We aim to conduct a systematic review of the literature to evaluate the effectiveness of artificial intelligence prediction models in predicting complications in adult patients undergoing surgery for degenerative thoracolumbar pathology compared with other commonly used prediction techniques.

MethodsA systematic literature review was conducted in Medline/Pubmed, Cochrane Library, and Lilacs/Portal de la BVS to identify machine learning models in predicting complications in patients undergoing surgery for degenerative thoracolumbar spine pathology between January 1, 2000, and May 1, 2023. The risk of bias was assessed using the PROBAST tool. Study characteristics and outcomes focusing on general or specific complications were recorded.

ResultsA total of 2341 titles were identified (763 were duplicates). Screening was performed on 1578 titles, and 22 were selected for full-text reading, with 18 exclusions and 4 publications selected for the subsequent review. Additionally, 8 publications were included from other sources (Argentine Association of Orthopaedics and Traumatology Library; manual citation search). In 5 (41.6%) articles, the effectiveness of artificial intelligence predictive models was compared with conventional techniques. All were globally classified as having a very high risk of bias. Due to heterogeneity in samples, outcomes of interest, and algorithm evaluation metrics, a meta-analysis was not performed.

ConclusionAlthough the available evidence is limited and carries a high risk of bias, the studies analysed suggest that these models may achieve promising performance in predicting complications, with area under the curve values mostly ranging from acceptable to excellent.

El objetivo de los autores es realizar una revisión sistemática de la bibliografía para evaluar la efectividad de los modelos predictivos de inteligencia artificial en la predicción de complicaciones en pacientes adultos tratados mediante cirugía por enfermedad toracolumbar degenerativa, en comparación con otras técnicas predictivas de uso habitual.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó una revisión sistemática de la bibliografía en Medline/Pubmed, Cochrane Library y Lilacs/Portal de la BVS sobre la efectividad del uso de modelos predictivos de inteligencia artificial para las posibles complicaciones en pacientes operados por enfermedad degenerativa de la columna toracolumbar durante el periodo de 1 de enero de 2000 y 1 de mayo de 2023. El riesgo de sesgo se evaluó con las herramientas ROBINS-I y PROBAST. Se registraron características de los estudios y resultados, contemplando como desenlace complicaciones generales o específicas.

ResultadosSe identificaron 2.321 títulos, 763 eran duplicados. Se realizó el cribado de 1.558 títulos; 22 fueron elegidos para su lectura completa con exclusión de 18 y elección final de 4 publicaciones para la siguiente revisión. Adicionalmente, se incluyeron 8 publicaciones desde otras fuentes (Biblioteca Asociación Argentina de Ortopedia y Traumatología, con búsqueda manual de citas). En 5 artículos (41,6%) se compararon la efectividad de modelos predictivos de inteligencia artificial frente a técnicas habituales. Todos fueron catalogados globalmente con muy alto riesgo de sesgo. Dada la heterogeneidad de las muestras, los resultados de interés y las métricas de evaluación de los algoritmos, no se realizó un metaanálisis.

ConclusiónSi bien la evidencia disponible es limitada y presenta un alto riesgo de sesgo, los estudios analizados indican que estos modelos pueden alcanzar un desempeño prometedor en la predicción de complicaciones, con valores del área bajo la curva que, en su mayoría, oscilan entre aceptables y excelentes.

According to U.S. statistics, the estimated cost of degenerative vertebral disease is around $100 billion annually.1 It is estimated that 2 out of 3 adults will experience low back pain at some point in their lives.2 The complexity of patients with spinal disease and the complications associated with surgery have motivated research into strategies for accurate prediction of these episodes, as well as the anticipated estimate of clinical outcomes. Traditionally, different models of statistical analysis have made it possible to identify predicative factors for complications, with great popularity enjoyed by multivariate analysis models, such as logistic regression, which produces a measurement of risk (odds ratio) for independent variables on a specific effect or outcome.3

The field of artificial intelligence (AI) has had a significant impact on multiple areas of health care, and spinal surgery is no exception.3,4 AI is concerned not only with understanding but also with building “intelligent entities”: machines that can calculate how to act effectively and safely.4 AI comprises a variety of disciplines including: natural language processing, knowledge representation, automated reasoning, machine learning (ML), and robotics. ML is a subarea that enables the system to learn and provide feedback to itself; that is, to develop algorithms that improve with experience. ML involves numerous methods, such as deep learning, based on artificial neural networks.3,4 ML has also made it possible to develop predictive models, and in the last decade numerous articles have been published for their application in specific areas, such as spinal surgery.3,4

The authors aimed to conduct a systematic review of the literature to assess the effectiveness of predictive artificial intelligence models in predicting complications in adult patients treated with surgery for degenerative thoracolumbar disease, compared to other commonly used predictive techniques.

