To conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis that compares two prophylactic protocols for treating post-surgical infections in cardiac surgery.

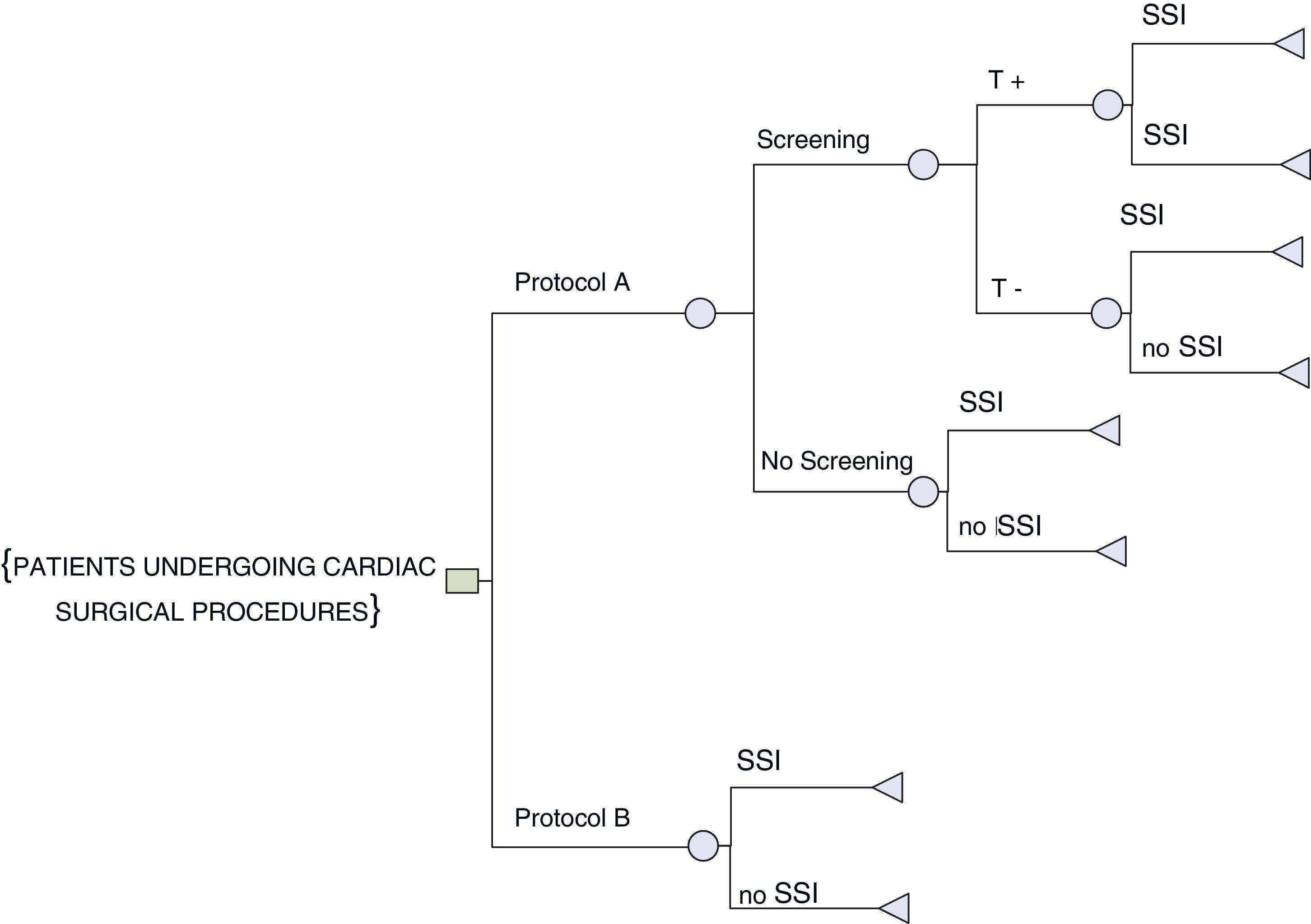

MethodsA cost effectiveness analysis was done by using a decision tree to compare two protocols for prophylaxis of post-surgical infections (Protocol A: Those patient with positive test to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonization received muripocin (twice a day during a two-week period), with no follow-up verification. Those who tested negative did not receive the prophylaxis treatment; Protocol B: all patients received the mupirocin treatment). The number of post-surgical infections averted was the measure of effectiveness from the health system's perspective, 30 days following the surgery. The incidence of infections and complications was obtained from two cohorts of patients who underwent cardiac surgery Hospital. The times for applying the two protocols were validated by experts. They cost were calculated from the hospital's analytical accounting management system and Pharmaceutical Service. Only direct costs were taken into account, no discount rates were applied. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated. A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was performed.

ResultsA total of 1118 patients were included (721 in Protocol A and 397 in Protocol B). No statistically significant differences were found in age, sex, diabetes, exitus or length of hospital stay between the two protocols. In the control group the rate of infection was 15.3%, compared with 11.3% in the intervention group. Protocol B proves to be more effective and at a lower cost, yielding an ICER of €32,506.

ConclusionUniversal mupirocin prophylaxis against surgical site infections (SSI) in cardiac surgery as a dominant strategy, because it shows a lower incidence of infections and cost savings, versus the strategy to treat selectively patients according to their test results prior screening.

Realizar un análisis de coste-efectividad que compare dos protocolos profilácticos para el tratamiento de infecciones posquirúrgicas en cirugía cardíaca.

