Most foot surgeons recognize the difficulties to define each patient's hallux valgus (HV) deformity and to select the most appropriate surgical treatment to achieve the best long term outcome. The goal of this study was to analyze radiologic outcomes after distal chevron metatarsal osteotomy and to identify specific preoperative radiological parameters correlating with radiological recurrence.

Materials and methodsOne hundred twenty patients (134 feet) in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe HV deformity who underwent distal chevron metatarsal osteotomy at our hospital between 2014 and 2019 were included in the present study. Each patient was evaluated preoperatively, postoperatively and at final follow-up by means of radiographs lateral and dorsoplantar views. We examined fourteen radiographic measurements. Data were collected retrospectively.

ResultsThe mean follow-up time was 23.65 months (range 6–69.4 months). The recurrence rate was 76.1%. Radiologic HV recurrence was defined by a final hallux valgus angle (HVA) equal or greater than 20 degrees.

ConclusionsGreater age at time of surgical treatment and preoperative noncongruent I metatarsophalangeal joint were identified as predictors for HV recurrence.

Level of evidenceLevel IV.

La mayoría de los cirujanos de pie reconocen las dificultades para definir la deformidad en hallux valgus (HV) de cada paciente y para seleccionar el tratamiento quirúrgico más adecuado para lograr el mejor resultado a largo plazo. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar los resultados radiológicos tras una osteotomía metatarsiana distal en chevron e identificar los parámetros radiológicos preoperatorios específicos que se correlacionan con la recidiva radiológica.

Material y métodosCiento veinte pacientes (134 pies) con deformidad de HV moderada o severa sintomática en nuestro hospital entre 2014 y 2019 se incluyeron en el presente estudio. Cada paciente se evaluó preoperatoriamente, postoperatoriamente y al final del seguimiento mediante radiografías en proyecciones dorsoplantar y lateral. Se analizaron catorce medidas radiográficas. Los datos se recogieron retrospectivamente.

ResultadosEl tiempo medio de seguimiento fue de 23,65 meses (rango 6-69,4 meses). La tasa de recidiva fue del 76,1%. Recidiva de HV radiológica se definió como un ángulo de HV final igual o mayor a 20 grados.

ConclusionesMayor edad en el momento del tratamiento quirúrgico y una articulación metatarsofalángica del primer dedo no congruente preoperatoriamente se identificaron como predictores de recidiva de HV.

Nivel de evidenciaNivel IV.

Hallux valgus (HV) deformity has been one of the most studied pathologies of the foot due to its high frequency and symptomatology.

It is a progressive triplanar deformity: the first metatarsal adducts, dorsiflexes, and pronates.

Most foot surgeons recognize the difficulties to define each patient's HV deformity and to select the most appropriate surgical treatment to achieve the best long term outcome.

Which surgical procedure achieve the best outcome is still controversial. Preoperative evaluation of the radiographs is fundamental to select the correct surgical treatment.

Distal metatarsal chevron osteotomy is widely accepted for correction of HV.1,2 Combining the osteotomy with lateral soft tissue release and Akin proximal phalangeal osteotomy extends its indications to include moderate to severe HV deformities, in addition to the mild to moderate HV for which it had first been indicated.

Additionally, distal chevron metatarsal osteotomy (DCMO) was demonstrated to be appropriate for aged 60 years or older patients.3

Recurrence is the most common complication following HV surgery correction, which can occur after any surgical technique.4 In a meta-analysis Ezzatvar et al. found that prevalence of HV recurrence was 24.86%.5

Controversies remain regarding the preoperative radiological predictors for recurrence after surgical correction HV deformity. Many radiological factors have been considered predictors of recurrence after HV surgical treatment. Only 2 or 3 factors were analyzed in each of other studies.

The goal of this study was to analyze radiologic outcomes after DCMO and to identify specific preoperative radiological parameters correlating with radiological recurrence in patients with symptomatic moderate to severe HV deformity.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the institutional ethics committee (23/081). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

One hundred twenty patients (134 feet) with symptomatic, unilateral moderate to severe HV who underwent DCMO at our institution between January 2014 and December 2019 were included in this study.

Radiological data were collected retrospectively.

