Symptom control at the end of life is essential, and palliative sedation is a viable intervention option for the care of terminally ill patients. This study aims to characterize the elderly population receiving end-of-life care plans and their management with palliative sedation in a geriatric unit at a high complexity hospital.

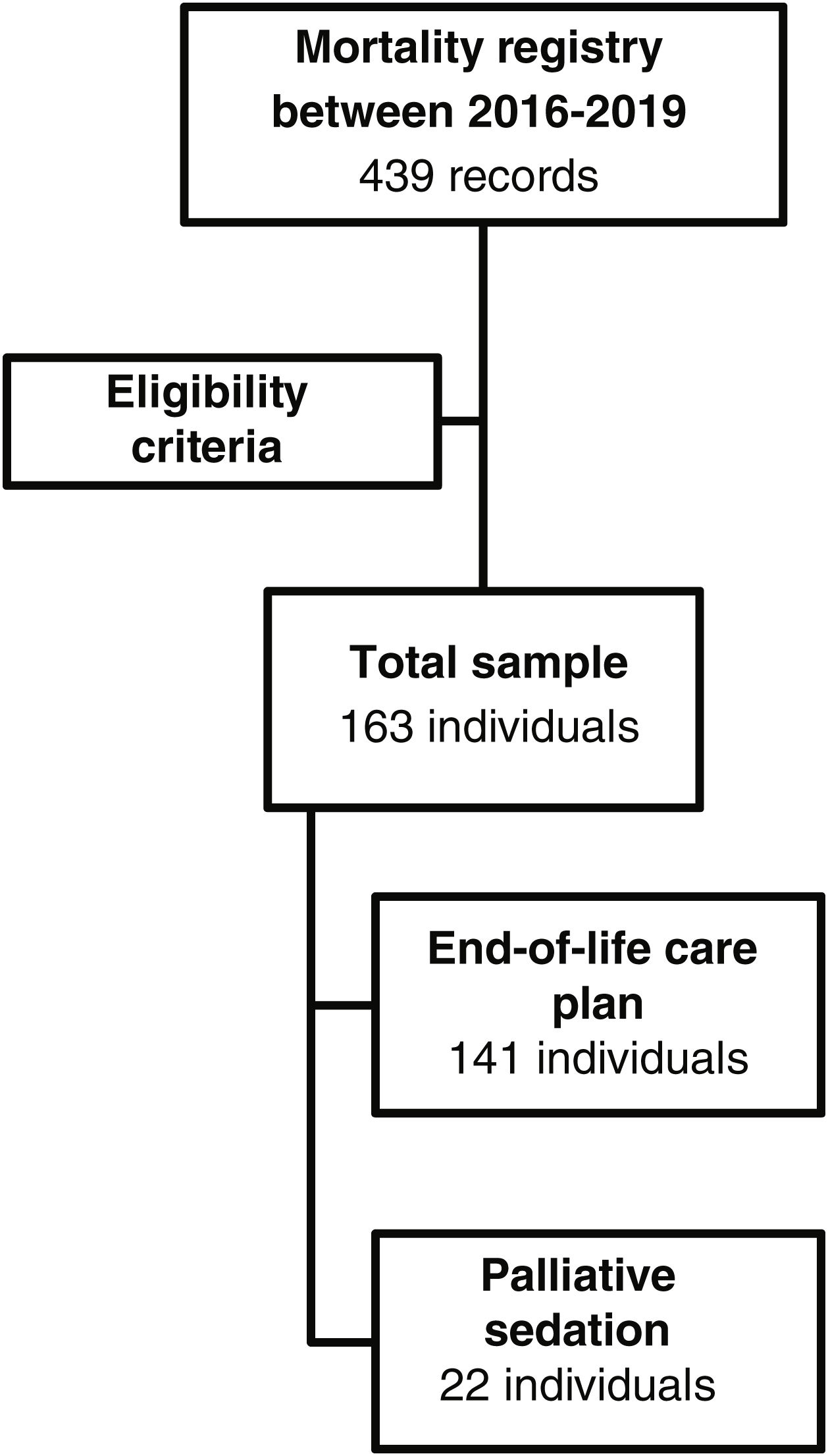

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted, and a descriptive analysis was performed. Medical records of 163 patients admitted to a high complexity hospital in Bogota, Colombia between January 2016 and December 2019 were reviewed.

