Depressive episodes are frequent in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. These episodes are related to a vast number of clinical and psychosocial variables. Nevertheless, the relationship between the number of COPD exacerbations and depression has not been extensively studied in the Colombian Caribbean. The objective was to determine the relationship between COPD exacerbations and depression in a sample of outpatients in Santa Marta, Colombia.

MethodsA cross-sectional analytical study was designed in which COPD adult patients participated. The number of COPD exacerbations (none versus one or more) and the risk of depression were documented. The crude and adjusted association was established by calculating the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI).

ResultsThe study included 408 patients aged between 40 and 102 years (mean 72.9±10.2), and 58.8% were male. 105 patients (25.9%) reported one or more exacerbations in COPD, and 114 patients (27.9%) were at risk for depression. The crude relationship between exacerbations and depression was statistically significant (OR=1.80; 95%CI, 1.12-2.89) and after adjusting for sex (OR=1.99; 95%CI, 1.23-3.23).

ConclusionsThe number of COPD exacerbations among outpatients in Santa Marta, Colombia is related to depression. Longitudinal studies are needed in Colombia.

Los episodios depresivos son frecuentes en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC). Estos episodios están relacionados con un gran número de variables clínicas y psicosociales. Sin embargo, la relación del número de exacerbaciones de la EPOC con la depresión ha sido poco estudiada en el Caribe colombiano. El objetivo es determinar la relación entre las exacerbaciones de la EPOC y depresión en una muestra de pacientes ambulatorios de Santa Marta, Colombia.

MétodosSe diseñó un estudio transversal analítico en el que participaron pacientes adultos con EPOC. Se documentó el número de exacerbaciones de la EPOC (ninguna frente a una o más) y el riesgo de depresión. La asociación bruta y ajustada se estableció mediante el cálculo de las razones de oportunidad (OR) y el intervalo de confianza del 95% (IC95%).

ResultadosSe incluyó a 408 pacientes con edades entre 40 y 102 años (media, 72,9±10,2), y el 58,8% eran varones. Informaron una o más exacerbaciones en la EPOC 105 pacientes (25,9%), y 114 (27,9%) estaban en riesgo de depresión. La relación bruta entre exacerbaciones y depresión fue estadísticamente significativa (OR=1,80; IC95%, 1,12-2,89) y después ajustar por sexo (OR=1,99; IC95%, 1,23-3,23).

ConclusionesEl número de exacerbaciones está relacionado con depresión en pacientes que viven con EPOC en Santa Marta, Colombia. Se necesitan estudios longitudinales en Colombia.

In the global context, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has had a more significant impact last years, and since 2012 it has been the fourth cause of mortality of adult patients. Therefore, it is a medical condition of high importance in public health.1 In Colombia, the epidemiological transition to chronic non-communicable diseases places chronic diseases of the lower respiratory tract are the third cause of mortality and its prevalence of 6%.2

In Latin America, the PLATINO study (Latin American Research Project on Lung Obstruction) reported that COPD prevalence was 19.7% in Montevideo, 16.9% in Santiago, 15.8% in San Pablo, 12.1% in Caracas, and 7.8% in Mexico City.3 In Colombia, the PREPOCOL study reported that COPD prevalence was 8.9% in the general population of five large cities.4

Comorbidity with depressive disorders is frequent in COPD patients; prevalence rates are between 15 and 40% in clinical samples.5 This prevalence of depression is higher than other chronic illnesses, such as diabetes and heart disease.6,7 In COPD patients, depression is associated with decreased therapeutic adherence, poor quality of life, and lower smoking cessation.8

COPD comorbidity and depression can act synergistically and increase annual exacerbations of COPD. Exacerbations require hospital admission; further, it deteriorates patients’ quality of life.9 The frequency of presentation of exacerbations is a significant predictor of the progression of COPD,10 and deterioration of lung functionality, and nutritional status, with an increase in mortality.11

The relationship between COPD and depressive disorder can be bidirectional. The major depressive disorder may increase the risk of COPD since it is frequently associated with cigarette and other substance consumption,12,13 and persisting cigarette use.14 Consequently, depression increases the risk of COPD exacerbations.15 Likewise, exacerbations may increase the risk of meeting the criteria for depression.16,17 Exacerbations predict repeated hospitalizations because they represent a stressor that increases the vulnerability to present depression.18

General and specialist liaison psychiatrists should be aware that many people with long-term physical health conditions, such as COPD often meet the criteria for a mental disorder and make a careful assessment and assist treating physicians in effectively managing mental comorbidity.19

The objective of the present study was to determine the relationship between exacerbations and depression in COPD patients from Santa Marta, Colombia.