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- (1)

HV patients with hallux valgus angle (HVA) equal or more than 20°,

- (2)

age at surgery older than 18 years to exclude juvenile hallux deformity,

- (3)

failed previous of nonoperative management,

- (4)

non surgical procedures on the minor rays and

- (5)

post-operation follow-up time being more than 6 months.

Patients were excluded if one of these conditions was present:

- (1)

radiographic evidence of significant degenerative arthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP),

- (2)

rheumatoid arthritis affecting the foot,

- (3)

foot infection, neuromuscular disease, or peripheral vascular disease,

- (4)

previous forefoot surgery, or

- (5)

incomplete radiographs preoperatively, postoperatively and at the final follow-up.

A tourniquet was used in all patients. A straight incision of approximately 4–5cm was made on the medial surface of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint.

A midline capsulotomy was performed in line with the skin incision.

A medial exostosis resection was undertaken to the sagittal sulcus with a saw.

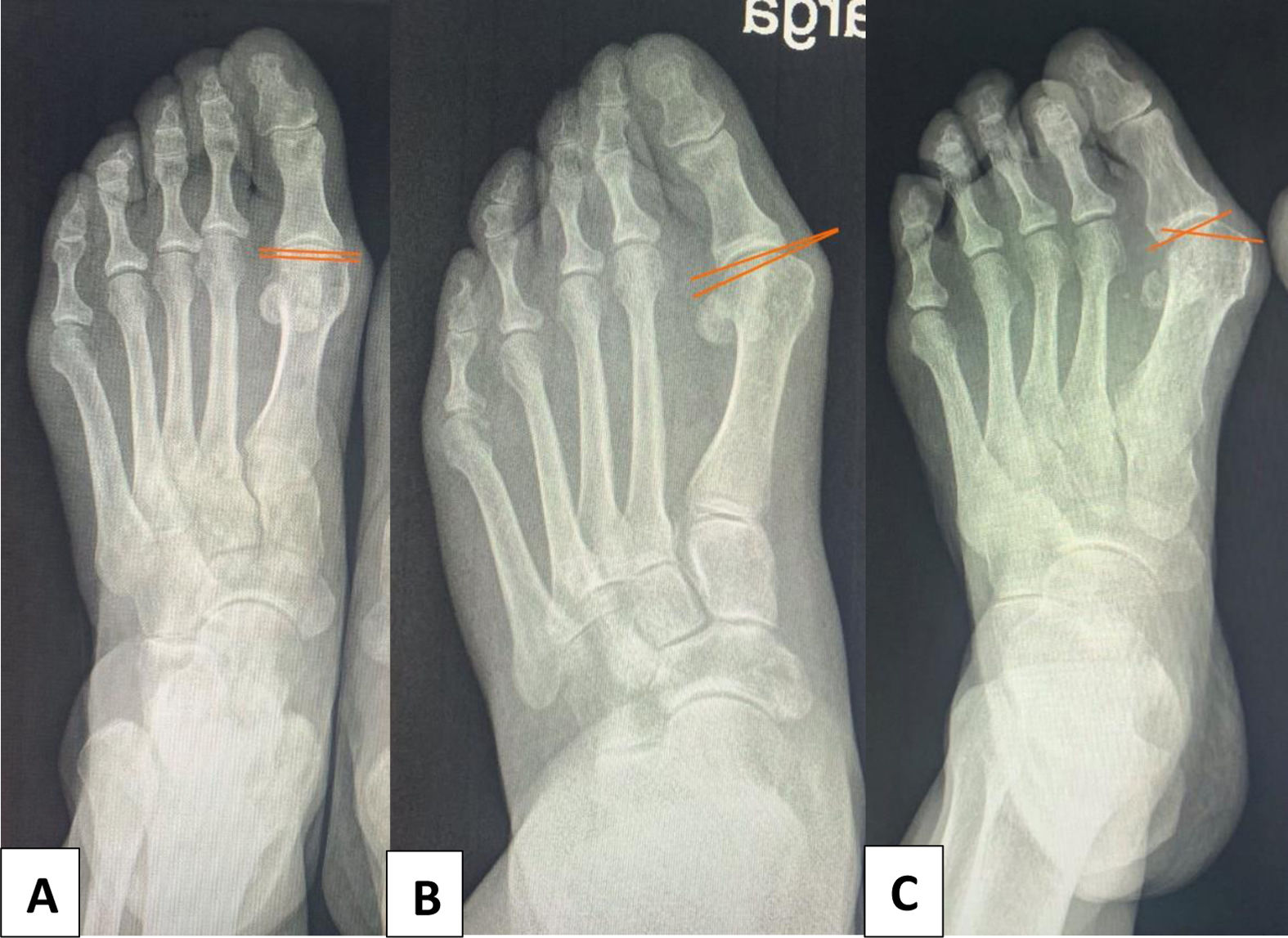

Osteotomy centered at the head was subsequently made. The dorsal cut was directed perpendicular to the second metatarsal in the axial plane. The length of the plantar cut could be adjusted according to the IMA angle (traditional chevron or more horizontal, extended plantar limb). The plantar cut was directed slightly plantar in the medial to lateral direction. For large distal metatarsal articular angle (DMAA) the procedure included the removal of a medially-based wedge (Fig. 1).

The metatarsal head was displaced according to the deformity and the width of the first metatarsal. The osteotomy was secured with one or two cannulated screws sized 2.5 or 3.0mm, depending on the length of the osteotomy, from the dorsal shaft to the plantar metatarsal head.

A lateral soft tissue release procedure and an additional Akin osteotomy were performed depending on the operating surgeon's judgment.

Intraoperative confirmation that the first metatarsal head is repositioned over the sesamoids was checked by simulating weight bearing on a flat surface and X-ray fluoroscopy. Finally, medial capsular plication was performed to restore the corrected alignment of the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

Postoperative careWeight bearing with a hard-sole orthopedic shoe was permitted as tolerated the day after surgery. After 6 weeks, full weight bearing and sports shoe were permitted. We recommend a toe spacer for at least 3 months postoperatively to decrease the tension on the medial side.