Materials and methodsA systematic review of the literature in the main biomedical databases (Medline/Pubmed, Cochrane Library and Lilacs/VHL Portal) was carried out on the effectiveness of the use of predictive AI models to predict complications in patients operated on for degenerative disease of the thoracolumbar spine during the period between the 1st of January 2000 and the 1st of May 2023.

Eligibility criteriaStudies were selected according to the following eligibility criteria:

Study designs: randomised, controlled clinical trials, prospective non-randomised studies, prospective and retrospective cohort observational studies, cross-sectional studies, and descriptive series with more than 10 cases. Case reports, reviews (systematic, narrative), editorials, letters to the editor, and consensus documents were excluded.

Participants: adult patients (18–65 years) of both sexes, treated for degenerative disease of the thoracolumbar spine (herniated disc, narrow lumbar canal, and adult, sagittal, or coronal deformity). Population studies with idiopathic, neuromuscular, congenital or syndromic scoliosis, osteoporosis/metabolic disease fractures, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis/diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, vertebral oncological disease, and studies on patients treated with blocking as a single treatment procedure (with no surgery) were excluded.

Intervention: use of AI for the creation of predictive models of complications, considering deep learning, machine learning, artificial neural networks, and other novel methods whose development involves the use of artificial intelligence. We excluded studies that used AI models for purposes other than complication prediction, such as patient and imaging assessment, classification, application in navigated surgery, or robotics.

Comparator: other common methods for predicting complications such as statistical methods or scales. Due to the novelty of the topic, studies without a comparator were also considered.

Outcomes: studies that recorded complications in surgical patients due to degenerative thoracolumbar disease, mainly covering intraoperative and early postoperative complications (90 days after surgery). Secondarily, complications over longer periods (6 months, 1 and 2 years) and other outcome variables, such as pain, functional disability, length of hospitalisation, readmissions, and morbidity and mortality.

Time: studies with follow-up time greater than or equal to 90 days.

Language: studies in English, Spanish and Portuguese.

Table 1 summarises the research question according to the PICO model, which enabled us to provide structure for the scientific problem, describing the eligibility criteria and guiding the bibliographical search.

Research question according to PICO model.

| PICO | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Surgically treated adult patients (aged 18–65 years) of both sexes with degenerative thoracolumbar spine conditions, including herniated disc, lumbar stenosis, and adult spinal deformity (sagittal and/or coronal). | Conditions such as idiopathic, neuromuscular, congenital or syndromic scoliosis, fractures caused by osteoporosis/metabolic disease, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis/hyperostosis, diffuse idiopathic skeletal (DISH) disease, spinal oncological conditions, patients who underwent blocking as a sole therapeutic procedure (with no surgery). |

| Intervention | The use of artificial intelligence in developing predictive models for complications. We took into account methods such as deep learning, machine learning, artificial neural networks, and other new approaches that involve artificial intelligence. | Studies that used artificial intelligence models for purposes other than prediction of complications were excluded. |

| Comparison | Other frequently used methods to predict complications, such as statistical models or measurement scales, were also considered. Due to the newness of the topic, studies without a comparison group were also included in the analysis. | |

| Outcome | Studies reporting complications, with a focus on intraoperative and early postoperative complications (within 90 days of surgery). Furthermore, we examined complications beyond the 90-day period, up to 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years. We also considered specific complications. | No complications were recorded. |

| Time | Studies with a follow-up period of 90 days or longer. | |

| Study design | Controlled randomised clinical trials (RCTs), prospective non-randomised studies, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and descriptive series with over 10 cases.Language: English, Spanish, and Portuguese. | Case reports, systematic and narrative reviews, editorials, letters to the editor, and consensus papers were excluded. |

PICO: P=patient; I=intervention; C=comparator; O=outcome.

A bibliographical search strategy was developed using the MEDLINE, Cochrane and LILACS databases (Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences) through the Pubmed and Cochrane Library search engines and the Virtual Health Library (VHL) portal. In addition, other sources of bibliographical citations were considered, such as consulting the library of the Argentine Association of Orthopaedics and Traumatology and manually searching the reference lists of the studies included or reviews (narrative/systematic) identified during the search (snowballing).

Search strategyA search strategy was developed using MESH terms and keywords on the use of artificial intelligence for the prediction of complications in patients treated with degenerative thoracolumbar spinal surgeries. The strategy was developed by the team of researchers and is described below: ((((((artificial intelligence) OR (deep learning)) OR (machine learning)) OR (AI)) OR (artificial intelligence)) AND (spine)) AND ((((thoracolumbar) OR (lumbar)) OR (thoracic)) OR (lumbosacral)). The bibliographical search was limited by language filters (Spanish, English and Portuguese) and by date, considering the period of time as between 1st January 2000 and 1st May 2023. We did not use search filters on study design or type.

Data managementThe results of the literature search were uploaded to the Zotero programme, which manages bibliographical citations and facilitate collaboration between reviewers during the study selection process. Abstracts were uploaded and duplicates were deleted. Prior to the formal selection process, training was provided for the members of the review team who were unfamiliar with the programme.

