This systematic review aimed to evaluate the current applications, clinical outcomes, and limitations of artificial intelligence (AI) in orthopedic surgery across diagnostics, pre-surgical planning, robotic-assisted interventions, and postoperative care.

MethodsA comprehensive search across PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar (2018–2025) identified 125 studies, of which 47 met inclusion criteria.

ResultsAI-based imaging tools demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy, with some models achieving sensitivities up to 98.2% and area under the curve (AUC) values exceeding 0.95 in fracture detection and musculoskeletal anomaly identification. In pre-surgical planning, AI-driven 3D modeling improved implant conformity (acetabular cup 90.9% vs. 72.2%; femoral stem 87.3% vs. 66.7%) and enhanced surgical risk prediction (AUC>0.85 for complications). Robotic-assisted surgeries incorporating AI-guided planning improved implant alignment and procedural consistency, although long-term functional outcomes remained inconclusive. In the postoperative setting, 17 of 18 trials using wearable or app-based interventions reported improved functional recovery, patient satisfaction, and adherence.

ConclusionAI is playing an increasingly important role in orthopedic surgery, offering promising improvements in diagnostic accuracy, surgical precision, and rehabilitation support. However, challenges remain regarding external validation, algorithmic bias, and regulatory frameworks.

Esta revisión sistemática tuvo como objetivo evaluar las aplicaciones actuales, los resultados clínicos y las limitaciones de la inteligencia artificial (IA) en la cirugía ortopédica en las áreas de diagnóstico, planificación prequirúrgica, intervenciones asistidas por robots y cuidados postoperatorios.

MétodosSe realizó una búsqueda exhaustiva en PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science y Google Scholar (2018–2025), que identificó 125 estudios, de los cuales 47 cumplieron los criterios de inclusión.

ResultadosLas herramientas de diagnóstico por imagen basadas en IA demostraron una alta precisión diagnóstica, con algunos modelos que alcanzaron sensibilidades de hasta el 98,2% y valores de área bajo la curva (AUC) superiores a 0,95 en la detección de fracturas y la identificación de anomalías musculoesqueléticas. En la planificación prequirúrgica, la modelización 3D impulsada por IA mejoró la conformidad de los implantes (copa acetabular 90,9% vs. 72,2%; vástago femoral 87,3% vs. 66,7%) y reforzó la predicción de riesgos quirúrgicos (AUC >0,85 para complicaciones). Las cirugías asistidas por robots que incorporaron planificación guiada por IA mejoraron la alineación de los implantes y la consistencia de los procedimientos, aunque los resultados funcionales a largo plazo fueron inconclusos. En el contexto postoperatorio, 17 de 18 ensayos que utilizaron dispositivos portátiles o aplicaciones móviles informaron una mejor recuperación funcional, mayor satisfacción del paciente y mejor adherencia.

ConclusiónLa IA está desempeñando un papel cada vez más importante en la cirugía ortopédica, ofreciendo mejoras prometedoras en precisión diagnóstica, exactitud quirúrgica y apoyo en la rehabilitación. No obstante, persisten desafíos en torno a la validación externa, el sesgo algorítmico y los marcos regulatorios.

AI, defined as the simulation of human intelligence processes by computer systems, is gaining increasing interest across various sectors, particularly in healthcare. In medicine, AI encompasses machine learning (ML), deep learning, and natural language processing, enabling capabilities such as data analysis, predictive modeling, and clinical decision support systems. The healthcare industry has seen a rise in exploratory AI applications aimed at improving diagnostic accuracy, personalizing treatment strategies, and supporting patient management. For instance, AI algorithms have been proposed to predict surgical complications, thereby supporting preoperative planning and patient counseling.1

In orthopedic surgery, AI is emerging as a promising adjunct tool. The specialty's reliance on imaging, biomechanical modeling, and patient-specific variables positions it well for AI integration. AI has been applied to diagnostic imaging, where machine learning models assist in identifying fractures and musculoskeletal tumors with increasing accuracy.2 Additionally, AI supports preoperative planning by generating patient-specific 3D anatomical models, enabling more detailed surgical simulations and aiding implant selection.3 Intraoperatively, robotic systems incorporating AI-based planning tools aim to enhance surgical precision, with the potential to improve alignment and procedural consistency.4 Postoperatively, AI technologies are being explored for monitoring recovery and guiding personalized physiotherapy regimens through predictive analytics.5

This literature review examines current applications of AI in orthopedic surgery, with a focus on diagnostic imaging, pre-surgical planning, robotic-assisted procedures, and post-operative care. While the promise of AI is substantial, many implementations remain in early stages of clinical validation. This review also outlines the challenges and limitations that must be addressed to ensure safe, equitable, and effective integration of AI into orthopedic practice. Therefore, the primary aim of this systematic review is to critically evaluate and synthesize the available evidence on AI applications in orthopedic surgery. Specifically, the review seeks to answer the following question: What are the current applications, clinical outcomes, limitations, and future perspectives of artificial intelligence in orthopedic surgery?

MethodologySearch strategyA systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2020 guidelines to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigor. The review was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO database (Registration ID: CRD420251153398). Comprehensive searches were performed across four major databases: PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search included studies published from January 1, 2018, to January 15, 2025, and was limited to peer-reviewed articles written in English.

The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms related to artificial intelligence and orthopedic surgery. Boolean operators were used to refine and expand the search. An example search string used in PubMed was: (“Artificial Intelligence” OR “Machine Learning” OR “Deep Learning”) AND (“Orthopedic Surgery” OR “Musculoskeletal Surgery”) AND (“Imaging Analysis” OR “Robotic-Assisted Surgery” OR “Post-Operative Care”).

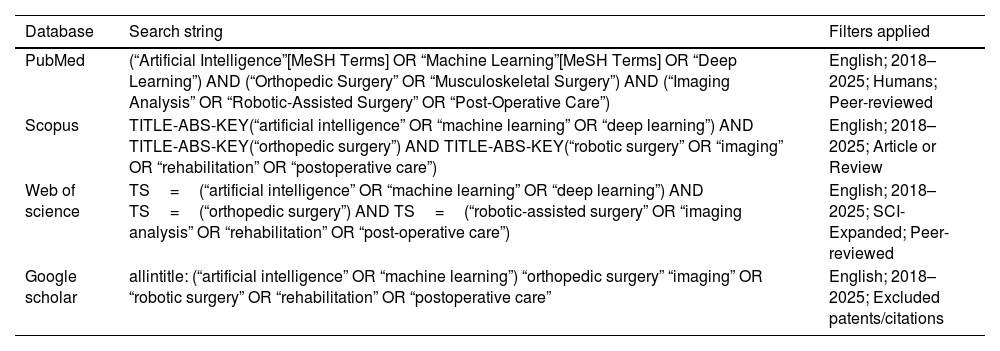

To ensure rigor, the PubMed strategy was peer-reviewed by an independent librarian using the PRESS (Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies) checklist. Detailed search strategies for each database are provided in Table 1.

