Rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus are chronic autoimmune diseases affecting quality of life.

Patients and methodsTwo hundred patients diagnosed with RA and SLE were enrolled in this study. Four questionnaires (SF36, The Hamilton anxiety scale, The Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale, The Female Sexual Function Index) were administered.

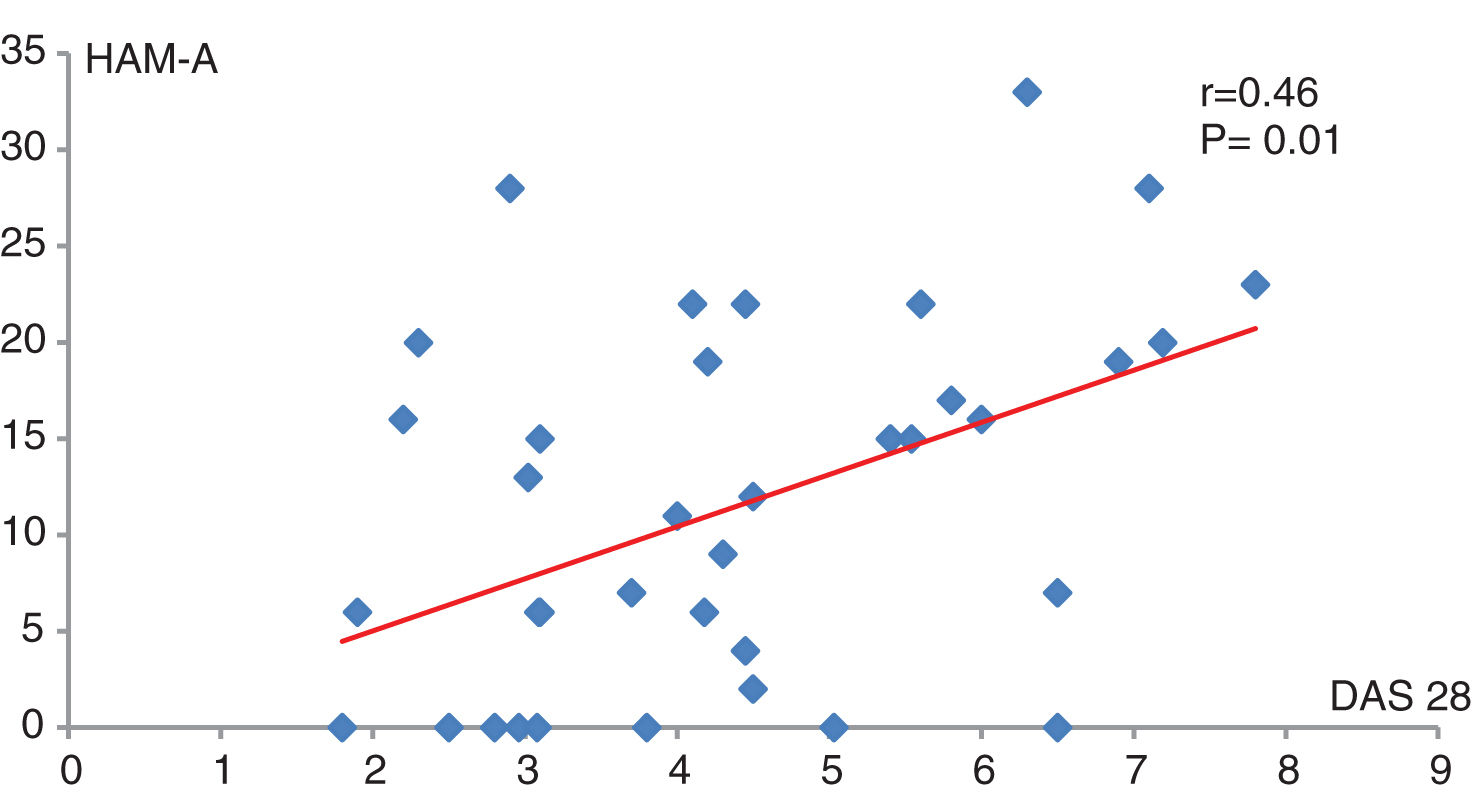

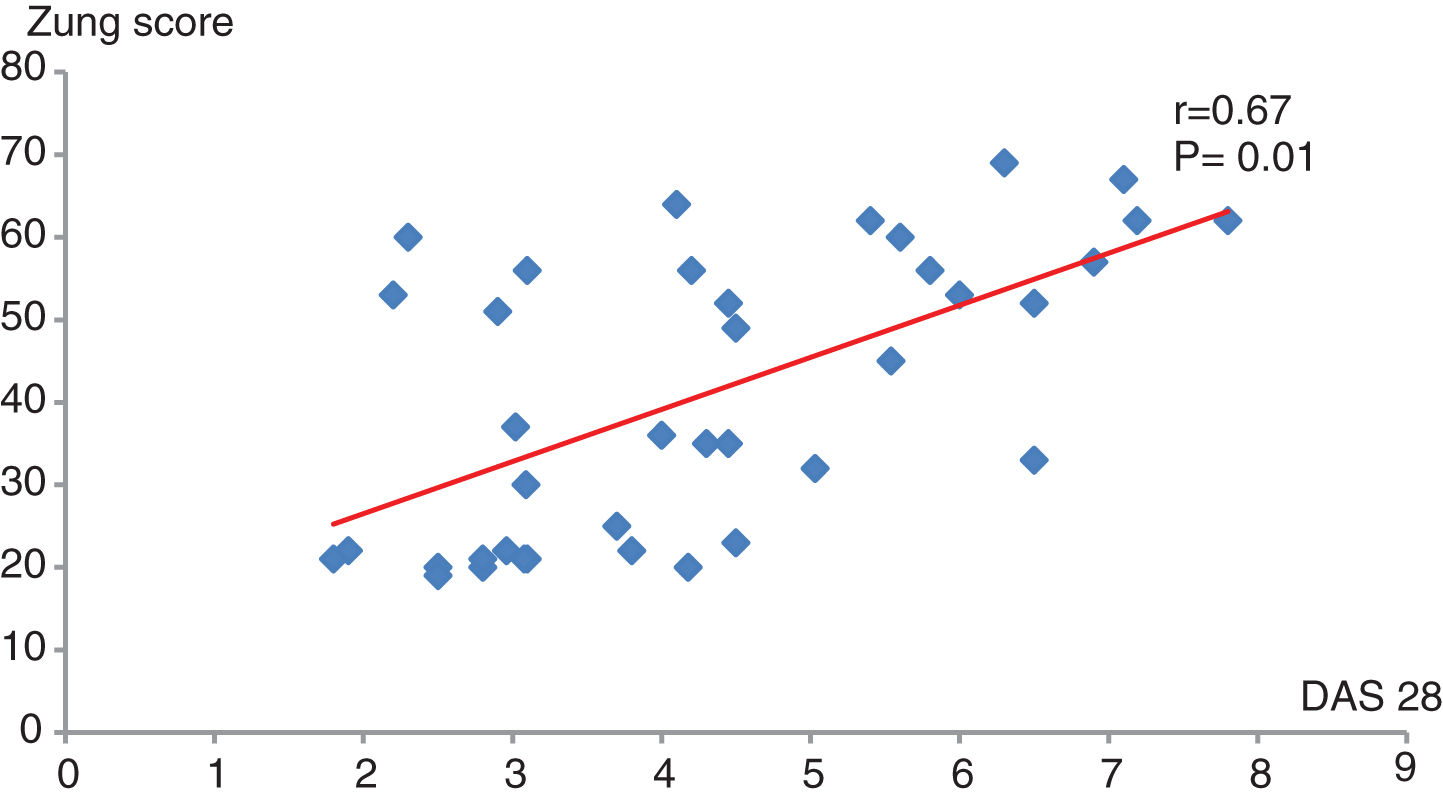

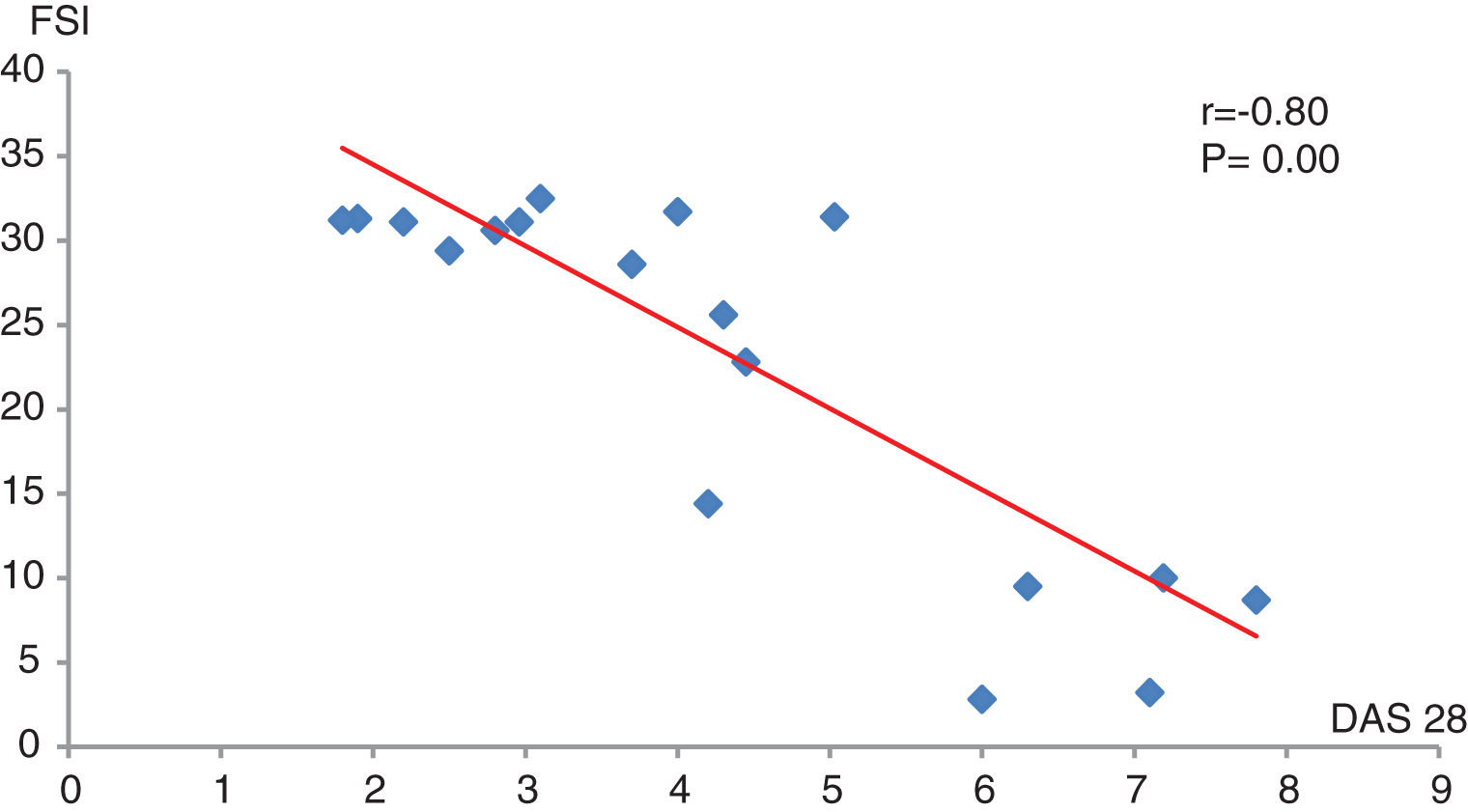

ResultsIn this cross-sectional study, all domains of SF36 had significant negative correlations with DAS 28. Patients with no flare and those with mild to moderate SLEDAI had significantly higher SF36 domains as compared to patients with severe SLEDAI (P<0.05). DAS 28 score had a positive moderate significant correlation with HAM-A (P=0.01, r=0.46). SLE patients with severe activity had higher HAM-A in contrast to other patients (17.75±7.65, P=0.02). DAS 28 score had positive significant correlation with Zung self-rating depression score (P=0.01, r=0.46). SLE patients with severe activity had significantly higher Zung depression score as compared to other patients (51.60±17.99, P=0.03). DAS 28 has significant strong negative correlation with female sexual index (r=−0.80, P=0.00). The female sexual index mean value was insignificantly lower in those with severe disease activity (14.60±9.50).

