There is increased interest in studying ATTR-CA, a pathology that primarily affects patients of geriatric age and is frequently underdiagnosed. We aim to establish the prevalence of ATTR-CA in a cohort of patients with a history of HFpEF and to describe its characteristics.

MethodsWe conducted a prospective observational study. Patients ≥75 years, clinical history of HFpEF, atrial dilation ≥34ml/m2 and left ventricular wall thickening >13mm, were included. Demographic and analytical parameters were collected, and a comprehensive geriatric assessment was performed, along with a transthoracic echocardiogram and cardiac scintigraphy. Finally, telephone follow-up was carried out at 6 and 12 months.

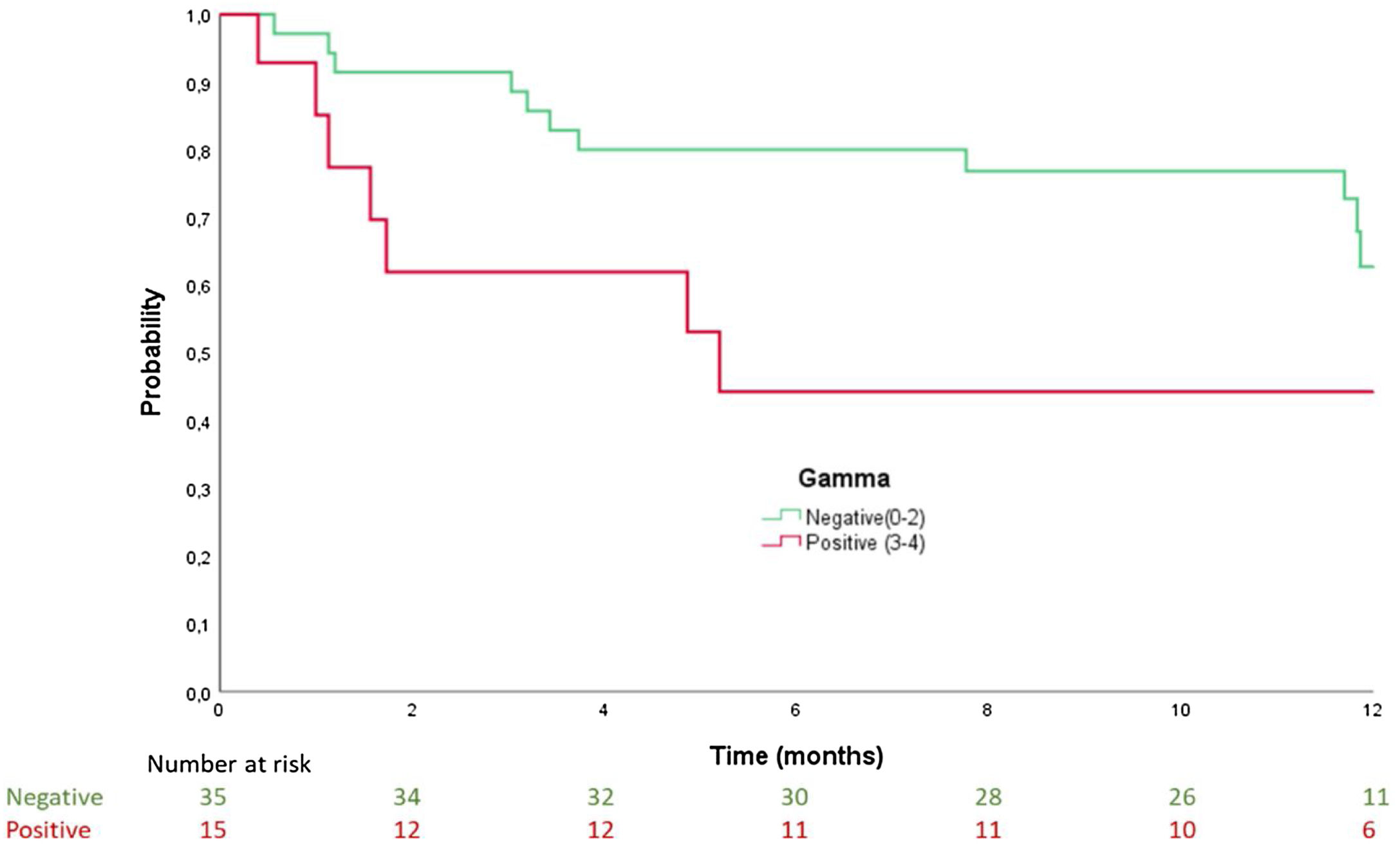

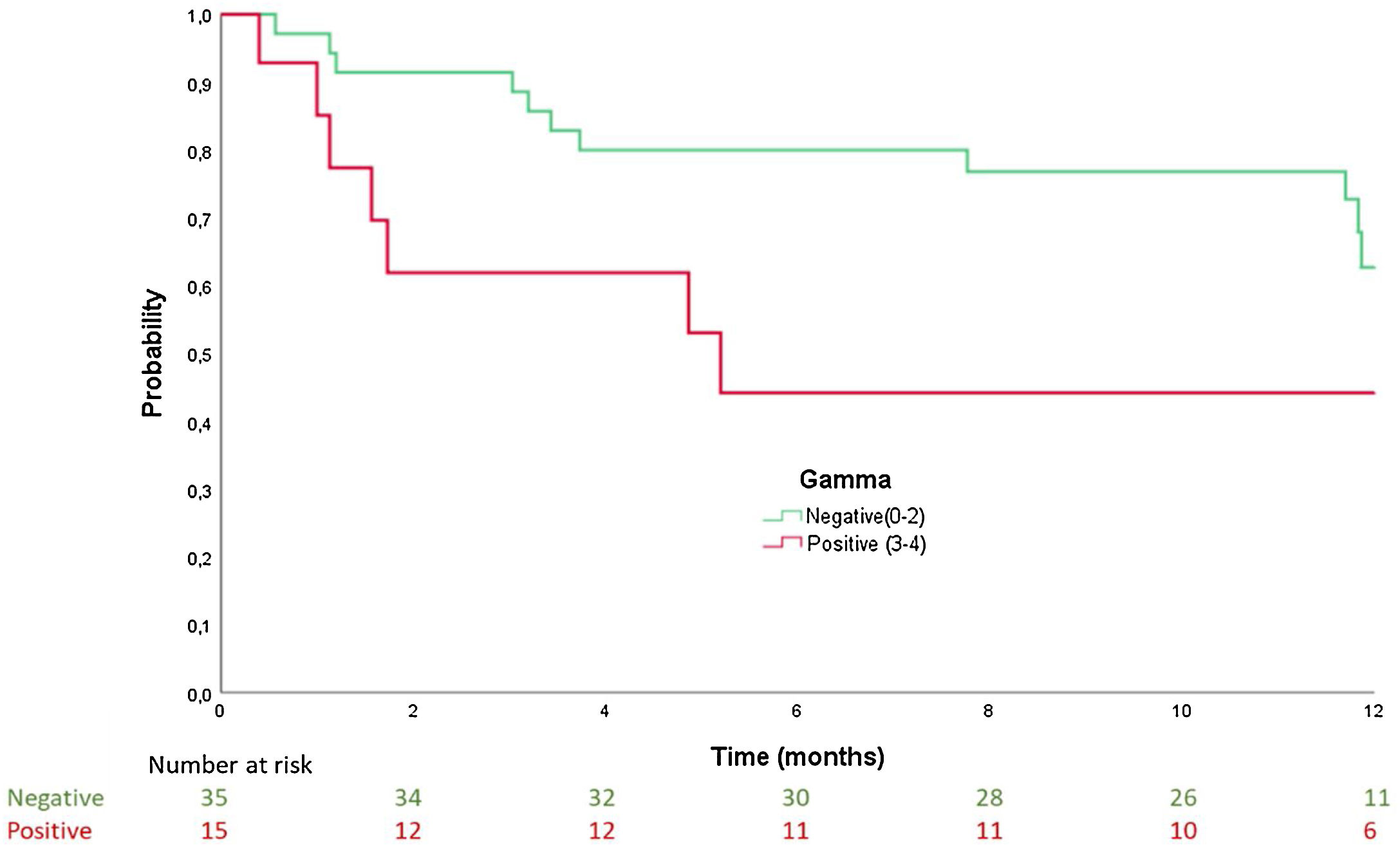

Results50 patients were recruited, mean age 86±6 years, 54% women. Age and functional class (I–II vs. III–IV) were factors associated with presenting with ATTR-CA. Patients with positive scintigraphy had a median time to admission of 5.2 months (confidence interval [CI] 95% 0–10.9), while in those with negative scintigraphy, it was 12.2 months (95% CI 11.7–12.8); log-rank: p=0.064. Patients with positive scintigraphy had a median time to the combined endpoint (death and readmission) of 1.9 months (95% CI 0–6.1), and patients with negative scintigraphy of 11.9 months (95% CI 11.7–12); log-rank: p=0.027.

