Asthma is a heterogeneous disease that often coexists with type 2 inflammatory (T2i) conditions in many individuals with severe asthma, leading to heightened exacerbations that diminish their quality of life (QoL). Despite this, there is a noticeable scarcity of QoL assessment tools specifically designed for individuals with T2i-related asthma.

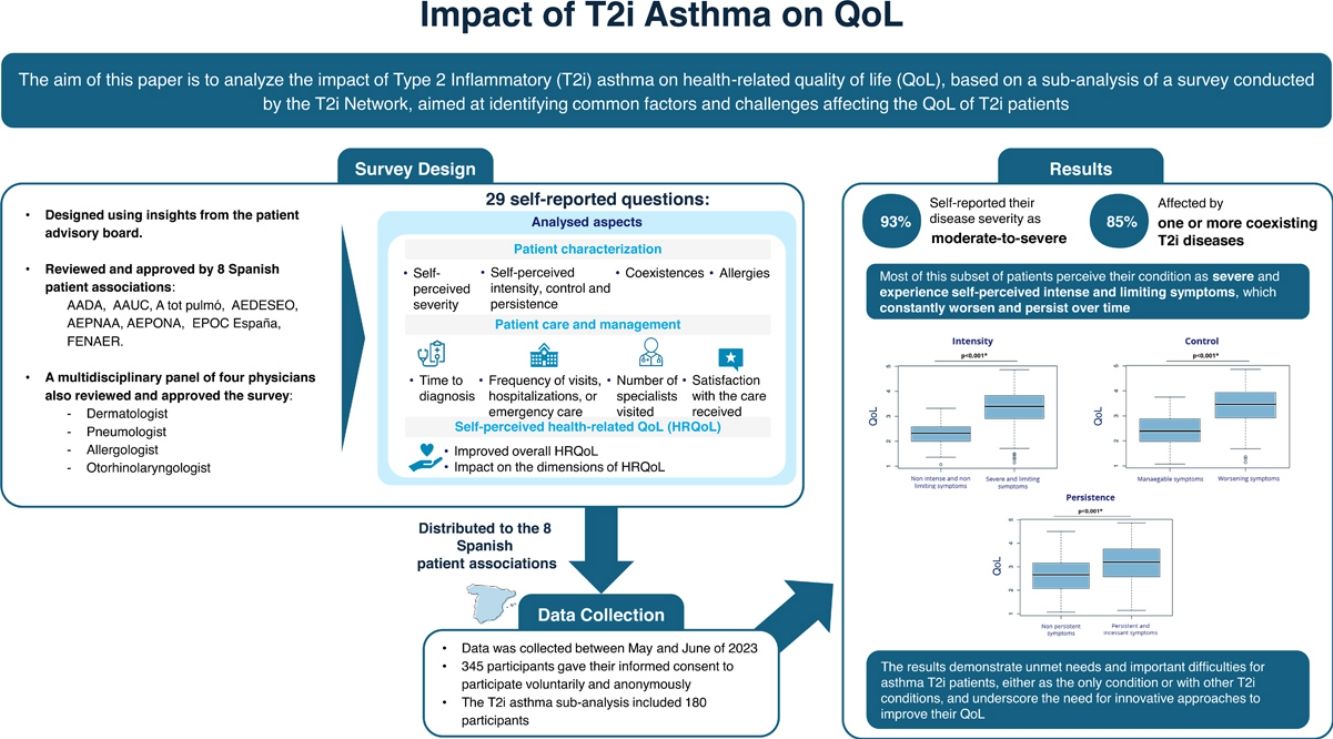

ObjectivesTo analyse the asthma subset of T2i patients, derived from a survey conducted by the patient-driven T2i Network Project, aimed at identifying common drivers and challenges related to the QoL of T2i patients.

Material and methodsAn anonymous online survey was distributed through eight Spanish patient associations. It comprised 29 questions about the patient's sociodemographic characteristics and several self-reported questions about the diagnosis, QoL measures, the severity of the disease, use of healthcare resources, and quality of care.