ConclusionThis study confirms that RA and SLE impair all aspects of quality of life. In RA patients disease activity negatively correlates with quality of life and sexual function, while there is a positive correlation with depression and anxiety. In SLE patients disease activity negatively correlates with quality of life and sexual dysfunction.

La artritis reumatoide (AR) y el lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) son enfermedades autoinmunes crónicas que afectan la calidad de vida.

Pacientes y métodosEn este estudio ingresaron 200 pacientes diagnosticados con AR y LES. Se administraron 4 cuestionarios, a saber: SF36, la escala de ansiedad de Hamilton, la escala de autoevaluación de depresión de Zung y el índice de función sexual femenina.

ResultadosEn el presente estudio transversal, todos los dominios de SF36 tuvieron correlaciones negativas significativas con la escala DAS28. Los pacientes sin exacerbaciones y los que presentaron un índice leve a moderado, tuvieron dominios SF36 significativamente más altos, en comparación con los pacientes con un índice SLEDAI severo (p<0,05). El DAS28 tuvo una correlación significativa moderada con la escala de Hamilton HAM-A (p=0,01; r=0,46). Los pacientes con LES con actividad severa presentaron un HAM-A más elevado, en comparación con otros pacientes (17,75±7,65; p=0,02). El DAS28 tuvo una correlación significativa positiva con el índice en la escala de depresión de Zung (p=0,01; r=0,46). Los pacientes con LES con actividad severa presentaron una calificación significativamente más alta en la escala de depresión de Zung, en comparación con otros pacientes (51,60±17,99; p=0,03). El DAS28 presenta una fuerte correlación significativa negativa con el índice de función sexual femenina (r=−0,80; p=0,00). El valor medio del índice de función sexual femenina fue significativamente menor en las pacientes con actividad severa de la enfermedad (14,60±9,50).

ConclusiónEste estudio confirma que la AR y el LES producen un deterioro en todos los aspectos de la calidad de vida. En el caso de los pacientes con AR, la actividad de la enfermedad se correlaciona negativamente con la calidad de vida y la función sexual, en tanto que existe una correlación positiva con la depresión y la ansiedad. En los pacientes con LES, la actividad de la enfermedad se correlaciona de manera negativa con la calidad de vida y la disfunción sexual.

