In Mexico, Cryptococcus gattii sensu lato has been identified as the etiologic agent in approximately 10.8% of cryptococcosis cases; however, its isolation from natural sources, which would confirm its existence in the environment, has not been successful.

ObjectiveTo isolate C. gattii from environmental samples collected from trees within the movement area of a patient diagnosed with cryptococcosis caused by this species.

MethodsBased on a database of clinical isolates characterized as C. gattii, a patient was contacted and his route of movement was obtained; through a geospatial analysis, nearby trees were located. Tree hollows were sampled and the Cryptococcus isolates obtained were biochemically and genetically typed.

ResultsFour Cryptococcus isolates were obtained from the trees Schinus molle, Erythrina coralloides and from a specimen of the genus Pinus: three of them were characterized as Cryptococcus neoformans sensu stricto and one as C. gattii sensu stricto.

ConclusionsUsing a geographic information system led to delimit an environmental sampling area, resulting in the first documented report in Mexico of the isolation of C. gattii genotype VGI in nature.

En México, Cryptococcus gattii sensu lato ha sido identificado como agente etiológico en aproximadamente el 10,8% de los casos de criptococosis; sin embargo, su aislamiento a partir de fuentes naturales, que permitiría confirmar su permanencia en el ambiente, no ha sido exitoso.

ObjetivosAislar C. gattii a partir de muestras ambientales recogidas de árboles ubicados en el área de desplazamiento de un paciente diagnosticado con criptococosis causada por esta especie.

MétodosPartiendo de una base de datos de aislamientos clínicos caracterizados como C. gattii se estableció contacto con un paciente con el fin de conocer su área de movilidad; mediante un análisis geoespacial se ubicaron y muestrearon los árboles cercanos. Se tomaron muestras en oquedades de los árboles y los aislamientos obtenidos fueron tipificados bioquímica y genéticamente.

ResultadosA partir de ejemplares de árboles de las especies Schinus molle y Erythrina coralloides, y de un ejemplar del género Pinus, se obtuvieron cuatro aislamientos del género Cryptococcus, tres de los cuales fueron caracterizados como Cryptococcus neoformans sensu stricto y uno como C. gattiisensu stricto.

ConclusionesEl uso de un sistema de información geográfica permitió delimitar un área de muestreo ambiental y el aislamiento de la naturaleza de C. gattii genotipo VGI, hecho que constituye el primero documentado en México.

The presence of Cryptococcus gattii in environmental sources has been documented in several countries, with numerous records in North America, South America, Africa, and Australia.26 It is found in both tropical and temperate regions and has been isolated from a variety of plant species. For instance, it has been isolated from Eucalyptus camaldulensis in Australia,12Terminalia catappa in Colombia,17Moquilea tomentosa in Brazil,19 and Tamarindus indica, Pithecellobium dulce, Syzygium cumini, and Manilkara hexandra in India.28

In Latin America, C. gattii has been successfully recovered from detritus, plant material, tree cavities, decaying wood, and even wooden houses, including both native and introduced species. Host trees include native species such as Acacia visco, Cassia grandis, Hymenaea courbaril, Peltophorum dubium, Plathymenia reticulata, Tabebuia avellanedae and other species of the genus Tabebuia, Tipuana tipu and Roystonea regia; introduced species include Casuarina equisetifolia, Cedrus deodara, Corymbia ficifolia, species of the genus Croton, Cupressus sempervirens, Delonix regia, E. camaldulensis, Eucalyptus tereticornis and other species of the genus Eucalyptus, species of the genus Ficus, Grevillea robusta, species of the genus Phoenix, Senna siamea and Ulmus campestris, among others.7,13

The association of species from the Cryptococcus neoformans/C. gattii complex with trees has been linked to the degradation of lignin, a substrate of the enzyme laccase for synthesising melanin, a key pigment for the survival of the fungus,23,30 as well as to the stimulation of filamentation and reproduction of these species from plant detritus.16C. neoformans and C. gattii have been isolated from different parts of trees (bark, flowers, leaves, and soil debris). However, hollows provide optimal ecological conditions for yeast development and maintenance, as they can harbour hundreds of organisms that interact in key ecological processes, particularly wood decomposition. During this process, cellulose and lignin are transformed into carbon dioxide and water, releasing energy and generating a continuous source of nutrients available to the resident microorganisms.32