ResultsThe T2i asthma sub-analysis included 180 participants; 93% self-reported their disease severity as moderate-to-severe, 85% affected by one or more coexisting T2i diseases. An increase in the self-perceived severity was associated with higher self-perceived intensity, lack of control, and persistence of symptoms, with a stronger impact on total QoL. Asthma participants expressed a great impact on all the measured dimensions of the QoL.

ConclusionsThe results demonstrate unmet needs and important difficulties for asthma T2i patients, either as the only condition or with other T2i conditions, and underscore the need for innovative approaches to improve their QoL. Most of this subset of patients perceive their condition as severe and experience self-perceived intense and limiting symptoms, which constantly worsen and persist over time.

El asma es una enfermedad heterogénea que coexiste con condiciones inflamatorias tipo 2 (T2i) en individuos con asma grave, lo que provoca exacerbaciones y disminuye su calidad de vida (CdV). Sin embargo, existe una falta de herramientas específicas para evaluar la CdV en pacientes con asma relacionada con T2i.

ObjetivosAnalizar el subconjunto de pacientes con asma T2i, derivado de una encuesta del proyecto T2i Network, con el fin de identificar factores comunes y desafíos relacionados con la CdV de estos pacientes.

MétodosSe distribuyó una encuesta en línea anónima a través de ocho asociaciones de pacientes españolas. La encuesta incluyó 29 preguntas sobre características sociodemográficas y varias preguntas autoinformadas sobre diagnóstico, medidas de CdV, gravedad de la enfermedad, uso de recursos sanitarios y calidad de la atención.

ResultadosEl subanálisis de asma T2i incluyó a 180 participantes, de los cuales el 93% reportó una enfermedad moderada o grave, y el 85% padecía una o más enfermedades T2i coexistentes. Un aumento en la gravedad autopercebida se asoció con mayor intensidad de síntomas, falta de control y persistencia, afectando la CdV total. Los pacientes con asma mostraron un gran impacto en todas las dimensiones medidas de la CdV.

ConclusionesLos resultados evidencian dificultades y necesidades no cubiertas para los pacientes con asma T2i, ya sea como única condición o coexistiendo con otras T2i, y resaltan la necesidad de enfoques innovadores para mejorar su CdV. La mayoría percibe su enfermedad como grave, con síntomas persistentes que empeoran con el tiempo.

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease, usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation, accompanied by signs and symptoms such as wheezing, shortness of breath, cough, and/or chest tightness. Patients can experience episodic flare-ups (exacerbations) that may be life-threatening and carry a significant burden. Left uncontrolled, it represents an extremely debilitating disease, causing recurring disturbance and fatigue, with limitations in the patient's quality of life (QoL).1,2 Currently, there is growing recognition that asthma is part of a multimorbidity syndrome,3–5 and a significant percentage of asthma patients report symptoms of coexisting type 2 inflammatory (T2i) diseases, such as eczema/atopic dermatitis (AD), chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis (CRwNP), eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), allergic rhinitis (AR), or food allergies.5–8 Asthma linked to type 2 inflammation is a distinct phenotype associated with T2 inflammation-related disorders, characterized by high blood eosinophil levels or increased fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), particularly in adults with allergic asthma on inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).2,5

The coexistence of asthma and these T2i conditions is common and may be explained by a shared pathological mechanism driven by an allergen-specific T-helper 2 (Th2) cells responses that produce type 2 cytokines (interleukin [IL]-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13), and that lead to the accumulation of high numbers of eosinophils in the airway wall.2,9

In asthma patients due to T2i, a cycle involving increased exhaled nitric oxide fraction (FeNO) (a marker of airway inflammation), worsening asthma control, lung function decline, and increased susceptibility to asthma exacerbation have been described, leading to reduced QoL.1,2,9–15 Furthermore, although the prevalence of coexisting T2i conditions in asthma patients, limited data exist regarding their impact on asthma outcomes.5

Approximately 50–70% of asthma patients have T2i asthma,5,16,17 representing a serious global health concern and creating a substantial clinical and economic burden.5

It is well recognized that asthma management focuses on improving QoL, which includes symptom severity, frequency, and intensity of exacerbations, as well as lung function.2 Although GINA and POLINA guidelines recommend assessing multimorbidity and identifying factors that contribute to asthma symptoms and exacerbations – some of which are also faces of the T2i prism – such as rhinitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and CRwNP – in the investigation and management of the disease, GINA does not specifically recommend identifying the QoL of this asthma phenotype.2,18