ConclusionsATTR-CA appears to be a prevalent etiology in elderly patients within the spectrum of HFpEF. Patients with a diagnosis of ATTR-CA had a shorter time to admission for HF and the combined event of death and admission than patients with a negative result on scintigraphy.

Existe un interés creciente por el estudio de AC-TTR, siendo esta una patología que afecta fundamentalmente a pacientes de edad avanzada y que es frecuentemente infradiagnosticada. Nuestro objetivo fue establecer la prevalencia de AC-TTR en una cohorte de pacientes con historia de ICFEp y describir sus características.

MétodosEstudio observacional prospectivo. Se incluyeron pacientes ≥75 años, con historia clínica de ICFEp, dilatación auricular ≥34ml/m2 y engrosamiento de la pared del ventrículo izquierdo >13mm. Se recogieron datos analíticos y demográficos, así como de la valoración geriátrica integral y se realizó un ecocardiograma transtorácico y una gammagrafía cardiaca. Finalmente se realizó seguimiento telefónico a los 6 y 12 meses.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 50 pacientes, edad media 86±6 años, 54% mujeres. La edad y la clase funcional NYHA (I-II vs. III-IV) se asociaron con mayor riesgo de presentar AC-TTR. Los pacientes con gammagrafía positiva tuvieron una mediana de tiempo al ingreso de 5,2 meses (intervalo de confianza [IC] 95% 0-10,9), frente a aquellos con gammagrafía negativa que fue de 12,2 meses (IC 95% 11,7-12,8); log-rank: p=0,064. Los pacientes con gammagrafía positiva presentaron una mediana de tiempo al evento combinado (muerte y reingreso) de 1,9 meses (IC 95% 0-6,1), mientras que en aquellos con resultado negativo fue de 11,9 meses (IC 95% 11,7-12); log-rank: p=0.027.

ConclusionesLa AC-TTR supone una etiología prevalente de insuficiencia cardiaca, dentro del espectro de la ICFEp, en pacientes de edad avanzada. Los individuos con diagnóstico de AC-TTR presentaron un menor tiempo al ingreso por insuficiencia cardiaca y al evento combinado de muerte y reingreso frente a aquellos pacientes con resultado negativo en la gammagrafía.

Transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis (ATTR-CA) is an infiltrative cardiomyopathy caused by extracellular accumulation of insoluble TTR-derived amyloid fibers in the myocardium.1

Two variants of ATTR-CA are described, a wild-type (ATTRwt-CA) and a hereditary (ATTRh-CA) form. ATTRwt-CA, formerly called over 70 years of age and typically presents with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).2 This disease has been identified in approximately 13% of patients with HFpEF and in up to 16% of patients with aortic stenosis (AS) referred for implantation of a transcatheter aortic valve prosthesis (TAVI).3

There is significant difficulty in detecting ATTR-CA in elderly patients. On the one hand, the anatomical changes that occur with age, such as the thickening of the septum and the ventricular wall, and on the other hand, the associated comorbidities, such as hypertension, AS and coronary artery disease, along with a low clinical suspicion associated with this disease, cause a diagnostic delay to occur in a high percentage of cases.4,5 Therefore, it is necessary to improve clinical suspicion to approach the correct diagnosis of ATTR-CA, mainly among patients with left ventricular (LV) wall thickening >12mm, an age >60 years and a new diagnosis of HFpEF.3

Diastolic function is also altered in the geriatric population as a consequence of ventricular stiffness and high coincidence with other chronic diseases. The prevalence of HFpEF in elderly people, described in different population studies, ranges between 1.14% and 5.4%.6

Various publications have shown that frailty is a frequent syndrome among patients diagnosed with heart failure (HF), with prevalences between 19 and 52%, according to the different studies and the screening methods used; such rates are much higher than those in geriatric patients without a diagnosis of HF.7 This relationship could be justified because the two processes share predisposing pathophysiological abnormalities, such as high comorbidity, advanced age, increased hospitalizations, functional decline and sarcopenia. It could therefore be assumed that frailty would also constitute a prevalent syndrome in elderly patients diagnosed with cardiac amyloidosis.