In Mexico, human cryptococcosis is primarily caused by the VNI genotype of C. neoformans and, less frequently, by species belonging to the C. gattii sensu lato complex.2,3,6,20 This infection has a low incidence compared to other conditions affecting the central nervous system. A study by Corzo-León et al. estimated the prevalence to be 8.2 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.11 However, sustained reporting of cases over time suggests that cryptococcosis represents a significant public health problem in Mexico, despite its low frequency, due to its high case-fatality rate.27

In terms of aetiology, most cases recorded between 1993 and 2015 were attributed to C. neoformans (84.8%), while 10.8% were associated with C. gattii and a small proportion remained unidentified.3,24 This reflects the pattern observed in other countries, where C. neoformans predominates, especially among immunocompromised individuals.14,27 Of the 10.8% of cases of C. gattii infection recorded, 50% were in immunocompetent individuals and 29.4% in immunocompromised individuals. This finding is consistent with the epidemiological profile of this species complex, which is characterised by its ability to infect hosts without apparent immunosuppression. At the molecular level, the most frequent genotype was VGII (53%), followed by VGI (26%), while VGIII and VGIV were detected in smaller proportions.4,6,15

The low frequency of C. gattii reported could be due to limited use of molecular diagnostic tools in clinical laboratories, an absence of systematic mycological surveillance programmes and limited diagnostic suspicion, particularly in patients without immunological risk factors. This underestimation could conceal a higher disease burden, particularly in regions where the ecological conditions are conducive to the presence of this species complex in the environment.

The only recorded instance of the environmental presence of C. gattii species in the country was the isolation of eight strains from 135 trees of the genus Eucalyptus in Mexico City.1 Unfortunately, the isolates were not preserved, preventing further genotyping studies. Additionally, the precise location of the trees was not recorded, hindering the ability to replicate the sampling process and obtain new isolates. Since then, locating this yeast in the urban environment of Mexico City has proven challenging, with no conclusive results.5,8

For this reason, this research project conducted a geospatial study in which the main location variables were the residences of patients diagnosed with meningeal cryptococcosis caused by C. gattii sensu lato, as well as their routes of movement. The sampled trees were those with cavities.

1Materials and methods1.1PatientsCases of cryptococcosis caused by C. gattii were evaluated for inclusion in this study at the Manuel Velasco Suárez National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery (INNN) between 2010 and 2015. The following criteria were considered: the availability of the strain; the patients’ place of residence; and their willingness to participate in the study, in order to gather information about their area of movement. Determining the area of mobility was necessary in order to establish the area of exposure to the fungus and define the environmental sampling zone.

