To identify early predictive markers in patients with chronic interstitial pneumonia (IP) associated with an underlying autoimmune disease (AIP), aiming to facilitate personalized follow-up and treatment.

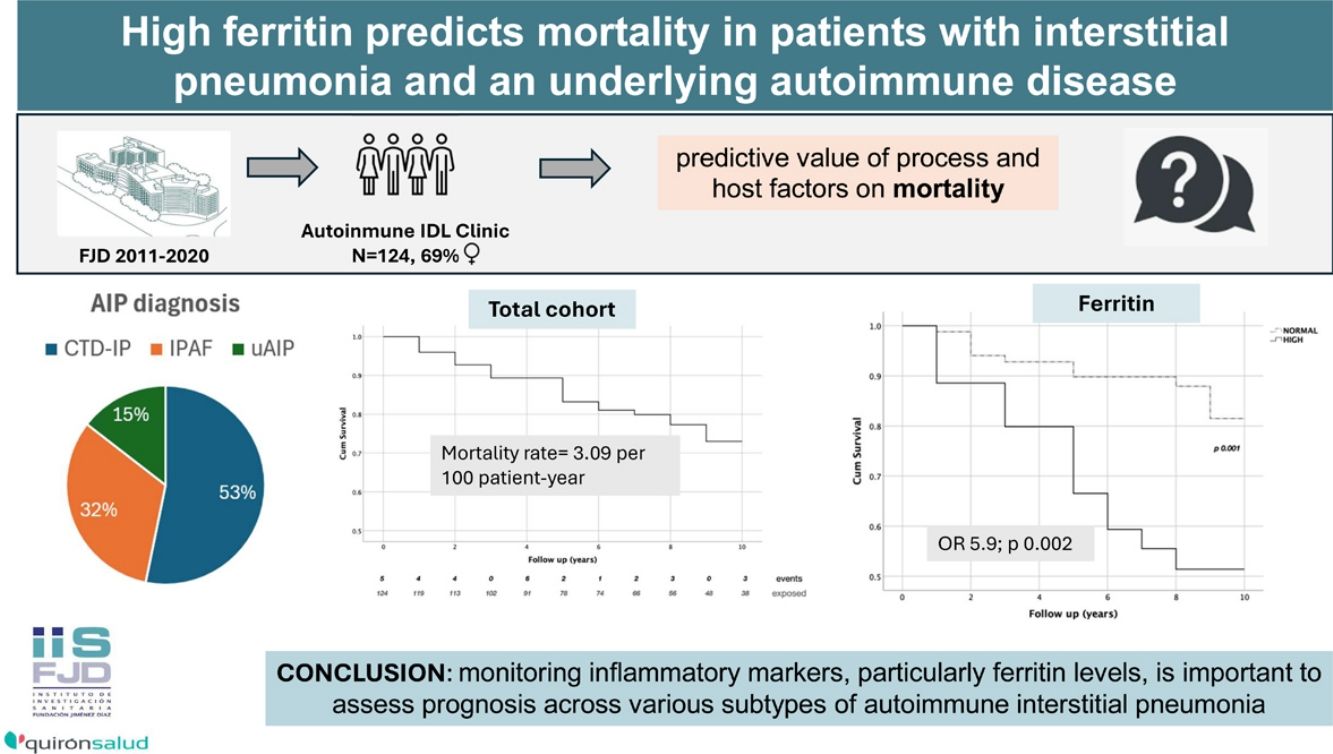

MethodsWe assessed the predictive value of process and host factors on mortality in a cohort of 124 patients (86 women) with autoimmune interstitial pneumonia (AIP). This cohort comprised 66 cases of connective tissue disease-associated interstitial pneumonia (CTD-IP), 40 patients with interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF), and 18 patients with undifferentiated autoimmune IP. All patients had a minimum follow-up of 2 years or a fatal outcome. We included demographics, clinical diagnostic subgroups, specific antibodies, morphological patterns, and relevant laboratory tests in our analysis. For the bivariate analysis, we employed Student's t-test, Fisher's exact test, and survival techniques. Prediction models for death risk were developed using logistic regression.

ResultsDuring the follow-up period, there were 29 deaths, resulting in an incidence rate of 3.09 per 100 patient-year. Factors associated with an increased risk of death included older age at diagnosis, cardio-respiratory comorbidities, and a simultaneous onset of intersticial pneumonia and systemic manifestations. In contrast, clinical diagnosis and radiographic patterns did not show a significant association with mortality risk. Additionally, elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase, sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were significantly linked to fatal outcomes. Among these, ferritin emerged as the most potent predictor in the multivariate model, with an odds ratio of 5.9 (p=0.002).