MethodsDesign and ethical issuesA cross-sectional study was designed. The authors considered the ethical aspects of research involving humans from Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Colombian Ministry of Health. The project had the endorsement of a Research Ethics Committee. All participants signed informed consent, as stipulated by the Helsinki Declaration.20

ParticipantsA non-probability sample of consecutive patients diagnosed with COPD was taken from three Santa Marta, Colombia, institutions between August and December 2019. A sample of no less than 267 people was estimated for an expected prevalence of 25% of depression (margin error of 5 and a confidence level of 95%).21 This sample size would also make it possible to estimate the leading association and adjust with up to five variables in a block, which is, 67 cases of depression were expected. This number of cases makes it possible to adjust for five variables at a rate of 10 cases for each variable.22 The researchers included 18-year-old patients and excluded pregnant women and people with cognitive impairment, limiting the Brief Zung Self-rating Depression Scale response.

MeasurementsIt was recorded sociodemographic data (age, sex, marital status, socioeconomic status), clinical findings such as the combined evaluation and GOLD classification, and responses on Brief Zung Self-rating Depression Scale (BZSDS).

GOLD classificationThe GOLD classification for COPD is based on the degree of airflow limitation measured with forced expiratory flow per minute (FEV1). According to the degree of restriction, patients are classified into 1, 2, 3, and 4, from least to most considerable limitation.1

Combined evaluationThe combined evaluation of COPD patients includes symptoms, number of exacerbations, the severity of symptoms, and quality of life measured with CAT (COPD Assessment Test).23 Patients are classified into four stages, A, B, C, and D, from most minor to most severe.1

Depression riskDepression risk was quantified with BZSDS. The tool comprises 10 items that quantify symptoms during the last 2 weeks. Each item presents 4 options from never to always, rated from 1 to 4; therefore, the total possible scores are between 10 and 40. Scores>20 were categorized as depression risk. In Colombia, previously, BZSDS has shown high internal consistency.24 This scale is a Spanish version of the English original of 20 items Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale.25 In the present study, the BZSDS presented Cronbach's alpha of .78.

COPD exacerbationsEpisodes of accentuation of symptoms that required in-hospital management with the administration of antibiotic therapy were considered exacerbations.1,26

ProcedurePatients were invited to participate in the consultation waiting room, where the objectives for signing the informed consent were explained. Then, they completed BZSDS, which is not part of the usual care protocol in the outpatient consultation of patients with COPD in Colombia.

Statistical analysisThe main variables, frequencies, and percentages were described for categorical variables and central tendency and dispersion measures for quantitative variables. Subsequently, the association between exacerbations as independent variables and depression as dependent variables was established. Demographic variables, GOLD stage, and combined evaluation were taken as confounding variables; they were dichotomized for this process. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). The variable adjusting was followed using Greenland's recommendations, considering the variables that showed p values of less than 20% and induced a change of more than 10% in the OR value of the association between exacerbations and depression.27 The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to assess the goodness of fit.28 An OR value with a lower 95%CI limit>1.0 was considered a significant association. The analysis was performed with the IBM-SPSS program, version 23.0.29

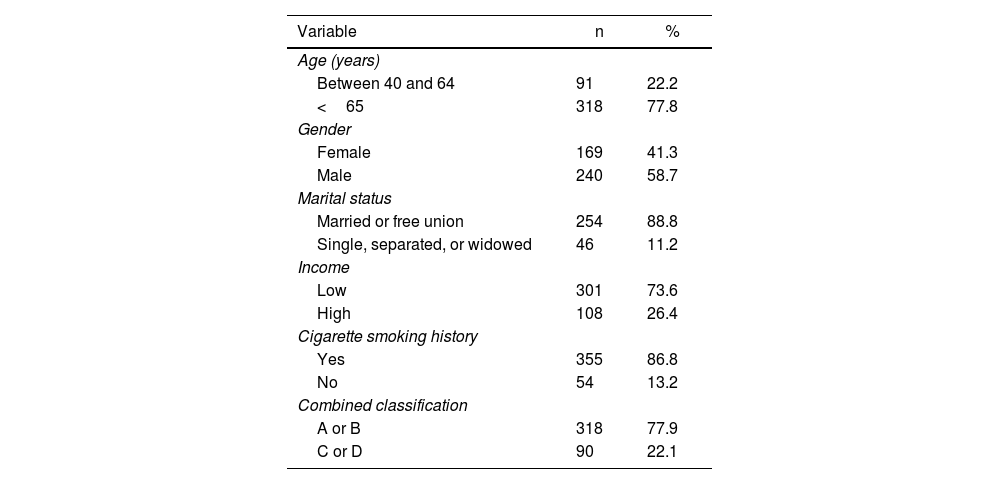

ResultsA sample of 408 patients participated in the study. The participants’ ages were observed to be between 40 and 102 years (mean, 72.9±10.2), 317 (77.7%) of them were 65 or older, and 91 were between 40 and 64 years (22.3%). More demographic and clinical information is presented in table 1.