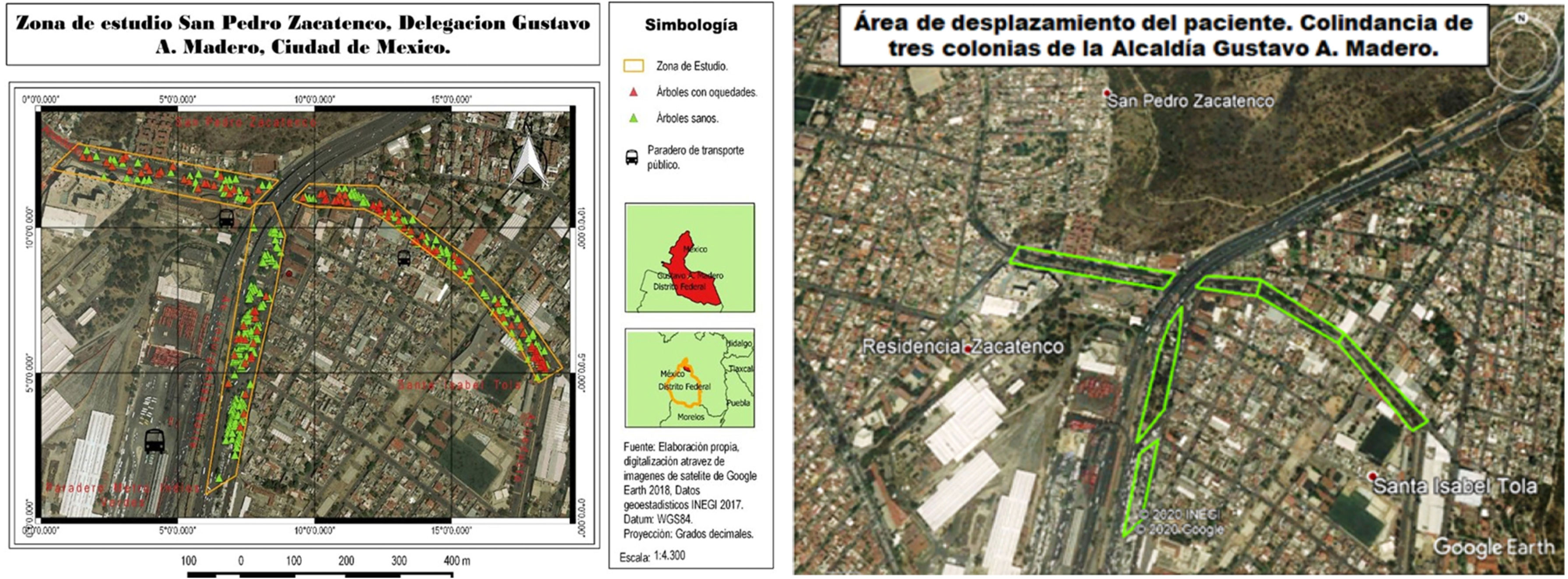

1.2Tree recording and sample sizeVisits were made to the areas referred to by the finally selected patients, and the streets with the highest number of trees were chosen (Google Earth https://www.google.es/intl/es/earth/index.html). A census of the trees was conducted, with information collected on species name, number of specimens and geographical coordinates (Garmin eTrex 20x GPS). Using QGIS 3.4 software, the georeferenced points were included, and a map of the area was created in three quadrants (Fig. 1). The sample size was calculated, and cluster sampling was performed using the absolute difference criterion for binomial distribution with a known population.21 Trees were selected based on the inclusion criteria of having hollows and a trunk diameter greater than 30cm.

1.3Reference strainsThe following reference strains were used: C. neoformans WM148 (VNI/AFLP1), WM626 (VNII/AFLP1A), WM628 (VNIII/AFLP2), WM629 (VNIV/AFLP3) and WM179 (VGI/AFLP4); and C. gattii WM178 (VGII/AFLP6), WM175 (VGIII/AFLP5) and WM779 (VGIV/AFLP7). Dr W. Meyer kindly provided these.25

1.4Isolates from the studyThe INNN was asked to reseed the C. gattii isolate with the code FM277 of one of the patients. Environmental samples were obtained by inserting a sterile cytological brush into the hollows in the trunks and extracting a fragment of the substrate using rotary movements. This was then placed in glass tubes containing 5mL of 0.9% NaCl with antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin at 40μg/mL and chloramphenicol at 50μg/mL).7,9 In trees with multiple cavities, the sample was taken from the largest cavity. The sample was labelled with the geo-reference, the tree species, and the characteristics of the hollow (e.g. level of sun exposure, height, shape, and depth), then transferred to the laboratory. From the tube containing the original suspension, a volume of 100μL was extracted and 1:10, 1:100 and 1:1000 dilutions were made in duplicate in 0.9% NaCl. Twenty microlitres of each dilution were taken and inoculated by mass streaking onto Niger agar.33 The culture plates were incubated at 26°C for one week and checked daily for the growth of brown-pigmented yeast-like colonies. To reduce bacterial and fungal contamination, the isolates were reseeded on Niger agar and incubated at 26°C until a pure culture was obtained. These cultures were then stored on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA).

1.5PhenotypingThe reference strains, environmental isolates, and patient isolates were analysed based on their morphology (presence or absence of a capsule), physiology (growth at 37°C in SDA) and biochemical patterns (presence of ureases and phenoloxidases, resistance to l-canavanine, and assimilation of glycine in canavanine-glycine-bromothymol blue (CGB) agar.18,33

1.6GenotypingAll isolates were seeded in SDA and incubated at 26°C for 48h. DNA was then extracted from the isolates using the DNeasy®Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR-RFLP technique was then used to amplify the URA5 region with the URA5 (5′ ATGTCCTCCCAAGCCCTCGACTCCG 3′) and SJ01 (5′ TTAAGACCTCTGAACACCGTACTC 3′) primers to identify the genotypes. This yielded a fragment of approximately 779 bp, which was digested with the enzymes Sau961 and Hhal. The resulting restriction patterns were compared with those of the reference strains using 2.5% agarose electrophoresis.25

2Results2.1PatientsC. gattii was confirmed as the aetiological agent in six (20%) out of the 30 patients diagnosed with cryptococcosis at the INNN between 2010 and 2015; the corresponding strains were available for analysis. Of these six patients, only one, who resided in Mexico City, agreed to participate in the study.

