Asthma is a chronic lung disease affecting individuals across all age groups, contributing to significant morbidity and mortality. Exposure to air pollutants is a major factor in both the development and exacerbation of asthma symptoms. This study reviewed the impact of key air pollutants, including nitrogen dioxide (NO2), particulate matter with a diameter ≤2.5μm (PM2.5) or ≤10μm (PM10), and ozone (O3), on asthma outcomes. Our analysis of 20 studies showed significant associations between exposure to these pollutants and increased asthma incidence and prevalence, particularly in children. Specifically, pollutants such as elemental carbon (EC), benzene, NO2, PM10, and sulfur dioxide (SO2) were found to be significantly associated with asthma development in children, while NO2 and PM2.5 were linked to asthma exacerbations in both children and adults. Additionally, hospitalizations and emergency room visits were positively correlated with exposure to PM2.5 and O3 in both children and adults, and the elderly showed significant associations with O3 exposure. Although asthma-related mortality was not directly linked to specific pollutants, a few studies indicated a broader association between exposure to pollutants like NO2 and PM2.5 and increased overall mortality. These findings highlight the importance of reducing exposure to outdoor air pollutants to mitigate asthma risk and improve public health outcomes, particularly in vulnerable populations like children and the elderly.

El asma es una enfermedad pulmonar crónica que afecta a personas de todas las edades, contribuyendo a una morbimortalidad significativa. La exposición a contaminantes atmosféricos es un factor clave tanto en el desarrollo como en la exacerbación de los síntomas del asma. Este estudio revisa el impacto de los principales contaminantes del aire, incluyendo dióxido de nitrógeno (NO2), material particulado con un diámetro ≤2,5μm (PM2,5) o ≤10μm (PM10), y ozono (O3), sobre los resultados del asma. Nuestro análisis de 20 estudios muestra asociaciones significativas entre la exposición a estos contaminantes y un aumento en la incidencia y prevalencia del asma, especialmente en niños. En particular, contaminantes como el carbono elemental (EC), el benceno, el NO2, el PM10 y el dióxido de azufre (SO2) se asociaron significativamente con el desarrollo del asma en niños, mientras que el NO2 y el PM2,5 se vinculaban con exacerbaciones del asma tanto en niños como en adultos. Además, se encontraron correlaciones positivas entre las hospitalizaciones y las visitas a urgencias con la exposición a PM2,5 y O3 en niños y adultos, y los ancianos mostraron asociaciones significativas con la exposición a O3. Aunque la mortalidad relacionada con el asma no se vinculó directamente a contaminantes específicos, algunos estudios indicaron una asociación más amplia entre la exposición a contaminantes como NO2 y PM2,5 y un aumento en la mortalidad general. Estos hallazgos resaltan la importancia de reducir la exposición a contaminantes atmosféricos exteriores para mitigar el riesgo de asma y mejorar los resultados en salud pública, especialmente en poblaciones vulnerables como niños y ancianos.

Asthma is a chronic lung disease characterized by inflammation and narrowing of the airways, usually resulting from an allergic reaction or hypersensitivity. It is a global health issue that affects people of all ages representing a significant cause of mortality and morbidity. According to the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors (GBD) study, approximately 260 million people suffer from asthma worldwide, with around 436,000 deaths attributed to asthma in 2021.1

The main clinical manifestations of asthma include wheezing, coughing, chest tightness, and shortness of breath, often triggered by a range of factors such as allergens, respiratory infections, exercise, or environmental pollutants. Asthma disease course and prognosis vary widely, from asthma symptoms resolving spontaneously (or in response to medication) to irreversible airway obstruction.2 In addition, patients may suffer acute episodes of asthma exacerbations, which worsen quality of life and may be life-threatening.3 External factors that increase the risk of exacerbation include, among others, viral infections, smoking and air.4 In fact, short-term exposure to air pollutants is closely related not only to asthma, but also to other respiratory conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), shortness of breath and wheezing, entailing high morbidity and mortality burden.5

Air pollutants may have a natural source (wildfire, volcanos, etc.) or an anthropogenic one (traffic and industrialization-related pollution). The major health-damaging air pollutants include particles of solid or liquid matter suspended in the air, known as particulate matter (PM), and gases such as ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and sulfur dioxide (SO2), among others. Particulate matter are commonly used for determining air quality and classified according to its diameters as PM2.5 (particles with a diameter ≤2.5μm), PM10 (particles with a diameter ≤10μm) and ultrafine particles (UFP) (particles with a diameter <0.1μm). Furthermore, a mix of pollutants with higher impact on respiratory system are those derived from traffic, the so-called traffic-related air pollution (TRAP).5,6 Although there has been improvement in air quality over recent decades, more than 90% of the global population lives in areas exceeding the PM2.5 air quality guidelines.7,8

There is growing body of evidence linking air pollution with asthma development and exacerbations, especially in children. In fact, asthma is the most prevalent chronic disease among children.9 Studies have also reported that prenatal exposure to outdoor air pollution may increase the risk of asthma and wheezing in children later in life.9 This impact of air pollution on asthma may be partly explained by the direct irritant and inflammatory effects of air pollutants on airways and airway hyper-responsiveness, both typical asthma features.10 The level of exposure to pollutants could have an impact on asthma development and exacerbations, since the effects of air pollution exposure may accumulate over time.11 Several meta-analyses associate outdoor air pollutants with negative impact on asthma outcomes: higher incidence and prevalence, worsening of asthma symptoms, and more hospitalizations and exacerbations.12–17 Besides its clinical impact, asthma also represents an important socioeconomic burden, with high direct and indirect health-related costs arising from the management and the associated disability.18,19

