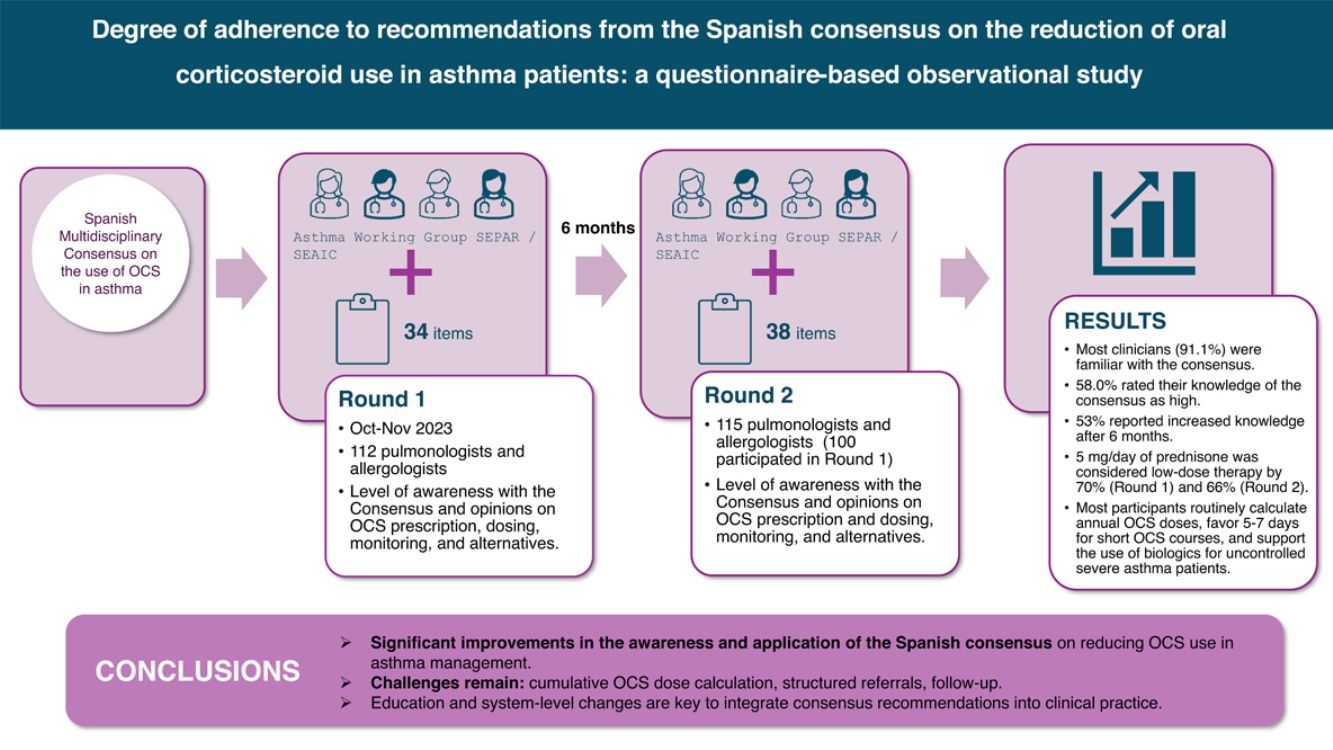

The Spanish consensus on the reduction of oral corticosteroid (OCS) use in asthma management was recently published to address the issue of OCS overuse in this area. This study evaluates the degree of awareness and implementation of this consensus by healthcare professionals.

MethodsA longitudinal study was conducted with a survey completed by pulmonologists and allergists in 2 rounds conducted 6 months apart. Key metrics included OCS prescribing rates, adherence to recommendations, and other clinician-reported practices.

