish public health system (SPS). The arguments of the claim, its acceptance or rejection, would make it possible to identify areas for improvement in healthcare and potentially reduce litigation.

Material and methodsThis is an observational, cross-sectional, retrospective study analysing RPS rulings with compensation claims of more than €15,000 or an unspecified amount, published by the CJA of the CM on its website, with a decision date between January 2013 and December 2022, regardless of the date of the events or the date of the claim by the injured party. The cases analysed were those in which primary care or SUMMA112 was primarily involved in the act or omission giving rise to the claim. They contain the background to the event, arguments of the claimants, professionals, and medical inspection, where applicable, legal considerations, formal and substantive legal arguments, conclusions, and proposed resolution for the consulting body, usually the Regional Ministry of Health. Administrative variables (scope, professionals involved), clinical variables (diseases treated, preventive or curative activity, survival) and legal variables (legal arguments used, delay in resolution, amount of compensation requested and resolution) were analysed.

With regard to ethical considerations, the rulings analysed are public and anonymous with regard to the actors involved, so there is no risk of breach of confidentiality in the processing of the data.

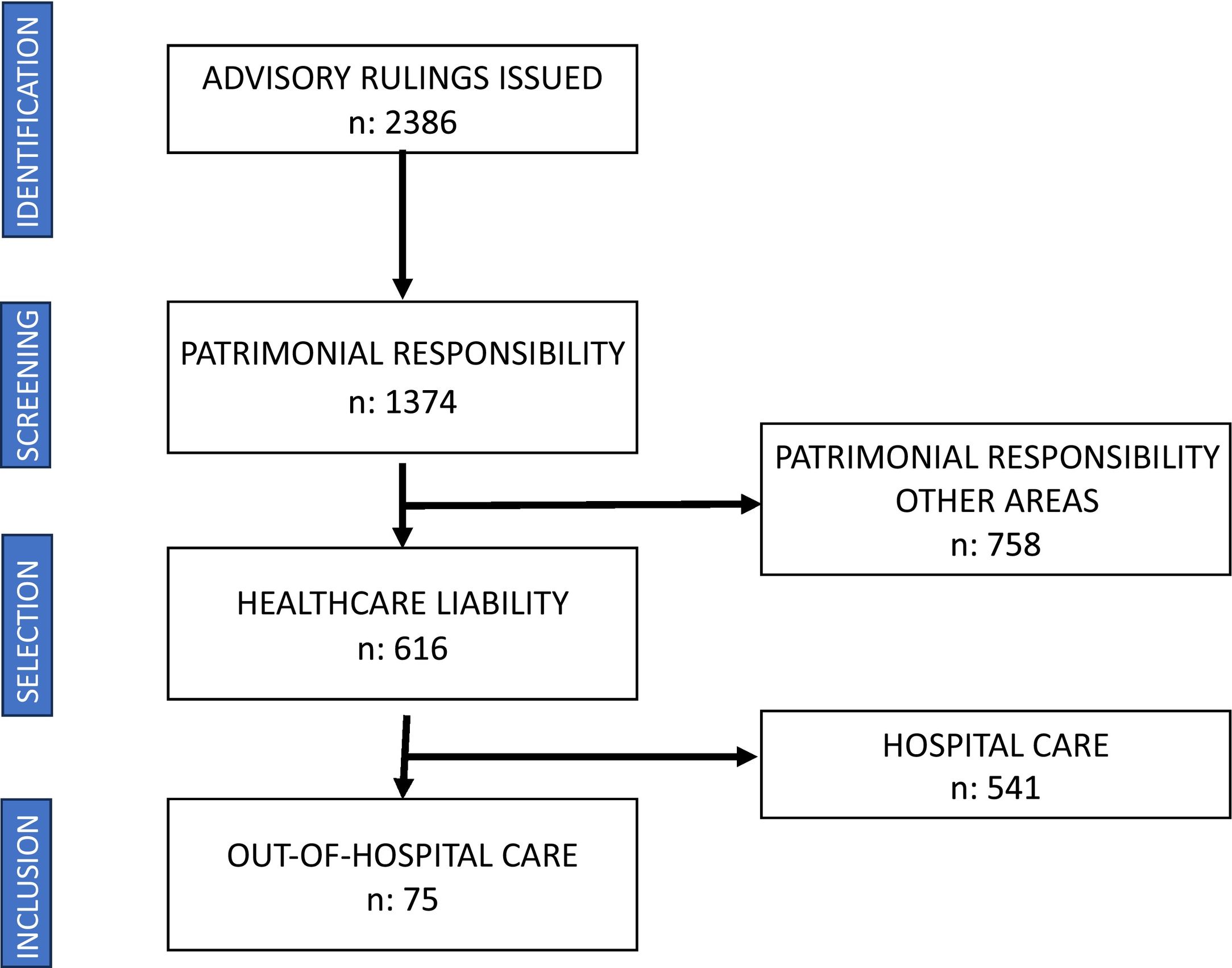

