Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, degenerative disease of the central nervous system with a complex and uncertain etiology. Although therapeutic advances have improved disease control, both prognosis and treatment monitoring continue to be challenging. Serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL), a marker of neuroaxonal damage, is emerging as a useful biomarker to improve disease monitoring.

DevelopmentThis article addresses the interpretation of sNfL levels in patients with MS and their correlation with inflammatory activity and disease progression. We also discuss the role of sNfL in detecting subclinical axonal damage, which may allow for adjustments in therapeutic decision-making at different stages of the disease.

ConclusionsIncorporating sNfL measurement into the routine practice of neurologists, as a complement to clinical evaluation and magnetic resonance imaging, represents an advance in the follow-up of patients with MS. In specific scenarios, as detailed in the article, it can help optimise therapeutic decision-making and prevent further neuroaxonal damage. While the current evidence is already strong, further validation of its application is necessary. The widespread use of this biomarker by neurologists is a key step in generating that evidence.

La esclerosis múltiple (EM) es una enfermedad inflamatoria y degenerativa del sistema nervioso central con una etiología compleja e incierta. Aunque los avances terapéuticos han mejorado el control de la enfermedad, el pronóstico y la monitorización del tratamiento continúan siendo un desafío. La cadena ligera de los neurofilamentos en suero (sNfL), reflejo de daño neuroaxonal, emerge como biomarcador útil dotando al neurólogo de una herramienta para mejorar dicha monitorización.

DesarrolloEste trabajo aborda la interpretación de los niveles de sNfL en pacientes con EM, y su correlación con la actividad inflamatoria y la progresión de la enfermedad. Asimismo, se discute el papel de sNfL para detectar daño axonal subclínico que permita ajustar la toma de decisiones terapéuticas en diferentes momentos de la enfermedad.

ConclusionesLa incorporación de la determinación de sNfL en la práctica habitual del neurólogo, como complemento a la evaluación clínica y de imagen mediante resonancia magnética, supone un avance en el seguimiento de los pacientes con EM. En escenarios definidos como los detallados en el artículo, puede ayudar a optimizar las decisiones terapéuticas y prevenir un mayor daño neuroaxonal. Aunque la evidencia actual ya es sólida, es necesario seguir validando su aplicación. La generalización de su uso por parte los neurólogos es clave para la generación de esa evidencia.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, degenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS), characterised by complex aetiology, heterogeneous clinical presentation, and uncertain progression. Recent advances in MS treatment have enabled greater control of the disease in terms of reducing the number of relapses and active and inactive CNS lesion load detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), although the effect on the progression of disability is more modest.1 Treatment selection is a complex process and must be considered on an individual basis, partly due to the lack of direct comparisons between drugs, but also given the importance of considering each drug's safety profile, tolerability, administration route, and dosing, in addition to clinical experience, availability, treatment cost, and patient preferences. Furthermore, many of the parameters used for comparison are highly subjective.2

To date, therapeutic decision-making and the monitoring and follow-up of disease progression have been based on clinical and MRI data, as well as the presence or absence of certain prognostic factors. The prognostic factors currently used to inform therapeutic decision-making do not predict neurological damage caused by the disease, as the majority are non-modifiable factors and can only be evaluated retrospectively. Furthermore, the information offered by these data is incomplete; therefore, MS progression is uncertain as a result of the lack of prognostic markers that offer good sensitivity and, ideally, reflect subclinical activity and predict damage to the target organ, even before this damage has occurred. Serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL) has emerged in recent years as a good blood marker of axonal damage in such CNS diseases as MS. Thus, while determination of this marker is only available at a small number of Spanish hospitals, its generalisation may be highly valuable in clinical practice.

With a view to gathering all the available evidence on the usefulness of sNfL in MS, we conducted a non-systematic literature search on PubMed®, combining the search terms “neurofilament, neurofilaments, NfL” and “multiple sclerosis, MS.” All articles published in English or Spanish between 2013 and 2024 were consulted, after screening for relevance for this consensus statement.