ConclusionOur data emphasize the importance of monitoring inflammatory markers, particularly ferritin levels, to assess prognosis across various subtypes of autoimmune intersticial pneumonia.

Identificar marcadores predictivos tempranos en pacientes con neumonía intersticial crónica asociada a una enfermedad autoinmune subyacente para facilitar un seguimiento y tratamiento personalizado.

MétodosEvaluamos el valor predictivo de factores de proceso y del huésped sobre la mortalidad en una cohorte de 124 pacientes (86 mujeres) con neumonía intersticial autoinmune. Esta cohorte incluía 66 casos de neumonía intersticial asociada a enfermedades del tejido conectivo, 40 pacientes con neumonía intersticial con sospecha de autoinmunidad asociada (IPAF) y 18 pacientes con neumonitis intersticial autoinmune no diferenciada. Todos los pacientes tuvieron un seguimiento mínimo de 2 años o un desenlace fatal. En nuestro análisis incluimos datos demográficos, subgrupos clínicos de diagnóstico, anticuerpos específicos, patrones radiológicos y pruebas de laboratorio relevantes. Para el análisis bivariado, empleamos Student's t-test, Fisher's exact test y técnicas de supervivencia. Los modelos de predicción de riesgo de muerte se desarrollaron mediante regresión logística.

ResultadosDurante el periodo de seguimiento hubo 29 muertes, lo que resultó en una tasa de incidencia de 3.09 por cada 100 pacientes-año. Los factores asociados con mayor riesgo de mortalidad incluyeron edad avanzada al diagnóstico, presencia de comorbilidades cardiorrespiratorias y el inicio simultáneo de manifestaciones pulmonares y sistémicas. En cambio, el diagnóstico clínico y los patrones radiográficos no mostraron una asociación significativa con el riesgo de mortalidad. Además, niveles séricos elevados de LDH, velocidad de sedimentación, proteína C reactiva y ferritina se vincularon significativamente con peor pronóstico. Entre estos, la ferritina surgió como el predictor más potente en el modelo multivariable, con una odds ratio de 5.9 (p=0.002).

ConclusiónNuestros datos resaltan la importancia de monitorizar los marcadores inflamatorios, en particular los niveles de ferritina, para evaluar el pronóstico en varios subtipos de enfermedades intersticiales pulmonares autoinmunes.

A significant proportion of patients with chronic interstitial pneumonia (IP) have an underlying autoimmune disease. While the presence of IP in these patients typically indicates a worse prognosis, the natural course of this manifestation can vary greatly.

Previously unrecognized forms of autoimmune interstitial pneumonia (AIP) have been better characterized due to advancements in clinical and laboratory tests. Notably, many patients with predominant lung involvement fall under the definition of interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF),1 a term which encompasses a group of processes of different etiopathogenesis and prognosis, making standardization of care challenging. In addition, some of the patients with a clinical suspicion of an autoimmune disease do not fulfill IPAF criteria, and there are also patients who progress through different diagnostic categories over time which encompasses a variety of phenotypes.2 Furthermore, beyond diagnostic classification, the heterogeneity of IP likely stems from both host factors and environmental exposures, which together influence immune-mediated processes. As a result, a wide range of severity can be observed not only among patients with definitive connective tissue diseases (CTD-IP) but also among those with the same clinical diagnosis.3 Given this complexity, real-world data are essential to illuminate the natural course of the different forms of AIP and to identify patients at risk of developing a progressive fibrosing phenotype.4

There has been an intensive search for biomarkers in the field of chronic fibrotic interstitial pneumonia (IP) subtypes, including various forms of connective tissue disease-associated IP (CTD-IP).5–7 In addition to markers of epithelial injury, a wide range of inflammatory mediators is currently under evaluation,8,9 some of which have been shown to predict transplant-free and decline-free survival in different subgroups of IP.10,11 The inflammatory response is recognized as a double-edged sword in the progression of interstitial lesions. On one hand, inflammation plays a crucial role in restoring homeostasis following epithelial injury; on the other hand, both recruited immune cells, and the local activation of macrophages can exacerbate airway destruction and/or promote pro-fibrotic remodeling.12

The aim of this observational study was to identify traits that could predict mortality in patients with various forms of autoimmune interstitial pneumonia (AIP). Given that autoimmune diseases are characterized by the activation of both innate and adaptive immune systems, we hypothesized that inflammatory laboratory parameters might serve as process-independent prognostic markers.