MétodosEl análisis de coste-efectividad se llevó a cabo mediante un árbol de decisiones para comparar dos protocolos sobre profilaxis de infecciones posquirúrgicas (en el protocolo A, los pacientes con resultado positivo por colonización de Staphylococcus aureus resistente a la meticilina (SARM) recibieron mupirocina (dos veces al día durante 2 semanas) sin verificación de seguimiento. Aquéllos con resultado negativo no recibieron profilaxis. En el protocolo B, todos los pacientes recibieron el tratamiento con mupirocina). La medida de la efectividad fue el número de infecciones posquirúrgicas que se habían evitado a los 30 días desde la perspectiva del sistema de salud. La incidencia de infecciones y complicaciones se obtuvo a partir de dos cohortes de pacientes a quienes se practicó cirugía cardíaca. Algunos expertos validaron los tiempos de aplicación de los dos protocolos. Los costes se calcularon a partir del sistema de contabilidad analítica del hospital y el Servicio de Farmacia. Sólo se tuvieron en cuenta los costes directos y no se aplicaron tasas de descuento. Se calculó la relación de coste-efectividad incremental (ICER) y se realizó un análisis de sensibilidad probabilístico.

Resultadosse incluyó a 1.118 pacientes (721 en el protocolo A y 397 en el protocolo B). No hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas en cuanto a edad, sexo, diabetes, muerte o duración de la estancia hospitalaria entre los dos protocolos. En el grupo control, la tasa de infección alcanzó el 15,3% y el 11,3% en el grupo de intervención. El protocolo B ha demostrado ser más eficaz y con menor coste, pues se ha obtenido un ICER de 32.506€.

Conclusiónla profilaxis universal con mupirocina frente a infecciones en el sitio quirúrgico (SSI) en cirugía cardíaca se muestra como una estrategia dominante ya que muestra menor incidencia de infecciones y un ahorro de costes que la estrategia para tratar selectivamente a los pacientes de acuerdo con los resultados obtenidos en la prueba de cribado previa.

Post-surgical infections or surgical site infections (SSI) constitute an important public health problem because they are associated with higher morbimortality rates and increased health expenditures for longer hospital stays and surgical procedures. Although strategies aimed at combating this problem, high infection rates are still being registered, with rates of 10% being observed in developed countries.1,2 Among the most significant are infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), the causal agent of >25% of nosocomial infections,3 although this rate is declining.

