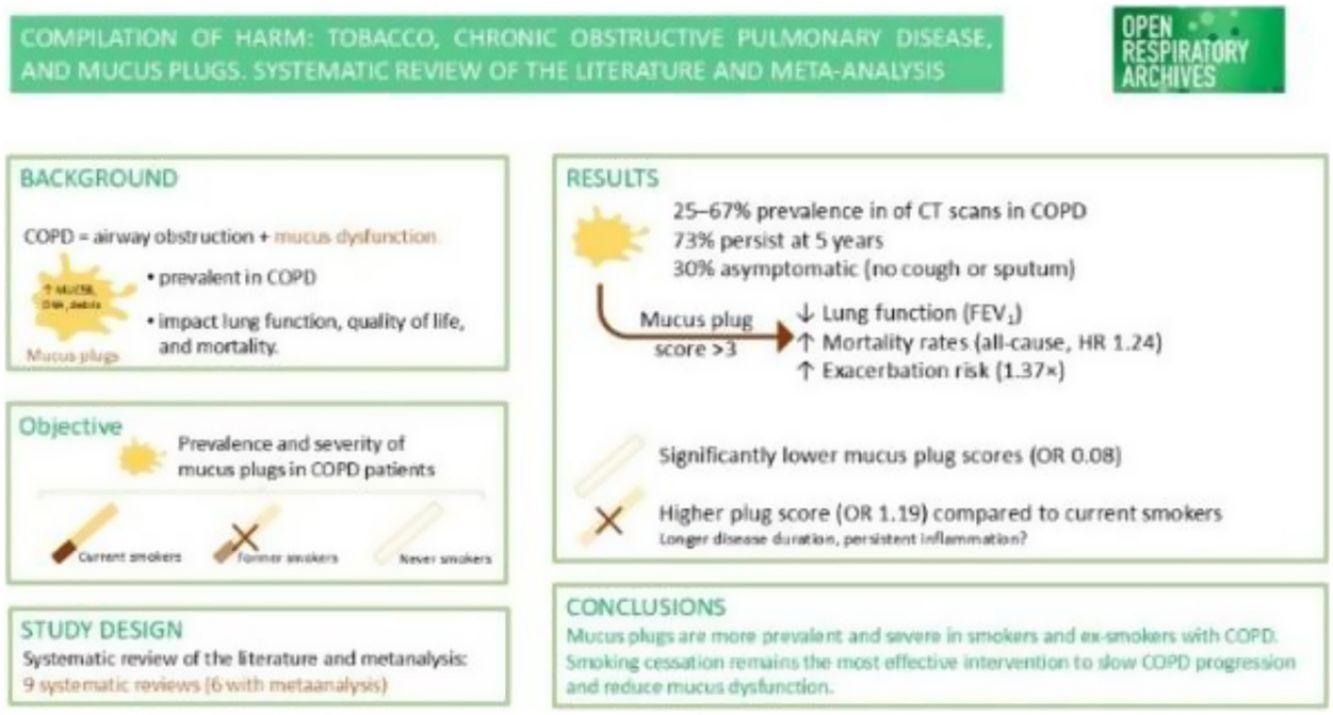

In COPD patients, mucus plugs are associated with lower lung function, worse quality of life, higher all-cause mortality, and a higher rate of exacerbations. The aim of the study was to determine whether subjects with COPD with a higher cumulative smoking history, such as current smokers, have a higher mucus plug score compared to former and never smokers with COPD.

Material and methodsWe have carried out a systematic review of the literature (SRL) and a meta-analysis (MA).

