Candida bloodstream infection (CBSI) is a growing problem among patients with cancer.

AimTo describe the main clinical and microbiological characteristics in patients with cancer who suffer CBSI.

MethodsWe reviewed the clinical and microbiological characteristics of all patients with CBSI diagnosed between January 2010 and December 2020, at a tertiary-care oncological hospital. Analysis was done according to the Candida species found. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the risk factors associated with 30-day mortality.

ResultsThere were 147 CBSIs diagnosed, 78 (53%) in patients with hematologic malignancies. The main Candida species identified were Candida albicans (n=54), Candida glabrata (n=40) and Candida tropicalis (n=29). C. tropicalis had been mainly isolated from patients with hematologic malignancies (79.3%) who had received chemotherapy recently (82.8%), and in patients with severe neutropenia (79.3%). Seventy-five (51%) patients died within the first 30 days, and the multivariate analysis showed the following risk factors: severe neutropenia, a Karnofsky Performance Scale score under 70, septic shock, and not receiving appropriate antifungal treatment.

ConclusionsPatients with cancer who develop CBSI had a high mortality related with factors associated with their malignancy. Starting an empirical antifungal therapy the soonest is essential to increase the survival in these patients.

Los episodios de candidemia son un problema creciente en los pacientes con cáncer.

ObjetivosDescribir las principales características, clínicas y microbiológicas, en pacientes con cáncer que padecen candidemia.

MétodosSe revisaron todos los episodios de candidemia diagnosticados entre enero de 2010 y diciembre de 2020 en un hospital oncológico. El análisis se realizó comparando las principales especies de Candida identificadas. Se realizó análisis de regresión logística para identificar los factores de riesgo relacionados con la mortalidad a los 30 días.

ResultadosSe identificaron 147 episodios de candidemia, 78 (53%) en pacientes con neoplasias hematológicas. Las principales especies de Candida identificadas fueron Candida albicans (n=54), Candida glabrata (n=40) y Candida tropicalis (n=29). C. tropicalis fue aislada principalmente de pacientes con neoplasias hematológicas (79,3%), en aquellos que habían recibido quimioterapia de forma reciente (82,8%) y en pacientes con neutropenia grave (79,3%). Setenta y cinco pacientes (51%) fallecieron en los primeros 30días; los factores de riesgo asociados fueron la neutropenia grave, un valor inferior a 70 en la escala de Karnofsky, presencia de choque séptico y no recibir los antifúngicos apropiados.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con cáncer que cursan con candidemia presentan una alta mortalidad relacionada con factores asociados a la neoplasia. Iniciar un tratamiento antifúngico lo antes posible incrementa la supervivencia de estos pacientes.

Candida bloodstream infection (CBSI) is a growing problem among patients with cancer receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy and extensive surgical procedures. It represents the fourth cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections in the United States, accounting for up to 10% of all bloodstream infections in hospitalized patients, and it has become a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with cancer.11,17

The crude mortality rate is about 40% (ranging between 20 and 50%), and lack of antifungal therapy is an independent factor associated with mortality.4,8,11

CBSI has been related with several risk factors, such as invasive procedures, intravenous catheters, parenteral nutrition, major surgery (particularly abdominal), immunosuppressive therapies, chronic dialysis, and Candida colonization.10,11 In patients with cancer, other risk factors, such as impairment of the immune system due to underlying malignancy and its treatment, chemotherapy, and mucosal barrier damage, are also related.5 On the other hand, the widespread use of antimicrobial prophylaxis, as well as of preemptive antifungal treatment, have contributed during the last years to a change in the epidemiology of Candida species isolated in these patients.5

The aim of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics related with CBSI, the Candida species identified, the clinical outcome at 30 days, and the risk factors associated with mortality in an 11-year period.

Materials and methodsWe included all Candida isolates from blood cultures reported between January 2010 and December 2020 in the Laboratory of Microbiology at the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INCan) in Mexico City, Mexico. INCan is a tertiary-care oncology center with 135 beds, 7000 hospital discharges and 37,000 chemotherapy sessions per year. The study was approved by the Institution's Ethics Committee (2020/0147). Being the study observational, an informed-consent waiver was granted.