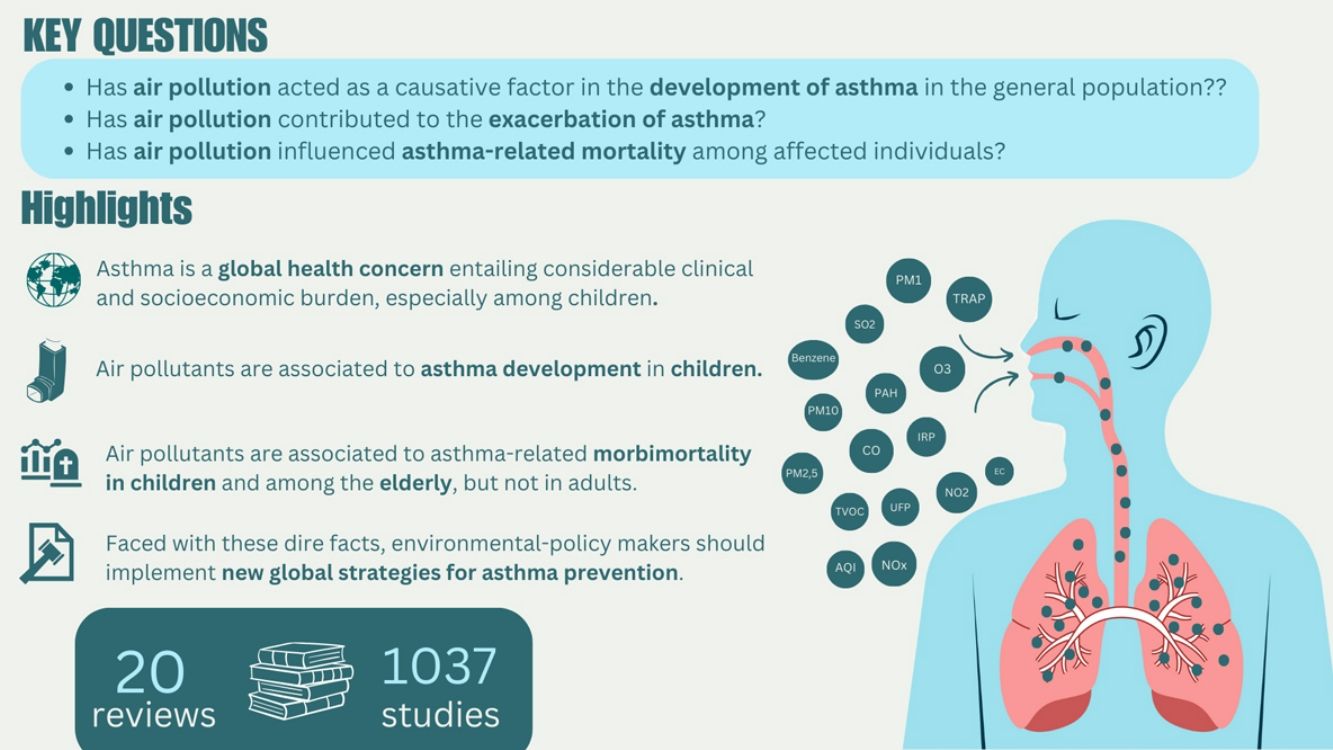

Although the relationship between air quality and asthma development, exacerbations, and mortality has been previously studied, the specific contribution of each pollutant to individual health outcomes remains unclear. Understanding the complex relationship between asthma and various air pollutants is crucial for improving patients’ quality of life and addressing public health challenges effectively. Therefore, the objective of this narrative review was to evaluate the evidence on the association between different ambient air pollutants and the incidence, exacerbation, and mortality of asthma across various age groups.

Material and methodsPECO questionThe aim of this study was to synthesize information on outdoor air pollutants and their impact on asthma following the PECO (Population, Exposure, Comparison, Outcome) approach. The target population included individuals of all ages diagnosed with asthma. Exposure was defined by the presence of common environmental air pollutants (specific details in Supplementary Table 1). In terms of comparison, scenarios with significant environmental air pollution exposure were contrasted against those without such exposure. Finally, the outcomes measured encompassed the prevalence and incidence of asthma and other respiratory diseases, the asthma development, exacerbations of asthma or other respiratory conditions, including hospitalizations and emergency room (ER) visits, and all-cause mortality.

This review aimed to evaluate the evidence supporting an association between air pollution and the asthma development in the general population, as well as its association with the exacerbation of asthma symptoms and asthma-related mortality in affected individuals.

Search strategyA systematic search of all published studies from April 2010 to November 2023 was performed in PubMed and The Cochrane Library. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed.20 In the search, key words, medical subject headings (MeSH) titles, and free-text terms for the following concepts: “pollution AND asthma AND (incidence OR mortality OR exacerbation)” were used.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaIn this review only published systematic reviews or meta-analysis providing summarized quantitative data about the impact of air pollutants on the development or exacerbation of asthma were included. Only publications in English or Spanish with accessible abstracts were considered.

Study selectionAfter an initial screening by the scientific committee, potentially eligible studies were included. Then, the titles and the abstracts of all the identified studies were assessed for their eligibility, and articles satisfying the aforementioned inclusion criteria were selected. Two primary reviewers (C.A. and I.M.) thoroughly read the papers to accurately discern whether they met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were relevant for the review.

Data extractionSubsequently, data from the selected articles were extracted by two independent reviewers (C.A and I.M.) using a standardized data collection sheet. The data extraction form was created ad hoc for this project (Supplementary Table 2).

Data analysisAll articles that incorporated statistical values from a diverse array of studies were included. In the present study, a vote-counting systematic approach was adopted, where the p-values or statistical outcomes from comparisons of multiple studies within a single review, based on relative risk (RR) or odds ratio (OR) statistics were recorded. These statistical data points served as the primary units of analysis, each representing an individual item or discrete entry in the data extraction table. Each item captures the strength of evidence for the specific comparison under investigation.

When the data extracted were not providing a specific significance p-value, but RR or OR together with an associated confidence interval was given, these were converted into approximate p-values based on the confidence provided (commonly 95%, meaning a p<0.05) to indicate the significance.

The populations from each study were grouped into predetermined age intervals: children (0–18 years), adults (19–64 years), and elderly individuals (>65 years). Additionally, the results were also analyzed in the whole population (without age-grouping). Details of pollutants and pollutants thresholds were also collected although they were considered as the same pollutant (Supplementary Table 1).

The outcomes measured in relation to asthma collected are shown in Supplementary Table 3. The outcomes were classified from the most general to the most specific to facilitate subsequent sub-analysis.

All these outcomes and sub-outcomes were classified into three broad categories: incidence of asthma, asthma exacerbation and mortality. The items were classified into two categories using the vote-counting approach, “statistically significant” (based on a p-value <0.05 or a 95% confidence interval 95% not capturing the neutral value) and “non-statistically significant” (based on a p-value >0.05 or a 95% confidence interval capturing the neutral value). Thereafter, these sub-analyses were rigorously scrutinized to explore potential influential factors affecting asthma.

Finally, these multiple evaluations were conducted for each age group (children, adults, elderly), as well as for unspecified age groups, and for the overall population.