2.2Area of movementDuring the interview, the patient reported working as a driver on routes corresponding to the areas marked on the map (Fig. 1). Consequently, the sampling area was delimited between parallels 19°29′36″ and 19°31′34″ N and meridians 99°06′54″ and 99°09′04″ W at an altitude of 2248m above sea level. The environmental conditions at the time of sampling were representative of the winter period in the region, with an average temperature of 14.4°C, relative humidity of 60%, moderate solar radiation and no precipitation during the three days prior to sampling.34

2.3Tree recording and sample sizeSampling was conducted between September 2018 and February 2019. A total of 400 trees were counted in the selected area, of which 99 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 46 were sampled after the sample size was calculated.

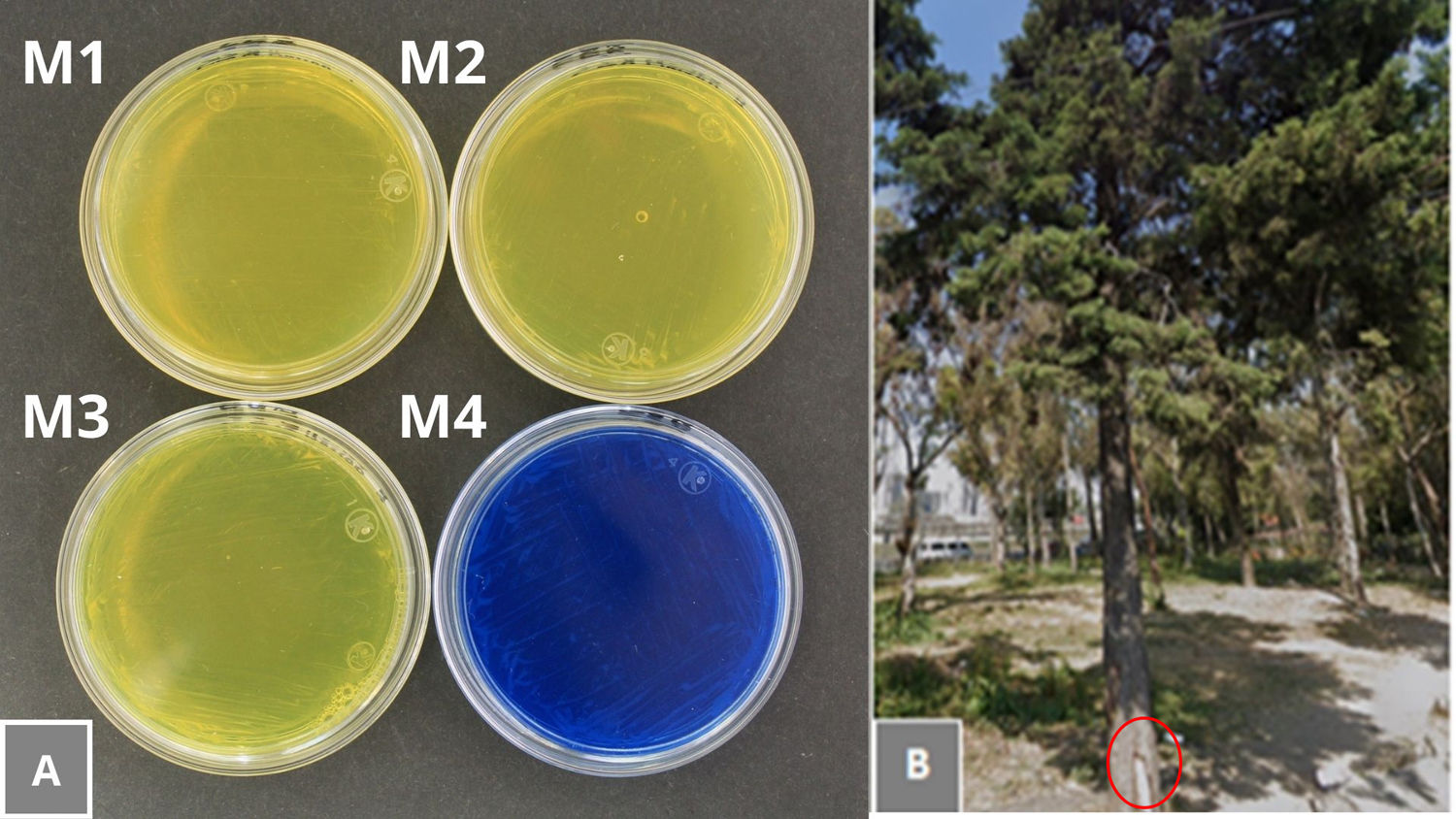

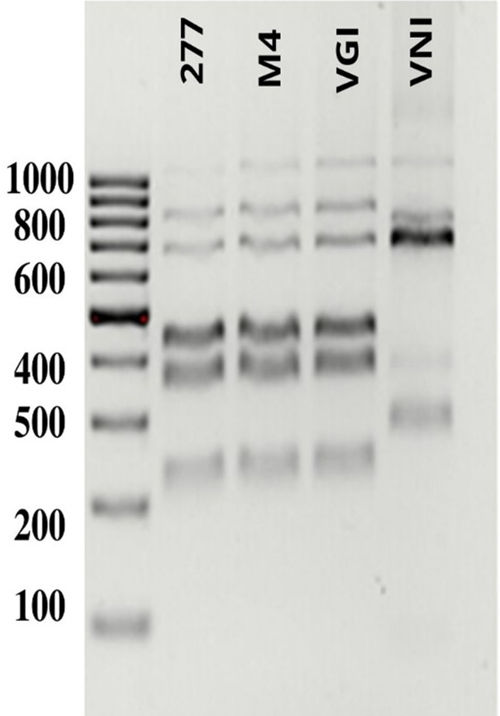

2.4Isolates obtained from sample cultureFour isolates (M1, M2, M3, and M4) with a dark brown pigment were obtained and recovered from Schinus molle (M1 and M2), Erythrina coralloides (M3), and a specimen from the genus Pinus (M4) (Table 1).

Geographic coordinates of trees and characteristics of hollows from which strains of C. neoformans and C. gatii were recovered in the Gustavo A. Madero district, Mexico City.

| Isolate | Identification in CGB medium | Origin of isolate (tree species and geographical coordinates) | Characteristics of hollows | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size(diameter) | Depth | Position relative to the tree | Sun exposure | |||

| M1 | C. neoformans s.l. | Schinus molleN 19°30.108′W 0.99°07.103′ | 10–15cm | From 5 to 10cm | Near the base | Medium |

| M2 | C. neoformans s.l. | Schinus molleN 19°30.108′W 0.99°07.103′ | 10–15cm | From 5 to 10cm | Near the base | Medium |

| M3 | C. neoformans s.l. | Erythrina coralloidesN 19°30.055′W 0.99°06.903′ | 5–10cm | Less than 5cm | Halfway up the trunk | Medium |

| M4 | C. gattii s.l. | Pinus sp.N 19°29.936′W 0.99°07.084′ | Less than 5cm | Less than 5cm | Near the base | High |

CGB: canavanine-glycine-bromothymol blue; s.l.: sensu lato.