ResultsThe CJA database contains 2386 rulings issued between 2013 and 2022, of which 1374 deal with issues of financial liability. Of these, 616 (44.8%) rulings were analysed in relation to RPS, of which 75 (12.2%) were wholly or partly related to out-of-hospital actions. (Fig. 1) General practitioners (GPs) and adult primary care nurses were involved in 43 (57.3%) cases, out-of-hospital telephone services (SUMMA112) in 28 (37.3%), out-of-hospital paediatrics in 3 (4.0%), and the palliative care home support team (ESAD) in one (1.3%). (Fig. 2).

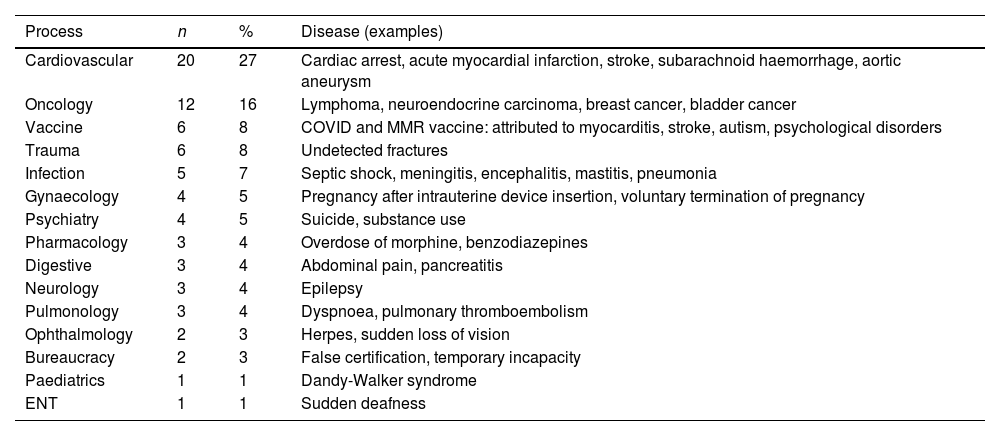

In terms of the diseases for which the claims were made (Table 1), there were 20 cases of acute cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, stroke, myocarditis), 12 cases of cancer, 6 cases related to vaccine administration, and 6 cases of trauma. In 34 (45.3%) cases, the family reported that the patient had died as a result of the healthcare provided.

Diseases for which claims were made (does not imply that the claim was resolved).

| Process | n | % | Disease (examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | 20 | 27 | Cardiac arrest, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, subarachnoid haemorrhage, aortic aneurysm |

| Oncology | 12 | 16 | Lymphoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, breast cancer, bladder cancer |

| Vaccine | 6 | 8 | COVID and MMR vaccine: attributed to myocarditis, stroke, autism, psychological disorders |

| Trauma | 6 | 8 | Undetected fractures |

| Infection | 5 | 7 | Septic shock, meningitis, encephalitis, mastitis, pneumonia |

| Gynaecology | 4 | 5 | Pregnancy after intrauterine device insertion, voluntary termination of pregnancy |