ResultsFrom 163, 141 patients received an end-of-life care plan, and 22 were managed with palliative sedation. The mean age was 84 years, the most frequent cause of death was respiratory infections and 44% of patients had a history of cancer. Prior to admission, functional decline and the presence of moderate to severe dementia were frequently found. About one in ten persons required palliative sedation, which lasted an average of 2.22±5 days. The most common refractory symptom was dyspnea (45.45%), followed by pain (36.36%).

ConclusionsPalliative sedation is prevalent in the elderly population and characterizing this population can provide increased knowledge to improve end-of-life care.

El control de síntomas al final de la vida es fundamental, y la sedación paliativa resulta una opción de intervención en el cuidado de pacientes con enfermedades terminales. El objetivo es caracterizar una población de personas mayores que recibieron un plan de atención del final de la vida, incluyendo sedación paliativa en una unidad de geriatría de un hospital de alta complejidad.

Materiales y métodosEstudio de corte transversal, se realizaron análisis descriptivos y se utilizaron métodos de acuerdo con el tipo de variable. Se revisaron las historias clínicas de 163 pacientes entre enero de 2016 y diciembre de 2019 de un hospital de alta complejidad en Bogotá, Colombia.

ResultadosSobre 163 pacientes, 141 recibieron plan de atención de final de vida y 22 fueron manejados con sedación paliativa. La edad promedio fue de 84 años y el 58% eran mujeres. La causa de muerte más frecuente fue respiratoria infecciosa; el 44% tenían antecedente oncológico. La declinación funcional previa al ingreso y la presencia de demencia moderada o severa fueron condiciones que frecuentemente se encontraron en quienes se reorientó el esfuerzo terapéutico. Una de cada 10 personas requirió sedación paliativa, cuya duración fue de 2,22±5 días, el síntoma refractario más frecuente fue la disnea (45,45%), seguido de dolor (36,36%).

ConclusionesLa sedación paliativa resulta frecuente en la población mayor con enfermedades no oncológicas. La caracterización de estas personas promueve el aumento del conocimiento y la preparación para mejorar el manejo del final de la vida.

With the demographic transition phenomenon, the elderly population is on the rise and with it, chronic non-transmissible diseases, including cancer and dementia. Many of these diseases have no curative possibility; however, they require adequate symptom control in the quest to ensure the patient's quality of life. In scenarios where the curative possibilities have been exhausted and the pathology leads to symptoms and suffering, palliative care appears as a fundamental axis in the accompaniment and relief of pain and distress.1 For this reason, in recent years the development of strategies and training in palliative care has been promoted worldwide in an attempt to guarantee a good death.1,2

At the end of life, different palliative options have been proposed that seek to alleviate suffering in the physical, cognitive, emotional and behavioral spheres, such as the development of an end-of-life care plan and palliative sedation (PS), a process that must be individualized. The end-of-life care plan should be understood as the set of interventions put in place when reorientation on both the therapeutic effort and the objectives are focused on ensuring symptom control and comfort.3 Palliative sedation is a relatively new concept, which is defined as an intervention that seeks to reduce the state of consciousness with drugs to relieve refractory symptoms in spite of an optimal medical management. Therefore, its aim differs from euthanasia whose main purpose is to shorten the time of life. The worldwide prevalence varies between 2 and 52% depending on the setting, research methodology and definition.4 Among the most frequently described refractory symptoms are delirium, incoercible pain and dyspnea.5

The hospital is one of the stages where the elderly typically die due to the complexity of their diseases, the resources they require and the availability of health personnel to alleviate the symptoms at the end of life. Colombia decrees since 2014 with Law 1733,6 the right of people facing terminal, chronic, degenerative and irreversible diseases, to be recipients of palliative care, to receive comprehensive therapeutic interventions for pain, relief of suffering and other symptoms, including the regularization of palliative sedation to improve their quality of life and that of their families taking into account the relevant psychopathological, physical, emotional, social and spiritual aspects.