In fact, most used validated QoL questionnaires are disease-specific QoL instruments, such as the Asthma QoL questionnaire-Juniper (AQLQ-J), the Asthma Control Test™ (ACT) and the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ).19,20

In general, they are self-completed questionnaires, typically short, most used to measure the health status or health-related QoL (HRQoL) of a patient before and after an intervention. While the AQLQ-J include patient's exposure to environmental stimuli as a special component affecting their QoL and emotional functional problems measurement.20,21 Both the ACT and ACQ emphasize symptoms and functional status rather than how these affect the patients’ subjective perceptions of asthma's effect on their day-to-day QoL. They do not consider other factors that could impact QoL in asthma patients, including coexisting conditions like gastro-oesophageal reflux and rhinosinusitis, which likely play a role in determining QoL in patients with asthma.22 According to our understanding, limited data on patient's experiences, perspectives, and current management of T2i diseases have been published.23

Eight patient associations in Spain joined forces to establish the T2i Network to amplify patients’ voices, foster the development of innovative care strategies, and identify common drivers and challenges in QoL among patients with T2i diseases. The T2i Network initiated a project that created a survey aimed at identifying the common drivers and challenges affecting the QoL of patients with T2i diseases.23

This paper presents a sub-analysis focused on asthma patients, with or without other coexisting T2i conditions. The objective is to explore the impact on HRQoL among patients with T2i asthma, identify unmet needs, and examine patient-perceived barriers to care. We hypothesized that patients with T2i asthma experience a substantial burden on their HRQoL, influenced by self-perceived symptom severity, persistence, and control, as well as by gaps in current care pathways.

Material and methodsDesign and validation of the surveyThe survey has been described previously by our group.23 Briefly, convenience sampling was used to conduct an anonymous online survey for this project, and was implemented using EUSurvey, an online platform of the European Commission designed for managing surveys, text, and multiple-choice questions.

Data collectionData was collected between May and June of 2023. The survey was distributed through eight Spanish patient associations (Supplementary S1). The project's objectives were communicated to participants, who gave their informed consent to participate voluntarily and anonymously.

Survey design.The survey was designed based on the insights gathered from the patient advisory board and reviewed and approved by the Spanish patient associations and a multidisciplinary panel consisting of four physicians. An English version may be found in the Supplementary Appendix.

Survey descriptionThe survey consisted of 29 questions about the participant's sociodemographic features and a series of self-reported multiple-choice or rating scale questions, including diagnosis, QoL measures, self-perceived disease severity, healthcare resource utilization, and quality of care, detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

Patients includedThis manuscript presents a sub-analysis of a broader survey targeting individuals with T2i conditions. For this specific analysis, we included only participants aged >18, residing in Spain, who self-reported a diagnosis of asthma, either alone or in combination with other T2i diseases. Details regarding the presence of allergies were provided. However, it was not characterized as a T2i pathology since the origin of the allergy was uncertain and potential patient confusion between food allergies and intolerances. Thus, allergies were included as descriptive information.

Statistical analysisRStudio (R v.4.1.0) was used for all descriptive and inferential statistical analyses (i.e., mean, standard deviation (SD)).

Total QoL (TQoL), a per-patient QoL composite score, was produced by averaging QoL factors that were scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The psychological impact resulting from the mean of the factors included was combined into a single variable.

Likewise, satisfaction with treatment efficacy and treatment-related secondary effects were grouped into a single variable.

The Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test and the post-hoc Dunn test were utilized to analyse Likert scale data for multiple comparisons of severity groups. Parametric tests were employed for analysing TQoL data and individual QoL domains. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was conducted to examine potential differences in TQoL among self-perceived severity groups, followed by a pairwise t-test for post-hoc analysis to identify specific groups with significantly divergent TQoL.

The impact of self-perceived symptom intensity, lack of control, and persistence on QoL, was conducted using the Kruskal–Wallis, Dunn test, ANOVA using a pairwise t-test.