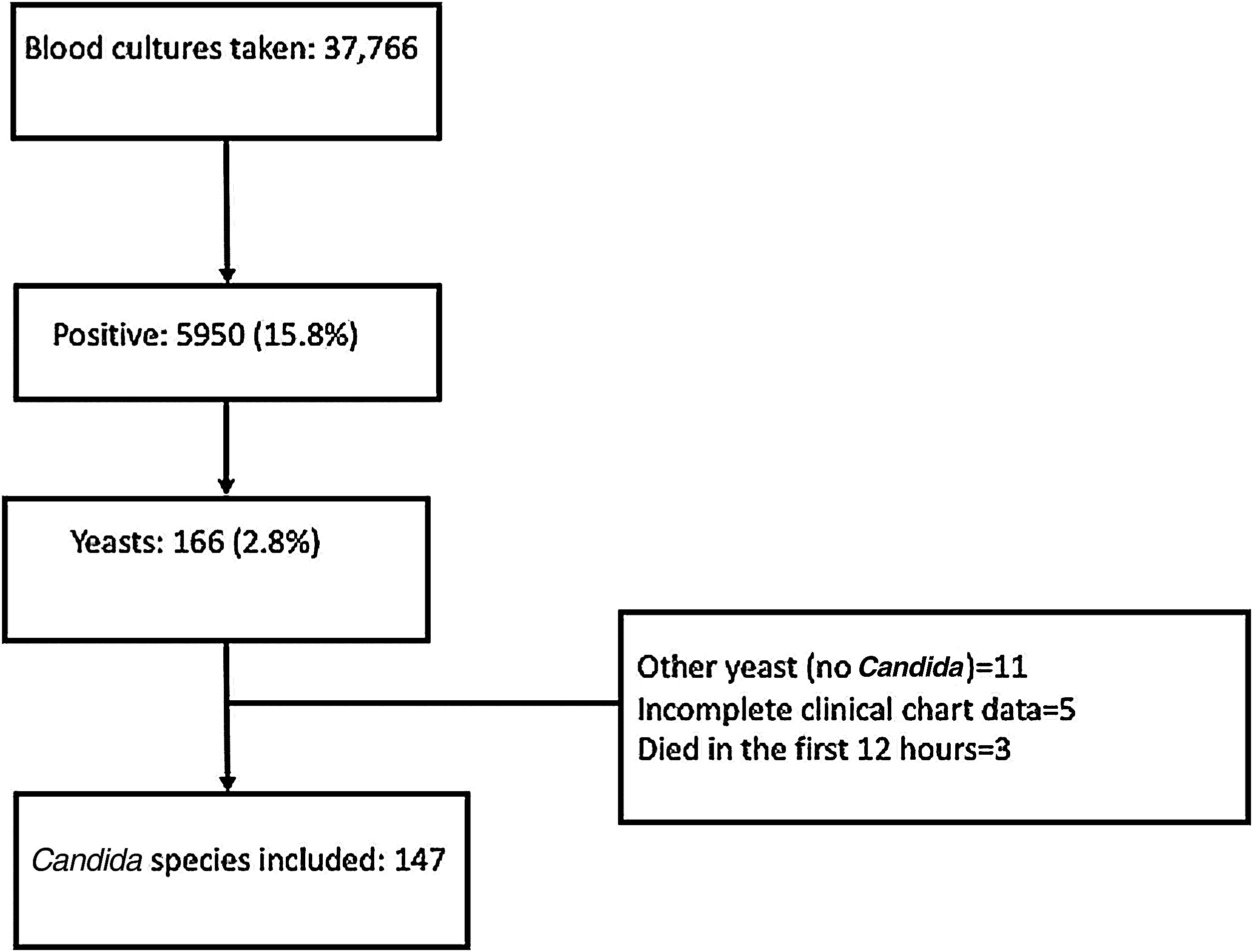

Patients in whom the yeast identified was not a Candida species, and those who died in the first 12h or for whom the clinical record was incomplete were not included. Only one strain per patient was included.

CBSI was defined as at least one blood culture positive for Candida, collected from either a central venous catheter (CVC) or a peripheral vein in a patient who had fever or other signs of infection.

Medical and laboratory records were retrospectively reviewed. Demographic, microbiological, and cancer-related data were registered. The variables recorded were the following: age, gender, comorbidities, type of cancer and stage, previous surgical procedure, hospitalization during the previous three months, chemotherapy, antifungals and antibiotics during the previous month, steroids, parenteral nutrition, severe neutropenia (≤500cell/mm3), days of neutropenia, mechanical ventilation, having a CVC, Candida species isolated, catheter removal, deep fungal infection and sites involved, days of hospitalization, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission, length of ICU stay, quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score (qSOFA), Karnofsky Performance Scale score, antifungal primary treatment, second antifungal therapy and the reason for change, and total days of antifungals. Severe sepsis was defined as sepsis associated with organ dysfunction, hypoperfusion, or hypotension. Septic shock was defined as sepsis-induced with hypotension despite adequate fluid administration, along with the presence of perfusion abnormalities.9 The survival outcome of the patients was evaluated at 72h and at day 30 from the time the candidemia was diagnosed.