The literature shows that MRSA carriers are between two and nine times more likely to develop an infection after an invasive or surgical procedure, and 10 times more likely to be at risk for mortality due to a post-surgical infection.2,4

The prevalence of MRSA varies from country to country and in Spain it stands at about 30–38%.5–7 However, in hospital settings its prevalence can be as high as 90% in intensive care units (ICU) and 55–83.3% in surgical services.2,7 Moreover, a distinction can be made between the hospital-acquired MRSA population and the community-acquired MRSA population: 31% and 14%, respectively.8

A number of studies have demonstrated that antibiotic prophylaxis is effective in preventing SSI9,10 and the most frequently used is nasal mupirocin ointment, accompanied by body washing or oral rinsing with chlorhexidine. Two Cochrane reviews evaluated both prophylactic techniques. The first review found that a mupirocin-based prophylaxis was associated with a significant decrease in the rates of hospital-acquired MRSA.7,10 In contrast, the second review showed that preoperative washing of the skin surface with antiseptics was not associated with any statistically significant reduction in infections at the surgical site, when compared with the placebo.11

In 2013 of a systematic review was published, about the Nasal decolonization, which have included 17 studies that assessed nasal decolonization. The meta-analysis shows that nasal decolonization was associated with a decreased rate of Gram positive surgical site infections. More specifically, nasal decolonization was significantly protective against S aureus surgical site infections among patients who underwent orthopedic or cardiac surgical procedures.12

In the Spanish health context, a systematic review estimates that 31.7% of the problems related to surgical procedures are avoidable, which could thus represent a savings of about 192,000,000€ annually.13 Economical evaluation studies that refer to the prevention of SSI by MRSA are still scarce, with Vanderbergh and Davey being pioneers.14,15 Following a review of the literature we can confirm that all the evaluations conducted were analyses on cost-effectiveness and can be divided into two main groups: the pertinence of pre-surgical screenings16–18 and the effectiveness of treatment.14,19

This study has been conceived against the backdrop of improving the effectiveness of health care, increasing patient safety, and improving patient care.20

The aim of this study was to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis that compares two prophylactic protocols for preventing post-surgical infections in cardiac surgery in Malaga's Virgen de la Victoria Hospital (Spain).

MethodologyA cost effectiveness analysis was done by using a decision tree to compare two protocols for prophylaxis of post-surgical infections. The number of post-surgical infections averted (considering as the differences in the cumulative incidence of infections between both protocols) was the measure of effectiveness, under the assumption that the absence of an infection was attributable to the intervention (protocol B).16,21 The analyses were conducted from the health system's perspective, 30 days following the surgery (in accordance with the definition for SSI).

The incidence of infections (with 95% confidence intervals) and complications was obtained from two cohorts of patients who underwent cardiac surgery in the Virgen de la Victoria University Hospital, Malaga (HUVV) from the beginning of January 2006 until the end of June 2009.

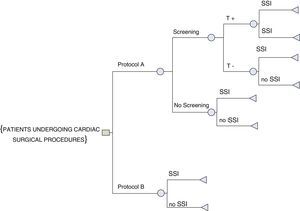

Comparison strategiesThe surgical service introduced two different protocols in two separate periods for the prophylaxis of post-surgical infections due to MRSA (Fig. 1). Both protocols were compared using a decision tree, which allows to represent and compare the expected results of each strategy. The decision tree is created from left to right. Both protocols are described:

Protocol A (2006–March 2008) the control group: Patients scheduled for surgery were included in this group. The protocol consisted of conducting a screening based on nasal swabs to determine whether MRSA was present (colonization). If the result was positive then treatment with mupirocin was prescribed (twice a day during a two-week period), with no follow-up verification. In contrast, those who tested negative did not receive the prophylaxis. The night before the surgery all the patients were shaved.

Protocol B (April 2008–June 2009), the intervention group: Patients who had undergone a cardiac surgical procedure in the service. The prophylaxis performed on all patients consisted of applying the same mupirocin ointment and shaving and washing the site with chlorhexidine the night prior to surgery.

The times for applying the two protocols were validated by experts, for this it was agreed with different health professionals (services of preventive medicine, surgery, nursery and internal medicine).