For this reason, there is increased interest in studying ATTR-CA, a pathology that primarily affects patients of geriatric age and is frequently underdiagnosed, even though it constitutes a prevalent etiology within the spectrum of HFpEF. Likewise, it was considered appropriate to include elements of frailty screening and comprehensive geriatric assessment in this cohort of patients and include them in the analysis. We found multiple publications on this topic that have studied the incidence and impact of frailty in HF, but there are very few studies that relate both entities.

Therefore, the objectives of our study were to establish the prevalence of ATTR-CA in a cohort of patients with a history of HFpEF and specific echocardiographic criteria and to describe its characteristics (including functional assessment parameters and frailty) in order to identify the factors associated with a greater probability of presenting with ATTR-CA within our sample as well as their relationship over time with the combined variable of mortality and readmission.

MethodsA prospective observational cohort study was designed and carried out at a secondary university hospital. Patients were included from October 2019 to December 2020.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Universidad Alfonso X el Sabio and was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed the informed consent.

Patient recruitment was carried out during cardiology consultations with patients who underwent a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) at the request of the Cardiology, Internal Medicine or Geriatrics Services.

The included patients were ≥75 years old and had echocardiographic findings of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥50%, left atrial dilation ≥34ml/m2 and ventricular hypertrophy defined as end-diastolic thickening of the LV wall >13mm in the long parasternal axis.

All patients with a previous diagnosis that could indicate moderate or severe ventricular hypertrophy were excluded; such conditions included poorly controlled high blood pressure (HBP) (mean values in daytime ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) above 139/89mmHg), moderate or severe aortic valve disease, a mechanical or biological valve prostheses, history of hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy, and history of significant coronary artery disease, defined as prior myocardial infarction, stenosis of a left main vessel or of the proximal anterior descending artery, or significant stenosis in two coronary arteries.

Demographic and analytical parameters were collected, and a geriatric specialist doctor carried out a comprehensive geriatric assessment, which included the determination of different variables, namely, basic activities of daily living (BADL) using the Barthel Index8; instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) using the Lawton IADL Scale9–11; frailty measurement using the short physical performance battery (SPPB)12 and Fried phenotype,13 classifying patients as fragile/prefrail or robust; a history of dementia and/or cognitive impairment; a history of repeated falls (defined as 2 or more falls in the previous six months); a history of depression according to DSM-V criteria14; and comorbidity measured by the Charlson index.15

The ultrasound study was performed using a Philips Affiniti 70 ultrasound machine. LVEF was quantified using the Teichholz method. HFpEF was considered when LVEF was ≥50%. The thickness of the interventricular septum and the posterior wall of the LV was assessed in end diastole in the long parasternal axis.16

Likewise, cardiac scintigraphy was carried out using a Millennium VG Gamma camera, with two heads for Spect and low energy and high resolution collimators (LEHR). The radiopharmaceutical used was 99mTc-DPD, administered intravenously at a dose of 740MBq (20mCi), which was adjusted for patients with renal insufficiency and advanced age. Two nuclear physicians blindly and independently visually analyzed the grayscale images. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The intensity of deposition in the myocardium was graduated according to a visual scale of 0–3 points. The test was considered positive when it reflected a moderate to severe degree of uptake in both ventricles (scores 2 and 3).17,18

All patients with a positive scintigraphy result were recommended to undergo a genetic study consisting of a sequence analysis and search for mutations in the complete coding regions of the gene.

Finally, telephone follow-up was carried out at 6 and 12 months, during which information on survival and readmissions that occurred within those periods were obtained, consulting the hospitalization reports via the electronic system. Admission for HF was defined as hospitalization with a main diagnosis of HF according to the criteria of the ICD-10 (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems).

Statistical methodsCategorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages (%), and continuous variables are expressed as the mean and SD or median and IQR (percentile 25–75) according to their distribution. The normality of continuous data was checked using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The differences between gamma groups (negative/positive) for qualitative variables were examined using the chi-square test, with the likelihood ratio correction or Fisher's exact test if small samples were used, and the differences for continuous variables were examined using independent samples t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate.

Curves for mortality and hospital admission for congestive heart failure (CHF) or combined events were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and comparisons between groups were performed using the log-rank test. Moreover, univariate and multivariate Cox proportional regression analyses were performed using the stepwise forward method.