Search strategies used across databases.

| Database | Search string | Filters applied |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“Artificial Intelligence”[MeSH Terms] OR “Machine Learning”[MeSH Terms] OR “Deep Learning”) AND (“Orthopedic Surgery” OR “Musculoskeletal Surgery”) AND (“Imaging Analysis” OR “Robotic-Assisted Surgery” OR “Post-Operative Care”) | English; 2018–2025; Humans; Peer-reviewed |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“orthopedic surgery”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“robotic surgery” OR “imaging” OR “rehabilitation” OR “postoperative care”) | English; 2018–2025; Article or Review |

| Web of science | TS=(“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”) AND TS=(“orthopedic surgery”) AND TS=(“robotic-assisted surgery” OR “imaging analysis” OR “rehabilitation” OR “post-operative care”) | English; 2018–2025; SCI-Expanded; Peer-reviewed |

| Google scholar | allintitle: (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning”) “orthopedic surgery” “imaging” OR “robotic surgery” OR “rehabilitation” OR “postoperative care” | English; 2018–2025; Excluded patents/citations |

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

- •

Language: English

- •

Focus: Application of AI specifically within orthopedic surgery

- •

Study design: Original research, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses

- •

Date range: Published between January 2018 and January 2025

- •

Non-peer-reviewed material (e.g., editorials, commentaries, abstracts)

- •

Studies not directly addressing AI implementation in orthopedic surgery

The search initially identified 125 articles. After removing duplicates using EndNote and Mendeley, 99 unique records remained. These underwent a two-stage screening process:

- 1.

Title and abstract screening for relevance

- 2.

Full-text screening based on eligibility criteria

Two reviewers independently screened all titles/abstracts and subsequently full texts. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and if consensus could not be reached, a third independent reviewer adjudicated. After screening, 47 studies met the inclusion criteria.

Data extractionData were extracted using a standardized form and included:

- •

Study characteristics: Authors, year, country, and study type

- •

AI methodology: Type of AI used (e.g., ML, DL, NLP), clinical application

- •

Clinical context: Targeted orthopedic condition, patient group

- •

Outcomes: Key findings, limitations, and reported challenges

Two reviewers independently extracted data. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or, when necessary, adjudicated by a third reviewer. No software (e.g., WebPlotDigitizer) was used to extract data from figures; all information was extracted manually.

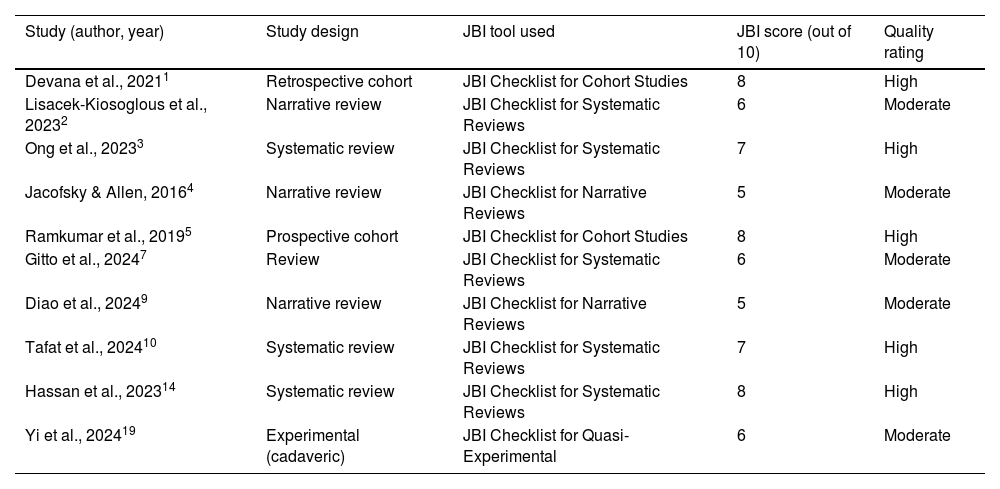

Quality assessmentStudy quality was evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools, appropriate to the study type. Each study was scored out of 10 based on JBI criteria:

- •

High quality: Score of 7 or above

- •

Moderate quality: Score between 4 and 6

- •

Low quality: Score of 3 or below (excluded)

Two reviewers independently conducted quality assessments, with disagreements resolved by a third reviewer. Only high- and moderate-quality studies were included in the synthesis. A summary of the appraisal is provided in Table 2.

Quality appraisal of selected included studies (JBI criteria).

| Study (author, year) | Study design | JBI tool used | JBI score (out of 10) | Quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devana et al., 20211 | Retrospective cohort | JBI Checklist for Cohort Studies | 8 | High |

| Lisacek-Kiosoglous et al., 20232 | Narrative review | JBI Checklist for Systematic Reviews | 6 | Moderate |

| Ong et al., 20233 | Systematic review | JBI Checklist for Systematic Reviews | 7 | High |

| Jacofsky & Allen, 20164 | Narrative review | JBI Checklist for Narrative Reviews | 5 | Moderate |

| Ramkumar et al., 20195 | Prospective cohort | JBI Checklist for Cohort Studies | 8 | High |

| Gitto et al., 20247 | Review | JBI Checklist for Systematic Reviews | 6 | Moderate |

| Diao et al., 20249 | Narrative review | JBI Checklist for Narrative Reviews | 5 | Moderate |

| Tafat et al., 202410 | Systematic review | JBI Checklist for Systematic Reviews | 7 | High |

| Hassan et al., 202314 | Systematic review | JBI Checklist for Systematic Reviews | 8 | High |

| Yi et al., 202419 | Experimental (cadaveric) | JBI Checklist for Quasi-Experimental | 6 | Moderate |