Quality of life (QOL) is defined as the individuals’ perception of their position in life, in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. QOL is a major outcome predictor in patients with chronic conditions.1

It also represents the effects of an individual's personal social and economic capital, and how they communicate with their health status. QOL could thenbe defined as people's perception of life, values, goals, norms and interests.2

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a chronic auto-immune disease affecting about 1% of the general population.3 It is primarily a disease of the joints with episodes of inflammation, but may also affect other organs of the body. In severe cases RA usually leads to destruction of joints, disability, and life-threatening complications.4 It has significant diverse impact on patients’ QOL, affecting both physical and mental domains of well-being.5

QOL impairment has been reported in RA.6 The physical disability caused by RA is usually evident at the clinical level; however, the psychological and social morbidity can be easily missed by the clinician.7 In contrast to the healthy population, RA patient's QOL was reduced in several domains, such as physical health, level of independence, environment and personal beliefs.8

Systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease that can affect almost all organs of the body. The disease itself and disease-related effects and treatment side effects, all have a negative impact on the quality of life and life expectancy of SLE patients.9,10 Due to its systemic nature, SLE affects all aspects in the life of the patient: physical, psychological, and social wellbeing. The impact of changes caused by the disease process and treatment in the clinical course of the disease requires targeted actions for improving QOL as an essential factor to be considered by both patients and health care professionals.11 Patient QOL questionnaires are typically used to measure numerically the impact of disease morbidity on the daily life of the patient.12,13 Generic and disease-specific QOL instruments have been used for assessment in RA and SLE. The advantage of disease-specific measures is that they been specifically designed to measure health-related aspects particular to the disease. They are also more effective than generic instruments to assess treatment response.14 The aim of this study was to assess the impact of RA and SLE on patient's QOL, and its association to disease activity.

Patients and methods200 hundred patients were enrolled in this cross-sectional study, 100 patients diagnosed with RA according to the 2010 ACR – Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria15 and 100 patients diagnosed with SLE according to the 2015 ACR/SLICC revised criteria for the diagnosis of SLE.16

Patients less than 18 years, with co-morbidities such as malignancies or end stage organ failure, pregnant women, patients with other rheumatic diseases or bed ridden patients were excluded from the study.

A comprehensive medical history, including a thorough clinical assessment and evaluation, was completed in all patients. The disease activity score DAS 28 (ESR) was used to assess RA patients, and the SLEDAI score was used in SLE patients.17 A DAS28 score less than 2.6 was considered remission, less than 2.3 was considered low disease activity, and above 5.1 was indicative of high disease activity.18 Categories of disease activity were defined based on SLEDAI scores: no activity (SLEDAI=0), mild activity (SLEDAI 1–5), moderate activity (SLEDAI 6–10), high activity (SLEDAI 11–19), very high activity (SLEDAI≥20).19

All patients completed all the questionnaires. Using validated questionnaires in Arabic, the doctors then compiled the answers.

1-SF-36 is a multidimensional generic QOL questionnaire which comprises eight subscales including: physical functioning (PF), social functioning (SF), role limitations due to physical health problems (RP), role limitations attributable to emotional problems (RE), mental health (MH), vitality (VT), bodily pain (BP), and general health perceptions (GH). The higher the scores the better QOL. Finally, there are two main components: physical (PCS) and mental (MCS).20 The 1-SF-36 questionnaire scores based on recoding, summing and transforming dichotomous answers (yes or no), and ranking in a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 is the worst possible health state and 100 is the best possible health state.21

2 – The Hamilton anxiety scale (HAM-A) was one of the first questionnaires to measure anxiety symptoms and recurrence. It is widely used in both clinical evaluation and research. It consists of 14 items measuring both psychic anxiety (mental agitation and psychological distress) and somatic anxiety (physical complaints related to anxiety). The total score ranges from 0–56 (each item scores 0–4 where o=not present and 4 severe).

Mild anxiety (<17), mild to moderate (18–24) and moderate to severe (25–30).22

3 – The Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale is a simple questionnaire that can be self-administered and assesses the patient's depressed status. There are 20 items on the scale that measure depression-related affective, psychological and somatic symptoms. There are ten positively worded questions and ten negatively worded questions. Each question is scored on a scale of 1–4 (1 – “a little of the time”, 2 – “some of the time”, 3 – “good part of the time”, 4 – “most of the time”).

Scores range from 20–80. Most people with depression score between 50 and 69.23

4-The Female Sexual Function Index {FSFI}: A multidimensional self-reporting tool to assess female sexual function.24 It comprises six domains: desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain providing an overall score. Wiegel, Meston and Rosen did a psychometric evaluation of the questionnaire and developed a diagnostic cut-off point to identify women with and without sexual dysfunction. This optimal cut-off point was found to be a Total-FSFI score of 26.55. Low scores on FSFI indicate more problems with sexual functioning and high scores indicate fewer problems with sexual functioning.25

All patients were from the Physical Medicine, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Department and Outpatient Clinic, at Assiut University Hospitals, who visited the clinic from April 2019 to March 2020. The study was approved by the Ethical Medical Committee of Assiut University Hospitals, Assiut, Egypt, according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients submitted their written informed consent.

Statistical analysisThe Data were collected and analyzed using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS, version 20; IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Continuous data were expressed as mean±SD or median, whereas nominal data were expressed as frequency (percentage). The χ2-Test was used to compare the nominal data of different groups in the study, whereas the Student t-test was used to compare the means from two different groups, and analysis of variance test was for more than two groups. Pearson correlation was used to determine the correlation between DAS-28 and other continuous variables in the study. P value was significant if less than 0.05.