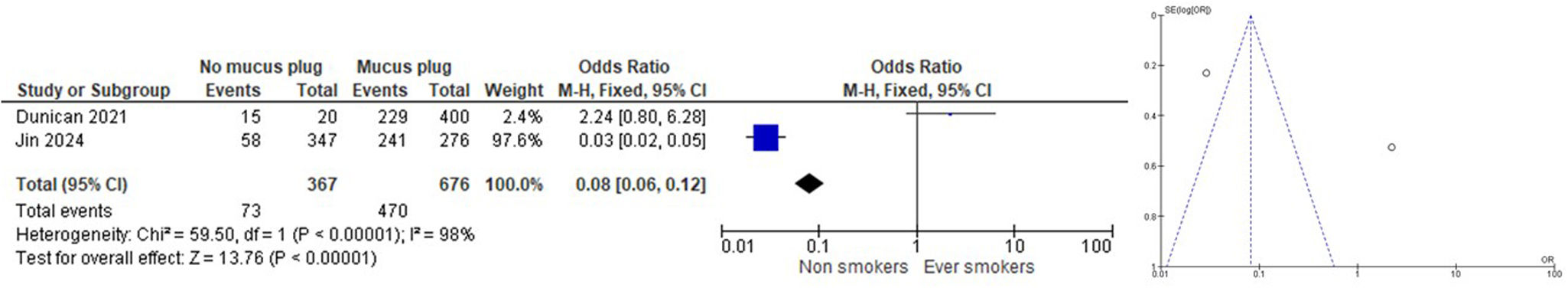

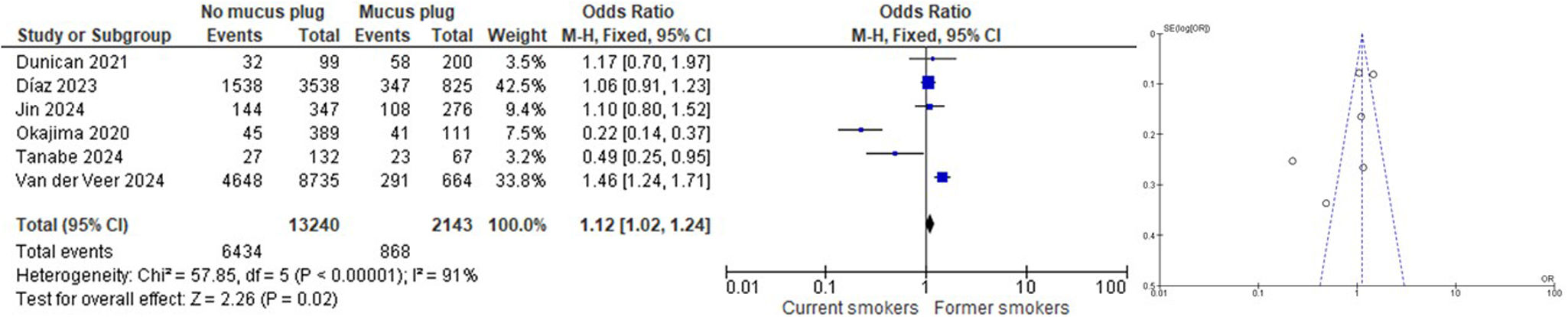

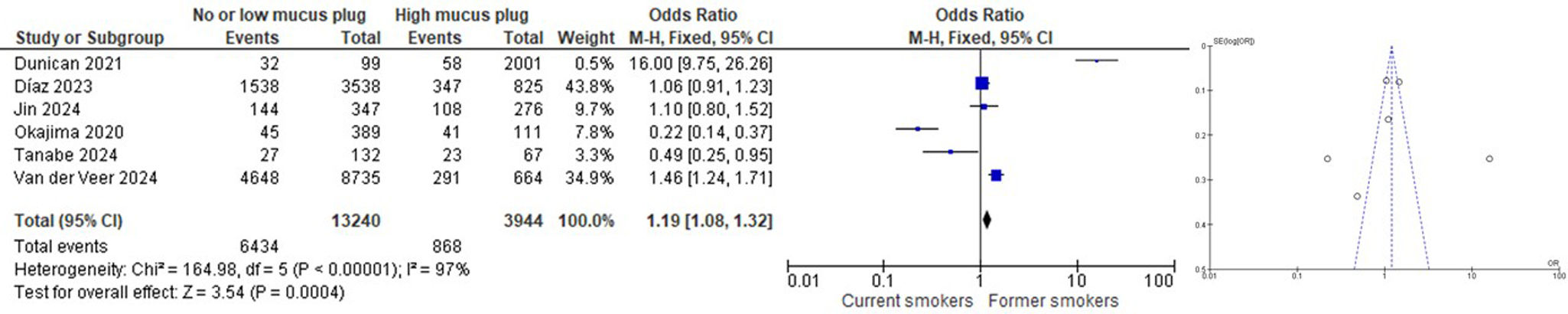

ResultsNine articles were finally included in the SRL, and 6 of them were part of the MA. We found that subjects who had never smoked had a lower rate of mucus plugs when compared to active and ex-smokers (OR 0.08 [CI 95% 0.06, 0.12]). When comparing subjects with and without mucus plugs between current smokers vs. ex-smokers, we found that ex-smokers had a higher rate of mucus plugs than current smokers (OR 1.12 [CI 95% 1.02, 1.24]). When comparing subjects without mucus plugs or with a low mucus plug score (0–2) with a high mucus plug score (>3) between current smokers vs. ex-smokers, we found that ex-smokers had a higher mucus plug score than current smokers (OR 1.19 [CI 95% 1.08, 1.32]).

ConclusionsWe found that subjects who have never smoked have a lower rate of mucus plugs than those who have smoked and that ex-smokers with COPD have a higher rate of mucus plugs than current smokers with COPD. Quitting smoking is the most significant modifiable risk factor for COPD.

En pacientes con EPOC, los tapones mucosos se asocian con una función pulmonar más baja, peor calidad de vida, mayor mortalidad por cualquier causa y una mayor tasa de exacerbaciones. El objetivo del estudio fue determinar si los sujetos con EPOC con un mayor historial de tabaquismo acumulado, como los fumadores actuales, presentan una mayor puntuación de tapón mucoso en comparación con los exfumadores y los nunca fumadores con EPOC.

Material y métodosSe realizó una revisión sistemática de la literatura (SRL) y un metaanálisis (MA).

ResultadosNueve artículos se incluyeron finalmente en la SRL, y 6 de ellos formaron parte del MA. Se observó que los sujetos que nunca habían fumado presentaron una menor tasa de tapones mucosos en comparación con los fumadores activos y exfumadores (OR: 0,08 [IC 95%: 0,06-0,12]). Al comparar sujetos con y sin tapones mucosos entre fumadores actuales y exfumadores, se observó que los exfumadores presentaron una mayor tasa de tapones mucosos que los fumadores actuales (OR: 1,12 [IC 95%: 1,02-1,24]). Al comparar sujetos sin tapones mucosos o con una puntuación baja de tapón mucoso (0-2) con una puntuación alta de tapón mucoso (>3) entre fumadores actuales y exfumadores, se observó que los exfumadores presentaron una puntuación de tapón mucoso mayor que los fumadores actuales (OR: 1,19 [IC 95%: 1,08-1,32]).

ConclusionesSe observó que los sujetos que nunca han fumado presentan una menor tasa de tapones mucosos que los que han fumado, y que los exfumadores con EPOC presentan una mayor tasa de tapones mucosos que los fumadores actuales con EPOC. Dejar de fumar es el factor de riesgo modificable más significativo para la EPOC.

Airway mucus represents a multi-component secretion best described as a biological hydrogel composed of water, ions, proteins, lipids, polymerizing mucin glycoproteins (MUC5B and MUC5AC), a range of antimicrobial molecules (defensins, lysozyme, etc.), cellular components (cellular debris including DNA and keratin), and protective factors (trefoil factors). All such components are perpetually synthesized, secreted, and integrated into mucus before appropriate degradation and clearance.1,2

Pathologic processes that result in blockage and flow stagnation within the tracheobronchial tree can change the composition of mucus. Mucus that is abnormally thick in consistency and plugs the airway is known as a mucus plug.3 Mucus plugs can block one or more airways entirely or partially, which can have major repercussions, such as atelectasis and repeated infections. Additionally, impacted mucus can result in a bronchial cast, a semisolid blockage inside a bronchus that assumes the shape of the airway within which it formed.3 In some airway diseases, mucus plugs visible on imaging and bronchoscopy can serve as diagnostic indicators. Patients with chronic airway diseases, such as asthma, cystic fibrosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), have increased baseline levels of mucin, and acute exacerbations of disease further contribute to this effect.2,3

COPD is a heterogeneous lung condition characterized by chronic respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, cough, sputum production, and/or exacerbations) due to abnormalities of the airways (bronchitis, bronchiolitis) and/or alveoli (emphysema) that causes persistent, often progressive, airflow obstruction.4 Chronic bronchitis is defined by the presence of cough with expectorated sputum on a regular basis over a defined period (chronic cough and sputum production for at least 3 months per year for two consecutive years, in the absence of other conditions). Using this definition, the prevalence of chronic bronchitis ranges from 25% to 35% in COPD, including male sex, younger age, greater pack-years of smoking, more severe airflow obstruction, rural location, and increased occupational exposures, but the primary risk for chronic bronchitis is smoking.4

In chronic bronchitis, COPD patients MUC5B levels markedly increase due to submucosal gland hyperplasia, and airway occlusion can occur. In disease states, thick and viscoid mucus can lead to airway inflammation and infection. The two main signs of impaired mucous clearance are cough and dyspnea. Cough and sputum production are primarily linked to mucus production in the large airways, but luminal occlusion is also linked to mucus production in the smaller airways.4 Radiographic manifestations of mucous plugging may be present and persist in patients with COPD despite a lack of chronic bronchitis symptoms and are associated with greater airflow obstruction, lower oxygen saturation, worsened quality of life, and all-cause mortality.4 Emphysema and small airway remodeling/loss are well-known pathological features of COPD. However, studies of excised lung tissue also show that luminal occlusion by mucus exudates are critical pathologic features.5 The relationship between chronic mucus production and lung function, exacerbation, and mortality has been fully investigated.6–16

So, the presence of mucus plugs on computed tomography (CT) is associated with lower lung function, worse quality of life, higher all-cause mortality, and COPD pathogenesis, progression, and exacerbations. A scoring system was used to classify mucus plugs.17,18

It is known, without a doubt, that smoking is a cause of COPD and not only active smoking. Cigarette smoking is a key environmental risk factor for COPD. Cigarette smokers have a higher prevalence of respiratory symptoms and lung function abnormalities, a greater annual rate of decline in FEV1, and a greater COPD mortality rate than non-smokers.4 Not only is active smoking associated with COPD, but also second-hand smoking may also contribute to respiratory symptoms and COPD, especially after long-term exposure.19–21

We hypothesized that in patients with COPD, both those with a higher cumulative smoking history and current smokers have higher mucus plug scores compared with former and never smokers with COPD. So, we have carried out a systematic review of the literature (SRL) and a meta-analysis (MA) of different works with the aim of answering the following question of interest: Do those with COPD with a higher cumulative smoking history, such as current smokers, have a higher mucus plug score compared to former and never smokers with COPD?

To concentrate the search for available evidence, the clinical question was transformed into the PICO format: patient (problem or population), intervention, comparison, and outcome (relevant outcome).22

Material and methodsSelection criteriaThe SRL was carried out on January 15th, 2025, in the Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Embase databases without using language and time restrictions. Documents identified in the articles collected in the search strategy were also added. The protocol has been registered at PROSPERO (CRD42025638104).