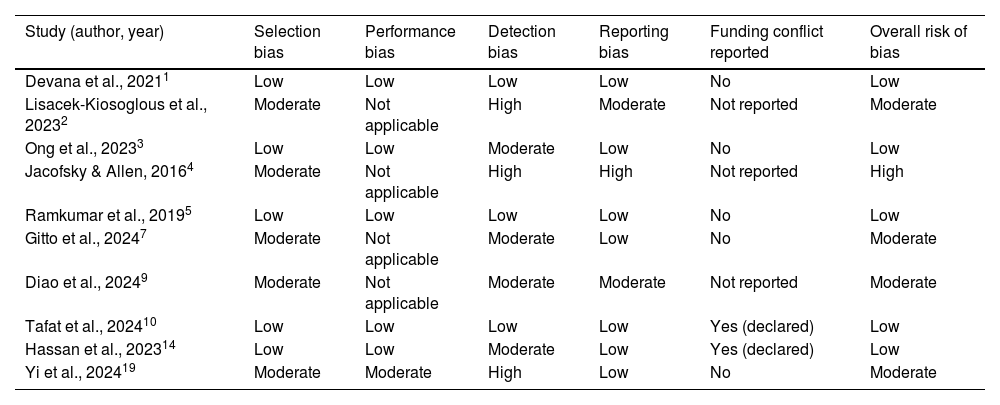

In accordance with PRISMA, a basic risk-of-bias assessment was conducted using JBI-derived criteria. Potential sources of bias included:

- •

Lack of blinding or control

- •

Small sample size or single-center data

- •

Absence of external validation for AI algorithms

Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias for each included study, with disagreements resolved by discussion or adjudication by a third reviewer. Each study was assessed for these risks, and outcomes are summarized in the risk-of-bias table (Table 3). Additionally, any funding sources or potential conflicts of interest reported in the studies were considered during this assessment.

Risk of bias assessment of selected included studies.

| Study (author, year) | Selection bias | Performance bias | Detection bias | Reporting bias | Funding conflict reported | Overall risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devana et al., 20211 | Low | Low | Low | Low | No | Low |

| Lisacek-Kiosoglous et al., 20232 | Moderate | Not applicable | High | Moderate | Not reported | Moderate |

| Ong et al., 20233 | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | No | Low |

| Jacofsky & Allen, 20164 | Moderate | Not applicable | High | High | Not reported | High |

| Ramkumar et al., 20195 | Low | Low | Low | Low | No | Low |

| Gitto et al., 20247 | Moderate | Not applicable | Moderate | Low | No | Moderate |

| Diao et al., 20249 | Moderate | Not applicable | Moderate | Moderate | Not reported | Moderate |

| Tafat et al., 202410 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Yes (declared) | Low |

| Hassan et al., 202314 | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Yes (declared) | Low |

| Yi et al., 202419 | Moderate | Moderate | High | Low | No | Moderate |

For interpretation, thresholds were defined a priori: an AUC>0.85 was considered indicative of good diagnostic or predictive accuracy, values between 0.70 and 0.85 were considered moderate, and values<0.70 were considered poor. These thresholds were selected based on standards commonly applied in diagnostic accuracy reviews.

Data synthesisDue to heterogeneity in study design, methodology, and outcome reporting, a narrative synthesis approach was adopted. Studies were thematically grouped into four domains:

- 1.

Diagnostic imaging

- 2.

Pre-surgical planning

- 3.

Robotic-assisted surgery

- 4.

Post-operative care

Eligibility for synthesis was based on study quality (high or moderate), methodological relevance, and availability of outcome data related to the four thematic domains. Studies that lacked extractable outcomes, did not meet minimum quality thresholds, or addressed AI in general medicine without specific orthopedic application were excluded from synthesis.

Quantitative data were summarized descriptively when appropriate, but no meta-analysis was conducted. To improve transparency, a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram is included, and a PRISMA checklist is provided in Supplementary material.