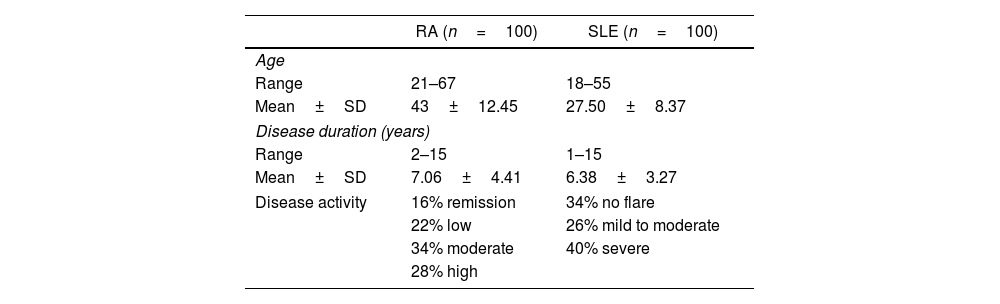

ResultsOne hundred female patients diagnosed with RA aged between 21 and 67 years with a mean±SD of 43±12.45 years. The disease duration ranged from 2–15 years with a mean±SD of 7.06±4.41years. Disease activity ranged from 1.80 to 7.80 with a mean±SD of 4.28±1.62. Based on DAS 28 (ESR), low, moderate and high activity were present in 22 (22%), 34 (34%), and 28 (28%) patients respectively, while 16 (16%) patients experienced remission.

The age range of the one hundred female patients diagnosed with SLE was between 18 and 55 years, with a mean±SD of 27.50±8.37 years. Disease duration ranged between 1 and 15 years, with a mean±SD of 6.38±3.27 years. Of the patients enrolled, 26 (26%) patients had mild to moderate activity based on SLEDAI, while 40 (40%) patients had severe activity and 34 (34%) patients had no flare (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of RA and SLE patients.

| RA (n=100) | SLE (n=100) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Range | 21–67 | 18–55 |

| Mean±SD | 43±12.45 | 27.50±8.37 |

| Disease duration (years) | ||

| Range | 2–15 | 1–15 |

| Mean±SD | 7.06±4.41 | 6.38±3.27 |

| Disease activity | 16% remission | 34% no flare |

| 22% low | 26% mild to moderate | |

| 34% moderate | 40% severe | |

| 28% high | ||

Data was expressed as range, mean±SD, and percentage.

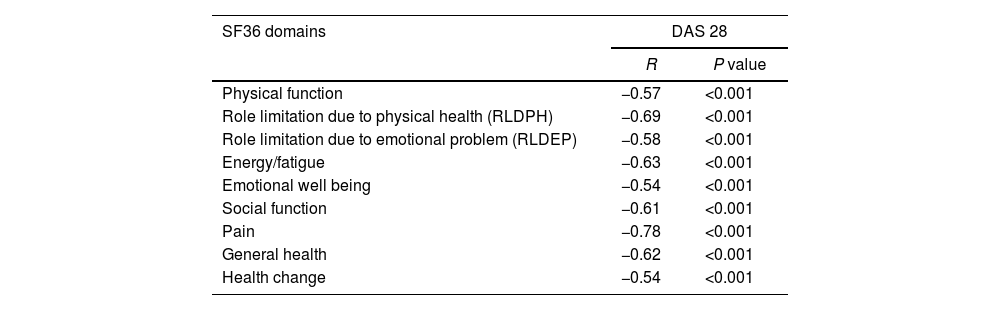

All domains of SF36 had significant negative correlations with DAS 28 in this study. The most affected domains were pain and role limitation due to physical health. Hence, this evidenced a major impact of RA affecting PCS rather than MCS (Table 2).

Relation between DAS 28 and domains of SF36 in RA patients.

| SF36 domains | DAS 28 | |

|---|---|---|

| R | P value | |

| Physical function | −0.57 | <0.001 |

| Role limitation due to physical health (RLDPH) | −0.69 | <0.001 |

| Role limitation due to emotional problem (RLDEP) | −0.58 | <0.001 |

| Energy/fatigue | −0.63 | <0.001 |

| Emotional well being | −0.54 | <0.001 |

| Social function | −0.61 | <0.001 |

| Pain | −0.78 | <0.001 |

| General health | −0.62 | <0.001 |

| Health change | −0.54 | <0.001 |

Data was expressed as r, indicating strength of correlation while P value expressed significance of correlation.

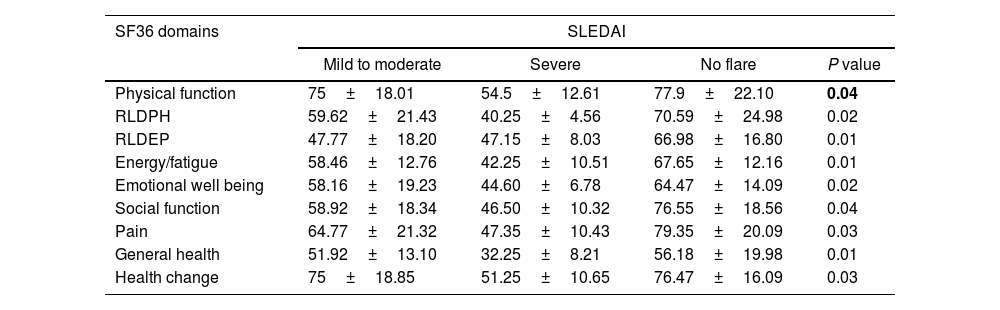

Patients with no flare, as well as those with mild to moderate SLEDAI had significantly higher SF36 domains in comparison to patients with severe SLEDAI (P<0.05), as shown in Table 3.