Search strategyAs a search strategy, we used the following search terms used with their corresponding truncations depending on the database used and the use of quotation marks (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease*”, and copd; mucus plug: “mucus plug*”, “mucous plug*”, “plug* mucous*”, “plug* mucus”, mucus near/3 plug* and mucous near/3 plug*) in the article title, abstract, and keywords (descriptors), depending on the possibilities offered by each of the databases, including papers and review articles as documentary typologies. Differences and search characteristics according to database:

- -

PubMed: This database was searched by title, abstract and MeSH because it does not have the option to search by author keywords. In this database the search strategy was: (“mucus plug*”[Title/Abstract] AND “copd”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“mucus plug*”[Title/Abstract] AND “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease*”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“mucous plug*”[Title/Abstract] AND “copd”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“mucous plug*”[Title/Abstract] AND “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease*”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“mucus plug*”[Title/Abstract] AND “pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive”[MeSH Terms] “) OR (”mucous plug*“[Title/Abstract] AND” pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive“[MeSH Terms]”). Total records recovered: 83.

- -

Web of Science (Core Collection): In this database, the search was performed by topic (title, abstract and keywords). The search strategy was: TS=(“chronic obstructive pulmonary disease*” or copd) AND TS=(“mucus plug*” or “mucous plug*” or “plug* mucous*” or “plug* mucus” or mucus near/3 plug* or mucous near/3 plug*). Total records recovered: 81.

- -

Scopus: The search in Scopus was performed on the title, abstract and keywords. The search strategy was: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“chron* obstruct* pulmon* disease*” OR copd) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“mucus plug*” OR “mucous plug*” OR or “plug* mucus” OR “plug* mucous*”). Total records recovered: 90.

- -

Embase: This database was searched without field limitations, as there is a field called Disease Terms that includes the expression chronic obstructive pulmonary disease combined with the expression mucus plug that appears in the title, abstract, or keywords. The search strategy was: (‘chron* obstruc* pulmon* disease*’ OR ‘copd’/exp OR copd) AND (‘mucus plug*’ OR ‘mucous plug*’ OR ‘plug* mucus*’ OR ‘plug* mucous*’). Total records recovered: 126.

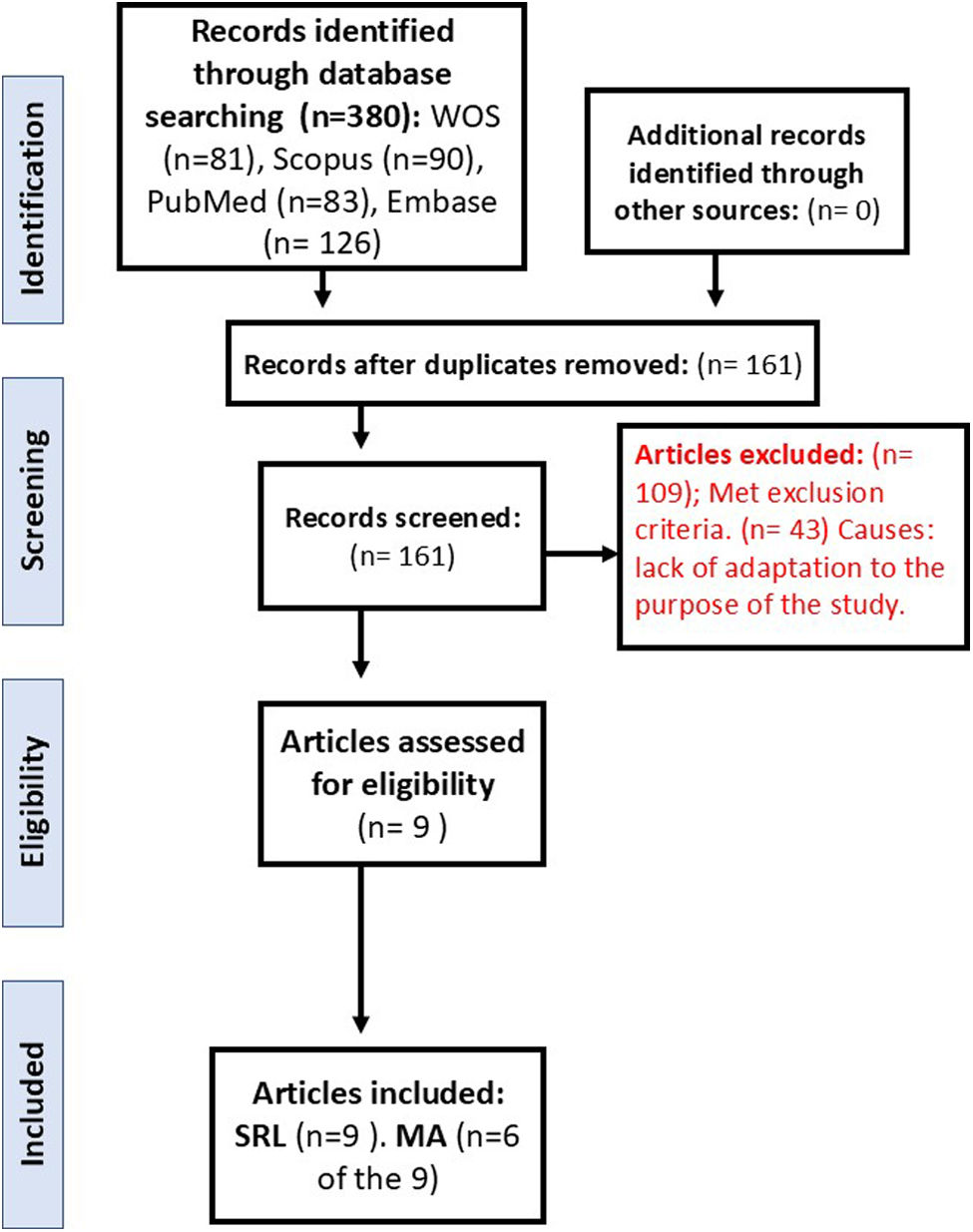

The SRL protocol was designed following the principles of the Cochrane Collaboration (https://community.cochrane.org/organizational-info/resources/policies/policies-all-members-and-supporters/principles-collaboration-working-together-cochrane) and PRISMA (23, 24). One PICO question was formulated. The following documentary typologies were included: papers and review articles on the topic of interest in the study. The rest of the typologies were excluded: letters to the editor, comments, opinions, perspectives, guides and regulations, opinion web pages, bibliographic selections, cases or case series, and summaries or proceedings of conferences or symposiums. Only studies published in scientific journals were included, since, having passed a peer review process, they are more reliable. The adaptation of the selected articles to the purpose of the study and the inclusion criteria to increase the reliability and security of the process was carried out by two authors of the work independently. When there were doubts about its inclusion when reviewing the title, abstract, and keywords of the article, the full text of the document was reviewed, and if there was still a discrepancy between the two authors, a third party was incorporated to arbitrate the decision of its inclusion or exclusion. The location, selection of articles, both those included and those eliminated, and the cause of their elimination in the screening and selection phase are indicated in the flow chart in Fig. 1 in accordance with the PRISMA statement.23,24