CBSI was classified as follows: (a) Secondary, when a source of infection was documented; (b) Catheter-related, if the time to positivity of blood cultures was ≥2h when compared with cultures from blood obtained from the catheter lumen, and blood obtained from peripheral vein puncture, together with signs of systemic infection and no apparent source of the latter, except for the catheter, and (c) Unknown source, when neither secondary nor catheter-related infection were documented.

Candida identification was performed by Mass Spectrometry Especially Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption and Ionization-Time of Flight Mass (MALDI-TOF-MS; Microflex, Brukner, USA), and confirmed by BD Automated Phoenix™ (USA).

The antifungal susceptibility was not performed before 2015, and from that date on till 2020 it was done by means of Fungitest (Bio-RadTM, France); in the year 2020, Vitek®2 (bioMérieux, France) was the method performed.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were evaluated with the Chi-square or Fisher exact test. Candida species were classified into groups according to the most common species isolated. To compare continuous variables, parametric tests as Student t-distribution or ANOVA were used, and Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare non-parametric variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed to identify independent risk factors for 30-day mortality. Variables obtained from univariate analysis with p values<0.1 were included in the multivariate model in a staggered manner, including the variables progressively according to the highest statistical p-values obtained in the univariate analysis. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated for all emerging associations, considering a p-value of <0.05 significant. Kaplan Meier survival curve was assessed regarding the different Candida species. Data were analyzed employing STATA (ver. 14) statistical software.

ResultsFrom January 2010 to December 2020, 37,766 blood cultures were performed, 5950 (15.8%) were positive, and yeasts were isolated in 166 (2.8%). Nineteen patients were excluded: eleven had not a Candida isolate, five had an incomplete clinical chart, and three patients died within the 12h of arrival at the hospital. Flow chart is shown in Fig. 1.

One hundred forty-seven patients were included: the mean age of the patients was 46.7±17.8 years, and 64 (43.5%) were males. There were 78 (53.1%) patients with hematologic malignancies, and 69 (46.9%) had a solid tumor. Eighty (54.5%) patients had been recently diagnosed with cancer, 34 (23.1%) were in cancer progression, 14 (9.5%) in relapse and 19 (12.9%) in remission. Forty-one (27.9%) had a bloodstream infection during the previous 14 days, and 99 (67.3%) had received broad spectrum antibiotics during the previous three months (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics in patients with hematologic malignancies and solid tumors with a Candida bloodstream infection.

| Characteristic | Total | Hematologic malignancy | Solid tumor | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=147 (%) | n=78 (53.1%) | n=69 (46.9%) | ||

| Male | 64 (43.5) | 39 (50) | 25 (36.2) | 0.09 |

| Female | 83 (56.5) | 39 (50) | 44 (63.8) | |

| Mean age (years±s.d.)a | 46.7±17.8 | 39.8±17.4 | 54.5±14.8 | <0.001 |

| Clinical cancer status | ||||

| Recent diagnosis | 80 (54.5) | 51 (65.4) | 29 (42.1) | 0.004 |

| Progression | 34 (23.1) | 8 (10.2) | 26 (37.7) | <0.001 |

| Relapse | 14 (9.5) | 11 (14.1) | 3 (4.3) | 0.05 |

| Partial remission/stable disease | 5 (3.4) | 2 (2.6) | 3 (4.3) | 0.665 |

| Complete remission | 14 (9.5) | 6 (7.7) | 8 (11.6) | 0.575 |

| HSCTb | 5 (3.4) | 5 (6.4) | – | n/a |

| Autologous | – | 1 (1.2) | – | n/a |

| Allogeneic | – | 4 (5.1) | – | n/a |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| HIV | 3 (2) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.4) | 1.0 |

| Systemic hypertension | 16 (10.1) | 1 (1.3) | 15 (21.7) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (12.2) | 6 (7.7) | 12 (17.4) | 0.08 |