This study presents the position of the Spanish Society of Neurology's Study Group on Multiple Sclerosis and Related Neuroimmune Diseases (GEEMENIR) on the need to integrate sNfL determination into MS care. Given its value in prognosis and in the monitoring of disease progression and treatment response, the technique may improve the quality and efficiency of care provided to patients with MS.

Biomarkers in multiple sclerosisConsiderable research efforts have been focused on the identification of a highly sensitive, reproducible, objective, non-invasive, and easily interpreted biomarker to overcome the numerous outstanding challenges in predicting prognosis and treatment response in patients with MS.3 To date, the main biomarker used in MS prognosis and follow-up has been MRI. Lesion number and location are used as predictive factors of conversion to MS and enable the identification of patients with highly active forms of the disease.4,5 Furthermore, more advanced MRI techniques are able to identify axonal damage (fundamentally represented by atrophy6) and other chronic inflammatory and neurodegenerative processes.7 Such other imaging techniques as optical coherence tomography may provide complementary data to inform prognosis and therapeutic decision-making, although there is still a need to confirm its reproducibility and relevance in clinical practice and to facilitate neurologists’ access to this technique.8,9

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis has also played a fundamental role in understanding the pathophysiology and prognosis of the disease. Intrathecal B-cell activity, determined according to the presence of oligoclonal bands (OCB) in the CSF or using the Kappa index, may help to confirm the diagnosis of MS in clinically isolated syndrome (CIS).3,10–12 In addition to this, the presence of lipid-specific IgM OCBs in the CSF is an established prognostic factor for disease activity in MS.10 However, the need for repeated extraction of CSF limits its potential for monitoring treatment outcomes.13

Recent studies report alterations in various cytokines, chemokines, and other inflammatory mediators in the CSF and in the blood of patients with MS.8 Many of the biomarkers identified present limitations related to sample extraction (in the case of CSF), the reproducibility of the technique, the difficulty of determination, or limited prognostic relevance.14 Therefore, identifying accessible, reproducible biomarkers is a priority. In this regard, serum determinations are preferred over other tests due to the simplicity of obtaining samples. Serum NfL has been shown to be a reliable marker of axonal damage,15 with numerous studies demonstrating its clinical relevance as a predictor of disease progression and treatment response.16,17 Thanks to improvements in serum detection techniques, it has been possible to demonstrate the existence of a close correlation between values in the CSF and in the serum, which has improved the availability of the technique in clinical practice.18

Serum neurofilament light chainNeurofilaments are specific neuronal cytoskeleton proteins that are present in both the CNS and the peripheral nervous system.19 Their main function is to provide structural stability and to maintain homeostasis and axonal polarisation. With the loss of integrity of the neuronal cell membrane in the CNS, neurofilaments are released into the extracellular space and eventually into the CSF and the bloodstream.20 These proteins are highly specific markers of tissue damage, and reflect MS pathophysiology, as they are specifically linked to the target organ.

Elevated sNfL values indicate neuroaxonal damage. This parameter is considered a valid clinical marker for monitoring tissue damage and therefore the response to MS treatment.21 In addition to the advantage of being measurable in the serum, NfL is stable at room temperature and in frozen blood samples (and resistant to freeze–thaw cycles); therefore, it enables us to evaluate the degree of neuroaxonal damage in a standard patient consultation. Furthermore, the samples obtained may be stored in a serum bank for future analysis.16,22

Technological advances in neurofilament light chain measurementThe introduction of new technologies has enabled the detection of NfL in the serum at low concentrations through the use of third- and fourth-generation assays.23 Single-molecule array (SIMOA) is currently the most widely used technique for measuring sNfL in the majority of published studies, facilitating the standardisation of patient monitoring and enabling the development of multicentre studies.24 Furthermore, SIMOA reliably quantifies sNfL levels across the entire range of concentrations observed in both physiological and pathological conditions.25

Considerable efforts are being made to use other techniques (Simple Plex Ella, Fujirebio, and ADVIA Centaur, among others) to replicate the results obtained with SIMOA. These technologies are currently being validated, and their correlation with the data obtained using the reference technique must be established. The results obtained with one method cannot be directly extrapolated to others until we verify their sensitivity, detection thresholds, and correlation with SIMOA.25

