To investigate the prevalence of physicians and nurses involved in an adverse event within mental health.

Materials and methodsA quantitative, cross-sectional study was performed. Six Flemish psychiatric hospitals (Belgium) participated in this exploratory cross-sectional study. All psychiatrists and nurses working in these hospitals were invited to complete an online questionnaire in March 2013.

Results28 psychiatrists and 252 nurses completed the survey. 205 (73%) of the 280 respondents were personally involved at least once in an adverse event within their entire career. Respondents reported that the adverse event with the greatest impact was related to suicide in almost 64% of the cases. About one in eight respondents considered quitting their job because of it. Almost 18% declared that due to the impact of the event, they believed that the quality of the administered care was affected for longer than one month. Respondents stated that they received much support of colleagues (95%), the chief nurse (86%) and the partner (71%). Colleagues seemed to be most supportive in the recovery process.

ConclusionsPhysicians and nurses working in inpatient mental health care may be at high risk to being confronted with an adverse event at some point in their career. The influence on health professionals involved in an adverse event on their work is particularly important in the first 4–24h. Professionals at those moments had higher likelihood to be involved in another adverse event. Institutions should seriously consider giving support almost at that time.

Investigar la prevalencia de médicos y enfermeras implicados en un episodio adverso en salud mental.

Materiales y métodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio cuantitativo y transversal. Seis hospitales psiquiátricos de Flandes (Bélgica) participaron en este estudio transversal de exploración. Se solicitó a todos los psiquiatras y enfermeras que trabajan en estos hospitales que completaran un cuestionario en línea en marzo de 2013.

ResultadosVeintiocho psiquiatras y 252 enfermeras respondieron la encuesta. Doscientos cinco (73%) de los 280 encuestados participaron personalmente, al menos una vez, en un episodio adverso en toda su carrera. Los encuestados informaron de que el episodio adverso con mayores repercusiones estuvo relacionado con el suicidio en casi el 64% de los casos. Aproximadamente, uno de cada 8 encuestados consideró dejar el trabajo a causa de ello. Casi el 18% declaró que, debido a las repercusiones del episodio, creían que la calidad de la atención administrada se vio afectada durante más de un mes. Los encuestados declararon que recibieron mucho apoyo por parte de sus colegas (95%), la enfermera jefe (86%) y la pareja (71%). Al parecer, los compañeros fueron los más comprensivos en el proceso de recuperación.

ConclusionesLos médicos y enfermeras que trabajan en atención hospitalaria de salud mental pueden correr un gran riesgo de enfrentarse a un episodio adverso en algún momento de su carrera. La influencia de los profesionales sanitarios implicados en un episodio adverso en su trabajo es especialmente importante en las primeras 4-24h. Los profesionales en esos momentos tenían mayor probabilidad de verse implicados en otro episodio adverso. Las instituciones deberían considerar seriamente el hecho de prestar apoyo casi en el mismo momento.

The focus on errors began with the Institute of Medicine report “To err is human: building a safer health system”, published in 1999.1 In 2002, a Patient Safety Committee was formed as part of the Council on Quality Care. This was a component of the American Psychiatric Association. Despite more than a decade of focus on improving patient safety, recent studies found that the current state of serious adverse events is still high.2 Although making errors is human, it must be avoided as much as possible.1 Therefore, one of the major focuses of the health care organizations for the past years was the prevention of medical mistakes. An important goal of quality improvement measures should be to institute a reduction of ‘adverse events’ to zero.

Recent studies estimate that approximately 10% of hospital admissions are associated with an adverse event.3 An adverse event is defined as an undesirable, although not necessarily unexpected, outcome resulting in prolonged hospitalization, disability or death, caused by healthcare management.1 Adverse events have a significant impact on patient morbidity and mortality. They also result in increased healthcare costs due to longer hospital stays. A substantial proportion of adverse events are preventable.2,4,5 Adverse events occur within a complex socio-technical system in healthcare, it is not necessarily the result of one person making a mistake at the frontline of healthcare. Conditions in the system often enable the adverse event to occur.1,3 A systems approach assumes healthcare workers are fallible and errors are inevitable.3

In 2002, the National Quality Forum (United States of America) published a first report, which defined 28 so-called “serious reportable events” in healthcare. This report encompasses serious adverse events occurring in hospitals that are largely preventable and of concern to both the public and to healthcare workers. Some of these incidents, such as patient suicide, attempted suicide, or self-harm resulting in serious disability, while being cared for in a health care facility, occur in inpatient mental health care.