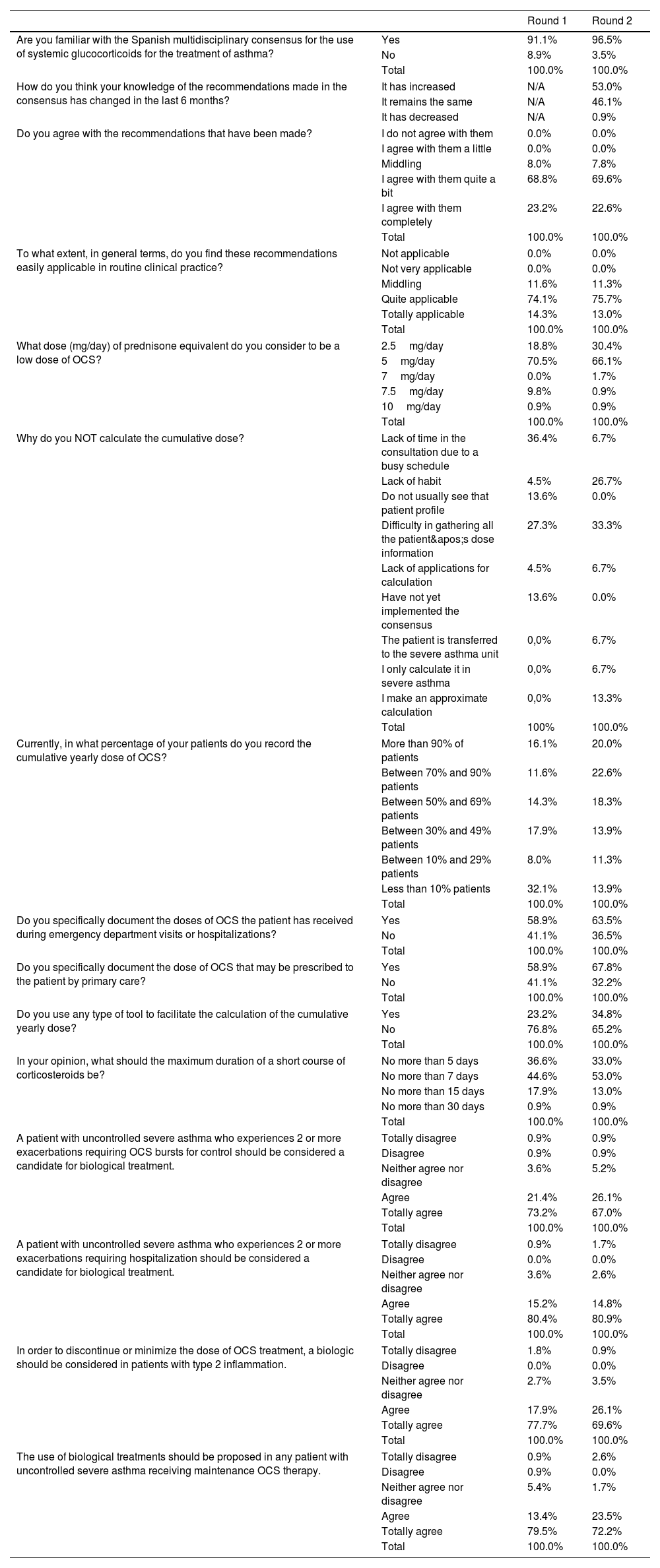

ResultsBoth rounds were completed by 112 and 115 participants, respectively, with equal representation from allergists and pulmonologists. Most (91.1%) were familiar with the consensus, and 58.0% rated their knowledge as high. Fifty-three percent reported increased knowledge after 6 months. Regarding OCS dosing, 70.5% in the first round and 66.1% in the second round considered 5mg/day of prednisone to be low-dose therapy. A majority routinely calculated annual OCS doses, with a notable rise in the use of digital tools for dose calculations. Most clinicians favored 5–7 days for short OCS courses and supported the use of biologics for patients with uncontrolled severe asthma on maintenance OCS.

ConclusionsThese findings suggest a notable reduction in OCS use and improved adherence to asthma management guidelines following the publication of the Spanish consensus. Repeated educational interventions appear effective in modifying prescribing behaviors and optimizing asthma care.

Con el fin de abordar el problema del uso excesivo de corticosteroides orales (OCS) en el tratamiento del asma, recientemente se publicó el consenso español sobre la reducción de OCS en el asma. Este estudio tiene como objetivo evaluar el grado de conocimiento e implementación de dicho consenso por los profesionales de la salud.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio longitudinal mediante 2 rondas de una encuesta, cumplimentada por neumólogos y alergólogos con un intervalo de 6 meses. Se evaluaron métricas clave como las tasas de prescripción de OCS, la adherencia a las recomendaciones y otras prácticas reportadas por los clínicos.