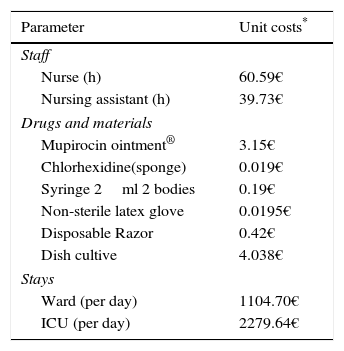

Costs:Table 1 contains the data used in the model. They are presented in Euros 2008 and were obtained from the hospital's analytical accounting management system, COANHyD (contabilidad análitica hospitales y distritos; Andalusian analytical accounting system), except for costs for fungible items, which were obtained from the Purchasing Department, and the cost of drugs, which were obtained through the HUVV's Pharmaceutical Service. Only direct costs were taken into account, no discount rates were applied.

Units costs used in the cost-effectiveness analysis.

| Parameter | Unit costs* |

|---|---|

| Staff | |

| Nurse (h) | 60.59€ |

| Nursing assistant (h) | 39.73€ |

| Drugs and materials | |

| Mupirocin ointment® | 3.15€ |

| Chlorhexidine(sponge) | 0.019€ |

| Syringe 2ml 2 bodies | 0.19€ |

| Non-sterile latex glove | 0.0195€ |

| Disposable Razor | 0.42€ |

| Dish cultive | 4.038€ |

| Stays | |

| Ward (per day) | 1104.70€ |

| ICU (per day) | 2279.64€ |

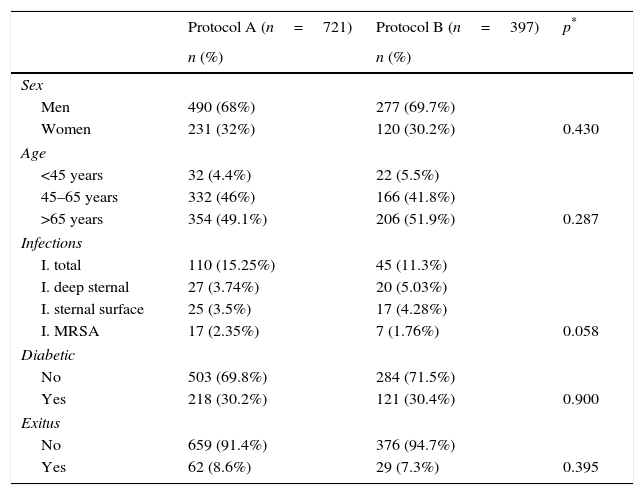

Once approval was obtained from the ethics committee, data was collected by members of the nursing staff who received specific training for this study. This study complied with the ethical principles contained in the Helsinki Declaration and its later modifications (Table 2).

Characteristics of the sample (n=1118).

| Protocol A (n=721) | Protocol B (n=397) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Men | 490 (68%) | 277 (69.7%) | |