Selection processThe review authors were grouped into 2 groups of 2 members each; both groups independently screened titles and abstracts according to inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion among the reviewers and, eventually, by a third opinion from an additional reviewer, an experienced member of the research team. After the selection of articles eligible for full-text review, all full-text articles were retrieved through library sources. Both groups of reviewers proceeded to assess the full-text articles that had been selected by the other team, and vice versa, (cross-design) to limit possible review selection bias. During the full-text review, the references of the articles were also checked for possible eligibility (snowball). Again, any potential conflicts were resolved first by the reviewers in each group and, if necessary, by the third opinion of an additional experienced reviewer.

Data miningData mining was undertaken in duplicate and the review authors in charge worked independently. Data was recorded in tables. A table on the characteristics of the selected studies included the following: author, year, participating countries, disease under study, algorithm used, number of sites participating, sample size, outcome variable (general complications or of a specific type), data source (database), validation, reported results, accuracy (percentage), area under the curve (AUC ROC) and operating characteristics (sensitivity, specificity). Inclusion and exclusion criteria, demographic characteristics of participants, follow-up period, data on funding and possible conflicts of interest were also recorded.

Assessing risk of biasWe assessed the risk of bias of non-randomised observational studies using the ROBINS-I5 tool. To assess the risk of bias in the use of predictive risk models, the PROBAST6 tool was considered. Bias assessment was performed by at least 2 evaluators independently. Conflicts were resolved by consensus.

To ensure consistency, the lead author screened all abstracts and full texts for eligibility, mined the data, and assessed risk of bias in all studies included.

Strategy for data synthesisSubsequently, all the results of the individual reviewers were combined into one single data table. This table was discussed with the full team of reviewers to reach a consensus over the results of our review.

For the assessment of the performance of the predictive models, the AUC was mainly considered. For its categorisation the following classification was adopted: AUC=0.5 useless, AUC=0.6–0.7 possibly useful; AUC=0.7–0.8 acceptable; AUC=0.8–0.9 excellent and AUC>0.9=exceptional.

On the other hand, other parameters that reflect the performance of the predictive models were considered: accuracy, recall, specificity, positive predictive value (precision).

To assess the effectiveness of predictive models compared to other methods, we consider as alternatives the use of instruments such as scales or scores and comparison with traditional statistical methods, either linear regression or multivariate logistic regression. These methods of statistical analysis mentioned are most typically used to generate predictive clinical models or prognoses and their use can be considered as a benchmark performance indicator. It should be clarified that any type of more advanced algorithm can be considered as a form of ML.

ResultsA total of 2321 titles were identified, of which 763 were duplicates. Screening was run on 1558 titles, of which 22 were chosen for complete reading.8–29 A total of 18 articles were excluded according to the proposed selection criteria.9–17,20–28 Finally, 4 articles were chosen for the next review.8,18,19,29 In addition, 8 publications were retrieved from other sources (Library of the Argentine Association of Orthopaedics and Traumatology and manual search for citations or snowballing).30–37Fig. 1 presents the PRISMA flowchart.

All studies included describe the development and internal validation of predictive models based on the use of AI for the prediction of complications in thoracolumbar spinal surgery as a result of degenerative disease. We did not find any studies that carry out external validation of previously developed predictive models.

According to the type of degenerative disease, 7 publications (58.3%) included patients with adult scoliosis30–34,37; 4 (33%) included patients with degenerative disease in general (not scoliosis)18,19,29,36 and one (8.33%) with patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis, exclusively.8

Although all publications assess complications as a primary outcome, the variable “complications” had different definitions in all the publications. In 5 articles (41.6%), perioperative complications were assessed as the primary outcome, including clinical and surgical complications, with no consensus on the definition.8,31,37 In 2 articles (16.6%) surgical site infection was considered19,29; in 2 (16.6%) kyphosis or proximal junction failure32,33; one (8.33%) grouped mechanical complications (proximal junction failure, proximal junction kyphosis, implant complications, bar rupture),30 in another (8.33%) pseudoarthrosis34 and in another (8.33%) deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary thromboembolism.18Table 2 summarises the characteristics of the studies included.

Study characteristics.

| Author (year); institutions, country. | Pathology | Selection criteria | Machine learning algorithm | Demographic data | Follow-up | Sample split % training: validation | Outcome | Funding and conflict of interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. (2018)37Multicentre study; US | ASD | Inclusion: Patients aged over 18 years undergoing ASD surgery.Exclusion: Patients with missing preoperative data, emergency cases, class 2, 3 or 4 wounds, open wounds on the body, sepsis, pneumonia, previous surgeries within 30 days, cardiopulmonary resuscitation before surgery, or spinal neoplasm. | LR and ANN | Sample: 5794 – M: 2376 (41%) – F: 3418 (59%) Age; mean 59.5 (DE: NR) | 2010–2014 | 70:30 | Complications:- Cardiac complications- PE/DVT- Wound | No |