ResultadosLas 2 rondas fueron completadas por 112 y 115 participantes, respectivamente, con igual representación de alergólogos y neumólogos. El 91,1% conocía el consenso, y el 58,0% evaluó su conocimiento como alto. El 53% reportó un aumento en su conocimiento tras 6 meses. En cuanto a las dosis de OCS, el 70,5% en la primera ronda y el 66,1% en la segunda definieron 5mg/día de prednisona como dosis baja. La mayoría calculaba de forma rutinaria la dosis anual de OCS, con un aumento notable en el uso de herramientas digitales para ello. La mayoría consideró adecuado un tratamiento corto de 5 a 7 días con OCS y respaldó el uso de biológicos en pacientes con asma grave no controlada en tratamiento de mantenimiento con OCS.

ConclusionesEstos resultados evidencian una reducción notable en el uso de OCS y una mejora en la adherencia a las guías de manejo del asma tras la publicación del consenso español. Las intervenciones educativas continuas parecen ser efectivas para modificar los comportamientos de prescripción y mejorar el tratamiento del asma.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory condition of the respiratory tract characterized primarily by bronchial hyperresponsiveness and variable airflow obstruction.1 Globally, around 400 million people suffer from asthma,2 with nearly 2 million adults affected in Spain (over 5% of the population).3,4 Approximately 5%–10% of asthma patients are diagnosed with severe asthma,5 which is associated with higher morbidity, increased healthcare costs, and more frequent exacerbations.6–8 National and international guidelines recommend a stepwise therapeutic approach to enhance asthma control according to disease severity and response.9,10 This strategy aims to minimize the risk of mortality, decline in pulmonary function, exacerbations, and treatment-associated adverse effects (AEs).10,11 However, despite the framework set by these guidelines and the availability of effective therapies, a significant proportion of patients still have uncontrolled asthma.12 This is mainly attributed to poor adherence to maintenance therapy, undertreatment, improper inhaler technique, overuse of relief medications, and the presence of comorbidities.13

Oral corticosteroids (OCS), which are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs, are commonly used as part of the therapeutic arsenal for the treatment of asthma and other inflammatory conditions.14 Although OCS have been a mainstay in the treatment of uncontrolled asthma for several decades,15 their use is associated with significant AEs, including osteoporosis, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, cataracts, sleep apnea, depression and anxiety, type 2 diabetes, weight gain, renal or adrenal insufficiency, and infectious complications, including sepsis and pneumonia.16–18 Regardless of guidelines recommending long-term, low-dose OCS only for the management of the most advanced stages of asthma,10,19 their use remains prevalent. A study published in 2020 estimated that over 30% of patients with severe asthma in Spain used OCS regularly.20

Although evidence on the optimal OCS treatment regimen is scarce,21 recent advances in biological therapies have shown promise in reducing the need for OCS while lowering exacerbation rates in severe asthma.22,23 This has led to updated guidelines recommending these therapies for patients whose asthma remains uncontrolled despite high-dose inhaled therapies, in order to achieve control and reduce OCS use and the associated risks.24 Consequently, in 2022, a group of specialists in severe asthma published the Spanish Multidisciplinary Consensus on the use of OCS in asthma.25 This consensus was developed by a Delphi process involving 48 experts, including allergists and pulmonologists, and offers scientifically supported recommendations to reduce OCS use and manage related AEs. Although this document could serve as a valuable guide in clinical settings where OCS use still needs to be optimized, little is known about its real-world implementation in routine clinical practice.

For this reason, the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR), in collaboration with the Spanish Society of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (SEAIC), recently launched a questionnaire-based initiative among asthma specialists to assess the impact and degree of implementation of the recommendations derived from this consensus in Spain. The results from the first round of the study have already been published.26 Here, we report the findings from a second round of evaluation conducted 6 months after the initial survey, comparing the results of both rounds to assess progress and challenges in applying the consensus recommendations in clinical practice.