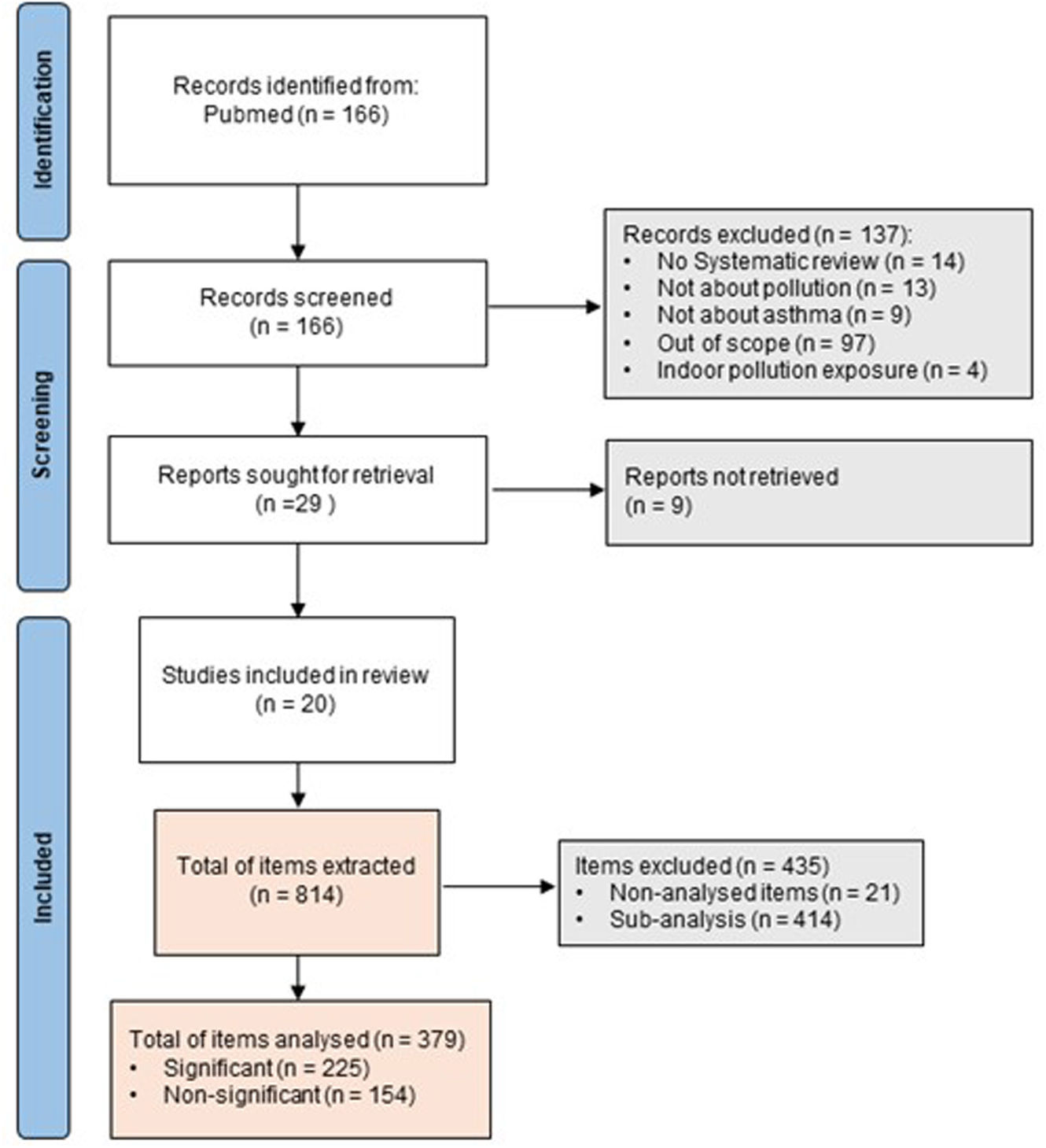

ResultsCharacteristics of the included studiesThe systematic search retrieved 166 potential studies. After an initial screening of title and abstract, 137 records were excluded. The remaining 29 articles were fully assessed for eligibility through a complete reading of the text, and among these, 9 articles were excluded. Finally, 20 studies were included in the review (Fig. 1).9,13,14,17,21–36 The list of all excluded studies along with the reasons for exclusion is included as Supplementary Table 4.

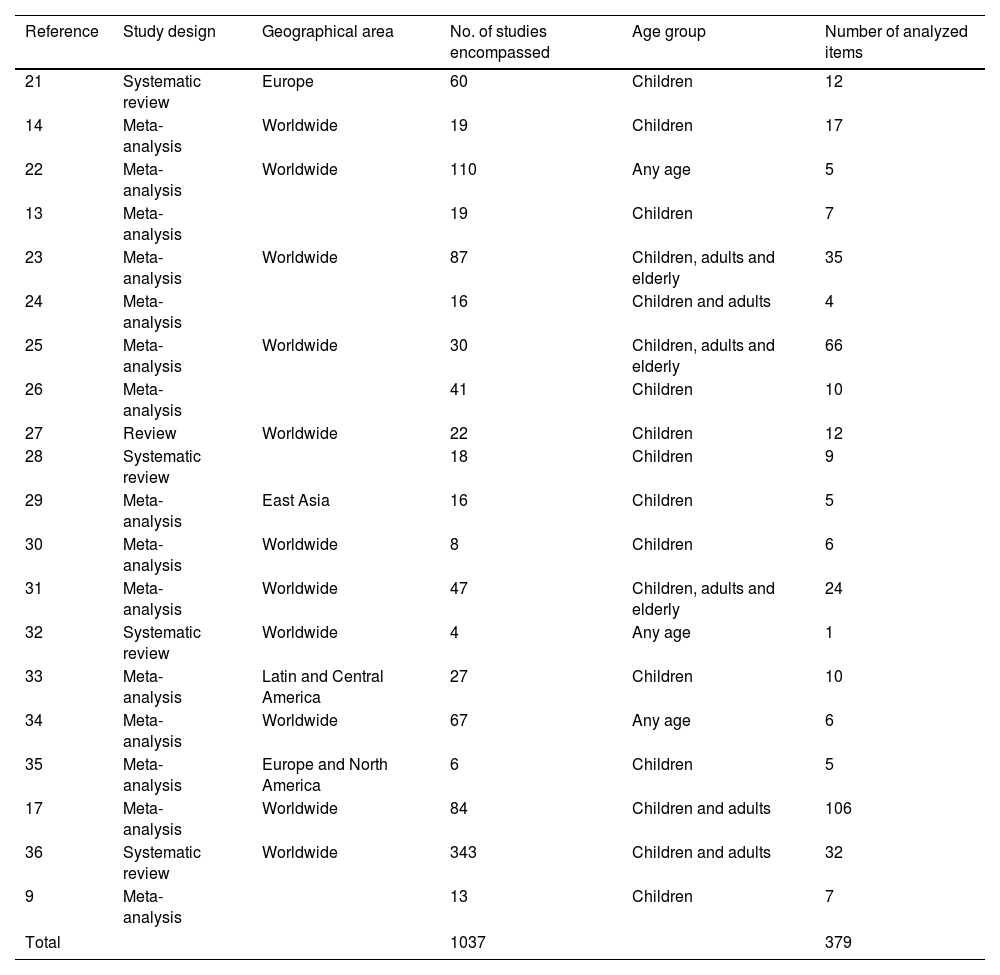

Information of the selected publications regarding the number of included studies, the number of analyzed items and age group considered is summarized in Table 1. Overall, the 20 articles encompassed 1037 studies and 814 items of information, but only 379 were considered in this analysis. The remaining items were excluded because they were not the aim of this study, did not met the PECO question or were sub-analyses exploring external factors (Supplementary Table 5).