| Women | 231 (32%) | 120 (30.2%) | 0.430 |

| Age | |||

| <45 years | 32 (4.4%) | 22 (5.5%) | |

| 45–65 years | 332 (46%) | 166 (41.8%) | |

| >65 years | 354 (49.1%) | 206 (51.9%) | 0.287 |

| Infections | |||

| I. total | 110 (15.25%) | 45 (11.3%) | |

| I. deep sternal | 27 (3.74%) | 20 (5.03%) | |

| I. sternal surface | 25 (3.5%) | 17 (4.28%) | |

| I. MRSA | 17 (2.35%) | 7 (1.76%) | 0.058 |

| Diabetic | |||

| No | 503 (69.8%) | 284 (71.5%) | |

| Yes | 218 (30.2%) | 121 (30.4%) | 0.900 |

| Exitus | |||

| No | 659 (91.4%) | 376 (94.7%) | |

| Yes | 62 (8.6%) | 29 (7.3%) | 0.395 |

Economic evaluation analysis: First, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated=(costs for Alternative B−costs for Alternative A)/(effectiveness B−effectiveness A). Second, to determine the model's robustness a sensitivity analysis was performed modifying the cost for staying in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) (highest unit cost) and the prevalence of MRSA (it was assumed to have a greater impact on the model and due to the higher prevalence in cardiac surgeries).7 Finally, a probabilistic sensitivity analysis was done to evaluate the uncertainty parameter through simulations. Thus, in each simulation a probabilistic distribution was assigned for the beta or normal distribution that fit each parameter. One thousand simulations were processed and an ICER was obtained for each one; calculations were based on data related to cost and incremental effectiveness. MS Excel was used to analyze the data.

ResultsA total of 1118 patients were included (721 in Protocol A and 397 in Protocol B). No statistically significant differences were found in age, sex, diabetes, exitus or length of hospital stay between the two protocols. In the control group the rate of infection was 15.2% (IC95% 12.7–18.0), compared with 11.3% (IC95% 8.3–14.8) in the intervention group. The difference between the two groups is at the edge of statistical significance (p=0.058).

Regarding variables related to admission to the ICU, 82.4% of those in Protocol B were admitted compared to 77.8% of those in Protocol A, a difference that is not statistically significant (p=0.71). The average stay of the intervention group was 4.82 days, compared to 4.93 days in the control group (4.55 days for those in the group that received both screening and treatment; 4.98 days for those who were not screened). It is important to highlight that those included in Protocol A showed significantly higher stays in the ICU (p<0.001).

Cost-effectiveness analysisThe effectiveness detected in the control group was 84.7% of infections averted; for the intervention group it was 88.7%. Thus it can be affirmed that the use of Protocol B represented a decrease of 4% in the total of SSI in cardiac surgery.

The costs derived exclusively from screening and treatment included in Protocol A amounted to 639.96 Euros, while those derived from application of universal treatment in Protocol B came to a total of 1,549.49€. After adding the costs derived from hospitalization etc., the average cost per patient in Protocol A came to 26,597.87€. For Protocol B, however, that cost amounted to 25,297.63€, representing a total savings per patient of 1300.24€. Protocol B proves to be more effective and at a lower cost, yielding an ICER of −32,506€, indicating that we have found an efficient intervention which produces savings to the health system.

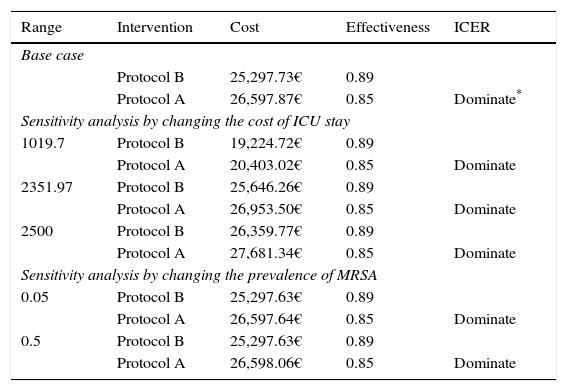

When the prevalence of MRSA and the cost of staying in the ICU were modified in the sensitivity analysis, both scenarios revealed Protocol B to be more efficient and less costly than Protocol A. Finally, the probabilistic sensitivity analysis that was performed also confirmed the difference in favor of Protocol B, which was more effective and less costly than Protocol A (Table 3).

Cost-effectiveness of prophylactic protocols, base case and sensitivity analysis.

| Range | Intervention | Cost | Effectiveness | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base case | ||||

| Protocol B | 25,297.73€ | 0.89 | ||

| Protocol A | 26,597.87€ | 0.85 | Dominate* | |

| Sensitivity analysis by changing the cost of ICU stay | ||||

| 1019.7 | Protocol B | 19,224.72€ | 0.89 | |

| Protocol A | 20,403.02€ | 0.85 | Dominate | |

| 2351.97 | Protocol B | 25,646.26€ | 0.89 | |

| Protocol A | 26,953.50€ | 0.85 | Dominate | |

| 2500 | Protocol B | 26,359.77€ | 0.89 | |

| Protocol A | 27,681.34€ | 0.85 | Dominate | |

| Sensitivity analysis by changing the prevalence of MRSA | ||||

| 0.05 | Protocol B | 25,297.63€ | 0.89 | |

| Protocol A | 26,597.64€ | 0.85 | Dominate | |

| 0.5 | Protocol B | 25,297.63€ | 0.89 | |

| Protocol A | 26,598.06€ | 0.85 | Dominate | |

| Intervention | Cost median (range) | Effectiveness median (range) | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic sensitivity analysis | |||