Material and methodsStudy populationThe study population comprised patients attending the Multidisciplinary Autoimmune ILD Clinic at Jimenez Diaz Foundation University Hospital between January 2011 and January 2020. Data were collected through retrospective chart review or extracted from the NEREA Registy (pNEumology RhEumatology Autoimmune disease), in which most of our patients are enrolled. The NEREA Registy was established in 2017 to record longitudinal, real-life data from patients with ILD and an underlying autoimmune disease who are under the care of Multidisciplinary Units in referral centers in Madrid.13 Variables are collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at IdISSC (Madrid) in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation.

To be included, patients needed to have a diagnosis of chronic IP according to updated ERS/ATS guidelines14 either in the context of an autoimmune disease or based on clinical suspicion of an autoimmune condition. In all cases, the final diagnosis had been confirmed by a multidisciplinary team with the participation of Radiologists, Pathologists, Rheumatologists and Pulmonologists. Only patients with a minimum follow-up of 2 years or a fatal outcome were included. Clinical diagnosis was assigned according to updated classification criteria for the CTD,15–19 and Solomon's preliminary criteria of anti-synthetase (ARS) syndrome.20 Patients not meeting the diagnostic criteria for an autoimmune disease were grouped as unclassifiable ILD, further segregating this subgroup into patients meeting Fischer's definition of IPAF1 and others considered to have an underlying “incomplete form of” connective tissue disease.

Patients were followed according to standard clinical practice. They were typically scheduled for consultations every 3–6 months once their condition was considered stable. The evaluation included blood tests and pulmonary function tests at baseline and approximately every 6–12 months. Computed tomography (CT) scans were also performed at baseline, and follow-up CT scans were requested during the follow-up period based on medical criteria.

Patients were excluded if they had a concurrent systemic illness that could interfere with the interpretation of results. Specifically, the study excluded individuals with uncontrolled lung infections, class III–IV heart failure, stages 4–5 chronic kindey disease, clinically relevant liver disease, or cognitive disorders at baseline. Additionally, patients unable to cooperate with follow-up evaluations were also excluded.

Cardio-respiratory comorbidities have been computed and considered as a whole (no/yes) while cancer was independently assessed due to its potential impact on survival or in ILD progression.

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical practice. All patients under active follow-up included in the NEREA Register have been informed and have allowed participation. Approval was granted by IIS-HU Fundación Jiménez Díaz IRB (Codes: PIC010-21_HUFJD, PIC189-21_HUFJD) and included a waiver of informed consent of historical cases.

Variables of the studyThe dependent variable in our study was death, when it was considered to be a direct consequence of pulmonary disease based on clinical chart information. Host-related factors included demographics, a history of additional cardio-respiratory comorbidities, and organ-specific autoimmune conditions. The occurrence of cancer and its timeline in relation to the presentation of interstitial pneumonia (IP) were also recorded.

Process-related variables included radiographic patterns of IP, serological markers and clinical data from early disease, which was set as the period during which diagnostic workup was conducted along with the following 12 months. The definitions of these variables are detailed in supplementary file A. The chronology of the presentation of pulmonary and associated extra-pulmonary manifestations – regardless of whether they fulfilled the criteria for a defined connective tissue disease (CTD) – was also recorded. The following laboratory parameters were assessed as risk predictors according to criteria shown in the supplementary file A: presence/absence of rheumatoid factor (RF), positive antinuclear antibodies test (ANA), positive tests for Ag-specific antinuclear antibodies, and antibodies to citrullinated peptides (ACPA); high/normal levels of immunoglobulins (Ig) IgG, IgM and IgA; increased/not increased levels of inflammatory parameters – erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP); markers associated to macrophage activation – comprising ferritin and triglycerides, and cell injury molecules – including lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and the muscle enzymes creatine phosphokinase (CK) and aldolase.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were expressed as mean (SD) and categorical variables as frequencies (%). A two-sample t-test was used for comparisons of continuous variables after assessing normality with Shapiro–Wilk test, while categorical variables were compared with Fisher's exact test. Survival techniques were used to estimate mortality rates (MR), expressed per 100 patients-year (py) with 95% confidence intervals [95% CI]. Survival curves were set to account for deaths over time. Time of observation comprised the period from IP diagnosis to the occurrence of loss of follow-up, death or end of the study. Multivariate logistic regression adjusted for confounders was done including those independent variables with a p<0.2 in the univariate analysis. Significance was set at p<0.05 in two-sided tests.