Articles included in the data extraction step for the review.

| Reference | Study design | Geographical area | No. of studies encompassed | Age group | Number of analyzed items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | Systematic review | Europe | 60 | Children | 12 |

| 14 | Meta-analysis | Worldwide | 19 | Children | 17 |

| 22 | Meta-analysis | Worldwide | 110 | Any age | 5 |

| 13 | Meta-analysis | 19 | Children | 7 | |

| 23 | Meta-analysis | Worldwide | 87 | Children, adults and elderly | 35 |

| 24 | Meta-analysis | 16 | Children and adults | 4 | |

| 25 | Meta-analysis | Worldwide | 30 | Children, adults and elderly | 66 |

| 26 | Meta-analysis | 41 | Children | 10 | |

| 27 | Review | Worldwide | 22 | Children | 12 |

| 28 | Systematic review | 18 | Children | 9 | |

| 29 | Meta-analysis | East Asia | 16 | Children | 5 |

| 30 | Meta-analysis | Worldwide | 8 | Children | 6 |

| 31 | Meta-analysis | Worldwide | 47 | Children, adults and elderly | 24 |

| 32 | Systematic review | Worldwide | 4 | Any age | 1 |

| 33 | Meta-analysis | Latin and Central America | 27 | Children | 10 |

| 34 | Meta-analysis | Worldwide | 67 | Any age | 6 |

| 35 | Meta-analysis | Europe and North America | 6 | Children | 5 |

| 17 | Meta-analysis | Worldwide | 84 | Children and adults | 106 |

| 36 | Systematic review | Worldwide | 343 | Children and adults | 32 |

| 9 | Meta-analysis | 13 | Children | 7 | |

| Total | 1037 | 379 | |||

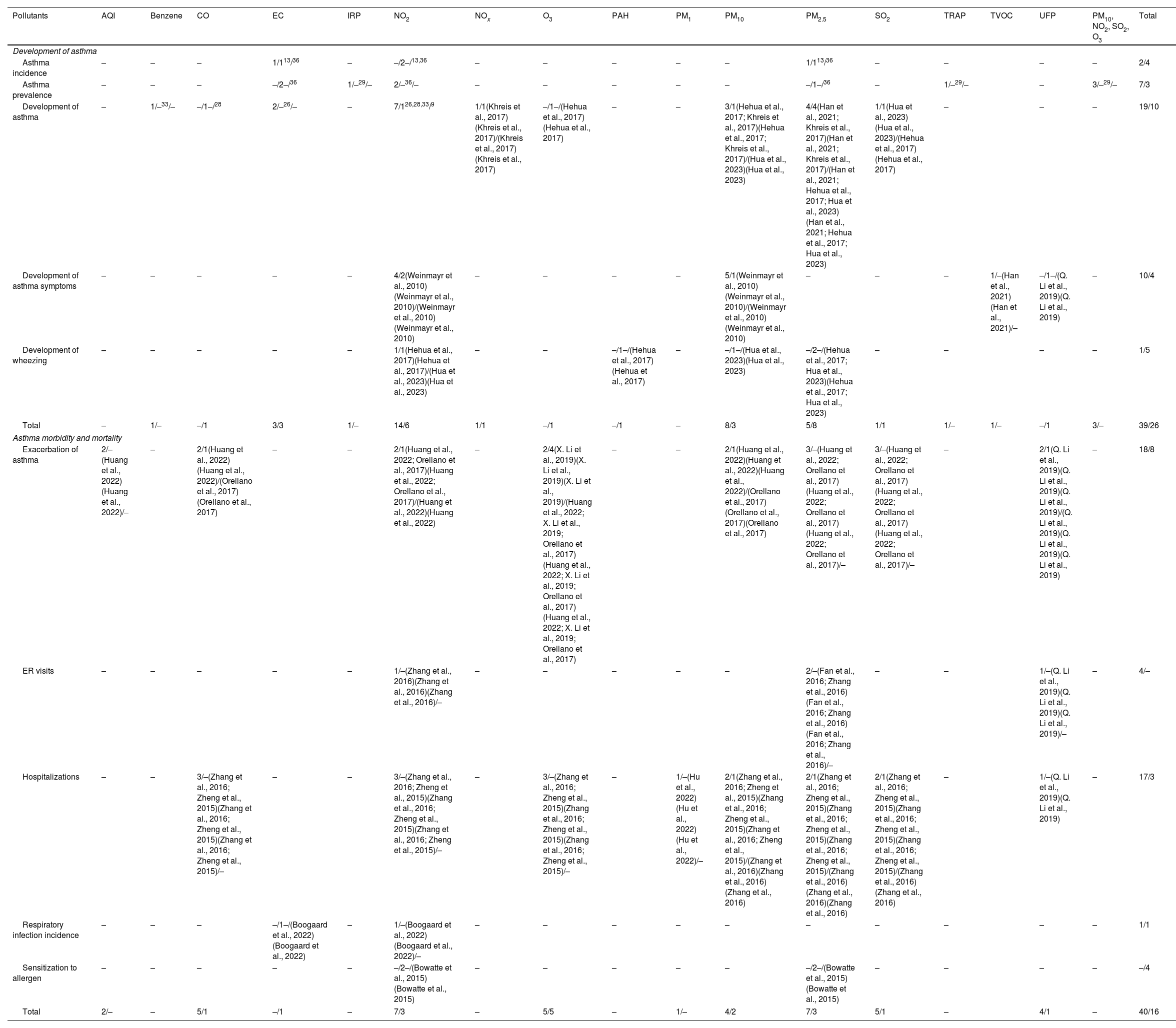

The association between air pollutants and asthma development in children was analyzed for each outcome and pollutant (Table 2). Statistically significant associations were identified between the asthma development in children and exposure to the following air pollutants: elemental carbon (EC), benzene, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter ≤10μm (PM10), particulate matter ≤2.5μm (PM2.5) and sulfur dioxide (SO2). In contrast, no associations were found between carbon monoxide (CO) and ozone (O3) and the asthma development. Additionally, significant associations were noted between asthma prevalence and industrialization-related pollution (IRP), NO2, traffic-related air pollution (TRAP), SO2, O3, and PM10.