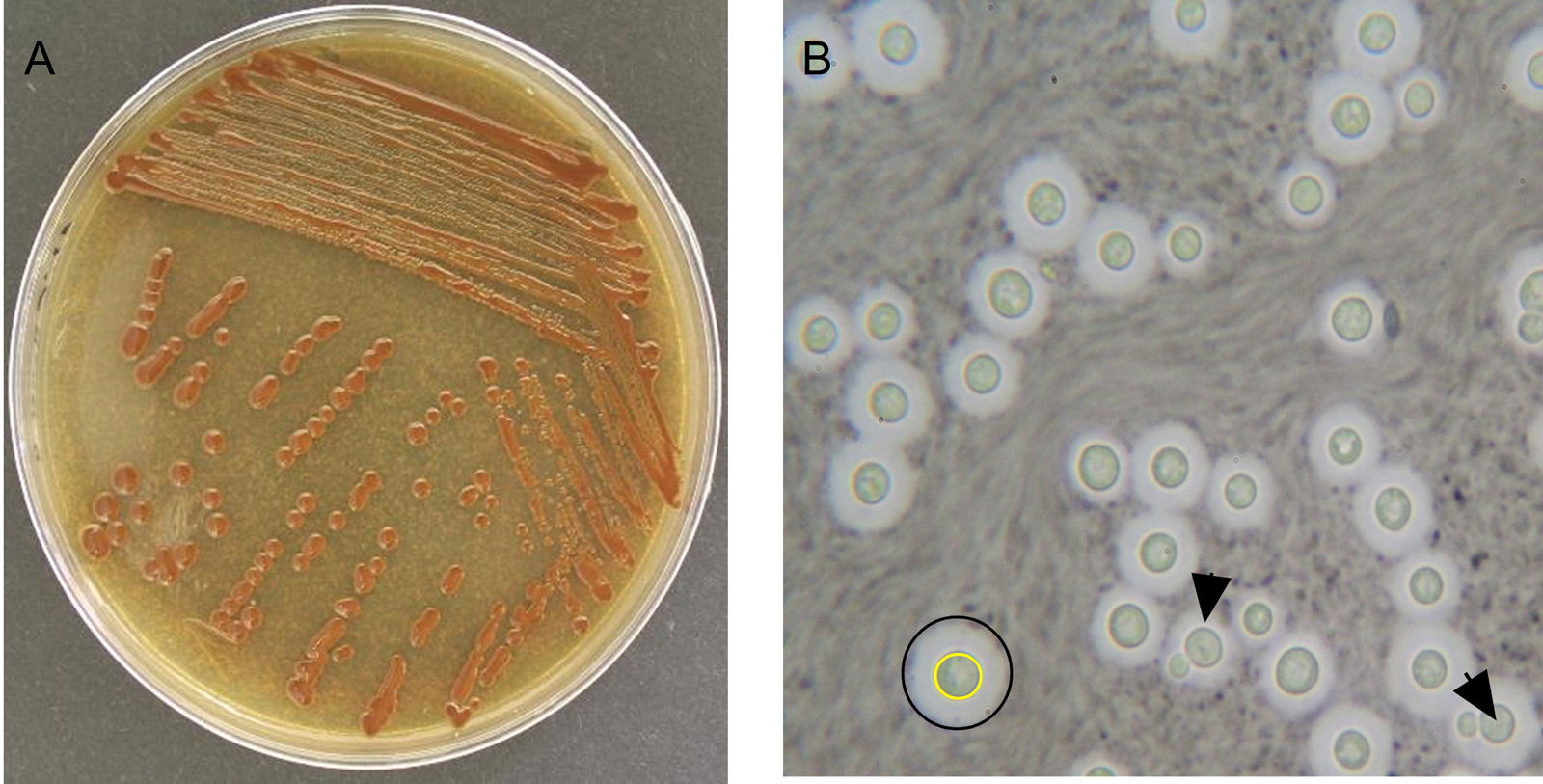

Microscopic examination with India ink showed that the reference strains, isolates M1 to M4 and the isolate from patient FM277 had capsules (Fig. 2). All isolates grew at 37°C and were positive for the urease and phenol oxidase tests, therefore were identified as belonging to the genus Cryptococcus. Isolates M1, M2, and M3 were negative for the CGB assimilation test (Fig. 3), suggesting the species C. neoformans sensu lato. In contrast, the clinical isolate FM277 and the isolate M4 were positive for this test and were identified as C. gattii sensu lato.