Radiographic assessmentWeight bearing foot dorsoplantar and lateral radiographs were obtained preoperatively, and final follow-up.

Anteroposterior and oblique radiographs were taken immediately after the operation without weight bearing.6

In the dorsoplantar radiograph the factors evaluated included: first-second intermetatarsal angle (I–II IMA), HV angle (HVA) (Fig. 1), proximal to distal phalangeal articular angle (PDPAA), tibial sesamoid position (TSP), distal metatarsal articular angle (DMAA), first metatarsophalangeal joint congruence (Fig. 2), shape of the lateral edge of the first metatarsal head, length of first ray (EL), metatarsus adductus angle (MAA) and talonavicular coverage angle (TNCA). In the lateral radiograph we investigate: talo-first metatarsal angle or Meary’ angle (TIMA), calcaneal pitch angle (CPA), first metatarsal inclination angle and plantar gapping of the first tarsometatarsal joint (PG).

Three orthopaedic surgeons measured all radiographic parameters.

To define the longitudinal axis of the first metatarsal a line is drawn from the centre of the head through the centre of the base, as described by Miller in 1974.7

Mann and Coughlin classified HV into three types according to the HVA and the I–II IMA: mild (<20°, <11°), moderate (20–40°, 11–16°) and severe (>40°, >16°).8

Tibial sesamoid position (TSP) was determined according method documented by Smith et al.9

The excessive length of the first ray (EL) was calculated using the equation EL=P1−P2−D (P1, length of the great toe, P2, length of the second toe, and D, metatarsal protrusion distance).10

Radiographically, first ray instability was defined as plantar gapping of the first TMT or subluxation of the first metatarsal relative to the medial cuneiform on the lateral radiograph.

Radiologic HV recurrence was defined by a final HVA equal or greater than 20 degrees.

Statistical analysisRecurrence was the dependent variable which was analysed using variables of the data base as explanatory variables. The results were reported as odds ratio for recurrence (OR) with 95% CI. Differences with a P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Recurrence was analysed in a univariate way using a logistic regression with one explanatory variable.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses determined prediction ability of proposed multivariate models. Model selection was done under minimum AIC criteria.

Statistical computations were done in R under RStudio, with the following packages, ROCR and ggplot2.

ResultsOnly 7 (5.22%) of those patients were men, while 127 (94.78%) were female. The mean age of the patients at the time of surgery was 62.95 years (range 26–88). The mean follow-up was 23.65 months (range 6–69.4).