MethodsParticipants were recruited via email invitations distributed by the SEPAR and SEAIC to 153 members of the asthma working group from both scientific societies. For the first round of the study, a questionnaire was completed by 112 asthma specialists between October 10th and November 7th, 2023. The surveys were anonymous, and no identifiable data were collected. The questionnaire consisted of 34 items divided into several thematic sections addressing: (1) the level of awareness of the Spanish Multidisciplinary Consensus on the use of OCS in the treatment of asthma, for which participants were first asked whether they were aware of the Consensus and those who responded affirmatively were then asked to rate their degree of knowledge as low, moderate, or high, (2) opinions on the calculation, documentation, OCS dose ranges, and the duration of treatment cycles, (3) monitoring and follow-up of patients receiving OCS, and (4) opinions on biological therapy as an available alternative for patients with uncontrolled severe asthma and the management of these cases. Before beginning the questionnaire, participants were asked to indicate their specialty (allergology or pulmonology), if they practiced in a severe or uncontrolled asthma unit and if it was accredited, and whether their center had a structured referral system for patients presenting to the emergency department with asthma exacerbations.

Six months after the first questionnaire was completed, the same professionals were invited to participate, and a second round of data collection was conducted with 115 physicians, 100 of whom had participated in the first round. The questionnaire administered in this case was the same but included 4 additional questions to assess possible changes in the specialists’ perceptions compared to the first round. Furthermore, before completing the questionnaire, participants were additionally asked whether their center had a referral system from primary care for patients considered corticosteroid-dependent (according to the GEMA 5.4 guidelines).

To analyze the data, absolute and percentage frequencies were calculated for the responses to all questionnaire items in each round, for the total number of participants and by specialty. No formal statistical comparisons between rounds were conducted, as the study was designed to explore descriptive trends and the participant populations were not matched.

ResultsDemographic and clinical practice characteristics of participantsOf the 112 questionnaires completed in the first round, 55 participants were allergists, and 57 were pulmonologists; 115 participants completed the questionnaire in the second round (57 allergists and 58 pulmonologists). The prevalence of clinicians working in a severe asthma unit was high in both rounds; 75.9% (n=85) and 77.4% (n=89), respectively. Overall, 54.1% (n=46) of specialists were accredited by SEPAR, 32.9% (n=28) by SEAIC, and 12.9% (n=11) by both societies in the first round, while in the second round, these figures were 57.3% (n=51) for SEPAR, 28.1% (n=25) for SEAIC, and 9.0% (n=8) for both. A structured referral system from the emergency room to the asthma unit was reported by 46.4% (n=52) of specialists in the first round, increasing to 48.7% (n=56) in the second round. Just over one third, 37.4% (n=43), reported a structured referral system for OCS-dependent asthma patients from primary care to their asthma unit in the second round, while 62.6% (n=72) did not have such a system in place.

Knowledge and application of guidelines for OCS useThe survey results revealed that a significant majority of participants (91.1%, n=102) were familiar with the Spanish multidisciplinary consensus on the use of OCS for asthma treatment. When asked to evaluate their knowledge regarding the recommendations, 58.0% (n=65) rated their knowledge as high, while only 0.9% (n=1) rated it as very low. In terms of changes in knowledge over the past 6 months, 53.0% (n=61) reported an increase, while 46.1% (n=53) indicated that their knowledge had remained the same. With regard to the degree of agreement with the recommendations, 68.8% (n=77) reported moderate agreement, and 23.2% (n=26) stated that they agreed completely. Furthermore, 74.1% (n=83) found them quite applicable in routine clinical practice, and 14.3% (n=16) considered them totally applicable. In the second round, these figures remained stable.

No significant differences were observed between specialties in either round, apart from in the second-round's statement on knowledge of the Spanish multidisciplinary consensus, where the percentage of allergists indicating awareness increased from 87.3% (n=48) to 96.6% (n=56), thus narrowing the gap between pulmonologists and allergists.

OCS dosing, monitoring, and documentation practicesMost respondents in both rounds (70.5% and 66.1%, respectively) considered 5mg/day of prednisone equivalent to be low-dose OCS therapy, with similar trends across specialties. After this dose, 2.5mg/day was the next most selected threshold, with 18.8% (n=21) in round 1 increasing to 30.4% (n=35) in round 2, while 10mg/day was the least selected, at 0.9% (n=1). The number of respondents selecting 7.5mg/day decreased from round 1 (9.8%) to round 2 (0.9%).

A strong consensus was observed in both rounds on the classification of chronic or maintenance OCS therapy as treatment administered for 6 months or more within a year, regardless of dose, with around 97% of participants either agreeing or strongly agreeing. A similar pattern of agreement was seen for the statement defining patients with a cumulative OCS dose of 1g/year as receiving chronic or maintenance therapy, with 50.9% (n=57) and 54.8% (n=63) of respondents strongly agreeing with this statement in rounds 1 and 2, respectively.