Data extractionFrom the titles, abstracts, keywords, or the complete article (in some cases from the supplementary material of the document), depending on the case and in relation to the questions of interest, the data were extracted as they were found in the works when reviewing them, and so they are included in Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

| Article title | Reference [number in text] | Participants (PICOS) | Interventions (PICOS) | Comparators (PICOS) | Outcomes (PICOS) | Study design (PICOS) | Other study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airway-Occluding Mucus Plugs and Mortality in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | Díaz et al., 2023. Jun 6; 329 (21): 1832–9. doi:10.1001/jama. 023.2065 [17] | N: 4363 patients were included in this study. | To determine whether airway mucus plugs identified on chest computed tomography (CT) were associated with increased all-cause mortality. | Association Between Mucus Plug Score and All-Cause Mortality.Mucus plugs score (No. of lung segments with mucus plugs)0 (n=2585) 1–2 (n=953)≥3 (n=825) vs. Mortality rate %. | - Mucus plug score category (No. of lung segments with mucus plugs), No. (%)0 (n=2585) 1–2 (n=953)≥3 (n=825).- Current smoker, No. (%) Mucus plug score 0: 1155/2584 (44.7%); Mucus plugs score 1–2: 383/953 (40.2%) 347/824 (42.1%).- Pack-years of smoking, median (IQR) 44.3 (33.2–64) 46.1 (35.0–65.7) 47.6 (35.0–67.6).Compared with participants without mucus plugs, those with mucus plugs in 3 or more lung segments had a greater pack-year history of smoking. | Observational retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of patients with a diagnosis of COPD-Gene study | Participants without mucus plugs vs. those with mucus plugs in 3 or more lung segments were older and more likely to be female and non-Hispanic white, more chronic bronchitis, more current asthma, worse BODE index, lower FEV1, greater airway wall thickness, and higher percentage of emphysema on CT scans. During a median follow-up of 9.5 years (IQR, 5.0–12.2 years),1769 participants (40.6%) died. The mortality rate in participants with no mucus plugs was 34.0% (95% CI, 32.2–35.8%), 46.7% (95% CI, 43.5–49.9%) in participants with mucus plugs in 1–2 lung segments, and 54.1% (95% CI, 50.7–57.4%) in those with mucus plugs in 3 or more lung segments. The mortality probability was highest among participants with mucus plug scores of 3 or more as shown both in unadjusted and adjusted plots. The mortality rates increased across both COPD GOLD stages and mucus plug categories. When the model was adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, BMI, pack-years smoked, current smoking status, FEV1, and CT measures of emphysema and airway wall thickness, the presence of mucus plugs was significantly associated increased risk of death (score 1–2 vs 0: adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.15 [95% CI, 1.02–1.29]; score ≥3 vs 0: aHR, 1.24 [95% CI, 1.10 1.41]) compared with participants without mucus plugs. |

| Computed tomography mucus plugs and airway tree structure in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Associations with airflow limitation, health-related independence and mortality | Tanabe et al. Respirology. 2024 Nov; 29 (11): 951–61. doi: 10.1111/resp.14776. [27] | N: 295 | The aim of this study was to explore whether greater mucus plugs in middle-sized and large airways visible on CT were associated with lower baseline lung function and more severe symptoms and with future rates of loss of health-related independence and mortality irrespective of emphysema severity, airway wall remodeling and tree morphology | Examine whether mucus plugs were associated with (vs.) airflow limitation and clinical outcomes independent of another airway structural changes and emphysema. | Kyoto–Himeji cohort: No (score=0): Low (score=1, 2) High (score ≥3)Respectively in current smoker, n (%) 19 (20.7) 8 (20.0) 23 (34.3) p=0.10Respectively: Smoking pack-year 63.4 (31.8) 56.3 (27.9) 59.4 (32.2) p=0.45Hokkaido cohort: Current smoker, n (%) 11 (23.4) 7 (35.0) 8 (27.6) p=0.62Smoking pack-year 56.6 (22.4) 69.6 (39.6) 63.2 (25.3) p=0.20 | Retrospective analysis of two prospective observational cohorts: Kyoto–Himeji cohort and Hokkaido COPD cohort | 67 (34%) and 29 (30%) of the Kyoto–Himeji and Hokkaido cohorts, respectively, had high mucus scores (score ≥3).High mucus score and low TAC were independently associated with airflow limitation after adjustment for WA% and emphysema. In multivariable models adjusted for WA% and emphysema, TAC, rather than mucus score, was associated with a greater rate of loss of independence, whereas high mucus score, rather than TAC, was associated with increased mortality. |

| Association between automatic AI-based quantification of airway-occlusive mucus plugs and all-cause mortality in patients with COPD | Van der Veer et al. Thorax. 2024 Dec 5: thorax-2024–221928. doi: 10.1136/thorax-2024–221928. [28] | N: 9399 | The aim of the study was assessed the relationship between artificial intelligence-quantified mucus plugs on chest CTs and all-cause mortality. | Association between mucus plugs vs. all-cause mortality | Mucus plugs score: 0 (n=7200) 1–2 (n=1535) ≥3 (n=664). Respectively:- Current smoker, No. (%) 3901 (54.2%) 747 (48.7%) 291 (43.8%)- Pack-years of smoking, median (IQR)37.6 (25.9–51.7) 44.0 (32.5–63.3) 47.4 (34.7–68.3) | Observational retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of patients with a diagnosis of COPD-Gene study | Authors found a significant positive association, particularly for those with COPD GOLD stages 1–4, with HRs of 1.18 for 1–2 mucus-obstructed bronchial segments and 1.27 for ≥3 obstructed segments. |

| Airway-occluding Mucus Plugs and Cause-specific Mortality in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | Mettler et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024 Jun 15; 209 (12): 1508–10. doi:10.1164/rccm.202401-0121LE [29] | N: 3864 | Authors analyzed the associations of mucus plug score categories (0, 1/2, 31) and specific causes of death (respiratory, cardiovascular, and cancer) | Association between mucus plugs Vs specific causes of death | The mean pack-years of smoking history were 51.8 +/- 27, and 42% were still smoking at the time of enrolment.No results in smokers or pack-years. | Observational retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of patients with a diagnosis of COPD-Gene study | The 10-year cumulative cause-specific mortality rates were as follows: For mucus plug score 0 (n=2297), respiratory 13% (95% confidence interval [CI], 12–15%); cardiovascular 5.7% (95% CI, 4.7–6.9%); and cancer 4.8% (95% CI, 3.8–5.9%); for score 1/2 (n=833), respiratory 22% (95% CI, 18–25%); cardiovascular 7.3% (95% CI, 5.6–9.3%); and cancer 4.8% (95% CI, 3.8–5.9%); for score 31 (n=734), respiratory 29% (95% CI, 25–32%); cardiovascular 7.9% (95% CI, 5.8–10%); and cancer 8.1% (95% CI, 6.2–10%).In adjusted models, compared with participants without mucus plugs, those with mucus plugs had increased hazards of respiratory and cancer deaths. The adjusted hazard ratio (aHRs) for respiratory mortality were 1.13 (95% CI, 0.91–1.41; p=0.3) for mucus plugs score 1/2 and 1.36 (95% CI, 1.10–1.69; p=0.005) for score 31. The aHRs for cardiovascular mortality were 1.35 (95% CI, 0.96–1.91, p=0.089) for score 1/2 and 1.27 (95% CI, 0.87–1.85; p=0.2) for score 31. The aHRs for cancer mortality were 1.26 (95% CI, 0.85–1.88; p=0.3) for score 1/2 and 1.80 (95% CI, 1.23–2.63; p=0.002) for score 31 |