ResultsDescriptive analysisThe study population comprised 124 patients (86 women) with a mean follow-up of 7.6±4.7 years. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Study population.

| n=124 | |

|---|---|

| Women,n(%) | 86 (69) |

| Hispanic,n(%) | 15 (12) |

| Smoking status,n(%) | |

| Ever smokers | 67 (54) |

| Active smokers | 45 (36) |

| Cardio-respiratory comorbidities at onset,n(%) | 59 (48) |

| Past or present history of cancer,n(%) | 20 (16) |

| Pre-existing organ-specific autoimmune diseases | 34 (28.8) |

| Diagnostic subgroup,n(%) | |

| CTD | 66 (53) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 25 (20.2) |

| Systemic sclerosis | 16 (12.9) |

| Inflammatory myopathy | 21 (16.9) |

| Unclassifiable ILD | |

| IPAF | 40 (32.3) |

| Others | 18 (14.5) |

| Age at onset, mean (SD),median | 62.6 (14.2), 63.9 |

| Age at onset categories,n(%) | |

| ≤50 y.o. | 25 (20) |

| 51–65 y.o. | 42 (33.9) |

| 66–79 y.o. | 48 (38.7) |

| ≥80 y.o. | 9 (7.3) |

| Year of onset,n(%) | |

| Before 2008 | 28 (22.6) |

| 2008–2012 | 58 (46.8) |

| Later than 2012 | 38 (30.6) |

| Presentation,n(%) | |

| Isolated pulmonary presentation | 48 (38.7) |

| Synchronical | 31 (25) |

| Extra-pulmonary CTD features | 45 (36.3) |

| Radiographic/histological subtypes,n(%) | |

| NSIP | 43 (34.7) |

| NSIP-OP | 3 (2.4) |

| UIP | 39 (31.4) |

| Probable UIP | 14 (11.3) |

| LIP | 1 (0.8) |

| OP | 4 (3.2) |

| Non-classifiable | 20 (16.1) |

| Functional tests at disease presentation, mean (SD)median | |

| Forced vital capacity, % of predicted (FVC%) | 82.7 (23.7), 79 (n=79) |

| Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide, % of predicted (DLco%) | 65.9 (19.6), 64 (n=74) |

| Autoantibodies,n(%) | |

| Rheumatoid factor (RF) | 49 (39.5) |

| Anti citrullinated peptide (ACPA), IU/ml | 29 (23.8) |

| Anti nuclear (ANA) | 90 (73.2) |

| Myositis specific (MSA) | 29 (23.4) |

| Anti aminoacyl tRNA synthetase (ARS) | 24 (19.3) |

| systemic sclerosis specific | 8 (6.4) |

| Ro | 41 (33.3) |

Twenty-nine disease-related deaths (23.4%) occurred during the observation period. An additional eight patients died during the follow-up: four due to neoplasms (colon and lung), two due to SARS-CoV-2, one due to heart failure, and one due to end-stage renal failure. The prevalence of events in relationship with host and disease factors is shown in Table 2. In detail, fatal cases were older at onset (difference: 11.8±2.8 yr, p<0.001). Similarly, an association was found for increasing age categories. Women showed a higher proportion of deaths as compared to men (26.7% vs. 15.8%) albeit not reaching significance. As refers to other sociodemographic factors, patients with cardio-pulmonary comorbidities had a 30.5% of events as compared to 15.6% in those subjects without (p 0.048), while smoking status did not yielded significant differences in death prevalence.

Death prevalence.