The cumulative OCS dose per year was routinely calculated by most respondents (81.3% in round 1 and 87% in round 2), with similar frequencies across specialties, although in round 2, allergists were more likely to calculate the dose (94.7%, n=54) compared to pulmonologists (79.3%, n=46). The main reasons cited by respondents who did not calculate cumulative doses were time constraints, difficulty gathering dose information, and lack of habit (Table 1). The documentation of cumulative OCS doses in patient medical records showed some variability both within and between the rounds (Table 1). Furthermore, there appeared to be progress in the number of specialists documenting the specific OCS doses prescribed to patients by primary care (Table 1). The use of tools designed for calculating OCS doses was notably low. In round 1, only 23.2% (n=26) of clinicians reported using these tools. In round 2, this increased to 34.8% (n=40), with a preference for specific tools such as the “Nos Conecta la Salud” app (55%, n=22) and the CORTISER+ app (40%, n=16).

Selection of survey results. Those indicating a change in trend in the responses (more than a 5% difference) between the first and second rounds are shaded.

| Round 1 | Round 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Are you familiar with the Spanish multidisciplinary consensus for the use of systemic glucocorticoids for the treatment of asthma? | Yes | 91.1% | 96.5% |

| No | 8.9% | 3.5% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| How do you think your knowledge of the recommendations made in the consensus has changed in the last 6 months? | It has increased | N/A | 53.0% |

| It remains the same | N/A | 46.1% | |

| It has decreased | N/A | 0.9% | |

| Do you agree with the recommendations that have been made? | I do not agree with them | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| I agree with them a little | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Middling | 8.0% | 7.8% | |

| I agree with them quite a bit | 68.8% | 69.6% | |

| I agree with them completely | 23.2% | 22.6% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| To what extent, in general terms, do you find these recommendations easily applicable in routine clinical practice? | Not applicable | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Not very applicable | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Middling | 11.6% | 11.3% | |

| Quite applicable | 74.1% | 75.7% | |

| Totally applicable | 14.3% | 13.0% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| What dose (mg/day) of prednisone equivalent do you consider to be a low dose of OCS? | 2.5mg/day | 18.8% | 30.4% |

| 5mg/day | 70.5% | 66.1% | |

| 7mg/day | 0.0% | 1.7% | |

| 7.5mg/day | 9.8% | 0.9% | |

| 10mg/day | 0.9% | 0.9% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Why do you NOT calculate the cumulative dose? | Lack of time in the consultation due to a busy schedule | 36.4% | 6.7% |

| Lack of habit | 4.5% | 26.7% | |

| Do not usually see that patient profile | 13.6% | 0.0% | |

| Difficulty in gathering all the patient's dose information | 27.3% | 33.3% | |

| Lack of applications for calculation | 4.5% | 6.7% | |

| Have not yet implemented the consensus | 13.6% | 0.0% | |

| The patient is transferred to the severe asthma unit | 0,0% | 6.7% | |

| I only calculate it in severe asthma | 0,0% | 6.7% | |

| I make an approximate calculation | 0,0% | 13.3% | |

| Total | 100% | 100.0% | |

| Currently, in what percentage of your patients do you record the cumulative yearly dose of OCS? | More than 90% of patients | 16.1% | 20.0% |

| Between 70% and 90% patients | 11.6% | 22.6% | |

| Between 50% and 69% patients | 14.3% | 18.3% | |

| Between 30% and 49% patients | 17.9% | 13.9% | |

| Between 10% and 29% patients | 8.0% | 11.3% | |

| Less than 10% patients | 32.1% | 13.9% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Do you specifically document the doses of OCS the patient has received during emergency department visits or hospitalizations? | Yes | 58.9% | 63.5% |

| No | 41.1% | 36.5% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Do you specifically document the dose of OCS that may be prescribed to the patient by primary care? | Yes | 58.9% | 67.8% |

| No | 41.1% | 32.2% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Do you use any type of tool to facilitate the calculation of the cumulative yearly dose? | Yes | 23.2% | 34.8% |

| No | 76.8% | 65.2% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| In your opinion, what should the maximum duration of a short course of corticosteroids be? | No more than 5 days | 36.6% | 33.0% |