In well-controlled MS, sNfL values are low, which may limit the potential use of this marker in the monitoring of treatment efficacy if the techniques employed are less sensitive or present a floor effect. This limitation may not occur in other diseases, in which sNfL levels are higher.26

Interpretation of serum neurofilament light chain levelsTwo approaches are currently applied in interpreting NfL levels: cut-off scores and Z-scores, each of which presents its own advantages and limitations. The use of absolute sNfL values is simpler and more specific, but presents lower sensitivity,27 whereas the Z-score can minimise the influence of patient body mass index and age in interpretation.28

Generally, sNfL values (measured with SIMOA) greater than 10pg/mL, or Z-scores greater than 1.5, are considered to be pathological; in the case of MS, such values may indicate suboptimal control of the disease.21,29 It is crucial to consider the moment at which sNfL determination is performed: very early measurement during a relapse may not reflect axonal damage, as sNfL values tend to peak an average of 5.5 weeks later, with a gradual decrease thereafter.30

In patients with significant comorbidities, such as kidney failure, poorly controlled diabetes, or alcohol abuse, results must be interpreted with caution as NfL levels may be altered.31,32 Therefore, it is essential to consider individual values within the clinical context of each patient.

It should be noted that elevated NfL is not specific to MS. Elevated serum or CSF NfL may also be detected in other diseases that cause neuroaxonal damage, including Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, as well as such CNS infections as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML)25,33,34; this constitutes a limitation for the diagnostic specificity of the technique, but not for the follow-up of patients with MS or for ruling out infectious complications associated with treatment.

Relationship between serum neurofilament light chain values and disease controlThe minimal invasiveness of sNfL determination represents a significant advance that may lead to its generalised use in patients with MS. In this section, we present a critical review of the current role of sNfL in responding to key clinical issues, such as selection of the initial treatment and detection of subclinical disease activity, alongside MRI, and the need to escalate or switch therapies in patients presenting suboptimal response.