| Renal failure | 33 (22.5) | 11 (14.1) | 21 (30.4) | 0.01 |

| Liver disease | 30 (20.4) | 20 (25.6) | 10 (14.5) | 0.105 |

| Steroids | 60 (40.8) | 44 (56.4) | 16 (23.2) | <0.001 |

| Candiduria | 26 (17.7) | 13 (16.7) | 13 (18.8) | 0.730 |

| BSI during the previous 14 daysc | 41 (27.9) | 25 (32) | 16 (23.2) | 0.231 |

| Broad spectrum antibioticsd | 99 (67.3) | 58 (74.3) | 41 (59.4) | 0.05 |

| Cephalosporins | 36 (24.5) | 18 (23.1) | 18 (26.1) | 0.671 |

| Aminoglycosides | 22 (15) | 20 (25.6) | 2 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Carbapenems | 68 (46.3) | 39 (50) | 29 (42) | 0.333 |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam | 16 (10.9) | 13 (16.7) | 3 (4.3) | 0.01 |

| Vancomycin | 23 (15.6) | 12 (15.4) | 11 (15.9) | 0.926 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 9 (6.1) | 5 (6.4) | 4 (5.8) | 1.0 |

There were 122 (83%) patients with a CVC, 83 (56.5%) had received chemotherapy within the previous month, and 63 (42.9%) had severe neutropenia. Thirty-one (21.1%) patients had received antifungal therapy within the previous 14 days prior to Candida isolation in blood.

Candida albicans was the most frequent isolated species (n=54, 36.7%), followed by Candida glabrata (n=40, 27.2%) and Candida tropicalis (n=29, 19.7%). In nine of the eleven years studied, non-C. albicansCandida species predominated over C. albicans.

CBSI was classified as secondary in 47 (31.9%) cases: 43 were related with a previous surgery (33 abdominal, 6 urologic, two head/neck, one thoracic, and one in soft tissues). In 40 (27.2%) patients, CBSI episodes were classified as catheter-associated, thus all those catheters were removed. In 60 (40.8%) patients CBSI were classified as non-source documented. Clinical features according to the Candida species isolated are shown in Table 2.

Clinical characteristics related with the oncologic disease, and antifungal treatment for Candida bloodstream infection, classified by the Candida species isolated.

| Characteristics | Total (n=147) | C. albicans (n=54, 36.7%) | C. glabrata (n=40, 27.2%) | C. tropicalis (n=29, 19.7%) | C. parapsilosis (n=14, 9.5%) | Other species (n=10, 6.8%)a | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-source documented | 60 (40.8) | 20 (37.1) | 10 (25) | 22 (75.9) | 3 (21.4) | 5 (50) | <0.001 |

| Secondary candidemiab | 47 (31.9) | 18 (33.3) | 21 (52.5) | 2 (6.9) | 5 (35.7) | 1 (10) | <0.001 |

| Abdominal source | 38 (60) | 15 (27.7) | 18 (45) | 2 (6.9) | 6 (42.9) | 1 (10) | 0.002 |

| Head and neck | 4 (5.7) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (7.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Urinary source | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Empyema | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| CVC-related | 40 (27) | 16 (29.6) | 9 (22.5) | 5 (17.2) | 6 (42.9) | 4 (40) | 0.335 |

| Hematologic neoplasms | 78 (53.1) | 27 (50) | 16 (40) | 23 (79.3) | 6 (42.9) | 6 (60) | 0.01 |

| Leukemia | 44 (29.9) | 15 (27.8) | 5 (12.5) | 16 (55.2) | 5 (35.7) | 3 (30) | 0.004 |

| Lymphoma | 27 (18.4) | 8 (14.8) | 8 (20) | 7 (24.1) | 1 (7.1) | 3 (30) | 0.493 |

| Otherc | 7 (4.8) | 4 (7.4) | 3 (7.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Solid tumors | 69 (46.9) | 27 (50) | 24 (60) | 6 (20.7) | 8 (57.1) | 4 (40) | 0.01 |

| Gastrointestinal | 28 (19) | 7 (3) | 11 (27.5) | 3 (10.3) | 4 (28.6) | 3 (30) | 0.185 |

| Gynecologic | 24 (16.3) | 12 (22.2) | 8 (20) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (14.3) | 0 | n/a |

| Urologic | 8 (5.4) | 5 (9.3) | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 1 (10) | n/a |

| Otherd | 8 (5.4) | 3 (14.8) | 3 (7.5) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | n/a |

| Chemotherapy | 83 (56.5) | 29 (53.7) | 19 (47.5) | 24 (82.8) | 5 (35.7) | 6 (60) | 0.01 |