| No more than 7 days | 44.6% | 53.0% | |

| No more than 15 days | 17.9% | 13.0% | |

| No more than 30 days | 0.9% | 0.9% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| A patient with uncontrolled severe asthma who experiences 2 or more exacerbations requiring OCS bursts for control should be considered a candidate for biological treatment. | Totally disagree | 0.9% | 0.9% |

| Disagree | 0.9% | 0.9% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 3.6% | 5.2% | |

| Agree | 21.4% | 26.1% | |

| Totally agree | 73.2% | 67.0% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| A patient with uncontrolled severe asthma who experiences 2 or more exacerbations requiring hospitalization should be considered a candidate for biological treatment. | Totally disagree | 0.9% | 1.7% |

| Disagree | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 3.6% | 2.6% | |

| Agree | 15.2% | 14.8% | |

| Totally agree | 80.4% | 80.9% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| In order to discontinue or minimize the dose of OCS treatment, a biologic should be considered in patients with type 2 inflammation. | Totally disagree | 1.8% | 0.9% |

| Disagree | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 2.7% | 3.5% | |

| Agree | 17.9% | 26.1% | |

| Totally agree | 77.7% | 69.6% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| The use of biological treatments should be proposed in any patient with uncontrolled severe asthma receiving maintenance OCS therapy. | Totally disagree | 0.9% | 2.6% |

| Disagree | 0.9% | 0.0% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 5.4% | 1.7% | |

| Agree | 13.4% | 23.5% | |

| Totally agree | 79.5% | 72.2% | |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

When questioned on the frequency of follow-up for patients with severe asthma on maintenance OCS, most participants stated they see patients every 3 months (74.1% in round 1 and 73.9% in round 2), while only 15.2% (n=17) in round 1 and 11.3% (n=13) in round 2 reported monthly check-ups. The same 3-month interval was most common for patients receiving OCS in short courses for asthma exacerbations (supplementary material). However, a smaller percentage of clinicians monitored health parameters such as blood pressure and weight every 3 months, with 38.4% (n=43) in round 1 and 36.5% (n=42) in round 2. Monitoring of glucose levels was most commonly assessed every 6–9 months (50% and 53% of respondents in rounds 1 and 2, respectively) while more specific conditions such as bone, ocular, and gastrointestinal health were evaluated annually by 75.9% (n=85) of participants in round 1 and 72.2% (n=83) in round 2.

Perceptions of adverse events and alternative treatmentsIn round 1, 36.6% of respondents believed that the maximum duration of a short course of OCS should not exceed 5 days, while 44.6% suggested a maximum of 7 days. This perception shifted slightly in round 2, with rates of 33.0% and 53.0%, respectively, although the preference was consistent among both specialties. The percentage of respondents suggesting that a duration of 15 days could be defined as short also decreased in the second round (Table 1).

When asked if AEs related to maintenance therapy with OCS accumulate over time, 62.5% of participants in round 1 completely agreed, a rate that increased to 70.4% in round 2. In the first round, agreement varied by specialty, with 70.2% in pulmonology and 54.5% in allergology, while in round 2, these figures were 70.4% and 73.7%, respectively, evenly distributed among the specialties. The belief that a dosage exceeding 1 gram per year of OCS significantly increases the risk of AEs was shared by most clinicians: in round 1, 66.1% totally agreed and 70.4% in round 2, with a high agreement rate among specialties. A steady majority (64.3% in both rounds) completely agreed that more than 4 bursts of OCS or over 30 days of OCS treatment in a year heighten the risk of AEs. Moreover, 38.4% (n=43) fully agreed that the risk of adrenal insufficiency increases with doses exceeding 5mg/day for more than 4 weeks, and this percentage rose to 51.3% in round 2. Pulmonologists showed slightly higher agreement in both rounds compared to allergists. Consensus on the association of OCS treatment with increased healthcare costs due to AEs was prevalent, with 51.8% completely agreeing in round 1 and 58.3% in round 2.