Studies aiming to characterize the causes of death and end-of-life management allow to acquire knowledge and compare the findings among different institutions in order to consider modifications on indications, therapy, completion and follow-up of the end-of-life care plan and palliative sedation. Researches have been carried out nationwide, some of which evaluate the end-of-life decision-making process through questionnaires7 and by means of an ethnographic approach.8

The goal of this study is to characterize the population of elderly people who received end-of-life care plans and/or palliative sedation in the geriatric unit of a fourth level hospital in Bogota, Colombia to promote the knowledge of palliative sedation as possible intervention and to improve the design of a multidimensional and interdisciplinary management plan for the patient and his family in the end-of-life care.

MethodologyThis is an observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study. A total of 439 medical records of patients who died in the Geriatrics Unit of the Hospital Universitario San Ignacio, a fourth level institution located in Bogota, Colombia, between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2019, whose process included the implementation of end-of-life patient care plan and/or the institutional palliative sedation protocol, were reviewed.3 A database was constructed in which the variables of interest to be analyzed were recorded and registered in RedCap (electronic data capture software for designing databases on research), we included patients who had Barthel at hospital admission.

The end-of-life care plan refers to as a construction of measures and interventions that are carried out when redirection of the therapeutic effort to ensure symptom control and patient comfort is considered.3 In our institution, in recent years this plan has been structured, which consists of transferring the terminally ill patient in his or her last hours of life to a more intimate environment, allowing visits free of schedule, suspending the usual vital signs taking and glucometry, promoting the control of symptoms that the patient presents at this moment of life with medications or therapies if required. In addition, it's included skin hydration, scheduled changes of position, spiritual support for the patient and family, permanent contact with the medical team to clarify doubts and advice and assessment by the hospital's clinical ethics team if needed.

On the other hand, palliative sedation is a therapeutic intervention to lighten the burden of refractory symptoms treatment caused by a given pathology at the end of life. A symptom is considered refractory when all possible treatments available have been tried within a time frame, with optimal doses and a risk–benefit ratio, but have not been successful.9

In the present study, patients were included in the mortality registry of the Geriatrics Service of the Hospital Universitario San Ignacio. Exclusion criteria included the absence of data on the Barthel Index scale at admission, and those whose clinical history did not clearly record the presence of refractory symptoms to opt for being recipients of palliative sedation. Demographic variables included age and sex, and clinical variables included length of hospital stay, cause of death, number of comorbidities and the presence of oncologic disease. In the baseline situation, the Mininutritional Assessment Abbreviated (MNA-SF) was used as a continuous variable10 with cut-off points greater than or equal to 12 when considering adequate nutritional status; greater than 7 and less than 12 meaning risk of malnutrition and less than or equal to 7, malnutrition; functionality was measured using the Barthel Index,11 so that independence was considered a result equal to or greater than 90, mild dependence from 60 to 85, moderate dependence from 40 to 55, severe dependence from 20 to 35 and total dependence understood as a score of less than 20. Functional decline was defined as the loss of 5 or more points on the Barthel Index compared to functionality at least 15 days prior to admission.12 In the mental domain, data from the clinical history, a clear history of major neurocognitive disorder and in those who did not have an established baseline situation, the information from the Folstein Minimental Scale (MMSE) was applied within the stay, with scores greater than or equal to 27 being considered as not cognitively impaired.13–15 In order to classify dementia stage and commitment, we used the correlation with the score obtained in the Minimental and the functional compromise related to neurocognitive disorder using data from the Barthel Index at admission. In the social field, a semi-structured interview was conducted to inquire on whether social support was present or not.16 In those who received palliative sedation, the time of sedation, type of medications used, refractory symptoms, vital signs, support from the palliative care team and spiritual service, among other aspects, were also determined.

The data and the correlation between the variables were analyzed using Excel and the statistical analysis software Stata 14. The variables, taken from the information recorded in the questionnaires, were coded into categorical and numerical according to the nature of the variable to be analyzed. Within the categorical variables, measures of central tendency were used to analyze the data collected. Implementation of absolute frequencies and mode were used for general and subgroups analysis. For numerical variables, averages and standard deviations were useful to describe the sample and numerical analysis. No normality test was performed, since the extreme values were taken into account due to the objectives and descriptive nature of the work. Subsequently, to evaluate the difference between the groups of participants according to the type of variable, the T-Student or Chi-square test was used.

The Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitario San Ignacio and the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana approved the study by number 2019/05.

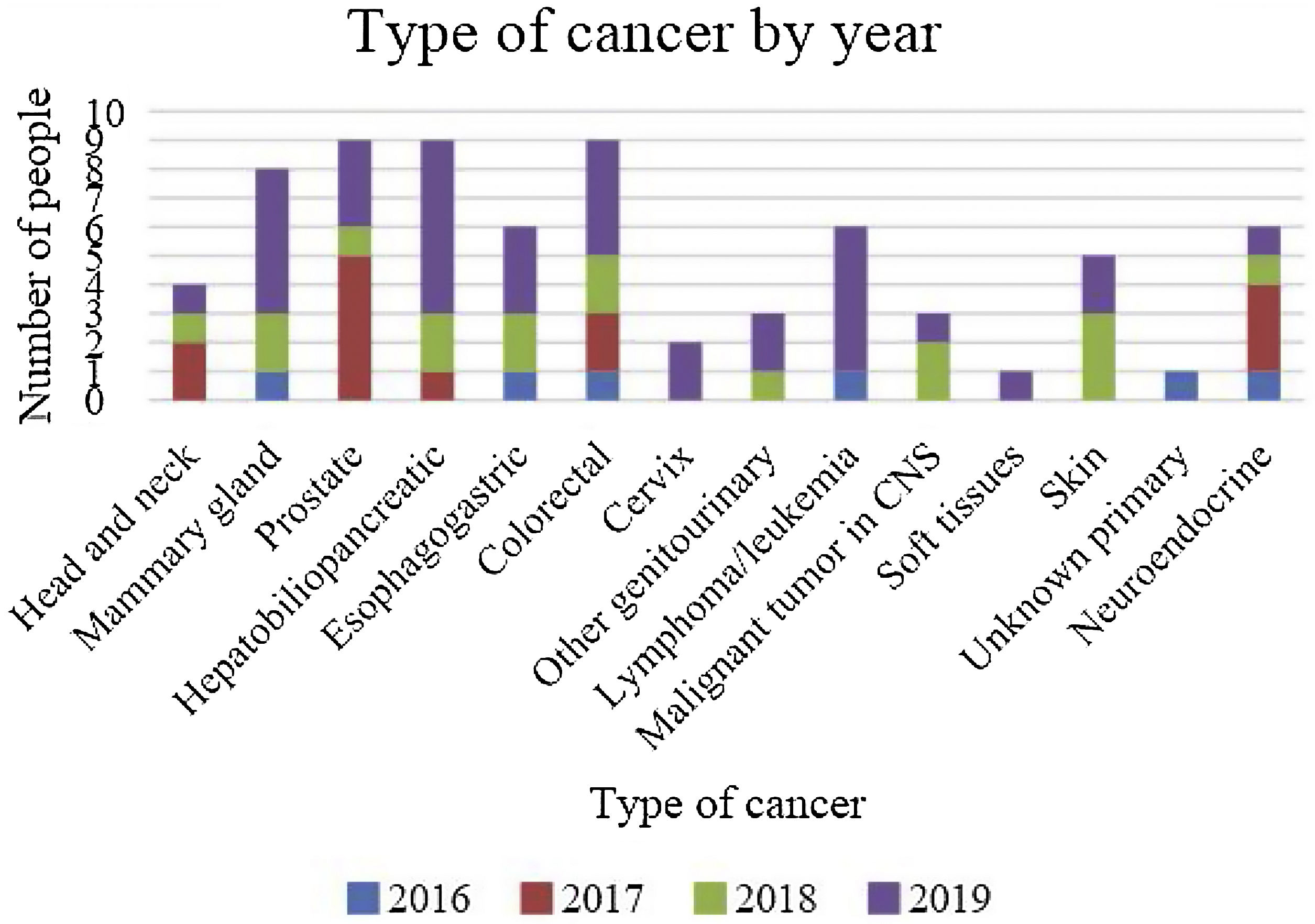

ResultsAfter the reviewing of 439 records in the mortality database, 163 met eligibility criteria: 141 under the end-of-life care plan and 22 received end-of-life and palliative sedation (Fig. 1). The average age was 84.7±5.84 years, the majority were women (58.9%), inpatient stay span was 9.84 days; among the most frequent causes of death were infectious diseases of the respiratory system, followed by non-infectious genotourinary system diseases, and then, non-infectious diseases of the respiratory system, with an average of 5.15 comorbidities; 44% had oncological conditions, of which 62.5% were of an advanced stage (Fig. 2 shows the distribution of the type of cancer by year).