When an adverse event occurs, there can be more than one victim.6 Dr. Albert Wu stated that patients are the first and most important victims of adverse events. However, health care providers can also be traumatized by these events, they are second victims of adverse events.7 A second victim is defined as: “A health care provider involved in an unanticipated adverse patient event, medical error, and/or a patient related injury who becomes victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event. Frequently second victims feel personally responsible for the unexpected outcomes and feel as though they have failed their patient, second guessing their clinical skills and knowledge base”.8 A review of Seys et al. reported that the second victim phenomenon will often lead to an emotional, professional and personal impact on the caregiver.8 Feelings often become worse over time and the emotional trauma can be long-lasting.8,9 When second victims use coping strategies that may be harmful in the long or short term, they are at risk of burnout, depression and posttraumatic disorder.8 Coming to terms with an adverse event can be extremely distressing for front-line professionals. Research suggests that exposure to adverse events can undermine professionals’ functioning and evoke feelings of incompetence, cause them to question their professional career and ultimately contribute to burnout.10 In mental health care, psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses are at risk of becoming a second victim.11

To date, there is limited evidence on the prevalence and impact of adverse events on mental health workers. Cullen et al. reported that four overarching categories of errors in general medical settings also occurred in inpatient psychiatry.12 Only a few studies on adverse events such as medication errors and suicide exist.11–16 Cottney et al. reviewed the literature on medication errors within mental health care and reported an error occurrence rate of 3.3% per medication round. 11% of the errors were of serious clinical severity.14 Soerensen et al. reported 17% errors of which 8% were assessed as potentially harmful.5 Haw et al. detected 25.9% medication administration errors.15 According to Nath and Marcus, of the nearly 30.000 suicides each year, 5–6% occur in inpatient psychiatric settings.16

Gaffney et al. studied the impact of a patient's suicide on front-line staff in Ireland. Concerns for the bereaved family, feelings of responsibility for the death and having a close therapeutic relationship with the patient are key factors. The factors influence the adjustment and coping of a professional in the aftermath of a patient's suicide.10 Takahashi et al. studied the impact of inpatient suicide on psychiatric nurses and their subsequent need for support. The results indicated that nurses exposed to inpatient suicide suffer significant mental distress. However, the low availability of systematic post-suicide mental health care programs and the lack of suicide-related education initiatives and mental health care for nurses are problematic. There are no formal systems for identifying and evaluating the psychological effects of patient's suicide on nurses.13

In this study, the objective was to investigate the prevalence of physicians and nurses involved in an adverse event within mental health, the impact of the adverse event on the professional career and the support received. The following research questions were posed:

- 1.

What is the prevalence of mental health workers involved in an adverse event?

- 2.

Which adverse events have the biggest impact?

- 3.

What is the impact of the adverse event on the professional career of the mental health worker and on the quality of care?

- 4.

Which support was received after the adverse event?

A quantitative, cross-sectional study was performed. Data were collected in March 2013, using an online questionnaire. The online questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first asked about demographic and job-related information and the second asked the number of adverse events in which the respondents were involved. Three levels of involvement were provided as options for response: personally involved during their entire career, personally involved during the last 6 months and having witnessed an adverse event on the ward during the last six months. Only participants, who were personally involved in adverse events during their entire career or in the past six months, were asked to fill in the third part, which explored the impact of the incident on the participant. They were asked to elaborate on the incident with the biggest impact in which they were personally involved, indicating what kind of support they received, and the impact the event had on their professional career and their perceptions of the quality of care they were able to give to patients subsequently.