In round 2 only, respondents were asked about the frequency of assessing severe asthma patients receiving biologics to ensure they are not receiving OCS: 56.5% reported assessing them every 3 months, and 34.8% every 6 months. A small proportion, 4.3%, reported monthly monitoring. In the case of a patient receiving a biologic requiring more than 1 short course of OCS after successful withdrawal, 48.7% of respondents stated they would consider switching the biologic if the accumulated OCS dose exceeds 0.5 grams per year. In contrast, 22.6% would consider a switch if it exceeds 1 gram yearly. The answers indicated that allergists were slightly more likely than pulmonologists to consider a switch at both thresholds. One third (33.0%) of clinicians reported taking into account the potential masking of biomarkers by prior OCS treatment when planning a biological treatment and stated that they perform clinical laboratory tests after a prudent period of time. In comparison, 63.4% stated they take it into consideration and justify it before their center's biologics committee. The figures for round 2 were similar and showed a consistent approach across specialties.

When considering a patient as a candidate for biologic treatment, a significant portion of respondents indicated that individuals with uncontrolled severe asthma who experience 2 or more exacerbations requiring bursts of OCS should be regarded as suitable for such therapy. The sentiment was similar regarding patients who experience 2 or more exacerbations requiring hospitalization (Table 1). The necessity of considering biologic treatment for patients with T2 inflammation with the intention of suspending or minimizing the OCS dose garnered significant support as well. Moreover, there was strong support for proposing biologic treatments for any patient with uncontrolled severe asthma who is on maintenance OCS (Table 1).

The complete results of both rounds of the study are provided in the supplementary material.

DiscussionThis study highlights several important findings regarding the current state of knowledge and the implementation of the Spanish consensus on the reduction of OCS use in severe asthma management.25 A substantial number of respondents reported close familiarity with the consensus recommendations, and this proportion increased over the 6 months between both study rounds. Nevertheless, challenges persist in translating this knowledge into practice. This observation mirrors the situation in other countries where similar consensus statements and strategies have been published to reduce OCS use.27 This alignment with global initiatives underlines the relevance of minimizing OCS dependency in Spain and reflects a broader international priority, highlighting the necessity of continuing efforts in this direction.24,28 In fact, our findings align with international studies indicating that the overuse of OCS and insufficient monitoring are prevalent challenges in asthma management across various regions. For instance, Dhar et al. and Maspero et al. highlighted that in Asia and Latin America, respectively, OCS are often overused in asthma management, contributing to a substantial healthcare burden.29,30 Similarly, Marques et al. emphasized the need for optimizing OCS use in severe asthma through national consensus efforts in Portugal.31 Furthermore, Bleecker et al. issued a call to action underscoring the necessity for coordinated strategies to reduce inappropriate SCS use and enhance patient safety.32

According to our results, there is room for improvement in referring patients. Rapid referral systems from emergency departments and primary care remain underutilized despite existing recommendations, while only a minority of clinicians report adequate implementation.33 Moreover, many corticosteroid-dependent patients in primary care are not referred to specialized units, which could optimize their management and taper or discontinue OCS treatment by having access to advanced therapies and phenotyping. In this context, several developed countries already have referral systems to enhance asthma management, although significant hurdles may significantly hinder their practical implementation.34 Difficulties in calculating cumulative OCS doses also emerged as a notable barrier, with limited use of available tools and a lack of integration into the electronic health record systems. The various settings in which a patient receives care may often use different electronic systems and data are not centralized, demanding extra time from professionals. Given the simplicity and practicality of these tools, it is important to promote their broader dissemination. Our findings also reveal variability when defining low-dose OCS. While GINA guidelines define a low dose as <7.5mg/day,10 most clinicians no longer adhere to this threshold, with the majority now considering <5mg/day as a low dose. Such discrepancies in defining low doses of OCS could significantly impact clinical practice and influence healthcare professionals’ perception of the associated risks, potentially leading to variations in treatment approaches and patient management strategies. This is especially relevant considering regional differences throughout Spain in the use of OCS.35 Moreover, in the second round of the study, the proportion of participants who viewed 7.5mg/day as low decreased even further, while the percentage of those who classified 2.5mg/day as low dose increased. This, coupled with the fact that most respondents agreed that an annual cumulative OCS dose exceeding 1g increases the risk of AEs, further underscores the need to minimize their use. However, the operational challenges faced by professionals in accurately tracking this information in daily practice raise the question of whether an approach based on the number of OCS bursts may be more practical than precisely calculating the cumulative dose. Moreover, a comprehensive management approach must be implemented, given that OCS administered to a patient for concurrent conditions, such as nasal polyposis, will also contribute to the overall total of OCS received. The dosage and duration of OCS cycles were highly variable among respondents. Most participants considered 5–7 days to be the ideal duration for a short course of OCS, in line with other guidelines.19,33