| Neutropenia (<500/mm3) | 63 (42.9) | 20 (37) | 12 (30) | 23 (79.3) | 2 (14.3) | 6 (60) | <0.001 |

| Prolonged neutropenia | 26 (17.7) | 8 (14.8) | 7 (17.5) | 7 (24.1) | 0 | 4 (40) | n/a |

| Previous antifungal treatmente | 31 (21.1) | 11 (20.4) | 5 (12.5) | 6 (20.7) | 5 (25.7) | 4 (40) | 0.049 |

| Previous surgeryf | 57 (38.8) | 24 (44.4) | 20 (50) | 5 (17.2) | 7 (50) | 1 (10) | 0.006 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 34 (23.1) | 19 (35.2) | 5 (12.5) | 4 (13.8) | 5 (35.7) | 1 (10) | 0.028 |

| Central venous catheter (CVC) | 122 (83) | 44 (81.5) | 34 (85) | 23 (79.3) | 12 (85.7) | 9 (90) | 0.08 |

| Length of hospital stay (days)g | 25.3±16.5 | 23.6±15.9 | 20.5±16.4 | 31.2±15.4 | 30.7±17.3 | 29.9±16.8 | 0.991 |

| ICU admissionh | 63 (42.9) | 21 (38.9) | 20 (50) | 12 (41.4) | 8 (57.1) | 2 (20) | 0.320 |

| Length ICU stay (days)g | 9.7±7.8 | 9.9±4.5 | 7.8±6.5 | 10.1±8.9 | 11.2±9.7 | 17±12 | 0.624 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 51 (34.7) | 19 (35.2) | 15 (37.5) | 8 (27.6) | 7 (50) | 2 (20) | 0.480 |

| qSOFA ≥2i | 37 (25.2) | 9 (16.7) | 18 (45) | 4 (13.8) | 3 (21.4) | 3 (30) | 0.01 |

| Severe sepsis | 58 (39.5) | 21 (38.9) | 16 (40) | 13 (44.8) | 5 (35.7) | 3 (30) | 0.065 |

| Antifungal treatment ≥2 days | 101 (68.7) | 30 (55.6) | 30 (75) | 23 (79.3) | 12 (85.7) | 6 (60) | 0.06 |

| Days of antifungal therapyj | 14 (6, 18) | 11 (3, 16) | 12 (7, 18) | 17 (10, 20) | 14 (4, 15) | 19 (12, 24) | 0.01 |

| First-line antifungal therapy | 127 (86.4) | 46(85.2) | 33 (82.5) | 27 (93.1) | 14 (100) | 7 (70) | 0.185 |

| Caspofungin | 76 (51.7) | 22 (40.7) | 25 (62.5) | 15 (51.7) | 9 (64.3) | 5 (50) | 0.247 |

| Amphotericin B deoxycholate | 30 (20.4) | 13 (24.1) | 6 (15) | 10 (34.5) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | n/a |

| Fluconazole | 20 (13.6) | 11 (20.4) | 2 (5) | 1 (3.5) | 4 (28.6) | 2 (20) | 0.026 |

| Posaconazole | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.5) | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Second-line antifungal therapy | 56 (38.1) | 25 (46.3) | 11 (27.5) | 13 (44.8) | 3 (21.4) | 4 (40) | 0.232 |

| Fluconazole | 34 (23.1) | 18 (33.3) | 6 (15) | 7 (24.1) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (20) | 0.126 |

| Amphotericin B deoxycholate | 11 (7.5) | 4 (7.4) | 2 (5) | 3 (10.3) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (10) | 0.06 |

| Caspofungin | 8 (5.4) | 3 (14.8) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (10) | 0.146 |

| Liposomal amphotericin B | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.5) | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Posaconazole | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Voriconazole | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Mortality at 72h | 24 (16.3) | 13 (24.1) | 6 (15) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (20) | 0.226 |

| Mortality at 30 days | 75 (51) | 30 (55.6) | 22 (55) | 12 (41.4) | 5 (35.7) | 6 (60) | 0.487 |

Other species: one Candida dubliniensis, one Candida haemulonii, one Candida lusitaniae, and one Candida utilis.

Other hematological malignancies: five patients with multiple myeloma and two with myelodysplastic syndrome.