Comparison over the different yearsIn terms of clinical characteristics, the age of the deceased persons analyzed is similar throughout the different years, with a tendency to be older over time; female sex continues to prevail over the years. The length of stay was shorter in 2018, and 2017 was the year with the lowest number of comorbidities.

The likelihood of institutionalization prior to admission in each year is low, being higher in 2016, most of them have adequate social support on an on-going basis.

This geriatric unit had 402 admissions in 2016, 727 in 2017, 1831 in 2018 and 2171 patients’ admissions in 2019. This progressive rise in admissions was related to the increased hospitalization capacity through the hiring of geriatricians.

Baseline situationThe abbreviated nutritional assessment short form (MNS-SFA) yielded an average score of 10.27 in the malnutrition risk range. At the functional level, 25.76% had mild dependence followed by 22.69% with total dependence for basic activities of daily living. When analyzing the Barthel Index at admission, the average was 30 points (severe dependence), and 44.8% had functional decline prior to admission. In the mental realm, 23.31% presented major neurocognitive disorder in severe stage and 29.44% in moderate stage. In the social field, 12.27% had previous institutionalization and 90.8% had social support at that time (at least one caregiver) (more information in Table 1).

General characteristics of the population that received end-of-life care plan.

| Variables | Years | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 n=16 | 2017 n=37 | 2018 n=41 | 2019 n=69 | 2016–2019n=163 | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 82.56 (5.64) | 83.18 (6.81) | 85.13 (5.69) | 85.72 (5.15) | 84.7 (5.84) |

| Woman, n (%) | 8 (50%) | 19 (51.30%) | 27 (65.80%) | 42 (60.90%) | 96 (58.9%) |

| Length of hospital stay (days, SD) | 10 (6.78) | 10.76% (9.29) | 8.14 (5.56) | 10.32 (12.1) | 9.84 (9.73) |

| Cause of death, n (%) | |||||

| Infectious in respiratory system | 47 (28.83%) | ||||

| Non-infectious in genitourinary system | 32 (19.63%) | ||||

| Non-infectious in respiratory system | 20 (12.27%) | ||||

| Infectious in the nervous system | 17 (10.43%) | ||||

| Infectious in cardiovascular system | 15 (9.20%) | ||||

| Non-infectious in the nervous system | 9 (5.52%) | ||||

| Non-infectious in cardiovascular system | 7 (4.29%) | ||||

| Number of comorbidities (mean, SD) | 5.31 (2.87) | 4.6 (1.58) | 5.1 (1.77) | 5.1 (1.95) | 5.15 (2.03) |

| Presence of oncologic disease, n (%) | 6 (37.5%) | 13 (35%) | 17 (41%) | 36 (53%) | 72 (44.17%) |

| Located | 3 (50%) | 6 (46%) | 7 (41%) | 11 (31%) | 27 (37.5%) |

| Metastatic | 3 (50%) | 7 (54%) | 10 (59%) | 25 (69%) | 45 (62.5%) |

| Baseline situation | |||||

| Nutritional status | |||||

| MNA-SF (mean, SD) | 12.5 (5.4) | 12.9 (6.3) | 12.3 (5) | 7.15 (4.14) | 10.27 (5.72) |

| Functionality | |||||

| Previous BADL functionality (mean, SD) | 40 (30) | 55 (36) | 45 (34) | 53 (33) | 50 (34) |

| Independent, n (%) | 2 (12.50%) | 8 (21.62%) | 9 (21.95%) | 16 (23.18%) | 35 (21.47%) |

| Mild dependence, n (%) | 3 (18.75%) | 12 (32.43%) | 9 (21.95%) | 18 (26.08%) | 42 (25.76%) |