Numerous clinical trials and real-world registries have shown how the use of biological treatments reduces the number of patients requiring maintenance therapy with OCS and the number of exacerbations.36–40 This supports the idea that transitioning corticosteroid-dependent patients to a biologic should be considered. The switch to a biologic in cases where OCS need to be reinstated after previous discontinuation might also be an area for further in-depth research. Another consideration is that, according to our data, most clinicians assess exacerbations every 3 months, which may be a short period to evaluate treatment efficacy adequately. Given the available therapeutic options, more frequent monitoring would likely be beneficial.

An important positive aspect to highlight is the absence of significant differences in the questionnaire responses between allergists and pulmonologists, suggesting that the consensus has achieved homogeneous uptake, which is beneficial for the comprehensive care of patients. Furthermore, 75% of the participants work in accredited asthma units, and this type of organizational structure may enhance patient care by promoting a uniform framework. However, it is important to note that asthma units are not evenly distributed throughout Spain. It would therefore be worthwhile to specifically analyze the differences in how the consensus has been assimilated among these professional profiles compared to those who do not practice in such units.

While our results indicate improvements in knowledge of and agreement with the consensus recommendations, several limitations should be acknowledged. The reliance on self-reported data may introduce bias, as participants might overestimate their adherence to guidelines. While both surveys were conducted among specialists in asthma management, the populations were not completely identical in both, as they were based on voluntary responses to two independent rounds of dissemination. Therefore, comparisons are descriptive and trends should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, the generalizability of the study may be limited due to the specific demographics of the respondents, which may not reflect broader clinical practices across the country. Nonetheless, in a way, as evidenced by some response trends from round 1 to round 2, this study may have served not only to analyze the implementation of the consensus but also to reinforce clinicians’ conviction in and knowledge of these guidelines and to identify areas for future improvement.

Upcoming actions should address current limitations in implementing the consensus, particularly the need for integration of automated tools in electronic health systems, which may impact data collection on cumulative OCS doses. Efforts should also be directed toward improving referral systems to facilitate access to specialized asthma units for corticosteroid-dependent patients. Future updates to the consensus should address these barriers and promote its dissemination and application, especially in primary care and emergency settings. Further research is also needed to explore best practices for reducing OCS use and optimizing biological therapies in the management of severe asthma.

ConclusionThe results of both rounds of this study suggest significant improvements in the awareness and application of the Spanish consensus on reducing OCS use in asthma management. Nevertheless, despite increasing familiarity with these recommendations, notable challenges still need to be addressed, in particular, the optimized implementation of practices such as cumulative OCS dose calculation, structured referrals, and patient follow-up. Our findings underscore the need for continued education and system-level changes to fully integrate the consensus recommendations into routine clinical practice, as well as future actions aimed at overcoming existent barriers.

Ethical declaration statementsThe declarations regarding the approval of the research and the informed consent of the patients/participants do not apply due to the characteristics of the study, as it is a questionnaire-based study with clinicians and not involving patients.

FundingThis project was promoted and executed by the scientific societies SEPAR and SEAIC through a non-restrictive grant from AstraZeneca.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors participated in the design of the questionnaire, in the interpretation of its analysis, in the critical review, and approved the final version.

Conflicts of interestJulio Delgado has received fees as a speaker, scientific advisor, or investigator in clinical studies from AstraZeneca, BIAL, Chiesi, Faes, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva.

Xavier Muñoz Gall has received fees as a speaker, scientific advisor, or investigator in clinical studies from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Faes, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Mundifarma, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva.

Javier Domínguez-Ortega has received fees as a speaker, scientific advisor, or investigator in clinical studies from AstraZeneca, BIAL, Chiesa, GlaxoSmithKline, LETI-Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva.

Francisco Casas-Maldonado has received fees as a speaker, scientific advisor, or investigator in clinical studies from AstraZeneca, BIAL, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL-Behring, FAES, Grifols, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Novartis, Sanofi, Teva Respiratory, and VERTEX.

Marina Blanco-Aparicio has received fees as a speaker, scientific advisor, or investigator in clinical studies from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva.

Medical writing support was provided by Laura Hidalgo, PhD (Medical Science Consulting, Valencia, Spain).