There were 29 (19.7%) patients with deep fungal infection. The sites involved were: pleura/lung (n=9), peritoneum (n=6), spleen (n=5), kidney (n=3), liver (n=3), eye (n=2), skin (n=2), and central nervous system (n=1). Twenty-two (14.9%) patients had persistent candidemia; in seven patients, a transthoracic echocardiography was performed, and no endocarditis was present according to the data reported.

One hundred twenty-seven (86.4%) patients received antifungal therapy: 76 (59.8%) caspofungin, 30 (23.6%) amphotericin B deoxycholate (AmB-D), and 20 (15.7%) fluconazole. In 56 (38.1%) patients, the antifungal was changed to a second-line treatment; de-escalation was the main reason in 36 (64.2%) (Table 1).

Antifungal susceptibility was performed for 61 isolates (from the date it became available). Fifty-seven were tested by means of Fungitest, and four with Vitek®2. Susceptibility to 5-flurocytosine was 59/61 (96.7%), for AmB-D 57/58 (98.3%), and for fluconazole, 43/57 (75.4%). Resistance to fluconazole was reported in 5/57 (8.8%), and intermediate sensitivity in 9/57 (15.8%). Only four strains were tested for caspofungin and micafungin; all were susceptible.

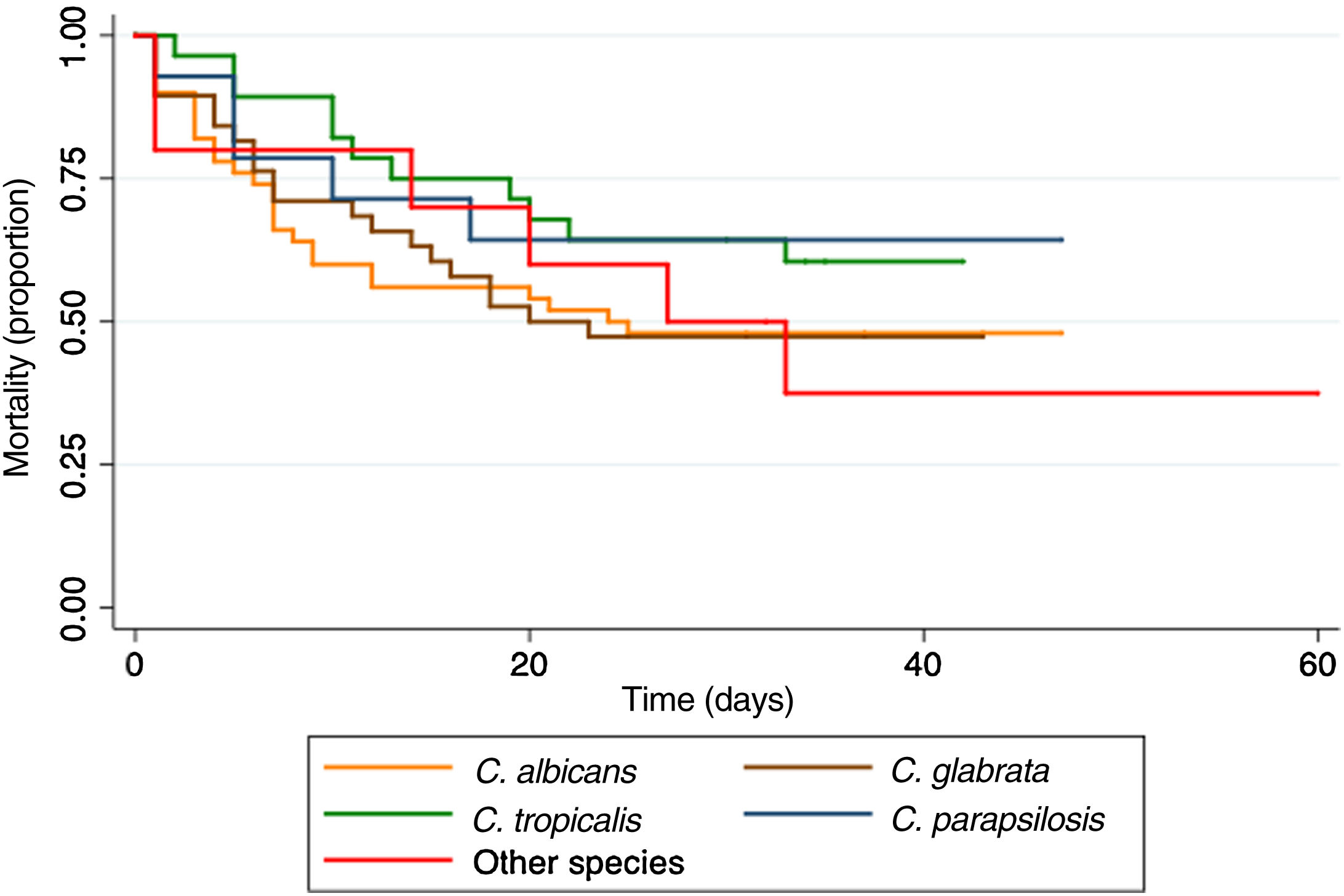

Twenty-four (16.3%) patients died within the first 72h, and 75 (51%) within the first 30 days. The Kaplan–Meier curve shows the mortality according to the Candida species infection (Fig. 2).

In the univariate analysis, cancer in progression or relapse, severe neutropenia, Karnofsfky Performance Scale score<70, severe sepsis or septic shock, unknown source or secondary CBSI, non-CVC removal, and not receiving appropriate antifungal treatment for ≥2 days were the risk factors associated with 30-day mortality. In the multivariate analysis, severe neutropenia (OR 3.16, 95%CI 1.18–8.42), Karnofsky Performance Scale score<70 (OR 3.75, 95%CI 1.47–9.52), severe sepsis or septic shock (OR 3.96, 95%CI 1.53–10.19), and not receiving appropriate antifungal treatment for ≥2 days (OR 3.99, 95%CI 1.35–11.84) were the risk factors associated with 30-day mortality (Table 3).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of several variables for predicting mortality at 30-days in patients with CBSI.

| Characteristic | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive | Dead | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| (n=72, 49%) | (n=75, 51%) | |||||

| Age<60 years | 58 (80.6) | 53 (70.7) | 1.71 (0.74–4.02) | 0.163 | – | – |

| Age≥60 years | 14 (19.4) | 22 (29.3) | ||||