| Gender | ||

| Women | 23/86 (26.7%) | p 0.251 |

| Men | 6/38 (15.8%) | |

| Age category at onset | ||

| ≤50 y.o. | 1/25 (4%) | p 0.002 |

| 51–65 y.o. | 7/42 (17%) | |

| 66–79 y.o. | 16/48 (33.3%) | |

| ≥80 y.o. | 5/9 (55.6%) | |

| Age at onset | ||

| Alive | 59.8±1.4 [56.9, 62.7] | diff: −11.8±2.8 [−17.4, −6.2], p<0.001 |

| Dead | 71.6±1.9 [67.8, 75.5] | |

| Cardio-respiratory comorbidities at onset | ||

| Absence | 10/64 (15.6%) | p 0.056 |

| Presence | 18/59 (30.5%) | |

| History of cancer | ||

| Negative | 22/104 (21.1%) | p 0.246 |

| Positive | 7/20 (35%) | |

| Pre-existing organ-specific autoimmune diseases | ||

| Absence | 23/84 (27.4%) | p 0.347 |

| Presence | 6/34 (20.7%) | |

| Smoking | ||

| Never | 16/57 (28.1%) | p 0.305 |

| Past | 6/22 (27.3%) | |

| Active | 7/45 (15.6%) | |

| Year of onset | ||

| Before 2008 | 28 (22.6) | p 0.678 |

| 2008–2012 | 58 (46.8) | |

| Later than 2012 | 38 (30.6) | |

| Presentation | ||

| Synchronical | 9/31 (29%) | p 0.463 |

| Non synchronical | 20/93 (21.5%) | |

| Clinical diagnosis (vs. others) | ||

| RA | 7/25 (28%) | p 0.599 |

| SSc | 2/16 (12.5%) | p 0.353 |

| IM | 5/21 (23.8%) | p 1.0 |

| Unclassifiable ILD | ||

| IPAF | 10/40 (25%) | p 0.822 |

| Others | 5/18 (27.8%) | p 0.763 |

| ARS criteria | 3/21 (14.3%) | p 0.399 |

| Radiographic pattern (vs. others) | ||

| UIP pattern | 14/53 (26.4%) | p 0.525 |

| NSIP pattern | 10/46 (21.7%) | p 0.828 |

| FVC% of predicted, mean±SD [95% CI] | ||

| Alive | 84.0±24.7 [77.9, 90.0] | p 0.239 |

| Dead | 76.2±17.4 [65.7, 86.7] | |

| DLco, % of predicted, mean±SD [95% CI] | ||

| Alive | 66.3±19.6% [61.3, 71.2] | p 0.837 |

| Dead | 64.0±20.1% [50.5, 77.5] | |

| Autoantibodies (vs. absence) | ||

| ANA | 19/90 (21.1%) | p 0.339 |

| Positive RF | 11/49 (22.4%) | p 1.000 |

| Presence of ACPA | 7/29 (24.1%) | p 1.000 |

| Myositis specific autoantibodies | 6/28 (21.4%) | p 0.806 |

| Positive Ro antibodies | 6/14 (14.6%) | p 0.120 |

| Presence of Ro 52kDa antibodies | 1/20 (5%) | p 0.07 |

| Altered laboratory parameters (vs. normal) | ||

| ESR | 23/72 (31.9%) | p 0.01 |

| CRP | 26/80 (32.5%) | p 0.001 |

| Ferritin | 15/36 (41.7%) | p 0.004 |

| Triglycerids | 7/13 (53.8%) | p 0.014 |

| LDH | 20/59 (33.9%) | p 0.011 |

Considering types of presentation, we found 29% of fatal events during follow-up in patients with synchronical pulmonary and extra-pulmonary disease, while the prevalence was 21.5% in the other patients (ns). At the time of disease onset, functional tests were not available in 70 of the patients (20 of whom had a fatal outcome). Thus, even though the survivors had higher FVC than the deceased the difference was not significant. Determination of DLco did not show differences between survivors and deceased. On the other hand, there were no significant differences between diagnostic subgroups, and neither were there between UIP and NSIP radiographic patterns.

Similarly, subgrouping the sample by type of autoantibodies did not yield relevant differences in death prevalence, which was 21% in ANA+ cases, 22% in patients with RF and 27% in those with MSA. However, there was an exception: the prevalence of death was slightly lower in patients with Ro antibodies (15%, p=0.095) compared to those without. In particular, the prevalence was markedly reduced in carriers of Ro 52kDa antibodies (5%, p=0.022).

We further focused on the prognostic role of laboratory parameters of the systemic condition. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was raised in 58% (72 p), while CRP was elevated in 64% of the subjects (80 p). Twenty-nine % (36 p) of the patients showed increased ferritin levels and 11% (13 p) had high triglycerides. Abnormally increased CK and/or aldolase were observed in 12% and 15% of the patients tested, respectively, whereas lactate dehydrogenase was elevated in 48% of the patients. Levels of IgG, IgA and IgM were found increased in 12% (14 p), 26% (29 p), and 2%, respectively.

Interestingly, increases of ESR, CRP, ferritin and LDH were associated to significantly higher death frequencies, rising to 31.9% (p 0.006), 32.5% (p 0.001), 41.7% (p 0.003) and 33.9% (p 0.008), respectively. None of the other laboratory parameters showed a relationship with fatal events.

Table 3 lists the diagnoses and indicates their association with death and increased/normal ferritin levels. Table 4 presents the average values of C-reactive protein, ferritin, and LDH.

Diagnoses and association with death and increased/normal ferritin levels.

| Diagnosis | Death | Ferritin(n=120) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase | Normal | |||

| RA (n=23) | No | 4 | 12 | 16 |

| Yes | 3 | 4 | 7 | |

| DM (n=4) | No | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| AD (n=6) | No | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| MCTD (n=1) | No | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| SSc (n=13) | No | 0 | 12 | 12 |

| Yes | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| IPAF+unclassifiable ILD (n=57) | No | 10 | 32 | 42 |

| Yes | 7 | 8 | 15 | |

| Overlap RA-Sjögren (n=1) | No | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Overlap SSc-SLE (n=1) | No | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Overlap SSc-IM (n=1) | No | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| IM (n=9) | No | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sjögren (n=4) | No | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total (n=120) | No | 20 | 70 | 90 |

| Yes | 15 | 15 | 30 | |

RA: rheumatoid arthritis; DM: dermatomyositis; AD: amyopathic dermatomyositis; MCTD: mixed connective tissue disease; SSc: systemic sclerosis; IPAF: interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features; IM: inflammatory myositis; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus.