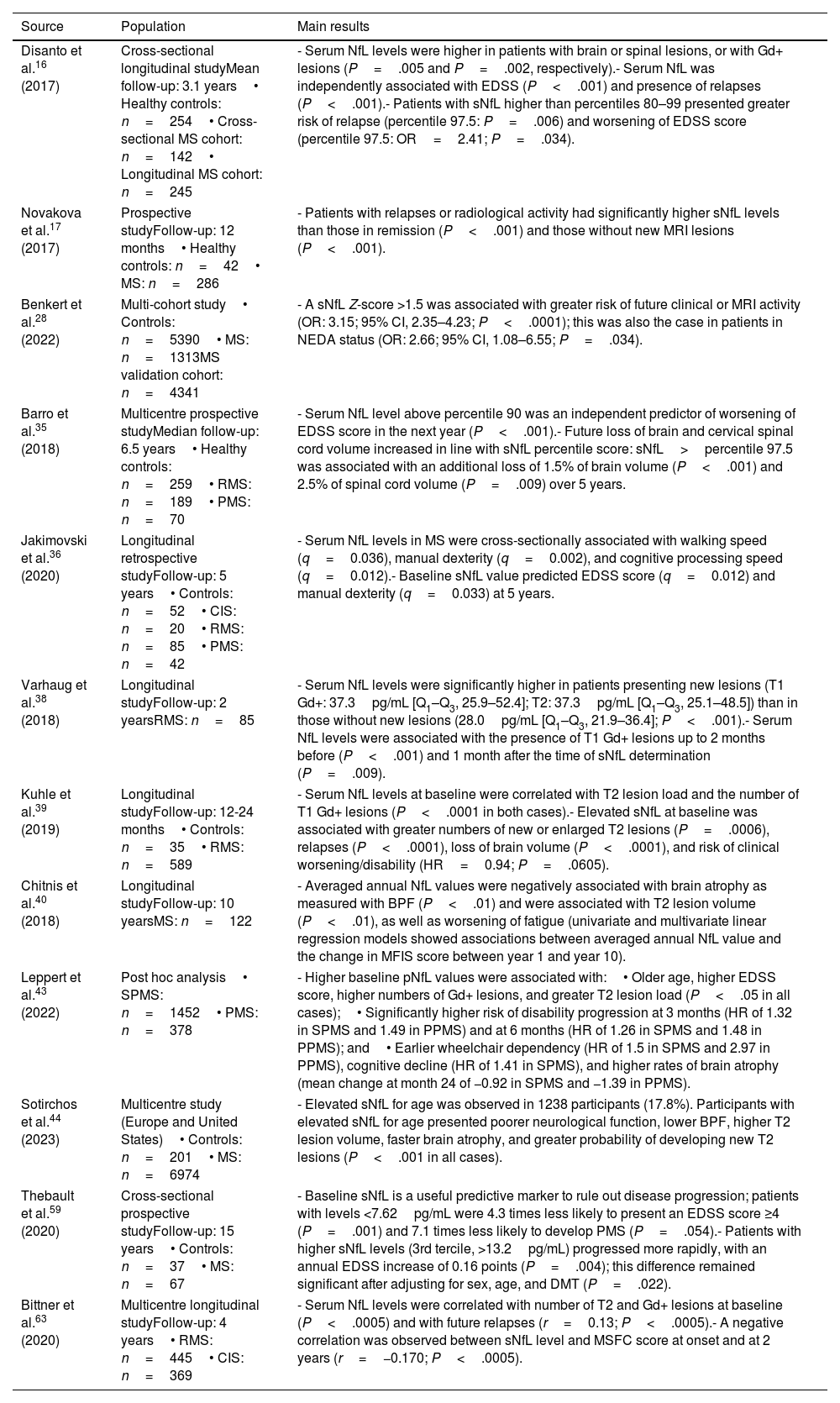

The correlation between sNfL and inflammatory activity and disease progressionCurrent evidence confirms that sNfL plays a key role as a biomarker of present and future disease activity. As shown in Table 1, as NfL are specific neuronal proteins, elevated sNfL levels indicate that inflammatory lesions are associated with neuroaxonal damage.21 In fact, the inclusion of sNfL level as an additional parameter in the 2017 McDonald criteria increases their sensitivity and specificity for identifying patients with CIS who will progress to relapsing MS (RMS).21

The most relevant evidence on the correlation between serum neurofilament light chain level (measured with SIMOA) and clinical and imaging parameters.

| Source | Population | Main results |

|---|---|---|

| Disanto et al.16 (2017) | Cross-sectional longitudinal studyMean follow-up: 3.1 years• Healthy controls: n=254• Cross-sectional MS cohort: n=142• Longitudinal MS cohort: n=245 | - Serum NfL levels were higher in patients with brain or spinal lesions, or with Gd+ lesions (P=.005 and P=.002, respectively).- Serum NfL was independently associated with EDSS (P<.001) and presence of relapses (P<.001).- Patients with sNfL higher than percentiles 80–99 presented greater risk of relapse (percentile 97.5: P=.006) and worsening of EDSS score (percentile 97.5: OR=2.41; P=.034). |

| Novakova et al.17 (2017) | Prospective studyFollow-up: 12 months• Healthy controls: n=42• MS: n=286 | - Patients with relapses or radiological activity had significantly higher sNfL levels than those in remission (P<.001) and those without new MRI lesions (P<.001). |

| Benkert et al.28 (2022) | Multi-cohort study• Controls: n=5390• MS: n=1313MS validation cohort: n=4341 | - A sNfL Z-score >1.5 was associated with greater risk of future clinical or MRI activity (OR: 3.15; 95% CI, 2.35–4.23; P<.0001); this was also the case in patients in NEDA status (OR: 2.66; 95% CI, 1.08–6.55; P=.034). |