The online questionnaire was composed by researchers at KU Leuven, University of Leuven. The type of questions were a combination of open questions (e.g. “How often did you get personally involved in the following adverse events: suicide on the ward, attempted suicide on the ward, self harm on the ward, etc.?”, “Could you describe the incident with the biggest impact?”), closed questions (e.g. “Have you ever been personally involved in an adverse event during your entire career?”, “Have you witnessed an adverse event during the last 6 months?”) and there were questions with multiple choice answers (e.g. “Did you got the opportunity to recover in the aftermath of the incident?” Possible answers were: yes and it was desirable, yes but it wasn’t desirable, no but it was desirable, no and it wasn’t desirable).

The hyperlink of this web survey was distributed by the participating hospitals to their physicians and nurses. To increase the response rate, two reminders were sent (after two and after six weeks). Informed consent from the respondents was obtained by filling in the questionnaire.

Sampling descriptionSix Flemish psychiatric hospitals were invited to participate, based on their long lasting collaboration with the University of Leuven and their experience with event reporting. The included hospitals serve 8.8% of the total psychiatric hospital beds in Flanders, Belgium.

Target population and settingAll psychiatrists and nurses working in the selected Flemish hospitals (N=1150) were invited to participate. All other health care workers were excluded from the study.

InterventionsThe study was explorative without any intervention.

Statistical analysisData were entered into and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Version 18.0). The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics only.

Ethical approvalEthical approval was granted by the ethics committee of the University of Leuven.

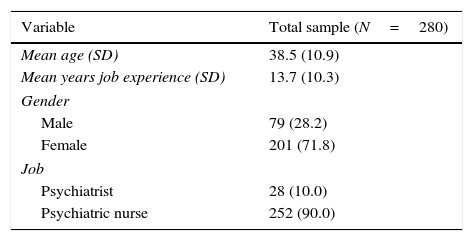

ResultsResponse rateTwenty-eight psychiatrists and 252 nurses filled in the online questionnaire. A response rate of 19.9% was reached. The demographic characteristics are listed in Table 1.