Out of the 134 cases of HV, 89 (66.42%) and 45 (33.58%) were classified as moderate and severe, respectively (Table 1).

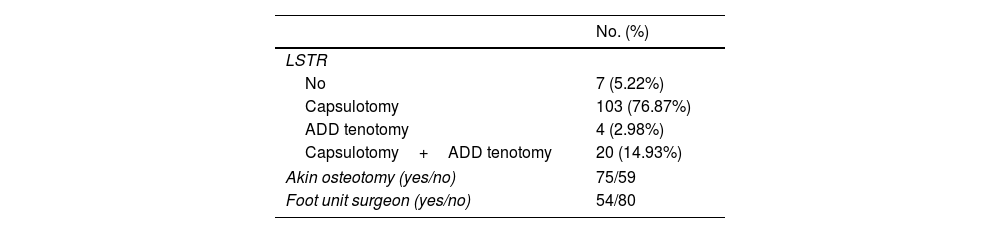

A lateral soft tissue release (LSTR) procedure was applied in 127 cases (94.78%) and included lateral joint capsule split (81.10%), adductor tenotomy (3.15%) or capsulotomy with adductor tenotomy (15.75%).

An additional Akin was performed in 75 (55.97%) (Table 2).

All patients presented a HVA less than 12 degrees in anteroposterior radiograph immediately after the operation without weight bearing.

Recurrence was reported in 102 cases (76.1%) over a mean follow-up period of 23.65 months (range 6–69.4).

Comparisons between baseline and follow-up values are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Radiographic parameters of the series. Weight bearing foot dorsoplantar radiograph.

| Preoperative | Final follow-up | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I–II IMA (degrees) | 12.96 | 10.13 | 0.000 |

| HVA (degrees) | 37.55 | 25.96 | 0.000 |

| PDPAA (degrees) | 7.16 | 8.10 | 0.136 |

| TSP | |||

| 0 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.004 |

| 1 | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 1.000 |

| 3 | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.000 |

| DMAA (degrees) | 17.05 | 14.81 | 0.054 |

| I MTP joint congruence | |||

| Congruent | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.001 |

| Deviated noncongruent | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.421 |

| Subluxate noncongruent | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.003 |

| Lateral edge I MTT head (type) | |||

| Angular | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.370 |

| Intermediate | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.005 |

| Round | 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.000 |

| EL | 8.31 | 6.78 | 0.023 |

| MAA (degrees) | 12.93 | 13.34 | 0.705 |

| TNCA (degrees) | 17.52 | 15.94 | 0.022 |

Abbreviations: I–II IMA, I–II intermetatarsal angle; HVA, hallux valgus angle; PDPAA, proximal to distal phalangeal articular angle; TSP, tibial sesamoid position; DMAA, distal metatarsal articular angle; MTP, metatarsophalangeal; MTT, metatarsal; EL, excessive length of I ray; MAA, metatarsus adductus angle; TNCA, talonavicular coverage angle.

Radiographic parameters of the series. Weight bearing foot lateral radiograph.

| Preoperative | Final follow-up | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIMA (degrees) | 2.26 | 1.47 | 0.420 |

| CPA (degrees) | 20.29 | 19.70 | 0.347 |

| I MTT inclination angle (degrees) | 18.90 | 18.48 | 0.399 |

| PG (yes/no) | 0.08/0.92 | 0.07/0.93 | 0.816/0.816 |

Abbreviations: TIMA, talo-I metatarsal angle (Meary’ angle); CPA, calcaneal pitch angle; MTT, metatarsal; PG, plantar gapping of the I tarsometatarsal joint.

Using univariate logistic regression analysis, preoperative I MTP joint deviated (P=0.047, 95% CI 1.34–217.22) and subluxate noncongruent (P=0.025, 95% CI 1.80–259.72) and age at the time of surgery (P=0.009, 95% CI 1.02–1.11) showed significant association with recurrence (Table 5). Using multivariate analysis, preoperative I MTP joint subluxate noncongruent (P=0.000, 95% CI 2.423–21.406) and age at the time of surgery (P=0.007, 95% CI 1.019–1.119) showed significant association with recurrence.