In all instances, significance was assessed at a threshold of p<0.05, with adjustments made for multiple testing using the Bonferroni correction method if convenient.

Ethical concernsThe Local Ethics Committee of a hospital in Spain approved the study (HUFA/23-79).

Given that the survey was completely anonymous and that respondents could not be identified in any way, the ethics committee approved the exemption of informed consent.

ResultsPatient characteristicsThe survey collected information from 345 participants with a T2i condition, being asthma diagnosed in 180 of them (n=180/345, 52%). The mean age was 42±14 years, of which 71% were female (Table 1). A total of 85% of patients stated having one or more coexisting T2i conditions, 54% of them diagnosed with ≥2 different T2i conditions, while 15% did not have any other T2iD. AR, AD and CRSwNP were the most frequent T2i pathologies that coexisted with asthma.

Overview of asthma patient characteristics (asthma alone or in coexistence with other T2i conditions).

| T2i asthma patient characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Total sample | N=180 |

| Median age (range) | 42 (18–71) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 71% (n=128) |

| Male | 28% (n=51) |

| Not answered | 1% (n=1) |

| Coexisting T2iD | |

| Yes | 85% (n=153) |

| No | 15% (n=27) |

| Coexistent T2iD* | |

| DA | 52% (n=80) |

| AR | 57% (n=87) |

| EoE | 16% (n=25) |

| CRSwNP | 29% (n=45) |

| SCU | 10% (n=16) |

| ICU | 3% (n=5) |

| N-ERD | 10% (n=16) |

| COPD | 7% (n=11) |

| Allergy | |

| Yes | 69% (n=124) |

| No | 11% (n=27) |

| Type of allergy** | |

| Food | 57% (n=71) |

| Environmental | 81% (n=100) |

| Drug | 32% (n=40) |

| Self-perceived severity | |

| Mild | 7% (n=12) |

| Moderate | 38% (n=69) |

| Severe | 55% (n=99) |

T2iD: type 2 inflammatory disease; DA, atopic dermatitis, asthma; AR, allergic rhinitis; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; CRSwNP, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps; SCU, spontaneous chronic urticaria; ICU, induced chronic urticaria; N-ERD: NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Of the overall number of patients, 69% reported having some type of allergy, of whom 81% had environmental allergies, 71% had food allergies, and 32% had drug allergies.

The self-perceived severity of the disease among participants was mild for 7%, moderate for 38%, and severe for 55% (Table 1).

Most patients experienced intense and limiting symptoms (intensity), which constantly worsened (control), persisted, and did not disappear (persistence) (Fig. 1A). When analyzing the possible relation between self-perceived symptoms and self-perceived disease severity, it was observed that the self-perceived intensity, lack of control, and persistence of symptoms increased in a statistically significant way (p<.001) as the self-perceived severity increased (Fig. 1B).

QoL impact of asthmaWhen asked how asthma affected the different QoL domains, 47–83% of participants indicated a rating of ≥3 on each of the QoL dimensions (Fig. 2A). This suggests that their QoL was frequently and seriously impacted.

Unpredictability and anxiety were the most severely affected categories of QoL, with 83% and 79% of patients reporting a negative impact, and 60% and 50% of responders expressing a QoL impact score of ≥4, respectively. These findings indicate that participants were frequently or always aware of potential illness triggers, with a significant psychological burden of the condition on patients.

Furthermore, 76% said that physical limitations affected them frequently or very frequently, making it difficult for them to carry out regular tasks and enjoy pleasurable activities. Additionally, 76% reported impaired sleep quality, referring to a rather poor/poor sleep quality.

Patients’ everyday activities were regularly or very frequently disrupted by the side effects of drugs used to treat asthma, either alone or with other coexisting T2i disorders, indicating a low degree of satisfaction with existing therapies, being reported by 74% of them.

The TQoL score was found to be more impacted by asthma patients with higher self-perceived severity than by patients with mild or moderate severity (Fig. 2B). The mean TQoL for severe patients was 3.39, which was statistically different from the mean for participants in the other severity groups (2.28 for mild and 2.78 for moderate participants; pairwise comparisons: severe vs. mild p<.001, severe vs. moderate p<.001). Like how increased severity affects HRQoL, the self-perceived intensity, lack of control, and persistence of symptoms significantly impact patients’ HRQoL (p<.001, p<.001, and p<.001, respectively) (Fig. 2C).