The factors associated with positive gamma were studied using binary logistic regression and univariate and multivariate analyses using the stepwise forward method.

The results were considered significant at p values <0.05. All data were analyzed with SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

ResultsGeneral characteristics of the sampleDuring the study period, 50 patients were recruited, of whom 30% (N: 15) had positive scintigraphy compatible with ATTR-CA. The mean age was 86±6 years, and 54% of the patients were women (N: 27). The majority of patients (62%) were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II–III at the time of diagnosis. The most frequent comorbidities were HBP (64%), atrial fibrillation (AF) (64%), diabetes mellitus (36%), acute cerebrovascular accident (14%) and ischemic heart disease (10%). The median Charlson index value was 2 points (1–3). In the comprehensive geriatric assessment, the most prevalent geriatric syndromes in our sample were dementia (36%), repetitive falls (30%) and depression (20%). Forty-eight percent of the patients had moderate or severe dependence in BADL, and the median Barthel Index score was 93 (79–98). The median score on the Lawton IADL Scale was 4 (0–6).

Regarding the assessment of frailty, the median SPPB score was 6 points (3–11), and 60% (n: 9) of patients had a diagnosis of frailty according to the Fried phenotype (26.7% prefrail; n: 4) (Table 1). Forty percent were admitted due to decompensation of HF, with a median of 11 months (3.2–11.9) from inclusion to the first admission. Furthermore, 10% had 2 or more admissions for HF. Twenty-four percent of patients died during the one-year follow-up, with a median of 11.8 months (8.5–12) from diagnosis to death (Table 2).

General description of the sample and by groups according to the scan result.

| Total (n=50) | − Scintigraphy (n=35) | + Scintigraphy (n=15) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 86.1±6.2 | 84.3±6.1 | 90.1±4.4 | 0.002 |

| Female | 27 (54.0) | 21 (60.0) | 6 (40.0) | 0.193 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9±5.4 | 26.1±5.1 | 25.5±6.1 | 0.741 |

| Functional class (NYHA) | 0.012 | |||

| I | 9 (18.0) | 7 (20.0) | 2 (13.3) | |

| II | 21 (42.0) | 19 (54.3) | 2 (13.3) | |

| III | 10 (20.0) | 5 (14.3) | 5 (33.3) | |

| IV | 10 (20.0) | 4 (11.4) | 6 (40.0) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| HBP | 32 (64.0) | 23 (65.7) | 9 (60.0) | 0.700 |

| Dyslipidemia | 7 (14.0) | 6 (17.1) | 1 (6.7) | 0.659 |

| Diabetes | 18 (36.0) | 13 (37.1) | 5 (33.3) | 0.797 |

| Coronary heart disease | 5 (10.0) | 4 (11.4) | 1 (6.7) | 0.999 |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 1 (56.7) | 0.300 |

| Stroke | 7 (14.0) | 4 (11.4) | 3 (20.0) | 0.415 |

| Charlson index | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.598 |

| Laboratory test results | ||||

| Glomerular filtration (MDRD) | 58 (42–60) | 60 (45–60) | 58 (39–60) | 0.854 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.8±1.7 | 12.8±1.7 | 12.9±1.6 | 0.947 |

| Electrocardiogram | ||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.368 | |||

| Paroxysmal | 13 (26.0) | 11 (31.4) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Permanent | 19 (38.0) | 12 (34.3) | 7 (46.7) | |

| Geriatric variables | ||||

| Dementia | 18 (36.0) | 13 (37.1) | 5 (33.3) | 0.797 |

| Falls | 15 (30.0) | 12 (34.3) | 3 (20.0) | 0.502 |

| Depression | 10 (20.0) | 10 (28.6) | 0 | 0.022 |

| Frailty (Fried phenotype) | 0.642 | |||

| Robust | 9 (18.0) | 7 (20.0) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Pre-frail | 16 (32.0) | 12 (34.3) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Frail | 25 (50.0) | 16 (45.7) | 9 (60.0) | |

| SPPB | 6 (3–11) | 7 (4–11) | 4 (2–10) | 0.077 |

| Lawton IADL Scale | 4 (0–6) | 5 (0–7) | 0 (0–6) | 0.154 |

| Barthel index | 93 (79.5–98) | 95 (80–98) | 83 (46–98) | 0.162 |

| BADL | 0.388 | |||

| Independent | 11 (22.0) | 8 (22.9) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Mild dependence | 15 (30.0) | 12 (34.3) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Moderate dependence | 17 (34.0) | 12 (34.3) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Severe dependence | 7 (14.0) | 3 (8.6) | 4 (26.7) | |

Values of n (%) in the qualitative variables. Mean±S.D. in the quantitative variables that are close to the normal and median (p25–p75) in which they do not fit this distribution. BMI: body mass index; HBP: high blood pressure; SPPB: short physical performance battery; IADL: instrumental activities of daily living; BADL: basic activities of daily living.