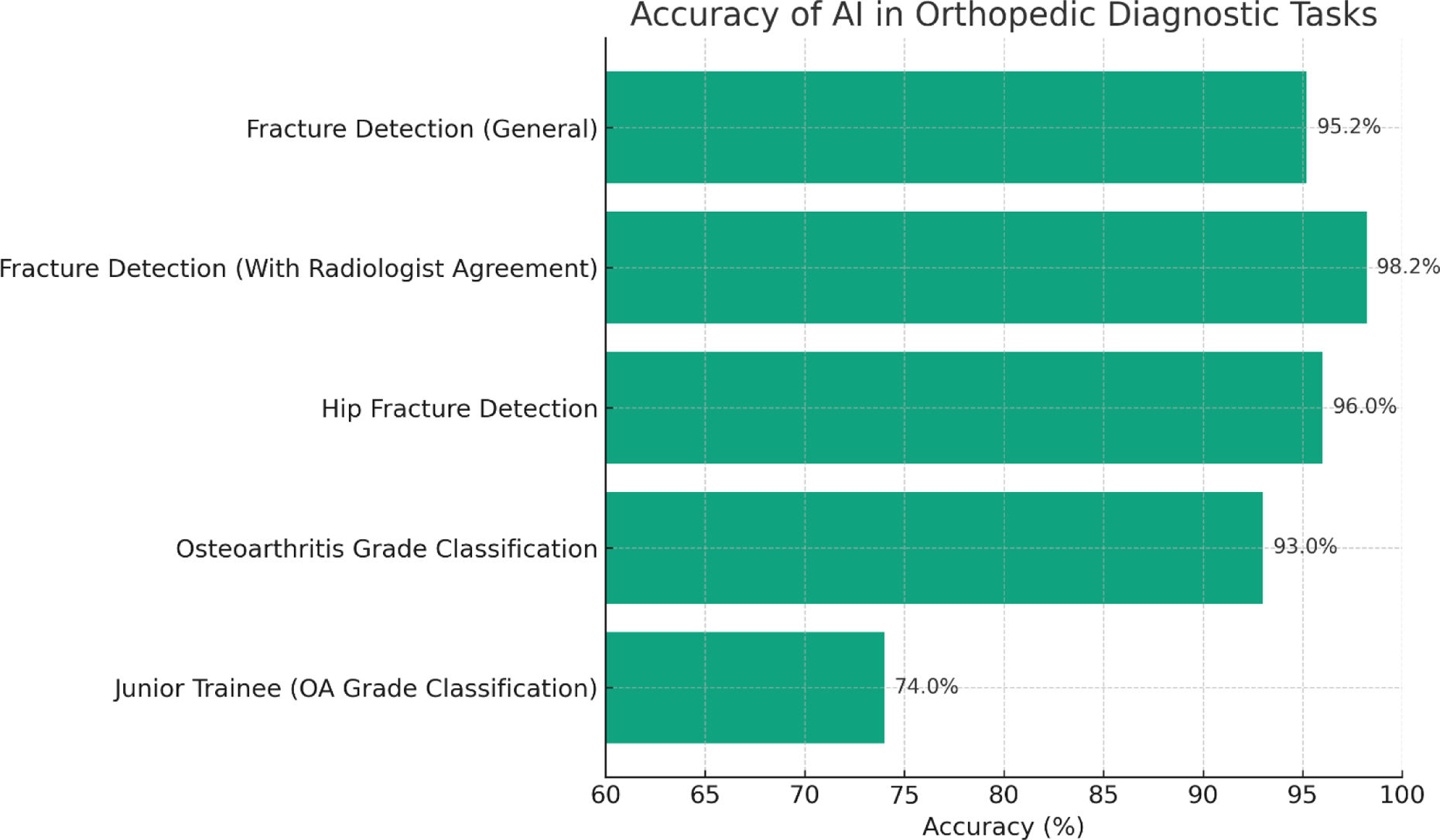

ResultsAI in diagnosis and imaging analysisArtificial Intelligence has significantly advanced the field of orthopedic diagnostics, particularly in the analysis of medical imaging. By leveraging machine learning algorithms, AI systems can interpret imaging modalities such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with notable accuracy. In fracture detection, for instance, deep learning models have been trained to identify subtle fractures that may be overlooked by the human eye. A narrative review by Chen et al. (2022)6 highlighted that AI algorithms have demonstrated performance comparable to, and sometimes exceeding, that of experienced radiologists in detecting fractures on radiographs. For example, large multicenter studies have reported an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.974, with a sensitivity of 95.2% and specificity of 81.3%, and even higher accuracy when there was radiologist agreement, reaching AUC 0.993 and sensitivity 98.2% (Fig. 1, which summarizes pooled diagnostic accuracies from included studies, directly supports these findings). Similarly, hip fracture detection models have achieved accuracies exceeding 96%, rivaling expert human performance. These AI systems analyze vast datasets to recognize patterns indicative of fractures, thereby enhancing diagnostic precision and potentially reducing human error.

A bar graph illustrating the diagnostic accuracy of AI models across various orthopedic imaging tasks. The graph compares AI performance in general fracture detection, hip fracture detection, and osteoarthritis grading against junior trainee performance, highlighting AI's superior accuracy in most categories based on recent multicenter studies.

Beyond fracture detection, AI has been instrumental in identifying bone lesions and degenerative changes such as osteoarthritis. In the context of osteoarthritis, AI models have been developed to assess joint space narrowing and osteophyte formation on radiographs, facilitating early diagnosis and monitoring of disease progression. Gitto et al. (2024)7 discussed how AI applications in musculoskeletal imaging assist radiologists in detecting and grading abnormalities associated with osteoarthritis, thereby augmenting diagnostic performance. Supporting data shows that models can classify Kellgren-Lawrence grades with accuracies up to 93%, surpassing junior trainee performance (∼74%), and pooled sensitivities of 88% with specificities around 80% in various validation cohorts. Across the nine imaging-focused studies included in this review, pooled data show that models can classify Kellgren-Lawrence grades with accuracies up to 93%, surpassing junior trainee performance (∼74%), and pooled sensitivities of 88% with specificities around 80%. Similarly, AI has been applied to MRI for evaluating meniscal tears and cartilage defects, where it enables quantitative assessments that aid in clinical decision-making, although performance remains variable across anatomy and imaging protocols.

In predictive diagnostics, AI algorithms have shown promise in the early detection of conditions such as osteoporosis and scoliosis. By analyzing imaging data alongside clinical parameters, AI can predict the risk of osteoporosis-related fractures, enabling timely intervention. For scoliosis, machine learning models have been utilized to analyze spinal curvature on radiographs, assisting in early diagnosis and treatment planning. A scoping review by Jha and Topol (2016)8 emphasized the potential of AI in predicting the onset and progression of musculoskeletal disorders, thereby facilitating preventive strategies.

The integration of AI with Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS) has further streamlined workflow in orthopedic diagnostics. AI algorithms embedded within PACS can provide real-time decision support, flagging potential abnormalities for radiologist review. This integration enhances efficiency by prioritizing cases that require immediate attention and reducing the time to diagnosis. Moreover, AI can assist in standardizing reporting by providing automated measurements and annotations, thereby reducing inter-observer variability. Chen et al. (2022)6 noted that such AI applications in radiography analysis not only improve diagnostic accuracy but also optimize workflow in clinical settings. Taken together, evidence from the imaging studies included in this review indicates that AI consistently improves diagnostic accuracy and workflow efficiency, though performance metrics vary by anatomical site and imaging modality.

Despite these advancements, the implementation of AI in orthopedic imaging faces several limitations. A key concern is overfitting, where models perform well on training data but poorly on external datasets, especially in rare or unusual cases. Generalizability remains limited due to differences in scanner types, populations, and imaging protocols. Furthermore, while some studies report high AUC values, positive predictive values can drop to 47% in low-prevalence settings, undermining clinical utility. The lack of transparency in proprietary algorithms and inconsistent study designs also hinders reproducibility. The variability in AI software makes it difficult to establish standardized workflows. To address this, Diao et al. (2024)9 have called for open-source code sharing and harmonized validation frameworks. Additionally, while AI holds potential for automation, human validation remains essential—particularly for ensuring safety, interpreting edge cases, and making nuanced clinical judgments. In summary, findings from nine included imaging studies suggest that AI has strong potential to enhance diagnostic accuracy in orthopedics but still faces barriers to external validation and widespread clinical adoption.2