Demographical and clinical description of participants.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Between 40 and 64 | 91 | 22.2 |

| <65 | 318 | 77.8 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 169 | 41.3 |

| Male | 240 | 58.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or free union | 254 | 88.8 |

| Single, separated, or widowed | 46 | 11.2 |

| Income | ||

| Low | 301 | 73.6 |

| High | 108 | 26.4 |

| Cigarette smoking history | ||

| Yes | 355 | 86.8 |

| No | 54 | 13.2 |

| Combined classification | ||

| A or B | 318 | 77.9 |

| C or D | 90 | 22.1 |

A total of 105 patients (25.7%) reported one or more exacerbations of COPD. Furthermore, BZSDS scores were observed between 10 and 32 (mean, 17.0±5.3), and 114 patients (27.9%) scored for depression risk.

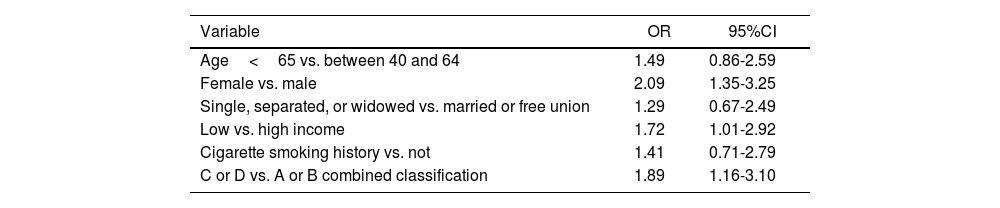

One or more exacerbations were statistically associated with depression risk (OR=1.80; 95%CI, 1.12-2.89), even after adjusting for gender (OR=1.99; 95%CI, 1.23-3.23). It was not adjusted for the combined evaluation since it includes the number of exacerbations, and there was evident collinearity. Other variables were not shown as confounding. All crude associations for depression are presented in table 2.

Crude associations for depression.

| Variable | OR | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age<65 vs. between 40 and 64 | 1.49 | 0.86-2.59 |

| Female vs. male | 2.09 | 1.35-3.25 |

| Single, separated, or widowed vs. married or free union | 1.29 | 0.67-2.49 |

| Low vs. high income | 1.72 | 1.01-2.92 |

| Cigarette smoking history vs. not | 1.41 | 0.71-2.79 |

| C or D vs. A or B combined classification | 1.89 | 1.16-3.10 |

The present study observed that the number of exacerbations is significantly associated with depression risk among COPD outpatients in Santa Marta, Colombia. This finding is consistent with previous research; for example, Miravitlles et al.13 found a statistically significant correlation between the number of exacerbations and scores on the Beck Inventory for Depression (r=.21 and r=.23, respectively). Likewise, they documented that the number of exacerbations in the last year was related to depression (OR=4.82; 95%CI, 3.24-7.17). Tse et al.14 found an association between COPD exacerbations in the latter and moderate depression (OR=1.46; 95%CI, 1.02-2.11).

Depression is a clinical disorder related to constitutional and environmental factors.30 Psychosocial stressors increase the risk of depression in particularly susceptible people.12 Chronic diseases that cause significant limitations in daily life are configured as long-term stressors in the life of patients.15 The care of people living with COPD can be improved by better integrating the support of human talent specialized in mental health in primary care, chronic disease management programs, and during hospital stays.19 Educational and psychological measures aimed at improving understanding of the disease, motivating patients to adhere more effectively to treatments, and providing coping strategies can help reduce the risk of exacerbations and depression in people with COPD.19,31 Screening for depression in COPD patients can be performed by trained nursing staff.32 However, the participation of general or liaison psychiatrists is necessary for the accuracy of diagnosis and the most appropriate treatment.32,33 Proper management of COPD reduces the risk of depression in vulnerable people and improves the quality of life.6–11,19

This study shows the cross-sectional association between exacerbations and depression in patients from the Colombian Caribbean. In the same way, it took as a dependent variable the presence of depression; a more significant number of studies have been handled as an independent variable.10,17 However, the analysis does not allow clarity on the direction of causality. It should be borne in mind that the available evidence shows a bidirectional path between exacerbations and depression; when it is more significant, the number of exacerbations is greater, the probability of depression.34 At the same time, with more depression, is a greater possibility of COPD exacerbation.35 Readers should consider possible patient selection bias because this was not a random sample and many COPD patients with barriers to health care access rarely participate in clinical research.21 Moreover, future studies should investigate manifestations of demoralization because the BZSDS cannot measure demoralization. Demoralization is widespread in people living with long-term disabling illnesses.36 Depression and demoralization share symptoms,37 and differentiation is a clinical challenge.38

It is concluded that the number of exacerbations seems to increase depression risk among COPD outpatients from clinical institutions in Santa Marta, Colombia. Longitudinal studies are needed with a more significant number of participants.

FundingThe Research Vice-rectory of the University of Magdalena financed the entire project through Resolution 0516 of August 9th, 2019.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests related to this research.