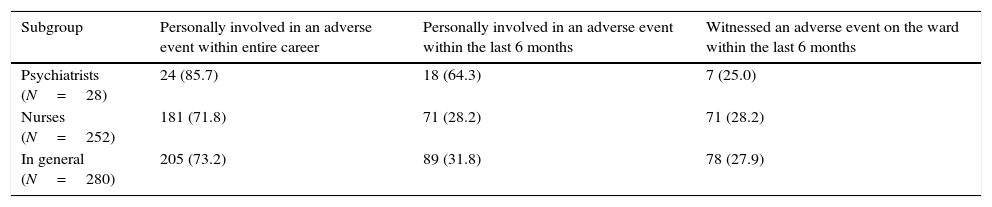

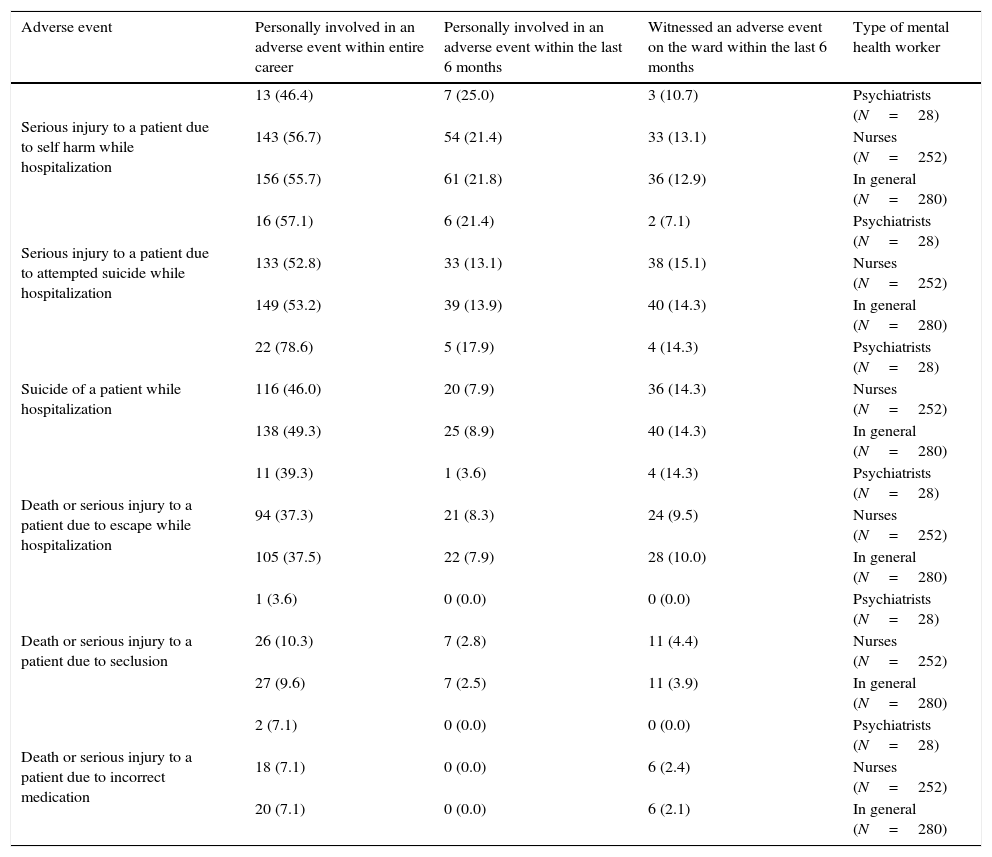

Research question 1: what is the prevalence of mental health workers involved in an adverse event?In general, 205 out of the 280 respondents (73.2%) had already been personally involved in an adverse event during their entire career, of which 89 (31.8%) during the last 6 months. Adverse events such as self-harm (55.7%), attempted suicide (53.2%) and suicide (49.3%) appeared to be the most frequent. Furthermore, there were also participants who had already been personally involved more than three times in self-harm (25.7%), attempted suicide (17.1%) and suicide (8.2%). 46.0% of the psychiatric nurses and 78.6% of the psychiatrists had been personally involved in a patients suicide. 78 out of the 280 respondents (27.9%) witnessed an adverse event on the ward within the last six months. The prevalence of adverse events – by type of mental health worker is shown in Table 2. The involvement of psychiatrists and nurses in adverse events – by type of adverse event is shown in Table 3.

Prevalence of adverse events – by type of mental health worker.

| Subgroup | Personally involved in an adverse event within entire career | Personally involved in an adverse event within the last 6 months | Witnessed an adverse event on the ward within the last 6 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatrists (N=28) | 24 (85.7) | 18 (64.3) | 7 (25.0) |

| Nurses (N=252) | 181 (71.8) | 71 (28.2) | 71 (28.2) |

| In general (N=280) | 205 (73.2) | 89 (31.8) | 78 (27.9) |

Values are given as N (%).

Involvement of psychiatrists and nurses in adverse events – by type of adverse event.

| Adverse event | Personally involved in an adverse event within entire career | Personally involved in an adverse event within the last 6 months | Witnessed an adverse event on the ward within the last 6 months | Type of mental health worker |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious injury to a patient due to self harm while hospitalization | 13 (46.4) | 7 (25.0) | 3 (10.7) | Psychiatrists (N=28) |

| 143 (56.7) | 54 (21.4) | 33 (13.1) | Nurses (N=252) | |

| 156 (55.7) | 61 (21.8) | 36 (12.9) | In general (N=280) | |

| Serious injury to a patient due to attempted suicide while hospitalization | 16 (57.1) | 6 (21.4) | 2 (7.1) | Psychiatrists (N=28) |

| 133 (52.8) | 33 (13.1) | 38 (15.1) | Nurses (N=252) | |

| 149 (53.2) | 39 (13.9) | 40 (14.3) | In general (N=280) | |

| Suicide of a patient while hospitalization | 22 (78.6) | 5 (17.9) | 4 (14.3) | Psychiatrists (N=28) |

| 116 (46.0) | 20 (7.9) | 36 (14.3) | Nurses (N=252) | |

| 138 (49.3) | 25 (8.9) | 40 (14.3) | In general (N=280) | |

| Death or serious injury to a patient due to escape while hospitalization | 11 (39.3) | 1 (3.6) | 4 (14.3) | Psychiatrists (N=28) |

| 94 (37.3) | 21 (8.3) | 24 (9.5) | Nurses (N=252) | |

| 105 (37.5) | 22 (7.9) | 28 (10.0) | In general (N=280) | |

| Death or serious injury to a patient due to seclusion | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | Psychiatrists (N=28) |

| 26 (10.3) | 7 (2.8) | 11 (4.4) | Nurses (N=252) | |

| 27 (9.6) | 7 (2.5) | 11 (3.9) | In general (N=280) | |

| Death or serious injury to a patient due to incorrect medication | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | Psychiatrists (N=28) |

| 18 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (2.4) | Nurses (N=252) | |

| 20 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (2.1) | In general (N=280) |

Values are given as N (%).