Factors predicting hallux valgus recurrence.

| P value* | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.009 | 1.06 | 1.02–1.11 |

| Preop HVA | 0.110 | 1.04 | 0.99–1.09 |

| Preop I–I IMA | 0.526 | 0.96 | 0.85–1.08 |

| Preop PDPAA | 0.621 | 0.98 | 0.91–1.06 |

| Preop TSP | |||

| 1 | – | – | – |

| 2 | 0.560 | 1.41 | 0.42–4.45 |

| 3 | 0.555 | 0.72 | 0.23–2.04 |

| Preop DMAA | 0.158 | 1.03 | 0.99–1.08 |

| Preop I MTP joint congruence | |||

| Deviated noncongruent | 0.047 | 10.40 | 1.34–217.22 |

| Subluxate noncongruent | 0.025 | 12.91 | 1.80–259.72 |

| Preop lateral edge I MTT head | |||

| Intermediate | 0.256 | 0.39 | 0.06–1.68 |

| Round | 0.229 | 0.38 | 0.06–1.54 |

| Preop EL | 0.119 | 1.06 | 0.99–1.15 |

| Preop MAA | 0.488 | 0.98 | 0.94–1.03 |

| Preop TNCA | 0.252 | 1.04 | 0.97–1.11 |

| Preop TIMA | 0.733 | 0.99 | 0.94–1.04 |

| Preop CPA | 0.474 | 0.97 | 0.90–1.05 |

| Preop I MTT inclination angle | 0.394 | 0.95 | 0.86–1.06 |

| Preop PG | 0.975 | 0.98 | 0.26–4.66 |

| Follow-up | 0.431 | 1.0 | 1.00–1.00 |

Abbreviations: HVA, hallux valgus angle; I–II IMA, I–II intermetatarsal angle; PDPAA, proximal to distal phalangeal articular angle; TSP, tibial sesamoid position; DMAA, distal metatarsal articular angle; MTP, metatarsophalangeal; MTT, metatarsal; EL, excessive length of I ray; MAA, metatarsus adductus angle; TNCA, talonavicular coverage angle; TIMA, talo-I metatarsal angle (Meary’ angle); CPA, calcaneal pitch angle; PG, plantar gapping of the I tarsometatarsal joint.

Different definitions of recurrence have been given in the literature: HVA equal or greater than 20 degrees,10–13 HVA greater than 20 degrees,14 HVA greater than 15 degrees,15,16 increase of HVA equal o more than 3 degrees during the follow-up17 and I–II IMA greater than 10 degrees.18 This reflects a lack of consensus to define a recurrence in HV. In our series, we defined recurrence as a final HVA equal or greater than 20 degrees.

On the other hand, in any HV outcome study it is important to clearly identify how the longitudinal axis of the first metatarsal was determined. In this study, to define the longitudinal axis of the first metatarsal a line is draw from the centre of the head through the centre of the base, as described by Miller in 1974.7

Publications have reported rate of recurrence as high as 73% following DCMO,16 which is unacceptably high. The recurrence rate in our study population was 76.1%.

In our cohort, preoperative I MTP joint deviated and subluxate noncongruent and a higher age at the time of surgery were significant correlated to recurrence after DMCO for HV.

In other studies, preoperative HVA and first-second IMA were found to be significant risk factors for HV recurrence.5 According to other authors only preoperative HVA was significantly associated with the recurrence of HV.13 Pentikainen et al. found that HV recurrence was significantly related to preoperative congruence, DMAA, tibial sesamoid position, HVA, and I–II IMA.16

Kaufmann et al. found a mean correction of 6.5 degrees of the IMA with the DCMO and, therefore, they do not recommend the DCMO for HV in cases exceeding a preoperative I–II IMA of 15.5 degrees.19

A foot surgeon should estimate amount of bony contact between the fragments after sliding the distal fragment laterally. The amount of displacement will depend on the width of the metatarsal head to be displaced, the distance where it can be shifted maximally and the removal of the bony prominence. Kiyak et al. described a method for predicting contact area percentage and, as a result, the stability after distal chevron osteotomy.20

The role of incongruence in the metatarsophalangeal joint in HV recurrent has been reported by previous authors in DCMO.16

Recently, more attention has been paid to first metatarsal internal malrotation (pronation) in HV in determining recurrence of the deformity.12,21 Okuda et al. showed how the first metatarsal pronation could be evaluated by the shape of the lateral edge of the first metatarsal head (round sing).12 Additionally, inclination of the first metatarsal in the sagittal plane affects the roundness of the first metatarsal head.22 The altered distal metatarsal articular angle (DMAA) spontaneously corrects after performing a coronal deformity correction.23 Distal chevron metatarsal osteotomy treats the metatarsus varus deviation, but not any rotation; hence, the undercorrection of the rotational component of the HV deformity could explain, at least in part, some cases of recurrence.