| Moderate dependence, n (%) | 3 (18.75%) | 5 (13.51%) | 6 (14.63%) | 9 (13.04%) | 23 (14.11%) |

| Severe dependence, n (%) | 3 (18.75%) | 3 (8.10%) | 5 (12.20%) | 15 (21.73%) | 26 (15.95%) |

| Total dependence, n (%) | 5 (31.25%) | 9 (24.32%) | 12 (29.26%) | 11 (15.94%) | 37 (22.69%) |

| Functionality at admission BADL (mean, SD) | 28 (28) | 35 (37) | 25 (31) | 37 (34) | 33 (34) |

| Functional decline (n, %) | 8 (50%) | 17 (46%) | 21 (51.2%) | 27 (39.1%) | 73 (44.8%) |

| Percentage of functional decline | 39.2% | 41.1% | 49.8% | 30.58% | 38.34% |

| Mental | |||||

| No cognitive impairment | 1 (6.25%) | 5 (13.51%) | 5 (12.19%) | 11 (15.94%) | 22 (13.49%) |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 1 (6.25%) | 6 (16.21%) | 5 (12.19%) | 11 (15.94%) | 23 (14.11%) |

| Mild MND | 1 (6.25%) | 8 (21.62%) | 9 (21.95%) | 14 (20.29%) | 32 (19.63%) |

| Moderate MND | 7 (43.75%) | 7 (18.91%) | 14 (34.14%) | 20 (28.98%) | 48 (29.44%) |

| Severe MND | 6 (37.5%) | 11 (29.72%) | 8 (19.51%) | 13 (18.84%) | 38 (23.31%) |

| Social | |||||

| Institutionalization prior to admission, n (%) | 4 (25%) | 2 (5.4%) | 5 (12.2%) | 9 (13%) | 20 (12.27) |

| Adequate ongoing social support, n (%) | 15 (93.75%) | 33 (89.19%) | 38 (92.68%) | 62 (89.85%) | 148 (90.80%) |

SD: standard deviation; BADL: basic activities of daily living; MND: major neurocognitive disorder. Percentage of functional decline ((previous Barthel Index−Barthel Index at admission/previous Barthel Index)×100); MNA-SF: Mininutritional Assessment Short Form.

Dyspnea was the most frequent symptom (60.99%), followed by pain (45.39%), terminal delirium (19.14%) and terminal anxiety (9.92%). Dyspnea in 97.67% of the cases was managed with opioids; with respect to pain, 45.39% were also managed with opioids, hydromorphone being the first option, taking into account that 28.12% were naive to this type of medication. Terminal delirium was treated in all cases with haloperidol and terminal anxiety was managed in 92.85% with this same medication (more characteristics in Table 2). Vital signs were recorded in 72% of the histories during the end-of-life care plan, and glucometry in 12.05%. Regarding interdisciplinary interventions, 47.51% received assistance from palliative care, 31.20% were accompanied by spiritual services and 34.04% of the cases were evaluated by the institution's ethics committee (more information in Table 2).

Characterization of end-of-life management between 2016 and 2019, n=141.