| Noh et al. (2023)30Single centre; Korea | ASD | Inclusion: Spine surgery for ASD and one or more radiological criteria (Coronal Cobb angle greater than 20°; sagittal vertical axis greater than 5cm; pelvic tilt greater than 25°; TK>60°; PI-LL>10°; fixation of at least 4 levels); Follow-up for a period of 2 years or more.Exclusion: Syndromic deformity, autoimmune disease, infection, tumour, or any other pathological conditions. | LR; Gradient boosting; Random forest; ANN | Sample: 238 – M: 34 (14%) – F: 204 (86%) Age; mean: NR (training set: 67.8±7.49; validation set: 66.94±6.98 years old) | 2009–2017; Follow-up>2 years | 70:30 | Mechanical complications | No |

| Yagi et al. (2018)33Single centre; Japan | ASD | Inclusion: ASD patients aged≥50 years, meeting radiological criteria (Cobb angle≥20°; C7 SVA≥5cm; PT≥25°), with fusion of ≥5 levels, and minimum follow-up of ≥ 2years. Exclusion: Poor quality radiographs; syndromic, neuromuscular or other spinal pathologies. | DNDT; To build a Decision-making Tree C5.0 | Sample n=145 Sex and age NR. Group Training: n=112 sex M:F (5:107); age (63.9±9.4). Group Validation: n=33 Age and sex NR | Study period: NR; Follow-up: 2 years | 70:30 | PJK/PJF | NO |

| Scheer et al. (2016)32Multicentre; USA | ASD | Inclusion: Patients aged over 18 years old; Radiological criteria: coronal Cobb angle≥20°; C7 SVA≥5cm; PT≥25°; and/or thoracic kyphosis greater than or equal to 60°; Fusion of 4 or more levels was required; A minimum follow-up period of 2 years was required.Exclusion: Patients with neuromuscular deformity, infection or malignancy were excluded from the study. | DNDT; Decision-making Tree C5.0 | Sample: 510; Sex F:M (396:114); Age. 57.2±13.9 years old. | Period: NR; Follow-up: 2 years | 70:30 | PJK/PJF | Yesa |

| Scheer et al. (2018)34Multicentre; USA. | ASD | Inclusion: Participants aged over 18 years oldRadiological criteria: Cobb angle≥20°; C7 SVA≥5cm; PT≥25°; and/or thoracic kyphosis greater than or equal to 60 degrees.Fusion of 4 or more levels was required.A minimum follow-up period of 2 years was required.Exclusion: neuromuscular deformities, infections, and malignancies. Revision surgery was indicated only if there were reasons other than pseudoarthrosis. | DNDT; Decision-making Tree C5.1 | Sample: 336; F:M=268:68; Age. mean 57.7±15.1 years old. | Period: NR; Follow-up: 2 years | Validation set n=126 (randomised). | Pseudoarthrosis | Yesa |

| Pellisé et al. (2019)35Multi-centre: Spain USA, Switzer-land, Turkey, France. | ASD | Inclusion: Age>18 years. Radiological criteria: Cobb coronal≥20°; SVA≥5cm; PT≥25°; and/or thoracic kyphosis greater than or equal to 60 degrees.Exclusion: NR | Random forest | Sample n=1612; F:M NR; Age. mean NR.; Training (n=1289; F:M 1000:289; Age. mean 56.5±17.3); Validation (n=323; F:M 235:88; Age. mean 57.6±17.8) | 2008–2016; Follow-up 730 days | 80–20 | Major complication | Yesa |

| Xiong (2022)29Single centre; China. | DSD | Inclusion: Patients aged 18 years or older with degenerative lumbar disease which includes herniated disc, lumbar stenosis, spondylolisthesis, or instability and had undergone posterior lumbar interbody fusion (at least one level). Exclusion: history of spinal surgery, active infection or tumour, and deformity. | Boosted Classification Trees, Boosted Logistic Regression, Extreme Gradient Boosting, Stochastic Gradient Boosting, Generalised Linear Model, AdaBoost Classification Treesa, and a Forest. | Sample: 584; F:M 321:263; Age, mean 58.36±13:76 years old; Disc herniation: 284; Lumbar stenosis:137; spondylolisthesis/instability: 163. | 2019–2021 Follow-up: 90 days. | 50:50 | Surgical site infection | No |

| Fatima (2020)8Multicentre study; USA | DSD | Inclusion: Decompression surgery, arthrodesis or instrumentation of the lumbar spine; lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis; operated between 2005 and 2016; by neurosurgery or traumatology, under general anaesthesia and inpatients. Exclusion: NR | LR and LASSO: least absolute shrinkage and selection operator | Sample: 80,610; Age, median 58 years old (range:18–89); F:M 38,874:41,654. | 2005–2016 Follow-up: 30 days | 70:30 | Advetrse events | No |