| Barro et al.35 (2018) | Multicentre prospective studyMedian follow-up: 6.5 years• Healthy controls: n=259• RMS: n=189• PMS: n=70 | - Serum NfL level above percentile 90 was an independent predictor of worsening of EDSS score in the next year (P<.001).- Future loss of brain and cervical spinal cord volume increased in line with sNfL percentile score: sNfL>percentile 97.5 was associated with an additional loss of 1.5% of brain volume (P<.001) and 2.5% of spinal cord volume (P=.009) over 5 years. |

| Jakimovski et al.36 (2020) | Longitudinal retrospective studyFollow-up: 5 years• Controls: n=52• CIS: n=20• RMS: n=85• PMS: n=42 | - Serum NfL levels in MS were cross-sectionally associated with walking speed (q=0.036), manual dexterity (q=0.002), and cognitive processing speed (q=0.012).- Baseline sNfL value predicted EDSS score (q=0.012) and manual dexterity (q=0.033) at 5 years. |

| Varhaug et al.38 (2018) | Longitudinal studyFollow-up: 2 yearsRMS: n=85 | - Serum NfL levels were significantly higher in patients presenting new lesions (T1 Gd+: 37.3pg/mL [Q1–Q3, 25.9–52.4]; T2: 37.3pg/mL [Q1–Q3, 25.1–48.5]) than in those without new lesions (28.0pg/mL [Q1–Q3, 21.9–36.4]; P<.001).- Serum NfL levels were associated with the presence of T1 Gd+ lesions up to 2 months before (P<.001) and 1 month after the time of sNfL determination (P=.009). |

| Kuhle et al.39 (2019) | Longitudinal studyFollow-up: 12-24 months• Controls: n=35• RMS: n=589 | - Serum NfL levels at baseline were correlated with T2 lesion load and the number of T1 Gd+ lesions (P<.0001 in both cases).- Elevated sNfL at baseline was associated with greater numbers of new or enlarged T2 lesions (P=.0006), relapses (P<.0001), loss of brain volume (P<.0001), and risk of clinical worsening/disability (HR=0.94; P=.0605). |

| Chitnis et al.40 (2018) | Longitudinal studyFollow-up: 10 yearsMS: n=122 | - Averaged annual NfL values were negatively associated with brain atrophy as measured with BPF (P<.01) and were associated with T2 lesion volume (P<.01), as well as worsening of fatigue (univariate and multivariate linear regression models showed associations between averaged annual NfL value and the change in MFIS score between year 1 and year 10). |

| Leppert et al.43 (2022) | Post hoc analysis• SPMS: n=1452• PMS: n=378 | - Higher baseline pNfL values were associated with:• Older age, higher EDSS score, higher numbers of Gd+ lesions, and greater T2 lesion load (P<.05 in all cases);• Significantly higher risk of disability progression at 3 months (HR of 1.32 in SPMS and 1.49 in PPMS) and at 6 months (HR of 1.26 in SPMS and 1.48 in PPMS); and• Earlier wheelchair dependency (HR of 1.5 in SPMS and 2.97 in PPMS), cognitive decline (HR of 1.41 in SPMS), and higher rates of brain atrophy (mean change at month 24 of −0.92 in SPMS and −1.39 in PPMS). |

| Sotirchos et al.44 (2023) | Multicentre study (Europe and United States)• Controls: n=201• MS: n=6974 | - Elevated sNfL for age was observed in 1238 participants (17.8%). Participants with elevated sNfL for age presented poorer neurological function, lower BPF, higher T2 lesion volume, faster brain atrophy, and greater probability of developing new T2 lesions (P<.001 in all cases). |

| Thebault et al.59 (2020) | Cross-sectional prospective studyFollow-up: 15 years• Controls: n=37• MS: n=67 | - Baseline sNfL is a useful predictive marker to rule out disease progression; patients with levels <7.62pg/mL were 4.3 times less likely to present an EDSS score ≥4 (P=.001) and 7.1 times less likely to develop PMS (P=.054).- Patients with higher sNfL levels (3rd tercile, >13.2pg/mL) progressed more rapidly, with an annual EDSS increase of 0.16 points (P=.004); this difference remained significant after adjusting for sex, age, and DMT (P=.022). |

| Bittner et al.63 (2020) | Multicentre longitudinal studyFollow-up: 4 years• RMS: n=445• CIS: n=369 | - Serum NfL levels were correlated with number of T2 and Gd+ lesions at baseline (P<.0005) and with future relapses (r=0.13; P<.0005).- A negative correlation was observed between sNfL level and MSFC score at onset and at 2 years (r=−0.170; P<.0005). |