With a total follow-up of 937.13 py, the MR from the cohort was 3.09 per 100 py [95% CI: 2.15, 4.45]. The probability of survival was 81±4% at 5 years and 73±5% at 8 years from disease onset (Fig. 1).

As shown in Table 5, higher MR were found in relationship with increasing age, cardio-respiratory comorbidites (MR: 4.47) and in women (MR: 3.45). An effect related to calendar time was observed, with patients diagnosed before 2008 exhibiting lower mortality compared to those diagnosed more recently. The latter group also had a shorter cumulative follow-up. Active smokers had also higher MR (5.05). With regards to process-related factors, patients diagnosed with RA and those with uAIP had higher MR, while comparatively SSc patients showed the highest survival (MR: 1.45). Patients presenting with synchronical pulmonary and extra-pulmonary symptoms showed a MR of 4.53. The UIP radiographic pattern was associated to a 3.52 MR, while patients with an NSIP showed 2.97.

Mortality rates in subgroups of patients.

| Exposure (py) | Events | Rate [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Women | 666.63 | 23 | 3.45 [2.29, 5.19] |

| Men | 270.5 | 6 | 2.22 [0.99, 4.94] |

| Age category at onset | |||

| <50 y.o. (ref.) | 227 | 1 | 0.44 [0.06, 3.13] |

| 51–65 y.o. | 311.1 | 7 | 2.25 [1.07, 4.72] |

| 66–79 y.o. | 336.8 | 16 | 4.75 [2.91, 7.75] |

| >79 y.o. | 38.21 | 5 | 13.1 [5.5, 31.4] |

| Cardio-respiratory comorbidities | |||

| No | 526.5 | 10 | 1.90 [1.02, 3.53] |

| Yes | 403 | 18 | 4.47 [2.81, 7.09] |

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 451.9 | 16 | 3.54 [2.17, 5.78] |

| Ex or current | 451.3 | 13 | 2.88 [1.67, 4.96] |

| Current | 118.9 | 6 | 5.05 [2.26, 11.23] |

| Year of onset | |||

| Before 2008 | 377.2 | 7 | 1.86 [0.88, 3.89] |

| Between 2008 and 2012 | 417.0 | 15 | 3.6 [2.17, 6.0] |

| Later than 2012 | 143.0 | 7 | 4.9 [2.33, 10.27] |

| Presentation | |||

| Pulmonary dominant | 384.2 | 10 | 2.60 [1.40, 4.84] |

| Autoimmune disease | 354.3 | 10 | 2.82 [1.52, 5.24] |

| Synchronical | 198.6 | 9 | 4.53 [2.36, 8.71] |

| Clinical diagnosis | |||

| RA | 168.8 | 7 | 4.15 [1.98, 8.70] |

| SSc | 138.0 | 2 | 1.45 [0.36, 5.79] |

| IM | 146.3 | 5 | 1.62 [0.61, 4.31] |

| IPAF | 303.8 | 10 | 3.29 [1.77, 6.12] |

| uAIP | 124.9 | 5 | 4.00 [1.67, 9.61] |

| ARS criteria | 169.6 | 3 | 1.77 [0.57, 5.48] |

| Radiographic pattern | |||

| UIP pattern | 397.1 | 14 | 3.52 [2.09, 5.95] |

| NSIP pattern | 336.4 | 10 | 2.97 [1.60, 5.52] |

| Autoantibodies | |||

| Positive ANA | 709.7 | 19 | 2.68 [1.71, 4.20] |

| Positive RF | 339.0 | 11 | 3.25 [1.80, 5.86] |

| Presence of ACPA | 214.2 | 7 | 3.27 [1.56, 6.85] |

| Presence of MSA | 203.3 | 6 | 2.95 [1.33, 6.57] |

| Positive Ro antibodies | 316.2 | 6 | 1.90 [0.85, 4.22] |

| Presence of Ro 52kDa antibodies | 161.7 | 1 | 0.62 [0.09, 4.39] |

| ESR | |||

| Low | 437.7 | 6 | 1.37 [0.62, 3.05] |

| High | 499.4 | 23 | 4.60 [3.06, 6.93] |

| CRP | |||

| Low | 409.5 | 3 | 0.73 [0.24, 2.27] |

| High | 527.7 | 26 | 4.93 [3.35, 7.24] |

| Ferritin | |||

| Low | 711.9 | 14 | 1.97 [1.16, 3.32] |

| High | 223.1 | 15 | 6.72 [4.05, 11.15] |

| LDH | |||

| Low | 550.7 | 9 | 1.63 [0.85, 2.14] |

| High | 386.4 | 20 | 5.18 [3.34, 8.02] |

Survival techniques were employed to assess differences between subgroups over time, disclosing a lack of effect of the diagnostic conditions (not shown) and the radiographic patterns in the incidence of death over a 10-year period (Fig. 2).