| Psychiatry | 4 | 5 | Suicide, substance use |

| Pharmacology | 3 | 4 | Overdose of morphine, benzodiazepines |

| Digestive | 3 | 4 | Abdominal pain, pancreatitis |

| Neurology | 3 | 4 | Epilepsy |

| Pulmonology | 3 | 4 | Dyspnoea, pulmonary thromboembolism |

| Ophthalmology | 2 | 3 | Herpes, sudden loss of vision |

| Bureaucracy | 2 | 3 | False certification, temporary incapacity |

| Paediatrics | 1 | 1 | Dandy-Walker syndrome |

| ENT | 1 | 1 | Sudden deafness |

A total of 83 main arguments were identified from the claimants, in some cases several in the same claim:

- –

Initial delay or error in diagnosis resulting in a “lost opportunity” for treatment: 42 (50,6%).

- –

Delay in the application of treatment or care when a diagnosis already exists: 14 (16.9%).

- –

Malpractice or breach of lex artis: 10 (12%).

- –

Absence or defect in informed consent: 9 (10.8%).

- –

Adverse effects or ineffectiveness of treatments or vaccines: 7 (8.4%).

- –

Other: omission of a procedure in temporary incapacity, issuance of a fraudulent certificate, error in drug dosage, etc.

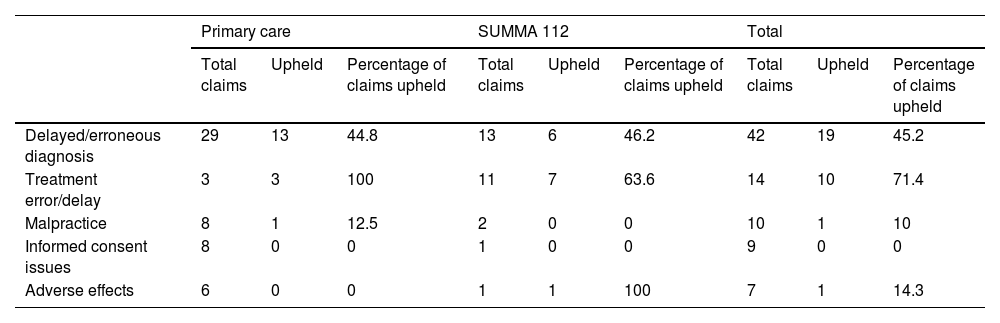

There were differences between the claims made against primary care and SUMMA112, attributable to differences in the circumstances of care (lex artis ad hoc) in each area of care. (Table 2).

Claims upheld according to healthcare setting and main reason for the claim (main results).

| Primary care | SUMMA 112 | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total claims | Upheld | Percentage of claims upheld | Total claims | Upheld | Percentage of claims upheld | Total claims | Upheld | Percentage of claims upheld | |

| Delayed/erroneous diagnosis | 29 | 13 | 44.8 | 13 | 6 | 46.2 | 42 | 19 | 45.2 |

| Treatment error/delay | 3 | 3 | 100 | 11 | 7 | 63.6 | 14 | 10 | 71.4 |

| Malpractice | 8 | 1 | 12.5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 10 |

| Informed consent issues | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Adverse effects | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100 | 7 | 1 | 14.3 |