| Zehnder (2021)36Multicentre study. Switzer-land, UK, Italy. | DSD | Inclusion: spinal surgery for degenerative lumbar disease; Age 18–95 years. Exclusion: cases with missing data. | Shrinkage Algorithm (dfbeta method) | Sample: 23,714; F:M 12,264:11,450; Age. mean 58.9±15.7 years old. | 2012–2017 Follow-up until hospital dis-charge. | NR | Surgical complications: perioperative and general. | No |

| Scheer (2017)31Multicentre study; USA | ASD | Inclusion: Age>18 years Radiological criteria: coronal Cobb≥20°; SVA≥5cm; PT≥25°; or thoracic kyphosis≥60°. Exclusion: neuromuscular deformity, infection or malignant neoplasia. | DNDT; Decision-making Tree C5.0 | Sample: 557 F:M=439:118; Age. mean 57.5±15.3 years old. | Period: NR; Follow-up: 6 weeks. | 70:30 | Major complication | Yesa |

| Wang (2021)18Multi-centre study. USA | DSD | Inclusion: posterior lumbar fusion (1 level). Exclusion: trauma, tumours, revision surgery. | XGBoost (extreme gradient boosting) | Sample n=13,500 Age. categories n(%): 19–34 years old=490 (3.63); 35–49 years old=2146(15.9); 50–65 years old=5050 (37.41); >65 years old=5814(43.07). F:M 7516:5984. | 2010–2017 Follow-up: 30 days. | 80:20 | PE/DVT | No |

| Liu (2022)19Single centre; China | DSD | Inclusion: degenerative low back disease (canal stenosis; herniated disc; degenerative spondylolisthesis); single posterior approach surgery; elective surgery. Exclusion: emergency surgery. | RL, multilayer perceptron, decision tree, random forest, gradient boosting machine, and XGBoost (extreme gradient boosting) | Sample: 288; Age. mean: 55.3±12.3 F:M NR | 2010–2019Follow-up: NR | 70:30 | Surgical site infection | Yesa |

Abbreviations: ASD=adult spinal deformity; ANN=artificial neural network; DNDT=deep neural decision tree; F:M=female:male; NR=not reported; SD=standard deviation; PE/DVT=pulmonary embolism/deep venous thrombosis; PJK/PJF=proximal junctional kyphosis/failure; SVA: sagittal vertical alignment; PT=pelvic tilt; PI=pelvic incidence; PI-LL=pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis.

The measures commonly used to assess the performance of predictive models were the area under the curve (n=12; 100%) and the accuracy of the model (n=7; 58.3%). To a lesser extent, sensitivity (recall; n=4; 33%, specificity n=3; 25%) and, rarely, positive predictive value (accuracy) were reported. The performance of the predictive models was variable, depending on the outcome considered (general versus specific complications) and the type of machine learning model used. Taking the model with the best performance of each publication, the area under the curve (AUC) ranged between 0.6 and 1.0; and was excellent or exceptional (AUC>0.8) in more than half of the publications (n=7; 58.3%).19,29–34 In the other 5 publications, the performance according to the AUC was acceptable (AUC=0.7–0.8) in at least one of the outcome variables analysed.8,18,35–37 Half of the studies did not report the estimated AUC accuracy (95%CI). The results of the studies are described in Table 3.

Results of the studies.

| Author (year). centres; country. | Pathology | Data origin | Algorithm | Outcome | Model performancea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (CI 95%) | AUC–ROC (CI 95%) | Recall (CI 95%) | Specificity (CI 95%) | Observations | |||||

| Kim et al. (2018)37Multicentre study; United States | ASD | NSQIP | LR and ANN | Complications:- Cardiac complications- PE/DVT- Wound | NR | Cardiac complications=0.768 (0.76–0.77) PE/DVT=0.542 (0.53–0.55) Wound=0.606 (0.60–0.61) | Wound=0.657(NR) | Wound=0.587 (NR) | Better results with ANN (Except for PE/DVT). |

| Noh et al. (2023)30Single centre; Korea | ASD | RC | LR; Gradient boosting; Random forest; DNN | Mechanical complications | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | Better results with random forest |

| Yagi et al. (2018)33Single centre; Japan | ASD | RC | DNDT; To build a Decision-making Tree C5.0 | PJK/PJF | 0.981 (NR) | 1.0 (NR) | NR | NR | Better results including the predictive variable “T-score≤−1.5” |

| Scheer et al. (2016)32Multicentre study.United States | ASD | RC | DNDT; Decision-making Tree C5.0 | PJK/PJF | 0.863 (NR) | 0.89 (NR) | NR | NR | – |

| Scheer et al. (2018)34Multicentre study;United States. | ASD | RC | DNDT; Decision-making Tree C5.1 | Pseudoarthrosis | 0.876 (NR) | 0.89 (NR) | NR | NR | – |

| Pellisé et al. (2019)35Multicentre study;Spain, United States, Switzerland, Turkey, and France. | ASD | RC | Random forest | Major complications | NR | 0.717 (0.68–0.75) | NR | NR | – |