| End-of-life management | |

|---|---|

| Variables | n (%) |

| Hydration with intravenous or subcutaneous fluids | 137 (97.16) |

| Symptom management | |

| Dyspnea | 86 (60.99) |

| Opioid | 84 (97.67) |

| Pain | 64 (45.39) |

| Opioid | 64 (45.39) |

| Hydromorphone | 30 (46.87) |

| Morphine | 20 (31.25) |

| Other analgesic | 23 (35.93) |

| Naive on opioid | 18 (28.12) |

| Constipation (management with lactulose) | 4 (2.83) |

| Urinary retention | 7 (4.96) |

| Terminal anxiety | 14 (9.92) |

| Haloperidol | 13 (92.85) |

| Terminal delirium (management with haloperidol) | 27 (19.14) |

| Registration of vital signs | 102 (72.34) |

| Blood glucose recordings | 17 (12.05) |

| Interdisciplinary management | |

| Palliative care accompaniment | 67 (47.51) |

| Accompaniment by spiritual service | 44 (31.20) |

| Ethics committee assessment | 48 (34.04) |

The sample who received end-of-life and palliative sedation (Table 3), had an average age 80.7 years, being more frequent in men (59%), and 40% were functionally dependent; at the mental level, there was a greater presence of major neurocognitive disorder in severe stage (27.27%). The most frequent cause of death was infectious respiratory disease (27.27%), followed by oncologic disease (22.72%) and then sepsis of non-respiratory origin (13.63%). The mean number of comorbidities was 5.31, the length of hospital stay was 10.68±8.39 days and the time from admission to the start of sedation varied between 1 and 15 days. On the characteristics of sedation, the length of time was 2.22±5 days, the most frequent refractory symptom was dyspnea (45.45%) followed by pain (36.36%) and agitation (13.63%).

Characterization of people who received palliative sedation management between 2016 and 2019, n=22.

| Variables | n (%) or mean±SD |

|---|---|

| Age – years (SD) | 80.7±12 |

| Man | 13 (59) |

| Functionality (BADL) | |

| Independent | 3 (13.63) |

| Mild dependence | 8 (36.36) |

| Moderate dependence | 2 (9.09) |

| Severe dependence | 1 (4.54) |

| Total dependence | 9 (40.90) |

| Major neurocognitive disorder | 17 (77.27) |

| Severe | 6 (27.27) |

| Moderate | 4 (18.18) |

| Mild | 4 18.18) |

| Cause of death | |

| Infectious respiratory disease | 6 (27.27) |

| Oncologic disease | 5 (22.72) |

| Sepsis other than respiratory | 3 (13.63) |

| Non-infectious respiratory disease | 3 (13.63) |

| Number of comorbidities (DE) | 5.31±3.8 |

| Length of hospital stay (Days SD) | 10.68±8.39 |

| Sedation time (days SD) | 2.22±5 |

| Time from admission and start of sedation | 8.45±7.71 |

| Refractory symptom that indicated sedation onset | |

| Dyspnea | 10 (45.45) |

| Pain | 8 (36.36) |

| Agitation | 3 (13.63) |

| Other (massive hemorrhage, nausea and uncontrollable vomiting) | 1 (4.54) |

| Interdisciplinary team | |

| Co-management with palliative care | 15 (68.18) |

| Service initiating sedation (palliative care) | 13 (59.09) |

| Ethics committee assessment | 5 (22.72) |

| Accompaniment by spiritual service | 7 (31.81) |

| Pharmacological and non-pharmacological management | |

| Hydration with intravenous fluid | 22 (100) |

| Benzodiazepine use (midazolam) | 22 (100) |

| Opioid use | 22 (100) |

| Hydromorphone | 18 (81.81) |

| Morphine | 3 (13.63) |

| Oxycodone | 1 (4.54) |

| Use of antipsychotic (haloperidol) | 11 (50) |

SD: standard deviation; BADL: basic activities of daily living.

Concerning interdisciplinary management, 68% received additional support from palliative care, among which 59% initiated palliative sedation. Likewise, 23% received assessment by the ethics committee and 31% support from the spiritual service. With regard to pharmacological and non-pharmacological aspects, in all cases hydration was by intravenous fluids, and they received treatment with benzodiazepines and opioids. The most frequently used opioid was hydromorphone (81.81%) and 50% were given haloperidol for delirium complementary management.

Additionally, the causes of death in this subgroup were principally related to infectious in respiratory system (31.81%), non-infectious in genitourinary system (18.18%), non-infectious in respiratory system (13.63%) and infectious in the nervous system (13.63%).

Comparison of end-of-life care plan versus palliative sedationTable 4 shows the demographic and baseline characteristics of those who received end-of-life care plan management and those who received palliative sedation, finding a statistically significant difference only in age, being lower in those who received palliative sedation.

Clinical characteristics of persons who received end-of-life plan versus palliative sedation.

| Variables | End-of-life care plann=141 | Palliative sedationn=22 | Value of p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age – years, mean±SD | 85.21±5.65 | 81.27±6.15 | <0.05 |

| Female, n (%) | 87 (61.70) | 9 (40.91) | 0.06 |

| Previous Barthel Index, mean±SD | 51.66±33.86 | 42.5±37.47 | 0.12 |

| Barthel Index admission, mean±SD | 33.22±33.83 | 29.09±37.40 | 0.29 |

| Functional decline, n (%) | 66 (46.81) | 7 (31.82) | 0.18 |

| Neurocognitive disorder, n (%) | 122 (86.52) | 19 (86.36) | 0.98 |

| MNA-SF, mean±SD | 9.79±5.61 | 13.36±5.72 | 0.99 |

| Social support present, n (%) | 128 (90.78) | 20 (90.01) | 0.98 |

SD: standard deviation.