Clinical prognostic variables.

| Total (n=50) | − Scintigraphy (n=35) | + Scintigraphy (n=15) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure (readmission) | 20 (40.0) | 13 (37.1) | 7 (46.7) | 0.529 |

| Number of readmissions | 0.339 | |||

| 0 | 30 (60.0) | 22 (62.9) | 8 (53.3) | |

| 1 | 15 (30.0) | 11 (31.4) | 4 (26.7) | |

| ≥2 | 5 (10.0) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Death | 12 (24.0) | 8 (22.9) | 4 (26.7) | 0.999 |

| Time (months) from diagnosis to death* | 11.8 (8.5–12.0) | 11.7 (8.5–12.1) | 11.8 (4.1–12.0) | 0.849 |

| Combined endpoint | 28 (56.0) | 17 (48.6) | 11 (73.3) | 0.106 |

| Time (months) from diagnosis to combined endpoint** | 10.9 (3.2–11.9) | 11.7 (4.2–11.9) | 1.9 (1.0–11.7) | 0.019 |

Values of n (%) in the qualitative variables.

Of all the patients in our sample with a positive result on cardiac scintigraphy, 7 patients underwent genetic testing (3 patients died during follow-up, and 5 rejected the test). None of the patients analyzed harbored mutations in the gene that encodes TTR, so all cases were considered ATTRwt-CA.

Patients with ATTR-CA (+ scintigraphy) versus other etiologies of HFpEF (− scintigraphy) in our sampleWhen the two groups, those with a positive scan versus those with a negative scan, were compared, it was observed that the patients with a positive result were older (90±4 vs. 84±6; p=0.002). Likewise, patients who subsequently presented with cardiac scintigraphy compatible with ATTR-CA were in a worse functional class at the time of inclusion (NYHA III–IV 73.3% vs. 25.7%; p=0.012). No statistically significant difference was observed in the degree of frailty expressed by the Fried phenotype or in the Barthel index and degree of dependence in BADL between the two groups of patients. However, there was a tendency towards lower scores on the SPPB and therefore a higher degree of frailty in patients with a diagnosis of ATTR-CA (4 [2–10] vs. 7 [4–11]; p=0.077). During the one-year follow-up, 4 patients (26.7%) in the ATTR-CA group and 8 patients (22.9%) in the other group (different etiologies of HFpEF) died. No significant differences were found in the number of patients who were admitted for HF between the group with positive scintigraphy and the group with negative scintigraphy (46.7% vs. 37.1%; p=0.529) (Tables 1 and 2).

In the survival analysis, patients with positive scintigraphy had a median time to admission of 5.2 months (confidence interval [CI] 95% 0–10.9), while for patients with negative scintigraphy, it was 12.2 months (95% CI 11.7–12.8); log rank: p=0.041 (Fig. 1). For the time to the combined endpoint (death and admission for HF), the patients with positive scintigraphy had a median time to the event of 1.9 months (95% CI 0–6.1), and the patients with negative scintigraphy had a median time to the event of 11.9 months (95% CI 11.7–12) (log-rank: p=0.027) (Fig. 2).

Age (odds ratio [OR] 1.17, 95% CI 1–1.37, p=0.039) and functional class (I–II vs. III–IV) (OR 4.7, 95% CI 1.05–20.99, p=0.042) were identified as factors associated with presentation with a positive scintigraphy result in our cohort of patients with HFpEF after adjusting for the rest of the factors involved. On the other hand, no association was found between the various comorbidities or the Charlson index and a greater probability of presenting with a positive result in the scintigraphy. In the analysis of the variables of the geriatric assessment and frailty, a trend of an association, which was confirmed in the univariate analysis, was found between presenting with a lower score on the Barthel Index and positive scintigraphy (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.94–1, p=0.065), which lost statistical significance after adjustment for age and functional class. The remainder of the variables (degree of frailty measured by Fried phenotype, SPPB, Lawton IADL Scale) were not found to be predictors of having a positive scintigraphy result (Table 3).