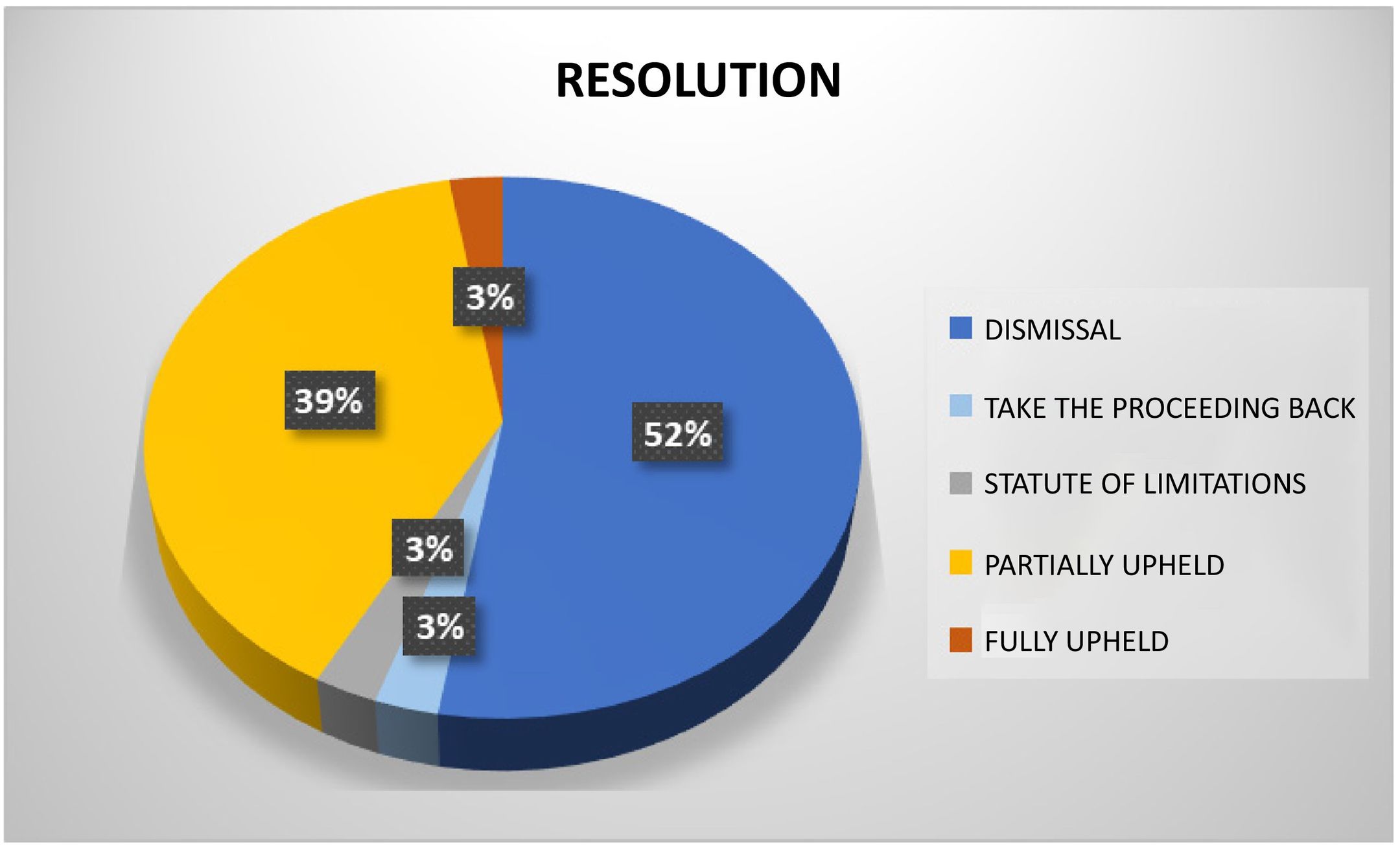

Resolution involved the dismissal of 39 of the 75 cases on the merits, two were time-barred due to the expiry of the time limit, and in two more, it was ordered to take the proceeding back to a prior stage (Fig. 3), a total of 43 (57.3%) were not upheld. The remaining 32 (42.7%) claims were upheld.

The amounts claimed ranged from €15,000 to €1.5 million, with a median of €219,000; in 28% of the cases, no specific amount was indicated in the claim. The median amount awarded was €37,744 (€600–€370,000). Only in two cases was the claim granted in full.

Compensation was more likely (55.9% vs. 31.7%) and higher (median €47,900 vs. €22,900) for the 34 deceased than for the survivors, odds ratio 2.7 (95% CI: 1.06–7.01).

The average delay between the claim and the final ruling was 1448 days. The average delay between the harmful event and the claim was 378 days (19 cases more than a year) and 775 days between the claim and the resolution. The longest delay between the event and resolution were for eight cases in which the administrative procedure was suspended due to parallel criminal proceedings.