On the other hand, a degree of first metatarsal pronation exists in patients even without HV. A study in subjects who had no foot deformity showed that first metatarsal pronation occurs due to natural full weight bearing.24 Relation between the first metatarsal pronation due to natural full weight bearing and hallux valgus pathogenesis should be analyzed.

Aier et al. reported that metatarsus adductus (MA) increases the risk of radiographic recurrence of HV deformity (15.2% in patients without MA and 28.9% in those with MA).14 Except in cases of severe combined deformity, Lee et al. in a multicentre study recommend DCMO without any procedure for the other metatarsals with a recurrence rate relatively less (11.1%) than previously published literature.11 Definitely, the presence of MA adds complexity to the treatment of HV.25

Heyes et al. demonstrated that preoperative I–II HVA greater than 35 degrees was significantly associated with increased HV recurrence and that preoperative more severe the pes planus deformity, the higher the frequency of recurrence following scarf osteotomy.15 Thus, Choi et al. advocate correcting HV and hindfoot valgus simultaneously.26 Conversely, some investigators state that there is no significant correlation among the radiographic parameters of pes planus (talo-first metatarsal angle and calcaneal pitch measured on the weight bearing lateral radiographs and the talonavicular coverage angle measured on the weight bearing dorsoplantar radiographs) and the postoperative radiographic outcomes of HV surgery in adult patients.13

Instability of the first metatarsocuneiform joint as seen as a Meary's line disruption or plantar gapping of the first tarsometatarsal joint on the lateral foot weight bearing radiograph, is a risk factor for recurrence.18 In these cases, arthrodesis of the first metatarsocuneiform joint would be indicated.

Several studies have shown that lateral soft tissue release as an adjunct to DCMO may extend the indication of this osteotomy. In a meta-analysis Yammine et al. demonstrated a beneficial effect of lateral soft tissue release when associated to a DCMO.27 Controversy remains regarding which exact anatomical structures need to be released and the best surgical approach in combination with metatarsal osteotomies for adequate surgical correction.

Shibuya et al. stated that an additional Akin osteotomy for HV correction is of uncertain value.28 Recently Strydom et al. recommended the correction of HV interphalangeal deformity and established that its persistence may then be a predictor of recurrence of HV.29 A study concludes that a preoperative proximal to distal phalangeal articular angle above 8 degrees indicates the need to perform Akin osteotomy.30

Accordingly, in HV correction every aspect of the deformity should be addressed to reduce the risk for recurrence. Better understanding of pathogenesis of HV,31 right choice of the procedure and technical competence in performing the procedure are key for reducing the recurrence after HV surgery.

The present study has limitations in being a retrospective study, which led a risk of bias due to the lack of standardization in methodology and all patients were from a single center. It is a radiographic study only, we did not look at functional outcomes or patient satisfaction, and limited to a 2-dimensional cross-sectional analysis. Wide range of follow-up time may introduce variability in results.

ConclusionsPreoperative I MTP joint deviated and subluxate noncongruent were identified as predictors for HV recurrence. Patients who had recurrence of their deformity had a greater age at the time of surgery than those who maintained correction.

To know preoperative radiographic parameters resulting in recurrence would be advantageous for future improvement of outcome following HV surgery.

Surgeons could use these findings to select the best candidates for HV deformity treatment with DCMO.

Future studies are necessary to investigate if radiological recurrence of the deformity does imply a recurrence of pain and disability and how many patients underwent reoperation for symptomatic, recurrent HV.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical approvalInstitutional approval was obtained for this study. The patient's anonymity is maintained. For academic use of information, the data has been coded and no identifiable information of the participants is included in the manuscript.

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestNone declared.