| Silent Airway Mucus Plugs in COPD and Clinical Implications | Mettler et al. Chest. 2024 Nov; 166(5): 1010–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.11.033. [32] | N: 4363 | Research Question: In patients with COPD, what are the risk and protective factors associated with silent airway mucus plugs? Are silent mucus plugs associated with functional, structural, and clinical measures of disease? | Silent mucus plugs vs. symptomatic mucus plugs: clinically significant.Active smokers, packs years associated | - Silent Mucus Plugs (SMP) (n=627)>SymptomaticMucus Plugs (SYMP) (n=1151). p value- Pack-years, y: SMP: 51.1±27.8. SYMP: 54.0±28.3. p .038- Smoking status: p<.001. Previously smoked: SMP: 468 (74.6). SYMP: 580 (50.4). Active tobacco use: SMP: 159 (25.4) SYMP: 571 (49.6)Compared with those with symptomatic mucus plugs, those with silent mucus plugs were more likely older, female, and not currently smoking with fewer pack-years.In both male and female participants, people who previously smoked were less likely to have symptoms of cough or phlegm than people with active tobacco use.In the multivariable model, the risk factors of silent mucus plugs (vs symptomatic mucus plugs) were older age, female sex, and Black race, whereas current smoking status and history of asthma were protective factors (i.e., associated with symptomatic mucus plugs rather than silent mucus plugs). BMI, pack-years, and history of congestive heart failure was not associated with the odds of silent mucus plugs in the multivariable model. | Observational retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of patients with a diagnosis of COPD-Gene study | Compared with those with symptomatic mucus plugs, those with silent mucus plugs had higher FEV1% predicted, higher percentage of emphysema, and lower airway wall thickness on CT scans, and lower SGRQ scores in all domains.Participants without mucus plugs: In a multivariable model, male sex, non-Hispanic White race, higher BMI, current smoking status, more pack-years, and history of asthma were significantly associated with increased odds of having cough or phlegm symptoms |

| Mucus Plugs and Emphysema in the Pathophysiology of Airflow Obstruction and Hypoxemia in Smokers | Dunican et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15; 203 (8): 957–68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2248OC. [25] | N: 400 | The aim of the study was relating image-based measures of mucus plugs and emphysema to measures of airflow obstruction and oxygenation in patients with COPD. | Mucus plugs and emphysema vs. airflow obstruction and oxygenation in patients with COPD. Active smokers vs. no | Mucus plugs were highly prevalent in smokers.Among the 400 ever-smokers, 229 (57%) had mucus plugs and 207 (52%) had Emphysema.The relationships between mucus plug score and lung function outcomes were strongest in smokers with limited emphysema (p<0.001). Compared with smokers with low mucus plug scores, those with high scores had worse COPD Assessment Test scores (17.4±7.7 vs. 14.4±13.3), more frequent annual exacerbations (0.75±1.1 vs. 0.43±0.85), and shorter 6-minute-walk distance (329±115 vs. 392±117m) (p<0.001). | Prospective observational study | |

| Luminal Plugging on Chest CT Scan Association With Lung Function, Quality of Life, and COPD Clinical Phenotypes | Okajima et al. Chest. 2020 Jul; 158 (1): 121–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.12.046 [26] | N: 100 smokers without COPD and N: 400 smokers with COPD | Authors aimed to examine the associations of chest CT scan-identified luminal plugging with lung function, health-related quality of life, and COPD phenotypes. | Mucus plugs vs. lung function, quality of life and COPD phenotypes | Subjects Without Luminal Plugging (NoLP) (n=389)Subjects With Luminal Plugging (WLP) (n=111). p valuePack-years smoked: NoLP: 46±23; WLP: 55±35 .002Current smoking status, yes: NoLP: 45 WLP: 41. p .39 | Observational retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of patients with a diagnosis of COPD-Gene study | |

| Mucus Plugs as Precursors to Exacerbation and Lung Function Decline in COPD Patients | Jin et al. Arch Bronconeumol. 2024 Jul 27: S0300-2896(24)00282–5. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2024.07.017. [31] | N: 623 | The present study aimed to investigate the influence of mucus plugs in chest computed tomography (CT) on clinical outcomes, including AE-COPD and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) decline, in COPD patients over a 5-year period. | Mucus plugs vs. smokers, exsmokers and never smokers Mucus plugs score vs. exacerbationsMucus plugs vs. decline in FEV1 over a 5-year period | Total population- Never smokers (NS)Total (n=623) NS: n (%): 93 (14.9)No Mucus Plug Group(n=347). NS: 58 (1,6,7)Mucus Plug Group (n=276): NS: 35 (12.7)- Ex-smoker (ES)Total (n=623) n (%) ES: 278 (44.6)No Mucus plugs (n=347). ES: 145 (41.8)Mucus plugs group (n=276). ES: 133 (48.2)- Current smoker (CS),Total (n=623) CS: 25. 2 (40.4)No Mucus plugs (n:347). CS: 144 (41.5) Mucus plugs (n=276). CS: 108 (39.1)NSPack-years for ever-smokers, median (IQR): 35 (20–50) 30 (15–45) 40 (20–50) p=0.015, in Total (n=623)No Mucus Plug Group(n=347)Mucus Plug Group(n=276), respectively. | Retrospective observational study | - The mucus plugs group showed higher rates of moderate-to-severe (0.51/year vs. 0.58/year, p=0.035), severe exacerbations(0.21/year vs. 0.24/year, p=0.032), and non-eosinophilic exacerbations (0.45/year vs. 0.52/year, p=0.008).- Mucus plugs were associated with increased hazard of moderate-to-severe (adjusted HR=1.502 [95% CI1.116–2.020]), severe (adjusted HR=2.106 [95% CI, 1.429–3.103]), and non-eosinophilic exacerbations(adjusted HR=1.551 [95% CI, 1.132–2.125]).- Annual FEV1 decline was accelerated in the mucus plug group (̌-coefficient=−62 [95% CI, −120 to −5], p=0.035). |

| Airway Mucus Plugs on Chest Computed Tomography Are Associated with Exacerbations in COPD | Wan et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024 Oct 29. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202403-0632OC. [30] | N: 3250 in COPDGene and N: 1716 participants in ECLIPSE. | Whether mucus plugs are associated with prospective exacerbations. | Total number of adverse events (AEs), defined as new or increased respiratory symptoms (cough, phlegm, dyspnea) which required treatment with systemic steroids and/or antibiotics, either in the outpatient, emergency room, or inpatient setting, over time.Mucus plugs vs. exacerbation: Increased or decreased risk of exacerbation vs current and former smoker in COPDgene and ECLIPSE group | COPDgene- Current smoker a favor risk: 1.03 (0.97–1.10)- Former smoker a favor risk: 1.13 (1.08–1.18)ECLIPSE GROUP- Current smoker a favor risk: 1.05 (0.94–1.16)- Former smoker a favor risk: 1.10 (1.02–1.16)An increased risk for future AEs among former, relative to current, smokers with mucus plugs was observed in both cohorts | Observational retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of patients with a diagnosis of COPD-Gene study and ECLIPSE a multi-center observational study. | Among 3250 participants in COPDGene (mean±SD age 63.7±8.4 years, FEV150.6%±17.8% predicted, 45.1% female) and 1716 participants in ECLIPSE (age 63.3±7.1 years, FEV1 48.3%±15.8% predicted, 36.2% female), 44.4% and 46.0% had mucus plugs, respectively |

The presentation of the results of the primary studies, obtained through a systematic and reproducible methodology, was carried out qualitatively and quantitatively. To comply with the key aspects and appropriate steps that must be considered when publishing an SRL and an MA in a biomedical journal, we have adhered to the PRISMA statement (Appendix 1).23,24

Statistical analysisReview Manager (RevMan version 5.4, Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK) was used to conduct the meta-analysis of included studies. We compared current and former using odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals, pooled with a random-effects model, to determine their association with mucus plugs formation. The Mantel–Haenszel odds ratio was calculated for primary and secondary endpoints where applicable. Heterogeneity was measured with the I2 statistic (≥50% indicating significant heterogeneity). Publication bias was visually assessed via the funnel plot. A p-value<0.05 (two-tailed) was deemed statistically significant. Sensitivity analyses were carried out to determine the association of current or former smokers with a composite of non or low number (0–2) of mucus plugs versus a high number (>3), and ever or non-smokers with mucus plugs formation in general. To assess the robustness of the meta-analytic findings, we initially considered performing a meta-regression adjusting for key covariates such as age or tobacco exposure measured in pack-years. However, due to the limited number of studies ultimately included in the analysis, meta-regression was not conducted. Nonetheless, we performed a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis to evaluate the influence of each individual study on the pooled estimate.