DiscussionProfessional liability is the obligation to compensate for damage caused to the rights or interests of another person as a result of a negligent or culpable act or omission by a professional. Article 106.2 of the Spanish Constitution guarantees citizens the right to compensation for any damage caused to their property or rights as a result of the operation of public services, under the conditions established by law.2,3 The CM guarantees the exercise of this right for damages caused by the actions of the health service through the procedure for claims of patrimonial responsibility. If the amount claimed exceeds €15,000 or is unspecified, the CJA analyses each claim to ensure that the conditions for granting compensation are met.

Active legal standing is required; only the injured party may file a claim, except in cases of minority, incapacity, or death, in which case their representatives or relatives may do so. The resolutions analysed reject the claim if the representative is not duly accredited. Passive legal standing corresponds to the Madrid administration, as the healthcare act (or omission) was carried out in centres or healthcare units of the Madrid SPS. The administration itself is also responsible for the care provided in contracted services, regardless of the legal relationship. We have found judgements on events that occurred in private centres contracted by the SPS.

The statute of limitations sets a time limit. It is one year from the date of recovery, death, or determination of the extent of the sequelae. Two cases were dismissed due to the statute of limitations because the claims were filed more than one year after the death. There are situations that “interrupt” the statute of limitations, such as the filing of a criminal complaint, as occurred in eight cases that were prolonged. Even if the criminal proceedings are dismissed or result in an acquittal, the way is still open for RPS.

For there to be RPS, there must be evidence of malpractice, individually assessable financial damage or loss, and a causal link between the two. The CJA denied compensation in a case of morphine overdose in a terminal patient who later regained consciousness, as no actual damage could be proven. It also refused to award compensation when the progression of the underlying disease (cancer) itself caused the alleged damage or even death, which was not caused by the healthcare action. The possibility of moral distress in the absence of actual damage (material, financial, physical, or psychological),6 is recognised. In such cases, the CJA awards lower compensation (up to €8000) in cases of delayed diagnosis without demonstrable harm.

Loss of opportunity is the most frequently alleged ground by claimants, related to diagnostic and therapeutic delays. It is characterised by “uncertainty as to whether the omitted medical action could have prevented or reduced the patient's poor state of health”.7 This loss of opportunity arises both from diagnostic or therapeutic error and from diagnostic or therapeutic delay, which usually coincide successively in each case. The initial “error” delays the appropriate diagnosis or treatment. An incorrect initial diagnosis is made, with initial management that is also inadequate and harmful, which is subsequently corrected, with a “delay” (sometimes postmortem) allowing the initial error to be identified. Loss of opportunity is not as prominent in other RPS studies in fields such as cardiology, vascular surgery, or gynaecology,8 probably due to the lower burden of diagnostic uncertainty in specialised hospital care.

The breach of lex artis is justified not so much by the material damage, but rather by the uncertainty as to the sequence of events that would have occurred if the service had been provided differently. It is similar to moral distress as a compensable concept, calculated on the basis of the probability of avoiding the damage if the service had been provided with due care. For example, breast cancer that was not diagnosed after an initial mammogram, or ophthalmic herpes that was initially mistaken for conjunctivitis, both deserve compensation for the loss of opportunity caused by the delay.

For compensation to be awarded, there must be a causal link between the harm and the medical error (malpractice), which must be direct, immediate, and exclusive. The intervention of extraneous factors that may break the causal link, such as force majeure, the intervention of third parties, or the fault of the victim, suspends liability. This was the case with a patient who did not follow the doctor's advice to see a social worker to arrange a voluntary termination of pregnancy, thereby relieving the administration of any obligation to compensate her for the birth; or the delay of an ambulance during a snowstorm.