Association between air pollutants and asthma development and exacerbation in children. Vote-counting of the number of statistically significant/not statistically significant items are shown for each outcome and pollutant.

| Pollutants | AQI | Benzene | CO | EC | IRP | NO2 | NOx | O3 | PAH | PM1 | PM10 | PM2.5 | SO2 | TRAP | TVOC | UFP | PM10, NO2, SO2, O3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development of asthma | ||||||||||||||||||

| Asthma incidence | – | – | – | 1/113/36 | – | –/2–/13,36 | – | – | – | – | – | 1/113/36 | – | – | – | – | 2/4 | |

| Asthma prevalence | – | – | – | –/2–/36 | 1/–29/– | 2/–36/– | – | – | – | – | – | –/1–/36 | – | 1/–29/– | – | 3/–29/– | 7/3 | |

| Development of asthma | – | 1/–33/– | –/1–/28 | 2/–26/– | – | 7/126,28,33/9 | 1/1(Khreis et al., 2017)(Khreis et al., 2017)/(Khreis et al., 2017)(Khreis et al., 2017) | –/1–/(Hehua et al., 2017)(Hehua et al., 2017) | – | – | 3/1(Hehua et al., 2017; Khreis et al., 2017)(Hehua et al., 2017; Khreis et al., 2017)/(Hua et al., 2023)(Hua et al., 2023) | 4/4(Han et al., 2021; Khreis et al., 2017)(Han et al., 2021; Khreis et al., 2017)/(Han et al., 2021; Hehua et al., 2017; Hua et al., 2023)(Han et al., 2021; Hehua et al., 2017; Hua et al., 2023) | 1/1(Hua et al., 2023)(Hua et al., 2023)/(Hehua et al., 2017)(Hehua et al., 2017) | – | – | – | 19/10 | |

| Development of asthma symptoms | – | – | – | – | – | 4/2(Weinmayr et al., 2010)(Weinmayr et al., 2010)/(Weinmayr et al., 2010)(Weinmayr et al., 2010) | – | – | – | – | 5/1(Weinmayr et al., 2010)(Weinmayr et al., 2010)/(Weinmayr et al., 2010)(Weinmayr et al., 2010) | – | – | – | 1/–(Han et al., 2021)(Han et al., 2021)/– | –/1–/(Q. Li et al., 2019)(Q. Li et al., 2019) | – | 10/4 |

| Development of wheezing | – | – | – | – | – | 1/1(Hehua et al., 2017)(Hehua et al., 2017)/(Hua et al., 2023)(Hua et al., 2023) | – | – | –/1–/(Hehua et al., 2017)(Hehua et al., 2017) | – | –/1–/(Hua et al., 2023)(Hua et al., 2023) | –/2–/(Hehua et al., 2017; Hua et al., 2023)(Hehua et al., 2017; Hua et al., 2023) | – | – | – | – | 1/5 | |

| Total | – | 1/– | –/1 | 3/3 | 1/– | 14/6 | 1/1 | –/1 | –/1 | – | 8/3 | 5/8 | 1/1 | 1/– | 1/– | –/1 | 3/– | 39/26 |

| Asthma morbidity and mortality | ||||||||||||||||||

| Exacerbation of asthma | 2/–(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)/– | – | 2/1(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)/(Orellano et al., 2017)(Orellano et al., 2017) | – | – | 2/1(Huang et al., 2022; Orellano et al., 2017)(Huang et al., 2022; Orellano et al., 2017)/(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022) | – | 2/4(X. Li et al., 2019)(X. Li et al., 2019)(X. Li et al., 2019)/(Huang et al., 2022; X. Li et al., 2019; Orellano et al., 2017)(Huang et al., 2022; X. Li et al., 2019; Orellano et al., 2017)(Huang et al., 2022; X. Li et al., 2019; Orellano et al., 2017) | – | – | 2/1(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)/(Orellano et al., 2017)(Orellano et al., 2017)(Orellano et al., 2017) | 3/–(Huang et al., 2022; Orellano et al., 2017)(Huang et al., 2022; Orellano et al., 2017)(Huang et al., 2022; Orellano et al., 2017)/– | 3/–(Huang et al., 2022; Orellano et al., 2017)(Huang et al., 2022; Orellano et al., 2017)(Huang et al., 2022; Orellano et al., 2017)/– | – | 2/1(Q. Li et al., 2019)(Q. Li et al., 2019)(Q. Li et al., 2019)/(Q. Li et al., 2019)(Q. Li et al., 2019)(Q. Li et al., 2019) | – | 18/8 | |

| ER visits | – | – | – | – | – | 1/–(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)/– | – | – | – | – | – | 2/–(Fan et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016)(Fan et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016)(Fan et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016)/– | – | – | 1/–(Q. Li et al., 2019)(Q. Li et al., 2019)(Q. Li et al., 2019)/– | – | 4/– | |

| Hospitalizations | – | – | 3/–(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)/– | – | – | 3/–(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)/– | – | 3/–(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)/– | – | 1/–(Hu et al., 2022)(Hu et al., 2022)(Hu et al., 2022)/– | 2/1(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | 2/1(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | 2/1(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | – | 1/–(Q. Li et al., 2019)(Q. Li et al., 2019) | – | 17/3 | |

| Respiratory infection incidence | – | – | – | –/1–/(Boogaard et al., 2022)(Boogaard et al., 2022) | – | 1/–(Boogaard et al., 2022)(Boogaard et al., 2022)/– | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1/1 | |

| Sensitization to allergen | – | – | – | – | – | –/2–/(Bowatte et al., 2015)(Bowatte et al., 2015) | – | – | – | – | – | –/2–/(Bowatte et al., 2015)(Bowatte et al., 2015) | – | – | – | – | –/4 | |

| Total | 2/– | – | 5/1 | –/1 | – | 7/3 | – | 5/5 | – | 1/– | 4/2 | 7/3 | 5/1 | – | 4/1 | – | 40/16 | |

AQI: air quality index; EC: elemental carbon; ER: emergency room; IRP: industrial-related pollution; PAH: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; PM: particulate matter; TRAP: traffic-related pollution; TVOC: total volatile organic compounds; UFP: ultrafine particles.

When considering asthma incidence, positive associations were found between EC and PM2.5, but no association was reported between NO2 and asthma incidence in children. Finally, associations were found between the development of asthma symptoms and NO2, PM10 and total volatile organic compounds (TVOC), but no association was found with ultrafine particles (UFP, particles <0.1μm). Specifically, NO2 exposure was positively associated to the development of wheezing in children, although no associations were found with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), PM10 and PM2.5 (Table 2).