Patients who perceive their condition as more severe experience a significantly greater impact on all their HRQoL domains, as compared to those with mild symptoms (Supplementary Fig. S1).

According to the differences in HRQoL based on the level of symptom self-perceived control, intensity and persistence, it was seen that patients experiencing more difficult-to-control symptoms experienced a significantly greater impact on all aspects of their HRQoL compared to those with easier-to-control symptoms, and patients experiencing persistent symptoms significantly impacted most aspects of their HRQoL, more than those with less persistent or episodic symptoms, respectively.

Healthcare resource utilization managementPatients with asthma sought care from a wide range of specialties. The most frequent were allergology, primary care, pulmonology, and dermatology, having received visits from 83%, 81%, 61% and 46% of participants, respectively. Twenty five percent of patients visited ≥5 different specialists since the onset of their symptoms (Fig. 3A). In addition, the percentage of patients who visited a higher number of healthcare specialists increased significantly according to the self-perceived severity, with 75% of the severe patients visiting ≥4 healthcare specialists, as shown in Fig. 3B.

Regarding healthcare resource utilization, the survey revealed that, during the last year, 55% of patients with asthma visited the emergency department at least once, and 9% did so more than five times. Additionally, 15% were hospitalized at least once, and 17% had one or more scheduled medical visits per month (Table 2).

Frequency of healthcare resource use in the last year in the overall T2i asthma population.

| Frequency of healthcare resource use in the last year in the overall T2i asthma population (N=180) | |

|---|---|

| Scheduled visits | |

| None | 5% (n=9) |

| Once a year | 18% (n=32) |

| Once every 6 months | 27% (n=49) |

| Once every 3 months | 33% (n=60) |

| Once every month | 9% (n=16) |

| More than once a month | 8% (n=14) |

| Emergency visits | |

| None | 45% (n=81) |

| Between 1 and 3 times | 39% (n=70) |

| Between 3 and 5 times | 7% (n=12) |

| More than 5 times | 9% (n=17) |

| Hospitalizations | |

| None | 86% (n=154) |

| Between 1 and 3 times | 10% (n=18) |

| Between 3 and 5 times | 1% (n=1) |

| More than 5 times | 4% (n=7) |

Regarding the frequency of medical visits according to self-perceived severity, resource utilization escalates with the degree of self-perceived severity. Among those classified as self-perceived severe cases, 16% made over five visits to the emergency department within the past year, 7% experienced hospitalizations exceeding five occurrences, and 41% maintained scheduled medical appointments every 3 months. Across all three scenarios, the differences were statistically significant (p=0.0017, p=0.003, and p=0.001, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S2). These findings suggest that asthma patients were typically managed by multiple specialists over their clinical journey.

Patient perception of healthcare qualitySignificantly, 44% reported that they did not receive enough information about their disease and treatment, and 71% felt they were not receiving solutions to improve their QoL (Fig. 4A and B). In addition, 54% reported a lack of coordination between specialists and primary care, even though 60% highly assessed the understanding and listening of primary care, as shown in Fig. 4C.

DiscussionThis article presents initial findings from a sub-analysis of T2i asthma patients, either alone or in coexistence with other T2i conditions, as part of a broader survey on T2i conditions. The survey aimed to enhance understanding of patients’ perspectives on the burden of T2i diseases and their impact on QoL, identify challenges and potential solutions for improving patient care, and address unmet needs. It includes questions designed to assess the illness's impact on common asthma QoL dimensions, with a focus on unpredictability and planning difficulties due to their critical importance for these patients.

Although the majority of asthma cases are associated with T2i, it is important to acknowledge that T2i pathogenesis is not present in all asthma phenotypes. In this survey – and specifically in the subset of respondents with asthma – all cases were assumed to represent T2i phenotypes. While this assumption may represent a limitation, it reflects current clinical challenges due to the absence of a standardized biomarker-based definition for T2i asthma in routine practice.24 Nevertheless, existing evidence indicates that approximately 70% of asthma cases are driven by T2i mechanisms,5,16,17 supporting the rationale for this classification approach in the context of our study.