Damage for which the user is not legally liable is called unlawful damage, since not all damage caused by the administration has to be repaired. The existence of damage (objective liability) is not sufficient; it is necessary to refer to the criterion of lex artis ad hoc, or correct medical practice according to the circumstances. There are harms, including death, which are part of the uncertainty of care and are not attributable to medical action. The healthcare system has a “duty of means” but not a “duty of outcomes”. The outcome for the patient's health or life cannot be guaranteed, but it can be guaranteed that the care was provided correctly, in accordance with the state of knowledge and the means available. For this reason, compensation was denied to the family of a patient who died despite being resuscitated correctly; however, compensation was awarded after a contrast agent was administered to a person known to be allergic to it, causing their death.

The requirement for prior consent and information for all healthcare procedures is the main source of claims in hospital litigation in its written consent form;8,9 however, it is barely present in the study (12%), as in primary care most interventions only require verbal information and consent. Three claims for damages attributed to COVID vaccines (myocarditis, stroke, cognitive problems) are based on inadequate information, but the administration denies them on the grounds that written consent was not compulsory and was given verbally, especially since the vaccination was carried out according to the uniform criteria of the Interterritorial Council, with information provided to the population. Although the lack of information on certain side effects is acknowledged, the “state of science” at the time of vaccination is what supports the lack of responsibility of the administration (Article 34.1 of Law 40/2015)3 because they were unknown at the time.

There is prohibition of “retroactivity”, i.e. medical actions cannot be judged in the light of later results.10 In legal terms, judgements are not made ex post facto, but ex ante. For example, no compensation will be awarded for failure to diagnose pancreatitis when the general practitioner treated a patient with abdominal pain that had developed a few hours earlier and without any suggestive clinical signs. The inadequacy of diagnostic tests, diagnostic errors, or delays, or the inadequacy of treatment cannot be called into question by the subsequent progression of the patient's illness.

In the field of telephone care, there are significant conflicts regarding telephone calls to the SUMMA112 emergency service due to delays in emergency response caused by poor data transmission between the caller (patient or family member) and the service operator. The need assessed by the service technician or doctor after taking the history and the availability of resources justifies the use of the appropriate resource. From transcripts of some recorded telephone conversations, it appears that miscommunication and nerves underlie many claims.

One of the most striking problems is the delay in the processing of cases by the administration, justified by the complexity of the issues to be dealt with, the request for additional reports from the medical inspectorate and other bodies, the suspension due to ongoing criminal proceedings, or the initiation of negotiations between the parties with a view to conciliation.

The percentage of claims upheld (42.7%) is similar to other studies of financial liability in other fields, with lower amounts of compensation than in other specialties,8,9 and higher when the acknowledged error led to death. Studies in countries such as the United States report that only 22% of claims result in compensation.11 The only financial claim in primary care where the claimant was fully satisfied with the compensation was related to the issue of a certificate of sick absence (not temporary incapacity) which led to the dismissal of the worker on suspicion of forgery, as the GP initially denied issuing it.

One of the limitations of this study is that it analyses preliminary rulings involving amounts of more than €15,000 or an unspecified amount, where the administration against which the claim was brought is the deciding party. We do not have information on cases involving smaller amounts, cases that were settled by conciliation or legal claims.8 There is no analysis of the number of cases referred to the contentious-administrative court, but other studies show that litigation is low and that only a quarter of claimants have their claims upheld.9

The study covers 10 years and can therefore be considered representative, although the number of rulings is small due to the low level of litigation. In general, there are few financial claims in the CM for out-of-hospital care in relation to the volume of care, in line with studies of claims in primary care,12 and we observe a similar percentage of claims upheld as in hospital care and other specialties.13

Greater attention to consultations that lead to missed opportunities, such as diagnostic errors and delays in acute cardiovascular processes (heart attack, stroke, haemorrhage) and suspected cancer in the early stages of the disease, could reduce litigation at this level of care.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank Milagro Warleta Gil and Isabel del Cura González.

Please cite this article as: León Vázquez F, Nieto Sánchez Á, Santiago-Sáez A.S., Medical-legal analysis of claims for patrimonial liability in primary health care and extra-hospital emergency services in the Community of Madrid. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.remle.2025.500453.