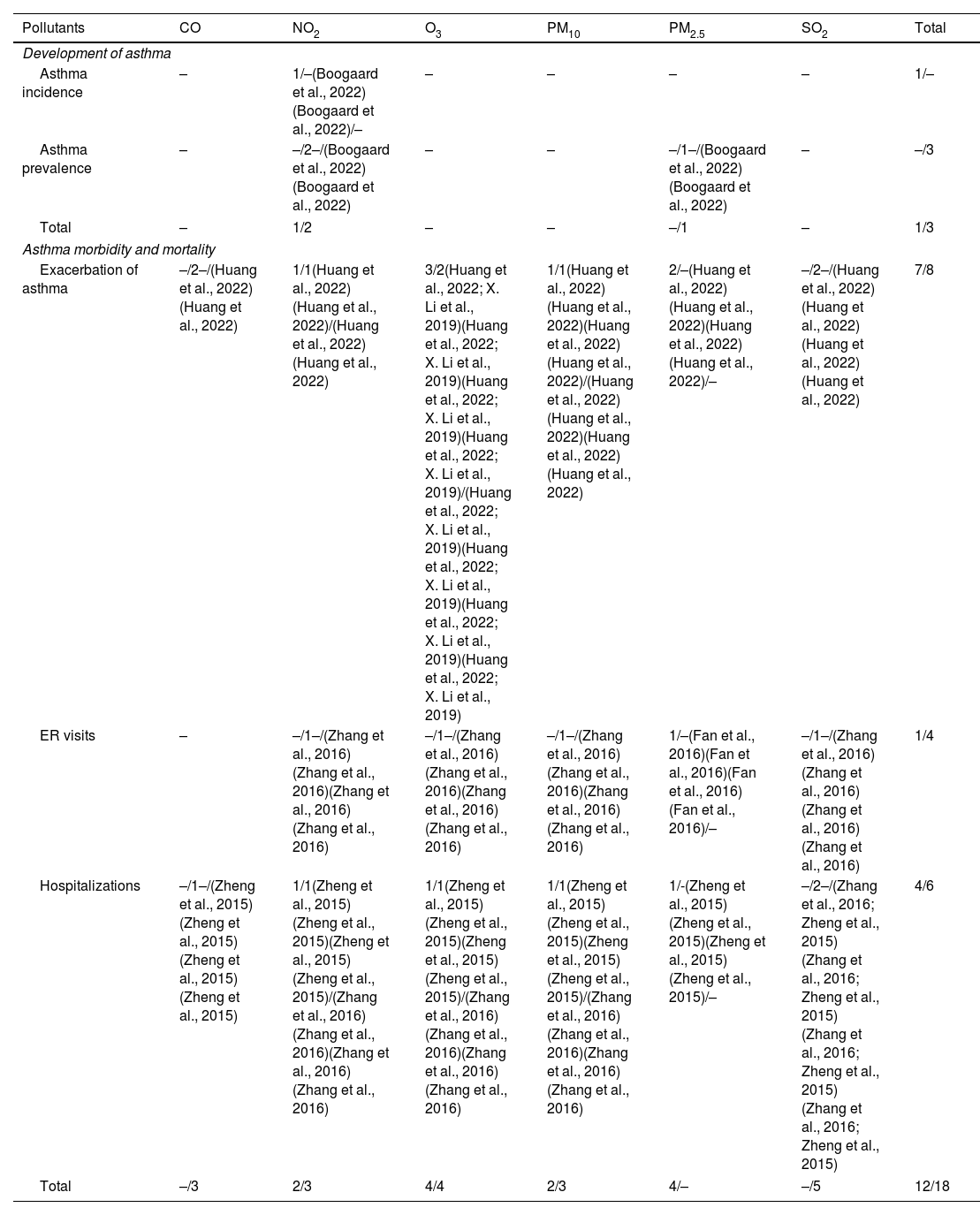

AdultsIn this population, only NO2 showed statistically significant association with asthma incidence in one systematic review. Moreover, no association was found between asthma prevalence and PM2.5 in one study (Table 3).

Association between air pollutants and asthma development and exacerbation in adults. Vote-counting of the number of statistically significant/not statistically significant items are shown for each outcome and pollutant.

| Pollutants | CO | NO2 | O3 | PM10 | PM2.5 | SO2 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development of asthma | |||||||

| Asthma incidence | – | 1/–(Boogaard et al., 2022)(Boogaard et al., 2022)/– | – | – | – | – | 1/– |

| Asthma prevalence | – | –/2–/(Boogaard et al., 2022)(Boogaard et al., 2022) | – | – | –/1–/(Boogaard et al., 2022)(Boogaard et al., 2022) | – | –/3 |

| Total | – | 1/2 | – | – | –/1 | – | 1/3 |

| Asthma morbidity and mortality | |||||||

| Exacerbation of asthma | –/2–/(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022) | 1/1(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)/(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022) | 3/2(Huang et al., 2022; X. Li et al., 2019)(Huang et al., 2022; X. Li et al., 2019)(Huang et al., 2022; X. Li et al., 2019)(Huang et al., 2022; X. Li et al., 2019)/(Huang et al., 2022; X. Li et al., 2019)(Huang et al., 2022; X. Li et al., 2019)(Huang et al., 2022; X. Li et al., 2019)(Huang et al., 2022; X. Li et al., 2019) | 1/1(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)/(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022) | 2/–(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)/– | –/2–/(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022)(Huang et al., 2022) | 7/8 |

| ER visits | – | –/1–/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | –/1–/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | –/1–/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | 1/–(Fan et al., 2016)(Fan et al., 2016)(Fan et al., 2016)(Fan et al., 2016)/– | –/1–/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | 1/4 |

| Hospitalizations | –/1–/(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015) | 1/1(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | 1/1(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | 1/1(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | 1/-(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)/– | –/2–/(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015) | 4/6 |

| Total | –/3 | 2/3 | 4/4 | 2/3 | 4/– | –/5 | 12/18 |

ER: emergency room; PM: particulate matter.