This study highlights the importance of interdisciplinary management at the end of life. We found that most of the persons who died during the years evaluated were women, with functional decline prior to hospitalization, malnutrition, and major neurocognitive disorder from moderate to severe stages. It was also observed that over the years, the ethics committee and the spiritual service intervened more frequently, accompanying both the patient and the family, following strict hospital instructions and protocolized management through institutional guidelines on palliative sedation, and greater teamwork with the palliative care service.

As for the causes of death, pulmonary disease of infectious origin was the main factor in both those who received end-of-life care plans and those who received palliative sedation, representing the fifth leading cause of death in the city according to age group, and the sixth nationwide level for all age groups.17

The prevalence of palliative sedation was 13.5%, a figure lower than that reported in the literature, ranging between 51 and 64% in different studies,5,18,19 which could be due to the type of population evaluated and study settings, knowing that most were oncology patients in palliative care centers, quite different from our study since it was conducted in a high complexity hospital where the oncological background was 44%.

The characteristics of those who received palliative sedation are comparable to those described in other studies5,18,19; there is similarity in the prevalence of refractory symptoms, which in our case was dyspnea,5,18 possibly because respiratory disease was related to the main cause of death; in other studies, delirium was also relevant as a refractory symptom.18,19 According to national and international guidelines, there has been an adequate pharmacological management5,20–22 making first line use of benzodiazepine, and additionally opioids to optimize pain and dyspnea control. In this study, hydromorphone was the opioid more frequently reported, possibly because of the presence of contraindications to receive morphine due to our aged population and comorbidities. There is a discrepancy when compared to some guidelines having to do with the administration of antipsychotics, who recommend levomepromazine, which in our country is not frequently used in palliative sedation due to its unavailability for subcutaneous or intravenous use,21,22 being this the reason in our study for the majority of participants to receive haloperidol.

We recognize that among the limitations is that we had difficulty in defining the cause of death in specific cases based on the mortality record database from the geriatric unit, but we confirmed the causes of death from medical records information; also, the sample size of the population evaluated was small due to incomplete data of medical records, and the palliative sedation subgroup was also small; in addition, it is a cross-sectional study so causality cannot be determined. However, it represents the exposure of the clinical work done in the years prior to the pandemic by COVID-19, it stimulates the awareness of health personnel on the possibility of using palliative sedation in their patients, and promotes new research studies to make comparisons in clinical profile, cause of death and prevalence of an end-of-life care plan and palliative sedation in a context of limited resources during the pandemic.

Among the strengths, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first descriptive study of these characteristics in elderly people, including their baseline situation and management with palliative sedation by an interdisciplinary team. Additionally, it contributes to the knowledge on the subject at national and international level, suggests clinical conditions related to the instauration of palliative sedation, promotes the knowledge of this intervention and allows making contributions in the design of clinical practice guidelines on end-of-life palliative care, as well as multidimensional and interdisciplinary management plans for the patient and his family not only in the hospital setting but also at other existing levels of care (and even to promote the building of non-existing ones) whose teams are devoted to ensure the best conditions by the time of passing away including scenarios such as the home and geriatric facilities.

ConclusionsPre-admission functional decline and the presence of moderate to severe major neurocognitive impairment were clinical conditions being present in persons receiving end-of-life care plan. We found that 1 out of 10 people in the study required palliative sedation and the most frequent refractory symptom was dyspnea, followed by pain. There is a need of more studies assessing end-of-life care plan to build in every institution and other existing levels of care, a multidimensional and interdisciplinary management based on patients’ wishes and patients and caregivers’ needs.

Sources of fundingThe authors state that they did not require funding for the completion of this work.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no affiliation or involvement with any organization with commercial or financial interest into what is discussed in this manuscript.