| Xiong (2022)29Single centre; China. | DSD | RC | Boosted Classification Trees, Boosted Logistic Regression, Extreme Gradient Boosting, Stochastic Gradient Boosting, Generalised Linear Model, AdaBoost Classification Treesa, and Random Forest. | Surgical site infection | 0.8247 (NR) | 0.906 (NR) | 0.9375 (NR) | 0.818 (NR) | Better results with AdaBoost Classification Tress |

| Fatima (2020)8Multicentre study; USA. | ESD | NSQIP | LR and LASSO: least absolute shrinkage and selection operator | Adverse events | NR | General: 0.70 (0.62–0.74); Surgical complications 0.70 (NR); Clinical complications 0.70 (NR) | NR | NR | Better results with LR |

| Zehnder (2021)36Multicentre study. Switzerland, UK, Italy. | DSD | EUROSPINE Spine Tang | Shrinkage Algorithm (dfbeta method) | Surgical complications: perioperative and general. | NR | Generales 0.74 (0.72–0.76); Quirúrgicas 0.64 (0.62–0.65). | NR | NR | – |

| Scheer (2017)31Multicentre study; USA | ASD | RC | DNDT; Decision-making Tree C5.0 | Major Complication | 0.876 (NR) | 0.89 (NR) | NR | NR | – |

| Wang (2021)18Multicentre study. USA | DSD | NSQIP | XGBoost (extreme gradient boosting) | PE/DVT | NR | 0.716 (0.701–0.731) | NR | NR | – |

| Liu (2022)19Single centre; China | DSD | RC | LR, multilayer perceptron, decision tree, random forest, gradient boosting machine, and XGBoost (extreme gradient boosting) | Surgical site infection | 0.860 (NR) | 0.923 (NR) | 0.834 (NR) | NR | Better results with XGBoost |

Abbreviations: ANN=artificial neural network; ASD=adult spinal deformity; AUC=area under the curve; DNDT=deep neural decision tree; DNN=deep neural network; DSD=degenerative spine disorders; LR=logistic regression; NR=not reported; NSQIP=The National Surgical Quality Improvement Programme; PE/DVT=pulmonary embolism/deep vein thrombosis; PJK/PJF=proximal junctional kyphosis/proximal junctional failure; RC=retrospective cohort; SSIs=surgical site infections.

In 5 publications (41.6%), the effectiveness of predictive AI models for the prediction of general or specific complications was compared.8,18,19,30,37

Kim et al. compared the performance of the artificial neural network (ANN)-based machine learning predictive algorithm with logistic regression and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) pre-anaesthesia assessment scale for the prediction of 3 outcome variables (cardiac complications, deep vein thrombosis/lung thromboembolism/wound complications. AUC performance of the AI predictive algorithm was superior in 2 of the 3 outcomes estimated by logistic regression (except for the prediction of deep vein thrombosis/lung thromboembolism) and in all with respect to the ASA scale. Additionally, the sensitivity of ANN was higher than logistic regression in predicting wound complications37: [ANN AUC: cardiac complications 0.768 (95%CI 0.76–0.77); DVT/PTE: 0.542 (95%CI 0.53–0.55); wound complications 0.606 (95%CI 0.60–0.61). Logistic regression AUC: cardiac complications 0.690 (95%CI 0.68–0.69); DVT/PTE: 0.547 (95%CI 0.54–0.55); wound complications 0.575 (95%CI 0.56–0.58); wound complications 0.575 (95%CI 0.56–0.58): 0.56–0.58); ASA AUC: cardiac complications 0.469 (95%CI: 0.46–0.47); DVT/PTE: 0.485 (95%CI: 0.47–0.49); wound complications 0.508 (95%CI: 0.50–0.51)].

In the publication by Wang et al. on the prediction of deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary thromboembolism, the AUC for the predictive model (0.716; 95% CI: 0.701–0.731) of machine learning was significantly higher (p<0.001) than the AUC for the ASA and the Charlson Comorbidity Index.18

Noh et al. compared 3 predictive machine learning models (gradient boosting, random forest and deep neural network) with logistic regression. The random forest AI model [AUC=1.000 (95%CI: 1.000–1.000)] achieved the best predictive performance.30

Fatima et al. compared the predictive machine learning model (LASSO) with 2frailty indices (mFI-5 and mFI-11) and with the logistic regression method. The performance of the AI-based predictive model [AUC: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.61–0.69] was lower than that of logistic regression [AUC=0.70; 95% CI: 0.62–0.74] for the general prediction of adverse events and for specific events. However, the performance was significantly better (p<0.001) than for the 2 frailty indices [mFI-5 AUC=0.50 (95% CI: 0.47–0.53); mFI-11 AUC=0.56 (95% CI: 0.54–0.59)].8

Liu et al. compared the performance of 6 predictive models including logistic regression (AUC=0.871) and determined that the extreme gradient boosting model had the best predictive performance (AUC=0.923).19

Risk of biasUsing the Robins-E (The Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies of Exposure) tool for the assessment of risk of bias in non-randomised observational studies, all articles included were globally catalogued as having very high risk of bias, high or very high risk in almost all domains of the tool (confounding, exposure measurement, selection of participants, data lost (Fig. 2).