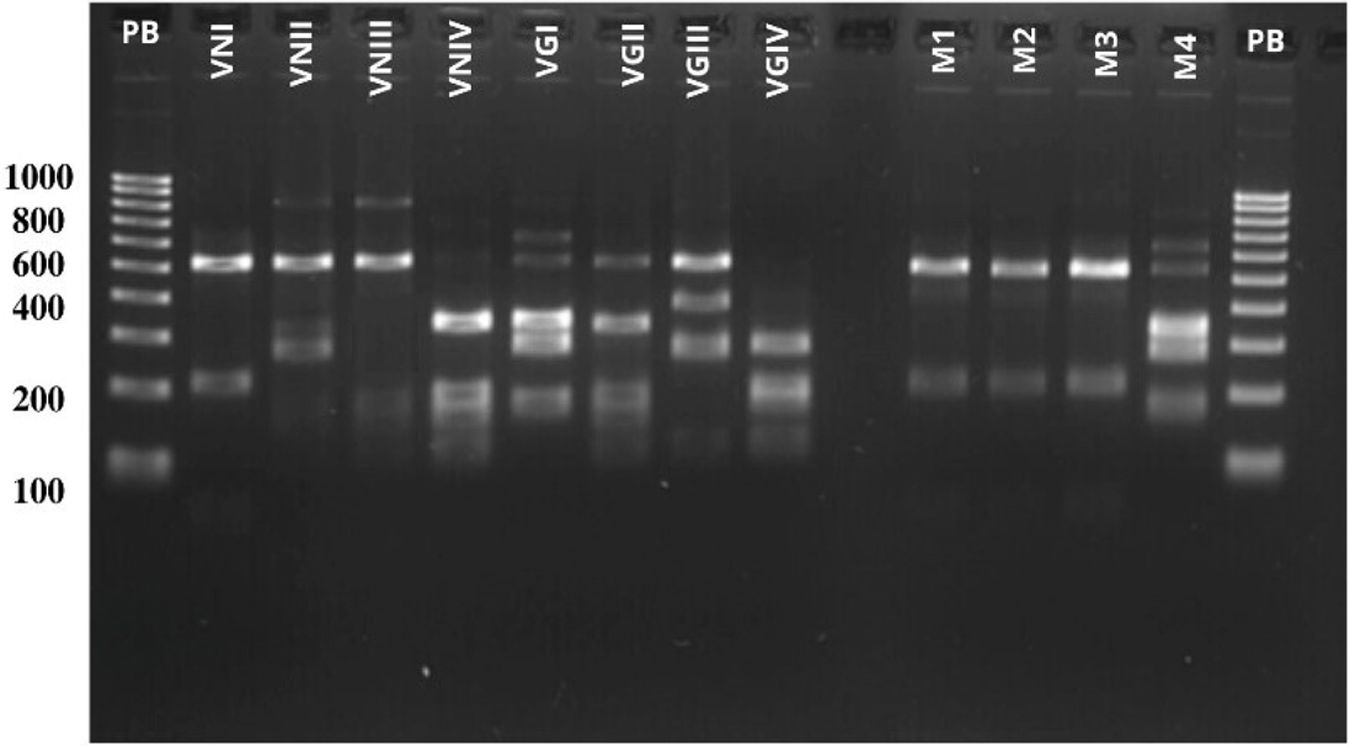

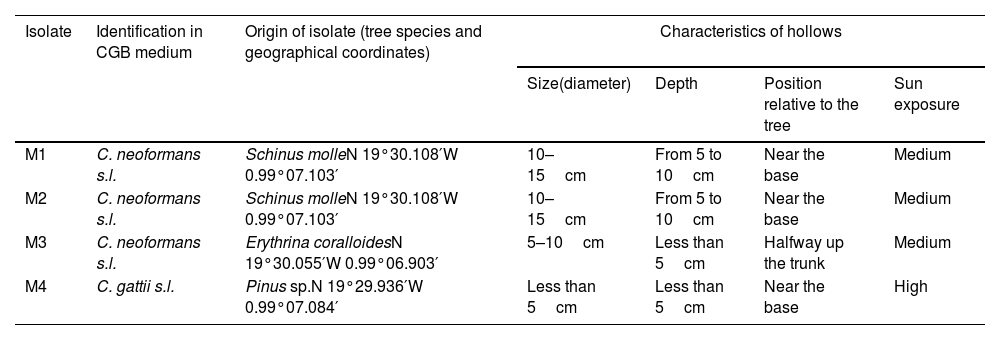

PCR-RFLP analysis of the URA5 gene identified isolates M1, M2, and M3 as belonging to the VNI genotype of C. neoformans (Fig. 4), while isolates FM277 and M4 were identified as belonging to the VGI genotype of C. gattii (Fig. 5).