Regarding serological markers, the presence of Ro 52kDa antibodies was associated with lower mortality (mortality ratio: 0.62). Finally, high levels of ESR, CRP, ferritin or LDH resulted in an increase in MR, reaching 6.72 in patients with high ferritin and 4.93 in those with high CRP. Fig. 3 shows the marked differences in survival curves attending to these laboratory markers.

Multivariate analysis of death riskA multivariate analysis using logistic regression was built with the independent factors which yielded the strongest associations in the bivariate analysis. Gender and smoking were included in the assessment but dropped from the model with p values >0.8. A 4-factor model – adjusted for calendar time and for the presence of an UIP radiographic pattern – which included age, presence of cardio-respiratory comorbidities, a synchronical disease presentation and increased ferritin at disease onset was found to be the best death predictor (Table 6). The most powerful predictive factors in the model were age, which conferred a 1.12-fold increased risk per year (p<0.001), and ferritin, with an OR of 5.96 (p 0.002).

Multivariate regression model of death risk.

| Factor | OR mean±SEM [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.18±0.03 [1.06, 1.18] | p<0.001 |

| Calendar time | 0.41±0.16 [0.19, 0.89] | p 0.024 |

| UIP pattern | 0.72±0.38 [0.25, 2.04] | p 0.535 |

| Cardio-respiratory comorbidities | 2.91±1.60 [0.99, 8.57] | p 0.052 |

| Synchronical presentation | 2.76±1.64 [0.86, 8.85] | p 0.088 |

| Ferritin | 0.17±0.10 [0.06, 0.54] | p 0.002 |

| Global test | p<0.001 |

This real-life cohort study offers an overview of prognostic factors across various interstitial pneumonia (IP) syndromes with an autoimmune background. Our results indicate that clinical diagnosis and radiographic patterns have minimal impact on predicting outcomes at the time of disease presentation, while highlighting the significance of inflammatory parameters.

We observed a significantly higher survival rate in our patients compared to various interstitial pneumonia (IP) cohort studies, likely due to the higher proportion of connective tissue disease-associated IP (CTD-IP) cases in our study population, as well as a younger age and a predominance of women.21–24 Notably, our patients with interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) had survival rates comparable to those with definite connective tissue disease (CTD), while the increased number of events in others unclassifiable autoimmune interstitial pneumonia appeared to be related to their older age at disease onset. Our findings align with a cohort study of 456 cases, which reported no significant differences in transplant-free survival among diagnostic subgroups.25

The recognition of significant discrepancies in outcomes among patients with the same diagnosis highlights the need to transition from clinical diagnosis to more homogeneous phenotypes, as defined by a range of host and process-related factors.3,26 Between these factors, the gender-age-physiology (GAP) scoring accounts for a predictive tool of functional deterioration and survival across different diagnostic subgroups, including CTD-IP forms.27–30 Although we were unable to use the GAP index due to the characteristics of our study, we confirmed the impact of older age and cardio-respiratory comorbidities on mortality rates. This finding aligns with recent data suggesting that combining chronic comorbidities with GAP scoring enhances death prediction models.31 The strongest predictor of death in our cohort was age at desease presentation. This fact has also been observed in other ILD cohorts, including the one from Feltrer-Martínez et al.32

On the other hand, the predominance of women in our cohort may have masked the presumed effect of male gender on mortality. In this context, various research groups advocate for the classification of interstitial pneumonia (IP) patients using cluster analysis, which has proven to be more effective in predicting outcomes than traditional disease classifications, initial IP types, or GAP scores. As an illustration, a cohort study from Chicago identified a cluster that closely resembles our study population – consisting of younger patients, a higher proportion of women, and an autoimmune background – which demonstrated better survival probability.33 Interestingly, this approach revealed that the usual UIP radiographic pattern was evenly distributed among prognostic clusters,34 thereby challenging the assumed negative impact of this pattern on survival.

A notable finding from our study was the poorer outcomes in patients exhibiting simultaneous pulmonary and extra-pulmonary features, suggesting that this disease type may require closer surveillance. One possible explanation is that this category likely includes rapidly progressive forms of interstitial pneumonia (IP), which are associated with higher short- and mid-term mortality.