The study reveals that T2i asthma significantly impacts patients’ QoL, affecting psychological, social, occupational, and educational aspects. This is often exacerbated by multiple coexisting T2i conditions and a perceived lack of coordination between different specialties and primary care. The findings highlight the need for a comprehensive and coordinated approach to T2i asthma treatment that addresses both physical symptoms and the psychological and social well-being of patients.

Different studies have examined the management of patients with T2i conditions and their coexistence.25–29 Even though the GINA guidelines suggest that T2i phenotypes should be identified, since targeted therapy is more likely to be successful in patients with similar underlying pathobiological features,2 most of the QoL questionnaires do not consider other factors that could impact the QoL in T2i asthma patients, such as coexisting conditions like gastro-oesophageal reflux and rhinosinusitis.22

The survey findings indicate that T2i asthma patients frequently have coexisting diseases, which confirms the substantial burden in terms of the number and severity of T2i conditions.2,22,30 AR, AD and CRSwNP are the most frequent T2i pathologies that coexist with asthma among our participants, which matches with the findings that among CRSwNP patients, asthma is highly prevalent, and the presence of nasal polyps is strongly associated to severe asthma. In this context, it has been recommended that every patient with CRS gets at least one systematic evaluation for asthma and allergy preferably by a validated questionnaire, and if at risk for asthma, spirometry to assess lung function.26 In addition, previous studies have demonstrated that asthma, AD, and CRSwNP are inflammatory conditions found in subgroups with overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms, accounting for their often simultaneous occurrence.25 Furthermore, people with allergic asthma can commonly also have concomitant AR, and patients with CRSwNP might also present comorbid asthma.28 By contrast, despite their coexistence and common pathophysiology, these T2i diseases are often managed as single entities, leading to inadequate disease control, persistent symptoms, and poor QoL.23,28

The study shows that most of the T2i asthma patients (either alone or in coexistence with other T2i conditions), perceived their condition as severe and encountered persistent, intensifying, debilitating symptoms that constantly worsened and significantly restricted daily activities. These findings differ from those described in the T2i Network Project.23 Higher self-perceived intensity, lack of control, and persistent symptoms are linked to higher self-perceived severity, which also has a greater influence on all QoL dimensions, with unpredictability, anxiety, physical limits, sleep disturbance, and treatment dissatisfaction being the most affected. Heightened self-perceived severity correlated with increased self-perceived intensity, lack of control, and persistence of symptoms, as well as a more pronounced impact across all dimensions of QoL. This is not surprising and may align with the notion that asthma patients exhibiting elevated expression of TH2 cell cytokine gene expression experience more severe asthma.9 According to GINA guidelines, T2i is found in most people with severe asthma,2 and it has been described as a cycle of lung function decline and asthma exacerbations driven by T2i in asthma, which could impair QoL.1,2,9–15,31

In addition, these findings match the data in the EUFOREA white paper,25 which identified the previously described QoL issues as widespread among T2i patients and with those reported by the results of the T2i Network Project.23

It is known that living with the unpredictability of asthma flares can cause increased stress, anxiety, and fear of future exacerbations.32 Unpredictable breathlessness has been shown to heighten intense feelings of anxiety, fear, and distress, implying a reinforcement loop between unpredictable breathlessness.33 According to different studies, anxiety disorders and depression are more prevalent among people with asthma and could be associated with poorer symptom control, and asthma-related QoL. Patients with trouble differentiating asthma symptoms from anxiety or depression should be referred to specialized psychiatrists.2

As described in previous studies, many patients indicated that their asthma symptoms had caused to experience shortness of breath and night-time awakenings, and rescue inhaler use was generally high.34 In addition, they said that asthma negatively impacts their daily life and keeps them from accomplishing daily tasks,34 as our data reveal. Guidelines ought to urge clinicians to obtain a comprehensive sleep history and suggest inquiring about nocturnal asthma symptoms, as managing nocturnal symptoms may result in better sleep. A cross-sectional, observational real-world survey found a correlation between the increase in disability and the impact on sleep disturbance.35