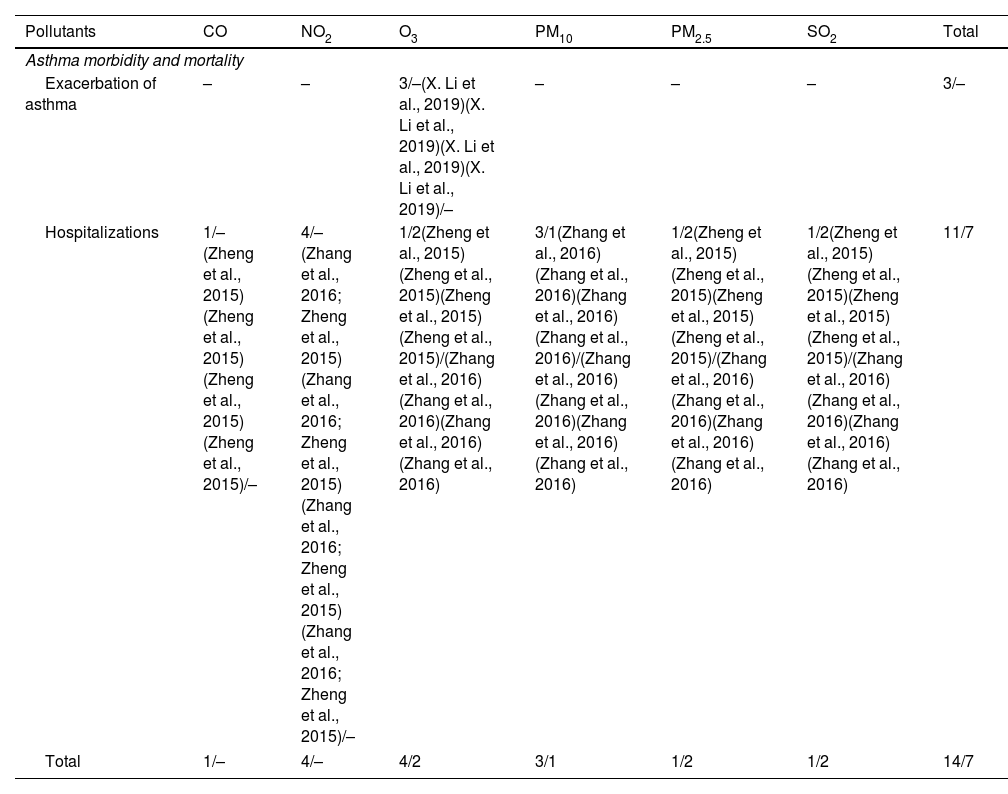

No information about air pollutants and asthma incidence or development in the elderly was reported in either study (Table 4).

Association between air pollutants and asthma development and exacerbation in the elderly. Vote-counting of the number of statistically significant/not statistically significant items are shown for each outcome and pollutant.

| Pollutants | CO | NO2 | O3 | PM10 | PM2.5 | SO2 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma morbidity and mortality | |||||||

| Exacerbation of asthma | – | – | 3/–(X. Li et al., 2019)(X. Li et al., 2019)(X. Li et al., 2019)(X. Li et al., 2019)/– | – | – | – | 3/– |

| Hospitalizations | 1/–(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)/– | 4/–(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)(Zhang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2015)/– | 1/2(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | 3/1(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | 1/2(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | 1/2(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)(Zheng et al., 2015)/(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016)(Zhang et al., 2016) | 11/7 |

| Total | 1/– | 4/– | 4/2 | 3/1 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 14/7 |

PM: particulate matter.

Subsequently, an analysis was conducted on the association between air pollutants and respiratory mortality across various age groups. However, none of the studies reviewed provided data on asthma-specific respiratory mortality across these age categories. Nonetheless, within the studies that did not specify age ranges, two review articles identified a significant association between exposure to certain pollutants – including elemental EC, NO2, and PM2.5 – and an increase in overall mortality (irrespective of the cause of death) (Supplementary Table 6).

Asthma morbidity and exacerbationChildrenWhen evaluating asthma morbidity in children, statistically significant associations between air quality index (AQI), CO, NO2, O3, PM10, PM2.5, SO2 and UFP and exacerbations of asthma were identified. Similarly, statistically significant associations between CO, NO2, O3, particulate matter ≤1μm (PM1), PM10, PM2.5, SO2 and UFP and hospitalizations. Additionally, statistically significant associations between NO2, PM2.5 and UFP exposure and emergency room (ER) visits were observed.

Finally, regarding respiratory infection incidence, a positive association with NO2 was found, but no association between EC and respiratory infection incidence was observed (Table 2).

AdultsRegarding asthma morbidity in adults, PM2.5 and O3 showed statistically significant associations with asthma exacerbation, while no associations were reported between SO2 and CO and exacerbations (Table 3).

Regarding ER visits, only PM2.5 showed a positive association among adults, while no association between ER visits and NO2, O3, PM10, and SO2 were observed. Finally, a statistically significant association between NO2, O3, PM2.5, PM10 and hospitalizations was identified (Table 3).

ElderlyThe only significant association between air pollutants and asthma exacerbation was found for O3 in one systematic review.31 Additionally, CO, NO2, O3, PM10, PM2.5 and SO2 showed statistically significant associations with hospitalization related to asthma exacerbations (Table 4).

Additionally, the results were also analyzed in the overall population. Statistically significant associations between ER visits and CO, NO2, O3, PM10, PM2.5 and SO2 were observed. In a similar way, it was reported statistically significant associations between asthma exacerbation and AQI, CO, NO2, O3, PM1, PM10, PM2.5. Finally, positive associations between asthma-related hospitalizations and AQI, CO, NO2, O3, PM10, PM2.5, SO2 were observed (Supplementary Table 6).

DiscussionThis narrative review synthesizes 379 data points from 20 studies published between April 2010 and November 2023. Each data point corresponds to a statistical measure representing the association between specific air pollutants and asthma-related outcomes. We conducted both overall and age-specific analyses to provide new insights into the association between outdoor air pollutants and the risk of developing asthma, as well as asthma-related morbidity and mortality.

This review strengthens the evidence for a positive association between exposure to pollutants – including elemental carbon (EC), benzene, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), coarse (PM10) and particulate matter ≤2.5μm (PM2.5), and sulfur dioxide (SO2) – and asthma development in children. Previous studies have also highlighted the negative impact of air pollution on asthma onset and clinical outcomes in both adults and children.6 According to the 2024 GINA Report,4 up to 13% of global childhood asthma incidence could be attributable to traffic-related air pollution (TRAP), which primarily consists of particulate matter (PM) known to have harmful effects on the respiratory system.4 In contrast, no significant associations were found between specific air pollutants and asthma development in adults and the elderly. Children are particularly vulnerable to air pollutants due to their underdeveloped respiratory and immune systems, higher ventilation rates, and reduced efficiency in filtering inhaled particles.26,37,38 Therefore, reducing exposure to pollutants during early life stages is crucial.