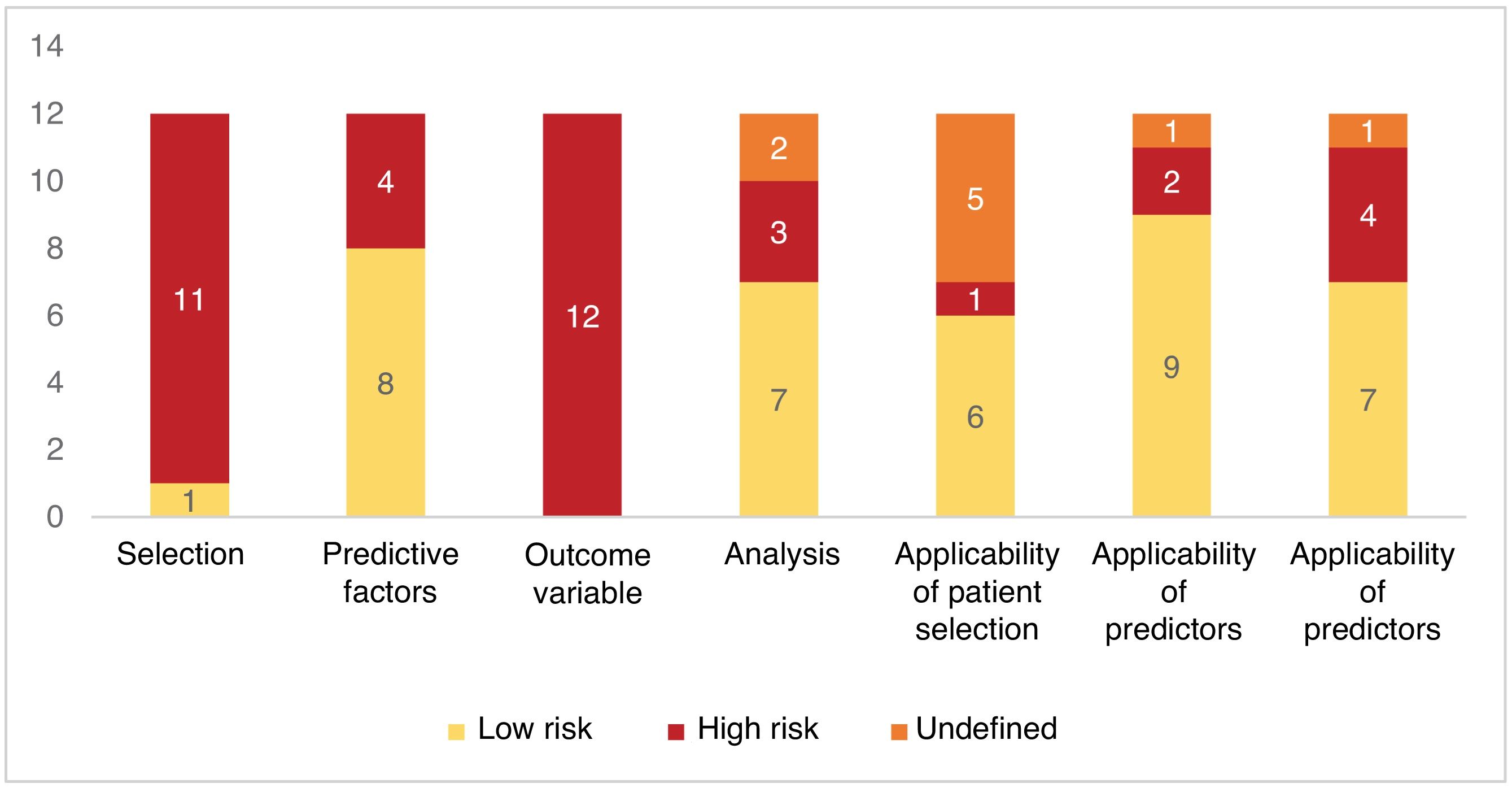

With the PROBAST (Prediction Model Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool) tool, all studies (n=12; 100%) were at high risk of bias in at least one of the 4domains that make up the scale (selection bias; bias associated with predictive factors; bias in outcome assessment; analysis bias). Patient selection and outcome endpoint assessment were the 2 most frequently assessed domains at high risk of bias (Fig. 3).

Given the heterogeneity of the samples (cohorts or databases), the results of interest (definition of complications) and the evaluation metrics of the algorithms, a meta-analysis was not performed.