Another finding of our survey showed a considerable rate of Healthcare Resource use among T2i asthma patients and the high number of different specialists visited. For example, 25% have consulted ≥5 specialists since the onset of their symptoms. Our data also suggests that as the disease progresses, patients are more likely to seek care from a larger number of specialists, as previously seen for T2i diseases.23 Furthermore, most participants expressed dissatisfaction with the solutions to improve their QoL, and over half perceived a lack of coordination between specialists and primary care. These findings indicate not only that T2i asthma patients are typically managed by multiple specialists over their clinical journey, but also may indicate a deficiency in a successful multidisciplinary approach, highlighting the need for stronger collaboration between general practitioners and specialists, to potentially decrease healthcare utilization rates, enhance the efficiency of the healthcare system, and improve patient QoL. The results match with the results of a qualitative study done by EUFOREA in seven participating academic centers in Europe,25 with patients suffering from severe chronic T2i (asthma, CRSwNP, and/or AD) showed shortcomings of current care pathways, delayed diagnoses, limited consultation time, and lengthy waiting lists, which hindered timely care during exacerbations. Overall, our results suggest that improved patient-physician communication may enhance T2i asthma management and results, highlighting the need for a trained and coordinated multidisciplinary team of HCPs for T2i patients.

In summary, our results highlight the need for a multidisciplinary approach to managing patients with T2i asthma, either as the only condition or coexisting with other T2i diseases. This approach not only has the potential to enhance patient outcomes and QoL but also to reduce healthcare resource utilization by expediting diagnosis, optimizing treatment plans, and minimizing specialist visits.

According to the conclusions of the T2i Network survey, existing QoL assessment tools for various pathologies lack consideration for concurrent diseases. A validated tool is necessary to measure QoL in these patients, guiding the medical community in assessing their true QoL impact and devising effective patient management approaches. This project lays the foundation for such a tool's development, aiming to enhance outcomes and QoL for patients with T2i diseases through future research.

This study has several strengths; including the fact that the survey was validated by an advisory board, reviewed by a multidisciplinary expert panel, and distributed to patients from eight distinct patient associations. The sample offers comprehensive and detailed information on T2i asthma patients. Despite this, a possible limitation was that participants came from patients’ associations, probably being committed and self-conscious patients and having suffered more negative experiences, and a bias in the response could not be excluded. Then, the sample does not fully represent all T2i asthma patients in Spain. Another limitation is that the survey design did not enable us to find a direct correlation with the specific nature of asthma in patients with other T2i disorders. Importantly, the survey lacked data on non-T2i comorbidities that could independently affect QoL. This limitation prevented adjustment for possible confounding effects. Additionally, it is important to note that all the results rely on self-perception or self-reporting by the patients.

ConclusionIn conclusion, this study shows that the medical community requires a validated approach to assessing the QoL of individuals with T2i asthma. In addition to providing guidelines for determining the genuine impact of these disorders on the QoL of those affected, the holistic tool should help develop innovative patient treatment techniques that are advantageous to patients.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processNo generative AI tools were used in the preparation of this manuscript.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, and/or publication fees related to this article. The published work was supported by Sanofi Spain. The funder was not involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflicts of interestThis publication is the result of collaborative research performed between patients, doctors and healthcare quality experts with the coordination and supervision of Alira Health Company.

IO declares to have received honoraria for participating as a speaker in meetings sponsored by AstraZeneca, Boehringuer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, and Novartis and as a consultant for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKlein, Puretech and Sanofi. He has also received financial aid from AstraZeneca, Bial and Chiesi for congress attendance and has received grants from Sanofi for research projects. IA declares to have received honoraria for consultancy and conferences from AstraZeneca, Viatris, Roche, Sanofi, GSK, MSD, Menarini, Salvat, Galenus Health, Olympus, Metronic, and Novartis. VR declares to have received honoraria as a consultant for Biocryst and CSL Behring and Sanofi, and received financial aid from GlaxoSmithKlein for congress attendance. EG declares to have received honoria for consultancy, conferences and advisory boards from Abbvie, Almirall, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ariadna Castillo and Malena Águila from Alira Health for their assistance in medical writing support, which was funded by Sanofi Spain.