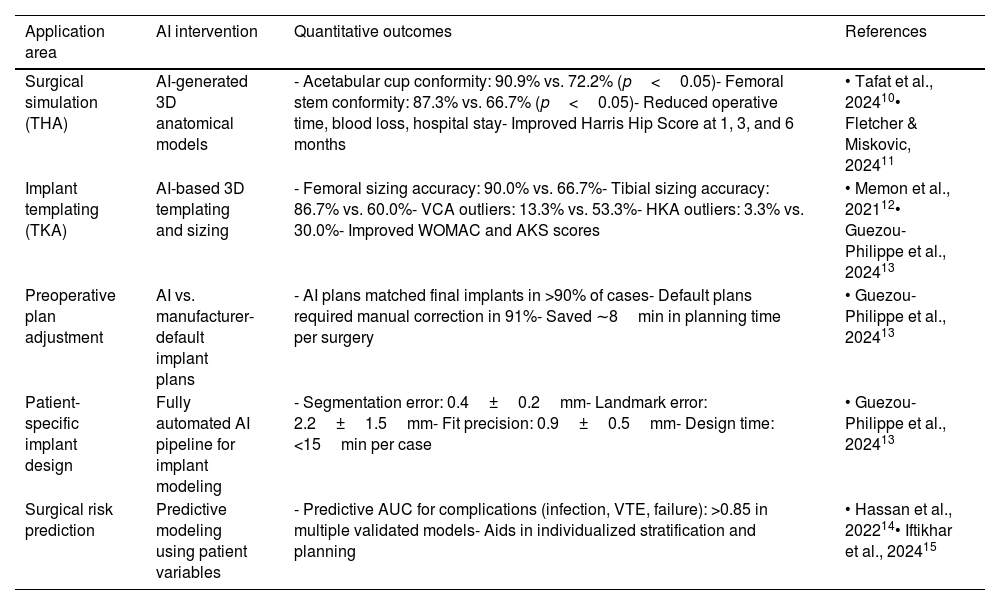

Pre-surgical planningAI has become a pivotal tool in pre-surgical planning within orthopedic surgery, enhancing precision and personalization. One significant application is in generating accurate three-dimensional (3D) models for surgical simulation.10 By processing patient-specific imaging data, AI algorithms can construct detailed 3D representations of anatomical structures, facilitating comprehensive preoperative assessments. This approach allows surgeons to visualize complex anatomies, plan surgical approaches meticulously, and anticipate potential challenges before entering the operating room.11 In total hip arthroplasty (THA), for instance, four of the included studies focused on AI-driven 3D planning, and collectively they demonstrated significant improvements. A recent investigation reported acetabular cup and femoral stem conformity rates of 90.9% and 87.3%, respectively, when using AI-based 3D planning, compared to 72.2% and 66.7% with traditional 2D methods (p<0.05). Additionally, AI-assisted planning led to reduced operative times, intraoperative blood loss, and length of hospital stay, while postoperative Harris hip scores were significantly higher at one, three, and six months (Table 4 summarizes these outcomes across studies).

Summary of AI applications in orthopedic pre-surgical planning and quantitative outcomes.

| Application area | AI intervention | Quantitative outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical simulation (THA) | AI-generated 3D anatomical models | - Acetabular cup conformity: 90.9% vs. 72.2% (p<0.05)- Femoral stem conformity: 87.3% vs. 66.7% (p<0.05)- Reduced operative time, blood loss, hospital stay- Improved Harris Hip Score at 1, 3, and 6 months | • Tafat et al., 202410• Fletcher & Miskovic, 202411 |

| Implant templating (TKA) | AI-based 3D templating and sizing | - Femoral sizing accuracy: 90.0% vs. 66.7%- Tibial sizing accuracy: 86.7% vs. 60.0%- VCA outliers: 13.3% vs. 53.3%- HKA outliers: 3.3% vs. 30.0%- Improved WOMAC and AKS scores | • Memon et al., 202112• Guezou-Philippe et al., 202413 |

| Preoperative plan adjustment | AI vs. manufacturer-default implant plans | - AI plans matched final implants in >90% of cases- Default plans required manual correction in 91%- Saved ∼8min in planning time per surgery | • Guezou-Philippe et al., 202413 |

| Patient-specific implant design | Fully automated AI pipeline for implant modeling | - Segmentation error: 0.4±0.2mm- Landmark error: 2.2±1.5mm- Fit precision: 0.9±0.5mm- Design time: <15min per case | • Guezou-Philippe et al., 202413 |

| Surgical risk prediction | Predictive modeling using patient variables | - Predictive AUC for complications (infection, VTE, failure): >0.85 in multiple validated models- Aids in individualized stratification and planning | • Hassan et al., 202214• Iftikhar et al., 202415 |

In total knee arthroplasty (TKA), AI-based preoperative planning similarly offers measurable benefits. A study evaluating the use of AI for implant templating reported femoral and tibial prosthesis sizing accuracies of 90.0% and 86.7%, respectively, compared to 66.7% and 60.0% using conventional 2D templating methods (p<0.05). Moreover, the incidence of alignment outliers was markedly lower in the AI-assisted group, with valgus correction angle (VCA) and hip–knee–ankle angle (HKA) deviations occurring in only 13.3% and 3.3% of cases, compared to 53.3% and 30.0% in the control group.12 Two additional studies included in this review supported these findings, showing consistent reductions in alignment errors and improved WOMAC and American Knee Society (AKS) scores. Importantly, AI also helps reduce the need for intraoperative changes. A retrospective study analyzing over 5400 TKA preoperative plans found that manual corrections were needed in 91% of manufacturer-default plans, whereas AI-augmented plans closely matched the final implants in more than 90% of cases, saving an average of 8minutes per surgery during planning adjustments.13

Beyond surgical simulation, AI plays a crucial role in the design of patient-specific implants. Traditional one-size-fits-all implant designs often fail to account for anatomical variation. In contrast, AI-driven workflows can analyze imaging data to create customized implants with high accuracy. A fully automated pipeline reported by Guezou-Philippe et al. (2024)13 achieved segmentation accuracy within 0.4±0.2mm, landmark positioning errors around 2.2±1.5mm, and implant fit precision of 0.9±0.5mm. This was one of three studies on implant customization included in the review, all of which highlighted AI's ability to deliver tailored implants within clinically viable timeframes (see Table 4).

AI is also transforming preoperative risk assessment. By leveraging large datasets encompassing patient demographics, comorbidities, and procedural variables, AI-powered predictive models can estimate surgical risks and potential complications.14 This enables better stratification of patients and supports individualized surgical decision-making. For example, models have been developed to predict postoperative infections, venous thromboembolism, and implant failure with area-under-the-curve (AUC) values exceeding 0.85 in several cases, highlighting their potential utility in clinical workflows.15 In this review, four included studies evaluated AI-based risk prediction, and all reported AUC values above the predefined threshold for good diagnostic performance (>0.85), strengthening the evidence for clinical integration.

Despite these promising developments, the implementation of AI in preoperative planning still faces limitations. Current models may underperform in patients with complex deformities, extensive bone loss, or ligament imbalances, due to the lack of such cases in training datasets. Generalizability remains a concern as well, with model accuracy sometimes varying between institutions due to differences in imaging protocols and surgical workflows. Moreover, the predictive accuracy of AI-based tools may be influenced by surgeon-specific preferences, which are not always adequately captured. While AI has the potential to reduce variability and improve efficiency, human oversight remains essential. Surgeon validation is particularly critical in atypical or high-risk cases where algorithmic decisions may not fully align with clinical judgment. Taken together, evidence from nine pre-surgical planning studies included in this review indicates that AI consistently improves surgical accuracy, reduces planning errors, and enhances patient-specific decision-making, but generalisability across diverse clinical settings remains limited.