We have conducted a structured risk of bias analysis using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (Appendix 2: Table of NOS analysis), as none of the included studies involved intervention by design. The analysis focused on the exposure to a risk factor and the subsequent development of a complication.

ResultsSelection of studiesAfter the search for articles carried out in the different databases was analyzed and after eliminating duplicate documents, 161 articles were identified for manual review (Fig. 1). In the screening phase, a total of 109 articles met the exclusion criteria and 43 with lack of adaptation to the purpose of the study, and then 9 documents were finally chosen. These 9 articles17,25–32 were included in the SRL (Table 1), and 6 of them were part of the MA17,25–28,31 (Table 1 with bold).

Study characteristicsTable 1 shows the participant data for each of the studies: number of patients, type of intervention, comparison made in the article, its outcome, and type of study (following the acronym PICOS). Other interesting results from the analyzed works have been added in an added column.

Risk of bias in studiesRisk of bias in the individual studies included in the MA: four of the included studies17,26,28,31 are retrospective observational studies of prospectively collected data. One of the studies27 was a retrospective analysis of two prospective observational cohorts, and one was a prospective observational study25 (Table 1). Therefore, in these studies, the biases common to observational studies may have occurred. Observational studies, including retrospective analyses of prospectively collected data, can be biased due to a number of factors, including: Selection bias, information bias, confounding, recall bias, imbalances between comparison groups, loss to follow-up and research biases. Observational cohort studies can be biased in many ways, including selection bias, information bias, and confounding. Not all of the included studies adjusted the odds ratio in the article, with the consequent possible loss of precision.

The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the overall results of the meta-analysis were generally robust. However, the exclusion of the study by Okajima notably altered the pooled effect estimate, suggesting that this study contributes substantially to the observed heterogeneity.

An NOS score above 7 is considered indicative of low risk of bias; it is important to acknowledge that the inherently observational design of the included studies limits the ability to account for all potential confounding variables. Some studies addressed a broader range of confounders than others, which is reflected in their higher the NOS scores. We have added NOS Table as supplementary material (Appendix 2).

All included studies were observational in design, and thus the initial certainty of evidence was rated as low. Given the substantial heterogeneity (I2>90%) and potential risk of bias in several studies, the certainty was further downgraded. However, the presence of a consistent dose-response gradient between cumulative smoking exposure (pack-years) and the presence of mucus plugs supports upgrading the evidence. Overall, the certainty of evidence was rated as low.

Synthesis of resultsIn the EPISCAN II study,33 the prevalence of COPD in Spain measured by post-BD fixed ratio FEV1/FVC<0.7 was 11.8% (95% C.I. 11.2–12.5), 14.6% (95% C.I. 13.5–15.7) in males, and 9.4% (95% C.I. 8.6–10.2) in females, with a great underdiagnosis of 74.7%. Excess mucus production, hypersecretion, and decreased clearance are the hallmarks of mucus dysfunction, a central pathology in patients with COPD that causes buildup in the airways as plugs.17 Mucus plugs that completely block the airways are seen in 25–67% of computed tomography (CT) scans of people with COPD. These plugs are linked to reduced exercise capacity, lower oxygen saturation, and airflow obstruction. In individuals with COPD, 67% have mucus plugs that persist at 1 year and 73% at 5 years. Up to 30% of patients with COPD who have mucus plugs on CT report no cough or sputum.25,26

Mucus plugs and mortalityDiaz et al.17 investigated whether airway mucus plugs seen on chest computed tomography (CT) were linked to higher mortality from all causes. The authors discovered that a total of 2585 (59.3%), 953 (21.8%), and 825 (18.9%) participants had mucus plugs in 0, 1 to 2, and 3 or more lung segments, respectively. The corresponding mortality rates were 34.0% (95% CI, 32.2–35.8%), 46.7% (95% CI, 43.5–49.9%), and 54.1% (95% CI, 50.7–57.4%). The presence of mucus plugs in 1–2 vs. 0 and 3 or more vs. 0 lung segments was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio of death of 1.15 (95% CI, 1.02–1.29) and 1.24 (95% CI, 1.10–1.41), respectively. According to the authors, there was a higher all-cause mortality rate among individuals with COPD who had mucus plugs obstructing medium- to large-sized airways, compared with patients without mucus plugging on chest CT scans. Tanabe et al.27 found that in patients with COPD, lower FEV1 was linked to more mucus plugging in large to medium-sized airways, regardless of the severity of emphysema or central wall remodeling. Furthermore, the authors’ findings demonstrate how the patient's symptoms, loss of independence, and mortality risk are influenced by mucus plugging and total airway count. The same was found by van der Veer et al.28 across various COPD severities, confirming the association of mucus plugs with mortality, likely mediated through inflammation, infection, and ventilation/perfusion mismatch. Mettler et al.29 hypothesized that the occlusion of airways by mucus plugs would be related to respiratory causes of death, so they included participants of the COPDGene study, and mucus plugs were surveyed in medium-sized to large airways (lumen diameter of 2–10mm) on baseline volumetric CT scans. The authors defined mucus plug score as the number of pulmonary segments with mucus plugs (ranging from 0 to 18) and categorized them into three groups as previously described17: 0, 1/2, and 3+. So, the study explores cause-specific mortality in participants with COPD and airway-occluding mucus plugs and highlights that airway mucus plugs may be associated with respiratory and cancer deaths in this population.

Mucus plugs and increased risks of exacerbations in COPD patients and lung function impairmentsAcute exacerbations are important occurrences in the natural course of COPD that are linked to a reduction in lung function and a higher risk of mortality. As it has been known for years, chronic cough and sputum production are associated with frequent COPD exacerbations, including severe exacerbations requiring hospitalisations.16 As stated above, mucus plugs are an airway pathologic process in COPD that can be detected and quantified on CT scans. Examining how airway-obstructing mucus plugs affect subsequent exacerbations is clinically relevant because mucus plugs may be reversible with medical therapy. This was the aim of Wan et al.,30 who found in COPD-Gene and ECLIPSE studies that 44.4% and 46% had mucus plugs, respectively. The incidence rates of exacerbations were 61 (COPD-Gene) and 125.7 (ECLIPSE) per 100 person-years. Relative to those without mucus plugs, the presence of 1–2 and ≥3 mucus plugs were associated with increased risk (adjusted rate ratio, aRR [95% CI]=1.07 [1.05–1.09] and 1.15 [1.1–1.2] in COPD-Gene; aRR=1.06 [1.02–1.09] and 1.12 [1.04–1.2] in ECLIPSE, respectively) for prospective moderate-to-severe exacerbations. The presence of 1–2 and ≥3 mucus plugs was also associated with increased risk for severe AEs during follow-up (aRR=1.05 [1.01–1.08] and 1.09 [1.02–1.18] in COPD-Gene; aRR=1.17 [1.07–1.27] and 1.37 [1.15–1.62] in ECLIPSE, respectively). So, they concluded that CT-based mucus plugs are associated with an increased risk for future COPD AEs. In another study by Jin et al.,31 they found that mucus plugs are associated with increased risks of exacerbations, particularly non-eosinophilic, and accelerated FEV1 declines over 5 years. So, they also identified the potential prognostic value of mucus plugs on future exacerbation risks and lung function decline trajectories.