Finally, molecular biomarkers present promising candidates for predicting outcomes. Given the significance of autoantibodies in differentiating autoimmune interstitial pneumonia (AIP) subgroups, several studies have investigated their potential as predictive biomarkers.35 However, the presence of ANA lacks enough specificity by itself while the low prevalence of the more specific autoantibodies complicates their assessment. In this context, our results suggest that carriers of anti-Ro 52kDa antibodies may have a higher probability of survival, supporting previous findings from our group that indicated a “protective” effect of Ro antibodies in patients with interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) exhibiting a UIP pattern.36 Nonetheless, the relevance of this association needs to be replicated in larger cohorts.

Various mediators involved in cell recruitment, neutrophil activation, endothelial dysfunction, and immune dysregulation drive the search for laboratory biomarkers of interstitial pneumonia (IP). Additionally, inflammation is believed to contribute to deterioration across different subtypes of progressive fibrotic IP.10,37 In patients with both idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial pneumonia (SSc-IP), elevated levels of IL-6, which orchestrates the acute phase response, have been associated with disease severity and progression.38 Our results indicate that erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, as surrogate markers of the acute phase response, could serve as valuable tools for quickly assessing severity in patients with autoimmune interstitial pneumonia (AIP). Indeed, elevated CRP levels have been associated with poor prognosis in certain forms of interstitial pneumonia (IP), including systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial pneumonia (SSc-IP), idiopathic inflammatory myopathy-associated interstitial pneumonia (IIM-IP), and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), particularly in the context of acute exacerbations.34 Among all laboratory parameters, however, ferritin demonstrated the strongest association with fatal outcomes. Hyperferritinemia is commonly associated with certain forms of inflammatory myopathies, including ARS and MDA5-positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis, where it has consistently been linked to rapid disease progression and increased mortality.39–41 Serum ferritin >2200ng/ml predicted patient's death within half a year in MDA5+ patients with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease, but not in anti-synthetase syndrome.42

Our results, with low ferritin levels (mean 186ng/ml±310 SD), support the role of ferritin as a marker of disease severity across various phenotypes, not only in the short term but also in chronic IP.

Elevated plasma ferritin levels indicate a particularly severe inflammatory response characterized by persistent activation of macrophages with a predominant M2 polarization.43 These cells, which typically display an immunosuppressive phenotype, also promote fibrotic remodeling following injury.44 Collectively, this suggests that macrophages may act as key drivers of the fibrotic process in severe forms of AIP.

The assumption in the analysis that a biomarker measured at baseline can predict mortality almost 7 years later is understood. Most biomarkers are dynamic and change during follow-up (lung function, radiology, serum biomarkers), influenced by disease and treatments. Therefore, it will be attempted to reduce this bias by analyzing our data in a shorter period. The analysis of 84 patients with available functional follow-up, showed no correlation between a 10% decline in FVC and the average ferritin levels in the first two years (p=0.214) or CRP (p=0.206), but did show a correlation with average LDH levels (p=0.014).

Our study has several important limitations. Due to the varying timeframes of diagnosis among patients, we were unable to compare functional tests at baseline. The decision to categorize laboratory parameters into “normal” and “increased,” while intended to mitigate biases related to various factors, inherently resulted in a loss of granular information regarding the extent of change within these categories. For instance, a marginal increase and a substantial elevation in a given analyte were both classified as “increased,” potentially obscuring subtle but clinically relevant differences in their association with disease progression or treatment response. Additionally, we could not assess many factors that may impact survival, such as exacerbations and diagnostic delays. Furthermore, we did not examine the effects of interventions that could influence disease progression and improve outcomes. On the other hand, certain research questions can be more effectively addressed through real-life studies. In this context, our study spans a long duration, encompasses a wide range of phenotypes, and is grounded in a detailed characterization of the disease resulting from multidisciplinary practice.

In summary, our results support the measurement of acute phase response markers and ferritin levels, alongside disease-related factors, to gain a clearer understanding of disease severity in patients with IP and underlying autoimmune disease.

Informed consentThe authors confirm that the patient's written consent has been obtained.

Authors’ contributionsMJRN: Conceptualisation, curation of data, interpretation of results, manuscript review. FRB: Conceptualisation, data collection, methodology, interpretation of results, manuscript review. LA: Formal analysis, methodology, manuscript review. MCVS: Data collection, manuscript review. CPM: Methodology, data collection, manuscript review. OSP: Conceptualisation, formal analysis, methodology, interpretation of results, manuscript writing, corresponding author.

FundingThe authors declare that no external funding was used for the development of this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in relationship with the work submitted for publication.