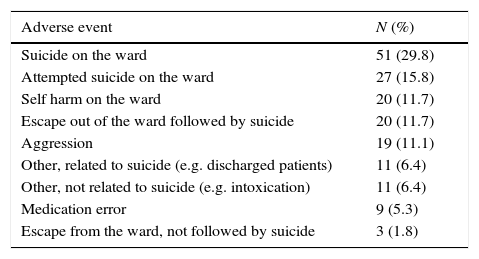

When asked which adverse event had the biggest impact, 63.7% (N=171) reported an incident related to suicide. This number is rising up to 70.2% in psychiatrists and nurses with more than 22 years of job experience in mental health care. Suicide related incidents lead to the patient's death in 50.9% of the cases. See Table 4 for more details about the adverse events with the biggest impact.

Classification of adverse events with the biggest impact (N=171).

| Adverse event | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Suicide on the ward | 51 (29.8) |

| Attempted suicide on the ward | 27 (15.8) |

| Self harm on the ward | 20 (11.7) |

| Escape out of the ward followed by suicide | 20 (11.7) |

| Aggression | 19 (11.1) |

| Other, related to suicide (e.g. discharged patients) | 11 (6.4) |

| Other, not related to suicide (e.g. intoxication) | 11 (6.4) |

| Medication error | 9 (5.3) |

| Escape from the ward, not followed by suicide | 3 (1.8) |

Values are given as N (%).

In the aftermath of a serious adverse event, 42.4% of the mental health workers gave more attention to details and 19.2% of them even changed their work attitude to anticipate on future incidents. More than 1 out of the 5 respondents asked for more advice from colleagues, while 17.5% claimed to be affected by the adverse event. 21 mental health workers (12.3%) left their job after an adverse event. Four of them are still considering it.