DiscussionThe field of AI includes a variety of areas with current or potential applications in health care. Among these are ML (the focus of this review); natural language processing used in chatbots; augmented, mixed and virtual reality; and robotic surgery. These technologies not only impact spinal surgery but also broad areas of medical practice and other disciplines.3,4,38

Machine learning is a branch of AI that enables computers to learn. It involves the development of algorithms that improve their performance with experience, and the incorporation of new data into the system enables them to improve their performance.7 Machine learning has a wide range of applications, one of these being the development of multivariable predictive models.3,4 A multivariate prediction model is a mathematical equation that relates multiple predictors (risk factors, predictive, independent variables, covariates) for a particular individual to the probability or risk of the presence (diagnosis) or future occurrence (prognosis) of a particular outcome.38 The development of predictive models involves the selection of predictors and their combination in a multivariate model. Traditionally, the estimation of multivariate prognostic outcomes was based on statistical techniques, such as logistic regression and Cox regression.37 The use of AI techniques makes it possible to address a limiting factor of traditional statistical methodology, which is the condition that statistical power decreases as the dimension of multivariate analysis increases. In addition, machine learning does not necessarily propose a predetermined hypothesis at the beginning of the study and algorithms can correlate information and associations, which might otherwise have been overlooked or unnoticed due to their complexity and multifactorial origins.3

In this review, the authors set out to assess the effectiveness of AI-based predictive models for predicting complications in patients treated with degenerative thoracolumbar spinal surgery. As a result, we found no robust evidence in favour of the performance of AI-based algorithms, compared to other traditional predictive methods. Studies of development and internal validation of predictive models with good performance according to the AUC predominated, which ranged mostly between acceptable and excellent. However, only 5 (41%) studies compared their performance with traditional statistical techniques or with scales or scoring systems.8,18,19,30,37

The evidence was weak, due to the high risk of bias in all studies, with bias predominating in the assessment of the outcome variable and the selection of patients. In the retrieved publications, there was a heterogeneity in the definition of the outcome variable “complications” that prevented the synthesising of the data and guiding a recommendation. Sometimes, the definition of perioperative complication included those that occurred during the intraoperative and immediate postoperative periods, which, according to the researchers, is a weakness, since these can be conditioned by different risk variables and grouping them together adds to the possibility of confounding bias.8,31,35,36 On the other hand, in some of the publications, the estimate of the complication was made based on the information available in national databases, previously set up for a different purpose and with limited follow-up time (30 days).18,37

It should be noted that, in a surgical specialty whose performance may be conditioned by the environment, the experience of the surgeons and institutions, and the resources and characteristics of the health care system in each country or region, it is difficult to express the benefits of predictive algorithms of surgical complications on samples made up of retrospective cohorts in a single centre, non-representative multicentre cohorts, databases prepared for a different purpose, or samples obtained by non-probabilistic sampling techniques subject to selection bias. In addition, we could mention other main sources of bias in the publications included in this review such as: the lack of prospective studies or samples of randomly selected cases, or the absence of external validation studies of predictive algorithms that enable make it possible to estimate their performance with data outside the database used for their development, training and validation. Only half of the articles published the points estimated (e.g. the AUC) with their respective confidence intervals, which made it impossible to assess the accuracy of these estimates.

Despite the above and the evident low quality of the available evidence, the authors observed a trend towards a benefit of the use of AI-based predictive models as a tool to establish the individual risk of complications of spinal surgery in patients with degenerative thoracolumbar vertebral disease. In the near future, these techniques could guide the decision-making of spinal surgeons. Estimating the surgical risk in a given patient represents a real challenge due to the large number of variables that interact in a complex manner and impact on the overall risk. Variables include some characteristics that can be generalised along with others that are specific to the environment. Therefore, the recording of local and regional data is the basis for the development of future predictive algorithms that enable us to recognise the risk of our patients with accuracy and precision.

The predominant limitations of this review are that some relevant literature may not have been retrieved because the search was done exclusively in the MEDLINE, Cochrane Library and Lilacs databases. The search was restricted to articles in English, Spanish and Portuguese. In addition, the grey bibliography was not consulted. There is consensus, however, on the adequate reporting of predictive algorithm research, which would enable a more rigorous selection of articles for data synthesis. Nevertheless, the scarcity of available studies and the lack of previous systematic reviews on the topic led the authors of the present review to adopt more flexible eligibility criteria.

ConclusionsThis systematic review provides an up-to-date view of the application of predictive AI models, in particular, machine learning, for the identification of the risk of complications in patients treated with surgery for degenerative disease of the thoracolumbar spine. Although the available evidence is limited and at high risk of bias, the studies analysed indicate that these models may have a promising performance in predicting complications, with AUC values, ranging mostly from acceptable to excellent. Future research with regional databases, more robust methodologies and external validations are needed to improve the reliability and applicability of these models.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Ethical considerationsThe following paper is a systematic review of the literature, based on data from published primary studies, and is therefore exempt from evaluation by an ethics committee. It does not include primary data from patients or animals.

FundingNo external funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors thank Dr. Víctor Barrientos, from the Hospital del Trabajador (Santiago, Chile) for his help with the methodology.