Our findings reinforce evidence for a positive association between air quality index (AQI) and components such as carbon monoxide (CO), NO2, ozone (O3), PM10, PM2.5, SO2, and ultrafine particles (UFP)with asthma exacerbations in children; PM2.5 and O3 with exacerbations in adults; and O3 with exacerbations in the elderly. Although the exact mechanisms by which air pollution aggravates asthma are not fully understood, pollutants are known to induce oxidative stress, sensitize individuals to aeroallergens, and promote airway inflammation, all of which can trigger asthma exacerbations.27,39 Specifically, exposure to PM, O3, NO2, and SO2 has been shown to cause airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness.10 These mechanisms may lead to increased exacerbations, worse clinical outcomes, and a higher healthcare burden. Our study further supports the association between PM2.5 and increased hospitalizations and ER visits across all age groups. Similarly, Anenberg et al. estimated that O3 and PM2.5 were responsible for 9–23 million and 5–10 million annual asthma-related ER visits globally in 2015, representing 8–20% and 4–9% of total visits, respectively.40

Although asthma was responsible for approximately 436,000 deaths in 2021, its relationship with mortality is complicated by the presence of comorbidities, making it difficult to establish direct causality. Due to the lack of studies specifically investigating the link between air pollution and asthma-related mortality, current data are insufficient to provide a clear explanation for asthma-attributed deaths. In this review, two studies demonstrated a significant association between EC, NO2, and PM2.5 and mortality in the general population.22,36 Another study reported a 2.8% increase in PM-related mortality for every 10μg/m3 rise in PM2.5 exposure.41 Naess et al. found that chronic exposure to NO2, PM10, and PM2.5 was consistently linked to an increased risk of mortality from all causes, with the effects being more pronounced at NO2 levels above 40μg/m3 in younger populations and in the 20–60μg/m3 range for older individuals.42 Although asthma is most prevalent in children, the highest asthma-related mortality rates are seen in the elderly.1

Notably, between 1990 and 2015, asthma-related mortality decreased by 58.5%, though reductions in years lived with disability (YLDs) were far smaller.1 This suggests that interventions have reduced asthma's fatality, but not its incidence, making it more of a chronic condition. Asthma can be effectively managed with preventive treatment and rescue medications during flare-ups. In low- and middle-income countries, where access to healthcare and treatments may be limited, asthma-related mortality rates remain high, underscoring the impact of sociodemographic factors on asthma mortality.1

Reducing exposure to outdoor pollutants is critical for improving asthma incidence and morbidity. This requires policy actions and a strong commitment to reduction of emissions. Emissions from human activities account for approximately 37% of the impact of O3-related respiratory effects and 73% of the contribution to PM2.5-related respiratory effects, including exacerbation of asthma symptoms and increased asthma-related morbidity.40 Therefore, reducing outdoor pollution should be a priority for minimizing asthma risk factors and associated burdens. The improvements in air quality observed during COVID-19 lockdowns, which coincided with a significant reduction in acute asthma exacerbations, further support this need, although the effect may have been temporary.43

Moreover, since daily exposure to multiple pollutants has been associated with increased use of asthma rescue medication, reliable air pollution forecasts could serve as valuable predictors of exacerbations.44

Future studiesThe association between air pollution and asthma has been extensively studied, but its significance compared to other causes of asthma exacerbation, such as viral infections, requires further investigation. Additionally, a more accurate understanding of PM composition could help clarify its effects on the body and, consequently, its role in asthma development and exacerbation. Therefore, continued research in this area is essential. Lastly, studies examining the use of digital systems to monitor the impact of specific pollutants on asthma outcomes are still limited. These systems could prove valuable not only in predicting a patient's need for additional resources, such as medication, but also in anticipating the demands on healthcare facilities.

Strengths and limitationsThis study has several strengths, such as the inclusion of data from meta-analyses and derived from a systematic literature search. Meta-analyses provide more robust data than other sources of information implying higher quality data. Furthermore, two independent reviewers examined the eligible studies based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data extraction was performed using a standardized form previously and ad hoc defined for this project.

A notable limitation of this study lies in the heterogeneity of the systematic reviews included. Data included was heterogeneous and proceeded from different regions all over the world. The geographical characteristics, weather, climate and industrialization of each region also affect air quality and its potential impact on the results cannot be ruled out. Additionally, while the study encompasses a comprehensive set of literature, it acknowledges the absence of data from densely populated regions such as India and Africa, which limits the applicability of the findings to these areas.

Furthermore, it is important to highlight that potential overlaps between studies included in different meta-analyses were not excluded in this review, which could lead to some degree of overestimation in the results. However, based on the nature of the studies reviewed, the magnitude of this potential overestimation is not anticipated to be substantial.

Lastly, the systematic reviews analyzed may not have accounted for all potential confounding factors that may have had an influence on asthma incidence and exacerbation outcomes, such as socioeconomic factors, race or occupational risks.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, a significant association between air pollutants and asthma development was observed in children but not in adults. Additionally, air pollutants were associated with increased morbidity (such as exacerbations and hospitalizations) in both children and adults, and with increased mortality among children and the elderly. These findings underscore the serious health impacts of air pollution and emphasize the need for policymakers to prioritize environmental policies aimed at preventing asthma development and mitigating related health outcomes.

Further cumulative meta-analyses are needed to clarify the specific associations between air pollutants and distinct asthma-related outcomes to enable more reliable conclusions.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processNo generative artificial intelligence (AI) or AI-assisted technologies were used in the writing, editing, or creation of this manuscript. All content was produced by the authors.

FundingThis review was sponsored and funded by Chiesi España S.A. which covered the design of the strategy for the review, its implementation, the analysis of the results and the editorial support for medical writing.

DE is a researcher supported by the Rio Hortega program from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CM23/00174).

Authors’ contributionsAll authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work as well as the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to the drafting of the work and undertook critical review for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

DE has received fees as a speaker from AstraZeneca. VP in the last three years received honoraria for speaking at sponsored meetings from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, Gebro, GSK, Luminova-Medwell and Sanofi, received help assistance to meeting travel from AstraZeneca and Chiesi and acted as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GSK and Menarini.

SQ has been on advisory boards for and has received speaker's honoraria from Allergy Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Gebro, Novartis and Sanofi.

JAT in the last three years has received fees as speaker, scientific advisor or participant of clinical studies of: AstraZeneca, Bial, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Teva.

XM has received fees as a speaker, scientific advisor or participant of clinical studies of (in alphabetical order): AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Faes, Gebro, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Mundifarma, Novartis, Sanofi, Teva.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Carla Arús, Inmaculada Molina, and Gloria González from Adelphi Targis for their invaluable support in the development of this literature review, as well as for providing editorial and medical writing assistance in preparing this manuscript. The authors would like to thank Alba Gómez, PhD, for medical writing assistance.