BPF: brain parenchymal fraction; CI: confidence interval; CIS: clinically isolated syndrome; DMT: disease-modifying therapy; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; Gd+: gadolinium-enhancing; HR: hazard ratio; MFIS: Modified Fatigue Impact Scale; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MS: multiple sclerosis; MSFC: Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite; NEDA: no evidence of disease activity; OR: odds ratio; PMS: progressive multiple sclerosis; pNfL: plasma neurofilament light chain; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; Q1–Q3: quartiles 1 and 3; RMS: relapsing multiple sclerosis; sNfL: serum neurofilament light chain; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Longitudinal studies, such as that performed by Barro et al.,35 including 6.5 years of follow-up, report that the risk of worsening of disability (as measured with the Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]) gradually increases in line with sNfL percentile level. Similarly, Jakimovski et al.36 reported that elevated sNfL is associated with greater risk of deterioration in physical and cognitive performance and of progression from RMS to progressive MS (PMS). Abdelhak et al.37 also showed that an increase in sNfL level predicts disability accumulation. Furthermore, sNfL has been validated as a reliable measure of disease activity, complementing clinical assessments and MRI, and is particularly useful for detecting subclinical disease activity in apparently stable patients or those in NEDA-3 (no evidence of disease activity) status.28,38

Serum NfL level has also been correlated with brain and spine atrophy, predicting not only clinical and MRI changes, but also overall disease impact.35,38,39 Several studies have shown sNfL to be a reliable biomarker of relapses and gadolinium-enhancing (Gd+) lesions: levels peak during a 3-month window around the time of the lesion, and correlate with the number of new or enlarging T2 lesions, consolidating the role or sNfL as a marker of inflammation.40,41,42

With regard to progressive forms, the post hoc analysis by Leppert et al.,43 based on two randomised controlled trials with a total of 4185 NfL determinations from plasma samples from patients with PMS, confirmed that baseline sNfL levels were associated with future progression of disability, cognitive impairment, and loss of brain volume, even in the absence of signs of acute inflammation.

Despite these advances, validation with real life data is crucial to the implementation of sNfL measurement in clinical practice. A recent study by Sotirchos et al.,44 including over 7000 patients, further supports the biological value of sNfL as a marker, associating it with clinical and radiological variables indicative of greater clinical disability, inflammatory activity, and brain atrophy. These findings suggest that measuring sNfL levels during the first year of disease progression may help identify optimal candidates for high- or very high-efficacy disease-modifying treatments (DMT). A delay in the selection of an appropriate treatment may result in greater functional deterioration and missed opportunities.45,46 For instance, patients with elevated sNfL at baseline have been shown to be less likely to respond to moderate-efficacy treatments, which is predictive of suboptimal response and the need to begin or escalate to higher-efficacy treatments.45,47