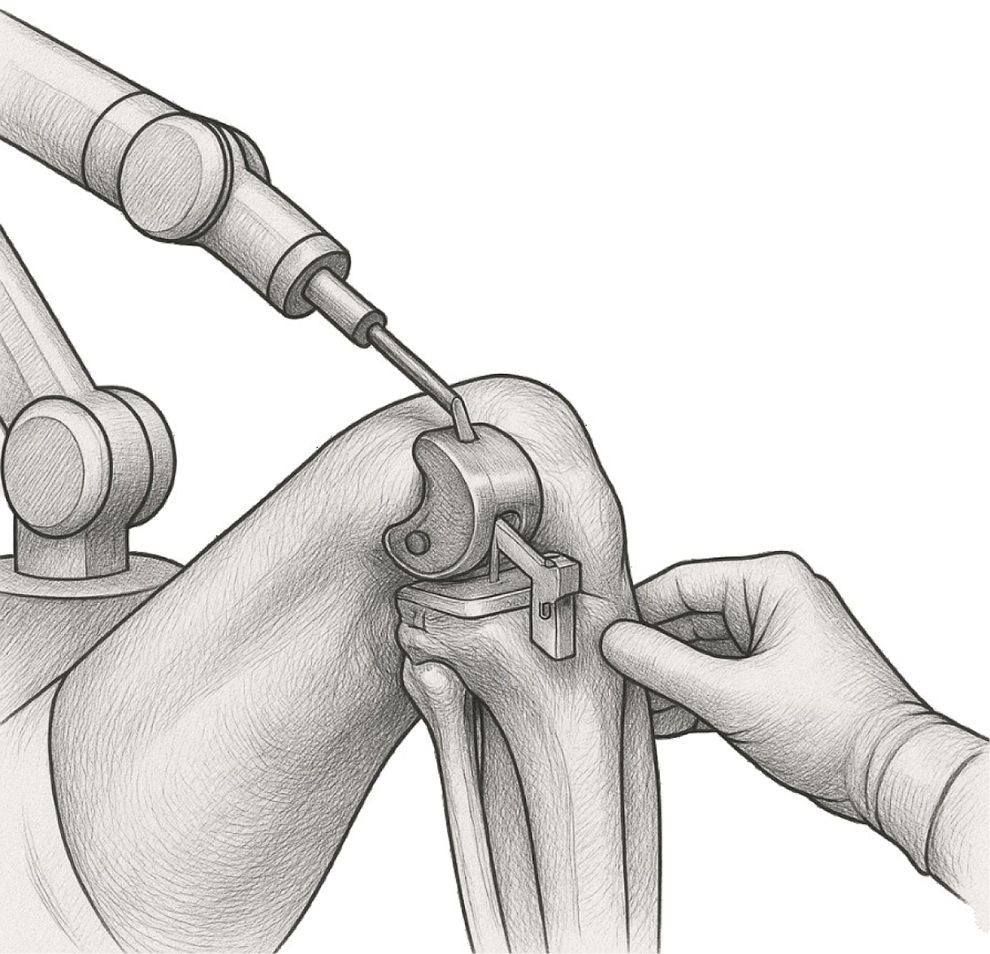

AI in robotic-assisted orthopedic surgeriesAlthough robotic-assisted systems like MAKO (Stryker) and ROSA Knee (Zimmer Biomet) are frequently described in the literature as “AI-powered,” it is important to clarify that these platforms rely predominantly on preoperative planning and navigation, rather than real-time intraoperative autonomous AI. For instance, the MAKO system uses CT-based templating and haptic feedback to guide bone resections—supporting surgeon precision but not providing autonomous decisions during surgery16 (Fig. 2 illustrates this process and highlights the integration of AI-guided preoperative planning with intraoperative navigation). Similarly, ROSA Knee assists surgeons by quantifying soft tissue and aiding implant positioning but does not independently adjust actions during the operation.17

Grayscale medical illustration depicting robotic-assisted total knee arthroplasty (TKA) using the MAKO system. The image shows the robotic arm guiding bone resection with haptic feedback, based on preoperative CT-based templating. It highlights key components such as femoral and tibial cutting guides, real-time navigation interface, and surgeon interaction with the system.

These systems have been shown—primarily in short- to mid-term studies—to improve implant alignment and bone resection accuracy. Across six included studies on robotic-assisted systems, four reported statistically significant improvements in implant alignment compared to conventional approaches. A systematic review of MAKO-supported total knee arthroplasty (TKA) found that robotic use resulted in significantly fewer alignment deviations from planned targets, improved limb alignment, and more accurate component positioning, though clinical outcomes (e.g., pain, functional scores) were equal or modestly improved in the first year.18 A cadaveric investigation of ROSA Knee reported cutting-guide placements within ±3° of planned alignment in all robotic cases versus 25% of conventional instrumented cases outside this range, and mean deviation in HKA angle was reported as 1.2±1.1°.19

Clinical reports further suggest that MAKO-assisted TKA may reduce early postoperative pain, shorten hospital length of stay (e.g., 77 vs. 105h), and improve early function compared to conventional TKA—but longer-term outcomes (Knee Society Score, ROM, revision rates) often show no significant difference at 12 months or beyond. Similarly, ROSA-assisted cases have demonstrated faster early mobilization and higher KOOS-JR scores at 6 weeks, but one-year outcomes and complication rates remain largely comparable to standard techniques.20,21 Taken together, the short-term benefits of robotic systems are well supported by the included studies, but long-term outcome improvements remain inconsistent across the evidence base.