Relation between SLEDAI and domains of SF36 in SLE patients.

| SF36 domains | SLEDAI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild to moderate | Severe | No flare | P value | |

| Physical function | 75±18.01 | 54.5±12.61 | 77.9±22.10 | 0.04 |

| RLDPH | 59.62±21.43 | 40.25±4.56 | 70.59±24.98 | 0.02 |

| RLDEP | 47.77±18.20 | 47.15±8.03 | 66.98±16.80 | 0.01 |

| Energy/fatigue | 58.46±12.76 | 42.25±10.51 | 67.65±12.16 | 0.01 |

| Emotional well being | 58.16±19.23 | 44.60±6.78 | 64.47±14.09 | 0.02 |

| Social function | 58.92±18.34 | 46.50±10.32 | 76.55±18.56 | 0.04 |

| Pain | 64.77±21.32 | 47.35±10.43 | 79.35±20.09 | 0.03 |

| General health | 51.92±13.10 | 32.25±8.21 | 56.18±19.98 | 0.01 |

| Health change | 75±18.85 | 51.25±10.65 | 76.47±16.09 | 0.03 |

Data was expressed in as mean±SD. P value was significant if < 0.05. RLDPH, Role limitation due to physical health, RLDEP, Role limitation due to emotional problem; SLEDAI, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index

No significant differences were found between RA and SLE patients in terms of the SF36 domains (P>0.05).

Relation between DAS28 and Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A) in RA patientsThere were 83.3% of patients in remission, 89% patients with low disease activity and 75% of patients with moderate disease activity who exhibited mild anxiety based on Hamilton Anxiety scale.

DAS 28 score had positive moderate significant correlation with HAM-A (P=0.01, r=0.46) (Fig. 1).

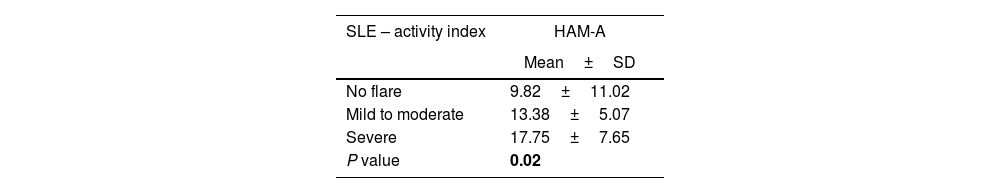

Relation between SLEDAI and Hamilton Anxiety Scale in SLE patientsMost of the patients with no flare, and the majority of those with mild to moderate disease activity, experienced mild anxiety based on HAM scale, while 35% of patients with severe SLE activity index, experienced moderate to severe anxiety based on HAM scale.

Moreover, patients with severe activity had higher HAM-A, in contrast to other patients (17.75±7.65, P=0.02), as shown in Table 4.

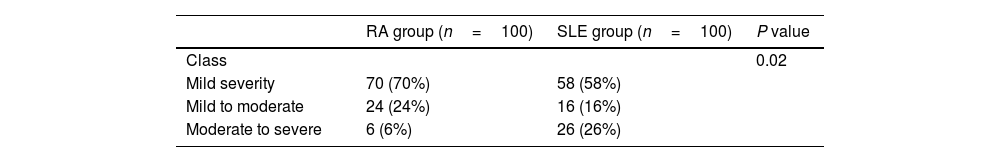

Hamilton anxiety scale (HAM-A) in RA and SLE patientsThe disease severity based on HAM-A was mild, mild to moderate and moderate to severe in 70 (70%), 24 (24%), and 6 (6%) patients with RA and 58 (58%), 16 (16%), 26 (26%) patients with SLE, respectively, with significant differences between both groups (P=0.02), as shown in Table 5.

Hamilton activity scale (HAM-A) in RA and SLE patients.

| RA group (n=100) | SLE group (n=100) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class | 0.02 | ||

| Mild severity | 70 (70%) | 58 (58%) | |

| Mild to moderate | 24 (24%) | 16 (16%) | |

| Moderate to severe | 6 (6%) | 26 (26%) |

Data expressed as frequency (percentage). P value was significant if <0.05. SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; RA: rheumatoid arthritis.

The majority of patients with low disease activity (82%) and those with moderate disease activity (71%) were not depressed, while most of the patients (85.7%) with high disease activity were depressed, based on Zung self-rating depression score. DAS 28 score had positive significant correlation with Zung score (P=0.01, r=0.46) (Fig. 2).