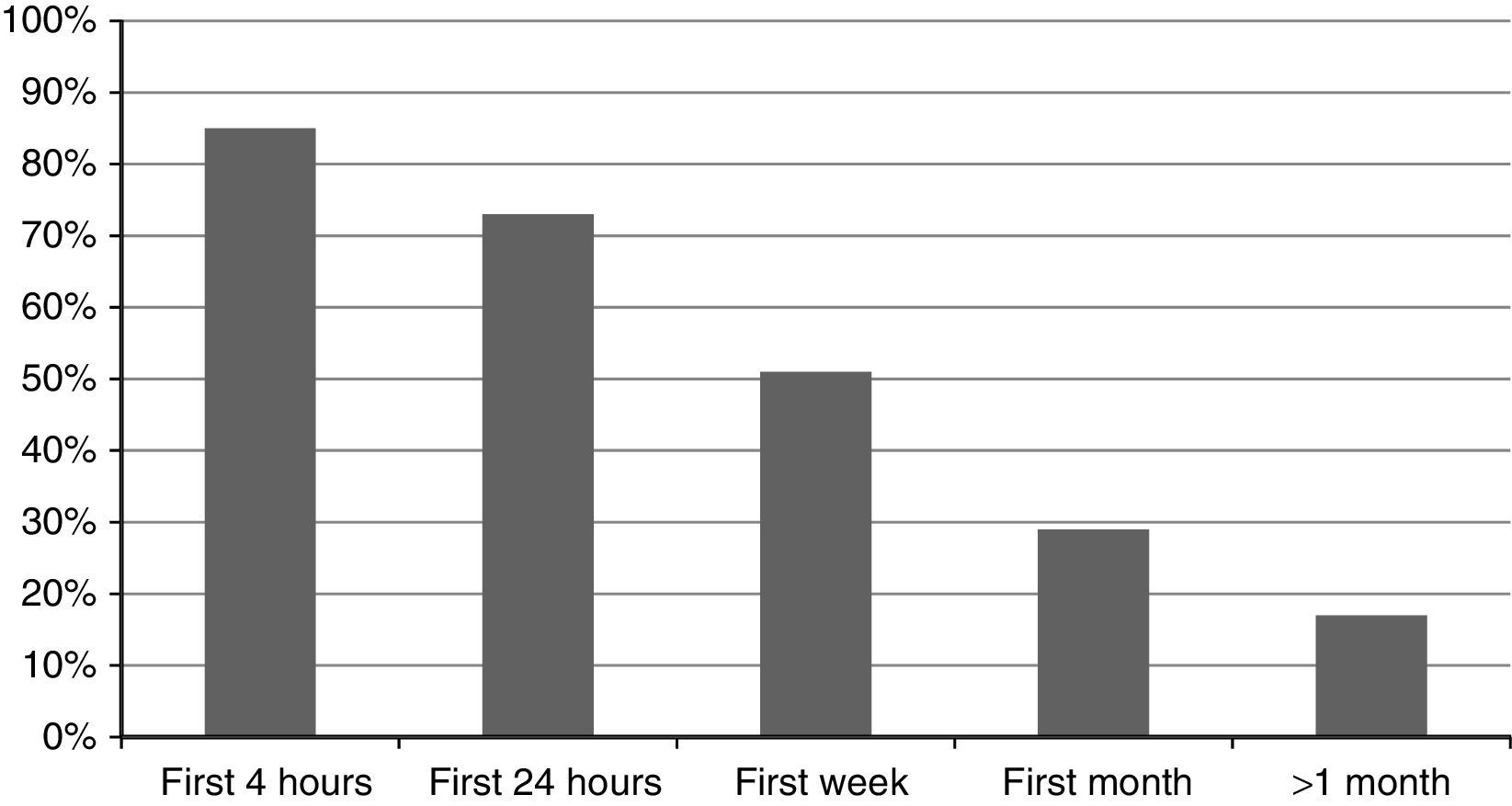

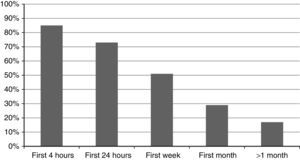

Nearly 85.0% of the mental health workers stated that in the first 4h after the adverse event, they were not able to provide the same quality of care as before the adverse event. Almost 18.0% of the respondents declared that the quality of care administered was still seriously affected longer than one month after the incident. The impact on the professional career is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Negative impact incident on quality of care. In Fig. 1 is given: the percentages of respondents who believed the quality of care was affected a bit or a lot.

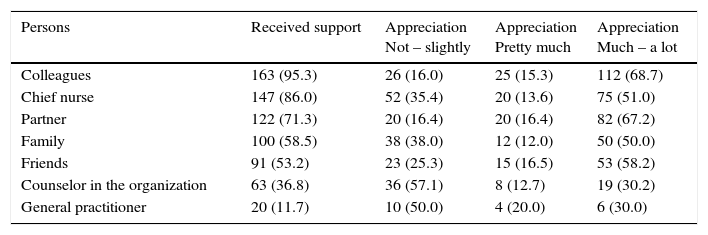

Respondents stated that they received much support of colleagues (95.3%), the chief nurse (86.0%) and their husband, wife or partner (71.3%). Colleagues seemed to be most supportive in the recovery process of a mental health worker involved in an adverse event. Support of colleagues was highly appreciated (by at least 67.0%). Support of the chief nurse, family and friends was appreciated by half of the mental health workers. Support of a counselor or a general practitioner was less appreciated (30%). While almost 74.9% considered support after being involved in an adverse event as necessary, 84 mental health workers (49.1%) did not get the opportunity to recover from the adverse event. The time to recover varied from a couple of minutes to some weeks. See the results of the received support and appreciation in Table 5.