Okajima et al.26 aimed to examine the associations of chest CT scan-identified luminal plugging with lung function, health-related quality of life, and COPD phenotypes. They found that CT scan-identified luminal plugging was significantly associated with FEV1% predicted (estimate, −6.1%; SE, 2.1%; p=.004) in adjusted models. Authors’ propose that the robust association between luminal plugging and FEV1 suggests that luminal plugging is in the causal line of lung function impairment. Dunican et al.25 found that mucus plug score, and emphysema percentage were independently associated with lower values for FEV1 and peripheral oxygen saturation (p<0.001). The relationships between mucus plug score and lung function outcomes were strongest in smokers with limited emphysema (p<0.001). Compared with smokers with low mucus plug scores, those with high scores had worse COPD assessment test scores (17.4±7.7 vs. 14.4±13.3), more frequent annual exacerbations (0.75±1.1 vs. 0.43±0.85), and shorter 6-min-walk distance (329±115 vs. 392±117m) (p<0.001). Authors conclude symptomatically silent mucus plugs are highly prevalent in smokers and independently associate with lung function outcomes. Mettler et al.32 in a study with 1739 participants, found that 627 (36%) had airway mucus plugs identified on CT scan. Among those without cough or phlegm, silent mucus plugs (vs. absence of mucus plugs) were associated with worse 6-min walk distance, worse resting arterial oxygen saturation, worse FEV1% predicted, greater emphysema, thicker airway walls, and higher odds of severe exacerbation in the past year in adjusted models.

Mucus plugs and other associationsAkhoundi et al.34 found that mucus plugs were associated not only with increased severity of COPD but also with higher pulmonary arterial occlusion index and altered clot distribution within the pulmonary artery tree. The authors draw the conclusion that these results highlight the significance of identifying mucus plugs as a crucial factor in the assessment and treatment of COPD, as they may have an impact on vascular remodeling, thrombotic risk management, and the severity of the disease.

Findings of the analysis carried outWe found that subjects who had never smoked had a lower rate of mucus plugs when compared to active and ex-smokers (OR 0.08 [CI 95% 0.06, 0.12]) (Fig. 2). COPD patients who are smokers and ex-smokers tend to have more mucus plugs than non-smokers. In the study by Dunican et al.,18 the median mucus plug score was 0 in healthy non-smoking control subjects, while it was 3 in ex-smokers with airflow obstruction. Furthermore, 67% of all COPD patients had a mucus plug score greater than 0. The study by Van der Veer et al.28 confirmed associations with higher mortality in the COPD-Gene cohort using automated mucus plug analysis, consistent with visual scoring methods. In the control group of 107 non-smokers, they detected mucus plugs in 6 participants (5.6%), while the prevalence of any mucus plug in GOLD stages 1 to 4 (18.1–73.8%) was substantially higher than that observed in subjects with preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) group (14.7%) and GOLD 0 (8.9%) participants and also substantially higher than that observed in nonsmokers (5.6%). These findings clearly suggest a higher prevalence of mucus plugs in people with COPD who have a history of smoking compared to nonsmokers.

When comparing subjects with and without mucus plugs between current smokers vs. ex-smokers, we found that ex-smokers had a higher rate of mucus plugs than current smokers (OR 1.12 [CI 95% 1.02, 1.24]) (Fig. 3). Similarly, when comparing subjects without mucus plugs or with a low mucus plug score (0–2) with a high mucus plug score (>3) between current smokers vs. ex-smokers, we found that ex-smokers had a higher mucus plug score than current smokers (OR 1.19 [CI 95% 1.08, 1.32]) (Fig. 4). Like in our study, similar findings have been reported by Dunican et al.,18 among all patients with COPD, 67% had a mucus plugging score greater than 0. This prevalence was similar between former smokers (70%) and current smokers (64%; p=0.96). Therefore, according to this study, the prevalence of mucus plugging does not differ significantly between current and former smokers with COPD.

Some of the studies included in this paper suggest that ex-smokers may have a higher proportion of mucus plugs; conversely, other studies explicitly state that there is no significant difference in the prevalence of mucus plugs between current and former smokers (most of these studies have rigorously adjusted for confounders): Diaz et al.17 found that a higher proportion of ex-smokers were present in the mucus plug groups. Mettler et al.32 found that being an ex-smoker was a risk factor for silent mucus plugs (those without cough or phlegm symptoms) compared with symptomatic mucus plugs. Jin et al.31 found that, in the total population, the mucus plug group had a higher percentage of ex-smokers and a lower percentage of current smokers compared with the non-mucus plug group. Okajima et al.26 and Van der Veer et al.28 also found a higher prevalence of ex-smokers in the group with mucus plugs. In contrast, Dunican et al.25 explicitly found that the prevalence of mucus plugs was “similar in ex-smokers and active smokers”, with Tanabe et al.27 finding a higher number of plugs in active smokers.

DiscussionIn our study, we found that subjects who have never smoked have a lower rate of mucus plugs than those who have smoked. Furthermore, we found that ex-smokers with COPD have a higher rate of mucus plugs than current smokers with COPD. Also, when comparing subjects without mucus plugs with those with a low mucus plugs score and comparing current and ex-smokers with a high mucus plugs score, we found that ex-smokers had a higher mucus plugs score than current smokers. This partially answers the hypothesis raised, as smokers do have a higher rate of mucus plugs compared to non-smokers, but ex-smokers have a higher rate of mucus plugs compared to current smokers. What is unquestionable is that smoking causes COPD4 and that smoking also promotes the development of mucus plugs. In subjects diagnosed with COPD, the presence of mucus plugs is associated with lower lung function, worse quality of life, higher all-cause mortality, and higher pathogenesis, progression, and exacerbations of COPD.

From the studies analyzed, we cannot infer that ex-smokers have more severe COPD compared to current smokers. However, some sources offer information suggesting differences in certain aspects of the disease between these groups. In the study by Wan et al.,30 a higher risk of future exacerbations was observed among ex-smokers with mucus plugs compared to current smokers with mucus plugs in both cohorts analyzed (COPD-Gene and ECLIPSE). This suggests that while the presence of mucus plugs is associated with an increased risk of exacerbations in general, this association may manifest differently in ex-smokers and current smokers. On the other hand, the study by Dunican et al.25 found that the prevalence of a high mucus plug score was similar in ex-smokers and current smokers with COPD. The mucus plug score is related to airflow obstruction. It is important to note that COPD severity is assessed by several factors, including lung function (measured by FEV1), symptoms, and exacerbation history.17 While the presence of mucus plugs and the risk of exacerbations are important components of COPD, do not present a direct and comprehensive comparison of overall COPD severity between former smokers and current smokers. A recent study35 that focuses on differences in COPD-related outcomes between never smokers, former smokers, and current smokers found that never smokers have a better prognosis and fewer symptoms than both current and former smokers with COPD. Authors found no differences in the number of moderate exacerbations during the last year prior between the 3 smoking groups; however, severe exacerbations were more common among former and current smokers as compared to never smokers. Liu et al.,36 in a study whose aim was to search for differences in the clinical characteristics between ex-smokers and current smokers with COPD, found that compared with current smokers, the ex-smokers were older; had heavier dyspnea, had more severe airflow limitation; had fewer pack-years; had a shorter smoking duration; and had a higher proportion of subjects in the GOLD E group. The aim of the study of Josephs et al.37 was to quantify smoking status in a large and representative clinically defined UK primary care COPD cohort and to explore the relationship between smoking status and clinical outcomes, so they found the same as the previous work that ex-smokers and never-smokers were significantly older than active smokers. Besides in the work of Josephs et al.37 they found that ex-smokers and never-smokers were more overweight, had less severe airflow obstruction and had a greater number of comorbidities. In another study Alter et al.38 found in patients with COPD that smokers were younger than ex-smokers (mean 61.5 vs 66.0 y), had a longer duration of smoking but fewer pack-years, a lower frequency of asthma, higher forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1, 59.4 vs. 55.2% predicted), and higher functional residual capacity (FRC, 147.7 vs 144.3% predicted). Summarizing the previous studies: ex-smokers are generally older than current smokers, have smoked for a shorter duration of time, have fewer pack-years than current smokers, have more severe airflow limitation and airway obstruction (except in Josephs’ work37 where they have a lesser severity of airflow obstruction), have a higher proportion of GOLD group E, have heavier dyspnea and more severe airflow limitation than current smokers, and may have intermittent cough, phlegm, and wheeze. Current smokers have more lung hyperinflation.35–38