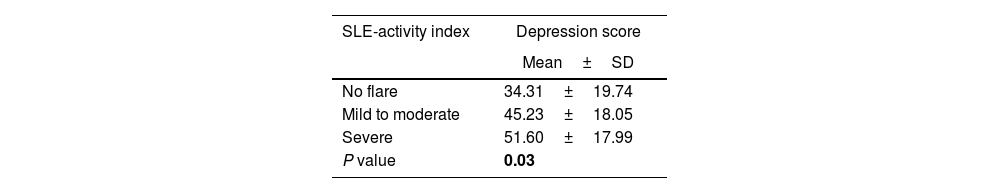

Relation between SLEDAI and Zung self-rating depression scoreThere were 40 depressed and 60 non-depressed SLE patients. Most of the patients with no flare (76.5%) and those with mild to moderate disease activity (61.5%), were not depressed while the majority (55%) of patients with a severe disease activity were depressed, based on Zung self-rating depression score (Table 6). Likewise, patients with severe activity had significantly higher Zung self-rating depression scores in comparison to other patients (51.60±17.99, P=0.03).

Zung self-rating depression score in RA and SLE patientsBased on Zung self-rating depression score, 58 (58%) patients with RA, and 60 (60%) patients with SLE were not depressed, while 42 (42%) patients with RA and 40 (40%) patients with SLE were depressed, with no significant difference between the two groups.

Relation between DAS28 and female sexual function index in RA patientsAs observed, DAS 28 has a significant strong negative correlation with female sexual index (r=−0.80, P=0.00). Of one hundred female RA patients, 20 of them (20%) had sexual dysfunction according to FSFI (Fig. 3).

Relation between SLEDAI and female sexual function index in SLE patientsOf the 100 female patients with SLE, 30 (30%) had sexual dysfunction based on FSFI.

According to our findings, the mean female sexual index in patients with a severe disease activity (14.60±9.50), and in those with mild to moderate disease activity (11.76±8.06) was lower, as compared to those with no flare (19.03±10.76), but the difference was not statistically significant.

Female sexual index in RA and SLE patientsThe female sexual index was significantly higher in patients with RA versus SLE patients (23.53±10.60 vs. 15.34±8.77; P=0.01).

DiscussionThis study focused on QOL in RA patients using the SF36 questionnaire, which is the most widely used generic measure of health status; our results indicate that patients with high disease activity have a poor quality of life, while patients with low disease activity and on remission, show better quality of life. The results also show a significant negative correlation between disease activity and both mental and physical domains of the SF-36, with impairment of all SF-36 domains. However, the most affected domains are pain and role limitation due to impaired physical health; hence, PCS is more affected than MCS.

According to the study, disease activity significantly correlated with both components of SF 36. A significantly high PCS score was found among RA patients with low DAS28 and those on remission, as compared to those with moderate and high DAS28 (P<0.001); this is consistent with a study which found impairment in all of the 8 SF36 domains in RA patients, where the score of each domain was less than 50% of its maximum score. These results are also consistent with a study conducted on 26 Egyptian patients with early RA, showing impaired QOL using the SF-36 tool.26

Birrell et al. studied 86 RA patients and found that there was moderate to marked impact on the health status based on SF-36, with significant differences between the normal population and the chronic disease states such as low back pain. The conclusion was that SF-36 is a practical tool for RA patients.27

This study showed a reduction in most of the QOL outcomes in patients with active SLE, when assessed with SF-36; it highlighted that patients with no flare and those with mild to moderate SLEDAI, had significantly higher SF36 domains in comparison to those patients with severe SLEDAI (P<0.05). All domains of SF36 had significant negative correlations with SLEDAI, and this is consistent with Stoll et al. who using the SF-36 reported a significant association between disease activity assessed by the British Isles Lupus Activity Group System (BILAG) and QOL.28

Moreover, our study is consistent with previous studies showing that the SLEDAI score with a 4-week window, negatively affect every domain in SF-36, with the exception of the perceived general health.29 These progressive changes in QOL could be due to a number of factors, such as SLE progression over time, constant coping with a chronic disease, and various management strategies required (frequent medical visits, laboratory examinations, etc.). One additional consideration is that most SLE patients are young adult females, at an age in which their physical, psychological and social stability is not yet fully established. The disease usually started at a critical time in their lives, when they are trying to establish relationships, start a family and pursue a career. Consequently, these patients experienced a wide range of physical, psychological and social problems. Abu-Shakra M et al. found that SF-36 scores were correlated with BILAG and SLEDAI scores, suggesting SF-36's divergent construct validity; this means, the tool provides for an independent assessment of the impact of SLE.30 Similarly, Thumboo et al. reported that improvements in SF-36 scores correlate with decreases in disease activity and damage, which is consistent with this study.31

This study found that the majority of RA patients with low disease activity had mild to moderate anxiety based on Hamilton Anxiety scale; furthermore, 75% of the patients with moderate disease activity, and 83.3% of the patients on remission, exhibited mild anxiety based on HAM-A scale. DAS 28 score had positive significant correlation with HAM-A (P=0.01, r=0.46).