Received support and appreciation.

| Persons | Received support | Appreciation Not – slightly | Appreciation Pretty much | Appreciation Much – a lot |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colleagues | 163 (95.3) | 26 (16.0) | 25 (15.3) | 112 (68.7) |

| Chief nurse | 147 (86.0) | 52 (35.4) | 20 (13.6) | 75 (51.0) |

| Partner | 122 (71.3) | 20 (16.4) | 20 (16.4) | 82 (67.2) |

| Family | 100 (58.5) | 38 (38.0) | 12 (12.0) | 50 (50.0) |

| Friends | 91 (53.2) | 23 (25.3) | 15 (16.5) | 53 (58.2) |

| Counselor in the organization | 63 (36.8) | 36 (57.1) | 8 (12.7) | 19 (30.2) |

| General practitioner | 20 (11.7) | 10 (50.0) | 4 (20.0) | 6 (30.0) |

Values are given as N (%).

In this study, we reported a high prevalence of adverse events. 73.2% of the respondents had already been personally involved at least once in an adverse event during their entire career, of which 31.8% during the last 6 months. Self-harm, attempted suicide and suicide appeared to be the most frequently occurring. It is not clear whether these results correspond with the literature, as there is limited evidence on the prevalence of adverse events in mental health care. Cullen et al. reported errors in four overarching categories: treatment errors (33.9%), diagnostic errors (8.9%), preventive errors such as patient falls, suicide and violence were the most commonly mentioned (38.4%), the other mentioned errors (18.8%) fell into categories often related to transfers and discharges.12 According to this study, mental health workers are at high risk for getting involved in an adverse event. Bates acknowledges that psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses are at substantial risk for getting involved in an adverse event.4 However, it is not clear whether these individuals really are second victims. There is an important difference between an adverse event (such as a needlestick injury) and being traumatized by a drastic event such as seeing a serious car accident, or the death of a colleague. Not everyone who gets personally involved in an adverse event, becomes automatically a second victim. Seys et al. reported that the prevalence of second victims in health care varies from 10.4% over approximately 30–43.3%.8

In this study, suicide of a patient seemed to be the adverse event with the biggest impact. Our study confirms that mental health workers are at high risk for getting personally involved in a patient's suicide.11 The impact of patient's suicide on mental health workers is already well described,13,17 its called “the trauma” for the mental health worker. Probably the fact that this adverse event results very often in a patient's death, plays an important role. Also the fact that a suicide can be unexpected, constitutes to the experience of trauma. The perception of avoidable adverse events seemed to be strongly related to the type of incident. Suicide is often unpredictable.18 Despite the efforts of family, friends, other social agencies and mental health staff, tragically, some people will commit suicide. In some cases, these people are very unwell and end up acting in ways that result in harm or death. It is not always possible to prevent that happening. However, health professionals have a duty to do everything in their power to keep patients safe while they are receiving treatment. Therefore, it is important to consider suicide as an adverse event that should not occur on a ward. The heart of the matter in the inpatient mental health care is to create a safe environment for patients at risk for suicide.19 Therefore, monitoring suicidal ideation and behavior is an important element in the prevention of suicides in mental healthcare. The use of the European Psychiatric Association Guidance on suicide treatment and prevention is warranted to assure the quality of the monitoring.20

In our study, almost 18% of the mental health workers believed the quality of care they delivered was affected in a negative way after experiencing an adverse event. According to Blacklock, the accumulation of stress has an impact on the individual's ability to perform within the organization and on work-relationships.21 Additional stress, caused by an adverse event, could result in improved or reduced achievements.22,23 Courtenay and Stephens reported that physicians witnessing a suicide, often resulted in improvement of the quality of care.24 Bowers et al. reported that adverse events had a continuing influence up to ten years after they had occurred. Heightened alertness, attentiveness to risk assessment, more rigorously pursued policies, greater use of containment methods like special observations and higher environmental security may or may not be good.19

A small part considered leaving the job in the aftermath of an adverse event. Dropping out, surviving and thriving have been identified by Alexander et al. and Scott et al. as possible strategies in coping with an adverse event.25,26 The observation that respondents gather more advice from colleagues was confirmed by many studies.17,21 Van Dusseldorp et al. reported that the emotional intelligence of psychiatric nurses seemed significantly bigger than the normal population implying that it means they could cope with emotional intense situations in a more adequate way.27