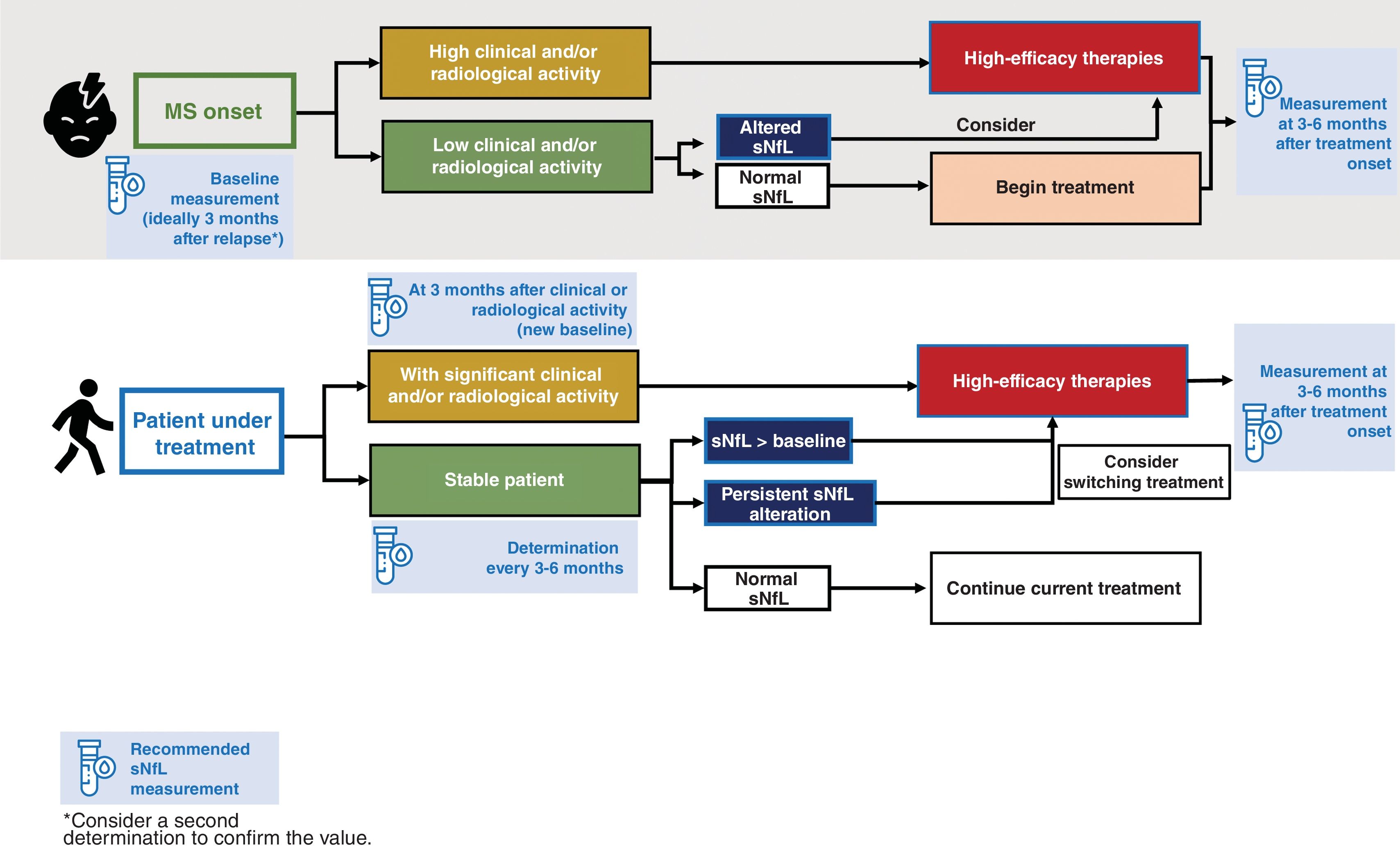

Monitoring of treatment response through serum neurofilament light chain determinationCurrently, around 20 DMTs have been registered to treat MS. Various clinical studies have demonstrated that sNfL level is treatment-sensitive, further supporting its value as a biomarker of disease activity. The correlation between administration of DMT and lower sNfL levels48–50 offers the opportunity for early optimisation of treatment (Fig. 1).

During the follow-up of patients with MS, it is essential for neurologists to periodically review the treatment strategy to identify early failures and make adjustments to treatment.51 Periodic sNfL measurement after introduction of a treatment enables us to predict clinical response from an early stage. For example, treatment with monoclonal antibodies (alemtuzumab and natalizumab), and to a lesser extent oral drugs (fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate, and teriflunomide), usually leads to normalisation of sNfL levels, which may persist over time.52 In general, monoclonal antibodies seem to reduce sNfL levels faster and more intensely than oral therapies, although both treatment strategies are more efficacious than platform therapies such as interferon beta (IFN-β-1a),8 which are reported to behave more irregularly, with the therapeutic effect even being lost in some cases.28,38,39

Serial sNfL measurements may be predictive of treatment response; in patients presenting an inadequate response, this enables earlier decision-making and optimisation of the second therapeutic window. Serum NfL determination helps to evaluate the efficacy of a DMT, with levels being correlated with treatment response, and supports treatment switches when necessary, as serial measurements can be taken (at baseline and at 3 and 6 months) with a minimal burden for the patient or the healthcare system.