This is consistent with a study by Scott et al., who found that many patients with RA experienced anxiety, evidencing a strong correlation between anxiety and disease activity (DAS28).32

Another study reported that the prevalence of anxiety in RA cases was higher than that in the normal population, and also noticed that patients with early RA patients also experience anxiety.33

A study by Clarke et al. reported that anxiety results in a significant rate of comorbidity34; yet another study, reported that anxiety is common in RA cases, and the level of anxiety in RA is similar to that experienced by patients with non-inflammatory rheumatological diseases such as osteoarthritis, mechanical lumbar pain, and fibromyalgia.35

Some authors found in their studies that the treatment of accompanying psychiatric disorders reduces the activity of the disease, in other words, that anxiety has a significant positive correlation with disease activity which is consistent with our study.36

This study also measured anxiety of SLE patients through HAM-A and found that the majority of patients with no flare (76.5%), and those with mild to moderate disease activity (69.2%), had mild anxiety based on HAM-A scale, while 35% of those with severe activity experienced moderate to severe anxiety. Furthermore, patients with severe activity had significantly higher HAM-A scores in comparison to other patients (P value=0.02).

This study was consistent with a previous study which reported that the anxiety disorders were twice as prevalent among SLE patients as compared to controls.37

In this study, the majority of RA patients with low disease activity (82%) as well as those with moderate disease activity (71%) were not depressed, while the majority (85.7%) of patients with high disease activity were depressed, based on Zung self-rating depression score. DAS 28 exhibited a positive strong significant correlation with Zung score (P=0.01, r=0.46). This is consistent with a study by Smedstad et al., who reported a highly significant increase in depression in rheumatoid patients, as compared to the control population.38 The results in this study are also consistent with another study which found a strong correlation between depression and disease activity (DAS28).39 A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that depression was more frequent in individuals with RA than in healthy individuals.40

In 2013, another meta-analysis of 72 studies that included 13,189 RA patients found that the prevalence of major depression was 16.8%.41

This study found that 40% of SLE patients were depressed. The majority of patients with no flare (76.5%) and those with mild to moderate disease activity (61.5%) were not depressed, while the majority (55%) of those with severe disease activity were depressed, based on Zung self-rating depression score. Moreover, patients with severe activity had significantly higher Zung scores in comparison to other patients (P value=0.03); this in contrary to a study by Kheirandish M et al., which reported that no relation was found between disease activity and depression.42

Neuropsychiatric (NP) disorders were present in about 70% of the patients diagnosed with SLE.43 A previous study found that severe activity of the disease was significantly associated with an increased prevalence of depression among SLE patients, which is consistent with our results.44

RA-associated sexual problems could be related to physical and psychological causes including, sexual disfunction, depression, altered body image, and difficulty in taking certain positions when the hips or the knees are severely affected, vaginal dryness causing dyspareunia, and fatigue and joint pain during intercourse, are the key manifestations of sexual disability; the latter is experienced by 50–61% of RA patients.45

This study found that 10 out of 46 (21.7%) female patients with rheumatoid arthritis suffer from sexual dysfunction, especially those with functional disability and high disease activity. DAS 28 has a significant strong negative correlation with the female sexual functioning index (r=−0.80, P=0.00). Abdel-Nasser et al., examined 52 RA patients and reported that sexual dysfunction was present in 60% of the cases.46

The prevalence of FSD in RA patients in a study by EL Miedany et al., ranged from 45% to 62%.47 A study by Khnaba et al., in 2016 assessed sexual function in women with RA using the FSFI score, and they reported a lower prevalence of FSD (29.4%).48 Coskun et al., in 2014 reported that 68.75% of Turkish women with RA had sexual dysfunction according to the FSFI score, versus 15% of healthy controls.49

A study by Frikha et al., reported that 7 out of 10 women with RA experienced sexual dysfunction assessed by FSFI score and that all of the FSFI subscales were affected.50 Another Turkish study reported in RA patients a mean FSFI total score of (22.6±9.0), significantly lower than the controls (34.6±8.3).51

This study reported that there is no significant correlation between FSFI and SLEDAI (P value 0.55), and also that 30% of females with SLE had sexual dysfunction. The mean female sexual function index was insignificantly lower in patients with severe and with mild to moderate disease activity, as compared to those with no flare (P value 0.55). This contrasts with a previous study showing that disease activity was significantly correlated with impaired sexual function.52

A study by Daleboudt et al., reported that SLE patients have lower sexual function than patients with others chronic diseases.53 Impaired partner relationships were usually caused by marital status, age, disturbed body image and depression, whereas impaired sexual function were caused by body image, emotional distress, employment, disease activity, and depression.52

High disease activity is usually associated with a poor quality of life in patients with RA and SLE; our recommendation is that QOL should be apart of the routine assessment for patients with high disease activity.

ConclusionThis study confirms that RA and SLE impairs of all aspects of quality of life. In RA patients disease activity negatively correlates with quality of life, sexual function, and positively correlates with depression and anxiety. In SLE patients disease activity negatively correlates with quality of life and sexual dysfunction.

Ethical approvalAll co-authors agreed to this submission, and they have obtained the required ethical approvals. They have also given the necessary attention to ensure the integrity of the work.

FundingNo funding was received to prepare this paper.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.