| Solid tumor | 37 (51.4) | 32 (42.7) | 1.03 (0.49–2.16) | 0.917 | – | – |

| Hematologic malignancy | 35 (48.6) | 43 (57.3) | ||||

| Recent diagnosis, remission | 54 (72) | 45 (60) | 2 (0.93–4.32) | 0.052 | 1 | 0.066 |

| Progression or relapse | 18 (25) | 30 (40) | 2.68 (0.93–7.68) | |||

| Non-severe neutropenia | 51 (70.8) | 33 (44) | 3.09 (1.48–6.49) | 0.001 | 1 | 0.021 |

| Severe neutropenia | 21 (29.2) | 42 (56) | 3.16 (1.18–8.42) | |||

| Karnofsky Performance Scale score ≥70 | 43 (59.7) | 24 (32) | 3.15 (1.52–6.56) | <0.001 | 1 | 0.005 |

| Karnofsky Performance Scale score<70 | 29 (40.3) | 51 (68) | 3.75 (1.47–9.52) | |||

| Non-severe sepsis | 56 (77.8) | 33 (44) | 4.45 (2.05–9.8) | <0.001 | 1 | 0.004 |

| Severe sepsis or septic shock | 16 (22.2) | 42 (56) | 3.96 (1.53–10.19) | |||

| Candida albicans | 24 (33.3) | 30 (40) | 0.75 (0.36–1.55) | 0.402 | – | – |

| Other species of Candida | 48 (66.7) | 45 (60) | ||||

| CBSI-catheter-associated | 29 (40.3) | 11 (14.7) | 3.92 (1.67–9.59) | <0.001 | 1 | 0.134 |

| Secondary or unknown CBSI source | 43 (59.7) | 64 (85.3) | 2.44 (0.75–7.87) | |||

| Non-deep fungal infection | 58 (80.6) | 60 (80) | 1.03 (0.42–2.54) | 0.932 | – | – |

| Deep fungal infection | 14 (19.4) | 15 (20) | ||||

| Appropriate antifungal treatment ≥48h | 62 (86.1) | 39 (52) | 5.72 (2.41–14.3) | <0.001 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Non-antifungal treatment or <48h | 10 (13.9) | 36 (48) | 3.99 (1.34–11.84) | |||

| Non-modified antifungal therapy or de-escalation | 62 (86.1) | 65 (86.7) | 0.95 (0.33–2.75) | 1 | – | – |

| Antifungal therapy modified (escalation/toxicity) | 10 (13.9) | 10 (13.3) | ||||

| Catheter removal during the first 48ha | 36 (58.1) | 16 (26.7) | 3.81 (1.66–8.8) | <0.001 | 1 | 0.384 |

| Non-catheter removal | 26 (41.9) | 44 (73.3) | 1.54 (0.58–4.1) | |||

It has been accepted that blood stream infections are a major cause of complications in patients with cancer; blood stream infections delay chemotherapy, prolongs hospital stays, leads to suboptimal antineoplastic treatment, increases mortality, and raises healthcare costs.13,14 However, the majority of these episodes are due to bacteria, and much less frequently are caused by yeasts, the most frequent of which are Candida. In our cohort, there was a similar distribution between patients with solid tumors and those with hematologic neoplasms, with a higher proportion of patients with recent cancer diagnosis, mainly in hematology patients.