Other questions are: Are there chemical, physical, or organoleptic differences in mucus between smokers and ex-smokers in patients with COPD? Does bronchial inflammation persist after quitting smoking in patients with COPD? Mucus consists of mucins, DNA, lipids, ions, proteins, cells and cellular debris, and water.1,39 The characteristics of bronchial mucus in smokers undergo several significant alterations, many of which, as we know, can contribute to the development of chronic respiratory diseases such as chronic bronchitis and COPD. Cigarette smoke induces changes in the airway epithelium, including hyperplasia and hypertrophy of goblet cells in the large airways, leading to a significant increase in epithelial mucin reserves; alteration in the type of mucins with differences between smokers and non-smokers with or without COPD; dysfunction of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; more concentrated and viscous mucus; alteration of mucociliary clearance; and the release of inflammatory mediators, in addition to damage to the DNA of bronchial epithelial cells inhibiting their repair processes.39–42 Even in ex-smokers with COPD, altered epithelial responses have been observed. Some differences in mucus characteristics have been found between smokers and ex-smokers with COPD: Verra et al.43 investigated ciliary abnormalities in the bronchial epithelium of smokers, ex-smokers, and non-smokers, and although they did not focus exclusively on patients with COPD, they found that smoking status (current or former) was associated with differences in ciliary function, which in turn may affect mucus clearance. De Boer et al.44 found that CCL2 and CXCL8 mRNA and protein expression was significantly higher in bronchiolar epithelium from ex-smokers with COPD compared to ex-smokers without COPD. CCL2 and CXCL8 are chemokines involved in inflammation, suggesting that there may be differences in the inflammatory profile of the bronchial epithelium between these ex-smokers, which could influence mucus characteristics. This suggests that inflammatory processes persist in the airway epithelium even after smoking cessation, which could influence long-term mucus characteristics. Fuke et al.45 found increased CCL3 (MIP-1α) mRNA expression in the bronchiolar epithelium of smokers with COPD compared with smokers without COPD and nonsmokers. This observation indicates that active smoking in the presence of COPD is associated with increased levels of this inflammatory chemokine in the epithelium. Furthermore, a study by Kirkham et al.46 found that MUC5AC was the predominant mucin in the sputum of smokers, whereas MUC5B was more abundant in the sputum of patients with COPD. Histopathological analysis revealed increased expression of MUC5B in the bronchiolar lumen and MUC5AC in the bronchiolar epithelium of patients with COPD. These differences in mucin types could affect the physical and chemical properties of mucus, including mucus plugs, and may differ between current and former smokers with COPD as the disease progresses and mucin expression patterns change. Therefore, we could summarize that, although the reviewed studies do not directly compare the characteristics of mucus plugs in current and former smokers with COPD, the evidence suggests that smoking induces significant changes in mucus production and composition in COPD. Even after quitting smoking, inflammatory processes persist in the airways, and mucin expression patterns differ between smokers and COPD patients, which could lead to differences in mucus plug characteristics between these groups over time.

So then, as ex-smokers generally have more severe and symptomatic COPD than active smokers, and even after quitting smoking inflammatory processes persist in the airways with mucin expression patterns differing between smokers, ex-smokers, and COPD patients, this probably could explain why ex-smokers have a higher rate of mucus plugs.

There is no doubt at this point that quitting smoking is the most significant modifiable risk factor for COPD. In COPD patients, quitting smoking is the best thing you can do to improve your health. Smoking cessation has repeatedly been shown to be associated with improvement in pulmonary symptoms and slower deterioration in lung function compared with continuous smoking, features that have been linked to improved survival. Smoking cessation seems to be the only evidence-based treatment to improve the COPD prognosis. It does not reverse respiratory function loss but decreases the annual decline in lung function, reduces symptoms of cough and sputum, reduces inflammation and lung cancer risk, improves health status, and reduces exacerbations of COPD.47 Patients who quit smoking within two years after COPD diagnosis had lower risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality relative to persistent smokers.48,49 In summary, smoking cessation improves pulmonary function, alleviates dyspnea and cough, reduces the frequency of COPD exacerbations, and lowers mortality. Merely reducing smoking does not improve pulmonary function or alleviate symptoms.

The study has obvious limitations: (a) all the articles analyzed were observational studies; there were no prospective randomized clinical trials; (b) the included studies were highly heterogeneous. This variability among the studies could have biased the comparisons; (c) publication bias was acceptable given the circumstances that almost all the studies were observational and retrospective; (d) to avoid selection bias as much as possible, we clearly defined the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the search and review in an attempt to be more objective; (e) one of the main limitations of the present study was the inability to further explore and adjust for covariates, which would have allowed for a more definitive assessment of the association—if any—between tobacco use and the formation of mucus plugs. Nevertheless, this initial attempt to synthesize the available evidence represents an important step toward establishing another potential harm associated with tobacco consumption. This is supported by biological plausibility and a probable dose-response relationship between cumulative exposure and airway damage, even following smoking cessation. Naturally, further studies specifically designed to evaluate the association between tobacco use and mucus plug formation are needed.

In conclusion, we found that subjects who have never smoked have a lower rate of mucus plugs than those who have smoked and that ex-smokers with COPD have a higher rate of mucus plugs than current smokers with COPD. In COPD patients, as is known, the presence of mucus plugs is associated with lower lung function, worse quality of life, higher all-cause mortality, and higher pathogenesis, progression, and exacerbations of COPD. Those who have never smoked have milder symptoms and a better prognosis for COPD than current and former smokers with COPD, so quitting smoking is the most significant modifiable risk factor for COPD.

Artificial intelligence involvementNone of the materials have been produced partially or totally with the aid of any artificial intelligence software or tool.

FundingThis paper was not funded.

Authors’ contributionsJIG-O: conception and design of the study, writing the core content of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. AA-A and RA-B: have proposed the search strategy for the articles in the different selected databases, they have obtained the different selected articles and they have discarded the repeated ones and carried out the first screening of them. DL-P: statistical analysis and interpretation of data, preparation and critical review of the manuscript. CAJ-R, SS-R, CR-C, MJ-G: critical review of the manuscript.

All authors approved the current version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interestJIG-O has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): Aflofarm, Adamed, Boehringer, Esteve, Neuroxpharm and Pfizer. CAJ-R has received honoraria for presentations, participation in clinical studies and consultancy from: Aflofarm, Adamed, Bial, GSK, Menarini, Neuroxpharm and Pfizer. DL-P has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, conferences attendance, participation in clinical studies and educational activities in general for the following (alphabetical order): Astra Zeneca, Aerogen, Chiesi, GSK, Menarini, Oximesa, Philips, Resmed, Sapio, Vivisol and Zambón. The rest of the authors have no conflict of interest.