PCR-RFLP patterns of the URA5 gene. Lanes 1 and 15 show the molecular weight marker (100 bp). Lanes 2–9 correspond to the eight reference strains VNI–VGIV.25 Lanes 11–13 correspond to the environmental isolates of C. neoformans (M1–M3), while lane 14 corresponds to the isolate of C. gattii (M4), all of which were recovered from tree hollows during this study.

PCR-RFLP patterns of the URA5 gene. Lane 1: molecular weight marker (100 bp). The following lanes show the patterns of the clinical isolate from the patient (277), the environmental isolate obtained from the specimen of the genus Pinus (M4), and the reference strains corresponding to the VGI and VNI genotypes.25

The isolation of C. gattii genotype VGI from a tree of the genus Pinus in Mexico City provides new evidence on the ecology of this yeast in the country's urban environments and expands our knowledge of its natural reservoirs, which has significant implications for medical mycology and public health. Reports of human cryptococcosis caused by C. gattii in Mexico account for approximately 10.8% of clinical isolates, suggesting that it is relatively prevalent in the country. However, identifying its environmental reservoir has proven unsuccessful or incomplete. This study documents the successful isolation of C. gattii VGI in the Mexican environment for the first time, thus contributing to our understanding of its local ecology.

The methodology employed, which incorporated data on patient movement and used geographic information systems (GIS) to define sampling areas, enabled the search to be focused on specific urban areas. As a result of this targeted sampling, four yeast-like isolates (M1, M2, M3, and M4) were recovered, representing an isolation rate of 8.7%.

The isolation of C. gattii from a Pinus specimen is consistent with reports by Cogliati et al. (2016) in the Mediterranean basin,10 and with the isolation of C. gattii from other gymnosperms, such as Cupressus, in studies conducted in Argentina29 and Colombia.31 Given the high diversity of Pinus species in Mexico, this finding suggests that these trees may act as natural reservoirs in the urban ecosystem, highlighting the need for further research to confirm this. From an epidemiological perspective, the fact that the clinical (FM277) and environmental (M4) isolates belong to the same genotype (VGI) suggests a potential link between environmental exposure and human infection. However, without high-resolution genomic studies, it is impossible to confirm whether both isolates share a clonal identity. This coincidence should be interpreted with caution, but it highlights the need for more detailed genetic analysis to clarify the possible connection between clinical and environmental isolates. The climatic conditions under which the sampling was carried out – an average temperature of 14.4°C, relative humidity of 60%, and no rainfall – are similar to those described in studies in which the percentage of C. gattii isolation ranges from 9.5% to 16.1%.28 The successful recovery of isolates demonstrates that C. gattii can persist in adverse environmental conditions, posing a potential exposure risk for urban populations even during the winter months.

From a public health perspective, it is particularly important to identify the environmental reservoirs of C. gattii. Cryptococcal infection caused by C. gattii can affect immunocompetent individuals, and clinical management is often prolonged and complicated. Furthermore, the inclusion of C. gattii in the World Health Organization's list of priority pathogens underscores the necessity of strengthening environmental and epidemiological surveillance strategies.35

Similarly, the presence of bacteria associated with tree cavities, such as Bacillus safensis and Acinetobacter baumannii, which have been identified in pine trees, could facilitate the survival and virulence of Cryptococcus species by inducing factors such as the formation of large capsules, melanin production, and the generation of titanic cells. This could have implications for the pathogenicity of environmental isolates.22 The low isolation rate obtained in this study (8.7%) is consistent with other international studies, suggesting that although C. gattii can be found in urban environments, targeted and specific sampling strategies are required for its detection. Using GIS to plan the sampling proved to be an effective tool and should be routinely incorporated into future environmental surveillance studies of fungal pathogens.

Overall, the results presented here reinforce the need for systematic environmental monitoring programmes that consider different tree species, seasonal variations, and climatic conditions, in order to adequately characterise the factors influencing the persistence and dispersal of C. gattii in urban environments in Mexico.

4ConclusionsThis paper describes the recovery of the first environmental isolate of the VGI genotype of C. gattii in Mexico. While the environmental isolate matches the clinical isolate found in our patient, it is not possible to determine their relationship without further genomic research.

Identifying the genus Pinus as a potential natural host of C. gattii underscores the importance of expanding environmental and epidemiological surveillance in urban areas. Geographic information systems (GIS) proved to be an effective tool for optimising the search for fungal reservoirs, and their systematic application is recommended in future research.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.