Some risk factors that have been reported for candidemia are the presence of CVC, parenteral nutrition, steroids, recent surgery, and previous use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.21 In this series, we found that a large proportion of patients had a recent oncological diagnosis, in addition to several risk factors related to the oncological disease per se, such as the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, surgery, CVC and having received chemotherapy.

Two decades ago, non-C. albicans isolates accounted for fewer than 20% of all Candida species recovered from blood.20 In recent years, there has been a clearly increasing trend of non-C. albicansCandida species isolation worldwide.20 In the Latin- America region, more than 80% of the cases are caused by three species: C. albicans; C. tropicalis, and Candida parapsilosis.3,4 In a previous research performed in Mexico, non-C. albicans species represented 68% of the Candida isolates, being C. parapsilosis the most frequent (37.9%).7 In another study, which included only patients with cancer, C. albicans represented 54.5%, followed by C. tropicalis (21.5%) and C. parapsilosis (15.7%).21 In our study, C. albicans was the most common species (36.7%), followed by C. glabrata (27.2%) and C. tropicalis (19.7%). Considering other reports in patients with cancer, C. glabrata was the most common species in patients with hematologic malignancies, while C. albicans has been reported more frequently in patients with solid tumors.3,12 In this study, we found C. tropicalis in patients with hematologic malignancies mainly, and C. glabrata in those with solid tumors.

CBSI classified as unknown source were mostly diagnosed in patients with severe neutropenia. Modification in the gut microbiota, alteration in the barrier function of epithelial cells, and intestinal inflammation secondary to myelosuppressive chemotherapy, in addition to administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, are factors that might interact and create conditions for Candida translocation from gut to intravascular space.1,18,19,22,23

We found that the majority of our patients received caspofungin as the first antifungal therapy, followed by fluconazole and AmB-D. Unlike what is recommended in international guidelines,16 AmB-D was the most widely used amphotericin due to its ample availability in Mexico and its lower cost when compared with lipid formulations of amphotericin B. Step-down therapy was administered in 64.3% of our patients, with a reduction on the exposure to echinocandins and the minimization of any selective pressure on fungal isolates.6,16

Mortality in the first 72h had been previously reported in 20%11; in this study, it was 16.3%. Overall case fatality at 30 days was 51%, similar to that in other reports in patients with cancer (49.1%).21 We found that patients with C. parapsilosis had the lowest mortality (35.7%), as described in other studies.2

The risk factors associated with 30-day mortality that we found, ordered from the highest to the lowest risk, were the following: not receiving adequate antifungal therapy in the first 48h, severe sepsis or septic shock, low Karnofsky Performance Scale score (<70) and severe neutropenia. Other reports mention septic shock as a predictor of mortality.15,21 An early clinical suspicion of candidemia and starting an appropriate antifungal therapy in the first hours are essential to reduce the mortality.

The limitations of this study have been those related with an observational, retrospective study, and that the study was performed at a single oncologic center. Besides, the data collected on antifungal susceptibility covers the time period since 2015 only. Study strengths included that these patients comprise a captive population that allows a close follow-up. There are few studies that have explored CBSI in patients with cancer. Therefore, the information gathered is relevant as it allows the characterization of certain clinical factors present in the oncologic population.

Patients with CBSI presented a high mortality related to the severity of the patient's condition, being the risk factors involved unmodifiable in the majority of the cases. Some risk factors for candidemia are linked to the oncological disease, such as chemotherapy, surgery, long-term CVC, neutropenia, and the frequent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

However, mortality was also related with not receiving adequate antifungal treatment in the first hours; thus, suspecting the diagnosis and starting an empirical antifungal therapy in those patients with risk factors are essential for improving survival rates.

Funding sourceThis study was supported with internal funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they do not have any conflict of interest.

Microbiology laboratory of INCan.