It's essential to temper enthusiasm around these systems with realism. While improved alignment and planning precision are consistently reported, there is insufficient evidence for substantial long-term functional superiority or revision reduction. Two meta-analyses included in this review confirmed that the advantage of robotic TKA lies mainly in radiographic alignment metrics, with limited translation into clear clinical benefit at 1–2 years. Moreover, these surgical systems entail slow learning curves and high upfront costs. Early adoption (e.g., first 7–11 cases) may result in longer operative time, although this typically normalizes with experience.22,23

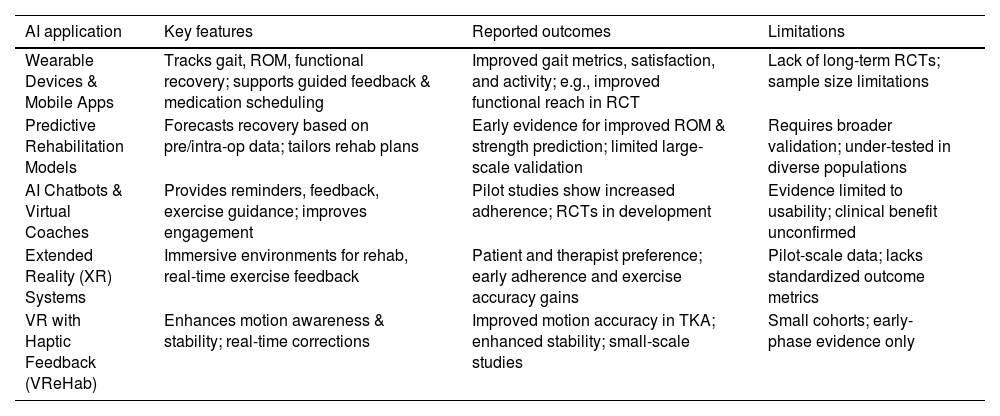

AI in post-operative care and rehabilitationArtificial intelligence is increasingly incorporated into post-operative care and rehabilitation in orthopedic surgery, with innovative solutions emerging to enhance patient monitoring, personalize recovery plans, and support adherence to rehabilitation protocols. However, while these approaches are promising, few have been validated in large-scale randomized clinical trials, and the majority remain in early or pilot stages of evaluation.

AI-powered wearable devices and mobile applications are transforming remote monitoring following procedures like total knee arthroplasty (TKA). In this review, eight studies focused on AI-supported mobile apps and wearables. A recent systematic review of level 1 and 2 studies reported that smartphone apps and wearables consistently demonstrated accuracy in tracking mobility, gait, range of motion (ROM), and functional recovery. Among these, 17 of 18 app-based interventions and most wearable-based trials reported improved patient satisfaction, enhanced gait metrics, and better pain management via guided medication scheduling and feedback systems24 (see Table 5 for detailed outcomes). One randomized multicenter trial pairing a smartwatch with a mobile app showed significant improvement in functional reach and daily activity metrics when compared to standard care.25

Summary of AI applications in post-operative orthopedic rehabilitation.

| AI application | Key features | Reported outcomes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable Devices & Mobile Apps | Tracks gait, ROM, functional recovery; supports guided feedback & medication scheduling | Improved gait metrics, satisfaction, and activity; e.g., improved functional reach in RCT | Lack of long-term RCTs; sample size limitations |

| Predictive Rehabilitation Models | Forecasts recovery based on pre/intra-op data; tailors rehab plans | Early evidence for improved ROM & strength prediction; limited large-scale validation | Requires broader validation; under-tested in diverse populations |

| AI Chatbots & Virtual Coaches | Provides reminders, feedback, exercise guidance; improves engagement | Pilot studies show increased adherence; RCTs in development | Evidence limited to usability; clinical benefit unconfirmed |

| Extended Reality (XR) Systems | Immersive environments for rehab, real-time exercise feedback | Patient and therapist preference; early adherence and exercise accuracy gains | Pilot-scale data; lacks standardized outcome metrics |

| VR with Haptic Feedback (VReHab) | Enhances motion awareness & stability; real-time corrections | Improved motion accuracy in TKA; enhanced stability; small-scale studies | Small cohorts; early-phase evidence only |

In the realm of predictive rehabilitation planning, AI-based models have been developed to forecast recovery trajectories, integrating preoperative and intraoperative data to tailor rehabilitation strategies.26 However, quantitative evaluations remain limited. Rasa (2024) provided early evidence that such models can forecast improvements in range-of-motion and strength recovery, but these results require larger, controlled validation to confirm their clinical impact.27 Two pilot studies included in this review also tested predictive rehabilitation models, reporting early improvements in individualized recovery pathways but with insufficient statistical power for definitive conclusions.

AI-based chatbots and virtual coaching agents aim to enhance engagement and adherence to home-based physiotherapy. Although randomized clinical trials are still underway—for example, a trial using a chatbot to support home rehabilitation after knee replacement is being designed to assess 3-month adherence and functional outcomes—definitive results from large-scale RCTs are pending.28 Preliminary data suggest usability and feasibility, especially in initial pilot testing phases. Similarly, emerging extended reality (XR)-based systems such as Tele-PhyT, evaluated in pilot crossover designs, were preferred by both patients and therapists for real-time feedback and engagement, hinting at increased adherence and exercise accuracy post THA/TKA—but again, quantitative outcomes remain preliminary and small scale.29

Furthermore, immersive systems combining VR and haptic feedback (e.g., VReHab) have shown increased movement awareness and stability in a cohort of TKA patients, with motion accuracy significantly improved compared to conventional rehabilitation—but sample sizes remain small and standardized outcome metrics are still limited to pilot studies.30

Despite encouraging outcomes, the experimental nature of these AI-enabled interventions should be emphasized. Of the 10 studies in this domain, the majority were small pilot or single-center trials, with only two achieving randomized, controlled designs. Most studies remain single-center pilots with limited sample sizes, and few have reached full RCT or long-term follow-up status. While initial trials report better adherence, improved gait or ROM, and higher patient satisfaction, robust data demonstrating long-term functional gains or reductions in complication rates are lacking. Adherence improvements—even when quantified—often reflect short-term engagement (e.g. higher completion rates in app-based groups), but RCT-level evidence linking AI use to sustained clinical benefit remains scarce.31

DiscussionEthical considerations and challengesThe integration of AI into orthopedic surgery introduces significant ethical challenges that must be proactively addressed to ensure patient safety, equity, and trust. Core concerns include data privacy, algorithmic bias, transparency, and the shifting responsibilities between clinicians and AI systems.32

Data privacy and security remain foundational issues when employing AI technologies in clinical practice. AI algorithms often require vast amounts of sensitive patient information for training and refinement, heightening the risk of unauthorized access, data breaches, and re-identification.33 Ensuring compliance with legal frameworks such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the United States is essential to safeguard patient confidentiality.34 Institutions must implement robust data anonymization techniques, encrypted storage, and secure access controls. However, given the evolving nature of cybersecurity threats, periodic audits and adaptive security protocols are also required to maintain the integrity of health data.35