The capacity of sNfL to measure ongoing neuroaxonal loss in real time enables us to predict the development of established inflammatory lesions before clinical changes become detectable or disability progression occurs. For this reason, beyond its clinical application, the technique is being used in clinical trials to assess treatment response.53 As a whole, patients with elevated sNfL may be eligible for higher-efficacy treatments to prevent greater neuroaxonal damage (Fig. 1).

Serum NfL determination is also useful for monitoring treatment safety. Specifically, it allows for identification of patients with RMS who may be developing PML during treatment with natalizumab, facilitating early detection of this severe complication (level of evidence I).54–56

Serum neurofilament light chain determination in the prognosis of multiple sclerosisNumerous studies have supported the implementation of sNfL determination alongside clinical and imaging markers to improve sensitivity in predicting MS prognosis and progression. The combination of serum and imaging markers increases our capacity to predict disability progression.28,57 Although baseline sNfL measurement in isolation already provides considerable prognostic value, longitudinal measurements offer greater long-term predictive power.58,59 This situation has also been confirmed in patients with PMS, in which sNfL continues to be a valuable prognostic marker of future disability progression.60 Furthermore, numerous studies have suggested that sNfL can predict progression independent of relapse activity (PIRA), one of the main mechanisms of disability accumulation in MS,29,61 although its value in PIRA in the absence of inflammation remains unclear.

This section on the prognostic value of the biomarker would be incomplete without mentioning patients with radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS), up to 50% of whom progress to MS within 10 years.62 The presence of elevated sNfL levels in these patients is suggestive of damage to the target organ; this, in addition to predicting clinically definite MS,63,64 may be considered as a first manifestation of MS, supporting the potential need for early onset of immunomodulatory treatment.

Perspectives and recommendations for the use of serum neurofilament light chain determination in multiple sclerosisThis consensus statement summarises the available evidence on the use of sNfL in MS, underscoring its value as a biomarker in characterising disease severity and in rapid decision-making. Its high sensitivity in detecting subclinical neuroaxonal damage satisfies a crucial need in the current monitoring of MS.

Based on the studies reviewed and the recommendations of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers,29 we suggest that sNfL be measured in the following key situations:

- •

at disease onset;

- •

in the baseline assessment, and again at 3 or 6 months after starting or switching treatment;

- •

in patients in NEDA-3 status, every 3–6 months;

- •

3 months after observation of clinical or radiological activity (to establish a new baseline value);

- •

in patients in whom disease activity must be confirmed, for instance in cases of RIS, suspected pseudorelapse, or progressive MS.

It is likely that with time, the use of sNfL determination will expand to other situations not covered by these recommendations, such as during treatment suspension or de-escalation.

ConclusionsSerum neurofilament light chain is the first blood biomarker that offers simple, objective, sensitive prediction of disease activity and treatment response in MS. In the clinical context, sNfL offers significant advantages: it is inexpensive, enables real-time monitoring of neuroaxonal damage, requires few resources, and favours repeated non-invasive measurements. These attributes improve the monitoring of MS, optimise therapeutic decision-making, and have a positive impact on prognosis. The dissemination of this information and the availability of testing for this biomarker among neurologists is essential to its implementation in clinical practice, thereby promoting evidence-based medicine and avoiding the therapeutic inertia that can compromise patient outcomes.

FundingEditorial assistance from Medical Statistics Consulting, S. L. was funded by the Spanish Society of Neurology.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors thank Miriam Ejarque, PhD, and Javier Arranz, PhD, of Medical Statistics Consulting, S. L., for their assistance in compiling the authors’ contributions and in the drafting and editing of the manuscript in accordance with the Good Publication Practice guidelines.