According to 75% of the respondents, it is important to receive support in the aftermath of an adverse event. In this study, respondents felt that support from colleagues was the most valuable, an observation that was confirmed by many studies.11 Experiencing prolonged stress at work requires emotional support from colleagues.21 Bowers et al. reported that support was appreciated by staff who were emotionally traumatized by some adverse events.19 Mental health workers are in a difficult situation; they have to take care for other patients, they could also be affected by the incident and they have to deal with their own emotions and feelings. Noteworthy, almost the half of the respondents did not receive support. A study of Van Gerven et al. revealed that only 50.8% of the participating hospitals in Belgium had a protocol for second victim support.28 Subjective stress seemed significantly related to the possibility to recover from the incident, which was confirmed by Campbell and Fahy in the case of suicide.29 Bates et al. stated that we need to promote a non-punitive workplace culture that encourages organizational learning.4 Seys et al. reported that to improve the quality of care and to sustain a culture of patient safety, there is a need to support health workers who are suffering as second victims.8

Methodological limitationsSome important methodological limitations need to be taken into account when interpreting the results. Among these is the low response rate. The low response rate can be due to the relatively short time to complete the questionnaire (7 weeks), the way the professionals were invited to take part (online questionnaire), weariness of survey completion due to participating in many surveys and a blame culture in reporting errors. To enhance the response, respondents could also be offered the choice of completing a questionnaire in written form. Another important limitation of this study is sampling bias due to a non-random sample of the psychiatric hospitals. A relatively small number of hospitals covering limited number of beds took part in this study, which affects the external validity of the results. Selection bias could be expected. Being involved in an adverse event is a motive or a threshold to fill in the questionnaire. Also self-reported questionnaires can be helpful to learn about how people think, feel and behave.

The focus was on the adverse event, which had the biggest impact. Because of this, we could not explore the consequences of adverse events with lower impact. Future research on adverse events could focus more on the impact of violence and aggression against mental health workers.

The setting is another important limitation, the study was conducted solely in hospital settings. Up to 90% of mental health care in some countries is delivered in the community including treatment for mental health crises. The inpatient workforce is in Belgium of high importance, this may differ to other countries. The home treatment system for mental health crises in Belgium is in full development.

In Belgium, there is no specific law to promote open disclosure among mental health workers and there is no national anonymous incident reporting system, these are local. The lack of a protection law might be a limitation to notify among psychiatrists. Although the number is growing, the lack of anonymous incident reporting systems might be a limitation because it could be used as a learning tool in healthcare institutions.

A final important limitation is retrospective and prospective impact bias. Impact bias is defined as the tendency to overestimate the length or the intensity of future feelings in reaction to either good or bad occurrences.

Implications for practiceGiven the widespread frequency of adverse events and the second victim response, health care facilities should anticipate that health workers within their systems will experience such events, and they should be prepared to offer assistance as needed. Guidelines could be useful in quality assurance in mental health care. Comprehensive guidelines should not only cover psycho-pharmacotherapy, but also the “talking” aspects of psychosocial interventions.20

Adverse events in inpatient mental health care demands more care in the aftermath. The therapeutic relationship between patients and mental health workers is stronger than in somatic hospitals, which makes additional support necessary.30 Health professionals who are second victims of adverse events must be supported. Support for health workers after an adverse event is of great importance, it has also an impact on patient safety and the organization itself.28

Larger studies are needed to investigate the prevalence and impact of adverse events in mental health care.

Future research should investigate whether these findings remain consistent in studies with a higher response rate, across other health care workers and settings such as community mental health services. Exploring the present and ideal support for mental health workers who were personally involved in adverse events is also necessary. Another important issue is how mental health workers could be prepared for involvement in adverse events.

To conclude, the findings of our study provide important insight in the experience of the respondents about the high prevalence of adverse events in inpatient mental health care. The impact on the professional career of the mental health worker should not be underestimated. The impact of the adverse events has been quantified in intensity and it lasts till at least one month after the incident. Recommendation on intensive support to these second victims should take these data in to account. In conclusion, second victims in mental health care should be taken into consideration and become a priority of mental health organizations.

FundingThe author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We hereby thank all involved hospitals and clinicians for participating to this study.