Factors associated with presenting ATTR-CA (positive scintigraphy).

| Variable | Univariant | Multivariant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age (years) | 1.24 (1.06–1.46) | 0.006 | 1.17 (1.00–1.37) | 0.039 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.44 (0.12–1.52) | 0.198 | ||

| Functional class (NYHA) | 0.030 | – | 0.664 | |

| I | 1 | – | ||

| II | 0.36 (0.04–3.14) | 0.361 | ||

| III | 3.50 (0.47–3.14) | 0.220 | ||

| IV | 5.25 (0.69–39.47) | 0.107 | ||

| NYHA (I–II vs. III–IV) | 7.94 (2.01–31.34) | 0.003 | 4.70 (1.05–20.99) | 0.042 |

| Hypertension | 0.78 (0.22–2.72) | 0.700 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 0.34 (0.03–3.15) | 0.346 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.84 (0.23–3.02) | 0.797 | ||

| Coronary heart disease | 0.55 (0.05–5.41) | 0.611 | ||

| Stroke | 1.93 (0.37–9.97) | 0.429 | ||

| Charlson index | 1.13 (0.78–1.64) | 0.489 | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.78 (0.22–2.72) | 0.700 | ||

| Frailty (Fried phenotype) | 0.648 | |||

| Robust | 1 | – | ||

| Pre-frail | 1.16 (0.16–8.09) | 0.876 | ||

| Frail | 1.96 (0.33–11.57) | 0.453 | ||

| Frailty (robust vs. pre-frail/frail) | 1.62 (0.29–8.92) | 0.576 | ||

| SPPB | 0.87 (0.74–1.03) | 0.116 | ||

| Lawton IADL Scale | 0.88 (0.72–1.07) | 0.202 | ||

| Barthel Index | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 0.065 | – | 0.868 |

SPPB: short physical performance battery; IADL: instrumental activities of daily living.

This study of the prevalence of ATTR-CA in the geriatric population is one of the first, in the literature, to describe parameters of functionality, frailty and geriatric syndromes, addressing a pathology that mainly affects elderly patients. Interest in this disease has grown exponentially in recent years, since it is estimated to be an important etiology in the spectrum of HFpEF. There are also several clinical trials underway with potentially promising treatment results. These treatments are associated with a high cost and would be indicated in the initial stages of the disease because they have shown greater effectiveness. Carrying out a detailed geriatric assessment would be indicated particularly in elderly patients, as this would allow the detection of patients who could benefit from this treatment compared to those likely to receive no benefit.19,20

In our cohort of patients with a history of HFpEF and echocardiographic signs of LV thickening and diastolic dysfunction, we found a 30% prevalence of ATTR-CA. Previous studies have estimated the prevalence of ATTR-CA in patients with HF diagnosed by imaging tests or biopsy to be between 5 and 20%.3,21,22 The prevalence observed in our study is significantly higher than that reported by González-Lopez et al.,3 in a sample of 120 patients admitted for HFpEF in a Spanish population, where a prevalence of 13% was described; the authors also used scintigraphy as the diagnostic method for suspected cases. This important difference could be because the mean age of our sample was significantly older (82 vs. 86 years), and this variable was shown to be associated with a greater probability of presenting with ATTR-CA in our study. We also found a lower prevalence, approximately 18%, in the study carried out by Sammer et al.,23 and the median age of their sample was 75 years, which was also much lower than ours.

Regarding general characteristics, our study population was a sample of elderly patients (mean age, 86 years) with significant associated comorbidities and a high prevalence of AF. These patients also present with geriatric syndromes, mainly dementia and a history of falls, and most of them presented with some degree of dependence in BADL, with a moderate or severe dependence in 48% of the sample. The incidence of frailty, according to the Fried phenotype, was 50%, with a median SPPB score of 6 points. These baseline characteristics are similar to those found in other population studies or clinical trials that included patients with HFpEF,24 including the higher prevalence of AF among the older patients in our study, which was similar to what was observed in a study by Tromp et al.25

When we tried to compare the prevalence of frailty (quantified using the Fried phenotype and the SPPB), no statistically significant difference was found when using the Fried phenotype, with prevalences between 45% and 60% in both groups (scintigraphy+ vs. scintigraphy−). However, when we used the SPPB, we found a tendency to present with a lower score in patients with a diagnosis of ATTR-CA. This suspicion, based on the results of our work, that patients with ATTR-CA could have a higher prevalence of frailty, was confirmed in a recently published study in a French population.26 With a sample size of 36 patients, the authors found a 50% prevalence of frailty measured by the Fried phenotype, slightly lower than that found in our study, which is estimated at 60%. This difference could be because our work included older patients and patients who were more dependent in BADL.