| Protocol B | 25,562.04€ (40,401.97–2051.10) | 0.89 (0.85–0.92) | |

| Protocol A | 26,598.37€ (33,122.88–1236.13) | 0.85 (0.82–0.87) | Dominate |

This study evaluates the cost-effectiveness of the universal prophylaxis with mupirocin as a preventive measure against SSI in cardiac surgery. The study provides arguments to improve patient safety in cardiac surgery, in a field which the published studies are limited.14,19

Current trends underscore the importance of economic evaluations as tools to assist in making decisions based not only on health results, but on costs incurred as well. The systematic use of this technique can contribute to a more efficient use of the limited resources available in the health system, taking into account the opportunity cost of choosing one intervention while foregoing another.22

There are limitations of this study. The use of only one facility limits the ability of generalizing the results to other cardiac surgery sites. A second limit is the lack of information regarding type and duration of antibiotic prophylaxis for surgical interventions that might have had a significant role in the development of S. aureus/nosocomial infections.

The results of this study confirm that as a preventive measure against SSI in cardiac surgery the universal prophylaxis with mupirocin is not only cost effective when compared with the strategy to selectively treat patients according to their screening results, or the strategy of not treating any patient, but that it is also a dominant situation strategy. It is less expensive and more effective. The authors were only able to identify two studies with goals similar to ours, and the results of both resembled ours.14,19 These papers demonstrated that mupirocin application reduces length of stay. The sensitivity analyses proved that changes in surgical site infection, effectiveness and costs of the application of mupirocin are shown as a cost-effective strategy.

Our results regarding the logical decrease of stays in the hospital and ICU as a consequence of lower SSI are also similar to those reflected in the literature.7,23–25

According to this study's results, the “universal” treatment strategy aimed at reducing the number of SSI is cost-effective. Furthermore, this antibiotic, in addition to reducing the number of SSI due to MRSA and other microorganisms, as has been established in a majority of international studies and guides, such as those published by the CDC, has the advantages of being easy to apply, not requiring any specialized knowledge, and costing less.24,26 Even more importantly, it appears that this antibiotic has a low rate of resistance,9,10 which would permit its broader, though always controlled, use.

Several different policies centered on reducing infections related to the provision of health care services have been implemented in recent years, for example, the WHO's “Bacteriemia Zero Campaign”. Campaigns such as this one increase the awareness of surgical staff members on inadequate procedures. In this sense, the majority of health professionals were the same for both protocols, previous learning, structure, safety culture, training and behavioral changes could overestimates the effectiveness of the protocol B, Since this fact could be interpreted as limiting the study's final results, different sensitivity analyses were conducted to diminish uncertainty.

We believe that further research along these lines is necessary to permit the reduction of SSI, more rational drug management, and more efficient health actions.

Conflict of interestNo financial resources were used to produce this manuscript and the authors have no conflict of interest involving its contents.

To Rubén Alba Ruiz for his assistance in the bibliographical search, to Leticia García for her help in obtaining results, to José Miguel Garcia for his constructive criticism in presenting this work as a dissertation, and to Antonio García Rodríguez and Carlos Muñoz Bravo (Department of Preventive Medicine. University of Malaga, Malaga, Spain) for their comments and help.

This work was awarded a prize from the Royal Academy of Medicine for Eastern Andalusia (the Colegio Oficial de Médicos prize) and have also been incorporated into the Andalusian School of Public Health's (Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública) curriculum for its Master's degree in Public Health and Health Management.