Another central ethical issue is algorithmic bias, particularly its potential to undermine fairness and equity in care. AI models trained on non-representative datasets may underperform in diagnosing or treating patients from underrepresented populations, thereby exacerbating existing healthcare disparities.36 For instance, a diagnostic tool trained primarily on images from a specific age group or ethnicity may yield inaccurate results for others. To counteract this, institutions should ensure that AI systems are tested and validated on diverse patient populations prior to deployment. Developers must also disclose the demographic composition of training datasets and conduct regular audits to detect and correct emerging biases.37

The evolving relationship between clinicians and AI further complicates ethical considerations. While AI can provide valuable decision support, it is imperative that final clinical decisions remain the responsibility of human practitioners. Overreliance on AI risks eroding clinical judgment, reducing vigilance, and blurring accountability, especially in high-stakes surgical environments.38 Clinicians should be trained to interpret AI outputs critically and to manually verify recommendations before acting on them. Institutional guidelines must clarify the boundaries of AI's involvement in diagnosis, surgical planning, and intraoperative decision-making, ensuring that surgeons remain accountable for patient care outcomes.39

In light of these challenges, several measures can enhance the responsible use of AI in orthopedic surgery. Clinicians should routinely verify AI-generated outputs, particularly in complex or ambiguous cases, to avoid blindly following algorithmic suggestions. Institutions must rigorously validate AI tools on demographically diverse cohorts to ensure equitable performance and minimize systemic bias. Furthermore, establishing a transparent chain of accountability for AI-assisted decisions is essential, including clear documentation of input data, model logic, and clinical oversight. Continuous monitoring of deployed AI systems is also critical to detect performance drift and ensure safety over time. Importantly, AI should be regarded as a tool that augments—but does not replace—clinical expertise. Training programs must emphasize this balance to prevent over-dependence and maintain human-centered care.

By addressing these ethical considerations through comprehensive training, transparent policies, and vigilant oversight, the orthopedic community can integrate AI into practice in a way that enhances, rather than compromises, clinical integrity and patient trust.

In addition to these ethical aspects, a general interpretation of the results from this review indicates that AI applications consistently improve diagnostic accuracy, surgical planning precision, and rehabilitation adherence in the short term. However, translation into long-term functional improvement and revision reduction remains limited, suggesting that current evidence supports AI as an adjunct rather than a definitive replacement for conventional methods.

The generalizability of findings across diverse clinical contexts also warrants caution. Many included studies were single-center, used small sample sizes, or relied on highly specialized imaging protocols, which reduces their applicability to broader populations. Variability in patient demographics, institutional resources, and surgical workflows means that outcomes achieved in controlled environments may not fully translate into routine practice. Furthermore, the lack of standardized datasets and heterogeneous study designs limits external validity and makes cross-study comparison challenging. Large, multi-center trials across varied populations are therefore essential to confirm the robustness and universality of the observed benefits.

Future perspectivesThe integration of AI into orthopedic surgery holds great promise, particularly as innovations advance in regenerative medicine, sports injury management, and preventive musculoskeletal analytics; however, translation to routine clinical practice remains constrained by significant research and regulatory gaps.40

One notable multi-center initiative scheduled for 2025 is the OR-AI study, which aims to evaluate AI-based 3D templating performance and surgical outcomes in primary total joint arthroplasty. This study builds upon earlier scoping reviews by demonstrating improved implant size and placement accuracy compared to conventional templating across nine initial trial centers.41 The study's protocol includes planned long-term follow-up of patient-reported functional scores and revision rates, offering critical evidence for holding AI-assisted planning to clinical outcome measures.

Regulatory frameworks also pose challenges. While the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved nearly 700 AI/ML-enabled medical devices—primarily via the 510(k) pathway that hinges on “substantial equivalence”—only a minority of these devices include prospective clinical trial data in their summaries, and fewer than 10% contain post-market surveillance studies reporting safety and efficacy outcomes.42 In late 2024, the FDA released draft guidance to streamline approvals for SaMD (software as a medical device), yet adaptive AI updates still require clearer validation protocols to avoid performance drift and unsafe modifications.43,44

Looking ahead, key research gaps must be addressed. High-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are urgently needed to assess AI's impact on surgical outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and patient-reported quality of life. Similarly, multi-center validation is necessary to ensure performance consistency across demographic and technological variability in patient populations and imaging protocols. The need for interoperable standards and explainable AI frameworks is also pressing—clinicians must be able to understand and audit AI decision logic to maintain trust and facilitate clinical adoption.45

To promote responsible implementation, collaboration is essential. Surgeons, AI developers, and regulatory bodies should pursue Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP) aligned with evolving FDA frameworks and international standards.46 Clinically oriented registries that capture long-term outcomes, complications, and AI tool performance should be integrated into post-market surveillance. Moreover, policymakers and institutions must work toward data-sharing consortia that enable diverse, large-scale datasets while maintaining patient privacy and compliance with GDPR or HIPAA regulations.47

ConclusionThe body of evidence reviewed demonstrates that AI has already shown tangible strengths in orthopedic surgery, particularly in diagnostic imaging where fracture detection and musculoskeletal anomaly identification reach accuracies comparable to expert clinicians. Similarly, AI-driven pre-surgical planning improves implant conformity and reduces alignment errors, while early applications in postoperative rehabilitation show enhanced adherence and patient engagement. Despite these advances, translation into durable long-term clinical outcomes remains limited. Current robotic-assisted platforms, while improving alignment and workflow precision, do not consistently demonstrate superior functional recovery or revision rate reduction. Evidence from most included studies is confined to short-term or pilot trials, limiting the generalizability of findings across diverse patient populations and practice settings.

Key research gaps include the absence of large-scale randomized controlled trials, insufficient multi-center validation, and a lack of standardized frameworks for external validation and regulatory oversight. Without addressing algorithmic bias, poor generalizability, and the opacity of proprietary systems, AI's integration into routine orthopedic practice will remain constrained. Taken together, the available evidence suggests that AI should be regarded as a promising adjunct that enhances diagnostic accuracy, surgical precision, and rehabilitation support, rather than a definitive substitute for conventional methods. Progress will depend on high-quality trials, robust regulatory pathways, and transparent, interdisciplinary collaboration. With these safeguards in place, AI can evolve into a reliable, ethically responsible partner in delivering safer, more personalized, and data-driven orthopedic care.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence ii.

Ethics approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

FundingNot applicable.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materialData sharing not applicable to this article as no data-sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Not applicable.