We found that advanced age and a worse functional class (NYHA III–IV) showed a statistically significant relationship with a higher probability of presenting with a positive result in the scintigraphy, which was maintained after adjusting for the rest of the factors involved. These findings are consistent with all the published literature, which insists on the idea that ATTR-CA is a cause of HF with an almost exclusive appearance in elderly patients and therefore should be ruled out when starting the assessment of all HF patients ≥65 years.27

Similarly, a highlighted study based on autopsies carried out in patients with HFpEF did not find amyloid deposition in any cardiac biopsy of patients under 65 years of age, finding an ATTRwt-CA prevalence of 40% in those over 80 years of age. Likewise, an advanced NYHA functional class, which indicates a greater probability of a diagnosis of HF, would lead to a greater suspicion of ATTR-CA and therefore to its diagnosis. On the other hand, the NYHA classification has been used as a variable in recently published prognostic classifications for the follow-up of cardiac amyloidosis (CA).28 After consulting the literature, we did not find other studies that analyzed factors associated with a greater probability of presenting with CA.

When we focused on the clinical results, we found a relationship in the survival analysis between the diagnosis of ATTR-CA (by compatible cardiac scintigraphy) and the increased risk of mortality and readmission at the one-year follow-up. In line with this result, in a study carried out in the United States, it was observed that in patients admitted for decompensation of heart failure, the presence of CA was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.17–1.82) and readmission at 30 days (OR 1.17, 95% CI 1.05–1.31).23 These results are consistent with the high morbidity and mortality associated with the presence of CA in other cohorts.29–31

ConclusionsATTR-CA appears to be a prevalent etiology in elderly patients in the spectrum of HFpEF. It is also associated with a high incidence of geriatric syndromes, frailty and dependence in BADL.

Patients with a diagnosis of ATTR-CA, established by a positive result in cardiac scintigraphy, had a shorter time to admission for HF and the combined event of death and admission compared to patients with a negative result in scintigraphy.

Advanced age and a poorer NYHA functional class were established as predictors of presenting with a positive result in cardiac scintigraphy in our study.

Study strengthsThis is the first study that aims to analyze the impact of ATTR-CA in the geriatric population, and this disease mainly affects elderly patients. These results also establish an analysis of the prevalence of frailty, functional impairment and other geriatric syndromes in patients with ATTR-CA compared to the rest of the patients in the spectrum of HFpEF. It would be necessary to expand the research in this field in future studies to try to draw statistically significant conclusions about the prognostic factors in this group of patients.

Study limitationsFirst, this is a single-center study, and therefore, a small sample was collected, which makes it difficult to draw statistically significant conclusions. Likewise, with regard to the diagnosis of ATTR-CA, our work was designed and carried out prior to the publication of the position document prepared by the European Society of Cardiology.32 This article establishes that to make the noninvasive diagnosis of ATTR-CA, in addition to cardiac scintigraphy with uptake grade 2 or 3 and compliance with echocardiographic criteria, it is necessary to rule out light chain amyloidosis (AL-CA). In our protocol, the analytical evaluation of discarding the monoclonal component was not carried out, in line with the diagnostic method used in previous publications.3

FundingThis work was partially supported by grants (to RA and JJ) from the “VIII Convocatoria Proyectos de Investigación Santander-UAX”, a resource of Universidad Alfonso X el Sabio, as part of registered Project 1.011.103.

Authors’ contributionsJavier Jaramillo Hidalgo: data acquisition and analysis, manuscript drafting, contribution to study design; Rocio Ayala-Muñoz, Maribel Quezada-Feijoó and Mónica Ramos: conceived and designed the study, data acquisition, contribution to manuscript drafting; Rocío Toro and Javier Gómez-Pavón: significant intellectual contribution to manuscript drafting.

Ethical approvalAll procedures were performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinky. The study protocol was approved by the UAX Biomedical Research Ethics committee.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.